Five Theses on Love & Sex in Geoffrey Hill’s Poetic Sequence

GEOFFREY HILL’S ‘THE SONGBOOK OF SEBASTIAN ARRURRUZ’ – ANALYSIS

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

In this post I present five theses on love and sex in Geoffrey Hill’s ‘The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz’. The style of the essay is inspired by Walter Benjamin’s ‘Theses on the Philosophy of History’ and Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia. If I am but a speck of dust in the constellation of that duo, I nevertheless aspire to imbue my work with the spirit that scintillates in theirs. But, before the theses, the poetic sequence: here are the eleven poems that make up Geoffrey Hill’s ‘The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz’.1

1 – From Geoffrey Hill, Broken Hierarchies: Poems 1952–2012, Kenneth Haynes, editor (London: Oxford University Press, 2013) pp. 69-79.

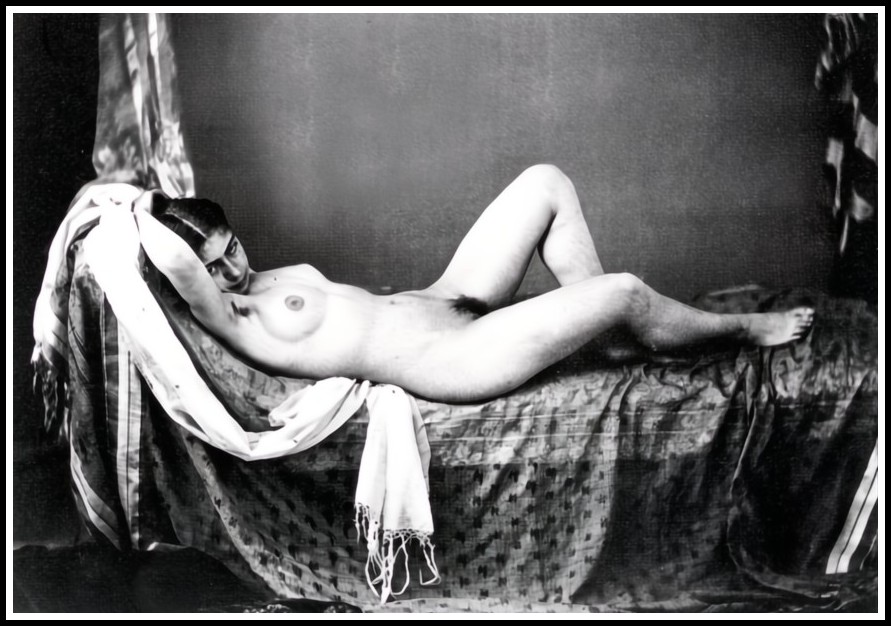

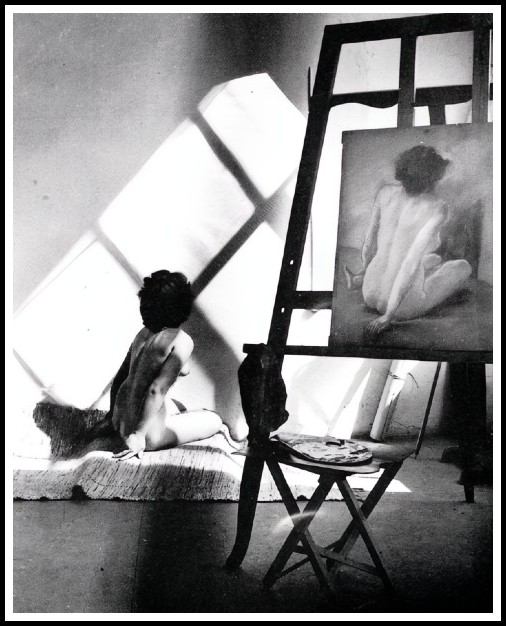

E. Durieu, Modèle de dos, 1854

The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz

Sebastian Arrurruz: 1868-1922

I

Ten years without you. For so it happens.

Days make their steady progress, a routine

That is merciful and attracts nobody.

Already, like a disciplined scholar,

I piece fragments together, past conjecture

Establishing true sequences of pain;

For so it is proper to find value

In a bleak skill, as in the thing restored:

The long-lost words of choice and valediction.

E. Durieu, Étude pour Delacroix, 1854

COPLAS

i

‘One cannot lose what one has not possessed.’

So much for that abrasive gem.

I can lose what I want. I want you.

ii

Oh my dear one, I shall grieve for you

For the rest of my life with slightly

Varying cadence, oh my dear one.

iii

Half-mocking the half-truth, I note

‘The wild brevity of sensual love’.

I am shaken, even by that.

iv

It is to him I write, it is to her

I speak in contained silence. Will they be touched

By the unfamiliar passion between them?

L.-C. d’Olivier, Étude de nu, 1855

3

What other men do with other women

Is for me neither orgy nor sacrament

Nor a language of foreign candour

But is mere occasion or chance distance

Out of which you might move and speak my name

As I speak yours, bargaining with sleep’s

Miscellaneous gods for as much

As I can have: an alien landscape,

The dream where you are always to be found.

L.-C. d’Olivier, Étude de nu, 1855

4

A workable fancy. Old petulant

Sorrow comes back to us, metamorphosed

And semi-precious. Fortuitous amber.

As though this recompensed our deprivation.

See how each fragment kindles as we turn it,

At the end, into the light of appraisal.

Gilmer, Nu féminin allongé, 1870

5

Love, oh my love, it will come

Sure enough. A storm

Broods over the dry earth all day.

At night the shutters throb in its downpour.

The metaphor holds; is a snug house.

You are outside, lost somewhere. I find myself

Devouring verses of stranger passion

And exile. The exact words

Are fed into my blank hunger for you.

Gilmer, Nu féminin allongé, 1870

POSTURES

I imagine, as I imagine us

Each time more stylized more lovingly

Detailed, that I am not myself

But someone I might have been: sexless,

Indulgent about art, relishing

Let us say the well-schooled

Postures of St Anthony or St Jerome,

Those peaceful hermaphrodite dreams

Through which the excess of memory

Pursues its own abstinence.

E. Durieu, Étude de modèle, 1854

FROM THE LATIN

There would have been things to say, quietness

That could feed on our lust, refreshed

Trivia, the occurrences of the day;

And at night my tongue in your furrow.

Without you I am mocked by courtesies

And chat, where satisfied women push

Dutifully toward some unneeded guest

Desirable features of conversation.

L. Bonnard, Étude de nu, 1881

A LETTER FROM ARMENIA

So, remotely, in your part of the world:

the ripe glandular blooms, and cypresses

shivering with heat (which we have borne

also, in our proper ways) I turn my mind

towards delicate pillage, the provenance

of shards glazed and unglazed, the three

kinds of surviving grain. I hesitate amid

circumstantial disasters. I gaze at the

authentic dead.

L. Bonnard, Étude de nu, 1881

A SONG FROM ARMENIA

Roughly-silvered leaves that are the snow

On Ararat seen through those leaves.

The sun lays down a foliage of shade.

A drinking-fountain pulses its head

Two or three inches from the troughed stone.

An old woman sucks there, gripping the rim.

Why do I have to relive, even now,

Your mouth, and your hand running over me

Deft as a lizard, like a sinew of water?

L. Bonnard, Étude de nu, 1881

TO HIS WIFE

You ventured occasionally—

As though this were another’s house—

Not intimate but an acquaintance

Flaunting her modest claim; like one

Idly commiserated by new-mated

Lovers rampant in proper delight

When all their guests have gone.

L. Bonnard, Étude de nu, 1881

II

Scarcely speaking: it becomes as a

Coolness between neighbours. Often

There is this orgy of sleep. I wake

To caress propriety with odd words

And enjoy abstinence in a vocation

Of now-almost-meaningless despair.

L. Bonnard, Étude de nu, 1881

THESIS I – NO COUPLE, NO CONSPIRACY, NO CRIME

‘One cannot lose what one has not possessed.’ Was it she who planted that arrow in his breast? Was she, perhaps, provoking him to finally possess her? Was she daring him ‘to restore to the sexual drive its diabolical capacity, it’s potential for disruption’?1 In short, was her remark meant to incite him to ravish her? ‘A couple is a conspiracy in search of a crime. Sex is often the closest they can get.’2 He writes: ‘The wild brevity of sensual love’. / I am shaken, even by that. Was he not up to it, then? Was ‘my tongue in your furrow’ all he could manage? There was no couple, no conspiracy, no crime: she waited in vain for a ravishing lover to wrench her sexuality from her craving vacancy. ‘A cunt’, writes Leonard Cohen in The Energy of Slaves, ‘must needs be houseproud’.3 She, unawakened, was not houseproud. He writes: You ventured occasionally / As though this were another’s house / Not intimate but an acquaintance / Flaunting her modest claim. What had she, dormant like Sleeping Beauty, to be proud of? Indeed, New-mated / Lovers rampant in proper delight, could only pity her. Is it any wonder, then, that she flung at him that abrasive gem?

1 – Jacqueline Schaeffer, ‘The Riddle of the Repudiation of Femininity: The Scandal of the Feminine Dimension’, in Leticia Glocer Fiorini & Graciela Abelin-Sas Rose, editors, On Freud’s ‘Femininity’ (London: Karnac Books, 2010) pp. 130

2 – Aphorism 21 in Adam Phillips, Monogamy (London: Faber & Faber, 1996).

3 –‘This is the only poem’, in Leonard Cohen, The Energy of Slaves (London: Jonathan Cape, 1972) p. 12

G. Le Gray, Étude de nu, 1855

THESIS II – THE FIGURES OF LANGUAGE ARE NOT FETISHIZED: SELFHOOD & SUBJECTIVITY

It is a truism of literary practice that, in endeavouring to write about love and sex without embarrassing oneself, detour gives access, the oblique makes presentable, and distance saves face. Only writers who assume their individuality and forge a style that’s true to it, however, get beyond the ‘cleverness’ and game-playing, the conventional anti-conventions, and the coyness that characterize the output of the in-crowd: the postmodernists. For these ‘clever’ writers, ‘a moment of true feeling’ would bring down their house of cards, so they dare not take the risk. Geoffrey Hill, in ‘The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz’, adopts an overarching distancing device—a persona who speaks the poems in a reflexive, ironic self-questioning—a device that, far from evacuating feeling, gives it form and resonance. His postmodernism is humanist. He uses metafiction to reinforce, rather than undermine, the poet’s subjectivity. In other words, he does not fetishize figures of language, as the in-crowd does, but uses them to serve the workings of his hero’s mind as he uses them. The poetic sequence gives us a vision of the poet ‘in tension with, rather than inertly constituted by, the language that so conditions him’. This formulation is that of Peter Sacks, and I offer his elaboration of it below.

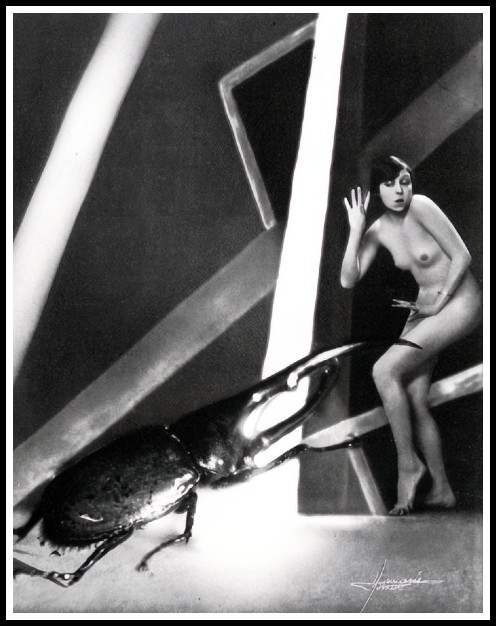

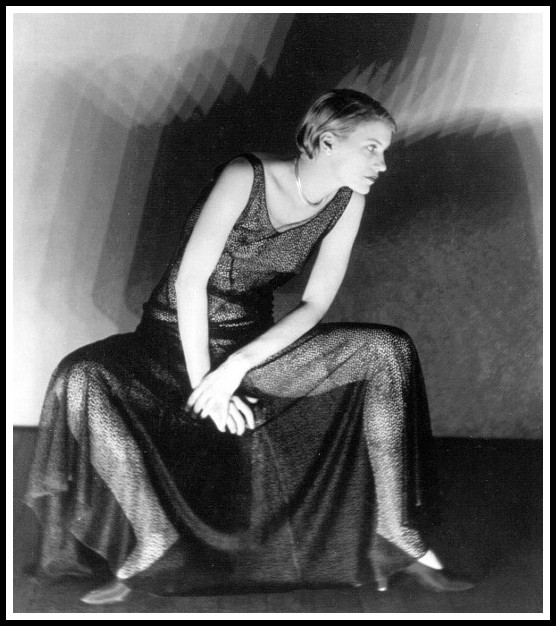

Manassé, 1930

In his book, The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spenser to Yeats,1 Peter Sacks writes: Several current critical approaches have not only challenged the compensatory nature of literature by exposing the fabrications of its rhetoric; they have also tended to evaporate the pathos of disjunction and loss by regarding these not humanistically, in relation to language, but scientifically, as inherent features of the structure of signification itself. By beginning with the assumption that an essential lack is already inscribed within language, and hence within its user, this view risks abandoning a true sense of the experience of loss. One should beware of how easily the problem of subjectivity may be elided if its entire assimilation to the status of language is taken for granted. So thoroughly have we been told to regard the self as scarcely different from yet another textual structure that we have retained little sense either of what that ‘scarcely different’ might mean or of the pain and resistance that go into the making of that structure. In ‘The Songbook of Sebastian Arrurruz’, Geoffrey Hill shows us ‘the connections between language and the pathos of human consciousness’, to borrow another phrase from Peter Sacks, and it is precisely his dialectical depiction of this pathos that makes his postmodernism humanist. Unlike the in-crowd, he does not regard the self as ‘yet another textual structure’. For him, ‘selfhood is more vital, recalcitrant, abiding, than self-expression’.2 And, I might add, ‘more vital, recalcitrant, abiding’ than what drives the output of the in-crowd. Selfhood and subjectivity: without these, love and sex in literature are devoid of tension, hence without interest.

1 – Peter M. Sacks, The English Elegy: Studies in the Genre from Spenser to Yeats (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1985) pp. xi-xii

2 – Geoffrey Hill quoted in Andrew Michael Roberts, ‘Romantic irony and the postmodern sublime: Geoffrey Hill and “Sabastian Arrurruz’”. In Romanticism and Postmodernism, ed. Edward Larrissy (Cambridge University Press, 2010 [1999]) p. 146

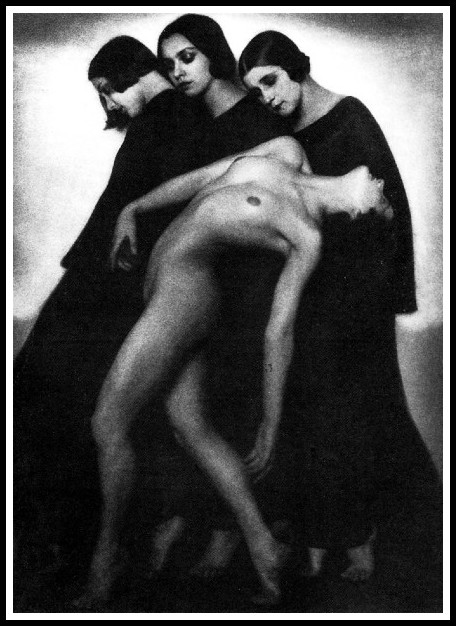

Frantisek Dritkol, 1930

THESIS III – RECASTING THE ORIGINAL: A FRAGILE CONSOLATION

He writes: It is to him I write, it is to her / I speak in contained silence. Will they be touched / By the unfamiliar passion between them? ‘A sexual relationship is like learning a script neither of you have read. But you only notice this when one of you forgets your lines. And then, in the panic, you desperately try and remember something that you haven’t really forgotten. You hope the other person will prompt you. You start to hear voices off. You bring in another character.’1 He’s good at that, Sebastian, bringing in another character. Who is ‘him? Who is ‘her’? My guess is that they are recast versions of the original couple. The poet is a god: Breathe in and he obliterates the world; breathe out and he brings it back anew. All while sitting at his desk, blackening a page. He writes: I imagine, as I imagine us / Each time more stylized more lovingly / Detailed, that I am not myself / But someone I might have been. Sculpted in time, forms emerge from the blackened page, no longer tentative but well-defined. Once trances, phantoms, hallucinations—now characters as close to him as his jugular vein. Why this obsession to recast the past? ‘There is no such thing as sexual competition, there is only the continual coming to terms with the fact that one can never be someone else to one’s partner, that we are so quickly typecast in our relationships. Our rivals are merely other people. They are helpless, like us, because they only have one real advantage over us, and it is always decisive. They will never be us.’2 And so, as a consolation for loss, the poet has the leopard change his spots. Fat lot of good it will do him if he ever meets up with his ex again!

1 – Aphorism 77 in Adam Phillips, Monogamy (London: Faber & Faber, 1996).

2 – Aphorism 54 in Adam Phillips, Monogamy (London: Faber & Faber, 1996).

Yva, 1940

THESIS IV – MEMORY AND DESIRE IN TENSION: A RESTLESS NOSTALGIA

He writes: Ten years without you. For so it happens. / Days make their steady progress, a routine / That is merciful and attracts nobody. Ten years is a long time. The mercy of routine. Comes a day her face won’t leave his mind: Oh my dear one, I shall grieve for you / For the rest of my life with slightly / Varying cadence, oh my dear one. Self-mocking cynicism. An old trick. She remains in his mind’s eye: he blindly forges ahead: What other men do with other women / Is for me neither orgy nor sacrament / Nor a language of foreign candour / But is mere occasion or chance distance / Out of which you might move and speak my name / As I speak yours, bargaining with sleep’s / Miscellaneous gods for as much / As I can have: an alien landscape, / The dream where you are always to be found. Is to indulge the dream to renounce reality? Is memory enough to satisfy desire? Speak my name / As I speak yours: To name is intimacy itself. Can the flesh be so easily foreclosed? A workable fancy. Old petulant / Sorrow comes back to us, metamorphosed / And semi-precious. Fortuitous amber. / As though this recompensed our deprivation. / See how each fragment kindles as we turn it, / At the end, into the light of appraisal. The autopsy of a marriage. Doctor Tulp’s Anatomy Lesson. No, I am being unfair. He does say, ‘As though this recompensed our deprivation’. But didn’t he declare, a moment ago, ‘What other men do with other women / Is for me neither orgy nor sacrament’? ‘In marriage we are never quite sure who the joke is on.’1

1 – Aphorism 47 in Adam Phillips, Monogamy (London: Faber & Faber, 1996).

Rudolf Koppitz, 1927

He writes: Scarcely speaking: it becomes as a / Coolness between neighbours. Often / There is this orgy of sleep. I wake / To caress propriety with odd words / And enjoy abstinence in a vocation / Of now-almost-meaningless despair. ‘The only philosophy which can be responsibly practised in the face of despair is the attempt to contemplate all things as they would present themselves from the standpoint of redemption.’1 Where does the horizon lie? Where is the standpoint of redemption? Can it be constituted by an exquisite arrangement of words, a sublime concatenation of syllables? One dares to believe it might: Love, oh my love, it will come / Sure enough. A storm / Broods over the dry earth all day. / At night the shutters throb in its downpour. / The metaphor holds; is a snug house. But no, the poem will not dissolve on her tongue like a communion wafer and spiritualize her body: she remains carnal, ‘outside, lost somewhere’. Again, he blindly forges ahead: I find myself / Devouring verses of stranger passion / And exile. What is he reading? The Beauty of the Medusa? The Metamorphoses of Satan? The Shadow of the Divine Marquis? La Belle Dame Sans Merci? No, something more austere, no doubt; something other than Romantic Agony. The exact words / Are fed into my blank hunger for you. ‘Blank hunger’, ‘devour’—he wants, it seems, to introject her, that she may abide forever within him. Does he not know that without alterity he is doomed? His nostalgia is a rag-and-bone man rummaging in his body of memory and only ever finding the memory of her body: as long as that holds, redemption will remain elusive. And poetry will flourish.

1 – Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life, trans. E. F. N. Jephcott. (London: Verso, 2005) p. 247

Manassé, 1935

THESIS V – THE IRRESISTIBLE ENACTMENT OF DESIRE

Practiced a certain way, artistic creation and sexual intercourse are both transgressive acts. As such, they often feed off each other. Thus, he writes: There would have been things to say, quietness / That could feed on our lust, refreshed / Trivia, the occurrences of the day; / And at night my tongue in your furrow. The poem is titled, ‘From the Latin’. The language that conceals reveals: cunnilingus. Layered meanings, mises-en-abîme: a typical Hill touch in the ‘Songbook’. A drinking-fountain pulses its head / Two or three inches from the troughed stone. / An old woman sucks there, gripping the rim. / Why do I have to relive, even now, / Your mouth, and your hand running over me / Deft as a lizard, like a sinew of water? The sight of the pulsing fountain, the woman gripping and sucking: in the magic lantern of his mind he sees his (ex-)lover’s mouth (fellatio is not far away), and her hand caressing him in magnificent metaphors: making poetry and making love have here become one. Gone are the ‘hermaphrodite dreams / Through which the excess of memory / Pursues its own abstinence’: here, lust rides roughshod over reserve. Tongue, furrow, mouth, hand: the desiring body enacts the rites of love.

Man Ray, Lee Miller, 1929

FIVE POEMS FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’

Richard Jonathan

ONE

Marietta

Making love with Izolda

I didn’t fantasize about you,

But now that she’s gone

I do: The bold demeanour

Of your breasts,

The rose-petal lips of your pussy;

The arch of your instep,

The refinement of your fingers,

The dimples in the small of your back:

They are pavane and bolero,

Madrigal and canticle,

Sonata, concerto and symphony to me.

Yes, your breasts are Ravel, your ass Purcell,

And your pussy, pure Wagner!

Photo: Catherine Gratwicke

TWO

Precious one, today is your birthday

And I am all undone. Why can’t I accept

That without you my dwelling place

Is the rain, the stars and the river,

And the wide open spaces the wind

Blows through?

You gave me all your love,

You filled my spine with memories: True.

But ever since you left me

I’ve been living unsheltered, defenceless

Against the wind that blows

Your absence through my bones.

How long can this missing you go on?

Because I know I will never take shelter,

I know it will never end. Because I know

Your memory keeps me alive, I know

I am condemned. To what?

To missing you till my bones ache,

To being a mourner at my own wake.

Photo: Catherine Gratwicke

THREE

Transparent as your absence

Juniper in gin

I am steeped in sadness

Emptiness within

Nothing is the sum

Of all things without you

Hollow and numb

I can’t forget you

Photo: Catherine Gratwicke

FOUR

The coin of Tyche, the stretched string;

Pattern, order and chaos:

Between contingency and necessity

Between reason and the absurd

I find myself adrift.

The gathering of thought, the mnemonics of pain;

Memory, forgetting and healing:

Between oblivion and presence

Between obsession and lucidity

I find myself adrift.

The sovereignty of the self, the question of self-concealment;

Love, knowledge and delusion:

Between action and introspection

Between melancholy and exuberance

It find myself adrift.

Marietta, what I am to do?

Won’t you help me,

Help me to live without you?

Photo: Catherine Gratwicke

FIVE

If tragedy is ruled out by free love,

The rites of separation withstand;

If undoing our ties undoes me,

What of the telling of a story that ends?

What remains?

Your blue sweater, your black cap,

Your long hair loose;

Your smile, your walk,

The touch of your hand.

Must it end, my love?

I still have so much to learn.

You are the sea,

Refusing no river yet never filled,

Washing every shore yet never emptied:

You are inexhaustible

And everything is mine to learn

Must it end?

Photo: Catherine Gratwicke

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments