Writing and Eroticism as Liberation and Self-Creation

MARGUERITE DURAS: THE LOVER – IMAGE AND ABSENCE

Nina Hellerstein

Posted by kind permission of Nina Hellerstein, Professor Emerita of French, Department of Romance Languages, University of Georgia

From Nina S. Hellerstein, ‘Image’ and Absence in Marguerite Duras’ L’Amant (Modern Language Studies, Vol. 21 No. 2, Spring 1991) 45-56

All citations from the novel are given in French, in italics, followed by the page number(s) from the 1984 Minuit edition of Marguerite Duras’ L’Amant.

Marguerite Duras

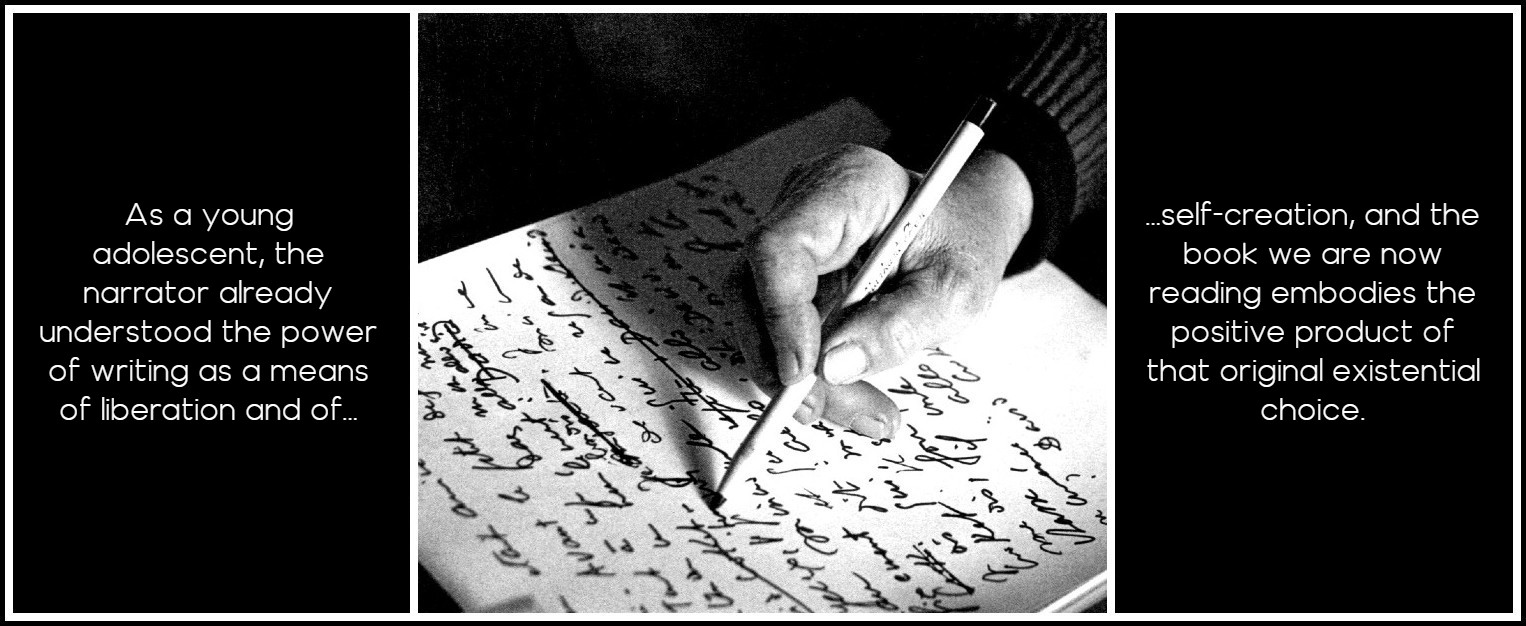

The essential subject matter of Marguerite Duras’ L’Amant is the haunting evocation of a young girl’s first love affair; but underlying this basic plot is a subtle dialectical interplay between creation and destruction, between presence and absence, reality and void, reflecting Duras’ permanent preoccupation with these themes, on both the psychological and metaphysical levels, throughout her career. The human relationships which are the center of the novel are all constructed along the lines of this fundamental opposition; but more importantly, the creation of the text itself appears as a product of the subtle interaction between the two forces. The concept which embodies the positive, creative, concrete side of the dialectic is the ‘image’. The term recurs constantly throughout the book, and designates the essential law of its construction. The novel is a series of images which the narrator, looking back on her past, summons up in order to explore her own evolution and to understand her present self better. This creative function of the image is linked with the role of writing itself in the novel; long ago, as a young adolescent, the narrator already understood the power of writing as a means of liberation and of self-creation, and the book we are now reading embodies the positive product of that original existential choice.

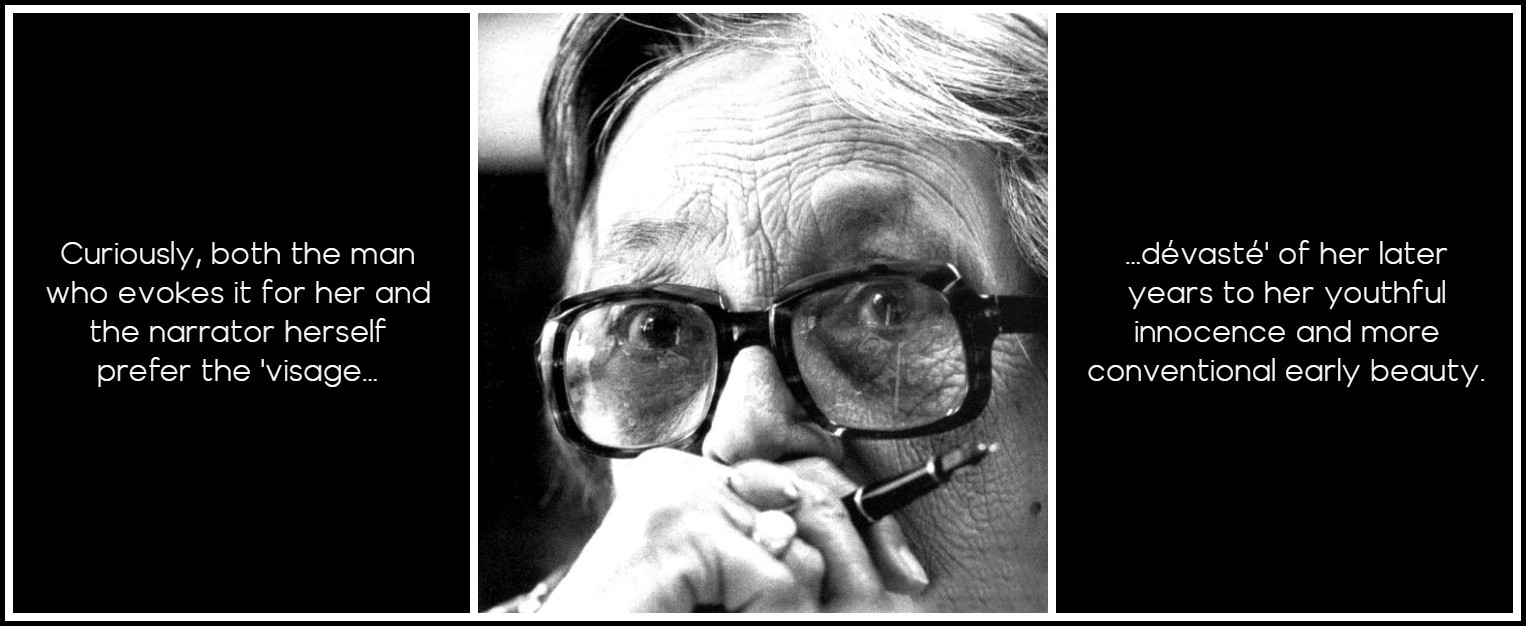

Marguerite Duras

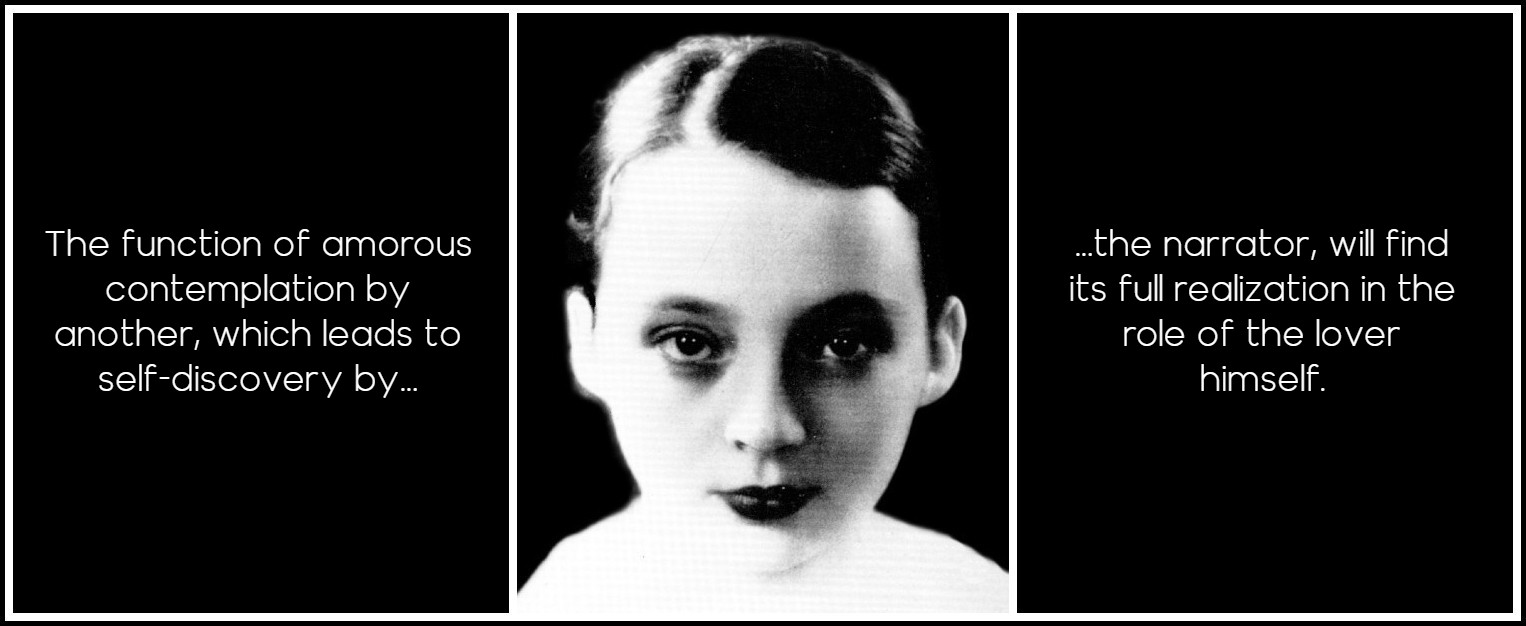

This creative function of the image is the point of departure of the novel: it begins with the image presented to the narrator by the man who comes up to her in le hall d’un lieu public (9) and who contrasts her past appearance with the face she wears now. This experience sets up the framework upon which the novel will be constructed: the exterior, anonymous point of view, directed at the outward face of the narrator, serves as a means of self-discovery. It allows the narrator to measure the inner meaning of her life, by contemplating the echoes it has evoked in others. Je pense souvent à cette image que je suis seule à voir encore et dont je n’ai jamais parlé. Elle est toujours là dans le même silence, émerveillante. C’est entre toutes celle qui me plaît de moi-même, celle où je me reconnais, où je m’enchante (9). This form of image, like most of the others in the book, takes the form of the face, yet goes beyond simple physiognomy imposed by nature to imply voluntary creation. This first form of image also introduces other characteristics which will determine the subsequent development of the novel: for example, the man who proposes it to the narrator is unknown to her, yet his words suggest a romantic relationship, a form of amorous admiration: Je vous connais depuis toujours, pour moi je vous trouve plus belle maintenant que lorsque vous étiez jeune (9). This function of amorous contemplation by another, which leads to self-discovery by the narrator, will find its full realization in the role of the lover himself.

Marguerite Duras at age 18

Curiously, both the man who evokes it for her, and the narrator herself, prefer the ‘visage dévasté’ of her later years to her youthful innocence and more conventional early beauty. This paradox hides a central basis of the story: the idea that a life lived to the fullest, even if it means suffering and painful passions, is a creative and positive one, more worthwhile and admirable in its results than an existence protected from emotion and from time. Thus we understand from the very beginning that the narrator has lived through ‘devastating’ experiences, yet that she feels herself a richer and more complete person for them. The negative and positive sides of life are intimately bound up together, and the painful love affair the narrator is about to recount has had a positive, creative effect upon her life.

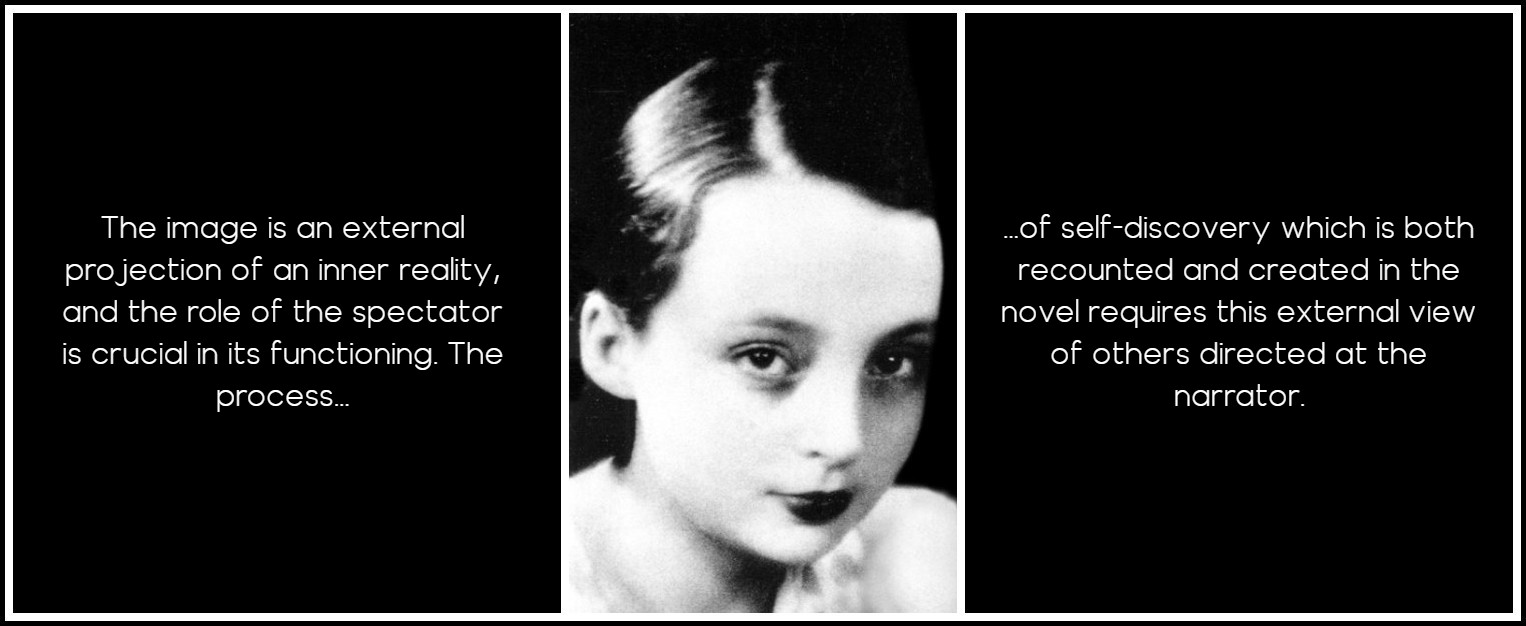

Marguerite Duras

The public nature of the first scene, and the anonymous quality of the man’s sudden appearance, represent another important part of the novel’s development. They are in fact consequences of the basic structure of the image: the image is an external projection of an inner reality, and the role of the spectator is crucial in its functioning. The process of self-discovery which is both recounted and created in the novel requires this external view of others directed at the narrator. Thus the man who appears at the beginning of the book continues a process which was set in motion many years before, when the heroine first became aware of herself as a free, separate being, with an independent sexuality: Soudain je me vois comme une autre, comme une autre serait vue, au-dehors, mise à la disposition de tous, mise dans la circulation des villes, des routes, du désir (20). Paradoxically, the narrator asserts her personality and independence by offering her outward self to the contemplation of those around her. The liberation of her body and her personality requires a collective, public context which will realize fully the potential she feels within herself. And she is able to utilize the regard and the attention of others in order to construct herself; looking at herself as others do enables her to choose consciously what she wants to be, instead of simply submitting to what nature has forced upon her. Sous le chapeau d’homme, la minceur ingrate de la forme, ce défaut de l’enfance, est devenue autre chose. Elle a cessé d’être une donnée brutale, fatale, de la nature. Elle est devenue, tout à l’opposé, un choix contrariant de celle-ci, un choix de l’esprit. Soudain, voilà qu’on l’a voulue. Soudain je me vois comme une autre (20). In the interchange between the spectator and herself as object, the heroine creates the self that she and the spectator wish her to be, and this act of self-creation constitutes a first and major step towards the conquest of full independence.

Marguerite Duras at age 18

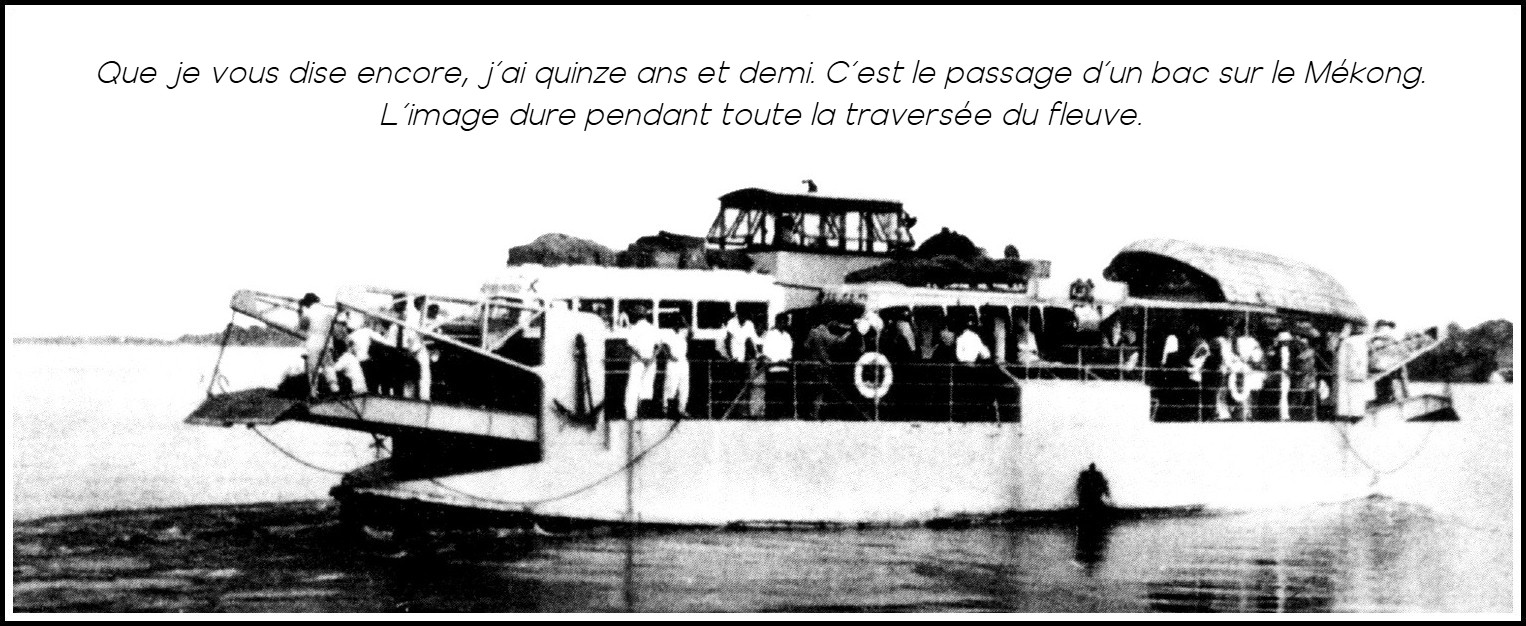

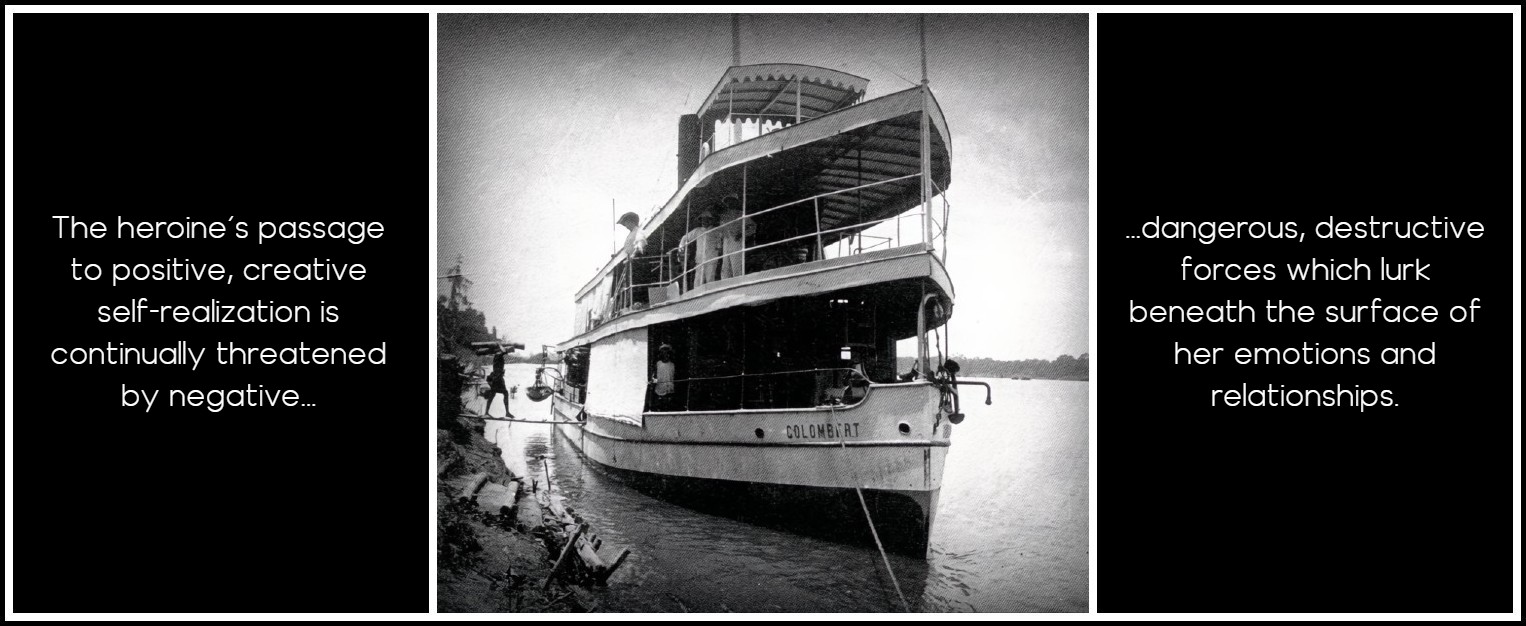

The appearance of the lover is carefully prepared to fit into this context. After the initial image has put the narration into motion, we are offered a series of subsequent images which have the function of presenting a progressively clearer picture of the young heroine, interspersed with meditations on the background of her life. Que je vous dise encore, j’ai quinze ans et demi. C’est le passage d’un bac sur le Mékong. L’image dure pendant toute la traversée du fleuve (11). We, the readers, and the narrator are the only spectators at the beginning of the novel, but gradually the spectators become more specifically identified with the young heroine’s contemporaries, and the lover is introduced as a member of this spectator group. Dans la limousine il y a un homme trés élégant qui me regarde. Ce n’est pas un blanc. Il est vêtu à l’européenne, il porte le costume de tussor clair des banquiers de Saigon. Il me regarde. J’ai déjà l’habitude qu’on me regarde. On regarde les blanches aux colonies, et les petites filles blanches de douze ans aussi (25).

Marguerite Duras | The Lover | Ferry on the Mekong

Gradually, through a complex web of flashbacks to other moments, flash-forwards to subsequent events, and meditations on the narrator’s tangled relationships with her family, the novel arrives at the central moment: the meeting of lover and heroine. L’homme élégant est descendu de la limousine, il fume une cigarette anglaise. Il regarde la jeune fille au feutre d’homme et aux chaussures d’or. Il vient vers elle lentement. C’est visible, il est intimidé (42). In this decisive moment, the problem of the narrator’s relations with her family, the theme of her self-creation through the regard of others, the role of her clothes, appearance and sexuality: all come together to make of the lover’s appearance the turning point in her life. For the lover is the heroine’s first true ‘spectator,’ he is destined to become the means of her full liberation because he offers her the external regard which allows her to become fully herself.

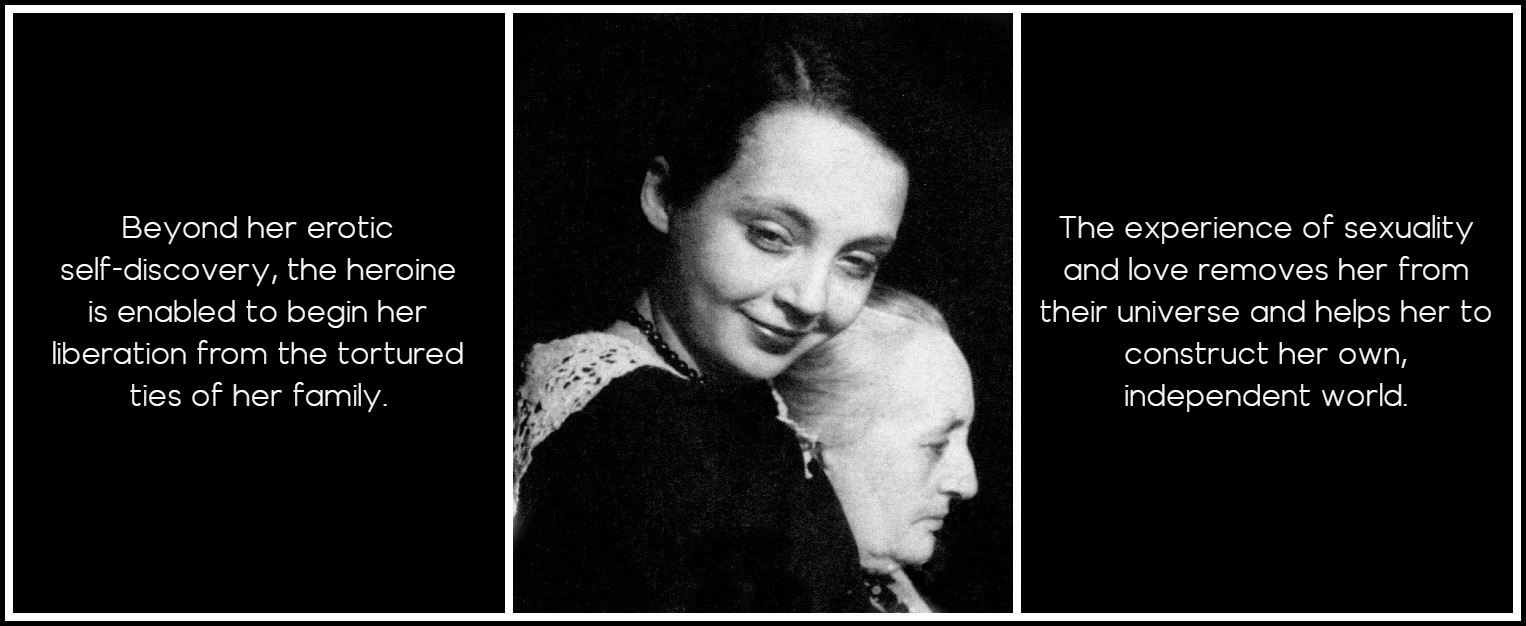

Marguerite Duras with her brothers Pierre and Paul

In the course of their love affair, this experience of self-discovery takes place on several different levels. The heroine discovers her body, through the sexual initiation which the lover offers her, and this experience is perhaps the most fundamental form of liberation. But beyond her erotic self-discovery, the heroine is also enabled to begin her liberation from the tortured ties of her family. The experience of sexuality and love removes her from their universe and helps her to construct her own, independent world. Dès qu’elle a pénétré dans l’auto noire, elle l’a su, elle est à l’écart de cette famille pour la première fois et pour toujours. Désormais ils ne doivent plus savoir ce qu’il adviendra d’elle. Qu’on la leur prenne, qu’on la leur emporte, qu’on la leur blesse, qu’on la leur gâche, ils ne doivent plus le savoir. Ni la mère, ni les frères. Ce sera désormais leur sort. C’est déjà à en pleurer dans la limousine noire. L’enfant maintenant aura à faire avec cet homme-là, le premier, celui qui s’est présenté sur le bac (46).

Marguerite Duras and her mother, Marie Donnadieu

Later, when the affair is more advanced, the effects of this first separation become more and more evident. The heroine is now able to detach herself from her mother for the first time: Elle connaît sa fille, cette enfant, il flotte autour de cette enfant, depuis quelque temps, un air d’étrangeté, une réserve, dirait-on, récente, qui retient l’attention, sa parole est plus lente encore que d’habitude, et elle si curieuse de tout elle est distraite, son regard a changé, elle est devenue spectatrice de sa mère même, du malheur de sa mère, on dirait qu’elle assiste à son événement (72-3). The terms ‘regard,’ ‘spectatrice,’ ‘assister’ show that the young heroine is in the process of conquering her own selfhood through her capacity to look at others. Her childish identification with her mother has given way to a more mature detachment, so that she is now aware of her own power to look at others and to understand them and herself. It is this gift, which the lover has given the heroine without even knowing it, which is the most precious and durable legacy of their affair.

Marguerite Duras and her mother, Marie Donnadieu

Thus, the novel’s exploration of the narrator’s past and present self is the result of this experience of self-discovery: the text is composed of the multiple images of herself and of others which the narrator creates for us. This power to create images explains even the narrative modes which govern the text: the narrator oscillates between the first and third person when describing herself, because she is evoking her own past alternately from her own personal, inner point of view and from the point of view of those around her. The lover, her mother, her brothers, the other members of her society: all are spectators, all direct a certain regard towards her, and each one of these points of view contributes to the total portrait of the heroine and the web of relationships which constitutes her life. Cela se passe dans le quartier mal famé de Cholen, chaque soir. Chaque soir cette petite vicieuse va se faire caresser le corps par un sale Chinois millionnaire. Elle est aussi au lycée où sont les petites filles blanches, les petites sportives blanches qui apprennent le crawl dans la piscine du Club Sportif. Un jour ordre leur sera donné de ne plus parler à la fille de l’institutrice de Sadec (109-10). The choice of terms here expresses simultaneously the shocked reactions of the conventional bourgeois of the French colony, and the narrator’s later, ironic judgment on this attitude.

Marguerite Duras at age 16 in Sadec, Indochina

The major function of the image, as it is presented to us through the various points of view used in the novel, is as a projection of inner reality which will enable this inner reality to become concrete, visible and knowable. And this function is intimately bound up with the action of time: the image solidifies and concretizes the appearance of the person at a moment in time, it allows the characters to see and to understand themselves outside the flow of time. The major form which this function of the image takes is the photograph; the work was originally conceived as a collection of commentaries on photographs of important moments and things in Duras’ life. Thus, numerous photographs appear at many stages of the novel, and they are always associated with the search for knowledge of oneself and others. The heroine evokes this with her lover: Je lui dis que ce n’est pas seulement parce que c’était pendant le jour, qu’il se trompe, que je suis dans une tristesse que j’attendais et qui ne vient que de moi. Que toujours j’ai été triste. Que je vois cette tristesse aussi sur les photos où je suis toute petite (57).

Marguerite Duras | Marie Donnadieu

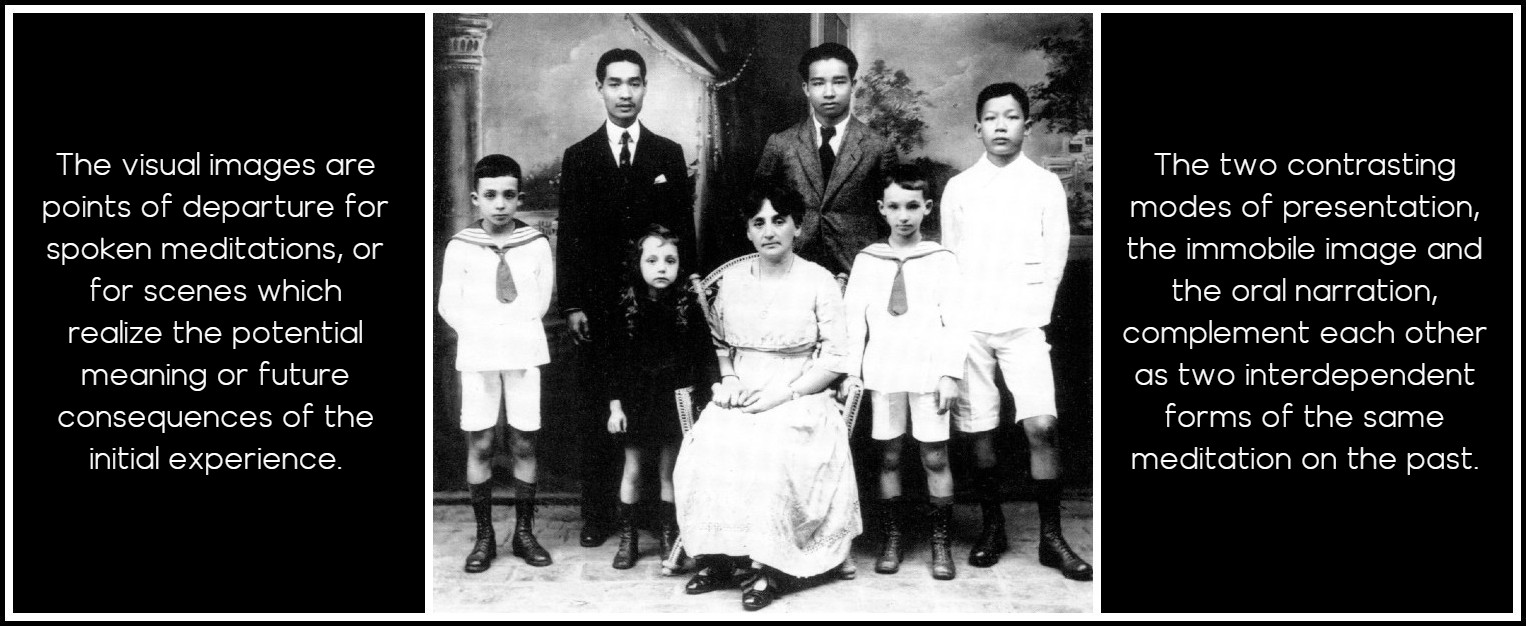

Looking at the photo of her mother, she sees in her the same determination, the same apparently noble and self-effacing devotion to her family and her race which appears in the photos of the rich Vietnamese of the same period: the juxtaposition of esthetic qualities, of the form of the photographs brings out a hidden resemblance in their objects. Even when the image is not embodied in a specific photograph, it serves the same function, enabling the narrator to rediscover and to contemplate her past self: Reste cette image de notre parenté: c’est un repas à Sadec. Nous mangeons tous les trois à la table de la salle à manger (98). Occasionally, the photographic image becomes a cinematic one, the figure begins to move, sound intervenes: Le bruit de la ville est très fort, dans le souvenir il est le son d’un film mis trop haut, qui assourdit (52). Betty Fernandez. Le souvenir des hommes ne se produit jamais dans cet éclairement illuminant qui accompagne celui des femmes. Betty Fernandez. Étrangère elle aussi. Aussitôt le nom prononcé, la voici, elle marche dans une rue de Paris, elle est myope, elle voit trés peu, elle plisse les yeux pour reconnaître tout à fait (82). Throughout the novel, there is a subtle relationship between the immobile, fixed visual image and its developments or consequences, the movements which bring the image to life and which follow the thread of events and meaning through the narrator’s life. The narrative flow of the novel often appears as a monologue, and the narrator occasionally emphasizes the oral quality of her narrative with remarks such as Que je vous dise aussi ce que c’était, comment c’était (94), The visual images are points of departure for spoken meditations, or for scenes which realize the potential meaning or future consequences of the initial experience. The two contrasting modes of presentation, the immobile image and the oral narration, complement each other as two interdependent forms of the same meditation on the past.

Marguerite Duras – Donnadieu Family Portrait – 1920 (father absent)

Thus, the image plays many roles in L’Amant: it is the basic unit of construction of the novel, it is the means by which the narrator explores her past self and its relation to her present, it allows her and the other characters to understand themselves better by contemplating their outward appearance, and it embodies the decisive step towards full personhood which the heroine has taken during this period in her life. These multiple functions of the image help us to understand the importance of the heroine’s precocious choice of writing as her future career. Writing is the essential, the ultimate form of liberation for her: it is the consummation of the movement towards self-creation which has been growing in her during this period. It is the formalization and realization of the power to create images. This is why her mother is jealous of her daughter, why she insists that the daughter study other things, why she finds writing a frivolous occupation: writing is the means to escape, the means by which the heroine will be able to free herself from the misery which entangles the other members of her family. Je lui ai répondu que ce que je voulais avant toute autre chose c’était écrire, rien d’autre que ça, rien. Jalouse [ma mère] est. Pas de réponse, un regard bref aussitôt détourné, le petit haussement d’épaules, inoubliable. Je serai la première à partir. Pour les fils il n’y avait pas de crainte à avoir. Mais celle-ci, un jour, elle le savait, elle partirait, elle arriverait à sortir (31).

Marguerite Duras

Writing appears here as the most effective form of self-creation, an effort to make order and meaning out of the underlying chaos. The images which we read now are the result of a primordial existential choice made long ago by the young narrator, when she realized that writing was the means to gain power over her life and to create a self and a world which would help her to escape the degradation of her familial and material environment. The positive, creative image is thus the absolute condition for the existence of the text we read today. Yet this positive creation is always juxtaposed with an underlying void, a negative force, the impossibility of knowing, attaining others or oneself; and the novel appears as the alternation between these positive and negative forces. While emphasizing the creative function of the images she is recalling and formulating for us, the narrator also makes clear that they exist to evoke things and people who have disappeared. Ils sont morts maintenant, la mère et les deux frères. Pour les souvenirs aussi c’est trop tard. Maintenant je ne sais plus si je les ai aimés. Je les ai quittés. Je n’ai plus dans ma tête le parfum de sa peau ni dans mes yeux la couleur de ses yeux. C’est fini, je ne me souviens plus. C’est pourquoi j’en écris si facile d’elle maintenant, si long, si étiré, elle est devenue écriture courante (38). Writing appears as a compensation for what has been lost; its positive creative capacity compensates for, but also supposes, the absence of the reality it describes.

Marie Donnadieu, Marguerite Duras’ mother

This compensatory function of writing is also true of other forms of images. The visual, photographic images which play such an important role in the novel are in large part compensation for the fundamental impossibility of direct communication and knowledge of others. This is particularly evident in the function of the narrator’s family photographs: Les photos, on les regarde, on ne se regarde pas mais on regarde les photographies, chacun séparément, sans un mot de commentaire, mais on les regarde, on se voit. Ma mère nous fait photographier pour pouvoir nous voir, voir si nous grandissons normalement (115). The photographic image here appears as compensation for an absence, for the inability of the family members to look at each other and to deal with their relationship and their personalities. The photograph thus creates an image of their relationship, to make up for the fact that this relationship is fundamentally blocked; it overcomes the blockage and constitutes an imaginary meeting ground and a means for the individuals to know themselves as well as each other.

Marguerite Duras, Donnadieu Family Portrait, 1918 (father present)

However, the inner reality of the strange love-hate emotions which bind the family together can never be fully expressed: the images by which the narrator tries to exteriorize it appear even now as ineffectual and fragmentary. Cette histoire commune de ruine et de mort échappe encore à tout mon entendement, cachée au plus profond de ma chair, aveugle comme un nouveau-né du premier jour. Elle est le lieu au seuil de quoi le silence commence. Ce qui s’y passe c’est justement le silence, ce lent travail pour toute ma vie. Je suis encore là, devant ces enfants possédés, à la même distance du mystère. Je n’ai jamais écrit, croyant le faire, je n’ai jamais aimé, croyant aimer, je n’ai jamais rien fait qu’attendre devant la porte fermée (35). The creative function of the image is founded on an underlying negativity, the essentially inexpressible nature of the narrator’s inner experience, and perhaps of all inner experience. The external projection of oneself through writing is condemned to remain incomplete because it cannot capture the floating, dynamic, total nature of inner reality. Quelquefois je sais cela: que du moment que ce n’est pas, toutes choses confondues, aller à la vanité et au vent, écrire ce n’est rien. Que du moment que ce n’est pas, chaque fois, toutes choses confondues en une seule par essence inqualifiable, écrire ce n’est rien que publicité (15). Inner reality itself appears as uncertain, slippery, illusory: human identity itself is perhaps founded on an illusion. L’histoire de ma vie n’existe pas. Ça n’existe pas. Il n’y a jamais de centre. Pas de chemin, pas de ligne. Il y a de vastes endroits où l’on fait croire qu’il y avait quelqu’un, ce n’est pas vrai il n’y avait personne (14).

Marguerite Duras, mother Marie, brothers Pierre and Paul, c. 1921

Among these essential images of absence and negativity, there is one form of absence which is truly fundamental, which is in fact the basic generator of the text. The text we read now has taken the place of one absent, central image, one which the narrator in her youth was unable to create because she was as yet unable to detach herself from her situation enough to describe it. The first part of the novel returns again and again to this one central image: the narrator stands alone beside the river, waiting to cross it, and unaware that she is about to have an experience which will change the course of her life. C’est au cours de ce voyage que l’image se serait détachée, qu’elle aurait été enlevée à la somme. Elle aurait pu exister, une photographie aurait pu être prise, comme une autre, ailleurs, dans d’autres circonstances. Mais elle ne l’a pas été. C’est pourquoi, cette image, et il ne pouvait pas en être autrement, elle n’existe pas. Elle a été omise. Elle a été oubliée. Elle n’a pas été détachée, enlevée à la somme. C’est à ce manque d’avoir été faite qu’elle doit sa vertu, celle de représenter un absolu, d’en être justement l’auteur (16-17). The photo was not taken, the image was never concretized, because the meaning of this moment was in the future; thus it is the role of this novel to fill the void. It is the future realization of the absolute potential inherent in the moment of meeting between the narrator and the lover. The text is born out of the dialectical relationship between the visible image of the older narrator, which is presented on the first page, and this absent image of her youthful self.

Marguerite Duras

In the course of the novel, this central relationship between positive and negative forces is developed on many other levels as well. There are a number of characters whose principal role is that of the heroine’s doubles, and the function of the double in the novel is to exteriorize, to project into visible form another one of the narrator’s inner qualities or possibilities. When her younger brother dies, for example, she feels that she herself has also died. The heroine’s friend Hélène Lagonelle contrasts, in her submissiveness and naiveté, with the heroine’s revolt and her early sexual experimentation. Towards the end of the novel, there is a sequence evoking the unhappy love affair between a married lady whom the narrator had glimpsed during her travels and a young man who finally kills himself. The parallel is explicitly drawn between the heroine and the married lady: La même différence sépare la dame et la jeune fille au chapeau plat des autres gens du poste. De même que toutes les deux regardent les longues avenues des fleuves, de même elles sont. Isolées toutes les deux. Seules, des reines. Leur disgrâce va de soi. Toutes deux au discrédit vouées du fait de la nature de ce corps qu’elles ont, caressé par des amants, baisé par leurs bouches, livrées à l’infamie d’une jouissance à en mourir, disent-elles, à en mourir de cette mort mystérieuse des amants sans amour (110- 11). During the sea voyage which ends her affair with the lover, the heroine witnesses the suicide of a young man who throws himself into the sea, and once again she feels an echo in herself, rises as if she were ready to imitate him.

Marguerite Duras with her younger brother Paul, c. 1928 / 1932

The common thread throughout the series of doubles is a certain danger which threatens the heroine, and which has destroyed the other characters. The unhappiness of Héléne Lagonelle, the suicide or death of the young men, the violent passion which sweeps the married lady away: this is the negative underside of the double relationship, the danger against which the heroine is struggling and against which she triumphs. The other figures are projections of this danger, characters who realize the negative destiny which the heroine manages to avoid. The clearest example of this function is the character of the insane woman who follows the heroine as a child, and who inspires numerous nightmares. The narrator’s fear of this woman comes from the fear of contamination; she fears that her own sanity will suffer from contact with the woman. However, the insane woman in her turn is a double of another character, whose insanity is even more frightening for the narrator: her mother. The close relationship between her mother and the woman is stressed, and the woman is accompanied in the heroine’s imagination by a little girl. Moreover, the narrator’s own sanity is called into question by her identification with her mother; after having realized that her mother is insane, she has the terrifying impression of seeing her disappear and be replaced by a kind of vampirish double: L’épouvante venait de ce qu’elle était assise là même où était assise ma mère lorsque la substitution s’était produite, que je savais que personne d’autre n’était là à sa place qu’elle-même, mais que justement cette identité qui n’était remplaçable par aucune autre avait disparu et que j’étais sans aucun moyen de faire qu’elle revienne, qu’elle commence à revenir. Rien ne se proposait plus pour habiter l’image. Je suis devenue folle en pleine raison (105).

Marie Donnadieu, mother of Marguerite Duras

The narrator is horrified by the sudden appearance of the void in her mother’s personality, a void which reveals her mother’s insanity as a form of absence, a negativity at the base of her being. The sudden disappearance of her mother’s identity confirms the heroine’s own fears about the uncertainty of the personality, and thus reflects back upon her own sense of her identity as upon a mirror image, so that her own sanity suddenly begins to vacillate. In this scene, the function of the double clearly illustrates the problem of the personality in the novel, and the relationship between positive image and negative void. The fundamental law which underlies the psychology of the novel is this structure of positive-negative interaction, in which human identity appears as an uneasy alternation between the positive, concrete, creative forces in the personality and an underlying negativity. This essential opposition between positive and negative also governs the spatial and natural symbolism of the book. The position of the heroine at the beginning is very clearly symbolic: she is crossing a river on a ferry boat, and this crossing coincides with a major change in her life. On one side, her childhood, her family and its violent passions; on the other side, adulthood, independence and other forms of violent passion. This symbolism of the passage to adulthood is prolonged, however, in the role of the river and the sea to which it leads. The passage is dangerous, because beneath the boat the river threatens death, destruction, insanity: Dans le courant terrible je regarde le dernier moment de ma vie. Le courant est si fort, il emporterait tout, aussi bien des pierres, une cathédrale, une ville. Il y a une tempête qui souffle à l’intérieur des eaux du fleuve (18).

Marguerite Duras with her mother, Marie Donnadieu

The heroine contemplates the forces of her own mental destruction in the symbolism of the river. This identification of water with violent, dangerous emotions is developed later, when the sea becomes the symbol for sexual ecstasy. Et pleurant il le fait. D’abord il y a la douleur. Et puis après cette douleur est prise à son tour, elle est changée, lentement arrachée, emportée vers la jouissance, embrassée à elle. La mer, sans forme, simplement incomparable (50). And at the end of the novel, the sea is once again associated with danger and death, with the suicide of the young man who jumps overboard. Thus the symbolism of the sea shows the threatening potential of the violent emotions which the heroine has begun to explore as she conquers maturity. Her passage to positive, creative self-realization is continually threatened by negative, dangerous, destructive forces which lurk beneath the surface of her emotions and relationships.

The Steamboat ‘Colombert’ on the Mekong River

The structure of the novel is governed by this symbolism, since the sea appears at the beginning and at the end, in a cyclical pattern. Just as the river had brought the lover to the heroine at the beginning of the novel, the sea takes her away from him at the end. There is a parallel between the physical circumstances: the lover approached the heroine from a distance at the beginning, and at the end he is condemned to contemplate her from a distance as her ship pulls away. The boat trip which begins the novel is one kind of passage, and the trip which ends it is another; the parallel shows the evolution of the heroine, and her movement towards another destiny. This movement which will continue the heroine’s progress toward self-creation is once again accompanied by a necessary element of destruction: the end of her affair with the Chinese lover. And this idea is once again expressed by aquatic symbolism: Elle n’avait pas été sûre tout à coup de ne pas l’avoir aimé d’un amour qu’elle n’avait pas vu parce qu’il s’était perdu dans l’histoire comme l’eau dans le sable (138).

Photo: Polina Kuzovkova, Unsplash

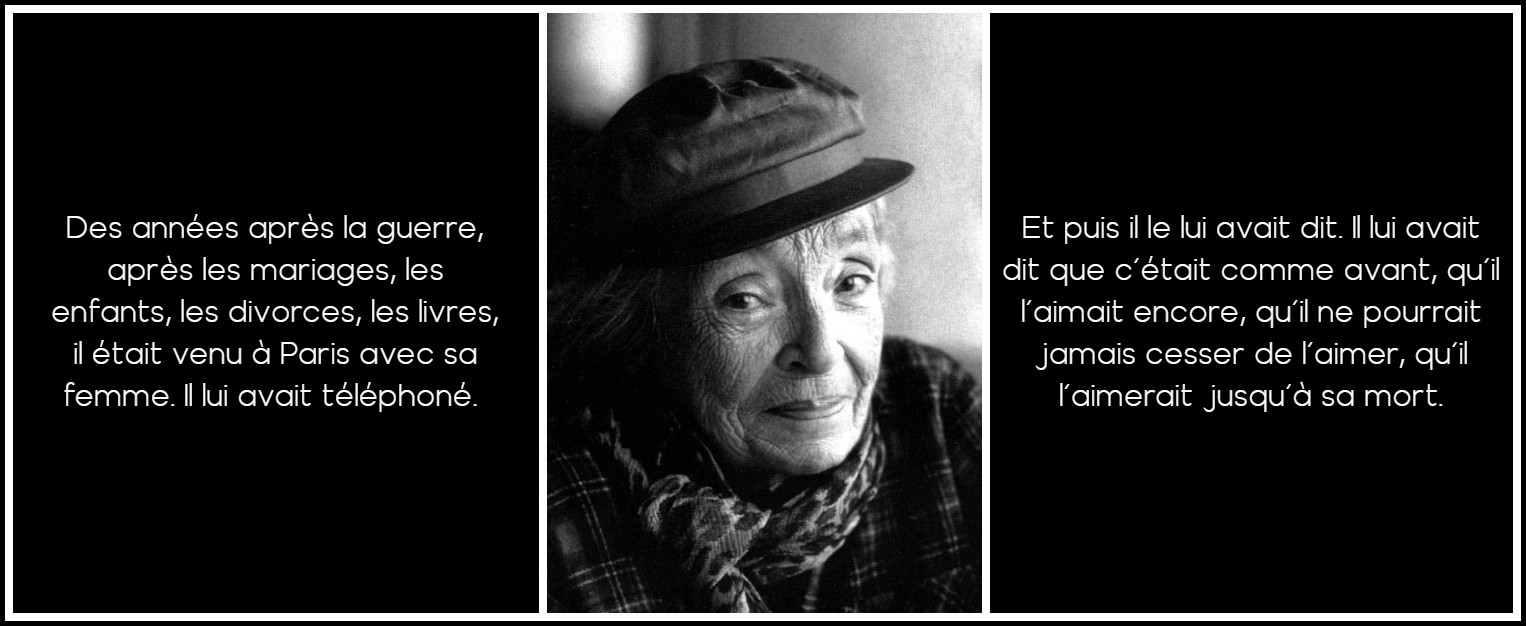

There are other significant parallels between the beginning and the end of the novel as well. The novel ends with a telephone call from the Chinese lover, which brings us close to the present, but also returns to the very first incident of the book and the comment from the narrator’s anonymous admirer. Both are expressions of love or admiration from men who appear suddenly, from out of a vague, public context. The Chinese lover’s words complete the comments of the admirer, showing us the full circle of the novel’s events. However, there is one important difference between the two incidents. The unknown admirer sees the narrator’s face and comments on it, while the lover does not see her. He is thus unable to witness time’s effects on the heroine, as the first man did; in fact, time has not passed for him, his voice is a voice out of the past: Des années après la guerre, après les mariages, les enfants, les divorces, les livres, il était venu à Paris avec sa femme. Il lui avait téléphoné. Et puis il le lui avait dit. Il lui avait dit que c’était comme avant, qu’il l’aimait encore, qu’il ne pourrait jamais cesser de l’aimer, qu’il l’aimerait jusqu’à sa mort (141-2).

Marguerite Duras

In this last scene, there is no more visible image as there was at the beginning; the two communicate at a distance, and this distance expresses a fundamental absence which appears now to have been an essential part of their love from the very beginning. Throughout the novel, in fact, the heroine is unable to say whether she loves the Chinese man or not, preferring to brush aside questions with easy answers about his money. In the passage quoted above, the heroine is unsure whether in fact she did love him without realizing it. And when she decides to break up their relationship, she gives no reasons. Alors je lui ai dit que j’étais de l’avis de son père. Que je refusais de rester avec lui. Je n’ai pas donné de raisons (103). This refusal to explain, to put into words, this later doubt about their true relationship show that it, too, like the other forms of intense relationship in the novel, is an absence, an unknowable abyss. But in this context, the writing of the novel itself takes on a deeper significance. The novel, dedicated to the lover through its title, is a way to make up for what was unsaid. Through its creation, the narrator compensates for the domination of the negative forces which finally destroyed the love affair. Thus, the work represents a form of tribute to the lover; but more importantly, it is the final, most profound form of image, a way to bridge the abyss and to realize the positive potential of a complex experience.

Marguerite Duras, L’Amant, Les Éditions de Minuit, 1984

NINA HELLERSTEIN: BOOK

MYTHE ET STRUCTURE DANS LES ‘CINQ GRANDES ODES’ DE PAUL CLAUDEL

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments