Performing the Feminine in Alban Berg’s Opera

LULU’S FEMININE PERFORMANCE

Judith Lochhead

Posted by kind permission of Judith Lochhead, Professor of Music History & Theory, State University of New York at Stony Brook

From The Cambridge Companion to Berg, ed. Anthony Pople (Cambridge University Press, 1997) pp. 227-244

I. INTRODUCTION

Over the past fifty years, much critical attention has been devoted to the character of Lulu, the title figure of Berg’s opera Lulu. And over that time, critical understanding of the character has changed, the changes motivated by feminist and post-structuralist thought in Europe and the United States. In the first wave of post-war criticism in the 1950s and 1960s, Lulu is characterised as ‘the Universal Mistress we all desire to possess or emulate’ (Donald Mitchell), and as ‘the goddess, the power of nature, the dæmonic, which never wearies of seducing’ (George Perle). For one critic, Theodor Adorno, Lulu is not the central character of the opera: ‘It is not Lulu who is the self out of whose perspective the music comes, but rather Alwa, who loves her’. For Adorno, then, a male voice frames the musical perspective; and for Mitchell and Perle, Lulu herself is incapable of framing a musical perspective because, as a fantasy of male sexual desire, she is an object merely to be possessed (or emulated, if the listener happens to be a woman).

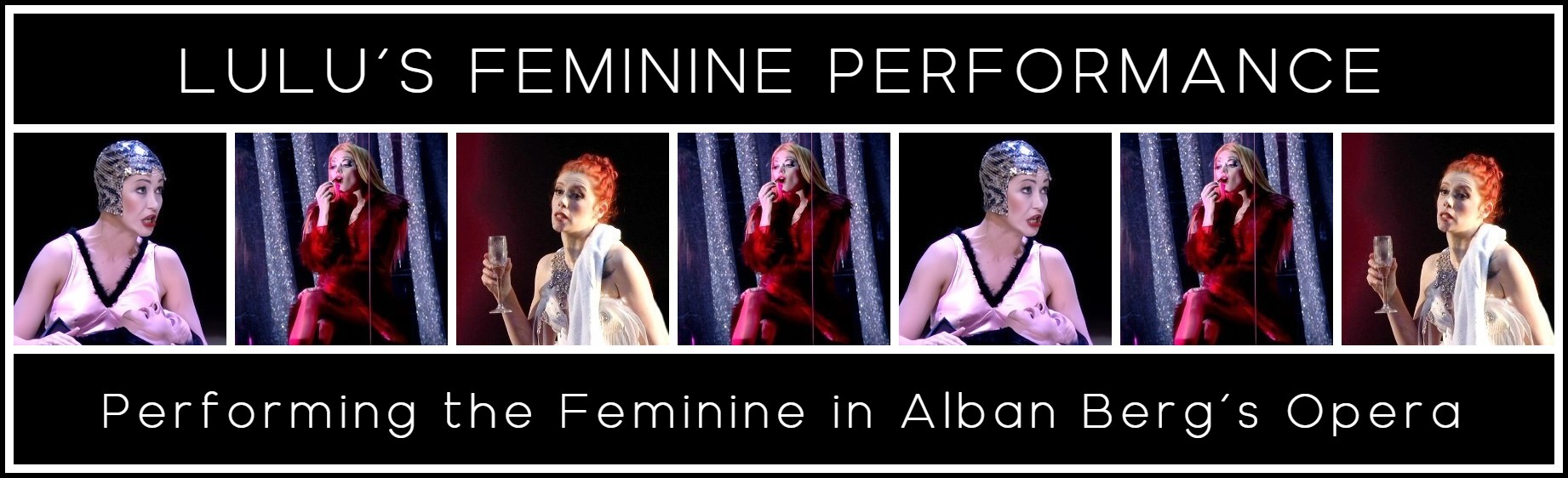

Four operatic Lulus: Marlis Petersen (Bayerische Staatsoper, 2015) | Laura Aikin (Zurich Opera, 2002) | Barbara Hannigan (La Monnaie-Bruxelles, 2012) | Patricia Petibon (Wiener Philharmoniker, 2010)

Yet, while depicting her as passive object in one breath, these critics describe her as a powerful and evil force in the next. As either passive object or natural force, Lulu has no agency. Furthermore, in describing Lulu as ‘Universal Mistress’ and ‘goddess’, critics draw upon transcendent meanings that effectively invalidate assessment of the type of character she presents. That is to say, since Lulu represents a universal type, the truth or meaning of the type is not an issue. In the second wave of critical writing in the 1980s and 1990s, the focus turns directly to the meaning of the Lulu character. For some authors, like Karen Pegley, the depiction of Lulu as a ‘femme fatale type’ plays a part in the ‘operatic tradition which perpetuates women’s oppression’. And for others, Lulu’s character is a ‘projection’ of male desire and fear which plays a role in the opera’s ‘social commentary’ by forcing us either to ‘reject the piece outright or face those aspects of ourselves to which we would rather not admit’.

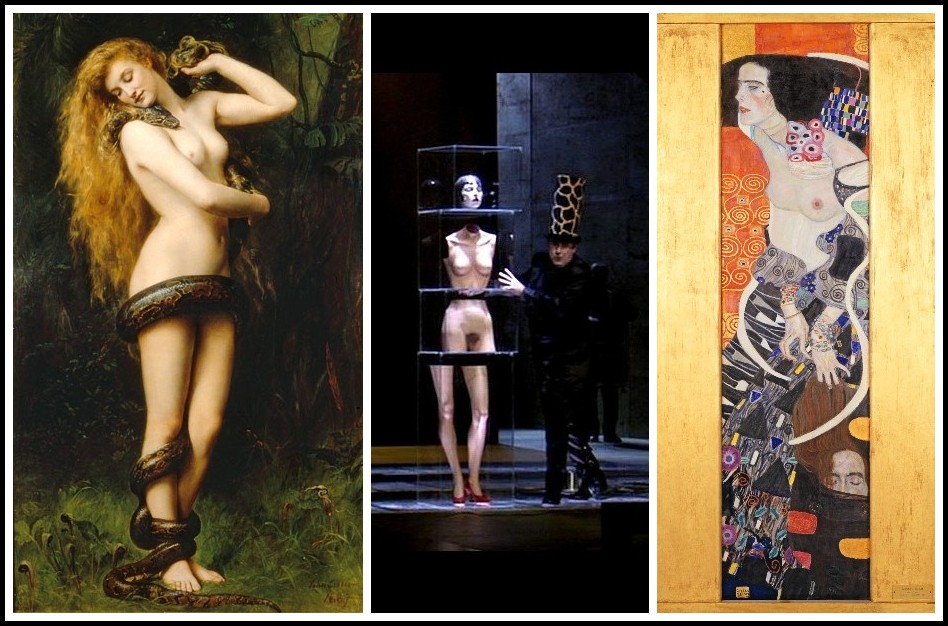

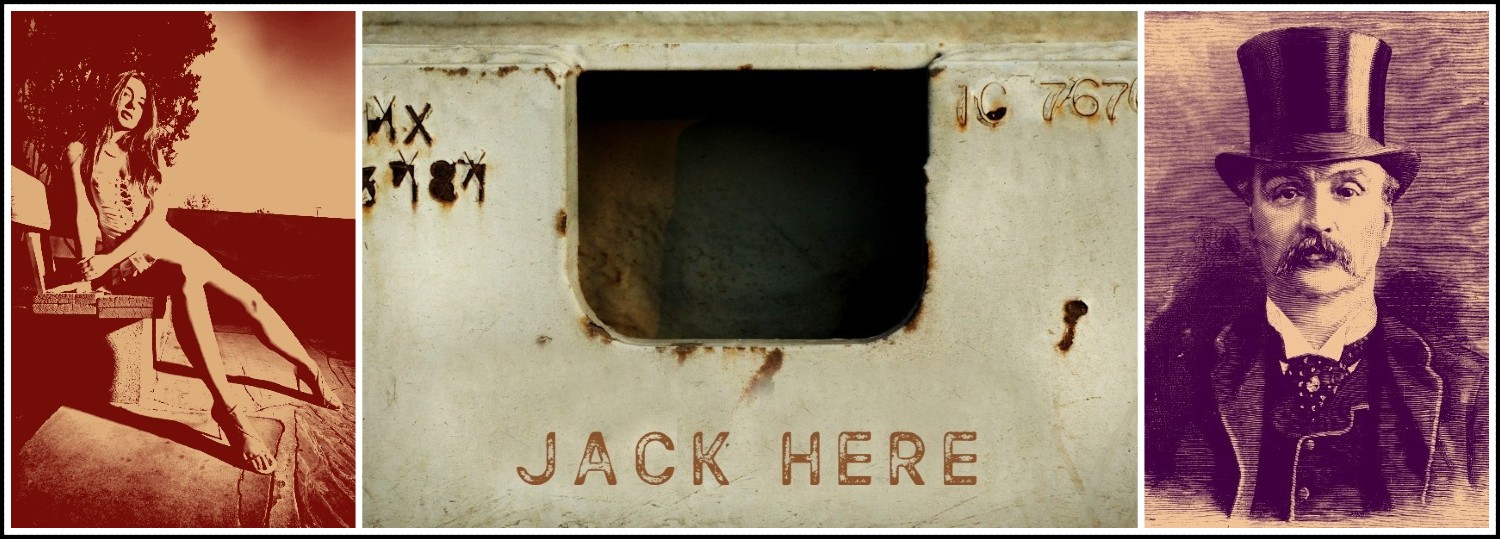

John Collier, Lilith, 1887 | Alban Berg, Lulu, Zurich Opera House, 2002 | Gustave Klimt, Judith II (Salome), 1909

For those who understand the opera as furthering ‘women’s oppression’, the Lulu character is ‘authentic’ in the sense that she directly embodies social attitudes toward women that have some general currency in the contemporary Western world. From this perspective, critics denounce the Lulu character (and the musical and dramatic forces that give rise to her) as a continuation of negative attitudes toward women. For those who understand the opera as ‘social commentary’, Lulu depicts characteristics that ‘signal’ negative attitudes toward women, but those characteristics are not embodied directly: that is, the Lulu character has no authenticity. Rather, the characterisation of her as a femme fatale, as a ‘dæmonic force of nature’, refers negatively to those features. From this vantage point, Lulu’s character does not embody any essential feature of ‘Woman’. Rather, the Lulu character depicts a social construction of ‘Woman’, a construction which plays out to tragic and destructive ends in the opera.

Hannah Hochs, Dada Dolls, 1916 | Man Ray, Portmanteau, 1920

The first wave of critics are united in viewing Lulu as an authentic character: she directly embodies the mythic and ambiguous features of ‘Woman’ that have typically circulated in Western cultures. The second wave of critics differ in their conception of the Lulu character. The conceptual framework of the late twentieth century yields an understanding of Lulu as both a perpetuation and a critique of negative attitudes towards women. The difference between these two understandings turns on whether the meaning of the character is read as authentic or parodic. If Lulu authentically embodies ‘Womanly’ features that have negative value in the culture, then the character is subject to criticism as a perpetuation of negative attitudes. If the Lulu character depicts those ‘Womanly’ features in order to criticise them, then Lulu is a parodic figure. The music of Lulu plays a central role in this critical scheme of authenticity and parody.

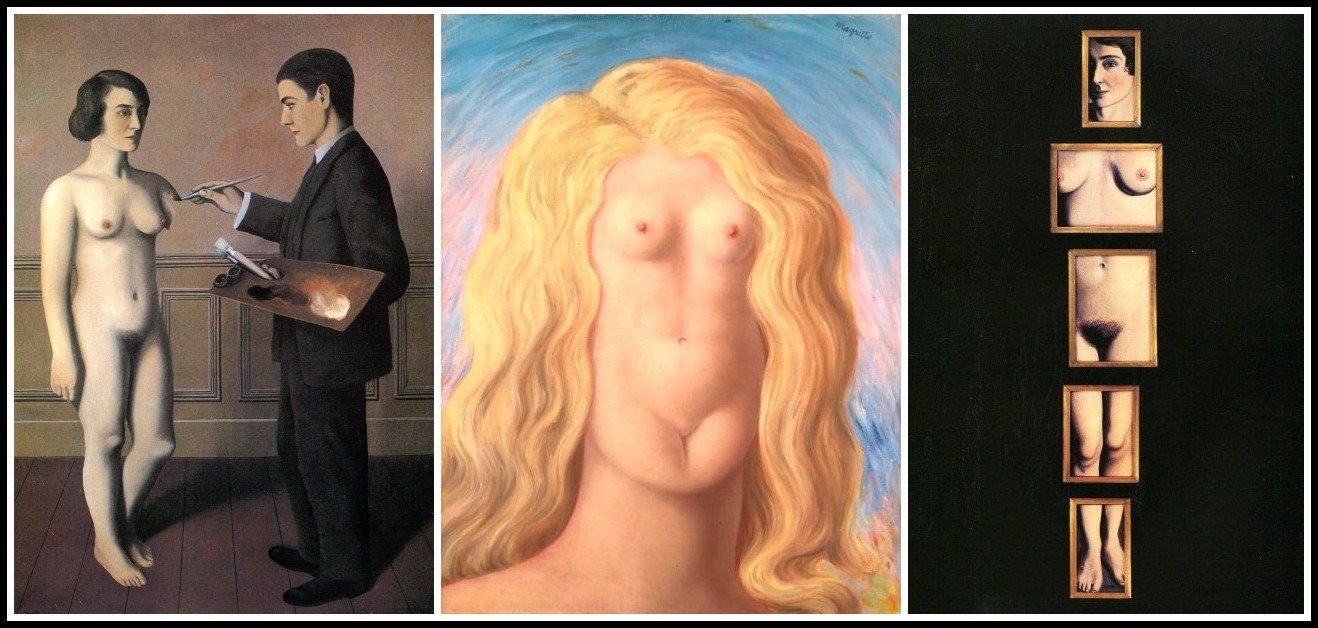

RENE MAGRITTE: La magie noire, 1935 | Philosophie dans le boudoir, 1966 | Les jours gigantesques, 1928

Both the first- and second-wave critics use two recurring musical passages in the opera as evidence for their understanding of the Lulu character. Donald Mitchell argues that one of these imbues ‘the operatic Lulu with profound and poignant feelings’ which are inconsistent with her passive and ‘decisively non-developing role’ in the drama generally. George Perle, arguing from the same observation of Lulu’s musically-projected feelings, understands the emotional content of the music as integral to a character who is essentially inconsistent: she is at once ‘the goddess which never wearies of seducing’ and the ‘human incarnation, the natural, and therefore, innocent woman’, the latter susceptible to emotional expression. Leo Treitler, writing in the 1980s, also refers to one of these two passages, calling it the ‘radiantly gorgeous music’ which ‘is a sign of Lulu’s identity’. Each of these three authors argues from the assumption of a music which authentically expresses human emotion or identity.

Jason Rosewell, Unsplash, 2016

But in most of the criticism over the last fifty years there is another kind of observation which implicitly—and only implicitly—contradicts the idea of an ‘authentic’ musical expression in the opera. It is a critical discomfort over the relation between musical sound and dramatic action: ‘what goes on in the orchestra pit and on the stage fail to match’ (Mitchell); ‘time after time in Lulu we become conscious of the disturbing difference between the emotional attitude adopted by the music and the nature of the text to which it is set’ (Douglas Jarman); and ‘if one is concentrating on action and character, the music seems completely inappropriate’ (Robin Holloway). The discomfort seems to arise from a sense of disjunction between music that evokes a world of emotional ‘beauty’, and dramatic action that—with its murders and suicides, prostitution, incest and deception—is decidedly not ‘beautiful’. While ‘irony’ and ‘pun’ provide some insight into this disjunction of sound and drama, the concepts of authenticity and parody surrounding critical understanding of the Lulu character provide a more powerful and comprehensive explanation.

Jason Rosewell, Unsplash, 2016 (glitched)

II. THE PERFORMANCE OF IDENTITY

Consideration of whether the Lulu character projects authentic or parodic attributes hinges on assumptions about personal identity and how it is constituted. Judith Butler’s book, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity analyses Western concepts of identity and provides a basis for understanding the assumptions that have driven critical accounts of Lulu. I shall frame my discussion of Lulu’s identity around her work, linking identity to issues of authenticity and parody. In particular, I shall use Butler’s ideas about the ‘performance of identity’ as the basis (i) for arguing that Lulu is a parodic character, and (ii) for demonstrating how the music of Lulu participates in projecting Lulu’s dramatic behaviour as a performance of the ‘feminine’. Two extracts from Butler’s book provide a starting point: (1) What grounds the presumption that identities are self-identical, persisting through time as the same, unified and internally coherent? (2) A great deal of feminist theory and literature has nevertheless assumed that there is a ‘doer’ behind the deed. Without an agent, it is argued, there can be no agency and hence no potential to initiate a transformation of relations of domination within society. The first, articulated as a question, suggests that the assumption of unity and coherence as a basis of identity is ungrounded, and illuminates the many, often contradictory facets of Lulu’s identity. The second raises the issue of agency in a social context; it provides a basis for considering whether the Lulu character is a ‘doer’ and whether she initiates a transformation in her social situation.

Alexander Grey, Unsplash, 2018 | Igor Omilaev, Unsplash, 2023

A theme of Lulu’s ‘non-unified and incoherent’ character runs through Wedekind’s plays and Berg’s opera. The primary difficulty in defining and even describing ‘who Lulu is’ has to do with the impossibility of tracing a single, continuous feature that defines her personality. Critics respond to her contradictory features in diverse ways. Donald Mitchell understands the contradictions as arising from the music and as a failure of Berg’s operatic conception. Some other critics respond by theorising different Lulus. George Perle argues that there are two: ‘a goddess, a power of nature’, and a human, ‘the natural, and therefore, innocent woman, who represents for all men the ideal fulfilment of sexual desire’. And Leo Treitler argues that there is a ‘counterpoint on the stage’ between Lulu as a ‘prodigy of nature’, as she calls herself, and ‘a Lulu character that is a complex of roles projected onto it by the men in the drama, out of their own needs, fantasies, and fears about Woman’. Critics theorising a ‘counterpoint’ of Lulus must also address the question of agency: is Lulu a ‘doer’ or is she simply a passive existent, ‘a power of nature’? And of the counterpointed Lulus, is there some primary or prior ‘identity’ which exists as a unified presence behind the other, ‘projected’ Lulus? In other words, is there an ‘authentic’ Lulu responsible for her actions?

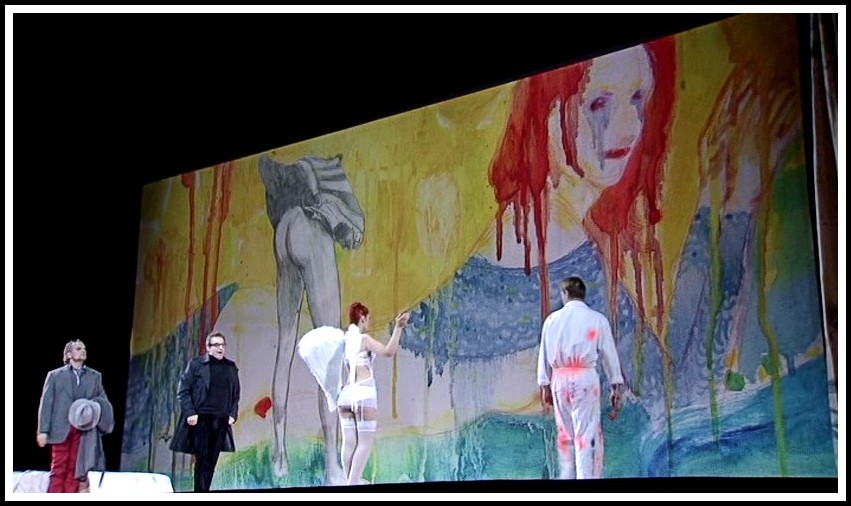

Alban Berg, Lulu, Bayerische Staatsoper, 2015

Both the issue of agency and the question of responsibility in conjunction with agency play a central role in the earliest criticism of the plays and the opera. Donald Mitchell, echoing the sentiments of Wedekind himself, interprets Lulu’s behaviour as being without agency: Lulu has ‘a decisively non-developing role, passive throughout’. But, Mitchell continues, she is deadly in her passivity: ‘She is akin to a straight-burning candle flame. The moths clatter their wings, singe themselves and burn themselves to death.’ In this formulation, Lulu’s destructive and fearful attributes affect the men around her, but these attributes gain their force not through her actions but through her being. While Mitchell considers Lulu ‘passive throughout’, he also uses language that implies action and personal will. By referring to her as the ‘murderer’ of Dr Schön, Mitchell ascribes an agency to her character that is at odds with his interpretation of her passivity. George Perle similarly considers Lulu ‘responsible’ for the deaths not only of Schön but also of the other men who die in the opera, referring to them as Lulu’s ‘victims’. For Perle, the possibility of ‘guilt’ is perhaps to be understood in terms of the human Lulu (rather than the goddess Lulu) that he theorises.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petibon (Lulu) & Michael Volle (Schön) | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The issue of agency arises quite differently for Leo Treitler. Coming to Lulu’s defence, he points out that the charge of ‘murder’ in the matter of Schön’s death is inappropriate: ‘A good lawyer would plead self-defence.’ If Lulu shot Schön in an act of ‘self-defence, of ‘self-preservation’, then we must assume that she had some ‘self’—some identity—to ‘preserve’. Treitler argues that this identity emerges most prominently in the music—in the sound—of the opera. One passage in particular is crucial: this music ‘is a sign of her identity. Through it she says “This is me”. It fills the air, as her presence fills the stage’. Writing about the same music, George Perle also finds evidence of a wilful subject. He asserts that in imbuing her with human agency the music ‘prepares us for Lulu’s heroic struggle against the Marquis’ (who attempts to sell her into prostitution).

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Alfred Muff (Schön) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

The problems critics encounter in attempting to offer understanding of the Lulu character – problems associated with her contradictory attributes, passivity and culpability—derive from underlying notions of identity. In particular, the idea of a unified personality and the idea of personal agency in conjunction with that personality pose significant obstacles to a satisfactory understanding of Lulu. While individual statements by individual critics help to illuminate the dramatic character of Lulu, questions still linger about whether there is some ‘authentic’ Lulu, some unified identity upon which the other Lulus are projected, about the relationship of these various Lulus to one another, and about the role the music plays in defining her various manifestations of character.

Three operatic Lulus: Laura Aikin, Barbara Hannigan, Patricia Petibon

Two additional extracts from Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble complete the basis of my approach to Lulu’s ‘feminine performance’: (3) The ‘coherence’ and ‘continuity’ of ‘the person’ are not logical or analytic features of personhood, but, rather, socially instituted and maintained norms of intelligibility. (4) There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its results. These extracts, like the two quoted above, form part of Butler’s discussion of the difficulties of defining and using the concept of gender in feminist theory. She argues that the difficulties arise from a ‘substantive’ notion of identity, that is, of the idea that identity is the unified and coherent ‘thing’ of personhood. Within prior feminist thought, stabilising features such as gender define the substance of identity, a substance which is fixed, unifying and persistent over time. In this conception, the stabilising attributes of identity such as gender are ‘essential’ traits, immutable properties of the person. The substantive notion of identity and its attendant ‘essentialism’ make personal agency problematic. If defined by a few stabilising and unifying features that persist through time (e.g., gender), then identity is not a matter of choice: identity is ‘being’ not ‘doing. The essentialism of the substantive notion of identity is closely linked with the idea of determinism.

Norbu Gyachung, Unsplash, 2021 | Marek Studzinski, Unsplash, 2024 | Edward Howell, Unsplash, 2020

Butler argues against the substantive notion of identity precisely because it leads into essentialist notions of gender and makes the idea of agency problematic. Instead, as extracts (3) and (4) suggest, Butler understands identity as a performative result that has no originary, defining source. Performative choices that individuals make and that result in ‘identity’ arise from ‘socially instituted and maintained norms of intelligibility’. In other words, performative choice—‘free-will’, agency—is motivated by the needs of an individual within a social context. Butler’s concept of performative choice opens some doors to an understanding of the Lulu character. First, Lulu can be conceived as the bundle of all her contradictory attributes, since the notion of a ‘performed’ identity can encompass a multiplicity of personality features. Such a conception eliminates the need for a ‘contrapuntal’ definition of Lulu’s identity but at the same time raises two questions about motivation. First, what would motivate a character to perform an identity of contradictory attributes? And second, if performative choices arise from ‘socially instituted and maintained norms of intelligibility’ why does Lulu choose to perform an identity that stretches the bounds of such intelligibility?

Alban Berg, Lulu, Michael Volle, Thomas Piffka, Patricia Petibon, Pavol Breslik | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

Lulu takes on the role of performer explicitly in her work as a dancer in Act I scene 3, but we may understand her actions throughout the entire opera as implicit performances. Lulu plays the coquette for the Painter in a flirtatious game of chase (Act I scene 1) as a means of responding not only to his but also to her own sexual desires. Her refusal to dance for Schön’s fiancée in Act I scene 3 is a performance intended to unmask Schön’s duplicitous behaviour toward her. In Act II, she entertains the Acrobat, the Schoolboy and Schigolch as demonstrations of her own ‘feminine’ prowess. And in Act III scene 1 she attempts to convince the Marquis not to sell her into prostitution with a bourgeois and melodramatic argument about honesty to one’s self. In this case, the performance has no effect on the Marquis, and he persists in his own scheme for ‘self’. Throughout, Lulu is motivated by both a ‘preservation of self’ and the rules of bourgeois society—by the rules of ‘social intelligibility’. She performs a ‘feminine’ role in an effort to gain social status, economic stability, sexual pleasure, family stability and in many instances, she performs for the sheer pleasure of performing. But there is a sense in which her performances are too successful, at least in Acts I and II. The performances are exaggerated, the ‘femininity’ too pronounced: in other words, the performances stretch the boundaries of intelligibility.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Pavlo Hunka (Schigolch) & Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

Part of Butler’s project in Gender Trouble is to demonstrate not only that gender and identity are performative choices but also that they are revealed as such by ‘the cultural emergence of those “incoherent” or “discontinuous” gendered beings who appear to be persons but who fail to conform to the gendered norms of cultural intelligibility by which persons are defined’. Butler is referring to such cultural practices as ‘drag, cross-dressing, and the sexual stylization of butch/femme identities’ which parody the socially intelligible gender types—man and woman, masculine and feminine. In other words, these cultural practices reveal gender as performative choice by subverting the comprehensibility of the socially accepted categories of ‘gendered norms’. An extension of Butler’s notion of gender parody can illuminate the problematic aspects of the Lulu character. Much of Lulu’s dramatic behaviour may be understood as her ‘performance of identity’. It is a performance which exaggerates attributes marked as ‘feminine’: this overabundant femme fatale changes her mood too abruptly, her sexually charged seductions are too overt, her allegiance to a moral self too melodramatic. The exaggerations effectively undermine not only the gendered role in which women typically gain their intelligibility but also any sense of Lulu as an ‘authentic’ character.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) & Natascha Petrinsky (Geschwitz) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

The behaviours of the men in the opera similarly parody the masculine response to the femme fatale type. They are mesmerised by her bodily appearance too easily, they give in to her seductions too readily. Geschwitz, Lulu’s lesbian lover, also falls under the spell of Lulu’s ‘femininity’, ‘performing’ her own exaggeration of selfless, all-sacrificing love. The parody of the ‘feminine’ and of the masculine and lesbian behaviours it animates has the effect of revealing the ‘feminine’ as performance and of subverting it as an ‘intelligible’ cultural practice. The playwright Frank Wedekind, as author of the Lulu plays, constructed a parodic character that itself performs the idea of the ‘feminine’ as performance. His character does more than simply parody the ‘feminine’, however. Through the fate of Lulu, Wedekind comments on the destructive consequences of the ‘feminine’ and of the social practices that ‘institute and maintain’ gender identities as ‘norms of intelligibility’. I shall return to the issue of Wedekind’s social commentary at the end of this essay, but now turn to how Berg’s music plays out this conception of the Lulu character and to how the composer stages his own authorial comment in sound.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Daniela Sindram (Geschwitz) & Marlis Petersen (Lulu) | Bayerische Staatsoper, 2015

III. THREE EMBLEMATIC MUSICAL PASSAGES

Critics identify three musical instances as emblematic of the Lulu character. While concurring that these passages play decisive roles in the musico-dramatic characterisation of Lulu, I shall offer an understanding of how the music contributes to this characterisation that differs from earlier critics. In particular, I will show how the music supports the idea of Lulu as a parodic character that performs the idea of the ‘feminine’ as performance. The three passages are (i) Lulu’s ‘Freedom’ music, (ii) the ‘Coda’ music of the Sonata and (iii) Lulu’s Lied. Since Lulu’s Freedom music and the Coda music share certain structural, dramatic and affective features, I consider them together here. Both are recurrent passages that George Perle calls Leitsektionen, and he understands the two as ‘special Leitsektionen that embody concepts governing the work as a whole’. The recurrence of these musical types, their association with significant dramatic moments and their characteristic musical attributes establish their significance for the opera generally. First, a brief description of each.

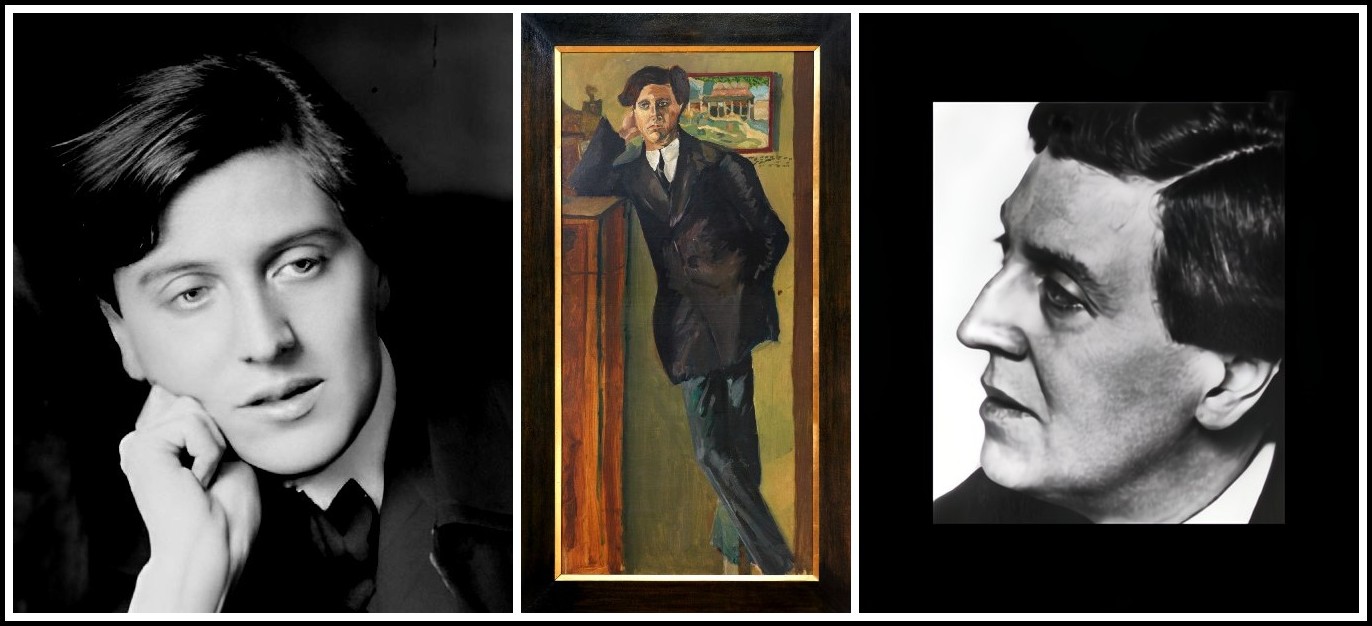

ALBAN BERG: Alban Berg Foundation | Arnold Schönberg, 1910, Wien Museum | Trude Fleischmann, 1932

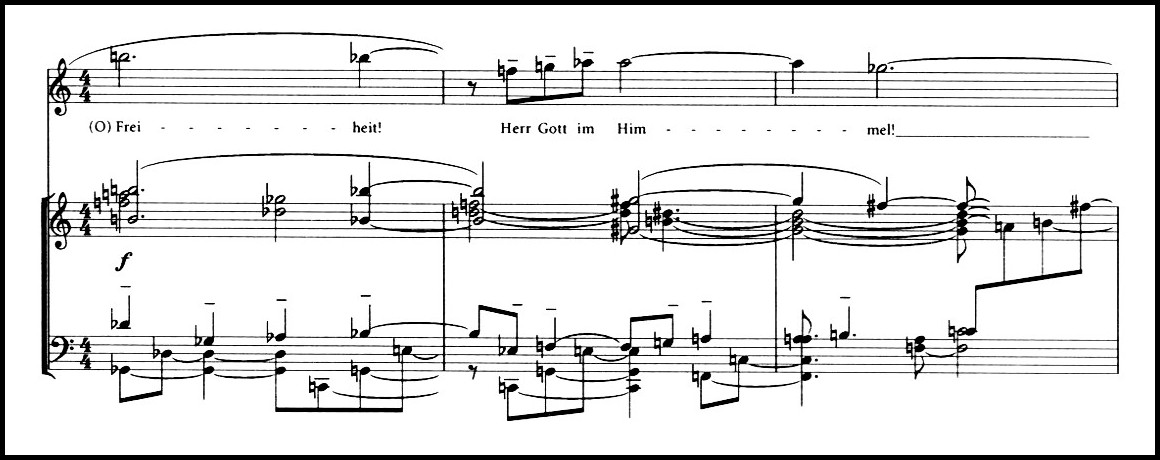

I name the Freedom music after its occurrence in Act II scene 2 when Lulu, returning home from prison, sings out the passionate cry of ‘Freedom’. Example 12.1 cites its opening bars. The Freedom music occurs in several places both before and after the Act II scene 2 statement: in the Prologue when the Animal Tamer brings Lulu onto the stage as a snake; in Act II scene 1 when Lulu, now married to Schön, comes down the grand staircase in his house to greet her ‘admirers’; and in Act III scene 2 just preceding Jack’s murder of Lulu (there are brief references to it elsewhere in the opera, but I am not counting these as ‘occurrences’). As the opening bars of the music suggest, the Freedom music is characterised by triadic harmonies—especially in the bass patterns—and by suspension-like melodic figures.

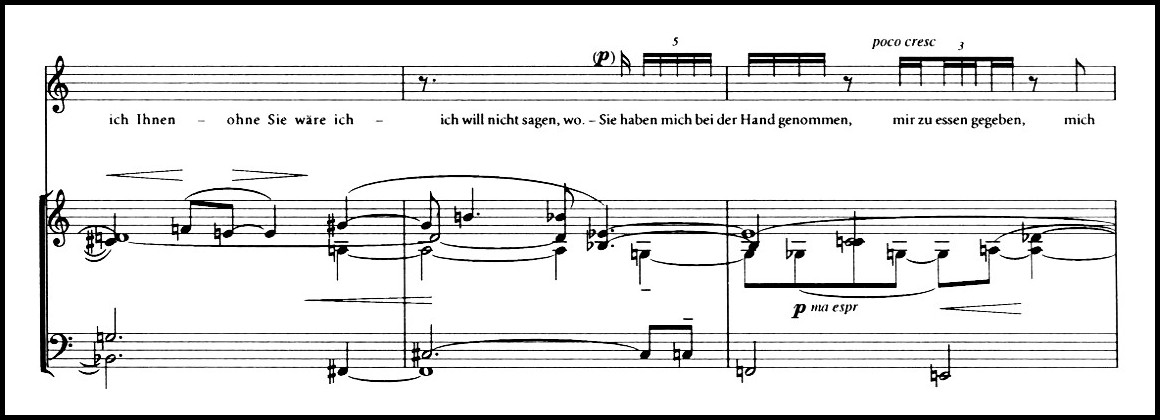

Example 12.1 – Lulu’s ‘Freedom’ music (Act II scene 2, bars II/1001-3)

Donald Mitchell, referring to the Freedom music accompanying Lulu’s return from prison (Act II scene 2), writes that it is ‘perhaps the most moving music in the whole opera. Berg’s music tells us most beautifully that she has suffered’. And Leo Treitler, writing of the Freedom Music more generally, calls it ‘radiantly gorgeous music which sings her identity’. For these authors, the Freedom music has a ‘beautiful’ and ‘gorgeous’ sound which projects Lulu as an authentic and authentically-feeling character. The Coda music has been similarly characterised as emotionally evocative. Douglas Jarman describes it as the ‘rich, Mahlerian Coda theme’ and Donald Mitchell points out that ‘the exceptional beauty of this passage leaves us in no doubt as to the depth of Lulu’s love’, an assessment to which George Perle assents. Example 12.2 cites its first appearance in Act I scene 2. Like Lulu’s Freedom music, the Coda music uses triadic sonorities that have tonal associations, and appoggiatura-like melodic figures. And, like the Freedom music, the Coda music is associated with intense and authentic feelings.

Example 12.2 – The Coda music (Act I scene 2, bars I/615-20)

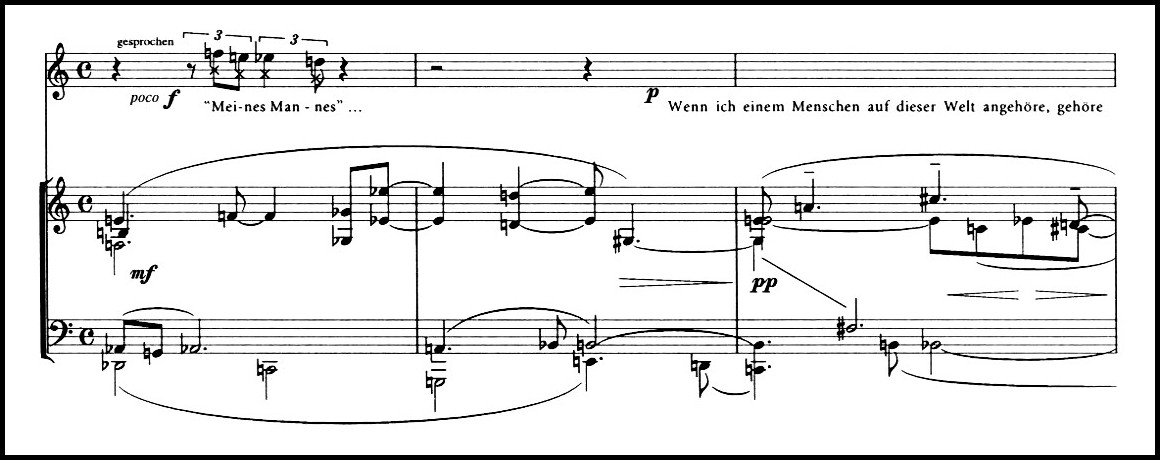

The emotional implications of the Coda music arise in part from its initial dramatic associations. It first occurs in Act I scene 2 as the conclusion of the Sonata exposition which literally and metaphorically stages an argument between Schön and Lulu—a confrontation between these two which is metaphorically projected by the opposition of row transpositions associated with each in the first and second theme groups. During the Coda music, Lulu speaks—note how her not singing enhances the melodramatic effect—about her allegiance to Schön, motivating it by the care he showed towards her when she was a young, poor child on the street. The Coda music occurs again as the conclusion of the Sonata’s reprise at the end of Act I. After agreeing to cut off his engagement to another woman and marry Lulu, Schön bemoans what he feels to be his impending execution, admitting what Jarman calls his ‘fatal inability to break free of Lulu’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petibon (Lulu) & Michael Volle (Schön) | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The Coda music occurs for a last time in the final scene of the opera just before Jack the Ripper murders Lulu and then Geschwitz. This final statement of the Coda music leads directly and smoothly into a final statement of the Freedom music.

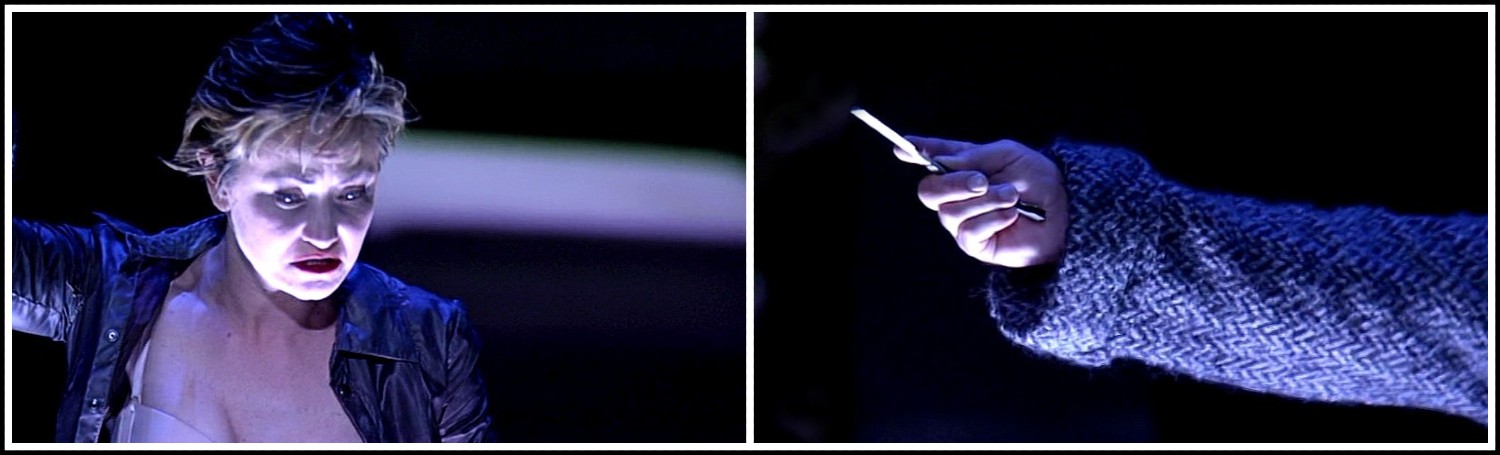

Alban Berg, Lulu, Dietrich Henschel (Jack the Ripper) & Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

Both the Freedom and Coda musics feature tonally implicative voice-leading in their melodies and make use of triad-based harmonies. Description of the music as ‘beautiful’, ‘gorgeous’ and ‘memorable’ attach to these passages largely because their ‘tonal’ attributes in a ‘non-tonal’ context mark them as ‘different’. In other words, these passages (as well as some others in the opera) use procedures of tonal music that are sometimes more, sometimes less explicit, but their effect depends on this sounding feature. Berg, having made the compositional decision to use the ‘tonal sound’ in these passages, did so, we must assume, for musico-dramatic effect. Understanding this effect begins with consideration of the historical context which situates both Berg’s compositional choices and the musical significance of those choices. Compared with the music of the Lulu period, Berg’s earlier works, such as the Altenberg Lieder and Wozzeck, demonstrate a more consistent quality of sound: the ‘atonal’ sound that characterises the Second Viennese School. In the later works, including Lulu, he incorporates passages with a tonally-implicative sound, juxtaposing ‘tonal’ with ‘atonal. In other words, his compositional ‘voice’ and expressive palette expand. In appropriating a Mahlerian musical style and juxtaposing it with the predominant ‘sound’ of the opera, Berg employs a particular kind of expressive strategy.

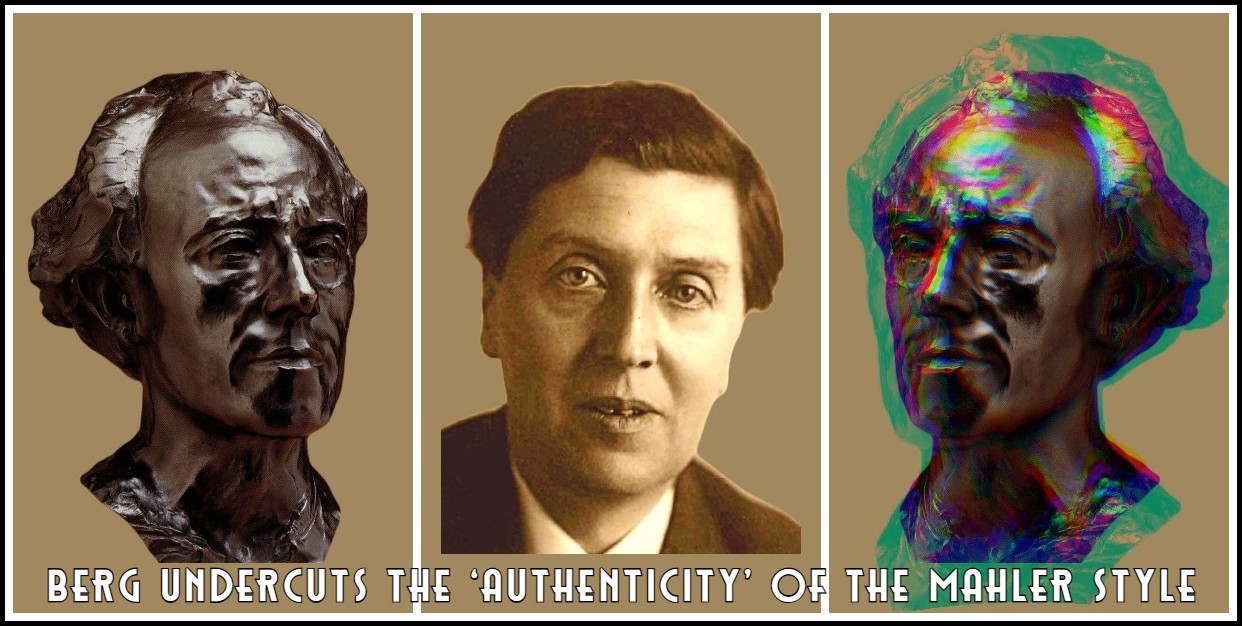

Zurich Opera House, Wozzeck, 2015 | Gustav Mahler, 1907, Vienna Opera | Robert Wilson & Berliner Ensemble, Lulu, 2011

Berg’s expanded compositional voice raises a number of questions: What does the ‘tonally-implicative’ music express? Does Berg use this Mahlerian style to imbue characters with feeling, to give them heartfelt emotion? Does he imitate this musical style in order to project the kind of expressive content the ‘original’ Mahler style would have had? Or does he imitate the style in order to parody the expressive content of the original? A ‘Mahlerian’ style is not an ‘authentic’ musical language for Berg in the Lulu period; it is one he appropriates. In imitating the style—a style which listeners accept and understand in its ‘original’ context as having emotional content—Berg does not replicate but rather undercuts the ‘authenticity’ of this content. Berg’s parodic implementation of musical style here reinforces the exaggerated gender roles that Lulu and the other characters inhabit in the drama. The sound of the Freedom and Coda musics parodies a Mahlerian emotional content and undercuts any sense of an emotional authenticity that might attach to the dramatic situation.

Auguste Rodin, Bust of Gustav Mahler, 1909 | Alban Berg, 1930

The instance of the Freedom music which critics have understood as projecting Lulu’s feelings and identity occurs after her escape from prison, an escape organised by Geschwitz, and her subsequent return to Schön’s home where Alwa awaits her (Act II scene 2, bars II/1001ff.). The passage that precedes Lulu’s ‘passionate’ display in the Freedom music (II/953ff.) tells us about her illness through its lethargic tempo. The music moves in slow motion as Schigolch escorts Lulu to the room where Alwa waits for her. Immediately upon Schigolch’s exit Lulu finds the strength to pour out her emotions on the high B♮ of ‘Freedom’ and celebrate her liberation (II/1001). But surely Lulu, the consummate performer who has learned her feminine skills well, has other concerns at this moment. She is suddenly left alone with Alwa, the son of the man she has been convicted of murdering, and who gave her up to the police at the end of the previous scene. Lulu cannot be sure of Alwa’s feelings towards her in the wake of his father’s death, and in order to ensure her own preservation she must utilise her ‘feminine’ skills to influence Alwa’s actions and feelings. Lulu performs her seductive charm through the borrowed expressivity of the Mahlerian style. The sounds pull us, and Alwa, into their seductive orbit. But, while Alwa falls completely under Lulu’s Mahlerian allure, the effect on the audience hearing his seduction is quite different. The larger musical context prompts a hearing of the Freedom music as an exaggerated and appropriated ‘romantic’ sound that, right on cue, pours out Lulu’s feelings.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Piffka (Alwa) & Patricia Petibon (Lulu) | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

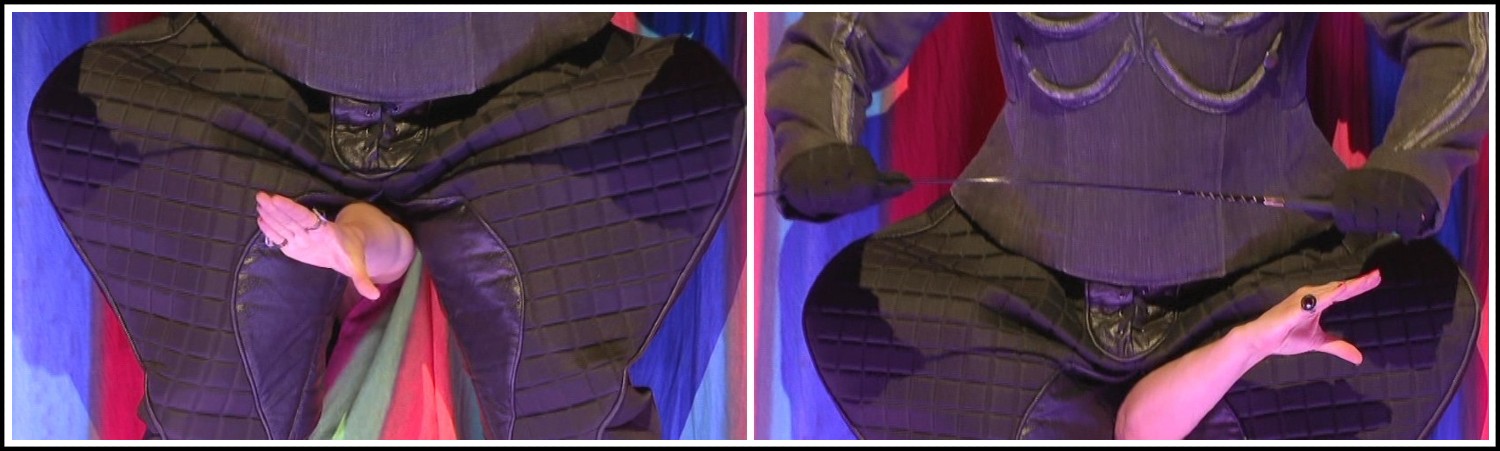

The two prior occurrences of the Freedom music contribute to this hearing. It first occurs in the Prologue and then again in Act II scene 1, in the action preceding Schön’s death. These prior occurrences reverberate in the Act II scene 2 version, magnifying the seductive and manipulative implications of Lulu’s passionate outburst of ‘freedom’. The Freedom music in the Prologue (bars 44ff.) accompanies Lulu’s first on-stage appearance. Having introduced all the other animals which are ‘waiting behind the curtain’, the Animal Tamer calls for the snake to be brought out: the Freedom music accompanies the Stage Hand, as he carries the soprano who sings Lulu on stage, and then the Animal Tamer as he playfully describes ‘this creature created to make trouble, to tempt, to seduce, to poison and to murder without anyone noticing’. The combination of the Mahlerian sound of the Freedom music with the explicit articulation of the ‘Woman as Temptress’ myth through the Animal Tamer’s words and the imagery of the snake has the effect of subverting both the meaning of the myth and the authenticity of the musical style.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Thomas Johannes Mayer (Animal Tamer) & Patricia Petibon (Lulu, hand & forearm)| Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The second occurrence of the Freedom music, in Act II scene 1 (bars II/145ff.), restages the myth of ‘Woman as Temptress’. Between the end of Act I and the beginning of Act II, Lulu has married Schön, an event which signals the peak of her ‘feminine’ powers. The potency of her allure is made evident by the male admirers running about Schön’s house in this scene. After initial exchanges with Geschwitz and Lulu, Schön leaves the stage, but instead of going to the Stock Exchange as claimed, he stays to spy on Lulu. Thinking her husband has left, Lulu turns her attentions to the admirers running about the house. As the fawning men and boys flutter around her, the Freedom music accompanies her flirtatious banter with the Acrobat (II/209-23). Clearly enjoying the powers of her seductive charms, Lulu engages her admirers in a playful and erotic exchange.

Alban Berg, Lulu | Pavlo Hunka (Schigolch), Marlis Petersen (Lulu), Martin Winkler (Acrobat), Rachel Wilson (Schoolboy) | Bayerische Staatorchester, Kirill Petrenko, 2015

These instances of the Freedom music resound in its occurrence in Act II scene 2. The subversion of musical and mythical meaning from the Prologue’s Freedom music and the sense of playfully seductive manipulation from Act II scene l’s version affect its meaning here. Now an escaped convict, Lulu can no longer use her seductive charms merely in play; the efficacy of her allure can mean the difference between freedom and incarceration, between life and death. Lulu chooses to perform the feminine role of ‘Woman as Temptress’ in order to preserve herself. What is more, hearing the ‘Temptress’ role as a performance of preservation in the Act II scene 2 version of the Freedom music reinterprets its meaning in prior instances. The later performance recasts earlier presentations of Feminine Myth and Allure as ‘deadly serious’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Act II Scene 2 | Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) & Charles Workman (Alwa) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

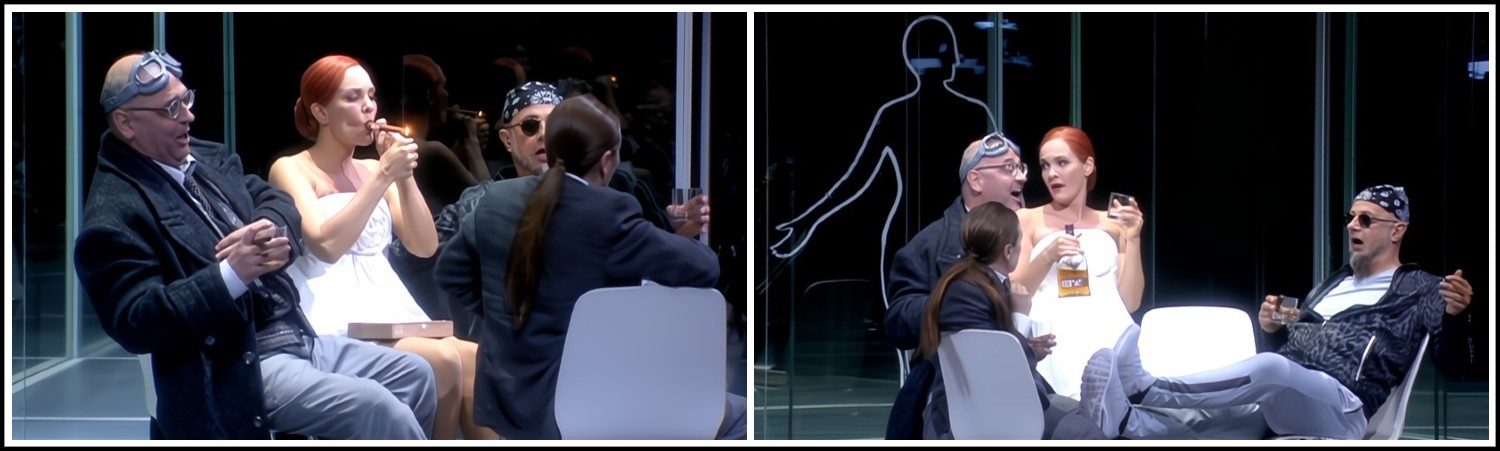

The Coda music first occurs at the end of the exposition of the Sonata in Act I scene 2 (bars I/615ff.) and is linked to Lulu’s love and allegiance to Schön. Throughout the exposition, Schön and Lulu argue. He wants to cut off their relationship; she complains about her life with the Painter, a life of boring comfort arranged and controlled by Schön. Unable to sway Schön through confrontation, she tries emotional seduction. The Mahlerian Coda music creates an emotionally allusive environment in which Lulu can convince Schön of her love for him through reminiscence and declarations of devotion. The Coda music, with its triadic harmonies and ‘longing’ appoggiaturas, ‘changes the subject’ from confrontational dialogue to warm sentimentality which will ‘melt’ Schön’s heart. Lulu wields her feminine power in the melodramatic narrative through the ‘overpowering’ aura of tonal implication. The effectiveness of Lulu’s seductive performance manifests itself in the occurrence of the Coda music at the end of Act I scene 3. Concluding the Sonata’s recapitulation, this version of the Coda music (bars I/1356ff.) accompanies Schön’s proclamation of what he perceives to be his own impending ‘execution’. Unable to free himself from Lulu’s feminine powers, Schön gives voice to his powerlessness with the same music that Lulu uses to seduce him, the Coda music. The music which plays out Lulu’s feminine power recurs to play out the impotence it effects in Schön. The exaggerated emotional content of Schön’s words—‘Now comes the execution’—is magnified by the parodic imitation of a ‘romantic’ sound.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Act I Scene 3 | Patricia Petibon (Lulu) & Michael Volle (Schön) | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

The musical projection of Lulu as a character that performs a critique of the ‘feminine’ as a ‘socially instituted and maintained norm of identity’ derives not only from the parodic imitations of a Mahlerian style in the Freedom and Coda musics but also from another strategy that works something like parody: pastiche. Both parody and pastiche involve the imitation or borrowing of something prior, but pastiche creates its meaning by assembling and juxtaposing prior ideas. While noting the relationship between parody and pastiche, Frederic Jameson suggests that pastiche has none of the ‘satirical impulse’ of parody. The third of the passages considered by prior critics as emblematic of Lulu’s identity, Lulu’s Lied, employs a strategy of pastiche. George Perle in particular focuses on the significance of Lulu’s Lied, calling it her ‘great aria of self-awareness’. Perle gives a fairly detailed analysis of the Lied’s pitch and formal structure, but he does not comment on how these compositional choices relate to the Lied’s dramatic significance.

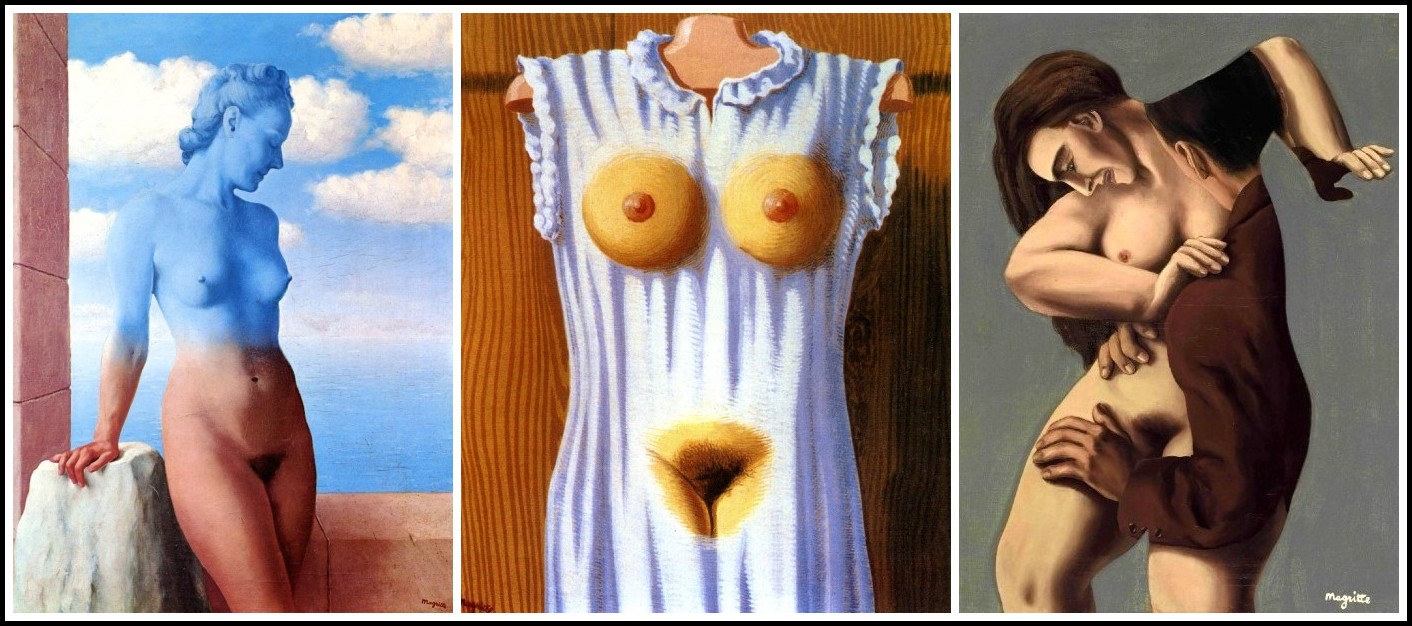

THREE EXAMPLES OF PASTICHE

Pastiche of the ‘moderne’ style: Robert Block, Dressing Table, 1935 | Playing with the visual codes of femininity / painting / photography: Cindy Sherman, Untitled # 199, 1989 | ‘Postmodern historicism’: Venturi Scott Brown, Chippendale Chair, 1984

The Lied occurs in the midst of Schön’s five-strophe Aria in Act II scene 1 (the Aria occupies bars II/380-490 and 539-51; Lulu’s Lied, II/491-538). Schön, presumed out of the house, is in hiding and observes Lulu’s flirtatious exchanges with her various admirers. He eventually confronts her soon after Alwa, Schön’s son, declares his love for Lulu. After escorting Alwa out of the room, Schön returns and presses Lulu to kill herself. She suggests that divorce is a better solution, but he, quite hysterical by now, will hear nothing of it. Lulu responds with the Lied in which she verbally defends herself. She presents five arguments, each of which corresponds to a formal unit of the Lied:

1. Lulu’s worth or value as a person is not diminished because people kill themselves over her

2. Schön went into the marriage with his eyes open

3. Schön has not only fooled his friends over who she is, he has fooled himself

4. Lulu gave up her youth to Schön, which is no less important than his giving up his old age for her

5. Lulu has never tried to be anything other than what she ‘is’

The text of Lulu’s Lied provides information about her and Schon: Lulu has a strong sense of self and Schön has been deluding himself about her. But beyond that, however, the song provides little detail on how the Lulu character defines herself and what motivates her actions. In other words, the text falls short of the strong statement of ‘self-awareness’ Perle asserts. Berg’s music sheds important light on an understanding of the dramatic role the Lied plays in the opera.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Act II Scene 1 | Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) & Dietrich Henschel (Schön) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

As Perle has noted, the Lied has five phrase units or ‘periods’. Each period has an antecedent/consequent phrase structure in which the vocal and instrumental lines of the consequent invert those of the antecedent. In the first period (II/491-7), Lulu sings a melody fashioned from the Basic Series for the antecedent and from the inverted series for the consequent; the orchestra plays chords which are formed from the Basic Series and which are heard in association with Lulu’s interactions with the Painter in the opera’s first scene. In the second period (II/498-507) the orchestra plays a theme associated with Lulu—the ‘Lulu Melody’—based on Lulu’s series, which in turn is derived from the trichordal partitioning of the Basic Series into the ‘Picture Chords’. This melody forms the thematic basis of the Canon in Act I scene 1 which accompanies a flirtatious game of chase between Lulu and the Painter. The third period (II/508-15) presents an octatonic melody in the vocal part which arises as the top voice of successive statements of the Picture Chords. The fourth and fifth periods re-present in retrograde the melodic strategies of the first and second periods: the fourth period (II/516-21) plays ‘Lulu’s Melody’ as did the second period, and the fifth period (II/522-36) plays a melody based on the Basic Series as did the first period; each of the two parts of this period is extended with statements of the ‘Erdgeist Fourths’ motive. The Lied’s short, concluding music in the orchestra (II/536-8) states a version of a tune, based on Alwa’s series, which is featured in music accompanying Lulu’s conversation with him prior to her confrontation with Schön. In the earlier exchange, Lulu sings the tune in inversion as she asks of Alwa: ‘Do you love me then?’ At the end of the Lied, the tune is supported in the bass by a triad that supports the implied E♭ minor tonality of the tune and states the first three notes of an inverted form of Schön’s series.

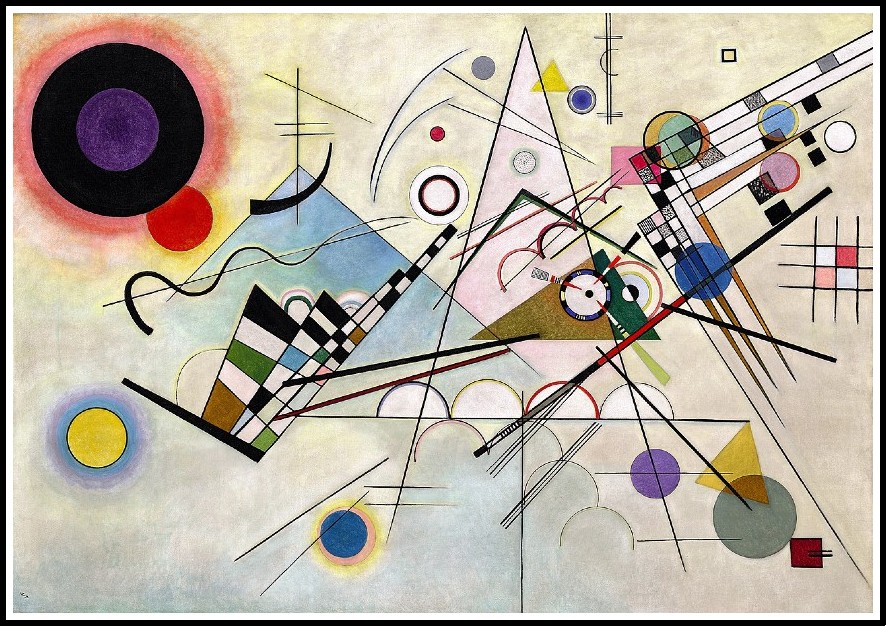

Kandinsky, Composition VIII, 1923

The various musical references to other characters and earlier events in the opera do not support an understanding of the Lied as a unified statement of Lulu’s identity. The Lied refers to musical constructions associated explicitly with Lulu, but even these—unlike the tunes and constructions associated with Schön, Alwa and some of the others in the drama—do not attempt to define an ‘authentic’ character: the Lulu Melody is based on a linearisation of the Picture Chords, and the Picture Chords, themselves a trichordal partition of the Basic Series, are associated with her depiction as Pierrot. Rather than a musical embodiment of her ‘authentic’ identity, the Lied is collage-like in its sonorous depiction of recent events in Lulu’s life. The character that emerges from this pastiche of past events and associations is self-assured, but her self-awareness is not directed inwards. The music reflects her awareness of the immediate situation: its sounds inform us about her and those people with whom she has had dealings. Lulu knows that she must deflect Schön’s hysterical anger: he is raging and has threatened her with death. She presents him with a textual and musical pastiche of prior events that has the immediate goal of defusing his rage, but at the same time this pastiche has the effect of deriding his blustering anger.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Patricia Petibon & Michael Volle (Wiener Philharmoniker, 2010) | Nadar, Sarah Bernhardt as Pierrot, 1883

Douglas Jarman suggests that the ‘disturbing difference between the emotional attitude adopted by the music and the nature of the text to which it is set’ is part of Lulu’s ‘subversive’ strategy. Robin Holloway also notes the ‘subversive’ element in Lulu’s music when he writes that Lulu ‘undermines its listeners’ obedience to emotive instructions’. Holloway’s observation of the subversive element of the opera in general—and, I would add, of the Lulu character in particular—resonates directly with the points I have been making about the Freedom and Coda musics and indirectly with those regarding Lulu’s Lied.

Christine Schäfer, Pierrot Lunaire, Schönberg | Gustav Mahler

As discussion above has demonstrated, the musical and dramatic contexts in which the Freedom and Coda musics occur, and the context of Berg’s own compositional history, provide a framework for an understanding of the two musical passages that ‘undermines’ a ‘typical’ emotive response to their Mahlerian style. This framework also sets up a larger subversion of the ‘feminine’ by depicting both the particular emotive response and the feminine identity as performative choices. In the end, the subversive musico-dramatic goals of Lulu produce a situation in which ‘the disturbing difference between emotional attitude and text’ does not arise. The ‘disturbing’ effect occurs only if listeners respond ‘typically’ to the Mahlerian imitation. If listeners hear the Freedom and Coda musics as parodic imitation, then a sense of the Lulu character as critique of the ‘feminine’ emerges. While the underlying strategy of subversion operates in Lulu’s Lied, the particulars of its deployment are quite distinct from the Freedom and Coda musics. The Lied does not tempt listeners with a ‘typical’ emotive response, but rather saturates them with a succession of musical associations which simultaneously depict a dramatic history and coolly play out Lulu’s response to Schön’s hysterical ranting. The music of the Lied does not open a window onto an ‘authentic’ Lulu whose ‘human nature’ underlies her ‘heroic struggle against the Marquis’; rather, it embodies a character whose actions reflect her history, her self-awareness and her strategies for self-preservation.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Dietrich Henschel (Schön) & Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

IV. BERG’S OWN VOICE

I return now to the issue of Wedekind’s social commentary and how Berg’s music plays out an authorial comment in sound. Earlier I suggested that Wedekind makes an authorial comment on the destructive aspects of the ‘feminine’ as performative choice within a patriarchal society through Lulu’s murder at the hands of Jack the Ripper. Jack is the one character in the drama over whom Lulu’s ‘femininity’ does not have a mesmerising effect. Her feminine performance does not enchant him but leads instead to her own death. The lesson Wedekind enforces here is not that of a misogynistic patriarchal order but rather that of the devitalising effects of a social order that insists on certain forms of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ behaviour. This assessment of Wedekind’s commentary is shared by various critics of Berg’s opera. Treitler writes that ‘The deaths in the opera—and now I mean all of them—are the ravages of socio- and psychosexual struggle’. And Jarman asserts that the opera forces us to pity and identify with ‘all the characters helplessly trapped in this grotesque Totentanz’ and ‘to face our moral responsibility for the society depicted on stage’.

Carolein Smit, Totentanz, 2017-21

Berg, adopting Wedekind’s authorial comment, uses the opportunities afforded him by music to make it more palpable and more emotionally direct. The sound of Lulu’s death cry and its orchestral aftermath near the opera’s end (bars III/1294ff.) compel us to feel intensely the tragedy that is marked by Lulu’s death. The shrieking strings stab us, Berg making it painfully clear how we are to feel about this death. Lulu is the symbol of this comprehensive social tragedy since, as archetypal Woman, she bears the greatest social burden: she is the scapegoat for society’s evil, she is Pandora, she is Eve. But the tragedy is not hers alone. It belongs to all the men and the women who participate in this ‘Totentanz’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Tanja Ariane Baumgartner (Geschwitz), Patricia Petibon (Lulu), Michael Volle (Jack the Ripper) | Wiener Philharmoniker, Marc Albrecht, 2010

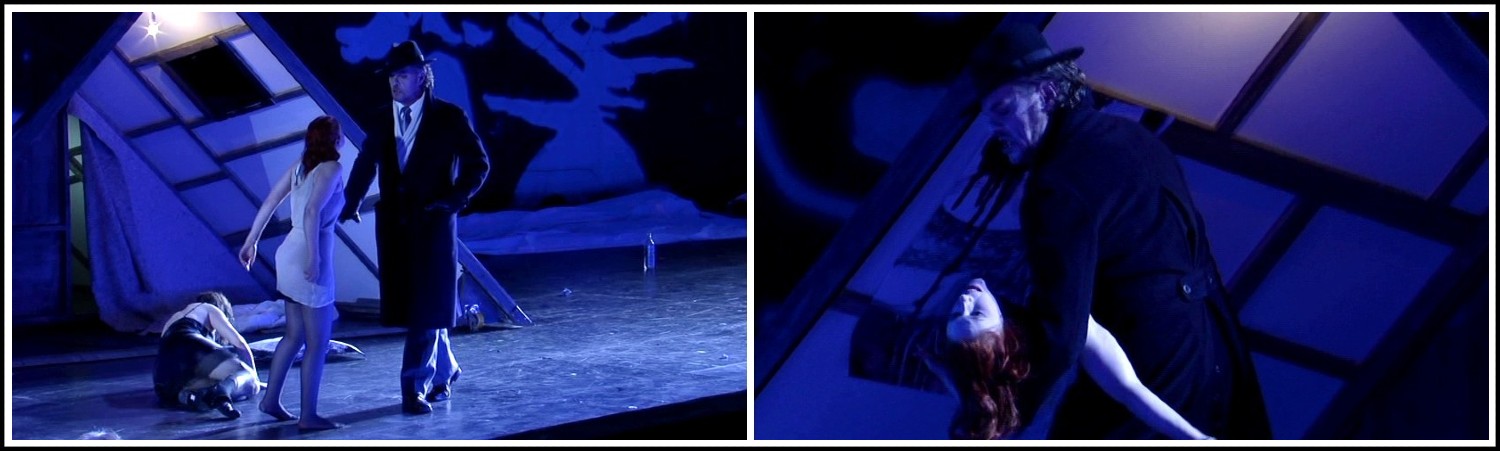

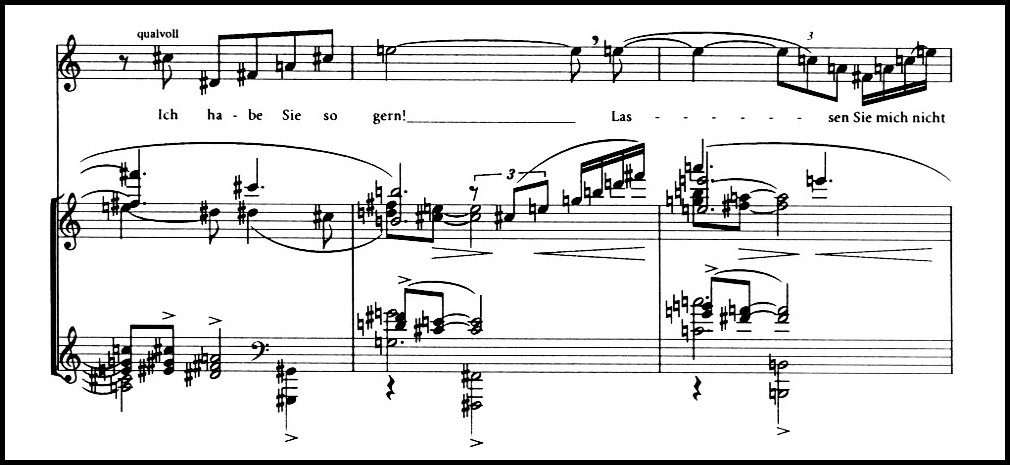

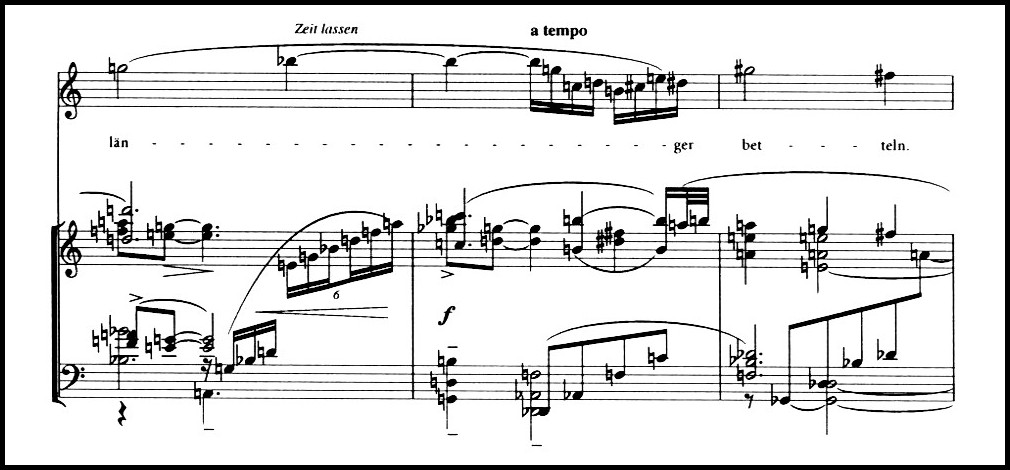

The effectiveness of Berg’s authorial comment arises not simply from his orchestrational skill at the moment of Lulu’s death but further from the way he prepares us for this event in the concluding exchange between Jack and Lulu (bars III/1258ff.). Just before they retire to an inner room, Jack tells Lulu that they have no need for the lamp she is carrying—we realise this is so he can wield his knife without her immediate knowledge—and she articulates her desire to be with him. During this exchange the orchestra plays the Coda music which imperceptibly transforms into the Freedom music. The passage climaxes at that point in the Freedom music which juxtaposes two tritone-related triads as Lulu says ‘Don’t make me beg any longer’ (Example 12.3).

Example 12.3 – Fusion of Coda and ‘Freedom’ musics (Act III scene 3, bars III/1276-81)

Berg’s fusing of the Freedom and Coda musics at this crucial moment in Lulu attests to the significance of these passages for the opera as a whole. But in this context, their musico-dramatic meanings have been transmuted. The balance of power has changed in this passage. No longer in control, Lulu must now employ the Freedom music—music which was her powerfully seductive medium—to beg. And the Coda music—which she employed to foster Schön’s sentimentality—now sets her surrender to Jack’s wishes. Rather than exaggerated and melodramatic vehicles for Lulu’s feminine performances in order to sway and seduce those who would control her, the Coda and Freedom musics have become sounding commentary on the tragic outcome of the ‘socially instituted and maintained norms of intelligibility’ that have given rise to Lulu’s ‘feminine performance’.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Laura Aikin (Lulu) & Alfred Muff (Jack the Ripper) | Zurich Opera House, Franz Welser-Möst, 2002

Berg’s authorial comment on the tragedy of a social order that insists on certain forms of ‘feminine’ and ‘masculine’ behaviour operates in two stages: first, by depicting Lulu as an exaggeration of the ‘feminine’ and thereby demonstrating ‘feminine’ behaviour as a performative choice through parody of the emotive content implied in the Mahlerian style; and second, by using the parodic music to portray a situation in which the performative strategies are no longer effective. The force of Berg’s authorial comment in the orchestral response to Lulu’s death arises not simply from the qualitative features of its sounds but from those sounds in conjunction with the transformation of meaning that attaches to the Coda and Freedom musics in the exchange between Jack and Lulu.

Lulu meets Jack the Ripper: ‘The performative strategies are no longer effective.’

V. CONCLUSION

Butler’s concept of performative choice provides a means for understanding Lulu’s various contradictory attributes and her non-unified character. In addition, issues of authenticity surrounding performativity and identity illuminate those musical features of Lulu that critics have found ‘disturbing’—the disjunction between music and dramatic action.

MAGRITTE: Attempting the Impossible, 1928 | The Rape, 1945 | Eternal Evidence, 1930

The Lulu character performatively exaggerates her femininity, and her music orchestrates that performance through parody and pastiche. Berg emerges from behind the parodic veil at the opera’s end, however. Through the fusing of the Coda and Freedom musics and the shrieking strings that tell us of Lulu’s death, Berg makes his position strikingly clear. While Lulu dies literally at the hand of Jack the Ripper, she also dies symbolically from the ‘social norms of intelligibility’ that dictate certain gendered behaviours. Through parodic exaggeration and pastiche, Berg’s music makes us palpably feel the tragic consequences of Lulu’s feminine performance.

Alban Berg, Lulu, Barbara Hannigan (Lulu) & Dietrich Henschel (Jack the Ripper) | Orchestre Symphonique de la Monnaie, Paul Daniel, 2012

JUDITH LOCHHEAD: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments