‘Wild Desire and Quenchless Will’

SEX AND DESIRE IN WUTHERING HEIGHTS – PART 2

Susan Ostrov Weisser

Posted by kind permission of Susan Ostrov Weisser, Professor Emerita of English Literature, Adelphi University, New York

From Susan Ostrov Weisser, ‘Wild Desire and Quenchless Will: Wuthering Heights’ in A ‘Craving Vacancy’: Women and Sexual Love in the British Novel, 1740-1880

(New York: New York University Press, 1997) 102-113

In addition to this scholarly work, Susan Ostrov Weisser has also authored, for the general reader, Loveland: A Memoir of Romance and Fiction and The Glass Slipper: Women and Love Stories.

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. READ PART 1 FIRST.

Fernand Khnopff, Étude anglaise, 1882

While Catherine described her attraction to Edgar as another kind of romantic love in the confession scene to Nelly, it is also clearly placed by her in a constellation of social values associated with courtship. The formula for feminine success of a certain kind is a familiar one to any reader of nineteenth-century novels: access to money, respectability and the status of membership in a valued social class, at the price of the moderation of desire. But Brontë has Nelly, with a shrewd irony lost on a Catherine absorbed in feeling, question the univocal simplicity of this definition of heroineship from the bourgeois novel: Well, that settles it—if you have only to do with the present, marry Mr. Linton. You will escape from a disorderly, comfortless home into a wealthy respectable one; and you love Edgar, and Edgar loves you. All seems smooth and easy—where is the obstacle? The ‘obstacle’ is a ‘secret’ which Catherine, in the same scene, promises to explain, only to qualify her promise by adding, ‘I can’t do it distinctly—but I’ll give you a feeling of how I feel’. She then refers to a dream, somehow meant to be explanatory, which Nelly refuses to permit her to tell—’I won’t hear it, I won’t hear it!’ she cries—and the reader never does hear either that dream or the explanation.

Philip Alexius de Laszló, Countess Fitzwilliam, 1911

What we are given ‘instead’ is Catherine’s metaphorically significant dream of her discovery that heaven is not her true home, but even this is very much a displacement rather than a direct articulation of her meaning; we are given no indication that either Nelly nor Catherine herself can make it out as a disclosure of Catherine’s selfhood. Catherine’s dream of being expelled from Heaven thematically fits the frames surrounding the novel—Christian and irreligious, realist and supernatural, masculine and feminine—without being clarified by them. It is the untellable which must constitute the essential for Catherine, as both language and social practices constrain her, proving inadequate to identity. In Wuthering Heights the untellable is an unspeakable sexuality. Catherine’s feelings for Heathcliff are impossible to convey through the medium of language, because they are as complex and contradictory as sexuality itself. It is not so much that such a love is possible only in childhood, before the development of adult sexuality, as several critics have suggested, as that the childhood intimacy shared by the two is itself a metaphorical representation of the Brontëan idea of a sexuality which is ‘unselfconscious’ in the literal way of having no consciousness of boundaries between selves, or (what amounts to the same thing) of having no vocabulary to talk about the separation of selves.

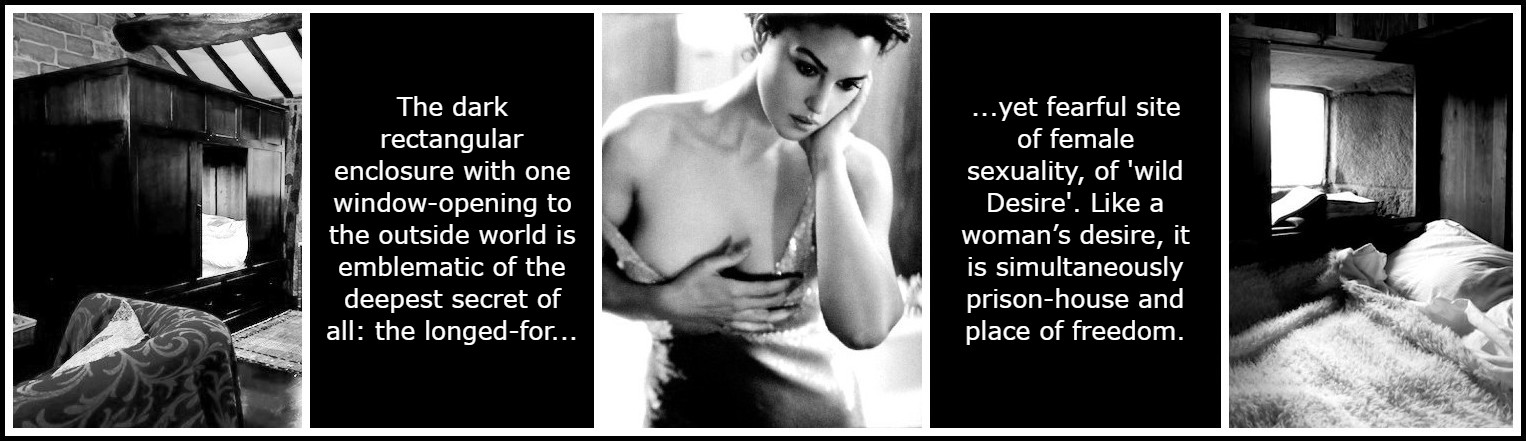

Edward Burne-Jones, Lady Frances Balfour, 1880 | Paolo Roversi, Nadja Auermann, 1992

When Catherine cries in anguish, ‘Oh, if I were but in my bed in the old house!’ the recurrent image of that bed, pervading the novel from the scene of Lockwood’s dream to its close in Heathcliff’s deliberate choice of it as his death-place, unites the themes of childhood, sexuality and death in one densely wrought symbol. The old-fashioned, oak-panelled bed shares in the gathering emotional force of Wuthering Heights itself as a sacred place. As an enclosed space at the far end of a bedroom located deep in the interior of the house, it appears to be its inmost sanctuary. Carefully described as bordered by sliding panels on one side and a window on the other, it is clearly associated with the sympathetic intimacy of Catherine and Heathcliff’s childhood bond, before the adult sensibility separated the two into selves, but it is also something more. A boxlike structure, it is like a coffin with exits for a kind of movable death, the sort that will allow Catherine’s ghost to attempt to enter the bedchamber window, or her remains to dissolve with Heathcliff’s after he has ‘struck one side of the coffin loose’. And last, this dark rectangular enclosure with one window-opening to the outside world is emblematic of the deepest secret of all: the longed-for yet fearful site of female sexuality, of ‘wild Desire’. Like a woman’s desire, it is simultaneously prison-house and place of freedom.

The Box Bed, Ponden Hall, Haworth | Dominique Issermann, Monica Bellucci, 2003 | The Box Bed, Ponden Hall, Haworth

Immediately following Cathy’s recounting her memory, she wishes aloud that she were ‘a girl again, half savage and hardy, and free’, and, sure that she should ‘be myself were I once among the heather on those hills’, she urges Nelly to ‘Open the window again, fasten it open!’ Nelly refuses, saying, ‘I won’t give you your death of cold’; to which Catherine swiftly returns, ‘You won’t give me a chance of life, you mean’. Like the incursion of sexuality, the opening out of the window to the world of childhood implies both death and the chance of life at once. Though Catherine has now located her lost ‘real’ self in the authenticity of childhood, she cannot see how to unite that selfhood, which is contained in her relation to Heathcliff, with the body of the Lady which is no longer ‘herself’. It seems that the only recourse is to renounce that physical shell along with the role she rejects. Now slipping into delirium, she speaks aloud to Heathcliff, as she dares him to defy their separation by a union in death, the road home to a perpetual childhood which will evade her present problem: ‘But Heathcliff, if I dare you now, will you venture? If you do, I’ll keep you. I’ll not lie there by myself: they may bury me twelve feet deep and throw the church down over me; but I won’t rest till you are with me, I never will!’ Though Catherine now recognizes the ‘impracticability’ of their separation, the necessity of some undefined quality of selfhood which Heathcliff brings to her, she envisages a ‘spiritual’ joining, literally a union of ghostly spirits, much as at her decision to marry Edgar she had planned on a purely social relation between them. Like the spiritual adulterers of medieval courtly love, she now believes she and Heathcliff will enter a space ‘beyond’ sexuality.

Philip Alexius de Laszló, Countess Fitzwilliam, 1911 | Edward Burne-Jones, Antonia, 1877

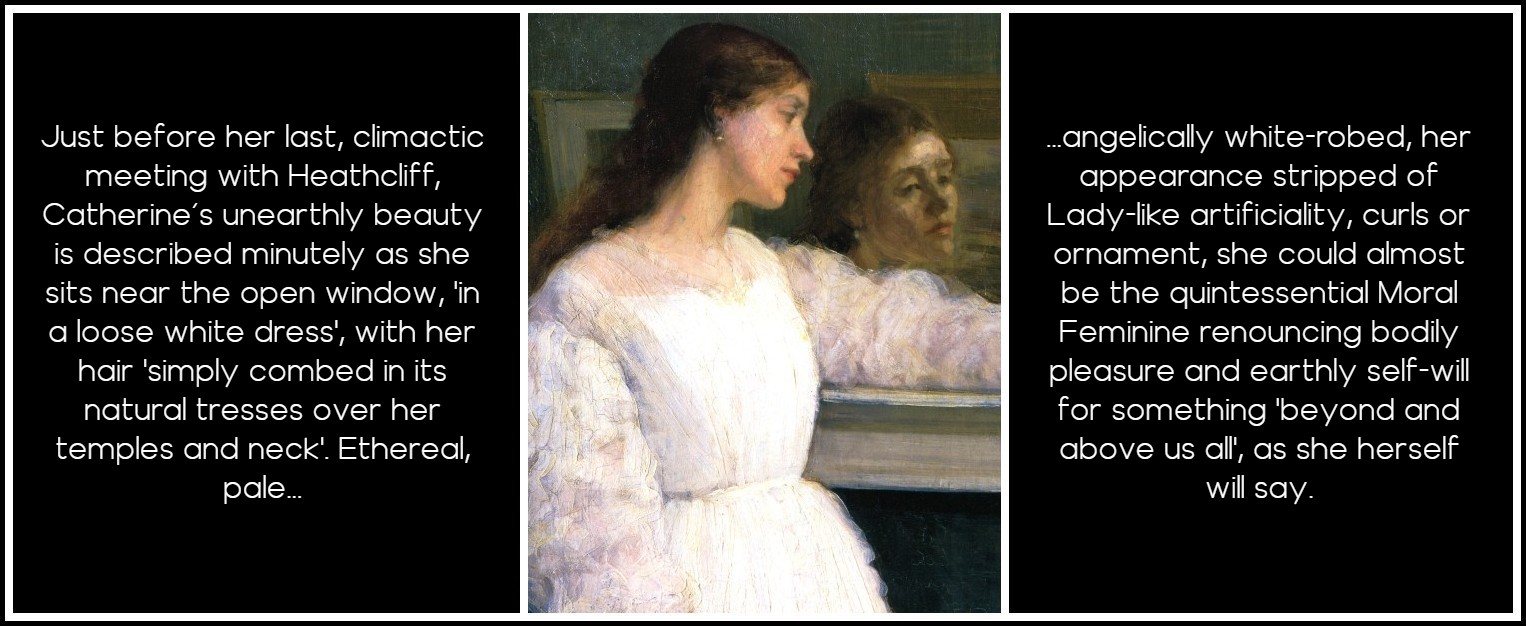

When we next see Catherine it is two months later. We now learn for the first time that Cathy is and has been pregnant; moreover, she is recovering from ‘what was denominated a brain fever’. Just before her last, climactic meeting with Heathcliff, Catherine’s unearthly beauty is described minutely as she sits near the open window, ‘in a loose white dress’, with her hair ‘simply combed in its natural tresses over her temples and neck’. Ethereal, pale, angelically white-robed, her appearance stripped of Lady-like artificiality, curls or ornament, she could almost be the quintessential Moral Feminine renouncing bodily pleasure and earthly self-will for something ‘beyond and above us all’, as she herself will say. As Nelly describes her: The flash of her eyes had been succeeded by a dreamy and melancholy softness: they no longer gave the impression of looking at the objects around her; they appeared always to gaze beyond, and far beyond—you would have said out of this world. To recall the literary convention that is being invoked, we have only to compare this with Richardson’s description of Clarissa as Belford finds her awaiting her death: We beheld the lady in a charming attitude. Dressed, as I told you before, in her virgin white, she was sitting in her elbow-chair. One faded cheek rested upon the good woman’s bosom, the kindly warmth of which had overspread it with a faint but charming flush; the other paler and hollow, as if already iced over by death. Her hands, white as the lily, with her meandering veins more transparently blue than ever I had seen even hers; her aspect was sweetly calm and serene.

James McNeill Whistler, Symphony in White, No. 2, 1864

Yet it should be clear by this time that it is Emily Brontë’s method to prime us for a conventional expectation, only to demolish it to better effect. For in the scene that follows, it is Cathy’s very state of extremity, the madness, pregnancy and nearness to death—all invitations to sentimental writing about female fragility and/or passivity—which induces a defiant atmosphere of lawlessness in which she can make her final leap into a state which Brontë allows for only at the very point of death. At the very end of Catherine Earnshaw’s life, the consciousness of Desire, her sexual love for Heathcliff, is stained with a heightened vulnerability to death, like wine through water. The scene of Catherine’s last reunion with Heathcliff is a melodramatic but carefully orchestrated dialogic struggle between the conflicting views of the two lovers on the validity of sexual love in shaping selfhood. Who has killed Catherine? Catherine herself suggests at first that it was Edgar, by refusing to allow her to choose both Ladyhood and her sexual self at once. Or was it Heathcliff, who would not permit the repression of her sexuality? No, says Heathcliff, ‘You, of your own will, did it’.

Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Head of a Woman, 1875 | Photo: Hans Feurer, 1987

We have been prepared for this all-important struggle by being left deliberately unprepared. As the intensity of the conflict between Cathy and Heathcliff began to mount, we have hardly noticed the absence of any articulation of Cathy’s feelings for him. Heathcliff is given the scene with Nelly immediately after his marriage in which he describes his intentions and justifies them by calling Cathy an ‘oak in a flower-pot’ but all we have from Catherine is her joy at his return and her desire for some kind of possession. Between these there are no enlightening words to a confidante comparable to her early confession scene, no journal entries, no aid to inform us of Cathy’s self-knowledge or her state of mind. Catherine’s sexual response to Heathcliff is a gap in the text, a mystery that has been deliberately cultivated. Before Heathcliff’s last visit, Catherine has been silent and passive in the extreme, as becomes dying femininity. She does not speak as she sits dreamily by the window; she seems unable to read Heathcliff’s letter asking for an interview by herself, or even to reply: ‘She merely pointed to the name, and gazed at me with mournful and questioning eagerness’, as Nelly says. Heathcliff enters the room and kneels down on one knee to hold her in the traditional stance of courtly adoration, much as Clarissa’s long-awaited cousin Morden ‘folded the angel in his arms as she sat, dropping down on one knee’. His first words, ‘Oh, Cathy! Oh my life! how can I bear it’, echoing Lovelace’s ‘An eternal separation! O God! O God! How can I bear that thought?’ should appropriately evoke an answering speech of physical renunciation; Clarissa’s ‘He will not let me die decently’, or ‘God’s will be done’, will do for a model.

Steve-Gullick, Peter Perrett, 2017 | Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, 1987

Yet in an abrupt and shocking reversal, the moment Heathcliff has her grasped in his arms, Catherine resumes her former mastery, berating him cruelly as though his mere touch is enough to bring to life the impetuous strong will she showed formerly. So far from acting the withdrawing angel, the resistant maiden or well-bred Lady, Nelly tells us plainly that ‘my mistress had kissed him first’. Though she is the aggressor in this agonized interchange—she keeps Heathcliff in a stance of submission momentarily by ‘seizing his hair’—she is in fact surrendering to his demand for sexual love. When she cannot control him, Catherine retreats into her former longing for death. Her body, she muses, is a ‘shattered prison’, from which she is ‘wearying to escape into that glorious world, and to be always there.’ As pure spirit, Catherine will not only be forever ‘beyond and above us all’, but out of the reach of the vicissitudes of her human sexual nature. She would be, in other words, a Clarissa, who affirmed that ‘she should be a happy creature as soon as she could be divested of these rags of mortality’.

Alain Robbe-Grillet, La Belle Captive, Gabrielle Lazure

In the delirium of her mad episode, Catherine showed her knowledge that Heathcliff would ‘rather I’d come to him’, i.e. embody their ‘we-ness’ in the leap to a human sexual relation, rather than in death, the way through the kirkyard. Now, as tension between them mounts to fearful climax, ‘An instant they held asunder; and then how they met I hardly saw, but Catherine made a spring, and he caught her, and they were locked in an embrace from which I thought my mistress would never be released alive.’ The sexual feelings released in this spring seem strong enough to shatter Catherine’s mental frame: ‘To my eyes,’ says Nelly, ‘she seemed directly insensible’. This ‘spring’ is the inverse of that ‘spring from the window’ with which Catherine had threatened Edgar if he mentioned Heathcliff’s name; it is not an attempt to bridge over ‘the abyss where I grovelled’, Catherine’s consciousness of the empty universe and the vacancy of her selfhood, by an avoidance of irresolvable conflict. It is a daring—and literally dangerous—leap into the unknown, a momentary immersion in sexual experience which is, too late, her ‘chance of life’.

Rodin, The Kiss, 1898

Desire and Will unite at last in Catherine’s last gesture, made with ‘mad resolution’ in the anarchic name of love: her refusal to allow Heathcliff to leave on Edgar’s arrival, though Nelly pleads ‘for Heaven’s sake’. In Wuthering Heights we are never allowed to forget that the energy generated by the spring into full female sexuality is not a warm glow, but a self-consuming inferno. Catherine never regains consciousness from the swoon that follows their last embrace, and her life ends that night. One might say that Catherine dies both from sexual desire and in order to forestall its physical consummation, leaving the reader suspended at that heightened climactic moment in which both the joyous Heaven of fulfilled Desire and the Hell of subsequent deprivation are always deferred. Catherine died, Nelly tells Heathcliff, ‘like a child reviving’, immersed in the ‘glorious world’ of eternal childhood, which Nelly pictures as unending prelapsarian innocence. Once again we are returned to the image of Catherine as the womanly angel in Nelly’s observation of her death as ‘perfect peace’: ‘Her brow smooth, her lids dosed, her lips wearing the expression of a smile. No angel in heaven could be more beautiful than she appeared’. We need only turn to Richardson’s description of Clarissa at the point of expiring to see the very type of will-less feminine passivity that is being invoked: ‘Bless – bless – bless you all…’ And with these words, the last but half-pronounced, expired: such a smile, such a charming serenity overspreading her sweet face at the instant, as seemed to manifest her eternal happiness already begun.

Photo: Javier Valhenrat, 2009

Yet as we know, in death Catherine is neither silenced nor subdued: if anything, she is more quenchless than ever, seeking to exercise her power over Heathcliff as she dominates the text—through her absence. Withholding her presence from Heathcliff, as she drove him wild in life by withholding her sexuality, she continues to haunt this novel as a desirous spirit, a figment or fragment of her self—that is, of her embodied self. We are left at the end with a paradox: the spirit Catherine may have achieved selfhood without social or gender boundaries, the perfect state of being as a ‘we’, by subsuming Heathcliff into her own state of ghostliness, but she is once again lacking, since she is no longer a living woman when she achieves this consummation. Like Heathcliff wanting to catch one more glimpse, readers and critics continually resurrect her by recasting her conceptually, recreating her for themselves. In attempting to ‘understand’ and place her in a larger context than her own story, we are teased, again like Heathcliff, by the partial satisfaction of our expectations in the process of reading the text of Wuthering Heights. Thus the visionary possibilities of the (possibly) supernatural realm textually undermine the realism of Nelly’s domestic pieties and ethical certainties even in the second half of the novel, in which the narrative of another Catherine and her two loves seems to reduce the original story of sexual love to a project of revision rather than vision.

Fernand Khnopff, The Faerie Queen, 1892 | Fernand Khnopff, Mon cœur pleure d’autrefois, 1889

Most of all, the literary convention that traditionally enclosed the heroine in a certain kind of sexual narrative—one with an ending that transformed sexuality into the story of courtship and marriage—is found wanting here, and literally burst apart, splitting the story in two. The second half of the novel, depicting Catherine’s daughter and her courtships, does satisfy this particular literary expectation, as we all know, but because the first Catherine has passed beyond the social/physical world, this story is too late for her, as well as besides the point in the timeless world she is said to inhabit. The structure of the second half of the novel, in which the relationships of the younger generation parallel the first on a smaller and less intensely emotional plane which at times approaches caricature, is too well known to require detailed repetition here. When we have been taxed and drained by outrageous reversals of expectation, and while our own emotional involvement with the proponents of sexual love is at its height, the novel suddenly draws a breath and begins again. In doing so, it slowly rights itself back to the convention that was earlier stood on its head, until the rebels are rebelled against, and the values of the questioners questioned.

Julie Delance-Feurgard, Le mariage, 1884

Whereas the elder Catherine began in passion and rebellion, but was attracted in the sexual crisis of adolescence to the rewards of Ladyhood, young Cathy is born the ‘little lady’, with the ‘petted will’ of one indulged and protected, yet she is increasingly attracted to the risky possibilities of experience. In an early exchange with Nelly, Cathy wishes repeatedly to visit the ‘golden rocks’ of Penistone Craggs, ‘high and steep’, which Nelly tells her she is not old enough to climb. These ‘bare masses of stone’, as Nelly calls them in the same conversation, the Penis-Stone, in effect, represent a romanticized view of male sexuality—or, to put it another way, Penistone Craggs are a representation of male sexuality enhanced by adolescent romanticization. Young Cathy is equally drawn towards an exploration of her own female sexuality, as embodied in the image of the cave near the crag, an analogue in nature of her mother’s enclosed bed: One of the maids mentioning the Fairy cave, quite turned her head with a desire to fulfil this project; she teased Mr. Linton about it; and he promised she should have the journey when she got older. Young Cathy is inevitably drawn back by her restless, as yet unnamed longings to Wuthering Heights, to which she naughtily runs away as a child, as her mother had run away at the age of twelve from nature to Thrushcross Grange. Desire has been awakened by a perceived lack, and we are, narratively speaking, on an odd backward journey towards the original Will and Desire located in the text at the site of Wuthering Heights.

Fernand Khnopff, Portrait of Gabrielle Braun, 1886 | Ponden Kirk – Penistone Craggs (Photo: Tom Howard)

At the Heights, Cathy meets Hareton for the first time, a gentleman’s son in the guise of a servant (as Heathcliff is the former servant of the family now in the guise of a gentleman). Hareton, at Cathy’s request, ‘opened the mysteries of the Fairy cave’. By the close of the novel, Hareton will ‘show her the way’, as she asks him at one point, to the evocative meanings of the Cave and the Crag, those sexual constructions which are visited in tandem. But Cathy is not yet ready for this climb, as Hareton is not ready for her: thus, she refuses to acknowledge her blood relation to him at this first meeting. In the term ‘blood relation’—they are first cousins—we may see again the multivalent meanings that attached to the ‘incestuous’ relation of the first Catherine and Heathcliff. Cathy’s distressed assertion of her superiority of rank and ‘culture’ at this encounter is an inverted parallel to Catherine’s painful rejection of Heathcliff’s dirtiness after her visit to Thrushcross Grange. Significantly, this conversation between Cathy and Hareton is in the same tone of comic misunderstanding with which the novel began. Most importantly, the focus here is on the absurdity of the second Cathy’s desires, which need correction and moderation, rather than on the tragic pain inherent in the oppressive contradictions of female sexuality itself.

Top Withens, Haworth, West Yorkshire | Photo: Tom Howard

The same broad touch of caricature marks the character of Linton, the son of Heathcliff and Isabella, whom Cathy begins to visit at Wuthering Heights when she is sixteen, just as her mother was visited there by Edgar in her adolescence. Linton, ‘more of a lass than a lad’, as is intimated several times, is a parody, not only obviously of Edgar’s own effeteness, but of the stereotypical passivity and manoeuvres of the Lady. Linton ‘giggles’, ‘titters’, weeps, sulks, pouts, worries endlessly about his food and his comforts, and finally fades in a decline as delicate as that of any fragile Lady. Cathy’s relation to him is what Heathcliff and Catherine’s is often said to be: truly asexual. Though she fancies herself in love, her affection never extends much beyond ‘stroking his curls, and kissing his cheek, and offering him tea in her saucer, like a baby’, or later, ‘wishing you were my brother’. Entirely self-absorbed, Linton sees Cathy as the Lady sees a potential husband, the source of amusements, material comforts and protection, physical and economic, from the world’s abuse and hardships. In our last glimpse of him before death he is stretched on the settle, ‘sole tenant, sucking a sugar-candy, and pursuing Nelly’s movements with apathetic eyes’; he could be the childish and spoiled young lady in any number of Victorian novels, including the self-indulgent, weak and useless Georgiana, asleep on a sofa in Jane Eyre. It is as though Cathy were set to grotesquely expiating in her ‘love’ for Linton both her mother’s ambition to profess the role of Lady and the false asexuality of her desired relation to Heathcliff. Fittingly, Linton dies before the marriage with Cathy is consummated; indeed, one feels that it never could have been consummated. Like any conventional romance, it is a relation in name only, and incapable of providing a true Home.

Thomas Gainsborough, Giovanna Baccelli, 1782 | John Closterman, Children of John Taylor, 1696 (detail)

But Cathy, unlike her mother, is allowed to marry twice; that is, she is proven educable, transformable from an essential identity into a feminine self. As Heathcliff had predicted, on forcing her back to Wuthering Heights after her father’s death, ‘You shall be sorry to be yourself presently’. The implication of her malleability is that Cathy must face the death of her girlhood self before assuming full life as a woman who is also a Lady—a good Lady, which is to say, an exemplar of ‘real’ femininity, in the way Victorian society fashioned that paradigm. Nevertheless, a vivid note is struck by Brontë even here, where so many critics, feminist and otherwise, have expressed disappointment in the novel: Cathy and Hareton, bent together over a book, are said to be ‘animated with the eager interest of children; for though he was twenty-three and she eighteen’—she is the same age, one notes, as her mother when the latter renounced her childhood love in marrying Edgar—‘each had so much of novelty to feel and learn, that neither experienced, nor evinced the sentiments of sober disenchanted maturity’. The two lovers are, in other words, recapturing the state of ‘eager children’ lost by the two who began the story.

Godfrey Kneller, Lady Mary Berkeley, 1700

When, having offended Hareton, Cathy kisses him first, her ‘gentle kiss’ is a naively childlike expression of her sexual will, contrasting sharply with Catherine and Heathcliff’s tumultuous last reunion, when she (the first Catherine) also was said to have ‘kissed him first’. The intimate relation Cathy and Hareton achieve, that of ‘sworn allies’, seems intended as a triumphant recapturing of the ‘we-ness’ forged in rebellion by Catherine and Heathcliff, an absorption of both childhood and sexuality within the conventional vocabulary of romantic love. It is difficult, in this second half of the novel, but not entirely impossible, to be a childlike adult, i.e. to grow up by journeying backwards into a mode of sexuality that does not entirely abrogate an essential, desiring female self.

Peter Lely, Study for a Portrait of a Woman, 1675 | Thomas Gainsborough, The Painter’s Daughter, Mary, 1850

But Wuthering Heights, we remember, does not end with a scene of domestic happiness, nor can it, as a text, be enclosed by a single voice or frame. As Heathcliff becomes more and more conscious of Catherine’s spiritual presence after Cathy and Hareton’s rapprochement, the sexual tension in the novel builds once more to nearly its former state. Heathcliff is described as shivering ‘as a tight-stretched cord vibrates’, with ‘a strong thrilling’. To Nelly, his joy is ‘unnatural’ as he rushes towards death and a kind of sexual consummation which requires his anguished renunciation of the will to live. In a most evocative image, Heathcliff himself declares that living in such a state is ‘like bending back a stiff spring’; the more that this spring, the mechanism of his desire, is bent or warped or forced back, the greater the force with which it will fly to his ‘one universal idea’, the return to a state of ‘we-ness’ with Catherine. Heathcliff is about to spring towards union, a kind of metaphor combining death and sexuality, to surrender, as Catherine did, to being ‘devoured’ by a stronger will: ‘I am swallowed’, he says, ‘in the anticipation of its fulfilment’.

Arnold Böcklin, The Honeymoon, 1890

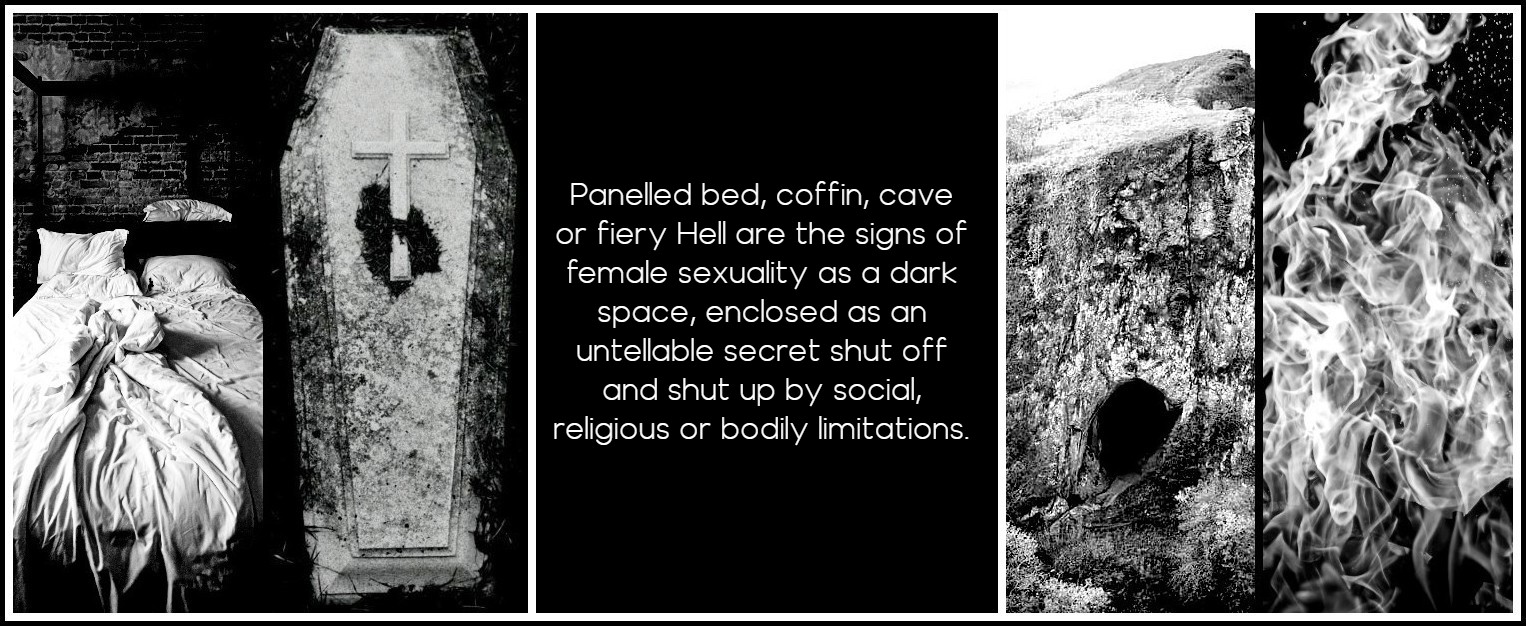

The famous ending is the suggestion of a haunting, not a union of two bodies. Like the interiority of the Fairy cave fascinating to both Catherines, the lure of Catherine’s and Heathcliff’s spirits, last seen ‘under t’ Nab’, which haunts the novel’s conclusion, invokes the unresolved nature of sexuality, with its uneasy relation between a ‘quenchless’, irreducible Will and the necessity of submitting Desire to social convention. Though in Wuthering Heights the code of identity is inscribed onto a revisionary story of sexual love, the refusal of closure is the novel’s resistance to disclosure of the female self. Panelled bed, coffin, cave or fiery Hell are the signs of female sexuality as a dark space, enclosed as an untellable secret shut off and shut up by social, religious or bodily limitations. Both definition and articulation disrupt the unspeakable force of Desire which is the seed of a Brontëan female identity, and at the close of the novel the first Catherine continues to resist this process as much as the second submits to transformation.

Unsplash photos: Dmitriy Frantsev | Sirena Velena | ? | Tobias Rademacher

Thus Wuthering Heights is emphatically about both Catherines, Catherine younger and older, Catherine as body and spirit, Catherine as natural and as socially mediated figure, Catherine herself and Catherine through Heathcliff, Catherine speakable and Catherine unspeakable: a seemingly endless multiplicity of Catherines. It is also about Woman by herself and at one with man, gendered and double-gendered, its text containing a single, essential definition of femaleness and yet also withstanding containment in its plural, relativistic tellings. Similarly, though Wuthering Heights appears in our hands as a whole text, it remains open to us in one sense as a series of fragmented, singular and contradictory stories, never satisfying our thirst for narrative completion. An entirely unquenchable author herself, Emily Brontë explored the quenchless force of female sexuality in a form that defied convention and enclosure: the tragic space of Desire, Will and death, never rendered fully ‘understandable’ to the reader—nor to the novel’s narrators, who seem to silence the ‘real’ story, as convention suppresses the female sexual self.

Emily Brontë – Wuthering Heights

The first half of the essay is to be found in Part 1 (see image-link under ‘Related Posts’ below)

SUSAN OSTROV: THREE BOOKS

LOVELAND: A MEMOIR OF ROMANCE AND FICTION

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

A ‘CRAVING VACANCY’: WOMEN & SEXUAL LOVE IN THE BRITISH NOVEL

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

THE GLASS SLIPPER: WOMEN AND LOVE STORIES

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments