Anaïs Nin

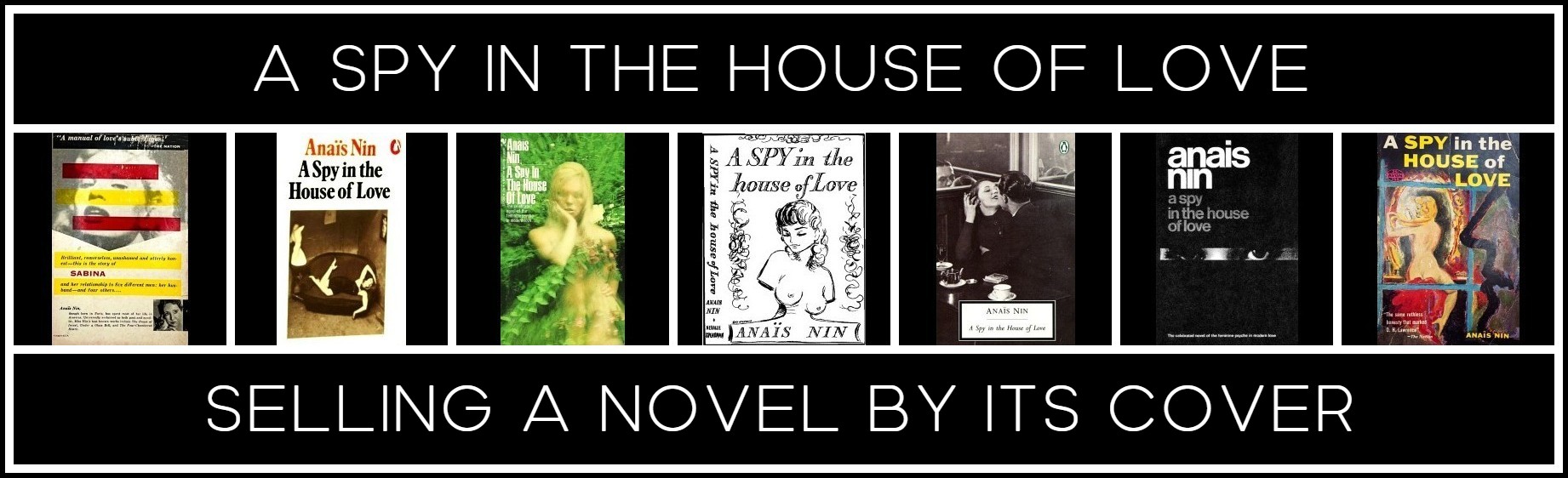

A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: SELLING A NOVEL BY ITS COVER

Benjamin Franklin V

From Benjamin Franklin V, ‘Selling A Spy in the House of Love’ in Suzanne Nalbantian, editor, Anaïs Niin: Literary Perspectives (New York: Saint Martin’s Press, 1997 (pp. 254-277). Intertitles added, and text slightly abbreviated, by Richard Jonathan.

I. INTRODUCTION

Anaïs Nin began her career as a serious author in France where, in the 1930s, her first three books appeared. Because she could find no publisher interested in her fiction after moving to the United States, in the early 1940s she established the Gemor Press in New York and published her own work. A few years later, she secured a contract with E.P. Dutton for two of her novels and a collection of short fiction: Ladders to Fire (1946), Children of the Albatross (1947) and Under a Glass Bell and Other Stories (1948). This contract was arranged by Gore Vidal, then a Dutton editor and a friend of Nin. Not one of these books required a second printing, and Dutton elected to publish nothing more of hers. Duell, Sloan and Pearce published Nin’s next novel, The Four-Chambered Heart, in 1950; British Book Centre published A Spy in the House of Love in 1954. Not dramatically different in content from Nin’s first three novels, A Spy in the House of Love has achieved a popularity unlike any of her other long fictions, which also include Seduction of the Minotaur (1961) and Collages (1964). I base this statement on the fact that of her novels, Spy has had the greatest number of American and English publishers and has gone through the most editions and printings by far. I would like to think it has received such attention because of its intrinsic quality, but surely this is not the case. Rather, it is the most often published and therefore the best known of Nin’s novels because of its title, which suggests an overt, explicit sexuality not found in the text. In this essay I examine the design, including pictures and photographs, of the dust-jackets and paperback covers of American and English editions of Spy in an effort to understand how various publishers have presented it to prospective book purchasers.

The novel concerns Sabina, a recurrent figure in Nin’s fiction, who attempts to overcome the psychological problems which began in childhood with her parents’ betrayals of her. This 30-year-old woman reflects on the effect of their behaviour and concludes that in order to compensate for their coldness and indifference, she has sought the marvellous at the expense of facts, of truth. Her life has therefore been a lie. Married to Alan, this woman of emotional and psychological parts tries to find wholeness and happiness (and, psychologically, to punish her philandering father) by engaging in sexual affairs with Philip, Mambo and John, and by entering into an odd relationship with Donald as his nourisher (providing the support her mother denied her). Not one of these men truly satisfies her. Because Alan cannot comprehend that she has changed over time, he loves the Sabina he wed ten years ago, not the woman she now is. In loving several men physically and bolstering Donald, she loves none of them emotionally. Although her friends Jay and Djuna try to help her understand and become comfortable with herself, in the end she remains an incomplete woman, ‘the international spy in the house of love’, a woman with no real emotional connections, a person apart from herself.

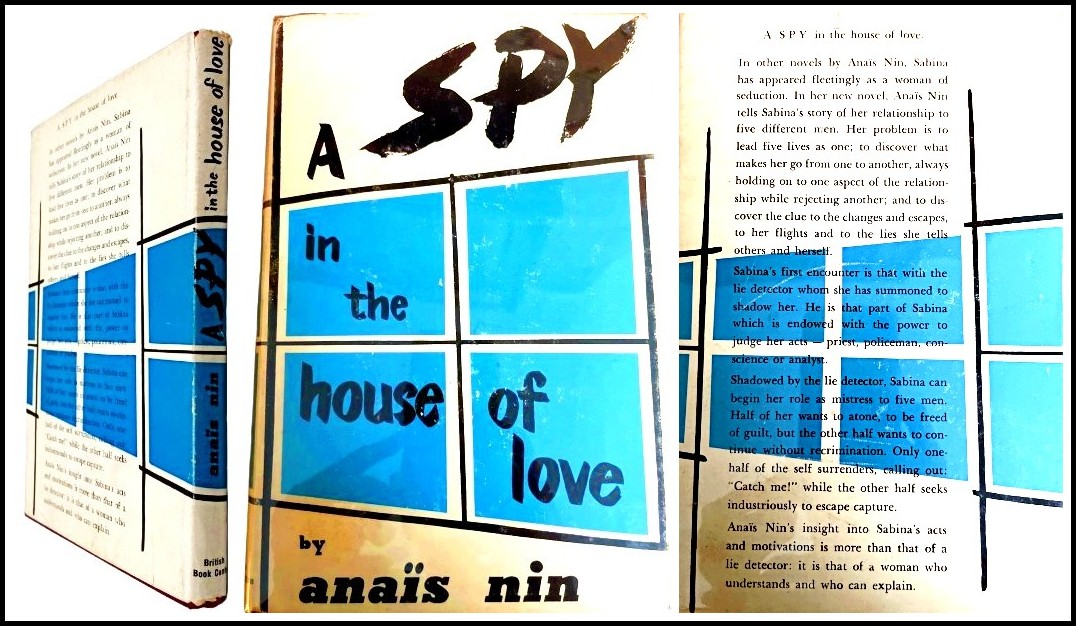

II. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: BRITISH BOOK CENTRE

Because Nin was known primarily as an avant-garde writer and not as a commercially established author, British Book Centre could not count on her name to sell many copies of Spy when it published this unrealistic novel in 1954. It could hope for positive reviews, possibly by prestigious writers in important publications, but it could also try to attract buyers by fashioning an engaging dust-jacket. So how should the jacket designer proceed? He could create a jacket to exploit the sexual implications of the title, but he did not. Instead, he relied primarily on abstract design and bold lettering to encourage potential readers to buy the book. Two aspects of the front dust-jacket immediately attract attention. First, the word ‘spy’ is at least twice the size of all other words, and it appears to have been written by someone using black finger paint. Who? And why? Size and style thus create an air of mystery by emphasizing spying and intrigue. And while Spy is not a cloak-and-dagger thriller, it concerns the intrigue of Sabina spying on herself, trying to understand herself and make herself whole. So in a sense, this aspect of the jacket design is faithful to the plot. Second, four blue, rectangular panels or windows consume much of the front cover, with others appearing on the spine, the back cover and the two flaps. When the dust-jacket is opened, these rectangles appear more to represent pictures in a gallery than windows in a house. They might suggest the men with whom Sabina is involved, or various aspects of Sabina herself.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1954 cover

British Book Centre chose to present Spy as a serious work and Nin as a serious author. The front flap contains blurbs by such well-known writers as Kay Boyle, Maxwell Geismar, Charles Rolo, Rebecca West and Edmund Wilson. The brief biographical information about Nin on the rear flap emphasizes her internationalism, notes that her Under a Glass Bell is ‘on the required reading list at Columbia University’, states that she has recorded some of her fiction, and concludes by mentioning her experimentation with ‘new forms and styles’. But the dust-jacket designer did not want to focus too sharply on Nin, for the reason already stated: her name would sell few copies of the book. This attitude on the part of the designer may be gleaned from the front cover, where ‘by anaïs nin’ appears at the bottom in the smallest of all the front cover letters. The author’s name is the last thing one notices. In emphasizing intrigue and abstraction, then, the British Book Centre jacket designer chose fidelity to the text over exploitation of the sexual possibilities of the title. This design had a long life. When Alan Swallow published the novel in 1966, he reproduced the British Book Centre design, and retained it until 1984.

Anaïs Nin

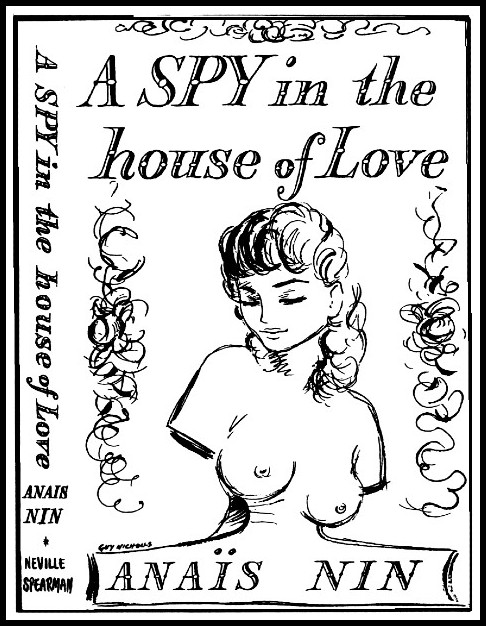

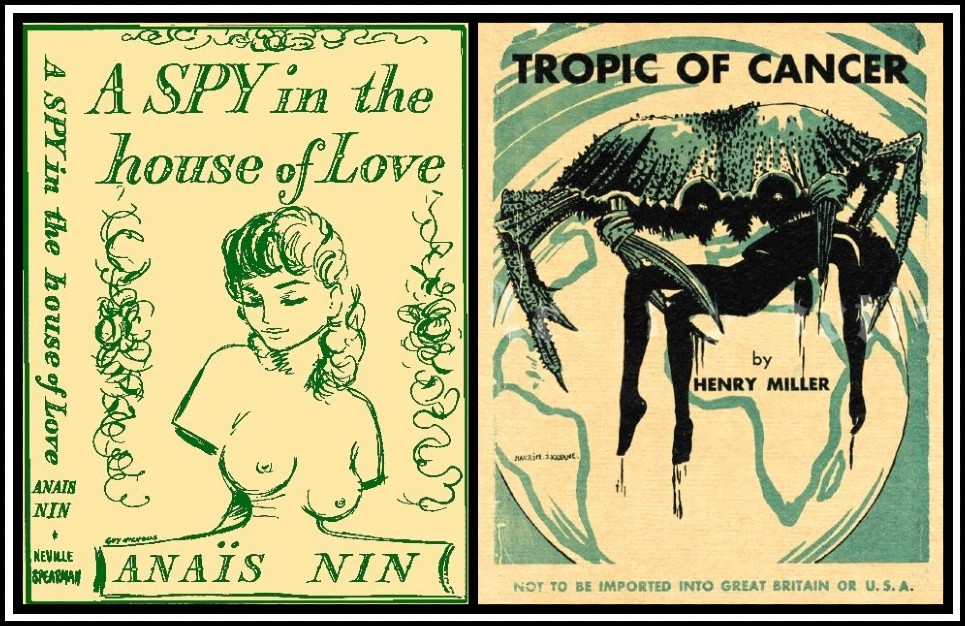

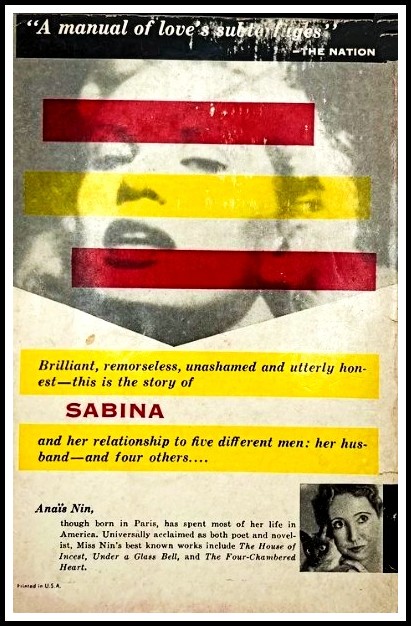

III. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: NEVILLE SPEARMAN

In 1955, Neville Spearman published Spy in London. Following the Editions Poetry London edition of Under a Glass Bell (1947), this is the second English edition of any of Nin’s books. Its dust-jacket design represents a dramatic change from the purity of the British Book Centre design. In capitalizing the first two words of the title, the designer chose to emphasize intrigue over eroticism. But the cover art, by Guy Nicholls, exploits the sexual possibilities of the title. The eye is immediately drawn to a bust of an armless woman reminiscent of Venus de Milo. This bust is not marble, however: in this drawing, the woman seems lifelike. Her ringletted hair falls to her shoulders, she has eyebrows and eyelashes, and her eyes are either closed or directed downward; her pendulous breasts have pronounced nipples. The bust rests on a base, which includes a woman’s name. One might expect this name to be that of the woman depicted in the bust. Instead of Venus de Milo, though, the name on the base is Anaïs Nin. In connecting Nin’s name with the bust, Nicholls means to imply both that the author, Nin, is a sexy woman and that the novel emphasizes the erotic.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1955 cover

Readers tempted to examine the book before buying it could have learned something about Nin, however. The back cover features a picture of her, seated, but appearing more demure than sexy. The brief biographical statement mentions her musician father and emphasizes her internationalism. It also mentions Henry Miller, even then notorious as the author of Tropic of Cancer. The back cover blurb notes that Neville Spearman has concurrently published Spy and Alfred Perlès’s My Friend Henry Miller, thus connecting Nin with Miller and implying that if Tropic of Cancer is a dirty book then so too is Spy. The front flap offers a brief summary of the novel and places Nin in the context of Virginia Woolf and Colette. It includes quotations from the British Book Centre edition: Rebecca West (‘Real and unmistakable genius’) and Edmund Wilson (‘She is a very great artist, who feels things we cannot feel’). In emphasizing spying, sex and Nin’s seriousness, Neville Spearman attempted to attract as many readers as possible. Either because of the cover art, because English readers found the novel to their liking, or because of an original limited Spearman print-run—or for all of these reasons—this edition required a second printing.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1955 cover colorized | Henry Miller, Tropic of Cancer, first edition (1934) cover

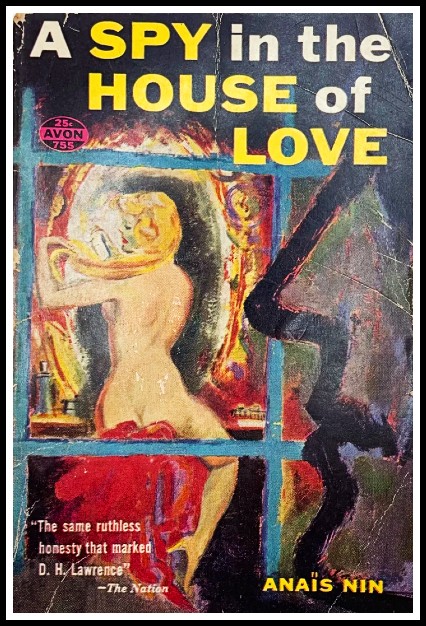

IV. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: AVON BOOKS

The most spectacular Spy cover art appeared in 1957 on the first mass-market paperback edition of any of Nin’s works. In choosing to publish Spy from among Nin’s fictions, Avon saw marketing possibilities with the title. Nin relates that she received a $1,250 advance from Avon and that Thomas Payne, its editor-in-chief, thought he could also sell Children of the Albatross by claiming ‘that children of the albatross is a name given to bastard children’. Clearly, Avon was in the business of selling books, even if it had to mislead potential buyers in order to do so. To sell Spy, Avon created a garish, sexy cover that would attract any browser of the paperback racks. In the title, the words ‘spy’, ‘house’ and ‘love’ stand out because they appear in yellow capital letters while the other words are in white lower case (the first word, ‘A’, is white and capitalized). Thus, the title emphasizes spying and sexuality, as does the cover art. In this night-time scene, a woman wearing only a pair of heels sits before a mirror spraying her long blonde hair. The cleft of her buttocks is clearly visible. Her appearance indicates that she is probably a harlot; the ornateness of the mirror and the red fabric on which she sits suggest she is in a brothel. And because she has taken no precaution to conceal herself from the view of passers-by, a man stands outside her window, ogling her.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1957 front cover

One may, of course, deconstruct the scene and read it as a statement of the woman’s confidence and power: she is not bashful, and the mirror permits her to spy on anyone who spies on her. She, not the man, controls the scene. She might also be advertising by offering a visual sampling of her wares. But no matter how one interprets the scene, prospective book buyers in 1957 would have expected the novel to provide the same voyeuristic delights as the man is experiencing while viewing the woman. To ensure that this message would not be missed, the cover also includes a quotation from The Nation: ‘The same ruthless honesty that marked D.H. Lawrence.’ Most people then considered Lawrence a writer of erotic books; therefore, Spy is an erotic book. All but lost on the cover is the author’s name, which appears in small type in the bottom right corner, in the place where an artist might be expected to sign a painting. Avon thought—probably correctly—that Nin’s name would not help sell books.

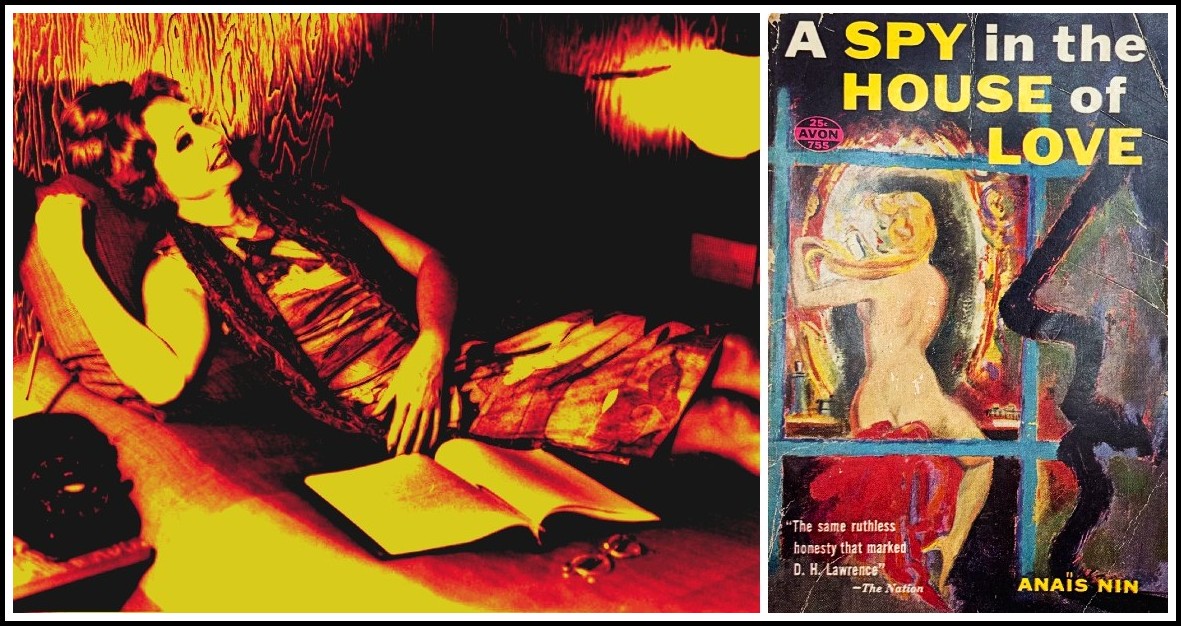

Anaïs Nin (colorized) | Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1957 front cover

The back cover continues the sexual emphasis of the front cover. Another quotation from The Nation comes first: ‘A manual of love’s subterfuges.’ Below it, a picture of a blonde’s head, mouth open suggestively, with her face crossed by three bars, two red and one yellow, with obvious phallic implications. Then, some breathless prose: ‘Brilliant, remorseless, unashamed and utterly honest—this is the story of Sabina and her relationship to five different men: her husband—and four others.’ At the bottom of the back cover appears a picture of Nin holding a cat to her face (the implication of ‘pussy’ cannot be missed) and a two-sentence statement about her, some of which is misleading if not inaccurate. Nin was not then ‘universally acclaimed as both poet and novelist’. In fact, she was universally acclaimed for nothing, and she never was a poet. The Avon edition of Spy illustrates how important cover art can be in generating sales. According to Nin, this edition sold 170,000 copies. Pity the person who bought it expecting a hot read and found instead a psychological study of a character named Sabina.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1957 back cover

V. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: BANTAM BOOKS

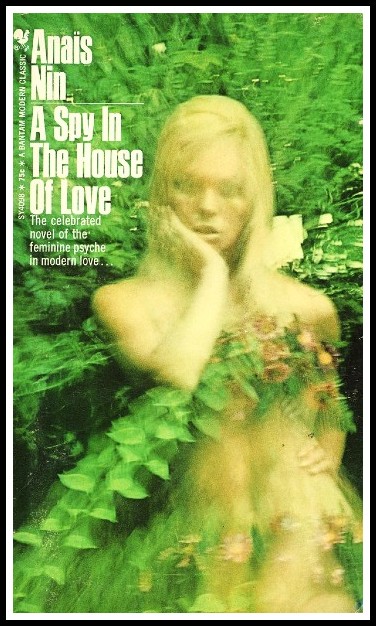

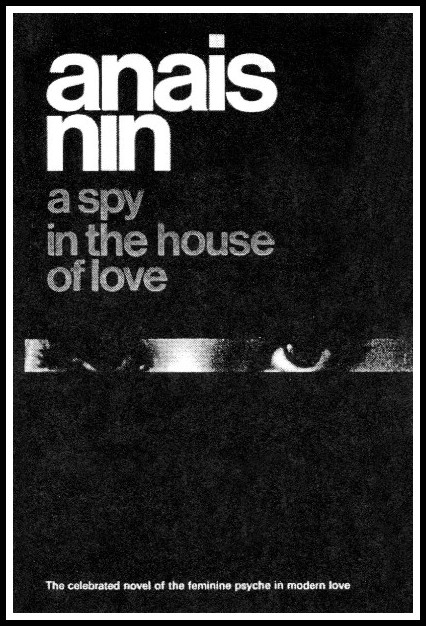

Following the low-budget 1966 Swallow edition which mostly follows the design of the British Book Centre dusk-jacket, discussed above, Bantam published the next edition of Spy in 1968. This is the first edition to be published after the success of the first two volumes of the Diary. Perhaps as a result of her recent popularity, Nin’s name appears first on the cover; but, in truth, it does not attract the eye, nor does the title, which emphasizes no words over others. The eye notices instead the cover art, which is a photograph of a blonde, apparently naked in a green setting in nature, with left arm akimbo and right hand cupping her right jaw. She looks come-hitherish. She resembles Eve after the Fall, or a flowerchild in the age of free love. The photograph is out of focus. A close examination of the picture reveals that the woman is not naked, that her breasts and groin are covered by flower-bedecked garments. In viewing the picture casually, however, one would think the flowers part of the foliage. So how does this picture connect with the novel, if at all? There is no sense of a house of love; and if spying occurs, it is the photographer spying on the woman, who sees him and is not embarrassed by his presence. But the picture also represents the character of Sabina fairly faithfully. Here is a sexual woman pondering something, such as her own identity, as Sabina does in the novel. And having the picture out of focus suggests the uncertainty Sabina feels about herself. The words under the title reinforce this view: ‘The celebrated novel of the feminine psyche in modern love.’ How celebrated this novel was in 1968 is open to question.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1968 front cover

The back cover emphasizes Nin’s seriousness and legitimacy, most obviously by noting that her novel is ‘A Bantam Modern Classic’. It notes other such classics, including books by Sartre, Lawrence, Kazantzakis, Gide and Malraux. Some company. From the Bantam point of view, then, Nin had arrived. The text on the back cover quotes Lawrence Durrell, Henry Miller, The Atlantic and Newsweek; all the quotes are serious and non-sexual in nature. The blurb reflects Sabina’s problem—her ‘fevered quest for fulfillment which drives her from lover to lover, through harrowing guilt and deception, toward a final imagined consummation’—although it also encourages potential purchasers of the book to think it focuses on the adventures of a nymphomaniac. Unlike Avon, the first mass-market paperback publisher of Spy, Bantam crafted a cover design fairly faithful to the plot of the novel, despite the picture of the woman on the front cover which might lead the casual observer of the book to conclude that Spy is a sexy novel. This design apparently succeeded in attracting readers, because Bantam offered a second printing with identical cover art during the month it was first published, April 1968.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1968 back cover

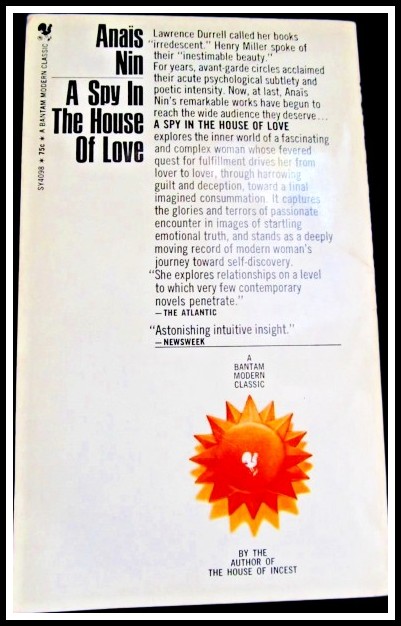

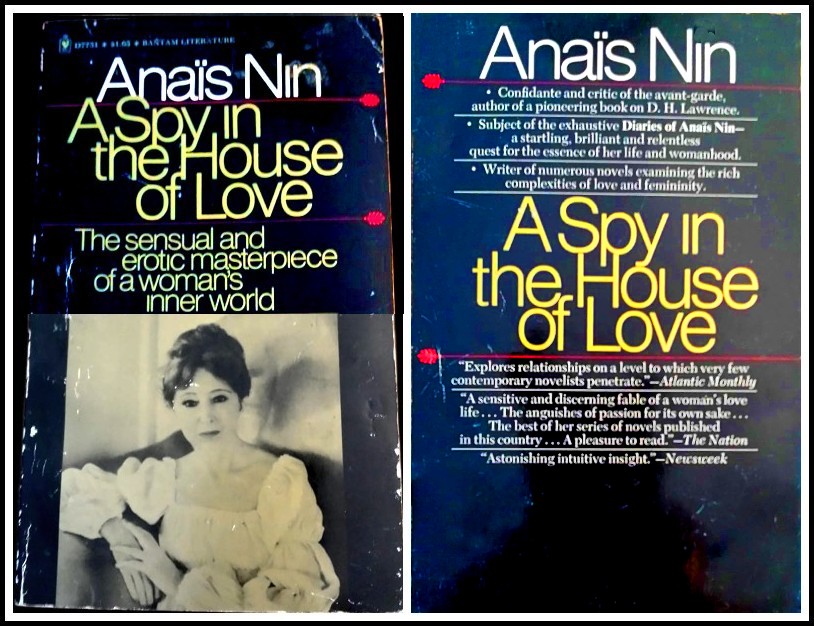

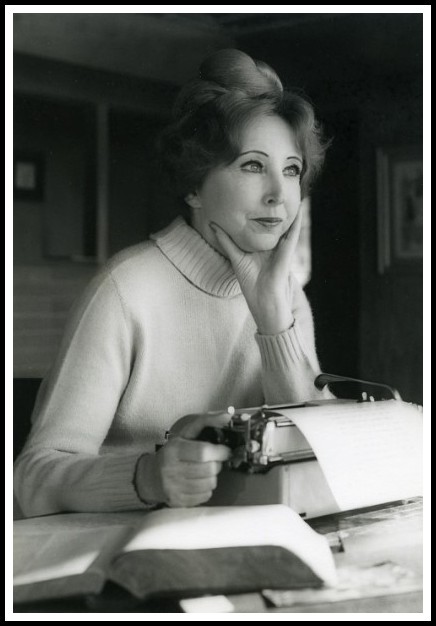

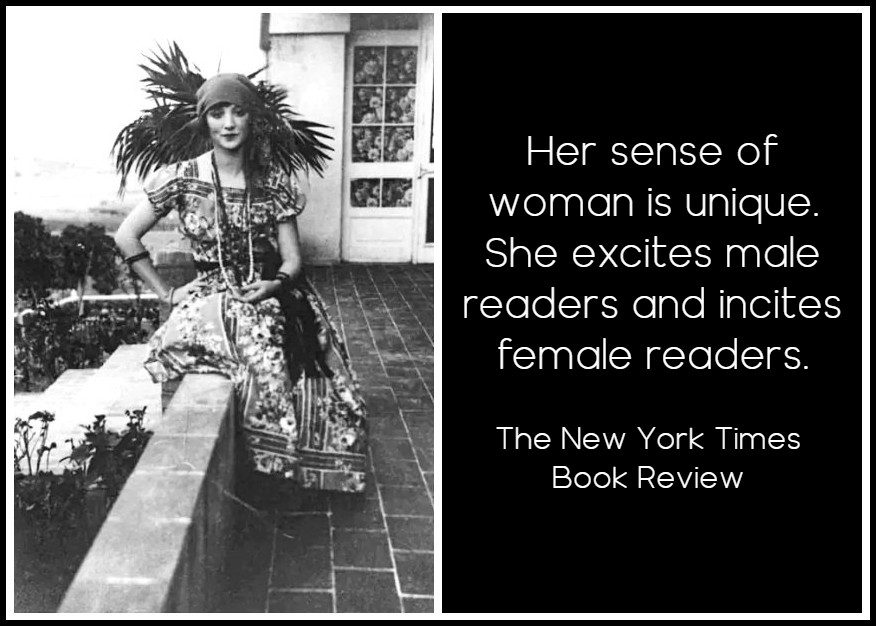

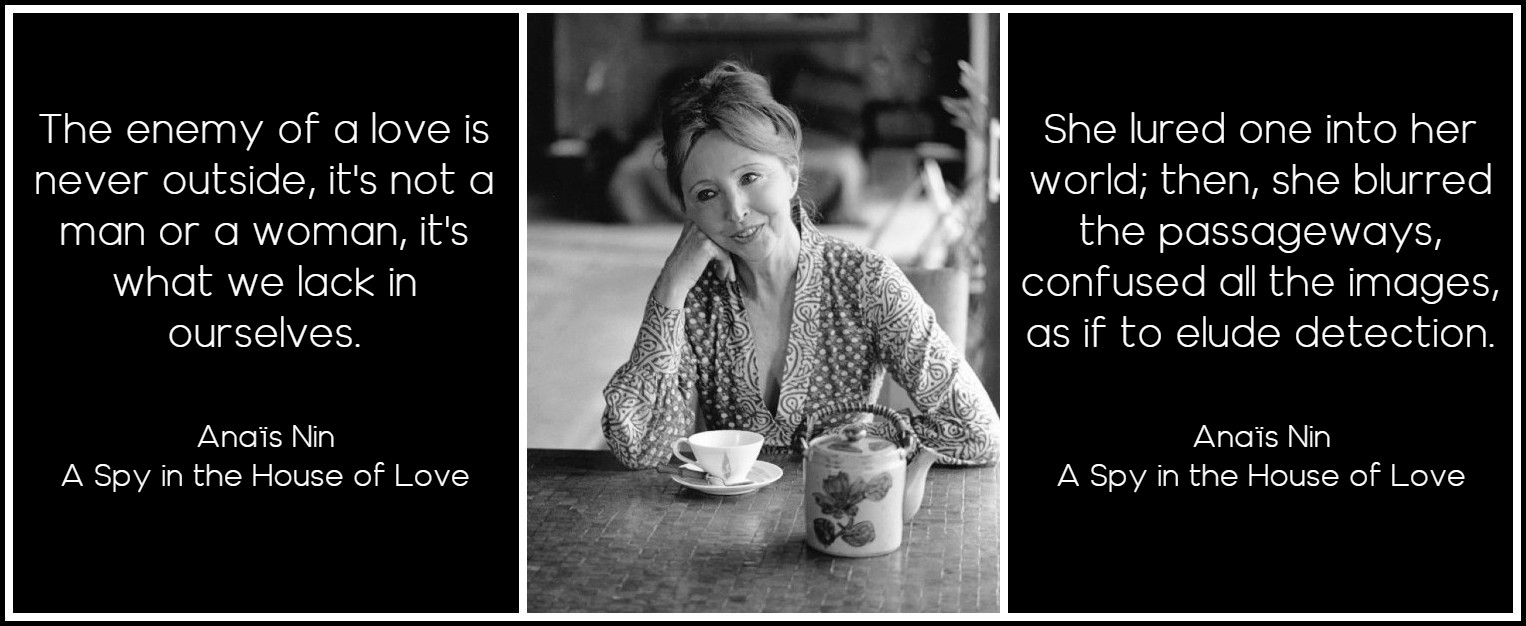

No third printing was called for, however, until September 1974, at which time Bantam published Spy with new covers. Because all the printing except the author’s name is gold on black (with two thin parallel lines in red), Nin’s name in white immediately catches the eye. By this time, five volumes of Nin’s Diary were in print, so Nin had attained a popularity that made her name marketable. If further proof were needed to support this claim, the picture on the front cover makes the case. It is not a sexy woman tempting unsuspecting male readers to buy the book; rather, it is Nin herself in a photograph taken by Marlis Schwieger. Although Nin looks relaxed, the picture is formal. Finely coiffured, eyes made up, right arm resting on the arm of a chair, Nin appears attractive and serious, despite the mild sexual suggestiveness of her squared scoop-necked dress. If her name and picture did not persuade prospective readers to buy the book, Bantam attempted to attract them by the words above her picture: ‘The sensual and erotic masterpiece of a woman’s inner world.’ The important words are ‘sensual’, ‘erotic’, and ‘masterpiece’, which convey that this is both a serious and sexy book. If the front cover does not fully capitalize on the novel’s title, neither does the back cover. There, blurbs focus on Nin as a serious author (of a book on Lawrence, of novels, and of her Diary); it includes quotes from Atlantic Monthly, The Nation, and Newsweek.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1974 front and back covers

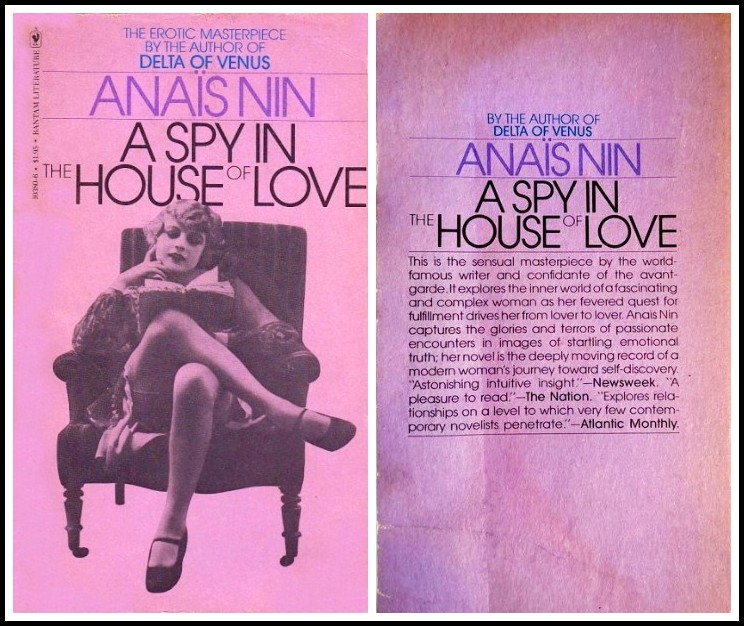

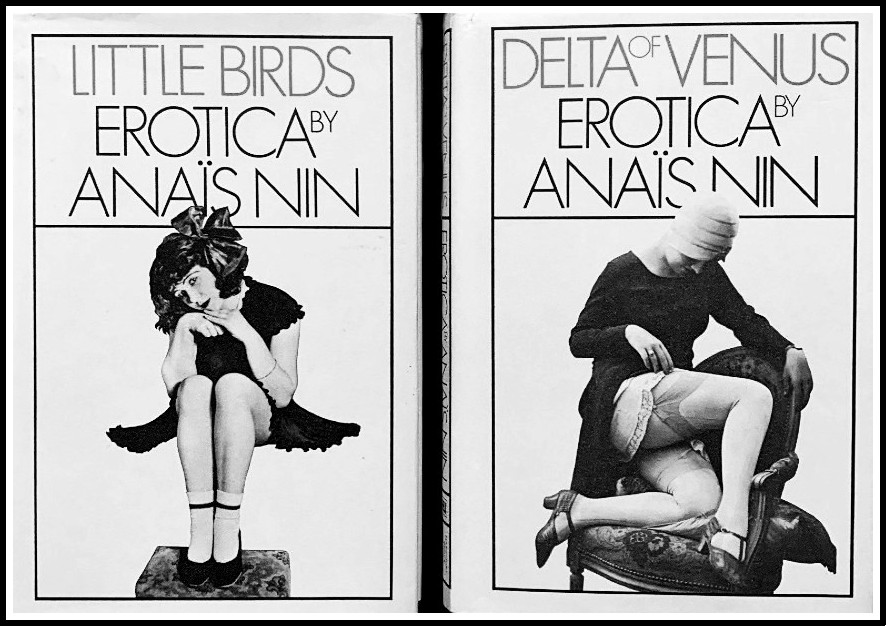

Bantam twice packaged Spy without exploiting its title. But when new cover art was called for in 1978, Bantam could not resist emphasizing the sexual, and not only because the title lends itself to such a treatment. Nin died early in 1977. Soon thereafter, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich published Delta of Venus, a volume of erotic stories Nin had written in the 1940s. It was a smash, a bestseller. (Another volume of erotica, Little Birds, appeared in 1979; it also sold well.) As a result, Nin, who had become fairly widely known as the author of her Diary, became something of a posthumous celebrity as one of the first women to write erotica. Because of this new fame, Bantam presented Spy as similar to the erotica. On the lavender front cover, the skyline (the space above the author’s name) reads: ‘THE EROTIC MASTERPIECE BY THE AUTHOR OF DELTA OF VENUS.’ While clearly visible, Nin’s name is not so pronounced as on earlier Bantam covers because its shade of lavender is only slightly darker than the dominant colour. The black-lettered title is more prominent than Nin’s name. But the photograph attracts the eye. This picture from the Bettmann Archive shows a woman reading in an armchair. Looking both pensive and mildly amused, she appears to be engrossed in her book. The position of her legs indicates that the book is causing her to become sexually aroused. Her right calf rests on her left knee; her skirt is above her stockings. The eye is therefore drawn immediately to the dark area at the rear of her right thigh, the area above her stocking, near her genitalia. Clearly, the designer intended the blurb and picture to suggest the sexual nature of Spy. The back cover is less obviously exploitative than the front one. It states that Spy is ‘BY THE AUTHOR OF DELTA OF VENUS’ and refers to Sabina’s ‘fevered quest for fulfillment’. It also contains the familiar quotations from Atlantic Monthly, The Nation, and Newsweek.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1978 front and back covers

Bantam would have had to exercise great restraint not to present Spy as an erotic novel in the late 1970s. People were buying, reading and buzzing about Nin’s erotica. Further, Bantam had published the paperback edition of Delta of Venus at the same time as this printing of Spy, June 1978. Despite the fact that the picture on the volume of erotica is from the collection of Richard Merkin and not from the Bettmann Archive, the two covers convey a similar sexy tone. Clearly, Bantam wished to connect the novel with the erotica in readers’ minds so as to increase the sales of the former, since the latter was almost guaranteed substantial sales. Finally, in July 1982, Bantam published Spy as a Windstone edition with the same front cover of a woman reading a book. The back cover, while containing the text just described, changes the colour from lavender to white and reproduces a reversed image of the woman reading, as well as the Windstone logo. In presenting Spy as it did with this, its third cover (with variations), Bantam wished to enhance sales by associating it with Nin’s erotica.

Anaïs Nin, Little Birds & Delta of Venus, covers

VI. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: PETER OWEN

In 1971, the second English edition of Spy appeared under the imprint of Peter Owen. While the dust-jacket of the Neville Spearman first English edition blatantly emphasizes sex, by means of a bust of a woman, the Owen dust-jacket art is much more subtle. The black front cover has Nin’s name in white and the title in turquoise. All lettering is lower case, with no word in the title emphasized over any other. What makes the cover so striking is the appearance of a woman’s eyes looking through what appears to be a peep-hole in a door. Although her right eye is barely visible, the left one is focused on something or someone on the other side of the panel or door behind which she stands. On what? On whom? Is she on the inside looking out? Or on the outside looking in? What is in? What is out? Certainly, though, she is eyeing the person who is looking at this dust-jacket. At the very least, she is involved in something illicit. She is probably on the inside looking out, with the inside being a brothel and the person at whom she is looking being a prospective patron. She seems to be asking, ‘Is he safe? Is he the law?’ But in keeping with the character of Sabina, this woman is in all likelihood looking into the troubled area which is her psyche. Blackness perfectly conveys the nature of Sabina’s tormented, ill-defined inner self. In this case, the eyes represent the woman’s external reality; the blackness, her internal. The words at the bottom of the cover allow for this interpretation: ‘The celebrated novel of the feminine psyche in modern love’, words originally used on the first Bantam paperback in 1968. Within the context of this cover, the most important word is ‘psyche’. The Peter Owen jacket design by Keith Cunningham is therefore both provocative and accurate.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1971 cover

The back of the dust-jacket includes a photograph by Christian du Bois Larson of Nin at her typewriter, left hand cupping her left jaw, practically the mirror image of the model on the 1968 Bantam cover. She appears serious, smart and stylish. The jacket text contains three paragraphs of solid, unspectacular biographical information about her. In sum, the back cover was designed to appeal to the serious reader, as were the flaps. The front flap summarizes the plot succinctly and contains blurbs; the back flap notes other Nin works, with blurbs. Cunningham designed the dust-jacket to appeal primarily to readers who might be interested in psychological fiction, and not necessarily to readers interested in erotica, although the front cover allows for a sexual interpretation.

Anaïs Nin

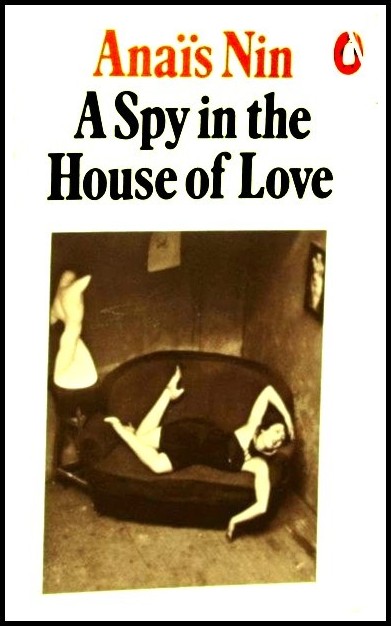

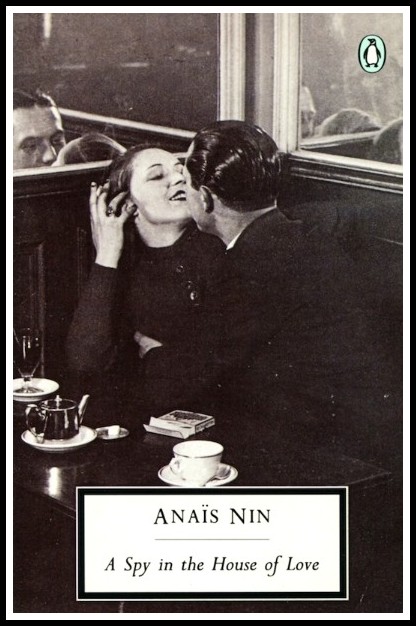

VII. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: PENGUIN BOOKS

The first Penguin printing (1973) of Spy has a white cover with Nin’s name in brown and the title of the novel in black. In the upper right corner appears the publisher’s logo, a penguin on an orange background. The lettering and the logo are simple, direct, classy. But the cover also includes a photograph by André Kertész which raises questions.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1973 cover

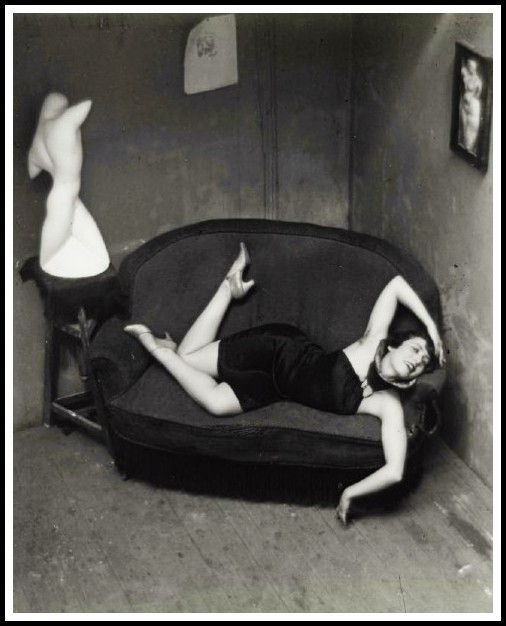

If only because of the composition of the picture, one would know it is the work of a master photographer. It is balanced, symmetrical and provocative. It is also bizarre. A woman reclines awkwardly on a couch. With her arms and legs creating a shape resembling a swastika, she cannot be comfortable. So why has she assumed this position? Why is she dressed as she is, in a dark strapless dress or slip to which is attached a neckpiece resembling a harness? And what to make of the images which surround her: a sculpture of a naked man, a painting or photograph of a sculpture of a naked woman, and an indecipherable picture between them on a wall? The sexual implications of all of this indicate either that she is masturbating with her thighs or reclining languorously in a brothel, or both. Her facial expressions indicate that she might be experiencing an orgasm. The raised upper right arm of the male sculpture (it has no lower arm) points toward the female sculpture in a manner suggesting an erection. This photograph is sexually charged. The scene appears to be a house of love, and someone (the photographer) is spying on the woman. It therefore emphasizes the sexual possibilities of the title of Nin’s novel. But the woman might just as easily represent Sabina using sex (with her lovers) to find love and completion as a human being, goals she fails to attain. That is, Kertész’s picture is not out of keeping with the novel’s title or its main character’s psychological state.

Andre Kertész, Danseuse burlesque, Paris; 1926

Although the back cover offers an otherwise ordinary description of Nin and the novel, it includes the now-familiar words ‘celebrated’ and ‘modern love’. It also quotes from reviews in the Los Angeles Times and the New York Times Book Review. The cover design of this Penguin printing—which is also used on the next six printings—is, then, with the exception of Kertész’s photograph, a serviceable, unspectacular cover far removed from such a cover as that of the Avon edition. But the picture, which is the focal point of the front cover, emphasizes the sexual content of the novel.

Anaïs Nin in Cuba

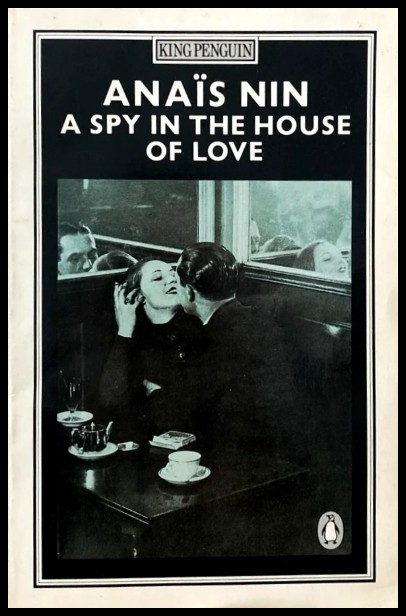

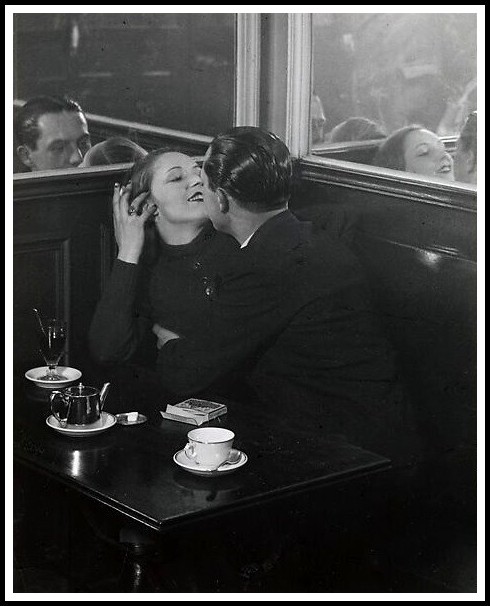

When Penguin next printed Spy, in 1982, it appeared in the King Penguin series with different cover art. (This series also included Under a Glass Bell, Nin’s collection of stories, as well as works by John Cheever, D.M. Thomas, Shirley Hazzard and others.) The cover is striking. Significantly larger than Kertész’s photograph is one by Brassaï from the early 1930s. It shows a man and woman in a corner booth at a café. She is against the wall, and he is next to her; their lips almost meet. He appears to hold her right breast with his left hand (he possibly touches her just below and to the side of the breast); she smiles. An empty cup pushed away from them indicates that they have been there for some time, and one may assume, given her wine glass and an open box of cigarettes, that they are not rushed. They enjoy each other; the scene is mellow. Once they leave the café, they will doubtless engage in sexual intercourse. While not a picture of a house of love, it is a picture of a booth of love. In selecting this Brassaï photograph to attract readers to Spy, Penguin chose wisely. Not only is it a wonderful picture, but it possesses a sexiness in keeping with the novel’s title while suggesting Sabina’s psychological turmoil. But the rectangular cover design—which is similar on all King Penguin books—enhances the effectiveness of Brassaï’s photograph. The fragmentation motif is reinforced by the appearance of rectangles within rectangles. The outer one is white, within which are two black lines alternating with two white lines. Then comes a large black rectangle containing Nin’s name and the novel’s title; the name of the series (King Penguin) appears in the smallest rectangle. Such a layering arrangement further depicts Sabina’s troubled state by symbolizing her inner selves.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1982 cover

But the picture contains more. The lovers’ images are reflected in mirrors directly above the booth. Because the mirrors form a right angle, the man’s face (from the nose up) is visible in the left mirror while one side of the woman’s face is visible in the right one. The right mirror also reflects, from the other mirror, a third angle of vision on the couple; the left one reflects an image from the right mirror, although the image is indistinct. This amazing photograph therefore captures several aspects of the lovers. We see more of the woman than of the man. Her images make possible a composite view of her face. Her neck, right forearm and buttoned sweater are visible, as is her right little finger, which is positioned in her right ear; she holds a cigarette. One sees considerably less of him: only part of his face and the rear and left side of his head. His suit blends in with the dark booth. He has recently had his hair cut. This photograph accurately depicts Sabina in her quest for love and self-fulfilment. Her image is fragmented; we see four different images of her, images which combine to create a complete impression of her face but which do not, when taken together, constitute the whole woman. Although we see much of her, we see nothing below her breasts. She remains an undefined woman of parts, as does Sabina. But who is the man? What do we know of him? He remains mysterious, undefined. His three different images reveal little about him. He therefore might be seen as representing the lovers Sabina takes (Philip, Mambo and John) in her difficult effort to gain wholeness. Although the back cover continues the rectangular design of the front cover, it uses the same blurb and review quotations as the 1973 Penguin printing. Especially in the context of the front cover with the Brassaï photograph, the back cover seems plain and straightforward.

Brassaï, Couple d’amoureux dans un café parisien, 1932

But Penguin was not finished tampering with the cover of Spy. In early 1991 it published the novel as part of the Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics series. Here, the Brassaï photograph consumes the entire front cover, extending to all edges. Nin’s name and the title appear in a white rectangle at the bottom of the cover, just below the cup and saucer in the picture. The result is immediately obvious: because the lovers appear closer to the viewer than on other covers, they are considerably larger than previously. The focus is solely on them, thus emphasizing their eroticism and therefore the eroticism of the novel itself. It does so at a cost: it does not include the woman’s face reflected in the right mirror, which is present on the earlier Penguin covers. Gone, then, is any serious effort to have Brassaï’s photograph suggest as fully as possible the nature of the novel’s contents. A voyeur would delight in this unaltered view of unselfconscious lovers. The back cover slightly alters the plot summary of the Penguin Modern Classics printing. While it retains the usual review excerpt from the New York Times, it adds another from the same newspaper (by Wallace Fowlie); it deletes the Los Angeles Times review. It includes, though, two sentences by Gore Vidal, an early Nin booster.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1991 cover

Penguin took Spy cover art and design seriously. It used pictures by master photographers Kertész and Brassaï, and it presented the latter’s photograph with three different cover designs. With a total of four different cover designs, Penguin offered this novel in more ways than any other publisher.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1985 cover

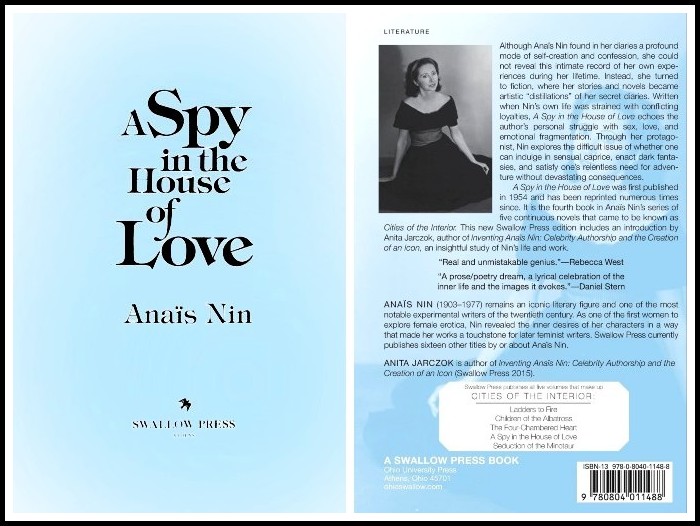

VIII. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: SWALLOW PRESS

In 1984, the same year as the most recent Penguin edition, the Swallow Press changed its cover design, which had been that of the British Book Centre edition since Swallow published the novel of 1966. The new, sky-blue Swallow cover is simple yet eye-catching. Nin’s name is in black; the title, in white, with the words ‘Spy’ and ‘Love’ in larger type than the other words. The cover also includes Paul Bradford’s sketch of a firebird’s head in the manner of a 1942 sketch by Ian Hugo, which has appeared on the half-title page of all Swallow printings. In the novel, a firebird serves as a symbol for Sabina. The back cover, in keeping with Swallow practice since 1966, includes only the titles of Swallow’s Nin books and a few blurbs. This is a serviceable, unexploitative cover, which was used again in the Swallow printing of 1987. In 1991, the publisher kept the same cover design but changed the predominant colour from blue to what the press calls lipstick-pink. A barcode replaces the Swallow device, publishing copy and D.H. Lawrence blurb on the back cover. The next Swallow printing (1992) has this same cover design.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1980s front & back covers

In 1995, this publisher used another cover. The wrappers are violet, with a photograph of an exotic-looking Nin dominating the front cover. The popular perception of Nin at this time was primarily as a wild woman because of revelations in three volumes of her supposedly unexpurgated Diary. The front-cover picture of her in a veil, with an ornament in the centre of her forehead—a veiled harem dancer—invokes this unrestrained aspect of her, suggesting and exploiting her mysteriousness, her adventurousness, her sexiness. On this cover and the spine, the words ‘Spy’, ‘House’ and ‘Love’ are orange-red; the other words in the title, black. The author’s name appears in white on a triangle outlined in black; the cover notes that this printing has a foreword by Gunther Stuhlmann. The back cover includes a black-and-white picture of Nin looking demure, several sentences about the novel, an advertisement for Cities of the Interior (on an orange-red background) and a barcode. Because of its colours and the dramatic picture of Nin, this is by far the most striking Swallow/Ohio University Press cover.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love, 1995 cover | Two colorized photos of Anaïs Nin

IX. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: POCKET BOOKS

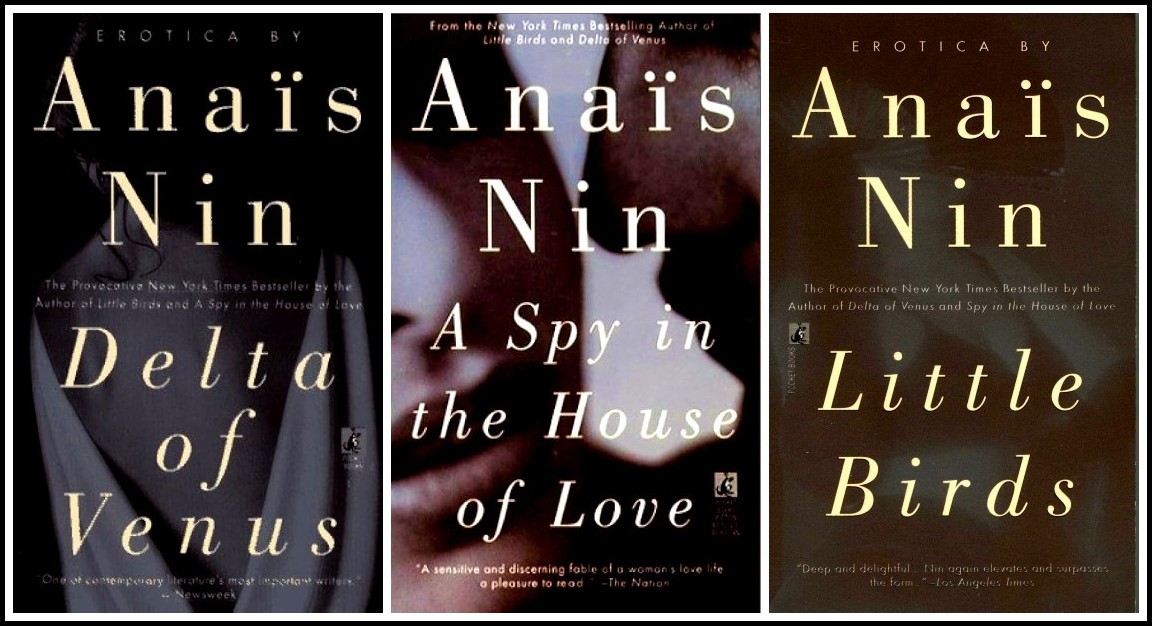

Pocket Books succeeded Bantam as the United States’ mass-market paperback publisher of Spy, Delta of Venus and Little Birds. This firm published the volumes of erotica in 1990, but not until 1994 did it publish the novel. In October 1994, it published Delta of Venus and Little Birds with covers different from those of the 1990 printings but similar in style and mood to the cover on its edition of Spy. Through its use of cover art and design, Pocket Books wished book buyers to think of the three books as a package and of the content of Spy as therefore similar to that of the erotica. The front cover of the Pocket Books Spy offers this: ‘From the New York Times Bestselling Author of Little Birds and Delta of Venus’, thus reinforcing the cover art connection between the novel and erotica, as Bantam had done. The largest print is given to Nin’s name, thus indicating that Pocket Books thought her name could sell books. Following the title is a quotation from The Nation: ‘A sensitive and discerning fable of a woman’s love life… a pleasure to read.’ All printing is superimposed on an out-of-focus detail from a close-up photograph of the heads of a man and woman. Little more than half of her face is visible; we can see only his nose and lips. Her lips are parted slightly; his nose almost touches her cheek. He seems about to say something meaningful to her. They suggest intimacy, which may or may not be sexual. The back cover includes quotations from The Atlantic (the one used in the Bantam printings) and Newsweek, as well as a summary of the plot. With the exception of connecting the novel with the volumes of erotica and the possible implication of a sexual relationship between the woman and man in the photograph, the cover art on this mass-market paperback is surprisingly restrained.

ANAÏS NIN: Delta of Venus | A Spy in the House of Love | Little Birds | 1990-1994 covers

As of this writing (early 1996), the Nin novels which have had the greatest number of American and English publishers, other than Spy, are Ladders to Fire, Children of the Albatross and The Four-Chambered Heart, with four each; Seduction of the Minotaur and Collages have each had three. Eight different publishing houses have published Spy, with at least four of the editions requiring more than one printing: Neville Spearman, Swallow, Bantam and Penguin. Four mass-market paperback publishers have seen the sales potential of Spy: Avon, Bantam, Penguin, and Pocket Books. No other Nin novel has attracted any American mass-market paperback publisher, although, in England, Penguin has published Children of the Albatross and Seduction of the Minotaur, both in 1993. English publishers with more modest distribution than Penguin have also published Nin novels in paperback: Peter Owen has published Ladders to Fire (1991); Virago, The Four-Chambered Heart (1992) and Collages (1993). With the exception of Collages, Nin’s novels are of a piece. Nin thought of them as her continuous novel and published them under the collective title of Cities of the Interior in 1959. The reason for Spy’s popularity stems, therefore, not primarily from its literary quality but rather from its title, which permits publishers to present it as a sex novel, thus increasing the likelihood of sales. Some of the publishers have exploited this potential through cover design, which includes suggestive if not erotic drawings or photographs. The trend began with the Neville Spearman edition of 1955, reached its zenith with the Avon edition of 1957, and continued in less dramatic fashion with the first (1968) and third (1978) Bantam covers and all four Penguin covers (1973, 1982, 1985, 1991). Clearly, sex sells.

Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love

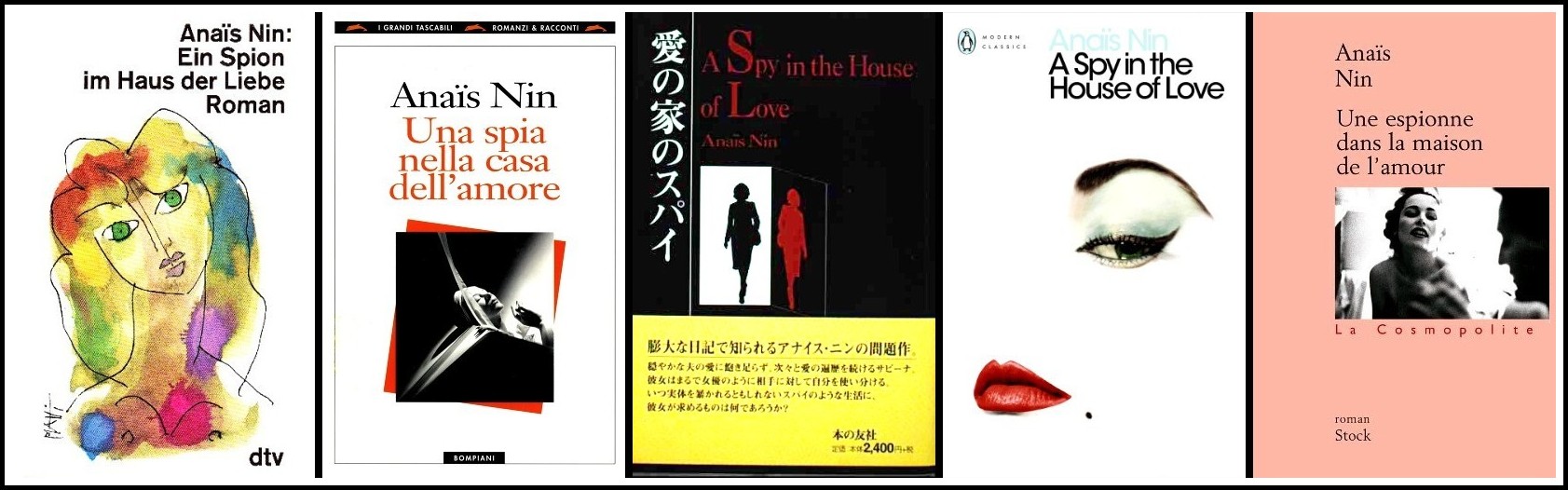

X. A SPY IN THE HOUSE OF LOVE: FIVE OTHER COVERS

German, 1983 | Italian, 2014 | Japanese, 2000 | British, 2001 | French, 2003

THE SPY

Jim Morrison | The Doors

I’m a spy in the house of love

I know the dream that you’re dreaming of

I know the word that you long to hear

I know your deepest, secret fear

I’m a spy in the house of love

I know the dream that you’re dreaming of

I know the word that you long to hear

I know your deepest, secret fear

I know everything

Everything you do

Everywhere you go

Everyone you know

I’m a spy in the house of love

I know the dream that you’re dreaming of

I know the word that you long to hear

I know your deepest secret fear

I know your deepest secret fear

I know your deepest secret fear

I’m a spy

I can see you

What you do

And I know

STEVEN JEZO-VANNIER ON ‘THE SPY’

From Steven Jezo-Vannier, The Doors: Ship of Fools (Marseille: Le Mot et le Reste, 2017) This excerpt freely translated from the French by Richard Jonathan.

A shaman and a voyager between the material and the spiritual worlds, Jim plays with the linearity of time. Present at the dawn of the world, he ignores boundaries, including those of the mind. This is what he suggests with ‘The Spy,’ in which he plays a spy (no doubt the same one who watched Pam in ‘Love Street’). Initially, Jim titled his lyric ‘The Spy in the House of Love,’ borrowed from the title of a novel by Anaïs Nin, A Spy in the House of Love. An American writer born in Paris to a Cuban father, she distinguished herself by the freedom and quality of her writing, nourished by the eroticism of her libertine liaisons, notably with Henri Miller. In the novel, Nin addresses the possibility of feminine self-affirmation through a heroine living a lie to escape the responsibilities of reality. Jim was marked by his reading of the book, whose psychoanalytic value Nin does not hide. He sings the words in a voice that is calm, measured, and self-assured. The shaman has become a clairvoyant. He photographs souls, as he did in ‘My Eyes Have Seen You’. He uncovers hidden feelings, pierces unspoken desires, and exercises mastery of emotions; he exudes a strong sensuality and exercises a hold over his audience. Through the music, his voice penetrates the listener, provoking a shiver of anxiety. The power of suggestion operates through this subtle cocktail of induced sensations. The musical arrangement amplifies the effect by creating a disturbing atmosphere in which anxiety blends with desire. Minimalist, Krieger’s guitar sets the scene from the very first notes. Manzarek plays a deep chord with a heavy left hand while the light right hand plays a catchy cabaret melody in an off-beat blues register. John uses his brushes on the snare drum and cymbals. The result is magnificent.

Jim Morrison | Photo: Jerry Hopkins

JOHN DENSMORE ON ‘THE SPY’

From John Densmore, Riders on the Storm: My Life with Jim Morrison and The Doors (New York: Dell Publishing, 1990) p. 234

Next we recorded ‘The Spy,’ which was fun for me because I got a chance to show off my jazz brush technique. We tried to create a mood for the song to complement Jim’s words. Putting heavy echo on Jim’s vocal enhanced his lyrics. The song showed a shrewd, voyeuristic side of Jim. Someone able to make love to a camera, perhaps. It was becoming easier to see the connection between our personalities and our music. Ray, with his professorial organ riffs; the lone-wolf-cowboy guitar howls of Robby; and me, blasting angry, coiled drum licks out of dead silence.

The Doors with producer Paul Rothchild | Photo: Paul Ferrara

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments