ART & AUDIENCE II: LEONARD COHEN

LEONARD COHEN, OR LIVING PRESENCE VERSUS DEATHLY CONSUMERISM

What accounts for Leonard Cohen, on his last tour, encountering an audience ‘on the other side of intimacy’, one much larger than ever before?

Richard Jonathan

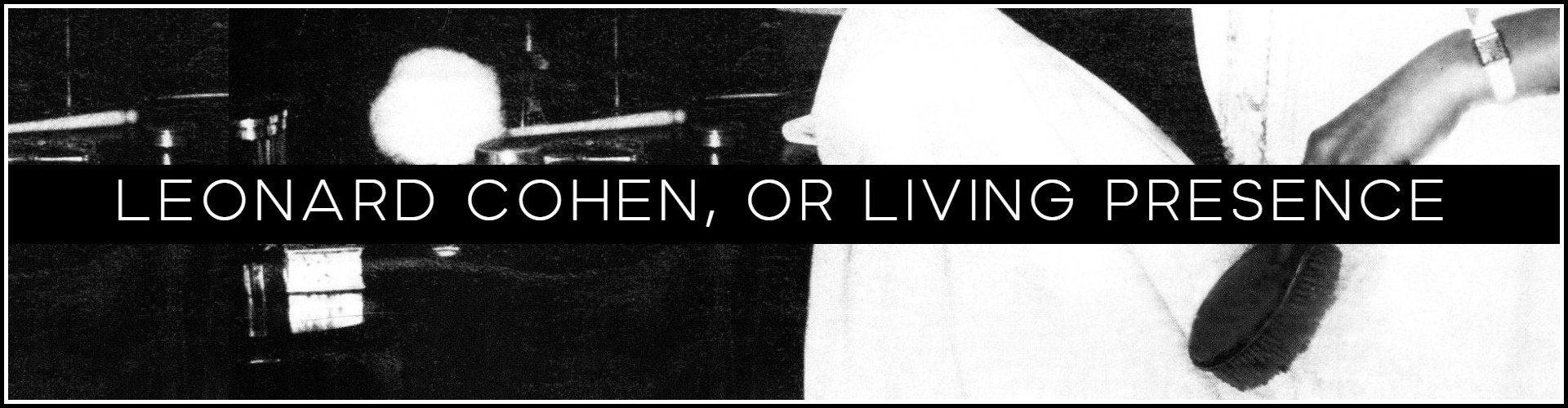

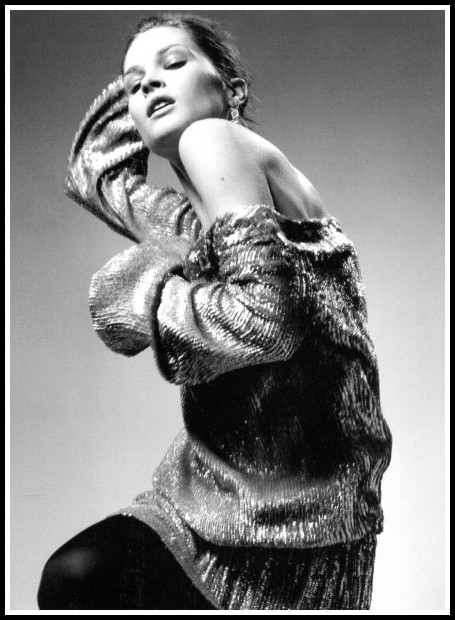

Jerry Hall | Rico Puhlmann, Harper’s Bazaar, 1975

I – LEONARD COHEN: ENCOUNTERS & GESTURES THAT WEREN’T POSSIBLE BEFORE

A summer’s evening, Toulouse, 2009. I’m standing, touched and contemplative, on the parvis of the Zénith, a 9,000-seat concert hall. A woman approaches and extends her hand. ‘Justine’, she says; ‘Richard’, I reply. Silvery lamplight flickers in her misty blue eyes; in the pressure of her touch, past and future dissolve. She offers me a cigarette; I don’t smoke, but take it and enter the flame. Wistful, a smile inaugurates the silence that ensues. Intimate fingers, distant eyes; the black curve of a flat sandal, the suspension of blonde in the breeze. When I stamp the glow from my cigarette butt, neither of us add any words to the few that have passed between us. When we re-enter the hall, we shake hands as firmly as before, then go our separate ways.

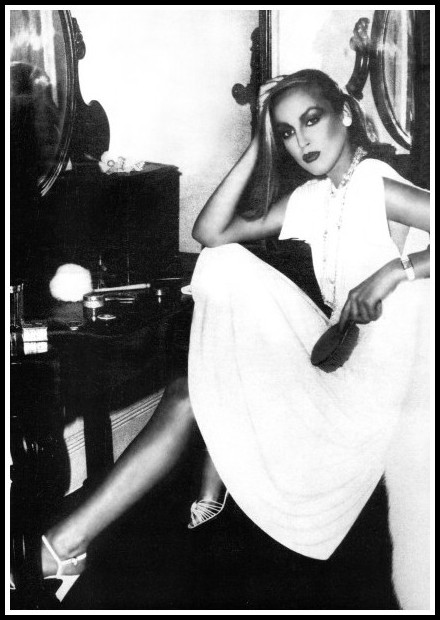

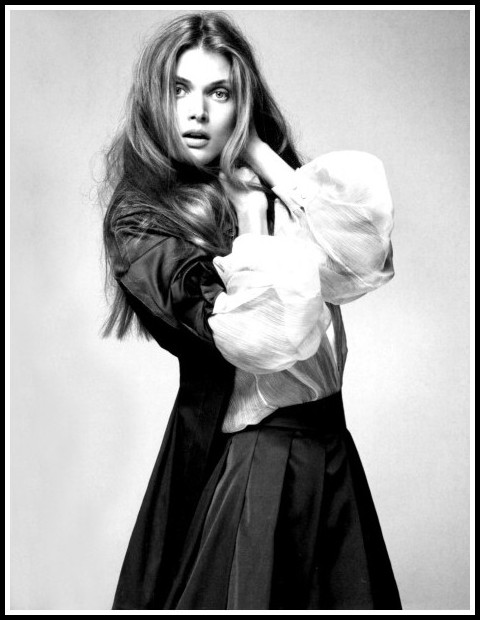

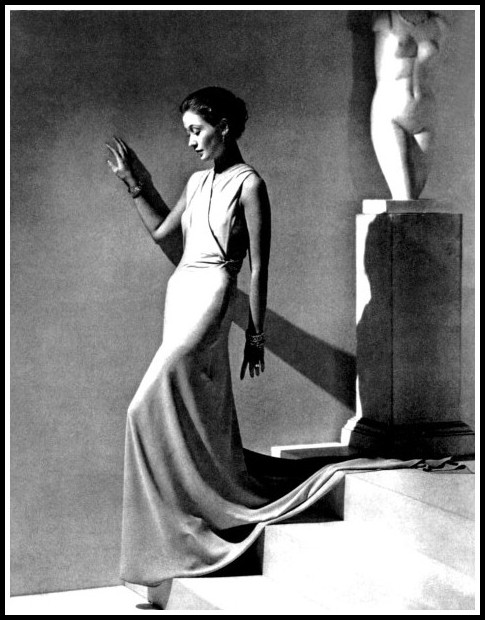

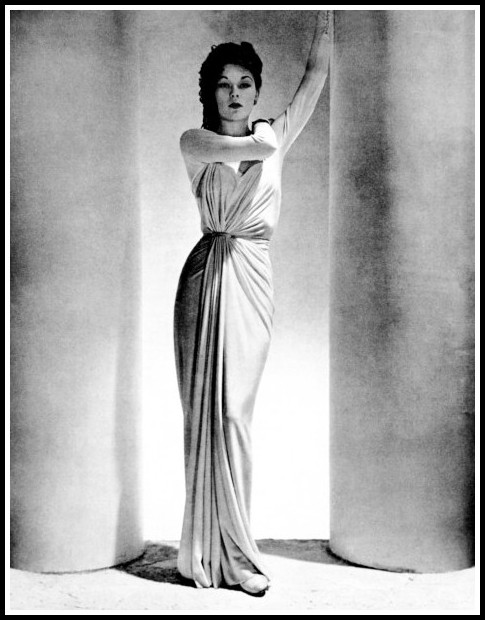

Wenda Parkinson | Clifford Coffin, Vogue, 1947

What is it about Leonard Cohen that makes such an encounter possible? That replaces small talk with silence, that makes presence palpable?

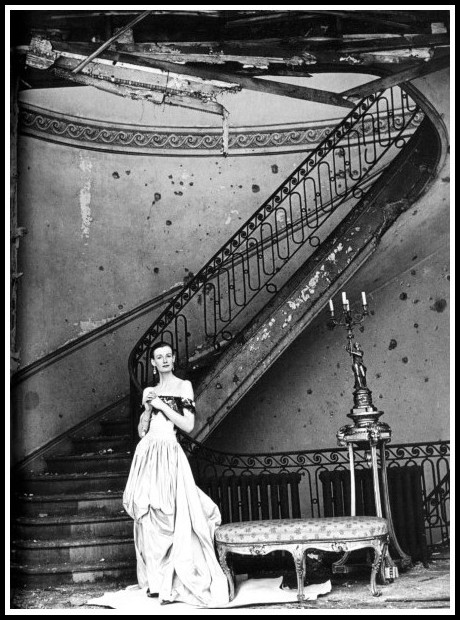

Della Oake | Norman Parkinson, Vogue, 1951

A winter’s evening, Toronto, 1985. I’m sitting, a sullen girl beside me, in a balcony seat in Massey Hall. ‘Dignity’, I say to myself, observing the man in a dark suit on the stage below, plucking notes from an acoustic guitar. An aura of the sacramental; sacred fire, vestal virgins. Though it be but the start of the concert, at the end of the song the girl whispers through the applause, ‘I’m glad I came’, and sticks her tongue in my ear.

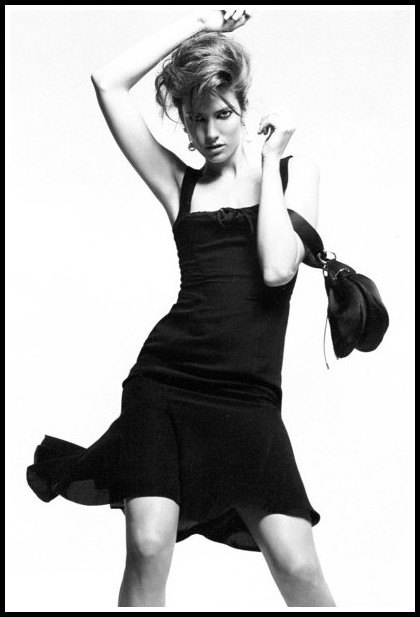

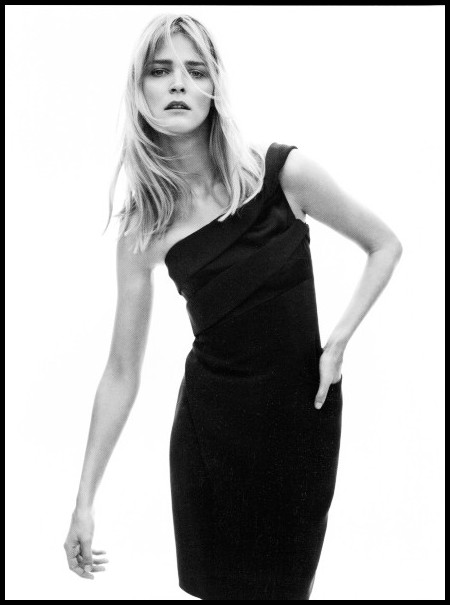

Erin Wasson | Robert Wyatt, Vogue, 2003

What is it about Leonard Cohen that makes such a gesture possible? That replaces sullenness with joy, pettiness with grandeur?

Malgosia Bela | Lachlan Bailey, Vogue, 2008

II – LEONARD COHEN: THE SIDE OF SNAKE EYES TOSSED AGAINST THE SIDE OF SEVEN

‘Dance Me to the End of Love’, ‘Hallelujah’ and ‘If it Be Your Will’ drew in multitudes on Leonard Cohen’s final tour (2008-2010). The songs first appeared on the Various Positions album of 1984, an album Columbia refused to release in the USA. Why? Cohen’s albums had always sold poorly in the States, and Columbia saw no reason why Various Positions, coming on the back of the lacklustre sales of Recent Songs (one of the most ravishingly beautiful albums of all time), would capture an audience big enough to make an American release profitable. In Europe, in contrast, the artist had a bigger audience, making a release there worthwhile. During that final tour, Cohen thanked his European audiences for ‘keeping the songs alive’ during the long years of indifference to his music in the USA. So, art and audience: I will take up my theme by considering the differential reception of Leonard Cohen’s work in Europe and America.

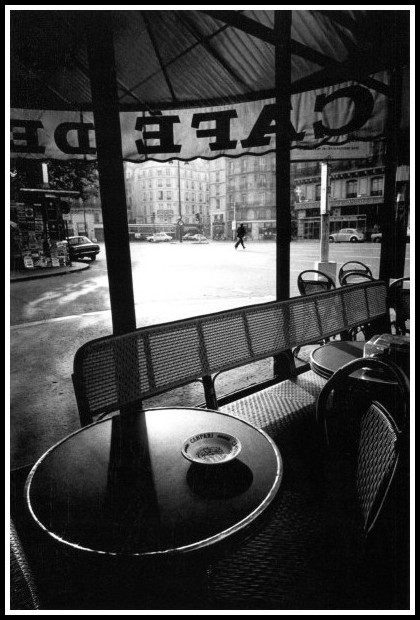

Jeanloup Sieff, Café de Flore, Early Morning, 1975

We live in an age of hyperconsumerism, with the digital body snatchers (DBS) turning countless individuals into 24/7 consumption zombies. The DBS feed on the blood of information, relentlessly codifying and monetizing it as they coax individuals to sacrifice their singularity on the altar of perpetual consumption.

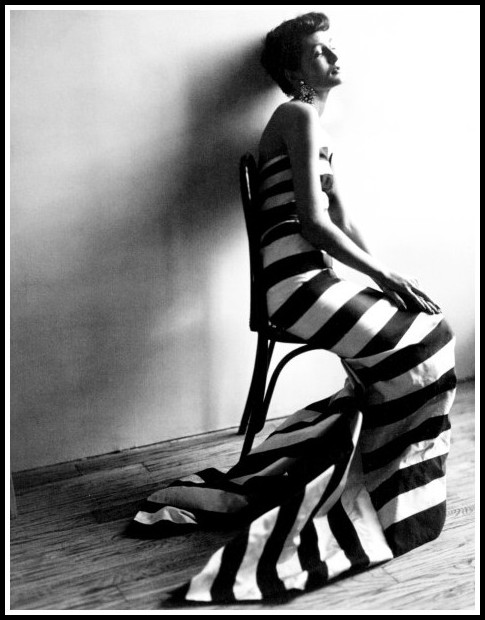

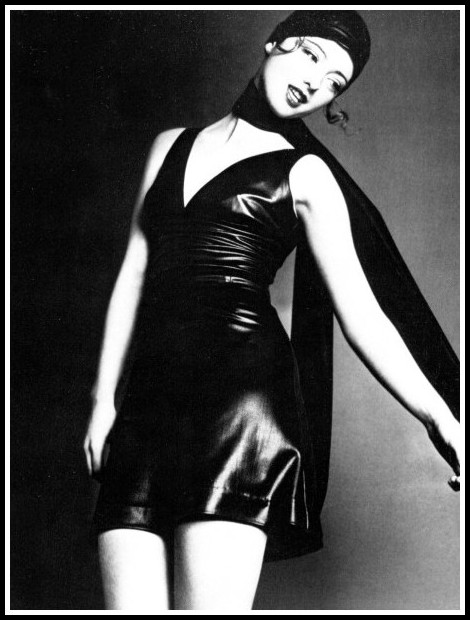

Helmut Newton, Vogue, 1966

The impact of this on the individual is profound; I’ll cite but three examples. First, time becomes inert, loses its natural rhythms, its lived duration and humanizing depth. In their place is one ever-on ‘now’, awaiting the next click or tap to commoditize another ‘need’ or monetize more information. Second, personal and social identity become shaped in a virtual world, flattening out the individual by deadening his or her vitalizing difference. Third, the individual who buys into the DBS system accepts its underlying assumption: that what cannot be codified and monetized is not worthy of attention. And thus the mystery at the heart of his or her humanity—the domain where ethics are forged in the encounter with otherness, where the chaos of a life is turned into a cosmos—becomes a no-go zone. The invasion of the body snatchers, digital technology in the service of hyperconsumerism, is well and truly underway.

Maxime de la Falaise | Cecil Beaton, Vogue, 1950

If Leonard Cohen has been consistently popular in Europe and only recently popular in America, and if, in 2008-2010, he played to much bigger audiences than ever before in both places, I will argue that this is because of the ravages wrecked by hyperconsumerism in the twenty-five years between Various Positions and the last tour. Indeed, at one decade into the 21st century, a decade in which the DBS had already penetrated vast tracts of our lives, people were suddenly receptive to a wandering artist from another era, a man whose only concern was precisely that which the DBS couldn’t touch: the mystery at the heart of our humanity. Let us consider a few examples.

George Hoyningen-Huene, Vogue, 1934

The cult of celebrity is an essential component of the hyperconsumerist machine. Leonard Cohen always refused celebrity. He refused to make himself a vehicle for selling a vacuous dream. To the mantra of social media—build my brand, feed my fame; make me money, play the game—he opposed the humility of ‘I’m just paying my rent every day in the Tower of Song’.

Wenda Parkinson | Norman Parkinson, Vogue, 1951

The cult of happiness is also essential to the hyperconsumerist machine. Leonard Cohen never pedalled happiness. Opening his set at the Isle of Wight concert in 1970, for example, before asking the audience to light a match so that he could see where they were in the darkness, he said, ‘I don’t want to impose on you, this isn’t like a sing-along-with-Mitch’, making it clear that the fellowship he sought was an encounter of individualities, open and free, and not a simulacrum of togetherness as in a Coca-Cola commercial.

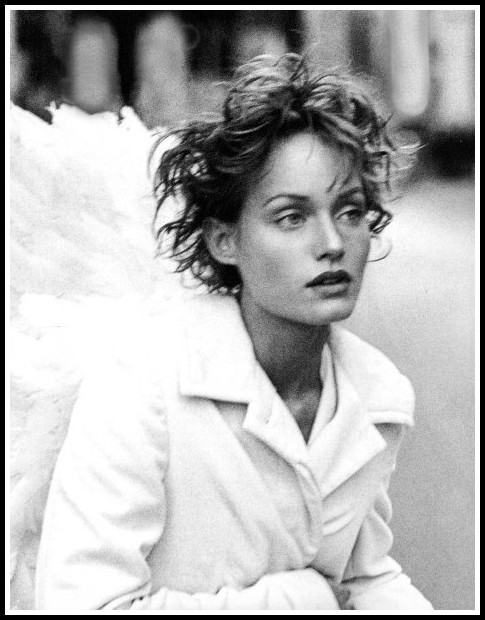

Amber Valletta | Peter Lindbergh, Harper’s Bazaar, 1993

Hyperconsumerism is a machine for trivializing reality. How does it do this? The ways are many. Here’s one: it debases and impoverishes language. ‘Like’ and ‘friend’ are but the tip of the iceberg; deeper down is the whole discourse, pitched in tones of familiarity (‘howdy’, ‘oops’, ‘stuff’), that presumes everyone has always already bought in to the ideology (‘to have’ over ‘to be’, social activity as a front for self-interest, the masses as the arbiters of taste, the colonization of individual experience, etc.). To choose one’s own words, to find one’s own rhythms, is a step towards assuming personal responsibility: to reduce one’s language to the textures of electronic life is to abdicate it.

Greg Kadel, Vogue, 2002

So, I am suggesting, one reason Leonard Cohen’s audience expanded so unexpectedly was because he restored to language its richness and spoke in an individual voice: qualities that help one resist the DBS. He refused to trivialize reality, yet his seriousness did not preclude humour; to the shorthand of cliché, he preferred fresh metaphor. He proffered no slogans, no solutions, no self-satisfied wisdom: he only offered the music and lyrics he had fashioned from his ‘education in the world’.

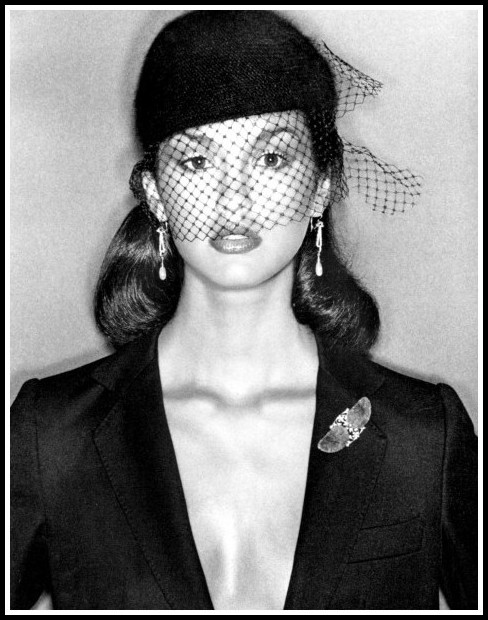

Jeanloup Sieff, Portrait with Veil, 1985

Hyperconsumerism accelerates the process of consumption. To the instant gratification promised by the DBS, Leonard Cohen opposed the slowness of meditation; to the cult of FOMO and winning, he opposed retreat and the spirit of losing (‘I’m on the side of snake eyes tossed against the side of seven’). Against the accelerating rollout of novelty, he chose faithfulness and tradition (‘Old Ideas’); against consumer gregariousness, he chose the solitude of the mystic: ‘When wind and hawk encounter, what remains to keep?’. And, when he could not withdraw, he nevertheless cultivated his secret life: ‘I bite my lip, I buy what I’m told / from the latest hit to the wisdom of old / But I’m always alone and my heart is like ice / and it’s crowded and cold in my secret life’.

Lud (Ludmila Feodoseyevna) | Horst, Vogue, 1938

For the many thousands who came to listen to Leonard Cohen on his last tour, was not his stillness at the centre of the turning wheel a disavowal of the merry-go-round of consumerism? Was not the living presence of his being a reminder of the deathly vacuity of having?

Josh Olins, Vogue, 2010

III – LEONARD COHEN: AN INVITATION TO A RICHER EXPERIENCE OF BEING

Why is it that Leonard Cohen’s art has always found a more receptive audience in Europe than in America? Is it because Europeans are less willing to substitute sensation (haste) for feeling (unhurriedness), triviality (surface) for seriousness (depth), simulacrum (prettiness) for the real thing (beauty)? In a word, is it because, thanks to their inner resources, Europeans have better resisted the onslaught of hyperconsumerism?

Guy Bourdin, Vogue, 1969

I think so. I think Leonard Cohen, in his acute awareness of the obscenity of success, could never be absorbed into the culture of consumerism. The very notion of ‘the obscenity of success’ is beyond the ken of most Americans: Europeans have more of a clue. Be it the way Cohen allied pity and lucidity or mind and body, the way he honoured women or refused to wave a flag, in the maelstrom of consumerism he was inviolable. In this, then, he was un-American (cf. Bowie’s ‘Scream Like a Baby’: ‘Well I wouldn’t buy no merchandise’).

Janice Dickinson | Mike Reinhardt, Vogue, 1978

Note that ‘un-American’ is not ‘anti-American’. Cohen, after all, chose to live much of his life in the USA. No, by ‘America’ I mean ‘the country where the “sphere of commoditization” is greater than in any other country’. In other words, America is the land where citizens are the least critical of having an ever-widening range of their experience sucked into the ‘sphere of commoditization’, dissolved in the fetish of the dollar. In Europe, and in France in particular, this form of ‘Americanization’—‘consumer’ trumps ‘citizen’, ‘business’ overrides ‘person’, ‘amusement’ outweighs ‘art’—is seen as degrading to both individual and society. Indeed, for Europeans, ‘greasing the wheels of consumerism’ is not the wherefore and the why of citizenship, personhood and art.

Nena von Schlebrugger | Claude Virgin, Vogue, 1959

All art is subject to the ‘contingency of cultural visibility’ (Amy Hungerford, Making Literature Now), and in Leonard Cohen’s finding a large audience, fate served up contingency with a dollop of irony. Indeed, had his manager not stolen his money, prompting him to go on tour, Cohen, most likely, would have remained largely obscure. I imagine the poet relished the black humour of that. The dynamics of art and audience, here, worked out well: grace emerged from commerce, silence (the condition of music) from noise, and joy from despair. Just another night’s work for the poet on the road. Cheers, Leonard.

Eva Herzigova | Dominique Issermann, Vogue, 1995

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments

1 thought on “Leonard Cohen, or Living Presence”

“The cradle of the best and worst.” That’s what Cohen called the USA. Of course it was also his spiritual and musical home, if not his native home. I see your point about hyperconsumerism in the USA (be careful that you don’t include all of America in that analysis), but you miss seeing that he and his music originated in a culture layered with hyerconsumerism, but not submerged by it. Another great song artist who lives and works in the USA, Joni Mitchell, said this of Europe in another song: “It’s too old and cold and settled in its ways – but California!” It is hard to imagine a more consumerist culture than that of LA (there’s a tie in to your article on success here too) and Hollywood, yet they nourished such vital, counter-culture artists as Cohen and Mitchell.