Sprague’s Poems III

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

All poems © Richard Jonathan 2017. All rights reserved.

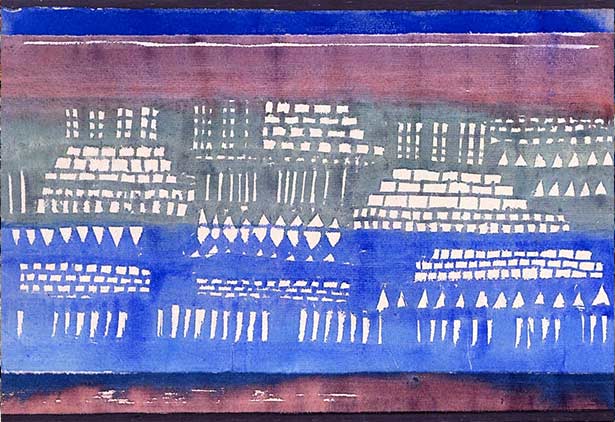

Paul Klee, Foundations of K, 1928

Mine to Learn

Teach me to walk the high-wire,

Till I vanquish my need to fall;

Teach me to turn my back,

On the irreversible.

May I always meet you

In the place you cannot master;

May I always complete you

Without making you whole.

I feed on your hunger,

You feed on my greed:

You are inexhaustible

And everything is mine to learn.

Pure Wagner

The bold demeanour of your breasts,

The rose-petal lips of your pussy;

The arch of your instep,

The refinement of your fingers,

The dimples in the small of your back:

They are pavane and bolero,

Madrigal and canticle,

Sonata, concerto and symphony to me.

Yes, your breasts are Ravel, your ass Purcell,

And your pussy, pure Wagner!

Open, to Grace

Stand to face me beloved

And open out the grace of your eyes:

It comes to me now, this fragment of Sappho;

It comes to me from the depths of my soul.

Sappho, I hear your voice in the hills of Mitylene,

I hear your lyre in the mixolydian mode:

With unabashed frankness you reveal yourself,

With undeceived insight you lay love bare.

I would like to pay you homage, however humbly;

I would like to pass on what you have given me:

The conviction that love needs no premeditation,

That in the being of another one’s self expands.

And so I tune my lyre to your intonations,

From my lyric I expunge ornament and explanation:

It is enough that I open myself to grace.

Must it end?

If tragedy is ruled out by free love,

The rites of separation withstand;

If undoing our ties undoes me,

What of the telling of a story that ends?

What remains?

Your blue sweater, your black cap,

Your long hair loose;

Your smile, your walk,

The touch of your hand.

Must it end, my love?

I still have so much to learn.

You are the sea,

Refusing no river yet never filled,

Washing every shore yet never emptied:

You are inexhaustible

And everything is mine to learn

Must it end?

A Lesson in Ethics

You could yearn for your virginity

When we make love;

You could hold back and be evasive

When we talk.

You do not.

Instead, you look me in the eye,

You beat your wings and burn me.

You could play hide-and-seek,

You could leave me in the lurch.

You could be present

Without being present to me.

You could say,

Wrapping cruelty in generosity,

‘Let us remain friends’.

You do not.

Instead, you fold a lesson in ethics

Into your lesson in love,

You give me the lushness of your presence

In this barren landscape.

Is that why,

In this phantasmagoric geology,

In this distillation of the elements

To their essence,

I feel such humility?

Do Not Show Me Stars

Do not show me stars:

I don’t want to conceive of distances.

Do not hold me too closely:

I may never let you go.

The lapping of the water,

The sailors’ lullaby;

The lapping of the water—

Boys don’t cry.

You are all the moments

We have lived together;

You are all the lightness

I’m about to lose.

No Subtleties in the Sunset

Who do you think you are?

Do you really believe there can be a transition?

Are you so naïve as to assume her ghost will comfort you?

I tell you, there’ll be no subtleties in the sunset:

Upon a wasteland swept by an icy wind

Darkness will descend, unvarying.

Nothing will change that.

Nothing and no-one.

Face it.

Didn’t you say you want to live out this loss in reality?

My Viking

Oh conquer me, my beloved,

Claim me as your own;

Take me as your husband,

I will build you a home.

We’ll live on fish and berries,

We’ll live on knowledge and love;

We’ll have a clutch of kids,

And books undreamed of.

Visions form Blindness

Never in a million years

Will I forget your resplendence

Forever and a day

I will admire your intransigence

Never in a million years

Will I forget your loving-kindness

Forever and a day

I will draw visions from blindness