Teorema

Pier Paolo Pasolini, 1968

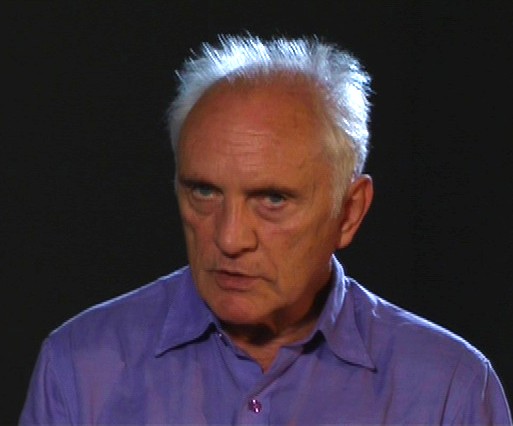

TERENCE STAMP INTERVIEW

ON ‘TEOREMA’, ON FELLINI AND PASOLINI, ON ACTING AND LIFE

Interviewers: Rossana Capitano with Morgaine Gaye

This interview with Terence Stamp appears as a bonus on the BFI DVD of Pasolini’s Teorema. It was conducted by Rossana Capitano with Morgaine Gaye in London on July 10, 2007. I have transcribed it verbatim, but have edited out hesitation markers (false starts, repetitions) and fillers (‘you know’, ‘kind of’, ‘like’) and occasionally made brief cuts for the sake of clarity and fluidity. I have also left out the questions (or integrated them into the answers), since the interview is largely a long monologue by Stamp with only the occasional prompt from the interviewers.

What’s interesting for me is how the movie came about. 1968 was a very crucial moment in my life. I’d had this very high-profile love affair with what turned out to be the world’s first supermodel, and it had ended badly. So I was not in particularly good shape emotionally.

And then I got this call from Fellini, or Fellini’s casting director. What had happened was that he’d written a part of an Edgar Allan Poe story for Peter O’Toole and Peter O’Toole let him down at the last moment. So Fellini called a casting director here in London and said, ‘Send me your most decadent actors’. And James Fox and I went. I had just finished a Western in Utah, where my hair had been dyed blonde and the roots were growing out. And I was like a flower child, I’d discovered grass and I was wearing flowers and ankhs and stuff. I went to Rome and Fellini took one look at me and it was love. It was mutual.

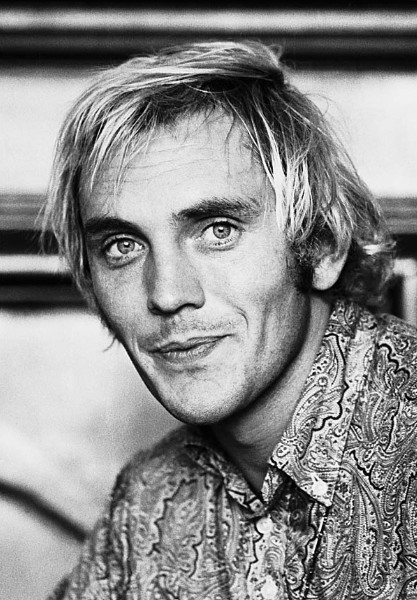

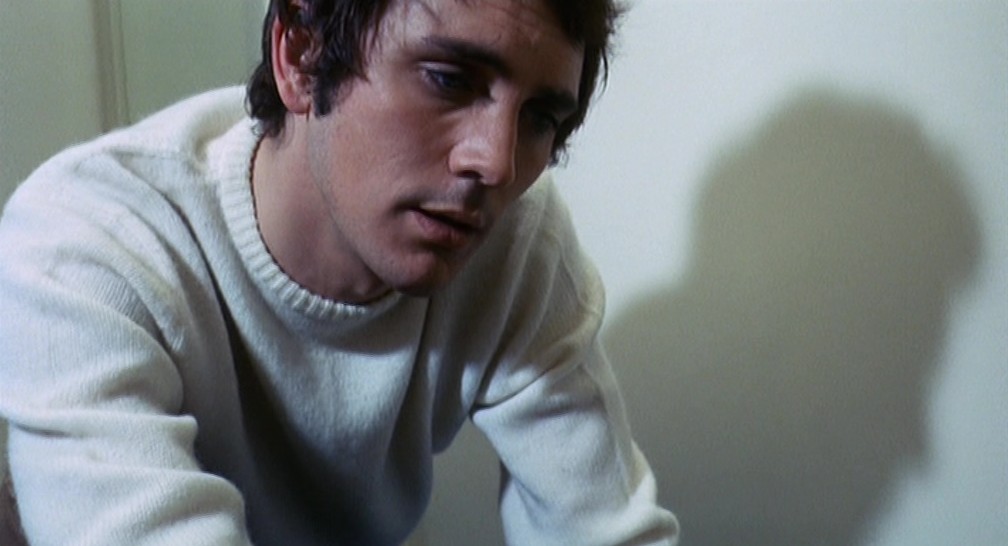

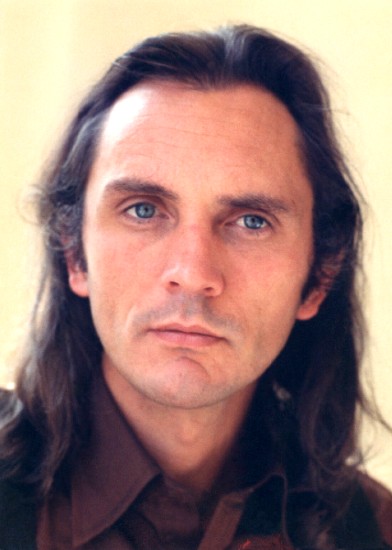

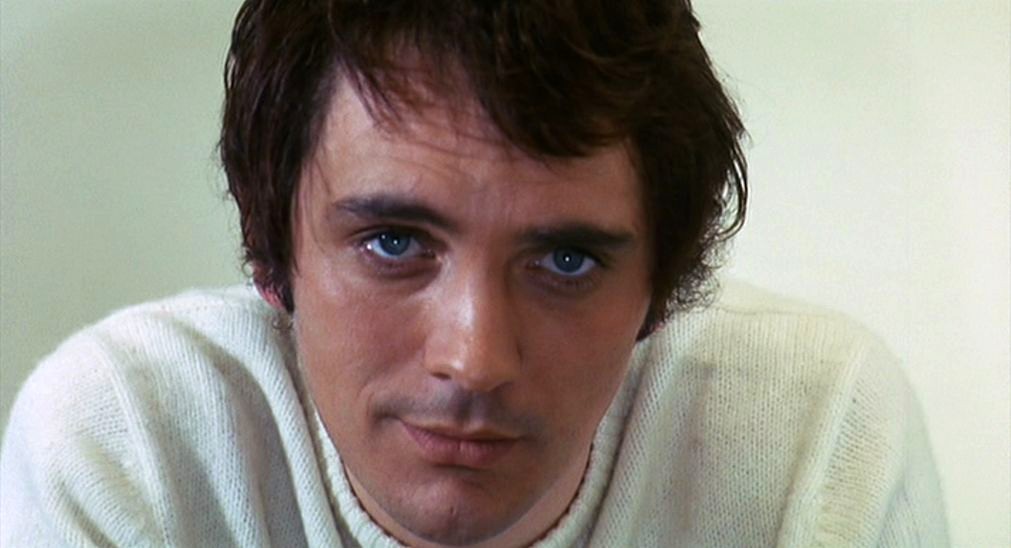

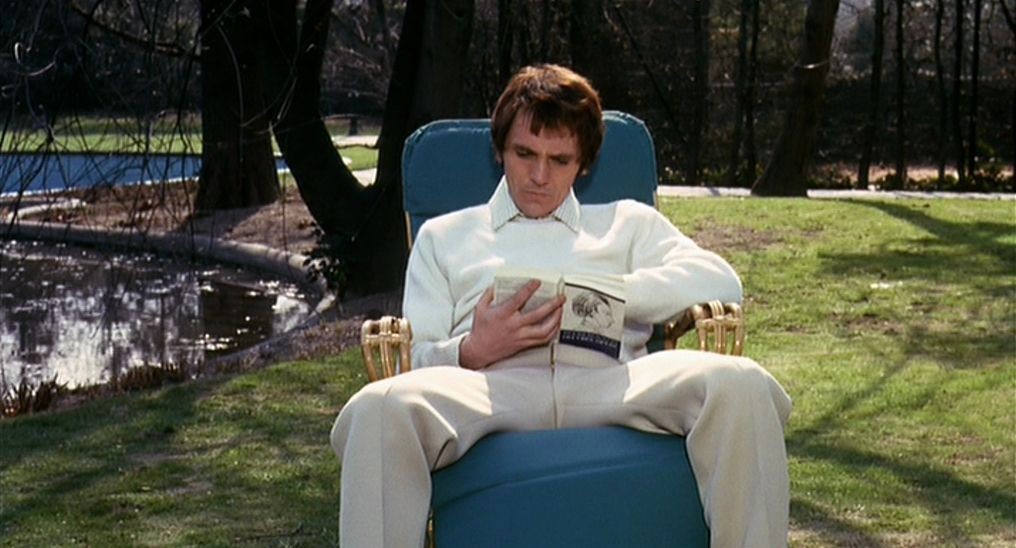

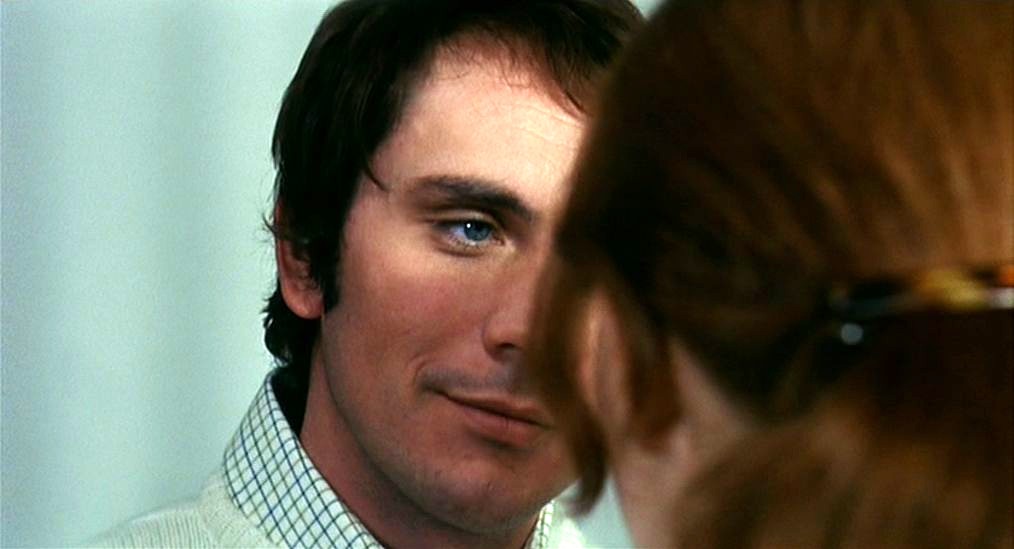

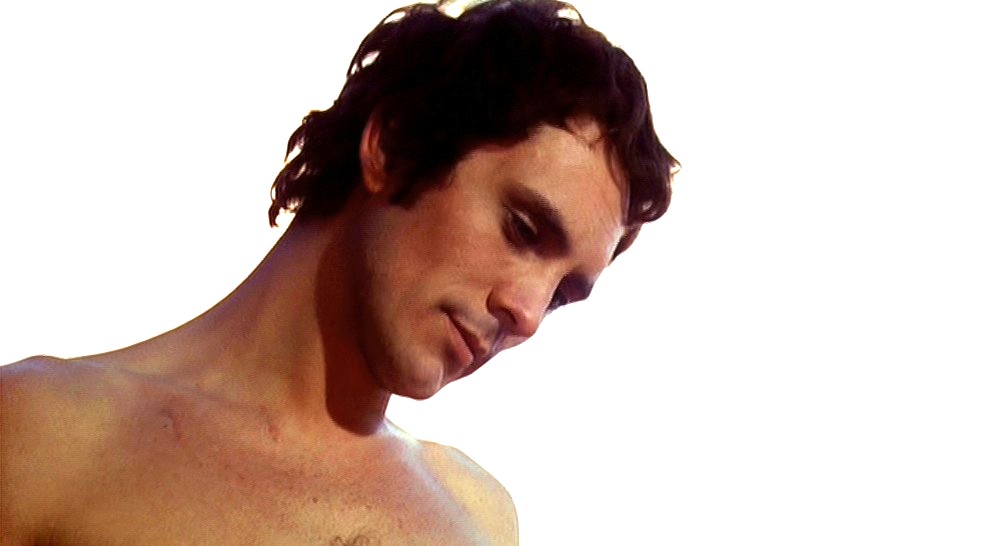

Terence Stamp in 1968 | Photo: Robert Walls

The way to describe Fellini? I remember saying to a spark on the set one day—I was trying to learn a bit of Italian—and I said, ‘Why do you like to work with the maestro?’ And this guy said, ‘Non è lavoro, Signor Terence. Vacanza.’ And it was true because during that movie, the fear that I’d had about making movies, which I’d always had—a sort of trepidation, a fear that something could go wrong between ‘action’ and ‘cut’—that just dissipated. I used to wake up laughing, I couldn’t wait to go to work. It was something to do with being chosen by Fellini, being Fellini’s first English actor to play a lead. And also, there’s a Sanskrit word, ‘satsang’, meaning ‘the company of the wise’. They say in India that certain illnesses can be cured just by ‘satsang’. I’m not saying Fellini was a sage, but there was something about his aura that was irresistible, that made you feel good about yourself.

So, most absolutely, the great experience of my life was working with Fellini. It was a peak in the way I was performing at the time. It was a real character performance I was giving because, since Toby Dammit was a completely decadent reprobate, I thought the best way to get the most from the Fellini experience was to do it straight. So I gave up smoking, I gave up drinking, and during the movie I became a vegetarian.

Terence Stamp | Histoires Extraordinaires (‘Toby Dammit’), Federico Fellini, 1967

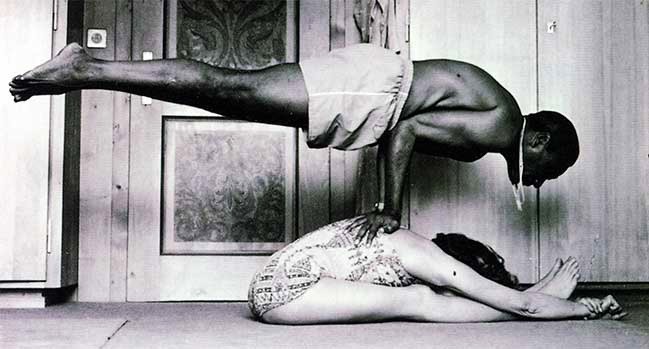

I also came under the influence of a lot of people that Fellini knew, in particular a great sage called Krishnamurti and a woman called Contessa Vanda Scaravelli. She was Krishnamurti’s yoga teacher, and consequently became my yoga teacher.

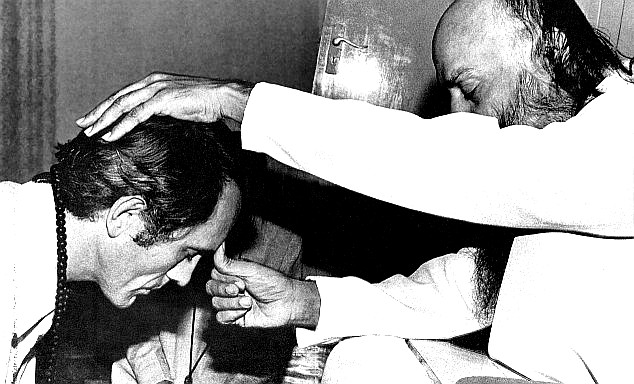

Vanda Scaravelli in ‘paschimottanasana’, supporting B. K. S. Iyengar

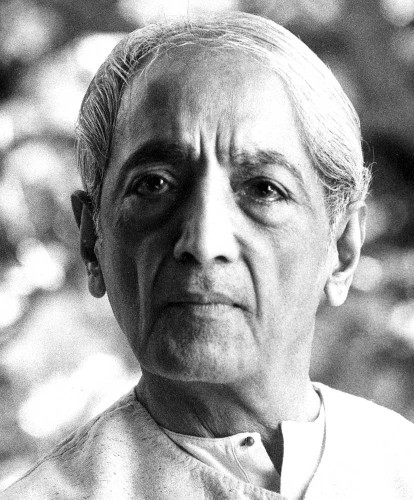

I remember being invited to lunch with Krishnamurti and everybody saying, ‘You must go! My God!’ I said, ‘Why? What’s so special?’ They said, ‘Well, he’s enlightened.’ I said, ‘What’s that? What does that mean? What’s “enlightened”?’ They said, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll understand.’ And then when I met him and sat opposite him at lunch, I just knew I had never come across anybody like that before. He was just exquisite. And he took me out for a walk and he talked to me, and I talked a lot, I talked at him, and he said things that I didn’t understand. But I had the feeling that he had kind of lit a straw and many years later the whole haystack burnt down, because my life did begin to change after that meeting with him. He gave me an intellectual understanding that you could live your life being asleep or you could live your life being awake. And the Pasolini thing did sort of coincide with that. I didn’t really put it together at the time, it was only afterwards that I thought to myself, ‘that’s what Krishnamurti is talking about.’ Because Krishnamurti said things like, ‘Be aware when you’re unaware.’ How could you understand that? ‘When the eagle flies, it leaves no mark.’ It was just beyond me.

Krishnamurti

And during the film with Fellini, something happened to me. I lost my fear of performing. It was something to do with being under the influence of Fellini. And at the end of the movie, Fellini asked me to go back to Rome to do a couple of lines of voice-over at the beginning of the ‘Toby Dammitt’ movie. And my brother Chris, who had just successfully signed The Who—he was making his own way in rock and roll—wanted to meet Fellini. So I took my brother Chris with me. So we were in Rome together.

Parallel with this is a story of my own life where I had come up to Oxford Street when I was about 12. I would come up to the West End to see unusual movies. And I had seen a movie called Bitter Rice, ‘Riso Amaro’. And I had fallen madly in love with the 17-year-old Silvana Mangano. I had lots of night-time fantasies about Silvana Mangano. I’d been in love with Silvana Mangano for years. I’d never met her. I had no chance of ever meeting her. And when we were in Rome to do the voice-over for Fellini, my brother and I were walking down Via Fratina and I saw coming towards me Piero Tozi, who had done my costumes for the Fellini movie, with another guy and this woman who was very different from the hot pants and everything that I’d seen as a boy, but was unmistakably Silvana Mangano.

I was in shock. I remember touching the building next to me, to stop myself falling over. And Piero Tosi introduced me to Silvana. And she said, ‘He would be good for Pier Paolo’s film’. And I said, ‘Who’s Pier Paolo?’ And she said, ‘Pier Paolo Pasolini’. At that point, my brother’s nudging me. I don’t know Pier Paolo. And I say to her, ‘Are you in the movie?’. She says, ‘Yes. Yes, I am in the movie. You know, it’s Pasolini.’ That was the first meeting. As we leave, I say to my brother, ‘God, it’s Silvana Mangano. I can’t believe it’s Silvana Mangano’. My brother’s saying, ‘But it’s Pasolini, you berk. Mama Roma. Accatone. Pasolini’s great’. I said, ‘Yeah but she’s going to be in the movie!’

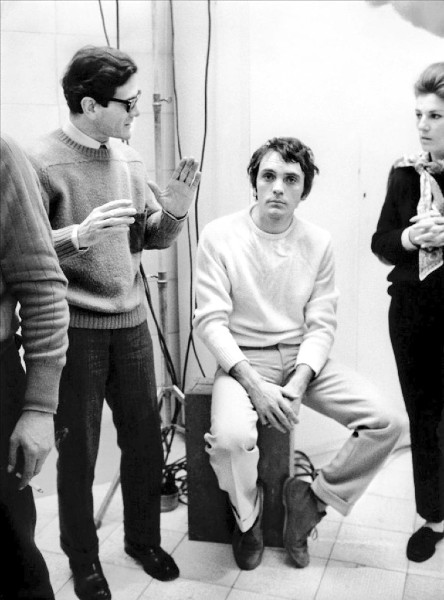

The next part of the story was about a month later. Pasolini, who didn’t speak any English, comes to London with the nephew of Roberto Rossellini, Franco Rossellini. They’re staying at the Claridge Hotel and they asked me to go and have breakfast with them there. I go. There’s this little guy, very gaunt, rather sort of frightening-looking. Doesn’t speak any English. He tells the story to Franco and Franco translates for me. And the story that I heard from Pasolini, via Franco, was that it is a story about a petit-bourgeois family in Milan—father, mother, son, daughter, maid. Into this household comes a guest. He seduces everybody and leaves. ‘This is your part’, Franco tells me. I said, ‘Oh, sounds like me. Is Silvana Mangano playing the mother?’ ‘Si, si, Silvana Mangano.’ That was how I came to do the movie.

When I worked with these great directors, I would invariably ask them, ‘How do you feel about directing? What’s a great movie for you?’ And it was very interesting when I asked Fellini. I asked him, ‘How do you feel about the film?’ And he said, ‘Listen, Terence, this film, it’s finished. It’s in un’altra dimensione. Sono… Como se dice? ‘Midwife’? Sono midwife. I bring this film from this other dimension to here. But it’s finished there. But I bring it here. And this film may talk to me from everybody. From a prop, from an actor. I’m always listening.’

I can’t imagine that Pasolini was listening to anybody, except the voice in his head. In fact, he didn’t speak to me. He didn’t speak to me at all. That first morning in Claridge’s was the first and last words he ever said to me. He had his own agenda. He was creating an ambience that I was part of.

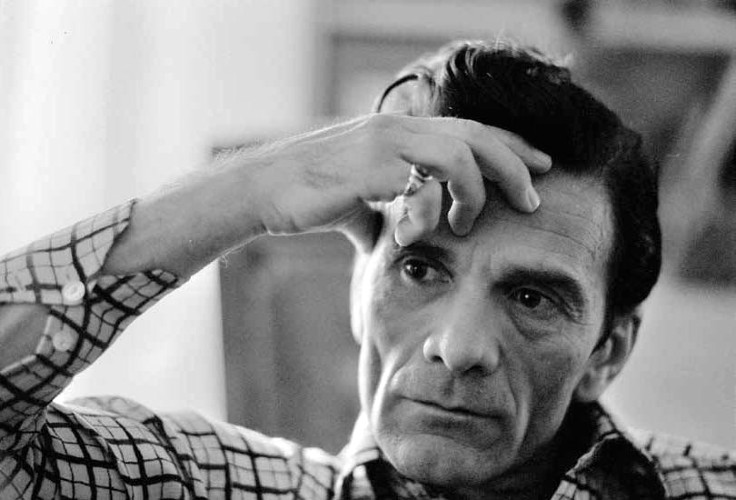

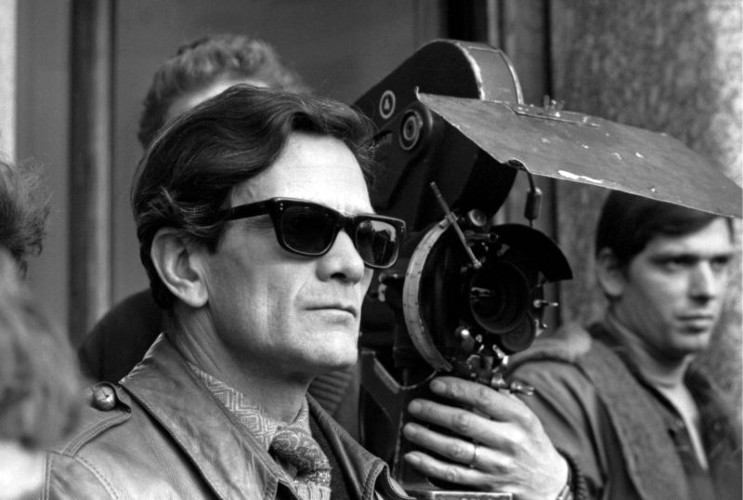

Pier Paolo Pasolini

My part in Teorema was virtually silent. I didn’t have any lines. The other characters would get their lines every day and he insisted they spoke them in English, which I didn’t really understand at the time. So there would be all these other actors who are learning their lines in English, and he wasn’t speaking to me at all. And then I realized that he had a kind of hidden camera which he operated. And I would notice him filming me when I wasn’t performing. So I began to think about what he was asking of me, really. And when I became friendly with Silvana I said to her, ‘You know him. He talks to you. He won’t talk to me. Find out about this part. Find out what he thinks about this part.’ And so she asked him, ‘What is the guest?’ And apparently he said, ‘He is a boy’. She said, ‘Yeah, he’s a boy, but what?’ And he said, ‘Well, he’s a boy with a divine nature’. So that was what I had to go on.

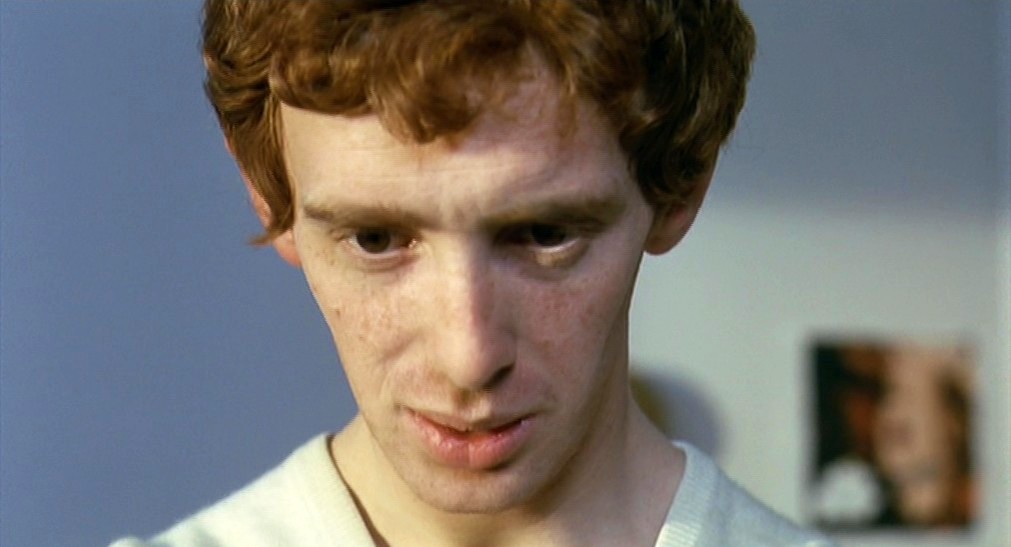

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

I thought to myself, ‘Okay, Pasolini’s a poet. He’s an Italian poet. Catholic. Gay. Lives with his mother. Communist. What is his idea? What would intrigue him about divinity?’ And I decided that what he would be most seduced by would be ‘Judge not’. And so I thought, ‘How can I reduce “judge not” to what he wants on camera?’ And so I figured that the whole of judgement, or judging, is pretty much covered by thought. So judging is thought-based and non-judgement really is non-thought. So from the kind of style of acting that I’d been doing with Fellini, I now came to a kind of a window of acting that was just being.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

So before I would go onto the set, I would just make sure that my head was empty. And in order for my head to be empty, I just had to be not only present, but I had to be aware that I was present. And so that’s what the character of the guest was, essentially. He was just somebody who was completely present. He had presence in the present. And he didn’t look at anybody with any kind of judgement whatsoever. So it didn’t make any difference to the guest whether it was a male, female, ugly, old, young, because the guest was just there, and he intuitively understood what they wanted.

Pietro and the Visitor, Teorema, Pasolini

I don’t think you could, by any stretch of the imagination, call Pasolini an optimist. I don’t think he was a fun guy. And I think that generally his criticisms were reserved for people other than himself. I’m not sure he was a guy who was self-critical. So, personally, I think all his philosophies are absolutely nowhere now.

[Terence Stamp develops his view of Pasolini the man more fully in his 2016 interview with Samuel Wigley for the British Film Institute. Here is the relevant extract: ‘Pasolini was closed down emotionally, small, unsociable, never communicated with me. I’m sure he had an enormous mind and I’m sure people thought the world of him, but I had no rapport with him at all. He never made any effort; as a matter of fact he was very offhand with me. We never had conversations, beyond the first meeting. But he did give me something invaluable by what he was and with his vision—which I had to work out for myself, it wasn’t anything he ever talked to me about.’]

Pier Paolo Pasolini

But if Pasolini were around now, he would probably think his philosophies were nowhere because he probably would have moved on. At the time, as part of the sixties, the whole sixties philosophy, what came out of the sixties—one of the things was a kind of ambivalence, but it would be more accurate to describe it as androgynous. The way in which it was understood at the time was that the next movement in humanity was that women–the word ‘man’, the first time the word ‘man’ was used, it meant ‘mind’. In other words, the word ‘man’ actually meant ‘mind’. So ‘hu-man’ was like ‘divine mind’. But it was considered a masculine attribute, was the mind. And it was always thought that woman—the primal attribute of a woman—was the heart. So, consequently, in the sixties, there was this whole trend for women to develop their intellect and for men to develop their heart or their emotions. And I think that in Teorema, that’s how I was thinking about it. I wasn’t.

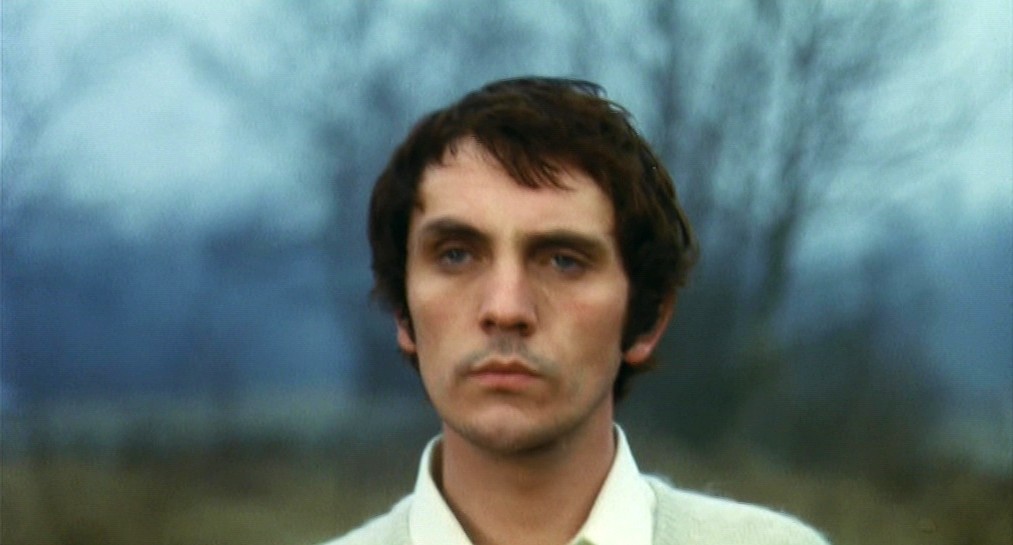

Pier Paolo Pasolini & Terence Stamp

Of course, the Guest was pansexual, because he didn’t identify with his individuality. He didn’t think of himself as his body. He just thought of himself as consciousness, that which was looking. And that which was looking, in the guest, was not different or separate from that which was looking in any of the members of the family. So he just felt at one with them. So he understood what kind of sex they dreamed of. And it didn’t make any difference to him because he was just energy. I went along with it at the time because I was beginning to understand that sex is the direction of energy. And when the film opened in London—to give you an insight on the English—when the guest is running through the woods with the dog, that got a huge laugh, because they thought I would shag the dog as well. That got the biggest laugh in the movie.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

Laura Betti was very intimidating because when Pasolini wanted to give me direction, he would tell her. And she, for some reason, was very coarse with me. And it was probably how he wanted her to be. I remember her coming to me before a take, whispering in my ear, ‘He wants you to keep your legs open. Just keep your legs open’. And then she would say, ‘He wants you to get an erection in the take. Can you get an erection? He wants you to have an erection.’ So I dreaded Laura Betti coming towards me because I knew I was going to get something crazy. And then she would say, ‘We’re going to have a love scene soon’. Oh, God! I have since met her and she was absolutely wonderful. A completely wonderful woman. So I think that probably she was like Pasolini’s creature. She was his conduit. If he had to talk to me, he would only talk through Laura Betti.

I knew the love scenes were going to make a lot of fuss. I remember when I had to seduce the son. I remember getting completely naked and getting into bed with his boy. But the truth was, I myself was viewing fear as a train of thought. So, in other words, any nervousness I might have had became a kind of reminder that I wasn’t in the moment. So I was able to just enter all these things absolutely clean. Teorema was the first time that it became a movement within consciousness for me as a performer. In other words, I had to make sure that I wasn’t there, there wasn’t any Terence there, while the camera was turning.

The Visitor and Pietro, Teorema, Pasolini

The Church’s attack on the film and the trial for obscenity was wonderful publicity. It was a very obscure movie—it was going to be seen by four drag queens and Einstein. When the Pope came out against it, everybody wanted to see it. So I personally couldn’t have been happier.

Pope Paul VI

Pasolini wrote the movie after it was finished. After it was finished, I understood why he had everybody speaking in English. Once he made the movie, then he just wrote what he wanted to say. And he just dubbed it. In other words, none of us ever knew what his ideas were at the time. So the first time I ever saw the film, I saw this completely new scenario which he’d obviously written after we’d finished shooting.

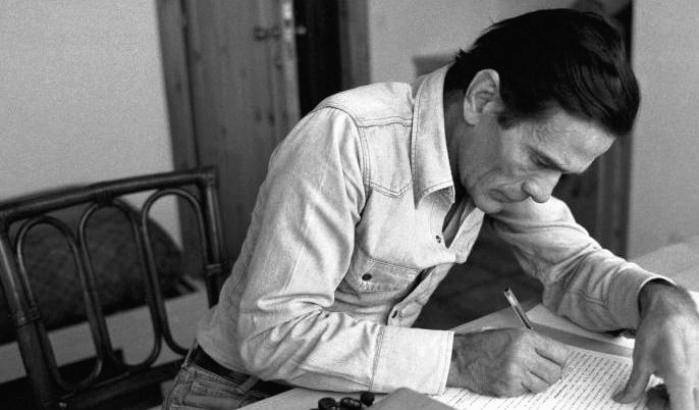

Pier Paolo Pasolini | Photo: Dino Pedriali, 1975

Another thing about Pasolini: They didn’t have any money to pay me, or very little. So I did the film for a percentage and the percentage was, let’s say, three points after 2.5 rollover. And during the movie, Franco Rossellini came to my agent and cried, and said they couldn’t finish the film with my clause. I was very young and very naive and I said, ‘Don’t worry about it. Give them an easier clause.’ The minute the film was finished, of course, they sold it to a Swiss company—which was themselves! So it was impossible to find out what happened to all the money. Pasolini may have been left-wing, a Communist in theory, but in reality he was looking after number one. They absolutely turned me over so I never received a penny—not a penny—from the film.

‘They turned me over. I never received a penny—not a penny— from the film.’

Illustration courtesy of coolclips.com

I travelled to India after my whole career collapsed in 1969. I couldn’t get arrested. And I just thought to myself—rather than wake up every day and face rejection, day-in and day-out, and no work—‘What else did I want to do before I became an actor?’ I must have had desires. Because my whole life was about becoming an actor. It was so difficult to become an actor for somebody like myself at that time. I thought, ‘I had always wanted to travel’. And I thought, ‘That’s what I’ll do. I won’t stay here and just have the phone not ringing’. So I bought a round-the-world ticket and I took off. And if I found somewhere I liked, I stayed there. Months became years and years passed, and I began to think, ‘Maybe it is all over. Maybe that was just a part of my life. Maybe I should get on with this.’

Terence Stamp in 1974 | Photo: Johnny Dewe-Matthews

I was actually in an ashram in 1977 and I was in orange robes and I was Swami Deva Veeten and I was learning about Tantric sex and a lot of other stuff. And when I’d first gone to live in the ashram, I had checked into a hotel called the Blue Diamond. It was an Indian hotel. After I’d been in the ashram for about a year there were some other English swamis. There was a guy called Curzon who’d become magically transformed into Davesh. There was another guy called Jeremy Lyon who’d been transformed into Swami Manishi. Us English lot would sometimes go to the Blue Diamond on Sunday morning. They have what’s laughably called a ‘full English breakfast’. Can you imagine what that was like? And this morning we went in and the concierge, who’d recognized me the very first time I’d checked in—because they’re all mad about cinema in India—he said , ‘Mr Terence, we’ve got a cable for you, Sir’.

Terence Stamp & Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, 1976

He pulled out the dog-eared cable that had obviously been there for a month, put it in my hand, and I remember thinking, ‘God, this is heavy’. Psychically, it was heavy. And I looked at the envelope and it said: ‘To Terence Stamp, the Rough Diamond Hotel, Pune’. And I thought this is a miracle. I opened it and it was from a long-suffering agent. When I first got to Pune, I must have written him a postcard saying, ‘Hey, I’m going to be here for a bit. This is where I am.’ And he obviously copied down the address wrong or tried to remember it. And it said, ‘Would you consider coming back to London to meet Richard Donner about Superman I and II with Marlon Brando’? He knew my weaknesses, my agent. ‘And could you possibly stop in Paris to talk to Peter Brook about Meetings with Remarkable Men?’ It was about eight years and this one telegram and suddenly I was going back through this big door.

Pataleshwar Cave Temple, Pune, India

So I went to the guru and I said, ‘My cup is full’. And I got a ticket and I stopped in Paris and I saw Brook. I was still wearing orange, with hair I hadn’t cut for about seven years. He was bemused, but I got the job. And then I went to London, saw Richard Donner and I got that job. And I said, ‘Listen, I need a month off to shoot in Afghanistan, before I do these Superman movies.’ He said, ‘That’s fine. We can give you a month’. And I wound up doing the two movies. They were both shot in Pinewood. So one day I’d go in and I’d be Prince Lubovedsky, who was Gurdjieff’s first guru, and the next day I’d go in and I’d be General Zod. So that was my comeback, really. That was 1978.

Terence Stamp as Prince Lubovedsky, Meetings with Remarkable Men, Peter Brook, 1979

There’s a lot more peace in my life than there was before. It’s not the ‘peace that passeth all understanding’. But there’s a lot less stress in my life. I just find there are long stretches where I’m completely okay with what’s happening.

Terence Stamp Interview, Teorema, BFI DVD bonus 2007

‘TEOREMA’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 10: Bettina

̶ And you, Sprague, what were you like at my age?

̶ I was like Terence Stamp in Teorema.

̶ I love that film!

It was at once strange and seductive, as if in taking off my panties I had unveiled reality.

̶̶ So you were the stranger, the saint, the guest? she asks.

̶ Yes.

̶ Did you make love with men?

̶ No. But if their desire, unbeknownst to them, was homosexual, I was the one who’d reveal it.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

̶ Did you make love with the mother, the maid, the daughter?

̶ Yes. But I myself didn’t know my secret. I was simply silent and available. The girl always gave the signal.

Mystery returned to the world: Naked, I assumed my desire and felt free to play with identity.

̶̶ Did you read Rimbaud in the garden, like Terence Stamp?

̶ I did.

̶ And did you always wear white?

̶ No. But I wore the equivalent: black.

̶ And did you become an actor in others’ erotic scenarios?

̶ Yes. I let them use me. I was simply there, passive until it was time to perform.

̶ Mysteriously present in their intimacy?

̶ Yes.

̶ And afterwards, after making love, were they transformed?

̶ They were. They couldn’t go on living as they’d lived before.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 12: Lucia

̶ My father had no love to give me. We never got along. What he really wanted was a son. Looking back, I see I became a tomboy just because I was trying to get closer to him.

Her kohl-rimmed eyes intensify her boundless trust in me. I’m not wearing white, but I feel like Terence Stamp in Teorema.

̶̶ Not once did he ever hug me. When I would put my arms around him, he would pull a face and tremble in horror.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 17

̶ You’re an idiot, Sprague, and you have to write your book as the idiot you are.

̶ Full of sound and fury, signifying nothing?

̶ No. More like your beloved Terence Stamp in Teorema.

̶ I see.

̶ It’s who you are, Sprague. You’re one of a kind.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 14: Izolda

Izolda’s a girl I met on the train, coming to Szczecin from Berlin. She’s a student at the university here, studying geosciences (coastal morphodynamics, the sedimentary continuum from river systems to continental margins). The sculptural lines of her face contrasted with the easy fall of her hair; her feminine earrings with the masculine cut of her clothes. We talked about Gombrowizc and Żuławski, Stanisław Lem and Grotowski, and all through the conversation we knew we’d end up in bed. It was thus without a word needing to be said that when I opened the taxi door, she got right in. (I wasn’t wearing white, but that’s how it happened.)

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 15: Iskra

The waiter took us for brother and sister, Iskra and I. Her hair’s as black as mine, her eyes as green. Guess that allowed him to overlook my southern complexion and her Slavic pallor, her youth and my youthfulness. She’s doing a PhD in plant science at Sofia University (mutant seedlings with aberrant circadian rhythms). Spent two years at Sheffield University. Speaks English with a Yorkshire accent! We met in the Botanic Garden. She was sitting on a bench, crying. I sat down beside her. Didn’t say anything, just reached out my hand. She took it. (I wasn’t wearing white, but that’s how it happened.) When we parted five days later, it was a strange goodbye.

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 4

Have you noticed Akiko’s been eyeing you? Is she struck by your beauty, intrigued by your demeanour, as you sit on the sofa beside me, legs flexed, stockinged feet on the footrest? I like her allure, her high cheekbones and free-flowing hair. I like the contrast of her loose cardigan and stretch-knit top, the subtlety of black on black. I like her black ankle boots, her black skinny jeans, her black eyes and black hair. But I’m not in a black mood. In fact, I’m feeling as luminously white as Terence Stamp in Teorema. Is that why innocence and honesty, in the conversation that followed, dispensed with the armour of irony?

Terence Stamp, Teorema, Pasolini

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

‘TEOREMA’, OR THE RESTORATION OF DESIRE

By Richard Jonathan

The environs of Milan, a wealthy family in a mansion: Paolo and Lucia, husband and wife; Odetta and Pietro, the children (respectively in their late- and mid-teens); Emilia, the mute, middle-aged maid. Into their household comes ‘the Visitor’, a beautiful young man. Like a moth to the flame, each member of the family is attracted to the mysterious guest; enigmatic, their desire wells up and seeks him to satisfy it.

Terence Stamp (the Visitor), Teorema, Pasolini

First, Emilia. Observing the visitor reading in the garden, she feels her attraction to him and is overcome by a feeling of transgression. (How do we know this? In Teorema, the silence of the images is as eloquent as the actors’ body language.) She runs inside, stands before a mirror surrounded by pictures of the saints, and—in a moment of pure cinema typical of Teorema—takes off her earrings, the emblems of her desire.

Laura Betti (Emilia, the maid), Teorema, Pasolini

Back outside, raking up the leaves, she is again overcome by the visitor’s presence; as she stares at him, tears flow from her eyes. She runs into the kitchen and begins to gas herself at the stove. The Visitor rushes to her rescue, gets her to her bedroom, and—at her invitation—makes love to her.

Laura Betti (Emilia, the maid), Teorema, Pasolini

Next, the son. Unable to restrain his desire, he draws back the bedsheets as the Visitor sleeps, waking him. Acutely embarrassed, he apologizes. The Visitor joins him in his bed.

Terence Stamp (the Visitor), Teorema, Pasolini

Next, the wife/mother. Disrobed, she lies back and awaits the Visitor. Returning from a walk in the forest, he is touched by her embarrassment before him. With the same tenderness he’d shown the maid and the son, he makes love to her.

Silvana Mangano (Lucia, the wife and mother), Teorema, Pasolini

Next, the daughter. Relaxing in the garden, she runs inside and returns with a camera to photograph the Visitor. She then takes him by the hand, leads him inside to her bedroom, and shows him her photo album. In their bubble of intimacy she bares her breasts to him. We imagine the rest.

Anne Wiazemsky (Odetta, the daughter), Teorema, Pasolini

Finally, the husband/father. Bed-stricken by his troubling desire, he recovers after some care by the Visitor. They drive out into the country. The husband mentions his moral concerns, and the confusion he feels. Stopping for a drink, they box playfully. Further out in the country, the Visitor lies down in the winter vegetation by a body of water. The husband approaches. We imagine the rest.

Massimo Girotti (Paolo, the husband and father), Teorema, Pasolini

The angel-postman who’d announced the Visitor’s arrival returns with a letter announcing it’s time for the Visitor to depart. Husband, wife, daughter, son, maid: Each testifies to the Visitor (the maid by lavishing kisses on his hands) that he has made a radical break in their life, making it impossible for them to be as they were before.

Laura Betti (Emilia, the maid), Teorema, Pasolini

The Visitor leaves. Emilia becomes a mystic, touched by miracles, and is buried alive at her own request.

Laura Betti (Emilia, the maid), Teorema, Pasolini

Odetta becomes catatonic, the caress she’d given the Visitor sealed in her fist as she lies rigid on her bed.

Anne Wiazemsky (Odetta, the daughter), Teorema, Pasolini

Pietro becomes an artist, and discovers the truth of that condition.

Andrés José Cruz Soublette (Pietro, the son), Teorema, Pasolini

Lucia cruises the streets of Milan in search of young men; as they make love to her, she only misses the Visitor more.

Silvana Mangano (Lucia, the wife and mother), Teorema, Pasolini

Paolo, having given his factory to the workers, roams naked upon volcanic slopes, wind-borne ash muting his cry.

Massimo Girotti (Paolo, the husband and father), Teorema, Pasolini

Free of morality, beyond good and evil, the Visitor restores desire. Neither fool nor saint, he is the stranger who allows our self to be less false (Winnicott), our efforts to end in a better failure (Beckett). But when he leaves we’re on our own: Individualized. Alone.

Terence Stamp (the Visitor), Teorema, Pasolini

This is the theorem of Teorema. As demonstrated by Pasolini, it makes for a brilliant film, a purely cinematic parable. And a fine companion piece to that other Pasolini masterpiece, The Gospel According to Saint Matthew.

Terence Stamp, The Visitor, Teorema | Enrique Irazoqui, Jesus, The Gospel According to St. Matthew

‘TEOREMA’, OR THE ALLEGORY OF REPRESSION

THOMAS PETERSON ON ‘TEOREMA’

From Thomas E. Peterson, ‘The Allegory of Repression from Teorema to Salô’ (Italica, Volume 73 Number 2, 1996). The full article is available on JSTOR.

Who is the Guest? He is neither God nor the devil. He is not a priapic principle and he is not Pasolini. Nor is he the ‘theorem’. Instead he is a daimonic messenger, a figure of the sacred and metaphysical who is exactly as mutable as the psyches of those he encounters. In his presence the Guest reveals social and sexual repressions which, after his departure, further reveal the arch-repression of bourgeois society: the repression of the sacred.

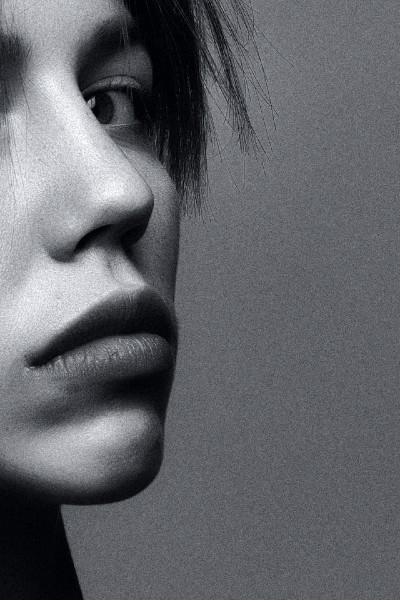

Photo: Alexander Krivitskiy

If the film’s goal is to present a series of case studies of persons provoked by sex or love into a form of self-knowledge, the conclusions are various, with an obvious symmetry between the father, who has lost his self, and Emilia, who is sanctified. That Emilia is typical of her class is evident when another maid named Emilia replaces her in the house. She meanwhile has begun a Christ-like transformation, returning to her peasant home to undertake a period of ascesis and purification, eating nettles, conducting miracles, levitating over the farm buildings, then walking to a construction site where she asks to be buried, not to die: ‘I came to cry, not to die,’ she states as her tears form a miraculous fountain.

Photo: Septumia Jacobson

Andrea Zanzotto has written of Teorema, ‘In this work there is a perfect balance between expressive factors and referential elements that are put together in a theorem destined to remain up in the air, as regards a possible demonstration, but open on infinite corollaries’. This idea of open-endedness is typical of metaphorical thinking, and to the use of enthymemes and abductions one finds in allegory; the proof is not in the attainment of certainty, but in the realization that the ‘parable’ in question is, in Zanzotto’s words, ‘religious, metaphysical, but also, and perhaps more strongly, historical-existential’. The whole emphasis of the work is to suggest, not confirm. The Guest will not return, but the sacred and daimonic presence may, to guide the remaining family members to their resolution.

Photo: Deleece Cook

JACQUES LACAN ON THE SACRED AND DESIRE

From Emmanuel Koerner, ‘Du divin, du sacré et de la religion selon Lacan’ (Paris: Essaim 2016/2 n° 37, pp. 19-34). This extract translated by Richard Jonathan. The article, in French, is available in full on CAIRN.

The zone traversed by the Sophoclean heroes, where life and death interpenetrate (we recognize here the chief characteristic of desire), is the limit of the second death*, where man does not disappear from this accidental death-event that that each of us wants to avoid by ‘always postponing the question of being’ (Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis), but where, like Oedipus and then his daughter Antigone, he advances in the mè phunai, the ‘rather not be’, of he who, have fulfilled his destiny, having been to the very end of his desire, of his division, of his Spaltung (splitting), ‘erases his being’, ‘wilfully removes himself from the order of the world’. He ‘aspires to annihilate himself in order to insert himself into the parameters of being’, ‘to destroy himself by the very act of “eternalizing” himself’ (Lacan, Le tranfert), within this ‘internal limit of desire’ that places us beyond life. This, it would seem, is the place where Lacan situates the sacred, that ambivalent field where desire displaces the ethical question of the good, beyond all social demands.

*The gods, revelation in reality, are the outburst of signifiers requiring an essence that they conceal. But their reach has disappeared (‘the Great God Pan is dead’), and has been replaced by the image of the crucifixion, incarnating the death of God, truth of the Name-of-the-Father. It is therefore behind this image that the hidden essence is to be found, the space between-two-deaths revealed in the Greek tragedies, space of the sacred, of indestructible desire, at the cost of a pound of flesh. The second death that presides over this space is depicted in the Christian image and interpreted in a Christian way ex-nihilo, a signifying creation from which emerges the Thing and the death drive. [This note is taken from the English abstract published with the French article.]

Gustave Moreau, Oedipus and the Sphinx, 1864

This field of the sacred, field of desire, is figured in the holy ground of the Furies where Oedipus disappears, the realm of the immortal where man assumes his mortality, just as, in Antigone’s unwritten laws, one finds the laws of desire (Lacan, The Ethics of Psychoanalysis).

Odilon Redon, Oedipus, early 20th c.

Here the regime of goods represented by the civic order, which founds traditional hedonistic ethics, is surpassed: It’s Oedipus who gouged out his eyes after having measured the illusion of his past happiness (honours, marriage, power), Antigone who holds Creon in check and, in her suffering, looks from the perspective of death at the life she is renouncing. Desire is paid for with a renunciation of happiness, it is paid for with the loss of a good: jouissance, the ‘pound of flesh’.

Michael Mayhew, The Oedipus Plays, 1996