LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – I

WILD HORSES | PISSING IN A RIVER

Mick Jagger—The Rolling Stones | Patti Smith—Patti Smith Group

Richard Jonathan

LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – THE FIRST PAIR

‘Wild Horses’ is a plea for a beloved to stay, ‘Pissing in a River’ for a beloved to come back. In the first, she is on the point of leaving; in the second, he has already left (or more precisely, the lover positions herself, for most of the song, as if he has already left).

WILD HORSES

Mick Jagger | Norman Seeff, 1972

‘Wild Horses’ echoes both the lyric poetry of courtly love and the confessional poetry of sixties America. The ‘graceless lady’ harks back to the troubadours’ ‘fair lady who ever says No’, while the high-flown fervour of ‘wild horses couldn’t drag me away’ evokes the knights of Arthurian romance. The man is the servant of the woman—‘the things you wanted I bought them for you’—and the theatricality of the romantic code is conjured in ‘sweeping exits’ and ‘offstage lines’.

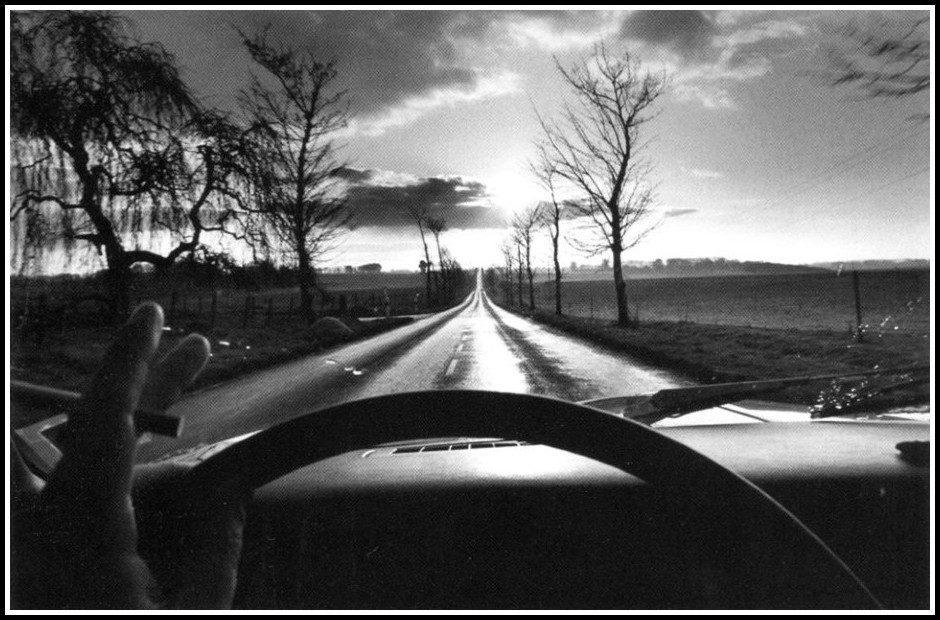

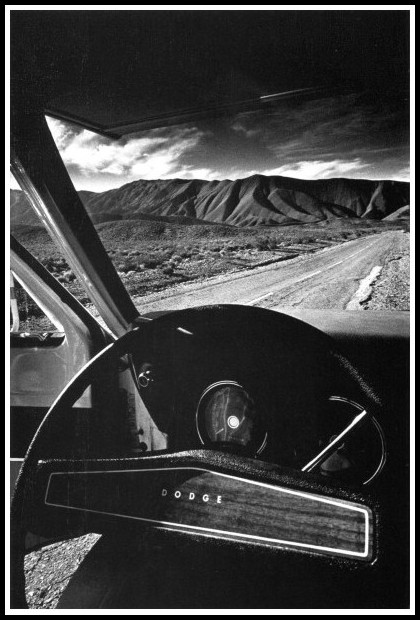

Jeanloup Sieff, On the Road, 1986

As for the confessional impulse, we see it in the difficulty of leaving ‘childhood living’. We also see it in the ‘dull aching pain’, the ‘sin and a lie’, the ‘faith has been broken’ and the ‘tears must be cried’, all alluding to the adult relationship that is dissolving. Despite all these difficulties, despite the beloved making him suffer (‘now you’ve decided to show me the same’), the lover remains steadfast in his love, declaring that no parting theatrics ‘could make me feel bitter or treat you unkind’ and ‘you know I can’t let you slide through my hands’. Moreover, he confirms his confidence by projecting the couple into a better future: ‘Let’s do some living after we’ve died’ and ‘wild horses, we’ll ride them some day’.

Jeanloup Sieff, Death Valley, 1972

The lover has his freedom, he adds, but doesn’t have much time: the moment is grave, the beloved is determined to leave. And so he harnesses himself to the wild horses of romance, marshalling a millennial tradition in a bid to make her stay. Indeed, he knows that ‘it is by the beauty of his musical homage that a poet wins his lady’ (Denis de Rougemont, Love in the Western World).

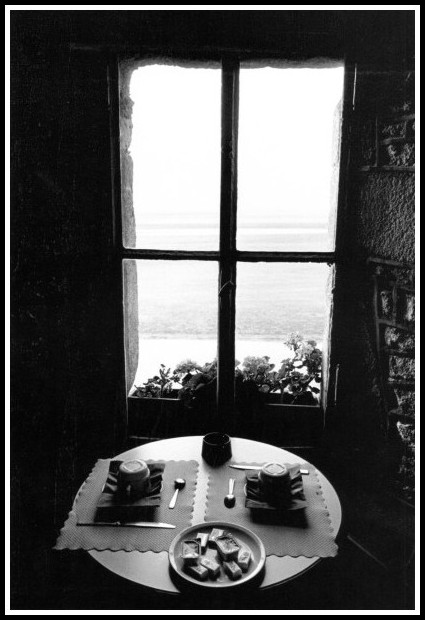

Jeanloup Sieff, Mont-Saint-Michel, 1989

In ‘Wild Horses’, the lyrics’ evocations of courtly love combine with the steely tenderness of the music to convey the lover’s plea very effectively: the song is touching in its depiction of the vicissitudes of separating.

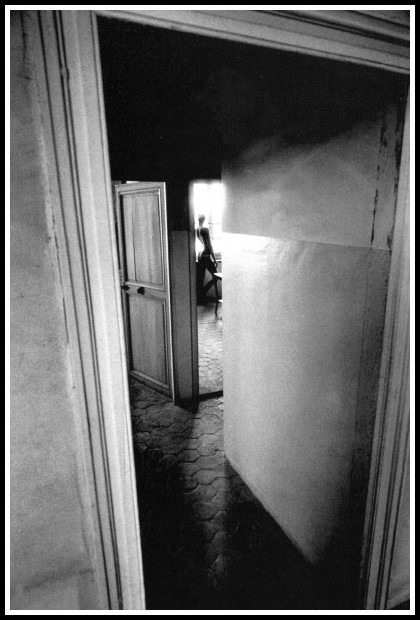

Jeanloup Sieff, Distant Nude, 1972

WILD HORSES

Mick Jagger — The Rolling Stones

Childhood living is easy to do

The things you wanted I bought them for you

Graceless lady you know who I am

You know I can’t let you slide through my hands

Wild horses couldn’t drag me away

Wild, wild horses couldn’t drag me away

I watched you suffer a dull aching pain

Now you’ve decided to show me the same

No sweeping exits or offstage lines

Could make me feel bitter or treat you unkind

Wild horses couldn’t drag me away

Wild, wild horses couldn’t drag me away

I know I’ve dreamed you a sin and a lie

I have my freedom but I don’t have much time

Faith has been broken tears must be cried

Let’s do some living after we’ve died

Wild horses couldn’t drag me away

Wild, wild horses we’ll ride them some day

Wild horses couldn’t drag me away

Wild, wild horses we’ll ride them some day

PISSING IN A RIVER

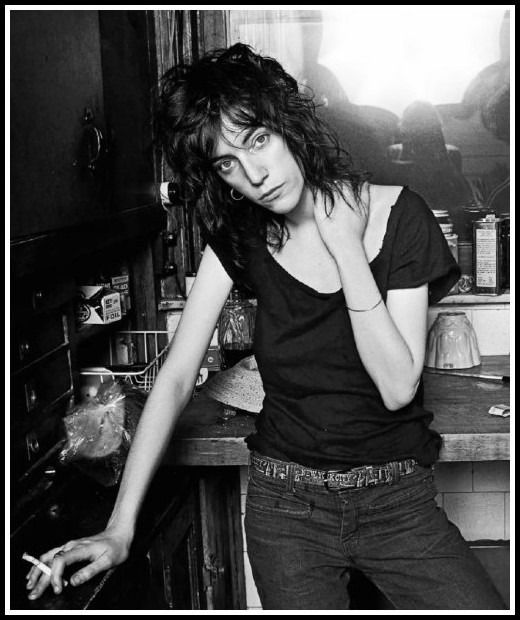

Patti Smith | Norman Seeff, 1969

The conventions of Romance are a world away from the raw emotion of ‘Pissing in a River’. The song digs down deep into the body and the soul and comes up with a powerfully elemental plea. ‘Come, come, come, come back, come back, come back, come back, come back’: both command and supplication, the exhortation to the beloved is delivered plain. But the lover knows this is not enough, and so she resorts to magic. First, she becomes a shaman, from her fingers spirit emanates—‘tattoo fingers shy away from me’ (a tattoo is a permanent prayer, a symbol of identification with the heavenly powers; ‘shy away’ suggests the hand is no longer at the mind’s command, that the spirit is at work)—while voices invoked ‘mesmerize’ and the sea becomes sonorous, ‘beckoning’. And then the lover becomes a witch, and like the second witch in Macbeth with her ‘eye of newt and toe of frog / wool of bat and tongue of dog’, she utters an incantation: ‘spoke of a wheel, tip of a spoon / mouth of a cave, I’m a slave I’m free’ (the spoke of a wheel connects the centre and the circumference, heaven and earth, while the cave gives access to the underworld).

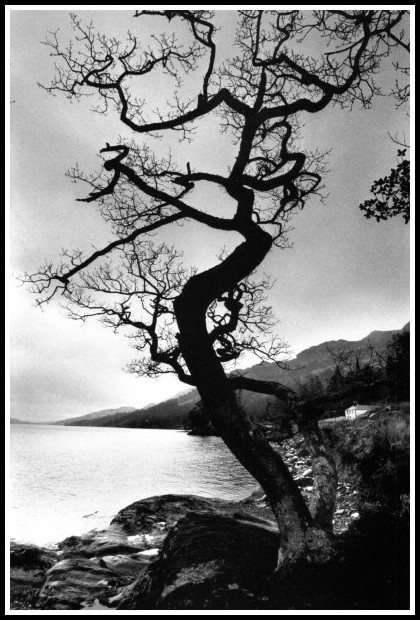

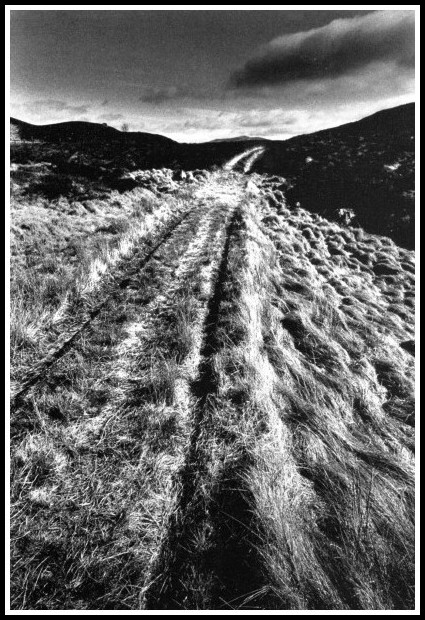

Jeanloup Sieff, Scotland, 1972

When shaman and witch fail to bring the beloved back, the lover adopts a strategy of abjection: piss—‘pissing in a river’—and shit—‘my bowels are empty, excreting your soul’ (which also indicates exorcism). The music makes the abject sublime, but even sublime abjection can’t bring the beloved back. And so the lover postulates self-abasement, but hangs on to her dignity: ‘Should I pursue a path so twisted? Should I crawl defeated and gifted? Should I go the length of a river, the royal, the throne, the cry me a river?’. She’s a slave to her obsession, she can crawl defeated, but she never forgets she’s free and gifted: the river is a river of tears, but also a royal road, a river of grace.

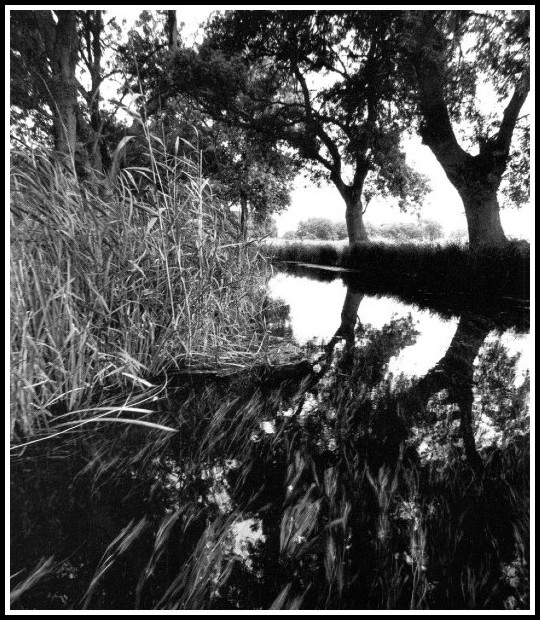

Jeanloup Sieff, The River Anapo (Sicily), 1983

That strategy, too, fails to bring the beloved back, and so the lover appeals to their past: ‘Everything I’ve done, I’ve done for you / Every move I made I moved to you’. She admits her helplessness—‘What more can I give you? Baby I don’t know’—and her desperation: ‘Oh I give my life for you’. To no avail. Finally, she reverts to plain assertion and supplication: ‘What about it? You’re gonna leave me. What about it? You don’t need me. What about it? I can’t live without you. What about it? I never doubted you’.

Jeanloup Sieff, All Roads Lead to Inverness, 1972

At the beginning of the song, one might have imagined the lover standing as she pisses in a river; at the end, I, for one, can only imagine her squatting: her charms overthrown, her cries bootless, she is the rejected lover whose defiant pride still burns—ecstatic above the abyss—but is tempered by humility. The beloved is gone. The lover cannot make him come back. Cry me a river.

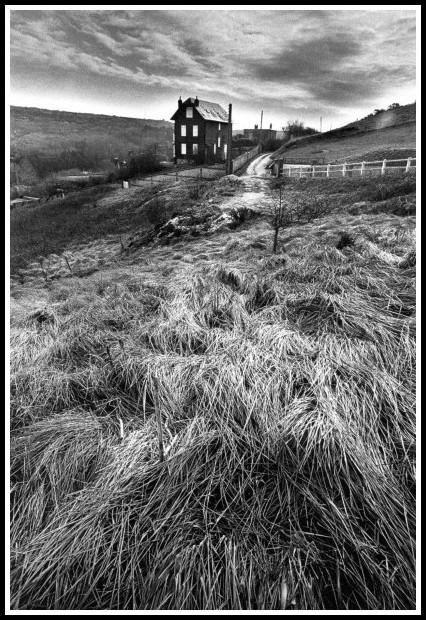

Jeanloup Sieff, Lefeu’s House (Petites-Dalles), 1980

PISSING IN A RIVER

Patti Smith—Patti Smith Group

Pissing in a river, watching it rise

Tattoo fingers shy away from me

Voices voices mesmerize

Voices voices beckoning sea

Come come come come back come back

Come back come back come back

Spoke of a wheel, tip of a spoon

Mouth of a cave, I’m a slave I’m free

When are you coming ? Hope you come soon

Fingers, fingers encircling thee

Come (back) come (take me back) come come come come (back)

Come (take me back) come come come come come

My bowels are empty, excreting your soul

What more can I give you ? Baby I don’t know

What more can I give you to make this thing grow?

Don’t turn your back now, I’m talking to you

Should I pursue a path so twisted?

Should I crawl defeated and gifted?

Should I go the length of a river?

The royal, the throne, the cry me a river?

Everything I’ve done, I’ve done for you

Oh I give my life for you

Every move I made I moved to you

And I came like a magnet for you now

What about it, you’re gonna leave me

What about it, you don’t need me

What about it, I can’t live without you

What about it, I never doubted you

What about it ? What about it ?

What about it ? What about it ?

Should I pursue a path so twisted?

Should I crawl defeated and gifted?

Should I go the length of a river,

The royal, the throne, the cry me a river

What about it, what about it, what about it?

Oh, I’m pissing in a river

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments