Didactic Ambition Gets the Better of Poetic Success

LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER: D.H. LAWRENCE WRITING THE EROTIC

Maurice Couturier

Translated here by Richard Jonathan

From Maurice Couturier, Les Ruses d’Éros: Chronique du roman moderne (Paris: Orizons, 2020) pp. 153-167

J.S. Sargent, Mr. & Mrs. Phelps Stokes, 1897 | Albert von Keller, Adele von Le Suire, 1887 | Edvard Munch, Ellen Warburg, 1905

I. INTRODUCTION

The slow freeing of minds and morals that occurred at the beginning of the twentieth century, and not only under the influence of Freud, encouraged authors to express themselves more freely on sex, which, increasingly, had been recognized as a structuring component of the subject. The publication of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Florence in 1928 embodied, for better and for worse, this evolution. D.H. Lawrence rejected not only the puritan discourse on sex but also the libertarian discourse of European Bohemia: They have apparently killed the dirty little secret, but somehow, they have killed everything else too. Some of the dirt still sticks, perhaps; sex remains still dirty. But the thrill of secrecy is gone. Hence the terrible dreariness and depression of modern Bohemia, and the inward dreariness and emptiness of so many young people of today. They have killed, they imagine, the dirty little secret. The thrill of secrecy is gone. Some of the dirt remains. And for the rest, depression, inertia, lack of life. For sex is the fountain-head of our energetic life, and now the fountain ceases to flow.1 Lawrence, like Hemingway, saw sexuality in terms of energy, hence his severe criticism, in the same essay, of masturbation, which he considered to be a waste of that energy outside of any love relationship. In Lady Chatterley’s Lover, he strove to break free of censorship, to express his conception of sexuality directly, and to marry, so to speak, the sensual primitiveness of a gamekeeper with the frustrated sensuality of an aristocratic woman. Unfortunately, as we shall see, didactic ambition too often got the better of poetic success, a fact paradoxically confirmed by most of the participants in the trial of the novel.

1 – D.H. Lawrence, The Bad Side of Books: Selected Essays of D.H. Lawrence (New York Review Books Classics, 2019). Kindle Edition.

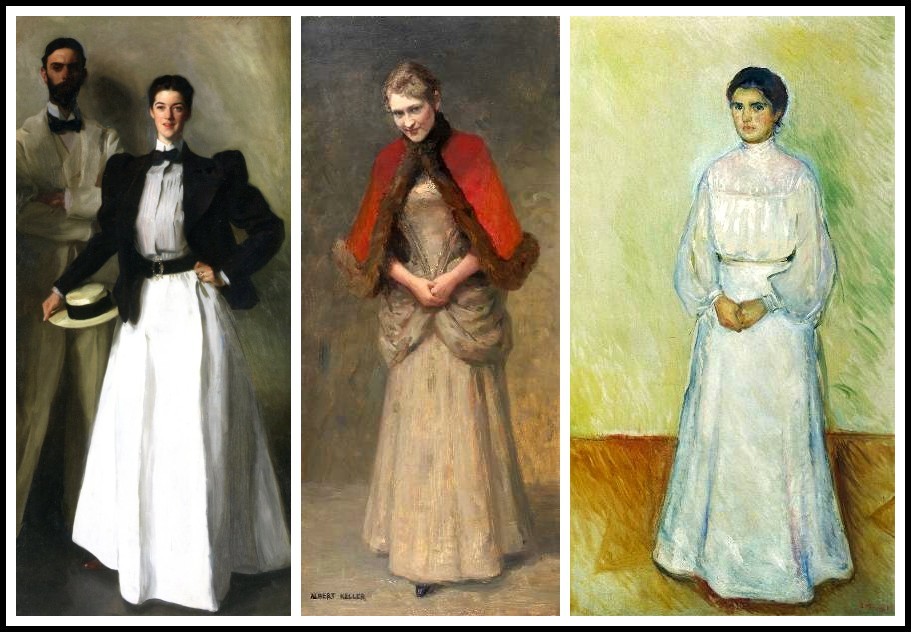

René Magritte, The Lovers, 1928

II. LADY CHATTERLEY’S LOVER: D.H. LAWRENCE AS SEXOLOGIST OF ‘GOOD SEX’

The moralizing and didactic vision of sex is on display right from the opening of the novel: Ours is essentially a tragic age, so we refuse to take it tragically. The cataclysm has happened, we are among the ruins, we start to build up new little habitats, to have new little hopes. It is rather hard work: there is now no smooth road into the future, but we go round, or scramble over the obstacles. We’ve got to live, no matter how many skies have fallen. This was more or less Constance Chatterley’s position. The war had brought the roof down over her head. And she had realized that one must live and learn. The modal expression Lawrence introduces (‘more or less’) clearly shows that it is not the character but an omniscient narrator who is responsible for the text, a narrator—in fact the author—who, throughout the novel, will assume the role of one who, overseeing the text, has the last word.

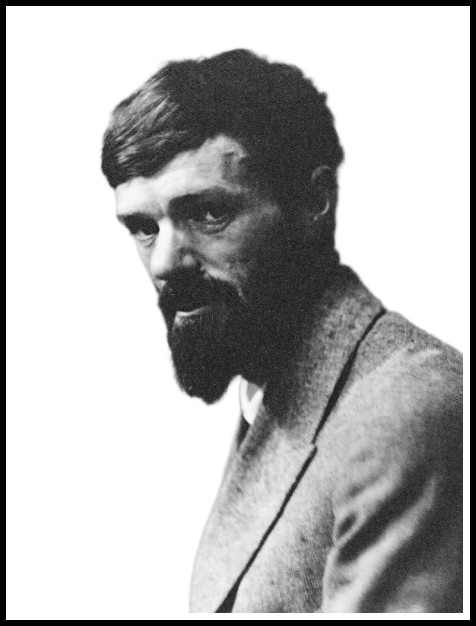

Edward-Weston, D.H. Lawrence, 1924

The first sexual experiences evoked in the novel, namely the initiation of the two sisters, the relations between Connie and her husband after the marriage, or between Connie and Michaelis since the crippling of her husband, are described relatively discreetly yet already explicitly. Here, for example, is the description of the sexual relations between Lady Chatterley and Michaelis: But then she soon learnt to hold him, to keep him there inside her when his crisis was over. And there he was generous and curiously potent; he stayed firm inside her, giving to her, while she was active… wildly, passionately active, coming to her own crisis. And as he felt the frenzy of her achieving her own orgasmic satisfaction from his hard, erect passivity, he had a curious sense of pride and satisfaction. The sexual mechanics are described in a falsely abstract manner: ‘crisis’, ‘potent’, ‘hard, erect passivity’. The formulation, however, is more explicit than that found in Lawrence’s previous novels. In Women in Love, even though the sexual relations between Gudrun and Gerald are very tumultuous, the sexual mechanics are only described indirectly, often metaphorically, to such an extent that in certain scenes one wonders what exactly is happening between the lovers. Lawrence knew, given the problems he had with censorship when The Rainbow was published, that he could not describe the sexual scenes too explicitly; he made up for that in Women in Love by evoking, in a hyperbolic strain, the feelings and sensations of the characters, leaving it to the reader to imaginatively reconstitute the scene.

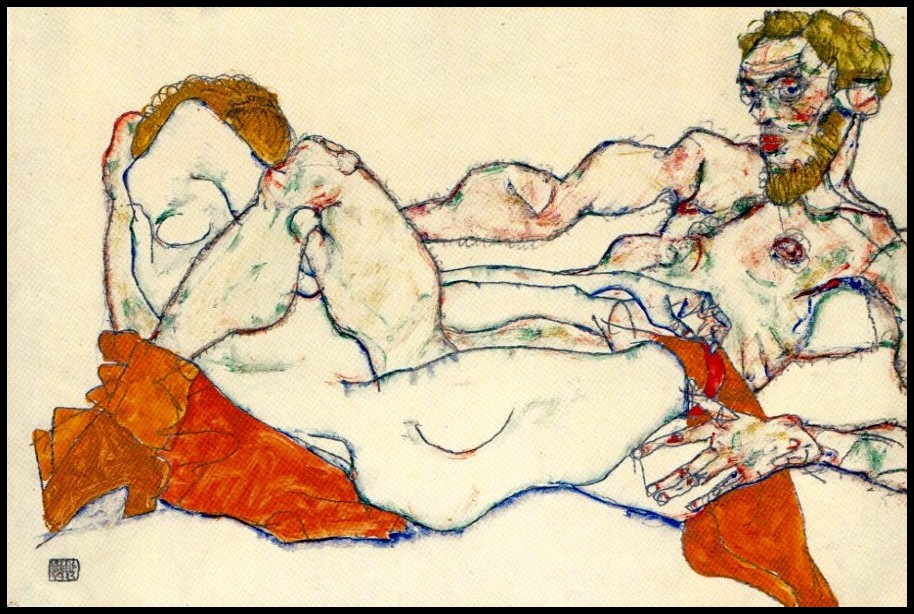

Egon Schiele, Reclining Male and Female Nude, Entwined, 1913

The passage in Lady Chatterley’s Lover cited above is focused less on Michaelis himself than on his thinking phallus. Via that amazing ellipsis, we clearly see the author’s hesitation about describing the woman’s sensations, a hesitation in the form of a plea addressed to the woman: what do you desire? This question is not asked by Michaelis, who is only passing through Connie’s (Lady Chatterley’s) life, but by the author himself; he is using the male characters as instruments in an attempt to drag an answer out of an archetypal woman.

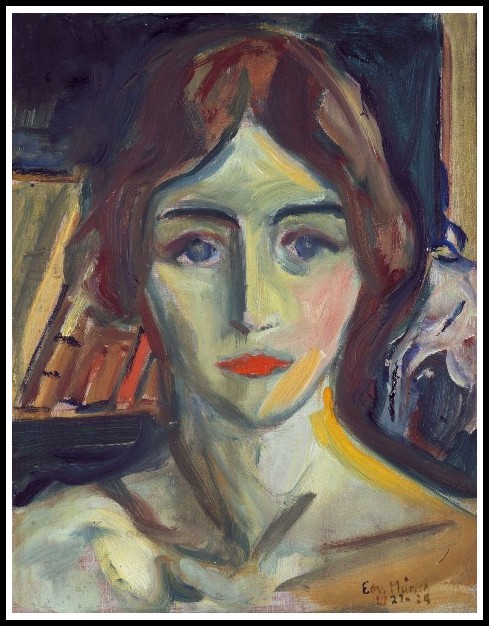

Edvard Munch, Birgit Prestøe – Portrait Study, 1925

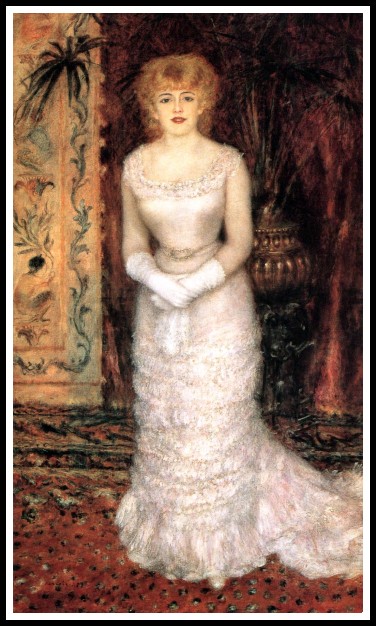

Lawrence, taking up in part the Freudian thesis, will deploy an elaborate phallic liturgy in order to prove throughout the novel that the woman’s object of desire is the penis. After the first erotic scenes, he stages a scene with a group of intellectually-inclined men holding forth on the subject. Tommy, who complains about being impotent, expatiates philosophically on the intelligence of the penis: It would be wonderful to be intelligent: then one would be alive in all the parts mentioned and unmentionable. The penis rouses his head and says ‘How do you do?’ to any really intelligent person. Renoir said he painted his pictures with his penis; he did too, lovely pictures! I wish I did something with mine. God! When one can only talk! This disillusioned speech is punctuated by Connie who, having listened in silence to the whole conversation, expresses her own point of view: ‘There are nice women in the world,’ said Connie, lifting her head up and speaking at last. Her remark makes the men ill-at-ease. In this passage, as in several others, Lawrence accuses intellectuals of having intellectualized sex and thereby of having brought about their own impotence. In Tommy’s complacent speech, we paradoxically see the emergence of the ideal that Connie and Mellors will later realize: the penis is not just an organ but a living being endowed with a will and an intelligence that condemn its master to slavery.

Renoir, The Actress Jeanne Samary, 1878

In his denunciation of intellectuals who know how to speechify about sex but are incapable of having satisfying sexual experiences, Lawrence shows a certain hypocrisy, since his whole novel is itself a long speech about sex. He is forced to use language to deliver his condemnation of a discourse he considers incapable of capturing the reality of a relationship, in this case an erotic rather than a love relationship. He grapples with the language he accuses of always betraying the real, without realizing that in fact he is struggling with himself, with the censorship that he unknowingly imposes on himself and with his inability to create an authentically poetic discourse on sex. Never does he come to understand that the most tyrannical censorship is self-censorship: in vain he went into exile or fled to the margins of society, he could not escape this law. The only way to attenuate the rigour of it would have been to create a narrative and poetic technique sufficiently convincing to put the reader, charmed by the writing, in a position to find himself confronted with his own embarrassment and desire Such a prowess was achieved by, for example, Flaubert, Joyce and Nabokov. Lawrence’s writing, unfortunately, was too didactic: his own desires and frustrations as an author show through it.

Nickolas Muray, D.H. Lawrence, 1923

To ward off self-censorship and truly challenge the reader, Lawrence adopts a strategy of erotic escalation similar to that found in pornographic fiction. After his staging of the ‘frustrated intellectuals’ scene, he proceeds to write a series of increasingly explicit scenes that culminate in the famous morning scene. He begins by describing Mellors, the gamekeeper, as if he were a living phallus, using Connie as a reflector: She saw the clumsy breeches slipping down over the pure, delicate, white loins, the bones showing a little, and the sense of aloneness, of a creature purely alone, overwhelmed her. Perfect, white, solitary nudity of a creature that lives alone, and inwardly alone. And beyond that, a certain beauty of a pure creature. Not the stuff of beauty, not even the body of beauty, but a lambency, the warm, white flame of a single life, revealing itself in contours that one might touch: a body! She sees not the gamekeeper but an ideal object, the ideal of her desire as an autonomous phallus, eminently desirable. The elliptical syntax of the passage, after the first sentence, blurs the gap between the thought of the character and the quasi-philosophical reflection of the author articulating this rather abstract discourse. The impersonal formulation, in conjunction with the modalization, is an epiphany that the two characters seem to share in the same instant. In this phallic ecstasy, the male author and his female character are in perfect harmony, both forgetting the intermediate character at the origin of this reverie. This might recall the ‘fucking’ scene in Madame Bovary, except that it lacks the poetic distance that left Flaubert’s text in a quasi-free-floating state. Here, Lawrence uses a technique akin to that found in pornographic novels.

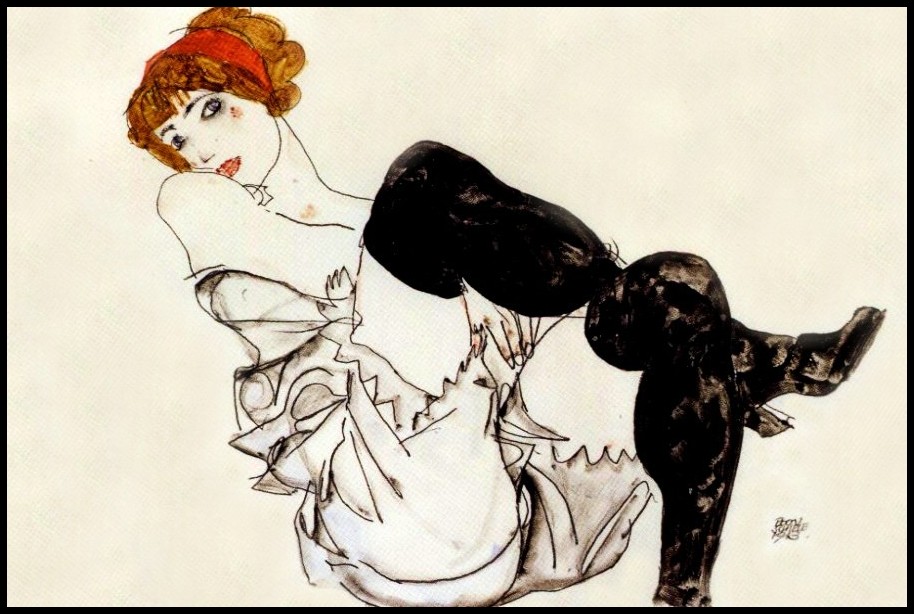

Egon Schiele, Woman in Black Stockings, 1913

How can we not compare this description of a phallus-made-man with that adolescent penis described in luxurious detail in Fanny Hill? Yet I could not, without pleasure, behold, and even ventured to feel, such a length, such a breadth of animated ivory! Perfectly well turned and fashioned, the proud stiffness of which distended its skin, whose smooth polish and velvet softness might vie with that of the most delicate of our sex, and whose exquisite whiteness was not a little set off by a sprout of black curling hair round the root. Fanny Hill is in ecstasy before this innocent penis that hitherto had not known it was so desired and in which, indeed, she recognizes the ideal of her own desire. Only a few traces of self-censorship remain in Cleland’s text; in contrast, in the passage from Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Connie’s embarrassment is obvious, especially in the exclamation ‘a body!’, the impersonality of which foreshadows the depersonalization of Mellors and the abstraction of his body into a concept. Lawrence struggles desperately to detach his own desire from that of his characters, but he never really manages to do so.

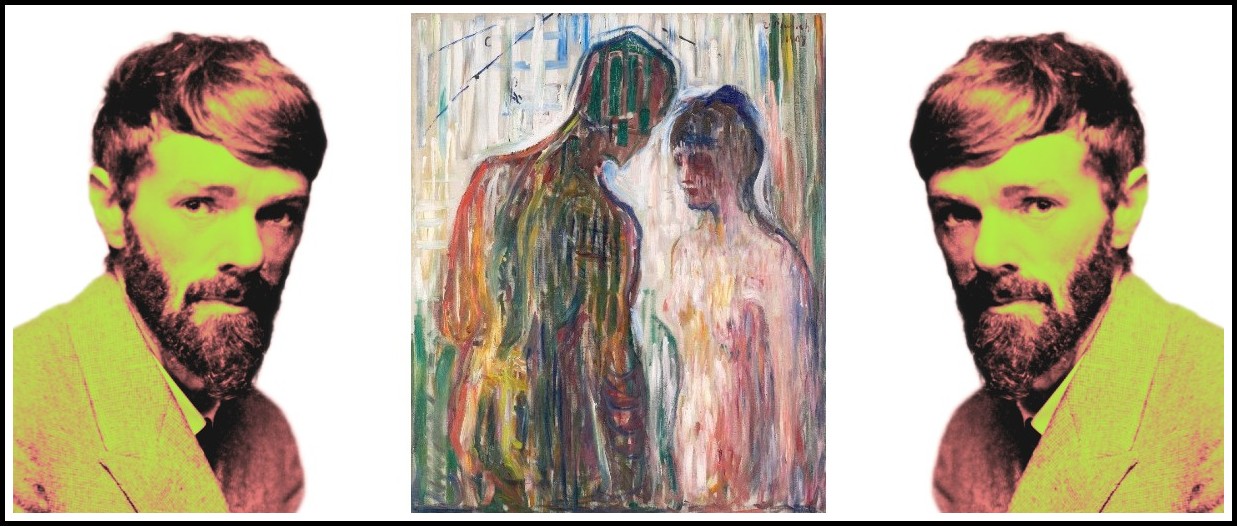

D.H. Lawrence | Edvard Munch, Cupid and Psyche, 1907

In the sexual scenes that follow, Lawrence strives to eliminate the layers of abstraction that cover the male sexual organ as a phallus and prevent its description as a penis, but he fails to overcome the obstacle of inexpressibility that poetically characterizes it in the realm of fiction. When one examines successively the love scenes between Connie and Mellors, one realizes that the issue, indeed, is not so much the increasing harmony between the two lovers but rather the increasingly explicit verbalizing of sexual mechanics, with particular emphasis on their ‘showpiece’. Here is a fragment of the first scene: Then with a quiver of exquisite pleasure he touched the warm soft body, and touched her navel for a moment in a kiss. And he had to come in to her at once, to enter the peace on earth of her soft, quiescent body. It was the moment of pure peace for him, the entry into the body of the woman. Connie, who is the main reflector character throughout the novel, partially ceases to be so at this crucial moment. If one might have been able to believe at the beginning that this passage represented the thoughts of the woman who feels she is a stranger to the man’s pleasure, one understands at the end that the author has tried to objectify the scene and thereby to confer upon it a voyeuristic dimension. It is here that one perceives the pornographic turn in Lawrence.

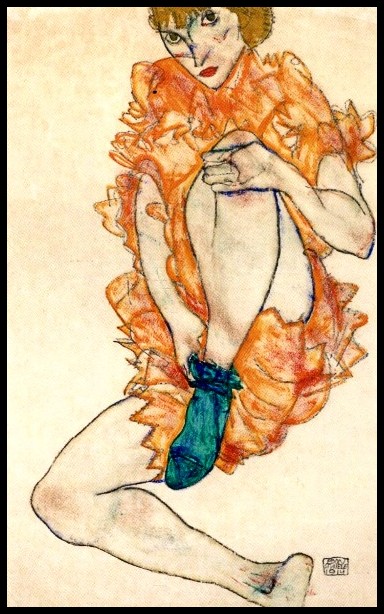

Egon Schiele, The Green Stocking, 1914

In the passage that immediately follows this scene, Mellors becomes for a moment the reflector; he seems to adopt the phrase that closes the passage just cited (‘the woman’): The woman! If she could be there with him, and there were nobody else in the world! The desire rose again, his penis began to stir like a live bird. At the same time an oppression, a dread of exposing himself and her to that outside Thing that sparkled viciously in the electric lights weighed down his shoulders. She, poor young thing, was just a young female creature to him; but a young female creature whom he had gone into and whom he desired again. Those electric lights symbolize the materialist society depicted just before this scene, the society hostile to the open display of desire.

Egon Schiele: Seated Woman with Bent Knee, 1917 | Self-Portrait with Outstretched Arms, 1911

Mellors demonizes his penis (dread of the malevolent Thing outside) and returns it to its abstract status as a phallus. The equivalence between the penis and the body of the woman he desires is, moreover, emphasized by his designation of Connie as a poor young thing. This common noun indicates the inexpressible, the ideal object of desire. Mellors’ phantasmatic self-censorship (thus outside of discourse) does not conceal the author’s embarrassment in designating the penis-phallus and his fear of writing a pornographic work. Lawrence thus finds himself confronted with a poetic challenge from beginning to end: how to describe the most concrete element of sexual mechanics without succumbing to the most vulgar pornography which, in ‘Pornography and Obscenity’, he claimed to utterly despise? In an attempt to guard against this risk, he strives, without much success, to replace in his descriptions the anatomical organ with its symbolic and abstract equivalent, the phallus.

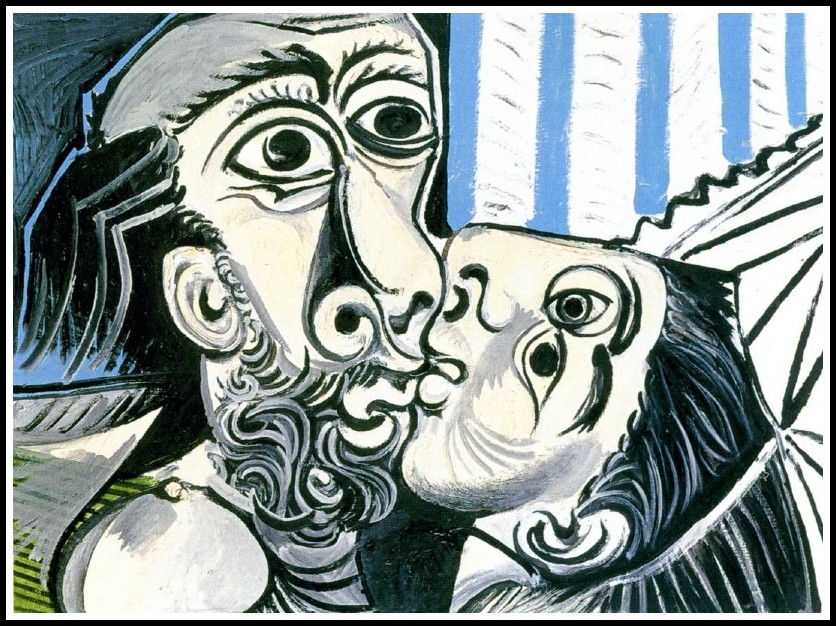

Picasso, The Kiss, 1969

Lawrence was partially right to claim, in Fantasia of the Unconscious, that discourse on sex (which can never be a discursivisation of sex) ends up making sex insipid. This did not prevent him, as Lady Chatterley’s Lover shows, from constantly violating this principle. He asks himself the same question that Narcissus at the edge of his pool of water asked: Who am I? He feels himself inhabited, like everyone does, by something at once intimately personal and strangely foreign: his own desire. Desire’s essence is ontological, but, via anatomical concretization, Lawrence tries to flush it out without realizing that desire’s roots lie elsewhere, namely in the unconscious. He thus imposed upon himself a dual constraint: to express the inexpressibility of sex, and, thereby, to sign a pact with censorship despite having intended to storm its barriers.

Ernersto Guardia, D.H. Lawrence, 1929 | Caravaggio, Narcissus, 1598

Unlike Flaubert, Lawrence is incapable of poetically representing, effectively, a woman’s desire and pleasure. Connie’s first orgasm is described in terms of an appropriation of the penis: She clung to him unconscious in passion, and he never quite slipped from her, and she felt the soft bud of him within her stirring, and strange rhythms flushing up into her with a strange rhythmic growing motion, swelling and swelling till it filled all her cleaving consciousness, and then began again the unspeakable motion that was not really motion, but pure deepening whirlpools of sensation swirling deeper and deeper through all her tissue and consciousness, till she was one perfect concentric fluid of feeling, and she lay there crying in unconscious inarticulate cries. The voice out of the uttermost night, the life! The man heard it beneath him with a kind of awe, as his life sprang out into her.

Brassaï, Phénomène de l’extase, 1933

Lawrence believes he can express the woman’s pleasure, but, when all is said and done, he only projects onto Connie his own narcissistic fantasies: the idealization of the experience does not hide the fact that Connie herself remains imprisoned in her own narcissism and is incapable of having a true love relationship. She uses her partner’s penis, she appropriates it, but that does not mean she feels any closer to him. This, indeed, is what comes out in one of her dreams shortly after: So, in the flux of new awakening, the old hard passion flamed in her for a time, and the man dwindled to a contemptible object, the mere phallus-bearer, to be torn to pieces when his service was performed. The myth of the vampiric woman reappears once again in Lawrence: the desire of the woman is not the desire of the man; instead, it is the desire to castrate the man. Why, Lawrence seems to protest, does the woman not passionately desire the emblem of my own desire? Narcissus as a child does not express himself otherwise.

Brassaï, Fille dans un hôtel de passe, rue Quincampoix, Paris, 1932

From this passage forward, Lawrence shows how Connie will gradually discover the beauty of the penis and fall in love with it. During an episode of intercourse she finds unsatisfying, she wonders, with a certain disdain, about the puerile anxieties of the penis: The butting of his haunches seemed ridiculous to her, and the sort of anxiety of his penis to come to its little evacuating crisis seemed farcical. Yes, this was love, this ridiculous bouncing of the buttocks, and the wilting of the poor, insignificant, moist little penis. This affirmation is in fact a question: What link can there possibly be between this ridiculous organ and this feeling—so marvelous, so intense—that is love? A few pages further on, after having come, her feelings about the penis begin to change: The unspeakable beauty to the touch of the warm, living buttocks! The life within life, the sheer warm, potent loveliness. And the strange weight of the balls between his legs! What a mystery! What a strange heavy weight of mystery, that could lie soft and heavy in one’s hand! The roots, root of all that is lovely, the primeval root of all full beauty. Here Lawrence attributes to his protagonist a hyperbolic discourse in order to signify the inexpressible character for her (and for himself) of the male organ, admitting his incapacity to poetically conquer that inexpressivity. Each exclamation (there are twelve in the paragraph) is like an invitation addressed by Lawrence to his reader-voyeur to imagine what his character feels, but that he, as a writer, is incapable of expressing in words.

Jean-Jacques Annaud, L’Amant, Marguerite Duras

This idealization of the penis reaches its apogee in the famous morning scene that drew the wrath of the censors. Mellors, stark naked, has gotten up to close the curtains; he doesn’t dare to turn around because of his aroused nakedness. He had not, hitherto, shown any such reticence before Connie; now he suddenly discovers shame: having caught his shirt off the floor and held it to him, he now becomes, because of this very modesty, strangely desirable in the eyes of Connie. She asks him to turn around: He dropped the shirt and stood still looking towards her. The sun through the low window sent in a beam that lit up his thighs and slim belly and the erect phallus rising darkish and hot-looking from the little cloud of vivid gold-red hair. She was startled and afraid. The staging of the scene might appear overdone; the borrowing from pictorial—even photographic—technique is obvious. Here we have the type of scene that will seem totally obscene to some and wonderfully erotic to others. Several factors influence readers’ judgement: their degree of familiarity with erotic literature, their moral biases, their type of sensuality and their poetic expectations. Compared to traditional erotic literature, this passage has an undeniable poetic dimension.

Brancusi, Princess X, 1916

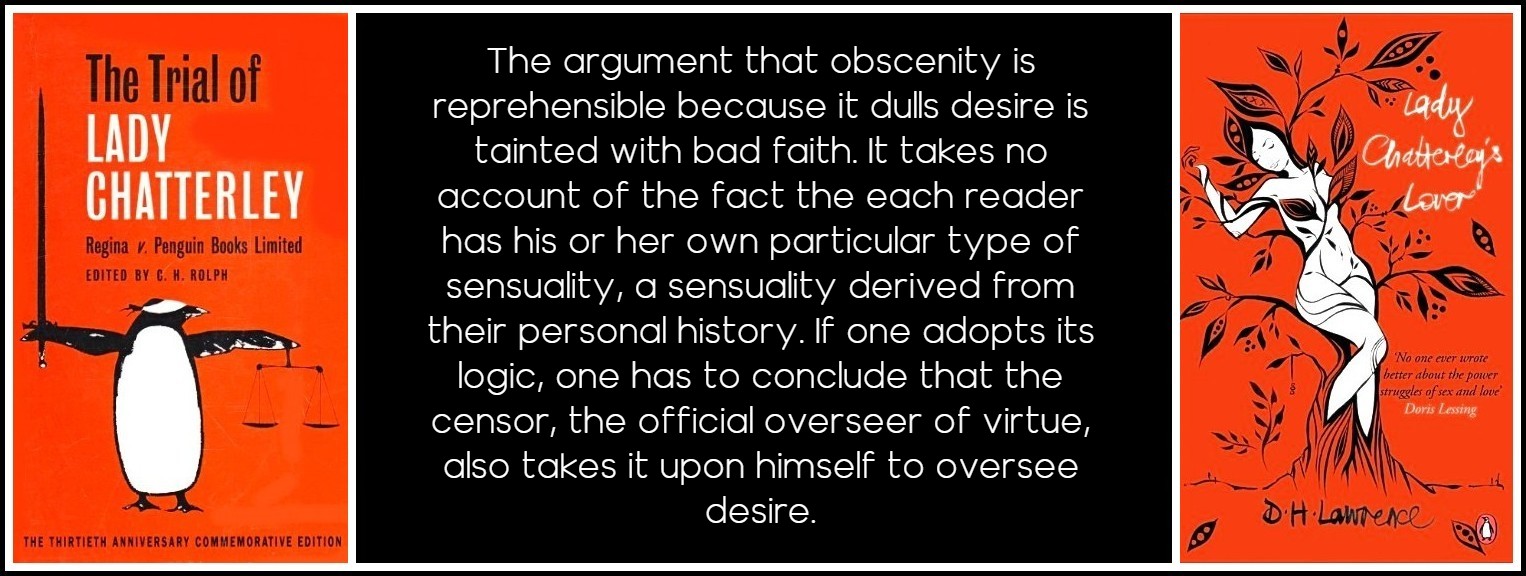

It remains too explicit, however, for prudish readers who rationalize their priggery as a resistance to habit, as researchers have shown: Here is the wisdom of sexual modesty. The breasts are concealed in order to maximize their capacity to arouse when revealed during intercourse. The argument can be extended to include the concealment of the genital organs. The man resorts to modesty in order to prevent habit from attenuating his sexual potencey.1 Obscenity is said to be reprehensible not only because it might incite weak individuals to act out their response to it but also and especially because it dulls desire. This argument, tainted with bad faith, takes no account of the fact the each reader has his or her own particular type of sensuality, a sensuality derived from their personal history. If one adopts its logic, one has to conclude that the censor, the official overseer of virtue, also takes it upon himself to oversee desire. Lacan would have approved this thesis, for had a monist vision of desire and asserted that the law that orders the individual to desire is of the same nature as the law that forbids certain behaviours considered immoral. This complicity between psychoanalysis and puritanism would not have surprised Michel Foucault.

1 – D. Zillmann & J. Bryant, ‘Effects of massive exposure to pornography’ in N. W. Malamuth et E. Donnerstein, eds., Pornography and Sexual Aggression (New York: Academic Press, 1984) p. 197. Freely back-translated here.

D.H. Lawrence, Lady Chatterley’s Lover, Trial for Obscenity

To complete the explanation of why judgements of the passage in question differ so widely, another important factor needs to be considered: the reader’s poetic expectations, which partly depend on his personal critical competence and his previous reading experiences, even if they are always linked, one way or another, to the promises made by the text/author. On this point, of course, one must take into account the novel in its entirety. The passage under study compared to the preceding ones represents real progress: in it, Lawrence has created a more appealing and more erotic image for the majority of readers insofar as it demands a rather greater effort of imagination. This image is also a sign that Connie has abandoned her vampiric feelings towards the male organ and that she has recognized in it the ultimate object of her desire.

Required for reading D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover: Critical Competence, Experience, Imagination | Getty Images & Unsplash

The concretization of this discovery occurs a few lines further on: ‘Oh, don’t tease him,’ said Connie, crawling on her knees on the bed towards him and putting her arms round his white slender loins, and drawing him to her so that her hanging, swinging breasts touched the tip of the stirring, erect phallus, and caught the drop of moisture. For Constance the question is no longer to appropriate the male organ, but rather to establish an intense erotic relation with it. After the sexual effusions of the preceding chapters, all of which fail to erase the inexpressivity of sex and the author’s embarrassment, this passage is a poetic success: hyperbolic discourse is replaced by an erotic gesture hitherto not found, perhaps, in literature, erotic or otherwise. Except for the reference to ‘phallus’, in which a trace of self-censorship can be discerned, the gesture is described with a light touch. The final phrases of the passage, that wet kiss between breast and penis, are what makes the description intensely erotic for some and horribly obscene for others.

Bettina Rheims, Anna Karina, 1988

Within the logic of the novel considered in its totality, this kiss testifies to the fact that Connie has finally reconciled herself with life and love, and accepts her desiring dependence on the male organ. It is in fact a gesture of allegiance about which one may have divergent opinions, depending on whether one adopts a feminist vision or Lawrence’s romantic and phallocentric one. Constance next even consents to be sodomized and to tolerate with indulgence, even complacency, Mellors’ speaking ecstatically about her behind: She would have thought a woman would have died of shame. Instead of which, the shame died. Shame, which is fear: the deep organic shame, the old, old physical fear which crouches in the bodily roots of us and can only be chased away by the sensual fire, at last it was roused up and routed by the phallic hunt of the man, and she came to the very heart of the jungle of herself. She felt, now, she had come to the real bedrock of her nature, and was essentially shameless. She thus reverts, step by step, to a state of nature and loses all modesty as she progressively discovers sensuality.

Michael Thompson, Julianne Moore, 2000

This, then, was Lawrence’s aim: Constance reconciled with her primitive sensuality. The appreciation of such a passage and of the logic that led to it cannot be taken for granted. Indeed, if one subscribes to the sensualist theory that Lawrence promotes via Connie, his spokeswoman (and this presumes a certain combination of the factors mentioned earlier that impinge upon one’s judgement), this passage can be construed as a hymn to life. If not, it is simply a rationalization of a perversion based on a cheap philosophy.

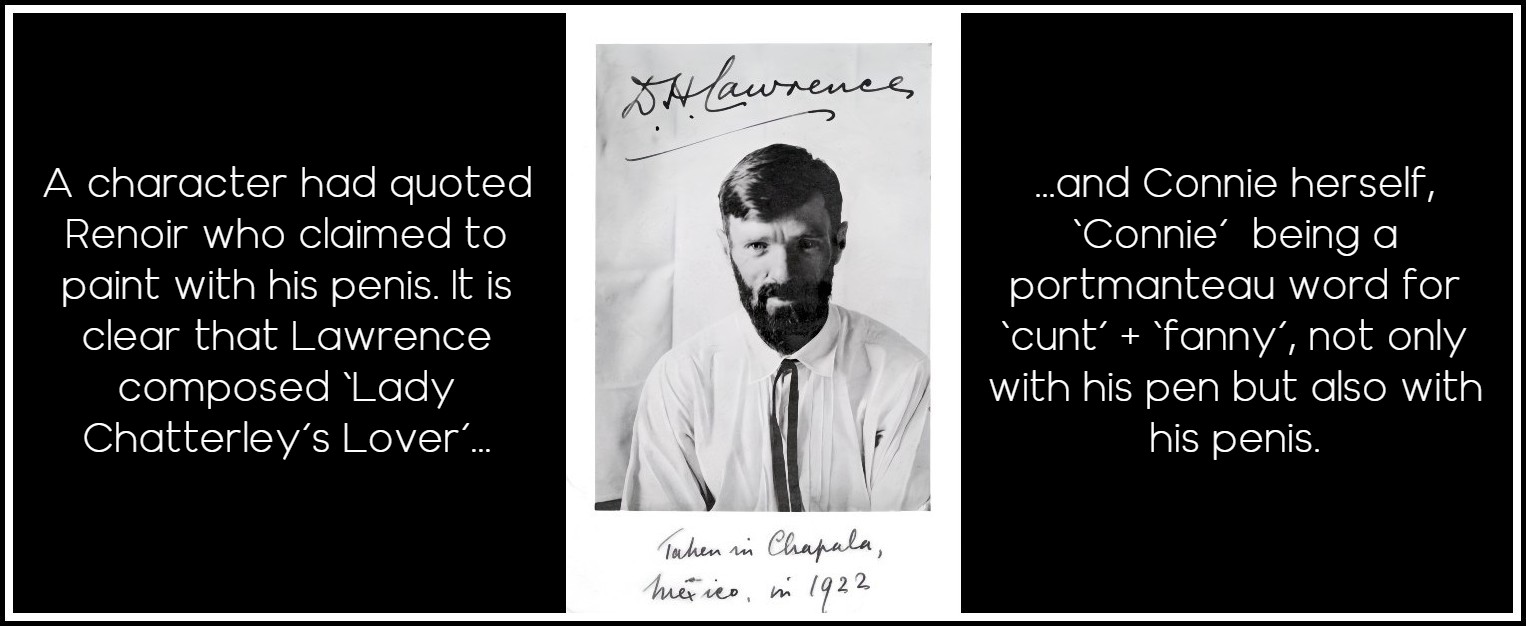

Photo: Craig McDean

In both cases, it is with reference to the author and not the text that the judgement is determined: a thesis is articulated, the reader is free to accept or reject it. That thesis is not that of the reflector character but of the author himself. Indeed, throughout the novel, we see that Lawrence has meticulously fashioned an object that perfectly corresponds to his desires: a submissive woman who pledges allegiance to the phallus, or simply to his penis, and who nevertheless considers herself totally fulfilled. It is not Mellors who harvests the fruit of Connie’s evolution but, phantasmatically, the author himself. Mellors is no longer a character in his own right but the phallus in all its majesty. The last lines of his letter, at the end of the novel, read like a confession of the creator to his creature, John Thomas (the name by which Lawrence designates Mellors’ penis): John Thomas says goodnight to Lady Jane, a little droopingly, but with a hopeful heart. We recall that, earlier, a character had quoted Renoir, who claimed to paint with his penis. It is clear that Lawrence composed Lady Chatterley’s Lover and Connie herself—’Connie’ being a portmanteau word: ‘cunt’ + ‘fanny’—not only with his pen but also with his penis.

D.H. Lawrence, Mexico, 1922

Lawrence did not manage to remove himself from Lady Chatterley’s Lover, as he did with some success in his masterpiece, Women in Love. Time and again his novel betrays his frustrations and his phantasies as he obsessively develops his sexual thesis. It is an author’s discourse, not a poetic text, even if certain passages, as we’ve seen, do have an aesthetic dimension. We now have a better understanding of why it is so important for an author to efface himself behind a distant authorial figure, to show rather than to tell (as the post-Jamesian formula puts it). Indeed, the reader with poetic expectations, however slight, is wiling to involve himself as a desiring being in his reading of the text, but he refuses to find himself confronted with the author’s unfiltered phantasies: the pleasure of the text has to be a personally constructed one, and not a mere identification game.

D.H. Lawrence, Passport Photo

MAURICE COUTURIER: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments