Sprague’s Poems II

Poems from ‘Mara, Marietta’ | Poet & Novelist: Poetry, Fiction and the Private Self

Sprague

POEMS FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

PART TWO

Richard Jonathan

ALL POEMS © 2024 RICHARD JONATHAN. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

INTRODUCTION COMMON TO SPRAGUE’S POEMS I, II & III

In a stream-of-consciousness sequence in my novel, Mara, Marietta, the following dialogue flows through Sprague’s (the hero’s) mind: ‘Who speaks when I speak? To whom am I speaking when I speak? To submit to language is to forget: Poetry occurs where language gives way. What is the task of poetry? To push toward the origin of language. Memory and devotion, invocation and address: the spirit and the word.’1 Sprague is a poet and a rock song lyricist. It is entirely natural, then, that he resorts to poetry (and lyric-writing) whenever he is reliving, during the process of writing—he is the narrator of the novel that turns out to be a long love letter to the heroine, Marietta—emotions and thoughts that overwhelm discursive language. Note that the poems are presented in the sequence in which they occur in the novel. They may, therefore, serve as markers on the map of Sprague’s relationship with Marietta. They cannot, however, trace its chronology: Marietta, Marietta is governed by the fluid time inherent in the process of memory, a time akin to dream-time. Finally, note that in the novel the ‘titles’ of the poems are not given: they were ‘purpose-built’ here for ease of reference. The poems intermingle with the prose as Sprague passes organically from one mode to the other. As Mara, Marietta aims to sustain a heightened sense of being from the first word to the last, the reader will therefore find no sharp distinction between poetry and prose, but rather a continuum.

1 – These thoughts echo those of Philippe Lacoue-Labarthe in his book, Poetry as Experience, trans. Andrea Tarnowski (Stanford University Press, 1999).

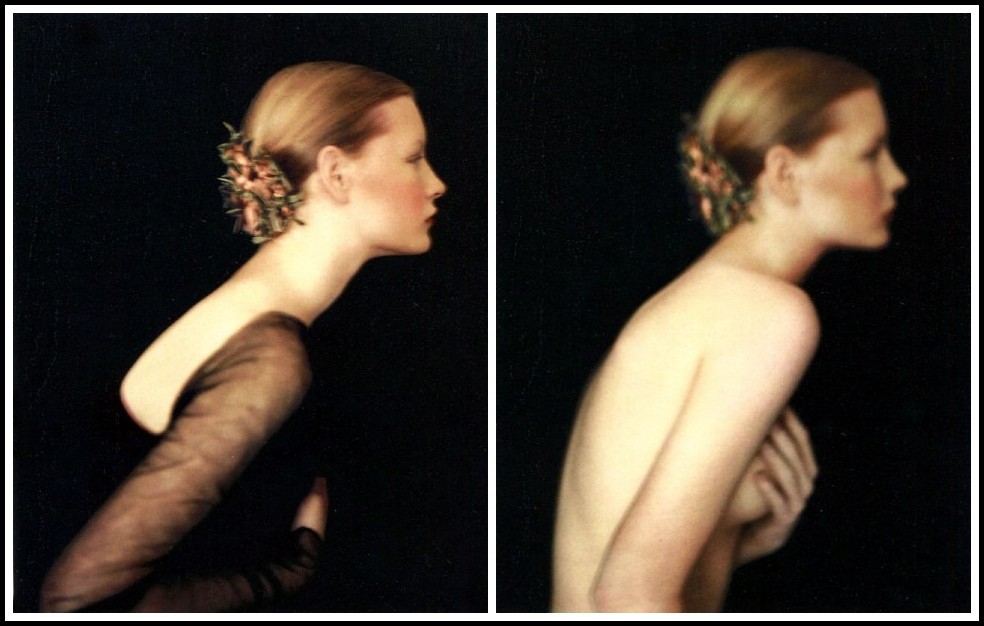

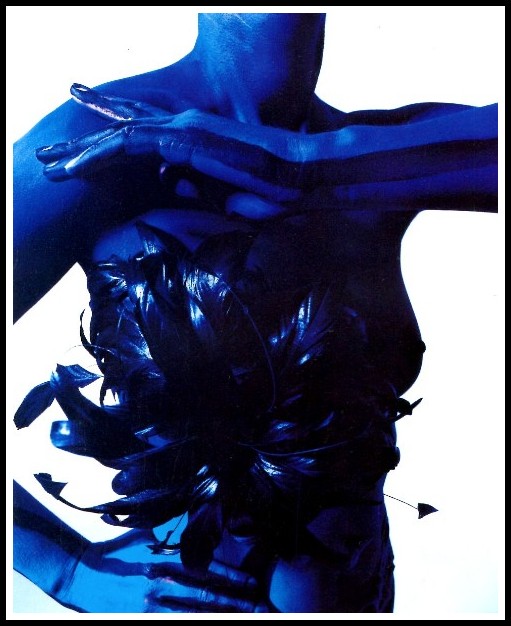

Paolo Roversi, Nadja Auermann, 1992

1. ADRIFT

The coin of Tyche, the stretched string;

Pattern, order and chaos:

Between contingency and necessity

Between reason and the absurd

I find myself adrift.

The gathering of thought, the mnemonics of pain;

Memory, forgetting and healing:

Between oblivion and presence

Between obsession and lucidity

I find myself adrift.

The sovereignty of the self, the question of self-concealment;

Love, knowledge and delusion:

Between action and introspection

Between melancholy and exuberance

It find myself adrift.

Marietta, what I am to do?

Won’t you help me,

Help me to live without you?

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

2. UNSPOKEN

The night delivered

New names for love,

The word itself unspoken;

Into the frenzy of desire,

The infusion of devotion.

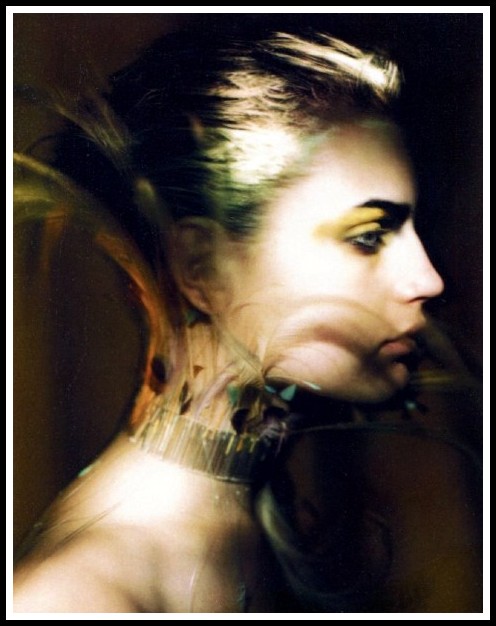

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

3. SPANISH GUITAR

I bought you a guitar for your birthday,

A Spanish nylon string.

Why’d you do that? you asked me.

I replied, Cause you love ‘Castro Marin’.

You began to strum and then you kissed me,

In the groove, you got a rhythm going.

In no time your fingers found a melody;

You called it ‘The Cloud of Unknowing’.

The fall of your hair, the tap of your foot—

Why do you move me so?

I fall in love all over again—

And fix you an Irish Cream and Curaçao.

And then of a sudden you stop and say:

I’ve got it!

You pick up notepad and pencil,

You scribble and calculate.

And when the paper is published,

I read in the ‘Thank you’ line:

A special thanks to Sprague

For the Spanish guitar on my birthday.

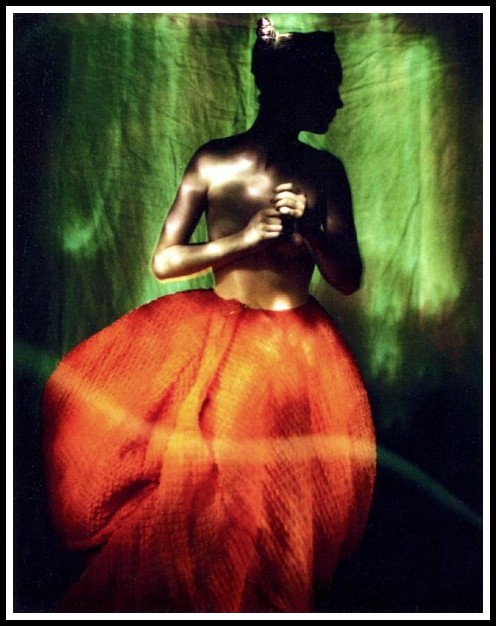

Paolo Roversi, Guinevere, Paris 1996

4. PLOUGHING THE FIRST FURROW

In Zürich, in your bedroom overlooking the lake,

I lay on your bed, barefoot and stripped to the waist,

And watched you pack away your winter clothes,

Unpack your summer things.

Mothballs for woollens, boots in boxes,

Coats in garment bags. And then the emergence

Of crepe-de-Chine tops and cropped trousers,

Bold-print dresses, sandals and skirts.

As the sun streamed through the window,

I watched you take off your jeans and T-shirt

And put on a tank top and billowing skirt.

I tossed you a straw hat from a box: You put it on.

And then I rose from the bed and approached you.

I took off your straw hat and in a zigzag of sunlight

Laid you down on the floorboards. In Sanskrit

I uttered a blessing, then crept up under your skirt.

Between your legs I performed the ritual of Spring,

It’s called ‘ploughing the first furrow’.

You’d worn the sacred headdress, I’d pronounced

The blessing. It was a wonderful summer.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

5. HUFF, HUFF

Drooling dogs roam empty streets,

Seeking insects under ashes.

Huff, huff, they whiff the dust:

Tongueless mouths struggle to feed.

Across fractured logs haggard dogs

Stagger, their yellowy eyes oozing.

Huff, huff, they whiff the dust:

Toothless mouths struggle to feed.

Skeletal dogs on a burning plain

Drag their bones and dig;

Deeper and deeper they dig,

Until their graves are dug.

Paolo Roversi, Audrey, Paris 1996

6. ASTONISHMENT

Trances, phantoms, hallucinations,

Death, sleep, dreams:

Between chaos and cosmos,

The natural and the revealed,

I seek neither the choice that justifies

Nor the road to salvation.

What then?

Nothing. I embrace all:

The land of spirits, the realm of shades,

The ethereal fire, the earthly flame.

Where do I stand?

I stand in this moment,

I lie on this bed;

Marietta is with me,

In nakedness and grace:

That is enough for me.

Enough?

Yes, enough. I am content

To survey the world

With her legs as my compass,

Her pussy the hinge.

I am content to find in her breasts

The vast abstract permanences

That underlie the flux of things.

Content?

Yes, I am content

To make of astonishment

A language for deciphering the world:

That is enough for me.

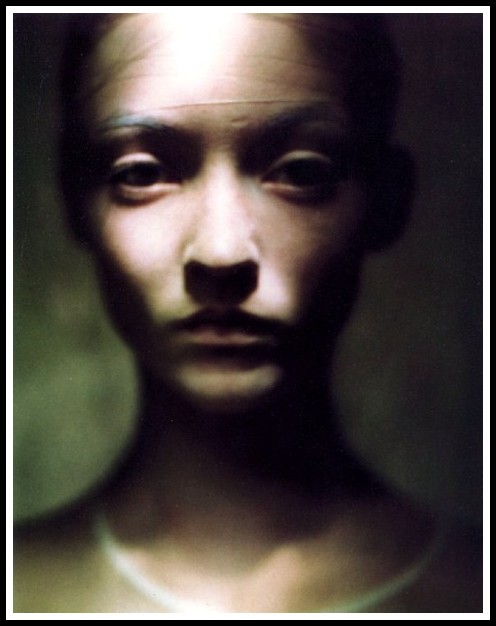

Paolo Roversi, Sasha, Paris 1985

7. CONSUME ME IN YOUR FLAME

Who will restore me to my name?

I am fossil, I am sediment,

I am compacted of altered remains;

I am hard, I am stratified,

I am metamorphosed but still the same:

Mara, consume me in your flame!

Paolo Roversi, Sasha, Paris 1985

8. HUMILITY

We both know that having a roof

Is no assurance of shelter;

We’re both convinced the biggest fool

Is the one who believes he can’t be foolish.

Not for us the familiar mirror,

But the uncanny looking glass;

Not for us the fixity of closure,

But the flux of openness.

Too demanding not to desire the truth,

Too modest to reduce the world to it:

We both know that humility—

Not intelligence—

Is the opposite of stupidity.

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

9. INGRID

Sometimes, Ingrid, your smile

Is as fragile as the moon in a morning sky;

Sometimes your regard

Is as hard as tempered steel.

Sometimes you’re the hunter,

The hawk at one with the wind,

Suspending the world on a wingbeat

In pursuit of the hare.

Sometimes you’re the hunted,

The hare—nostrils flared, heart racing—

Standing petrified

In the shadow of the hawk’s wing.

But hunter or hunted, hawk or hare,

When you gaze into my eyes

All the world folds into a corner of your smile,

And I recognize my incestuous sister.

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

10. TWO PHOTOS

You refuse the eye the possibility

Of appropriating any one part of your body:

Tying desire up in knots, you intensify it

In a harmony of forces and counter-forces

You affirm your subjectivity:

Acceding to submission, you assert your sovereignty

Paolo Roversi, Kirsten, Paris 1987

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

The question of ‘poetry, fiction and the private self’ is inescapable when it comes to Mara, Marietta. Not everything in the novel is fact, but everything is true. John Fowles asserts that ‘it is rather difficult to put one’s private self into a novel’. Difficult, yes, but when, in the heat of the struggle to express the truth of one’s experience one forges devices that enable one to do so artistically, then the attempt is well worth while. Such was the challenge I undertook in writing my book. I leave you, dear reader, to decide how well I’ve met it.

Poetry, Fiction and the Private Self

THE POET AND THE NOVELIST

John Fowles

Abbreviated from ‘Foreword to the Poems’ (1973) in John Fowles, Worm Holes: Essays and Occasional Writings, ed. Jan Relf (London: Vintage, 1999) pp. 30-31

I should like to say briefly where poetry sits in my writing life. The so-called crisis of the modern novel has to do with its self-consciousness. The fault was always inherent in the form, since it is fundamentally a kind of game, an artifice that allows the writer to play hide-and-seek with the reader. In strict terms a novel is a hypothesis more or less ingeniously and persuasively presented—that is, first cousin to a lie. This uneasy consciousness of lying is why in the great majority of novels the novelist apes reality so assiduously; and it is why giving the game away—making the lie, the fictitiousness of the process, explicit in the text—has become such a feature of the contemporary novel. Committed to invention, to people who never existed, to events that never happened, the novelist wants either to sound ‘true’ or to come clean.

Javier Vallhonrat, Paris, 1987

Poetry proceeds by a reverse path; its superficial form may be highly artificial and invraisemblable, but its content is normally a good deal more revealing of the writer than is that of fiction. The poem is saying what you are and feel, the novel is saying what invented characters might be and might feel. Only very naive readers can suppose that a novelist’s invented personages and their opinions are reliable guides to his real self. Of course some poets wear masks (though much more for rhetorical than for seriously deceitful reasons), and of course there is an autobiographical element in all novels. Nonetheless, I think there is a vital distinction. It is rather difficult to put one’s private self into a novel; it is rather difficult to keep it out of a poem. A novelist is like an actor or actress onstage, and the private self has to be subjugated to the public master of a novel’s ceremonies. The primary audience is other people. A poet’s is his or her own self.

Enrique Badulescu, No Direction, 1989

This may, I think, partly explain why some writers are poets and others novelists, and why excellence in both forms is such a rare thing. I suspect that most novelists are trying to camouflage a sense of personal inadequacy in the face of real life—a sentiment that is compounded in the act of creating fiction, the fabrication of literary lies, ingenious fantasies, to hide a fundamental psychological or sociological fault of personality. Some novelists—Hemingway is the classic instance—create a real-life as well as a literary persona in answer to this predicament. Most genuine poets have a much happier, or less queasy, relationship with their private self. At least they do not live, like most novelists, in permanent flight from the mirror.

Satoshi Saikusa, Paris 1988

At any rate I have always found the writing of poetry, which I began before I attempted prose, an enormous relief from the constant play-acting of fiction. I never pick up a book of poems without thinking that it will have one advantage over most novels: I shall know the writer better at the end of it. I do not have to hope this is true of my poems. I know it is true—and know also how slender a justification mere personal truth is for writing. Martial’s line—Go on, run away, but you’d be far safer if you stayed at home—reflects my feelings on the matter.

Satoshi Saikusa, Paris 1990

RELATED POSTS IN THE WORLD OF MARA MARIETTA