Fairytale Motifs – Gothic Readings – The Internal Tribunal

KAFKA: THE TRIAL – ANALYSIS – PART 1

Patrick Bridgwater

From Patrick Bridgwater, Kafka, Gothic and Fairytale (Amsterdam-New York: Editions Rodopi, 2003) pp. 123-134.

I have abbreviated the text very slightly to promote readability.

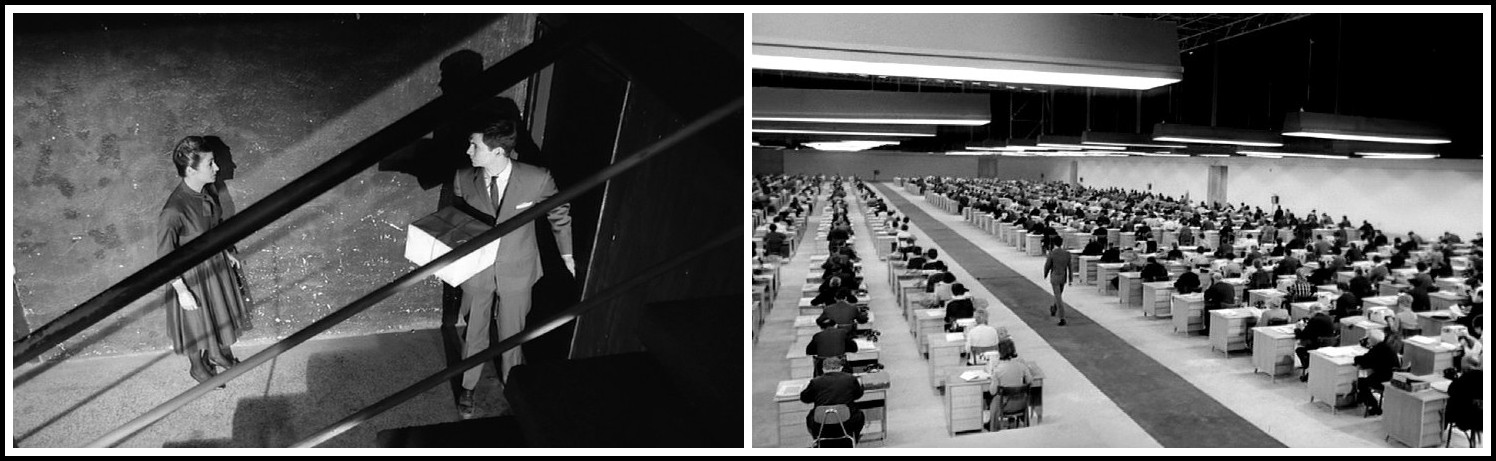

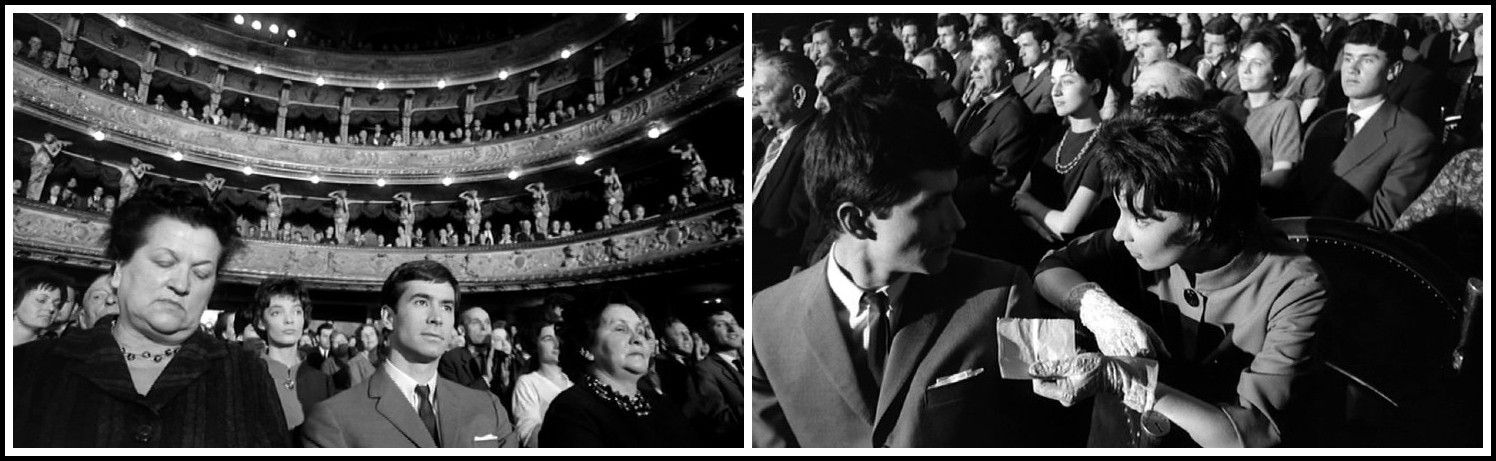

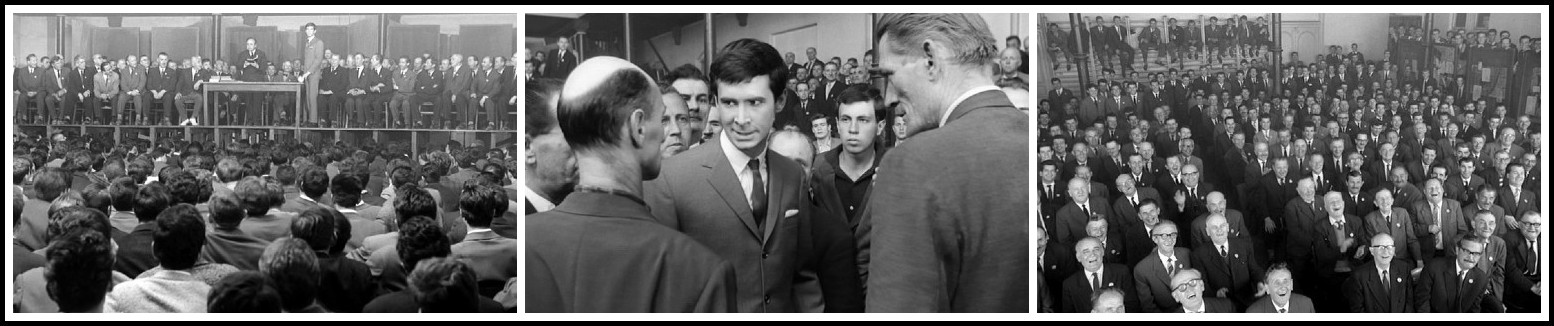

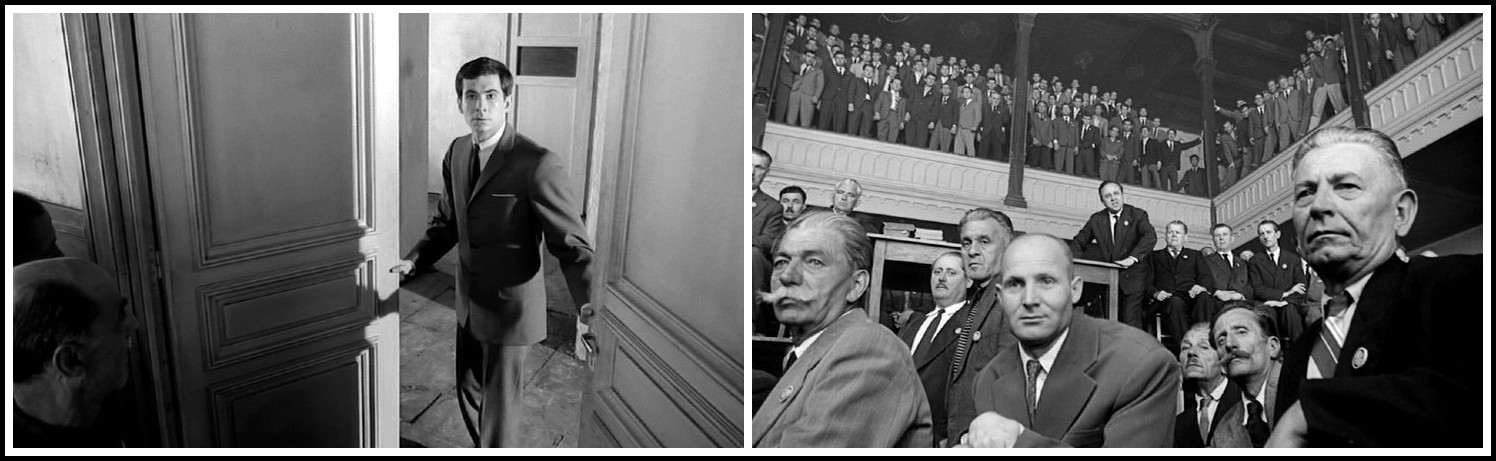

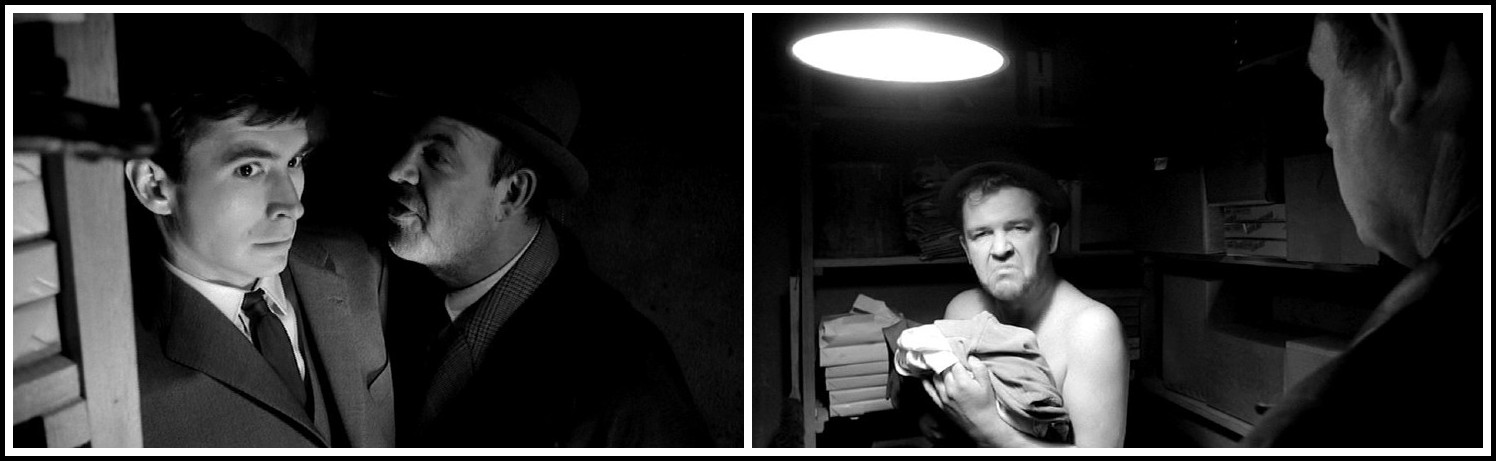

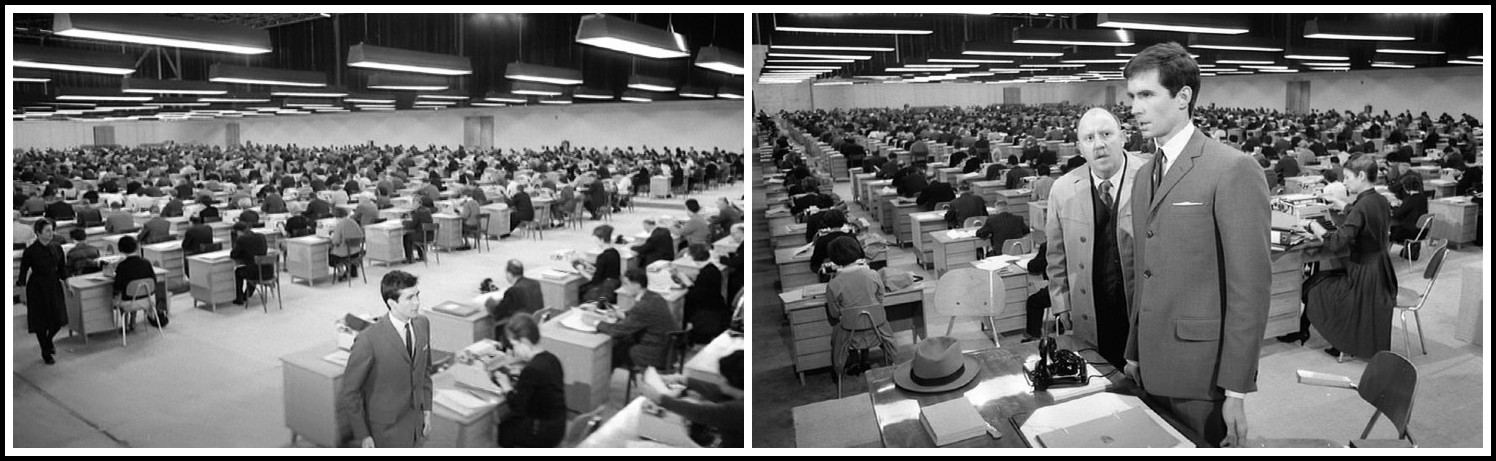

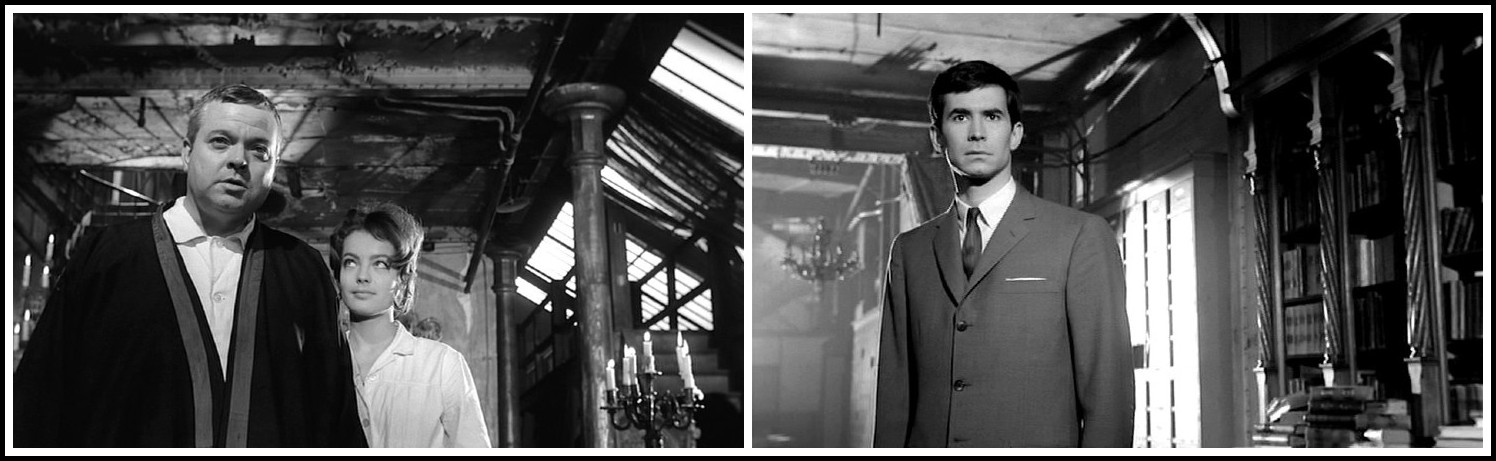

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

I. FAIRYTALE MOTIFS

The quest for a lost paradise, or for some literal or metaphorical treasure, is one of the main types of fairytale. It underlies all three of Kafka’s novels, and is seen at its most fairytale-like in the summation of The Trial, the Parable of the Doorkeeper. The lost paradise in question is that of untroubled consciousness.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The way in which the folk fairytale ‘expresses internal feelings through external events’1 is reflected in Josef K.’s arrest. There are many fairytale precedents for the unsurprised way in which he accepts the presence of the watchmen and, eventually, of his executioners. Like the hero of fairytale, Josef K. finds the right way ‘as if by magic’ when he goes to the Court for the first time, although the magic, if magic it is, is powerless to save him. Kafka first referred to the story of Hansel and Gretel in a letter to Oskar Pollak of 9 November 1903 (‘We are all on our own like children lost in the forest’); he references it again in this novel in the form of the title of one of the pornographic books of the law, ‘The trouble Grete had with her husband Hans’, which subverts the famous fairytale in several obvious ways. The motif of the three drops of blood in the snow in ‘Snow White’, also present in Wolfram’s Parzival, to which there are many apparent references in The Trial, appears as ‘dirt on the melting snow’ outside the building where the painter Titorelli2 lives, a deliberate subversion of the motif, and as such a denial of whatever magic was originally inherent in it. In ‘Snow White’ the three drops of blood in the snow prompt the queen to say ‘Would I had a child as white as snow’; in The Trial the sludge leads Josef K. to a depraved young ‘witch’ whom he inwardly wishes to the devil, and to Leni, whose webbed fingers are, apart from anything else, an example of the ‘tiny flaw’ of fairytale; we return to them presently.

1 – Lüthi, The European Folktale: Form and Nature, tr. J. D. Niles (Indiana University Press, 1982) 15

2 – Cf. not only Titurel, Parzival’s great-grandfather, but also Titeliture, one of the names of Rumpelstiltskin.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

There is, in Josef K. and K., more than a little of the anti-hero who in folklore ‘unerringly hits upon the wrong course of action’.1 The way in which the folk fairytale ‘isolates people, objects, and episodes, and each character is as unfamiliar to himself as the individual characters are to one another’2 is reflected in Josef K.’s lack of self-knowledge and in the reader’s relative lack of knowledge about him and his various ‘helpers’. We know scarcely more of Josef K.’s background than we do of the antecedents of the typical fairytale hero. Unlike fairytales, however, Kafka’s novels have no separate hero and villain; the protagonist is hero and villain in one, with the hero subverted by the villain. The isolation of fairytale characters is paralleled by the isolation of Kafka’s figures, the only relationship between whom is their functional relationship to the protagonist and his inner world: the examining magistrate, Huld, Titorelli and the Priest all relate to Josef K. in the same general way, as well as in various specific ways, but there is no other connexion between them, nor could there be. There is no way in which they could meet, and no locus where they could do so, for every single location in this relentlessly Gothic novel is a reification of Josef K.’s sense of guilt, hence the unremitting sameness of Titorelli’s heathscapes.

1 – Lüthi, The European Folktale: Form and Nature, tr. J. D. Niles (Indiana University Press, 1982) 14f.

2 – Ibid., 43

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

As projections of Josef K., they can, by definition, exist only one after the other; as in fairytale, each new stage of Josef K.’s trial calls forth a new ‘helper’. The subsidiary figures mostly vanish like the helpers of fairytale as soon as they have fulfilled their purpose. Though internalized, many of them are just this, ‘helpers’; this applies, especially, to the main subsidiary figures in the second half of The Trial, each of whom offers K. something tantamount to the ‘gift’ of fairytale in the form of advice that is needed, but which is or seems to be wasted, like the gift offered to the anti-hero of fairytale, although they also have a cumulative effect. Josef K. is more anti-hero than hero. As Lüthi says, ‘The gifts of the folktale are given whenever a particular task calls for them, and they are offered—usually by total strangers—all of a sudden or as a result of an ad hoc relationship that is established quickly and rather sketchily’.1 The relationship between Josef K. and his ‘helpers’ is ad hoc in this sense. It could be argued that he receives the ‘gifts’ he needs as he needs them; but these internalized gifts are potentialities, most of which he proceeds to waste. The formulaic ‘modified repetition’ of phrases (Leni’s ‘That’s all invention’ is followed by Titorelli’s ‘All that’s invention’) is a feature of fairytale, and the calling of the name of Josef K. in the Cathedral takes the reader back to ‘Rumpelstiltskin’, where the calling of the name, for which there are also Biblical precedents, is a magical motif.

1 – Lüthi, The European Folktale: Form and Nature, tr. J. D. Niles (Indiana University Press, 1982) 57

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The Parable of the Doorkeeper, like the story of Amalia’s Secret in The Castle, is pure fairytale, based on the folk fairytale type ‘the quest for the unknown’, as well as going back to numerous tales and myths about journeying to the otherworld. There are many instances of the forbidden-door motif in the novels, but the locus classicus is the Parable of the Doorkeeper, which is particularly close to Andersen, as well as to Grimm, in that the ‘forbidden chamber’ of the Law, from which emanates a seemingly eternal radiance, is reminiscent of the thirteenth chamber in the Grimms’ ‘The Woodcutter’s Daughter’, which contains ‘the Trinity in fire and splendour’: the ‘eternal radiance’ is part of the motif of the forbidden room as such, powerfully underlining the taboo. Such intertextualities suggest that the Man-from-the-Country would have perished if he had had the temerity or folly to enter the chamber that was both open and forbidden to him. Forbidden rooms, which in folklore, with the ambiguity that is even more common in Kafka’s work, may have the connotation not only of Heaven, but of Hell, are liable to contain nasty surprises, as the Bluebeard tales show. The scene in the lumber room in The Trial involves an echo of the Bluebeard tales.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The Parable of the Doorkeeper shows that Kafka also knew and valued Andersen’s work, for it is based on the most famous of Andersen’s early tales and the one closest to folk fairytale, ‘The Tinder-Box’. The tinder-box represents the lost treasure or, in terms of the pattern of allusions in The Trial, the Grail. The gatekeeper/doorkeeper as such is a folk-fairytale stereotype, the threshold a fantasy and folktale motif, and the portal a fantasy motif of great importance. In the parable the doorkeepers, each more formidable than the one before, are clearly based on the dogs guarding successive rooms in ‘The Tinder-Box’, and the gleam of what might or might not be ‘eternal radiance, visible through the doorway to the Law, will have been suggested, in part, by the light from the three hundred lamps in the great hall in Andersen’s story. While in English the radiance in question might just as well be the radiant heat of Hell as the radiant light of Heaven, in German the connotations of ‘Glanz’ are as positive as the epithet, although the ambiguity of the image and its meaning remains. The Man-from-the-Country is a Biblical Philistine or man-of-little-faith, but also, to use the fairytale term, a numskull, the ‘countryman in the great world’ who reveals his folly at every step, as in the Sicilian fairytale in which a ‘numskull’ comes to a river and waits for it to run dry, which of course it never does. There are many such tales. Given his knowledge of Italian and love of fairytale, Kafka may well have come across the tale in question. Spending one’s life waiting to be allowed to enter a doorway, the door of which is all the time standing open, makes no more sense.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Although the Parable of the Door-Keeper is full of fairytale motifs and is itself a literary fairytale, as a whole The Trial is less close to fairytale than the other two novels. This is because at the time Kafka’s imagination was held by ideas which combined to make it the most Gothic of his novels. The ending of the novel, in particular, which comes close to late nineteenth-century Gothic in the death of the ‘vampire’, is far removed from fairytale.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

II. GOTHIC READING – THE INTERNAL TRIBUNAL

The Trial, Kafka’s second novel, written in the second half of 1914, was published posthumously in 1925. When reduced by translation to monosemy and, worse, to the naturalism Kafka eschewed, it seems to be about a forthcoming trial, and therefore to belong in a long succession of ‘trial’-novels stretching back to Godwin’s Caleb Williams (1783-84). However, while the legal ‘machinery’ of the novel may appear to be identifiable with the monolithic, bureaucratic machinery of Habsburg Kakanien in its dying years, there is no reason to think that such a reading would not be a misreading, although bureaucracy could still be one skin of the Kafkaesque onion; there is, for instance, much emphasis on empty form in ‘In the Penal Colony’. Kafka was not, as a writer, interested in politics—the freedom to which he attached such importance was moral freedom, which his view of life at best curtailed and at worst precluded. Besides, consideration of his literary method and use of words and metaphors quickly takes the critical reader beyond the realm of the public and political.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The reader should from the outset be in no doubt that Josef K. is not, as Godwin’s Caleb Williams is, the victim of injustice. The Trial has to do with the constitution and corruption not of society, but of the individual human being; in other words, it has to do not with things as they are, but with Kafka as he was afraid he could become, and with his projective creature, Josef K., as he is. Its moral, if it has one, is ‘Judge Thyself!’ Caleb Williams is a novel of more than one kind, but it is, above all, a political novel in the sense that its author’s intention was to change society. As a public novel, it works dramatically, through the confrontation of one individual with another, whereas The Trial portrays a confrontation with self, a confrontation of the higher self with the lower, a confrontation of super ego and ego, of ego and id, persona and shadow. There is, of course, much more to the novel, and to the Gothic novel, than psychology of whatever ilk, but the psychological dimension and level of meaning of neither can sensibly be ignored.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The Trial can be compared with Caleb Williams, and with Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, in that in the course of it the pursued becomes the pursuer. Leaving aside their symbolic identity for the moment, K. is at first pursued by the minions of the ‘Law’, is ‘arrested’ and told to present himself for a preliminary hearing at such and such a time; but then, initially for the wrong reasons, he becomes the pursuer, increasingly determined to confront his ‘judge’ and force the truth out of him, as indeed he does in a final confrontation with self. However much The Trial may seem to partake of Godwin’s preoccupation with injustice as it ought not to be, it is not a political novel, but a moral, metaphysical and psychological one. And, since it is also, technically, a symbolic novel, its means are very different from Godwin’s. In particular it has a multiplicity of meaning, achieved through a web of metaphors taken literally and developed with legalistic precision, that gives it a brilliance that is different in kind from Godwin’s brilliant psychological penetration and play of ideas. Like Caleb Williams, it was given alternative endings; but while the two endings of Godwin’s novel are totally different, the three alternative endings of The Trial all boil down to the same thing.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Whereas the emphasis in Caleb Williams is on psychological motivation, with the decisive events of the novel, those which trigger psychological change, taking place in public, in The Trial everything takes place in the mind. If both are ‘psychological novels’, they are so in quite different senses. Godwin writes as a social philosopher, Kafka as meta-physician and moral physician, and it is Kafka who arguably wields the ‘metaphysical dissecting knife’, of which Godwin speaks, to the greater metaphysical effect. Godwin believed, passionately, and, it is to be feared, mistakenly, in the perfectibility of Man and hence of human society. For Kafka on the other hand, no less of an idealist than Godwin, and no less concerned with uncovering the wellsprings of human conduct, the individual, let alone that fearfully miscellaneous monster, Society, is far from perfectible, being trapped in a time-warp world of predetermined universal guilt that is theological in origin and psychological in effect. The Trial can be read in more ways than one, although the number of readings appropriately contingent on Kafka’s method, mind-set and preoccupations is limited; but it is neither detective story, nor adventure story, nor Jacobin novel, nor political allegory. For two novels equally concerned with freedom and justice, Caleb Williams and The Trial could in the end hardly be more different. We therefore pass from The Trial as it is not, to The Trial as it is.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Like virtually all Kafka’s work, The Trial is the expression of what he called his ‘dreamlike inner life’. This is what it explores. Any understanding of the novel must begin with the meanings of the word ‘Proceß’ and take into account the implications of Kafka’s spelling of it. The word ‘Prozeß’ (as the title was spelt until 1990, when Kafka’s original spelling of ‘Proceß’ was reinstated) means not only ‘trial’, but ‘(mental) process’ and ‘course (of a disease)’. All three meanings are relevant, the second being fundamental, and the reader also needs to know that when he began writing The Trial Kafka had already had two spells in different sanatoria, although his pulmonary tuberculosis as such was not diagnosed until September 1917. My readings concentrate on other issues, but we need to remember that ill-health, both real and imaginary, was (in English, but not in German) a ‘trial’ for Kafka for much of his life.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

We shall have cause to return to his spelling of the word presently, but first let us consider the famous opening sentence: ‘Someone must have been taking Josef K.’s name in vain, for, without having done anything wrong, he was arrested one morning.’ That ominous, enigmatic opening of The Trial is dramatically Gothic in that it marks the sudden end of the protagonist’s hitherto secure, unquestioning and to that extent unproblematic (though, in this case at least, boorish and mindlessly materialistic) existence, and the beginning of a new, haunted, perpetually challenged and ultimately impossible one. The supposed anonymous denunciation, here purely imaginary, is as it were an internalization of the procedure described in The Mysteries of Udolpho (III, ch. 8), which involved a letter of accusation being placed in the letterbox for Denunzie secrete in the Doge’s palace: ‘As, on these occasions, the accuser is not confronted with the accused, a man may falsely impeach his enemy, and accomplish an unjust revenge, without fear of imprisonment or detection’—a method rightly described as a ‘diabolical means of ruining a person’.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Josef K. is not guilty of any transgression of the civil law, which is simply not in question, or of any particular violation of any symbolic law, or even of any single reprehensible act. In a general way this opening connects with the Letter to His Father, in which Kafka wrote, of his father, that ‘you don’t charge me with anything downright improper or wicked’, for the words ‘anything wicked’ are used in both cases. This autobiographical dimension was underlined when he went on to write, also in the Letter to His Father, of ‘this terrible trial that is pending between us [Franz and Ottla] and you, a trial in which you keep on claiming to be the judge’. We shall return to this in our second reading. The Court is simply a metaphor, elaborated in Kafka’s usual deadpan, often hilarious way, in this case for the workings of the Conscience, for The Trial, like all his punishment fantasies, is less about guilt as such than about a sense of guilt.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Josef K.’s famous awakening is a symbolic one: he awakens to a sense of unease, his conscience slowly filling with a sense first of uneasiness and then of guilt about the thoughtless, materialistic and, in Kafka’s terms, corrupt way in which he has been conducting his life. He has allowed himself to become over-attached (‘verhaftet’ in German, literally ‘arrested’), hence the opening of the novel, in which ‘verhaftet’ is taken literally but meant figuratively, so that Verhaftung stands for Verhaftetsein in the sense of over-attachment (to the world, the flesh and the Devil), in other words, to what Kafka, in aphorism 54, calls ‘the evil in an essentially spiritual world’. Initially Josef K. sees himself as the victim of arbitrary power, as indeed he is on the next reading, though not on this one, and even then not in the most obvious sense. In the course of the novel, which takes up exactly one year of his life, he slowly comes to see himself as a villain. He should know; his own judgment is the only relevant one, and ultimately the only one available to him. If there are no fairytales, there are no miracles and therefore no (accessible) God, let alone a god in a machine.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

To speak of The Trial as lasting a year, and The Castle a week, is, however, largely beside the point, which is that in the revealed subconscious that is their domain, there is no more teleology than there is in dreams: in each case the protagonist has simply had all he can take of the dreadful cyclic disorder that has taken over his life. The whole of The Trial is about the gradual awakening of conscience, the dawning of the idea of transgression against the law of Josef K.’s own existence as a more than animal being, and in that sense moral guilt, but also about existential guilt, for he is guilty not only in the moral terms which he eventually defines in the last chapter of the novel, but also in existential terms. Whether this is described in Christian terms as ‘original sin’, or in Schopenhauerian-Buddhist terms, as the guilt inherent in an existence that comes about as a result of the sexual self-indulgence of others, makes little difference. Kafka came under the spell of Schopenhauer’s mixture of profundity and lucidity, but it was the Fall of Man by which he was still obsessed at this time. Josef K.’s ‘sinfulness’ is tantamount to original sin as defined in the aphorism series Er : ‘Original sin, that age-old wrong done by Man, consists in the complaint that he has been treated unjustly, that he is the victim of original sin.’ In brief, Josef K. is guilty of being who and what he is, and of acting against his own first unconscious, then conscious judgment of how he should have been conducting his life.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Having indicated that Josef K. is guilty, albeit not guilty as charged, it is time to turn our attention to the Court that appears to claim the right to try him, as Kafka’s father is said to have claimed the right to try his son. The Court represents, in the first instance, what Kant, in the Critique of Practical Reason, called the ‘internal tribunal’ of conscience. Kant used an elaborate legal metaphor to describe the workings of conscience, by which he means the knowledge people have about what they have done, in a way which, when applied to it, amounts to a key to The Trial: The consciousness of an internal tribunal in man, before which ‘his thoughts accuse or excuse one another’, is Conscience. Every man has a conscience, and finds himself observed by an inward judge which threatens and keeps him in awe (reverence combined with fear); and this power which watches over the laws within him is not something which he himself (arbitrarily) makes, but it is incorporated in his being. It follows him like his shadow, when he thinks to escape. He may stupefy himself with pleasures and distractions, but he cannot avoid now and then coming to himself or awaking, and then he at once perceives its awful voice. In his utmost depravity he may, indeed, pay no attention to it, but he cannot avoid hearing it. Now this moral capacity, called conscience, has this peculiarity in it, that although its business is a business of man with himself, yet he finds himself compelled by his reason to transact it as if at the command of another person. For the transaction here is the conduct of a trial before a tribunal. But that he who is accused by his conscience should be conceived as one and the same person with the judge is an absurd conception of a judicial court; for then the complainant would always lose his case. Therefore in all duties the conscience of the man must regard another than himself as the judge of his actions, if it is to avoid self-contradiction this other may be an actual or a merely ideal person which reason frames to itself.1

1 – Kant, Critique of Practical Reason and other works on the Theory of Ethics, tr. Thomas Kingsmill Abbott, 3rd edn. (London: Longmans, 1883) 321ff.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

In a footnote Kant explains a man’s dual identity as his own accuser before the metaphorical bar of moral judgment and as his own judge by referring to the distinction between homo noumenon and the rationally endowed homo sensibilis; the fact that in ancient Greek the Devil’s name means ‘an Accuser’, serves to emphasize the fact that Kafka’s own conscience regularly gave him the devil of a time, and that in the course of the novel Josef K., like his predecessor Karl Rossmann, is to go to the Devil. Josef K. is thus identifiable with the Devil both as a ‘devilish person’ and as his own accuser.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

Schopenhauer, in his discussion of ‘Kant’s Doctrine of Conscience’ in The Basis of Morality, presented the following argument: If this tribunal, as portrayed by Kant, really existed in our breasts, it would be astonishing if a single person could be found to be, I do not say, so bad, but so stupid, as to act against his conscience. For such a supernatural assize, of an entirely special kind, set up in our consciousness, such a secret court—like another Vehmgericht—held in the dark recesses of our innermost being, would inspire everybody with a terror and fear of the gods strong enough to keep him from grasping at short transient advantages, in face of the dreadful threats of superhuman powers, speaking in tones so near and so clear. Yet Josef K. seems to be just such a stupid person, for Kant’s account of the workings of conscience, and, if I am not mistaken, Schopenhauer’s analysis of it, provided Kafka with an elaborate model for the ‘court’ in The Trial, a model which links with Gothic in that Kant refers to this internal tribunal or ‘supernatural assize’, as Schopenhauer calls it, as a ‘disguised Vehmgericht that takes place in the mysterious darkness inside us’. The Vehmgericht, let us remember, was an open-air court or tribunal, held in Germany, and especially in Westphalia, from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, for the suppression of crime, notably heresy and witchcraft, at which the death-sentence, the only sentence available to the court, was carried out immediately after an admission of guilt. It is as much a Gothic institution and feature of Gothic as the Spanish Inquisition itself. The way in which the Vehmgericht in effect becomes a metaphor for conscience is an excellent example of Kafka’s internalization of Gothic forms.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The Trial portrays the awakening of conscience and the process through and as a result of which this internal judge or super-ego comes to pass judgment, that is, the way in which Josef K. comes to condemn himself for his egoistical, licentious way of living, which is, of course, a caricature of Kafka’s ‘dissolute’ way of living as seen by his father; a fragment speaks of Josef K.’s (sic) father reproaching him for his ‘dissolute behaviour’ (diary, 29 July 1914), a charge which is reflected in Chapter 5 in the reference to Franz’s marriage plans, which reflect Kafka’s own. There is also a further charge and form of guilt, to which we come in the next section. Much of the novel illustrates the conflict within Josef K.’s mind between his conscience (first personified in the first guard or watchman, Franz, who is seen sitting by the open window because he is a Beisitzer, a member of the court) and his pride (personified in the second watchman, Willem, whose Dutch name derives from the phrase den dicken Wilhelm machen, to boast). The term ‘Behörde’ to denote the authority served by these watchmen is used in its basic sense, that is, as the noun from the verb behören (to listen to, intercept, monitor), and therefore symbolizes the super-ego, the inner monitor or moral censor (or gatekeeper in Freud’s suggestive terminology), to the first unclear promptings of which Josef K. is loath to listen.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

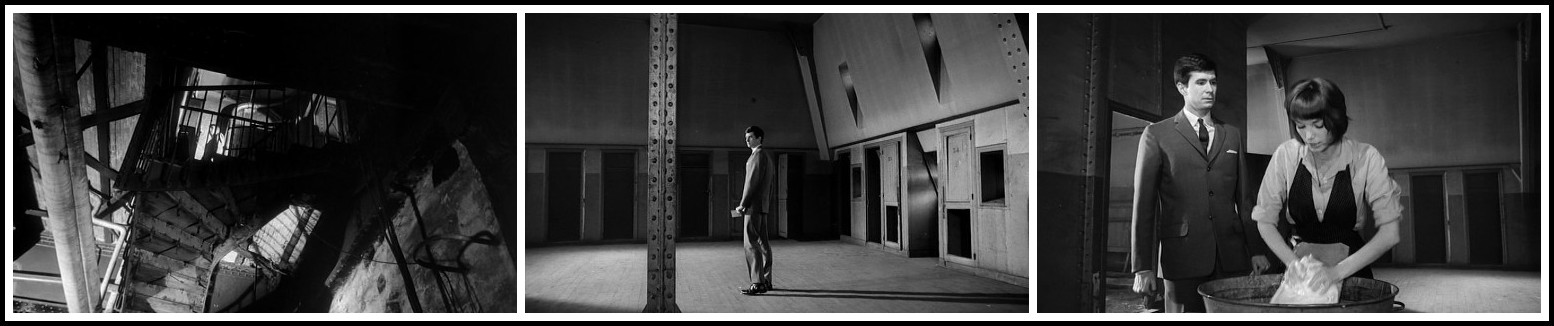

In accordance with the Kantian model and metaphor the attics associated with the court represent Josef K.’s head/mind, in which the whole process is taking place, the corridors representing his thoughts and the progress of his case. Kafka, as usual, simply takes literally the meanings he finds embedded in the language in the form of metaphors which he undoes and embeds within the text.1 Every court-official and judge is accordingly a projection of K. himself, whose whole way of life, he slowly begins to realize, has been a mindlessly selfish one, vulgar and meaningless. Josef K. is shown as literally working in a bank because he is a Bankmensch, a person2 governed by habit rather than thought. The elaborate legal metaphor or fiction of K.’s impending ‘trial’ is continued in the second chapter, when he is seen going off to ‘court’ to attend a preliminary hearing of his case, but it is the figurative meaning of the phrase mit sich selbst ins Gericht gehen (to take oneself to task) that explains the ‘court’, for Josef K. is his own accuser and therefore the devil in question. Kafka simply takes the phrase literally and shows Josef K. going off on his own to the court which represents3 K.’s first unconscious and eventually conscious sense of guilt. His first examination by an examining magistrate is accordingly a self-examination, the first of several; it cannot be otherwise. The examining magistrate, who is found sitting behind an appropriately small table, for this is the lowest court, is described as a fat, wheezing little man who every now and then gesticulates as though he were caricaturing someone. This magistrate is in fact a caricature of Josef K., who is insignificant, proud4 and out of his element in the domain of the conscience he hasn’t used for years.

1 – Haus = Mensch: house = human being (man); Dach/Dachboden = Kopf: attic = head, mind). Freud drew attention to this meaning, via the phrase einem eins aufs Dachl geben (to hit someone on the head), in his Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis, where he also noted that in German, an old acquaintance is often addressed as ‘old house’ (altes Haus). The latter term is equivalent to ‘old man’, which includes ‘my old man’ (father).

2 – In the German of the time, modern Gewohnheitstier.

3 – The reader is, as usual, left to work out Kafka’s meaning, for part of the metaphor is suppressed.

4 – ‘dick’, cf. Willem

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The washerwoman to whom Josef K. feels momentarily attracted is both a projection of his own libido and a personification of the phrase das kannst du der Wascherin erzahlen (tell that to the marines), the reference being to the unlikely story (fairytale) of his innocence. Another projection of his libido is the red-bearded (diabolical, lecherous) student Berthold (Josef K. is, of course, the only real student—of the court and its proceedings—in the novel), of whom the ‘Gerichtsdiener’ (Josef K.’s super-ego) says that what he needs is a good thrashing, which is precisely what he gets in a symbolic sense in Chapter 5. This key chapter, the turning-point of the novel and a classic example of the uncanny;1 is a punishment dream pointing forward to another, intensified such dream in the form of the final chapter of the novel.

1 – S. S. Prawer, Caligari’s Children: The Film as Tale of Terror (Oxford University Press, 1980) 136

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

A particularly interesting symbol of libido is Leni, who embodies what Kafka called die geplatzte Sexualität der Frauen (the sexuality with which women are bursting; platzen means to burst or smash); he takes his own phrase literally when he has Leni throw a plate at the wall in order to attract Josef K.’s attention. Leni’s physical defect, her webbed hand, Josef K. calls ‘eine hubsche Kralle’ (a fine claw), which identifies her as one of the sirens—the classical personalization of woman as snare—who recur throughout Kafka’s work and whose claws are featured in one of the less known stories, ‘The Silence of the Sirens’.1 The voice of the siren that features in K’s attack of ‘sea-sickness’ in the empty courtroom points forward to Leni, who is also identifiable with Josef K., standing for his habit of following the line of least resistance in his thoughts, which tend to revolve around women and the sensuality Kafka associates with them, so that she also represents Josef K.’s libido. When he remarks to the Priest (ch. 9) that the Court consists almost entirely of ‘Frauenjäger’ Josef K. is , on one level, referring to his own skirt-chasing or petticoat-hunting proclivities, but his words have another meaning, to which we will come presently, for Kafka avoids the usual ‘Schürzenjäger’ in favour of a word which has a more literal meaning and, with it, a more ominous implication.

1 –Cf. the 1917 diary-entry in which he wrote ‘again and again the clawed hands of the siren struck at my chest’.

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

While he is in the Cathedral, waiting, without realizing it, for the Priest to appear, that is, waiting as it were for his own thoughts to pass from the aesthetic to the spiritual, Josef K. wanders off to a side-chapel in which he sees one of the many remarkable pictures in the novel. Since The Trial is the exposition of a mental process, dreamlike in its ‘regressive translation of thoughts into images’, it is natural that pictures, concentrated pictorializations, should occur at important stages in the process it describes. The present ‘Entombment of Christ’ is necessarily symbolic. The foreground-figure of the great knight in armour at the extreme left of the picture is a mirror-image of Josef K., who in his subconscious mind’s eye visualizes himself, self-importantly, as a knight in armour because even at this late stage he is still deluding himself, still thinking evasively, still picturing himself as fighting the good fight against a corrupt legal system. The knight prefigures the man-from-the-country in the soon to be related Parable of the Doorkeeper in that he too stands idly by. K.’s idea that the knight is perhaps appointed to stand guard seems an inept notion since the fact that his sword is stuck in the ground suggests that he is not on guard at all, although he should be, as should Josef K., for whom he stands. ‘Watch’ is synonymous with ‘watcher’, so the knight also points back to the beginning of K.’s ‘Proceß’ and forward to the Parable of the Doorkeeper. The process which this conspicuously slothful knight is watching is the entombment of Christ (by Joseph of Arimathea). Entombment, of course, has Gothic connotations. The prime function of this picture is to foreshadow Josef K.’s death: he is foreseeing his own entombment (inhumation).

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

The Parable of the Doorkeeper turns on the man-from-the-country’s lack of faith: if he had believed in the Law, he would not have insisted on seeing it with his own eyes. Applied to Josef K.’s case, which it is intended to illustrate, the Parable of the Doorkeeper means that if K. had believed in his own innocence, he would not have felt it necessary to prove it. Following the dramatic dialogue with the Priest, who represents his higher self (Kant’s homo noumenon), Josef K. (Kant’s homo sensibilis) finally has no choice but to condemn himself to death because he is incapable of living in any other way and is implicitly unwilling to face the ‘demon of insanity’ faced by Stanton in Melmoth the Wanderer.1 The most significant event anywhere in Kafka’s novels is the closing of the door in the Parable of the Doorkeeper. The Trial opens with the symbolic closure of Josef K.’s hitherto untroubled existence, and the pattern, once established, continues throughout the novel, as it did in the previous novel and will do in the next one, each closure a foreclosure, a putting away of what has been. What counts, now, is not the weekly visit to Elsa by which Josef K. used to define himself, but the subjection to death that is the real meaning of his physicality.

1 – C. R. Maturin, Melmoth the Wanderer, 3 vols (London: Richard Bentley & Son., 1892), 1, 88

Orson Welles, The Trial, Franz Kafka

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments