THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE | LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN

Jean Eustache, 1973

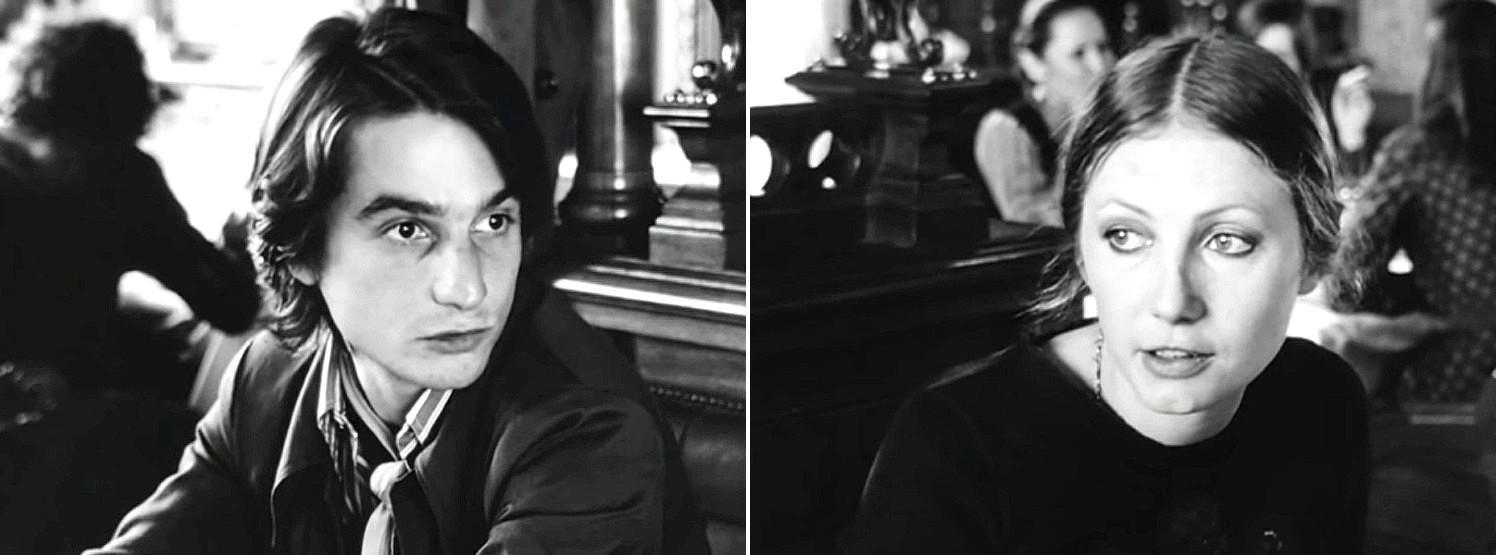

Françoise Lebrun (Veronika) | Bernadette Lafont (Marie) | Jean-Pierre Léaud (Alexandre)

Natacha Thiéry on ‘The Mother and the Whore’ (Jean Eustache)

ECLIPSES OF THE LOVER’S BODY

Natacha Thiéry

From Natacha Thiéry, ‘Éclipses du corps amoureux: Sur quelques films de Jean Eustache’ (Nouvelle revue d’esthétique 2012/2 n° 10) pages 39-49. This excerpt translated by Richard Jonathan.

Bernadette Lafont & Françoise Lebrun, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

The Mother and the Whore opens with the desperate attempt by Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud) to get back together with his ex, Gilberte (Isabelle Weingarten), who is probably going to marry another man. He lives with Marie (Bernadette Lafont) in her apartment and hooks up with Veronika (Françoise Lebrun), a woman open to love (and sex) who fascinates him but to whom he makes no real commitment. And here arises the paradox of desire, that movement towards the ever-present lack within that nothing can overcome, that animating tension without an object: whatever it is seeking forever escapes capture.

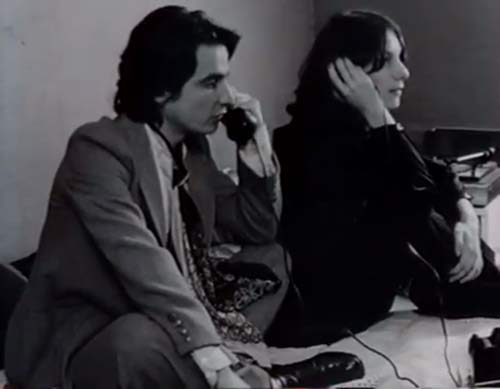

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Isabelle Weingarten, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

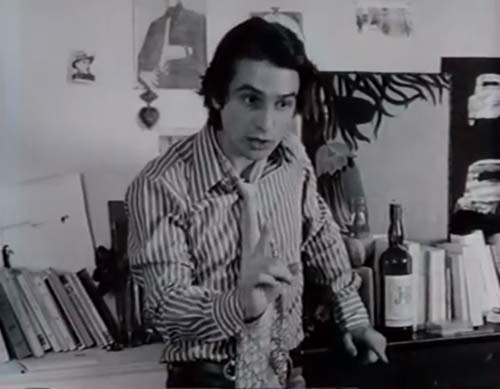

Alexandre’s relation to speech is obsessive, and shows that if desire is indeed in words, words cannot circumscribe it. His feverish speech denotes the indecisiveness of someone who cannot choose the object of his desire (in order, no doubt, to avoid the risk of losing it) and only affirms, in the play of discourse, non-choice or the incapacity to mourn that making a choice would demand. The film highlights the distress of the three main characters and their difficulty in reconciling ‘freedom’ and feelings. At any rate, it is indeed speech, as an end in itself and as a veritable object of desire, that imposes itself on both ear and eye.

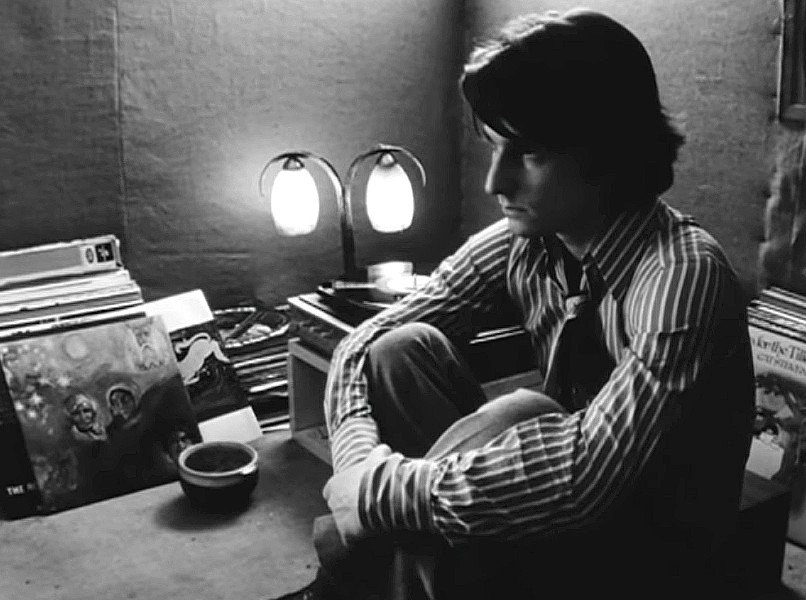

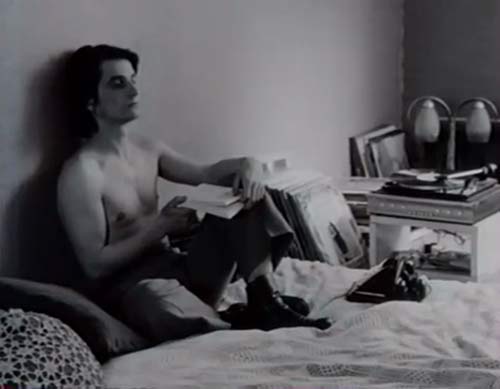

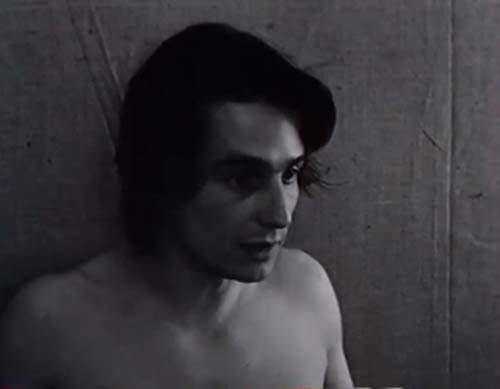

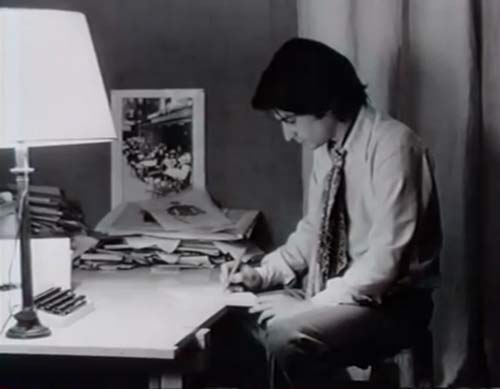

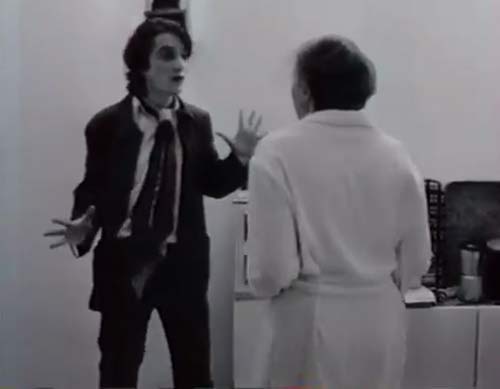

Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

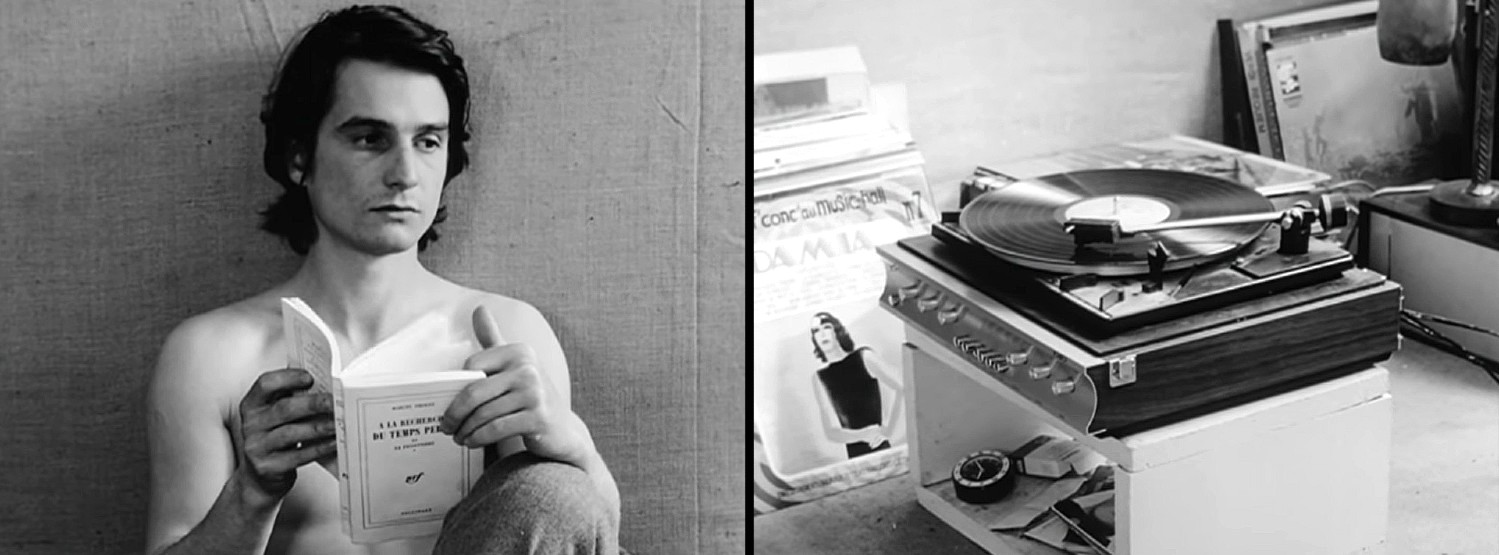

In its urgency, however, the masculine speech (especially in the monologues) defers physical contact, since it separates more than it unites. All the more so because it merges with all action: it is action as such and thus, being performative speech, reduces action to enunciation. It consequently fails to express the essential: the feeling of love. That is why it is popular music—from times past (Damia, Fréhel, Piaf) or contemporary (Deep Purple, The Rolling Stones)—that fills this gap…

Proust, A la recherche du temps perdu | Damia, Un Souvenir

… in shy tenderness with Veronika…

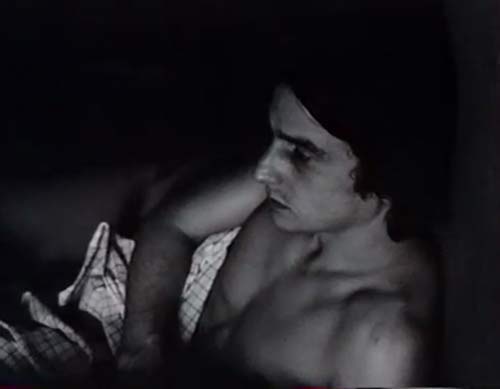

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

… in the grandiloquent attempt at reconciliation with Marie.

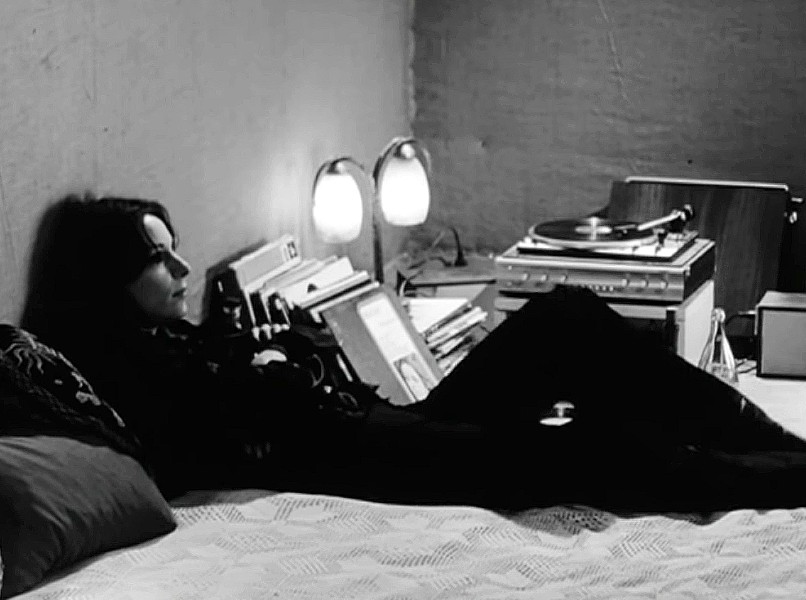

Jean-Pierre Léaud, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

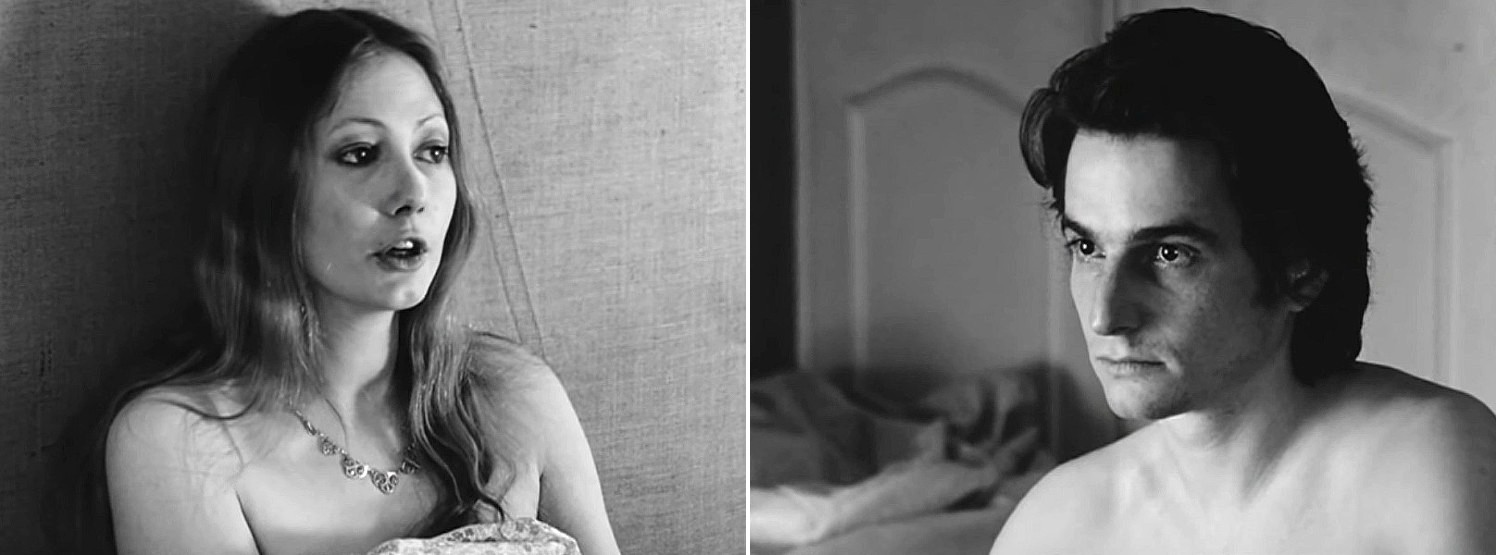

That is also why it is only the women who articulate desire in terms of a lover’s discourse and, especially at the end, seize the initiative and dominate the conversation. In doing so, they share the preciosity of addressing each other in an erotic formal ‘vous’ while at the same time appropriating the vulgarity of taboo language.

Françoise Lebrun & Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

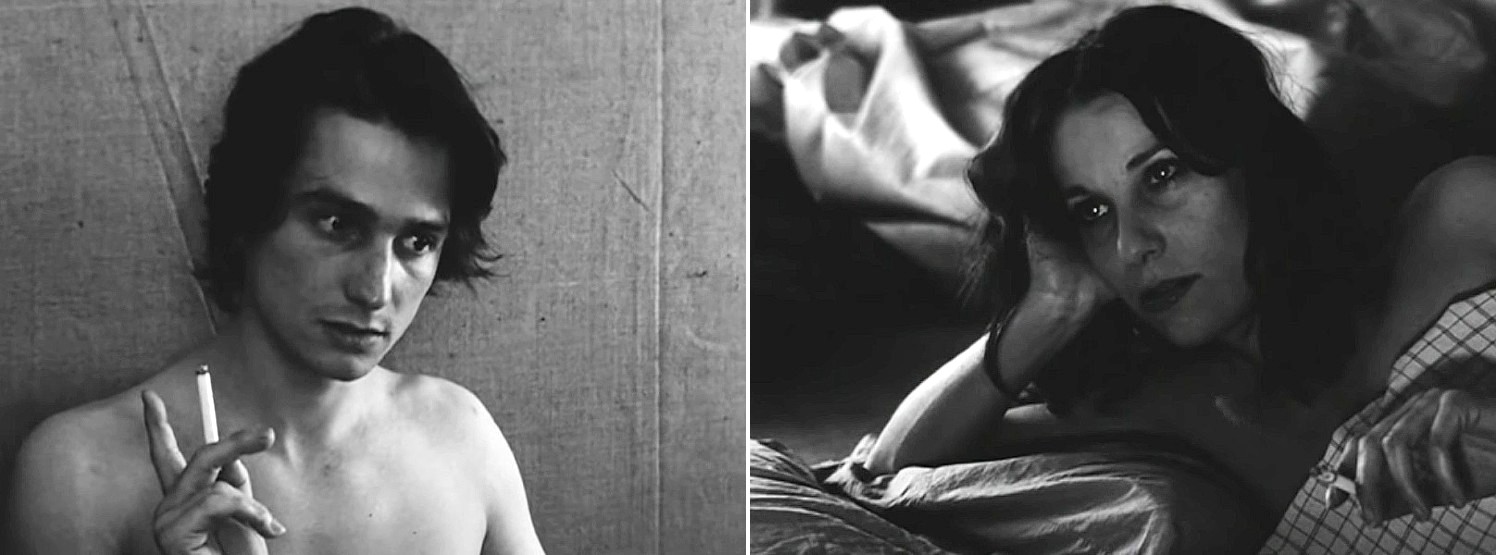

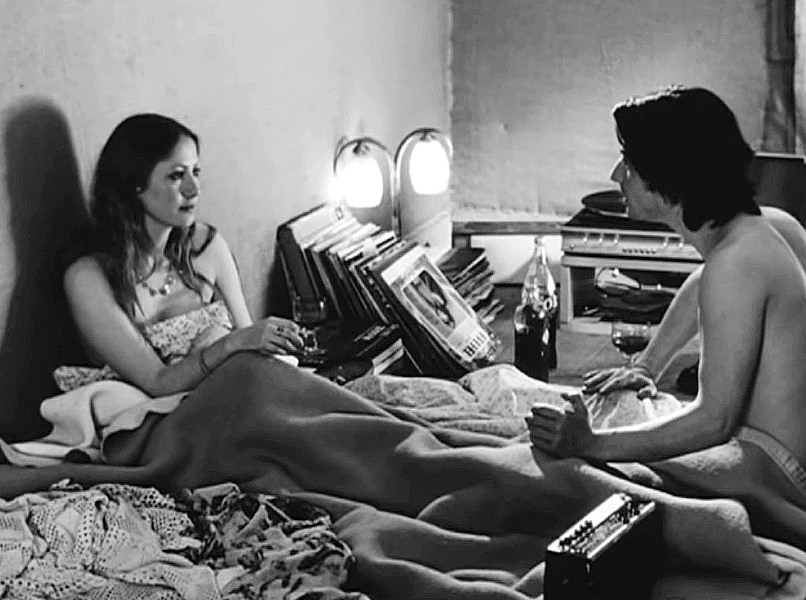

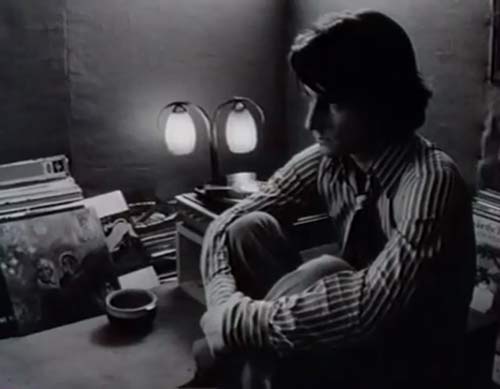

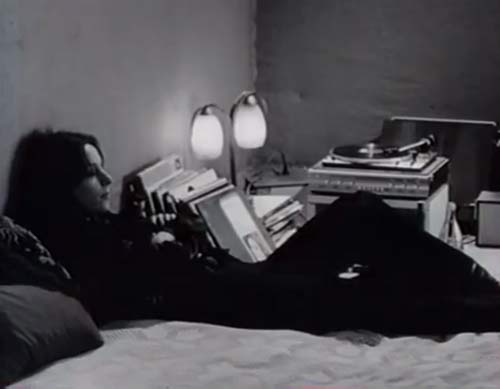

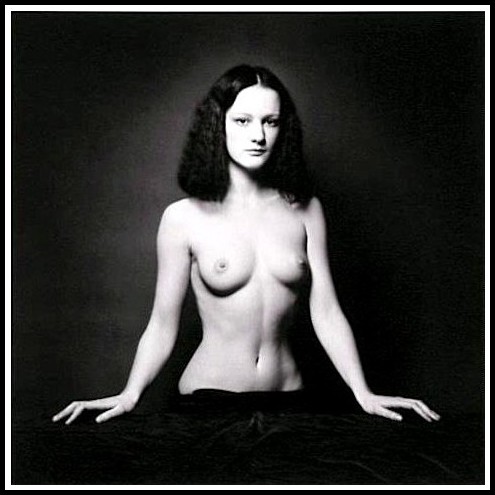

In this regard, the naturalness of Bernadette Lafont (oscillating between an ironic calm and outbursts of anger) is striking, and contrasts with the litany-like, almost masochistic repetition by Françoise Lebrun of terms like ‘fuck’ and ‘a maximum’ [‘wiggling her ass a maximum’, ‘a maximum of play-acting’]. This paradoxical mix, at the heart of language, of a form of preciosity and outright vulgarity highlights the place of the body in the love triangle. The décor of most scenes in Marie’s apartment is a big mattress on the floor. The characters use it at all hours of the day and night, more often to talk than to make love. Indeed, the singularity of speech leads to the effacement of bodies, bodies which remains hidden and strangely static. Veronika’s body, most of the time, is just a dark silhouette underneath a long black shawl and flowing clothes, while her hair is gathered in a bun and her gait is slow and earth-bound.

Bernadette Lafont & Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

Paradoxically, in this film that amply addresses the question of physical relations, the body remains largely outside the picture frame. Eustache is a filmmaker with a keen sense of modesty whose pleasure, tinged with a genial perversity, consists in associating this reserve (and, as the case may be, the frustration of the gaze) with an outpouring of verbal vulgarity.

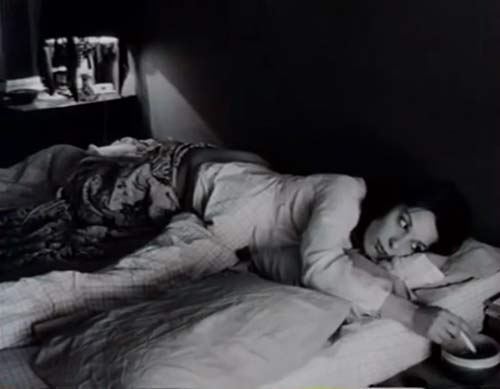

Françoise Lebrun, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

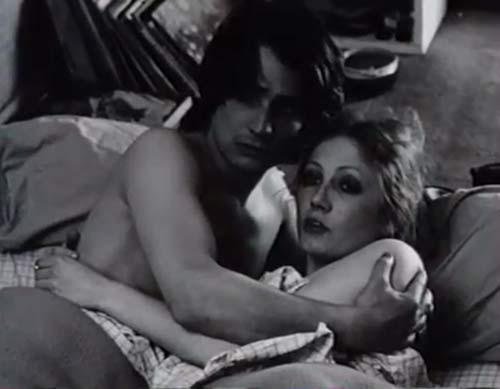

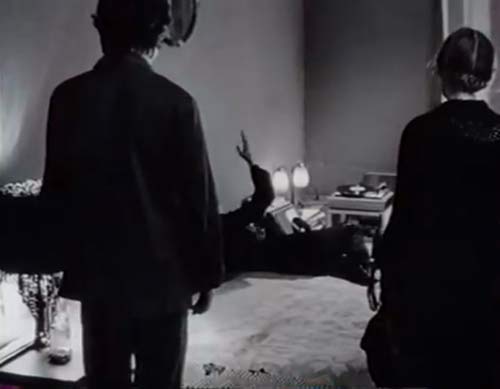

An exception to this effacement of the body is the scene where Veronika, drunk, telephones Marie and Alexandre in the middle of the night (they’d been sleeping) and comes over to their place. In the general economy of the film, this scene fleetingly gives an exceptional presence to the body, a presence that goes hand in hand with an increasing scarcity of (masculine) speech. Indeed, as the film advances, the feminine voice comes to predominate.

Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

Veronika knocks on the door. Marie gets up to open it. Filmed in wide shot, we catch a glimpse of Bernadette Lafont’s sovereign nudity before she slips on her nightgown and, once Veronika is inside, slips it off again. Veronika then rhetorically asks: ‘Am I interrupting something? Maybe you were fucking?’. She then adds: ‘Pay no attention to what I say, I’ve knocked back a maximum tonight’. Then, taking off her clothes, she asks: ‘Can I join you in the sack?’.

Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

The shots that follow, mid-shots of head-and-shoulders, concentrate on the face. The relatively high-key cinematography brings out the luminosity and relief of naked skin.

Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

In a few beautiful close-ups, all in silence, Veronika kisses Alexandre then turns toward Marie and kisses her.

Françoise Lebrun, Jean-Pierre Léaud & Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

Alexandre watches them, then takes both in his arms.

Jean-Pierre Léaud, Bernadette Lafont & Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

Veronika draws aside and watches Alexandre and Marie intently. Her words, however, then come to interrupt the movement of bodies, occasioning an embarrassment that had been absent until then: ‘You know what I’d like? That the two of you fuck. People who fuck because they love each other, that’s the most beautiful thing in the world’. She says this with gravity, a gravity tinged with sadness that foreshadows her long, final monologue. More than her gaze, here it is Veronika’s words that impinge on the intimacy of bodies and highlight the difficulty, running throughout the film, of getting together, of forming a couple—a unit as much despised as desired. Nevertheless this scene, in which the materiality, the sensuality, and the presence of bodies is fleetingly effective, forms—despite the crudity of the dialogue—one of the most delicate, reserved, and poignant passages of the film.

Jean-Pierre Léaud, Bernadette Lafont & Françoise Lebrun, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

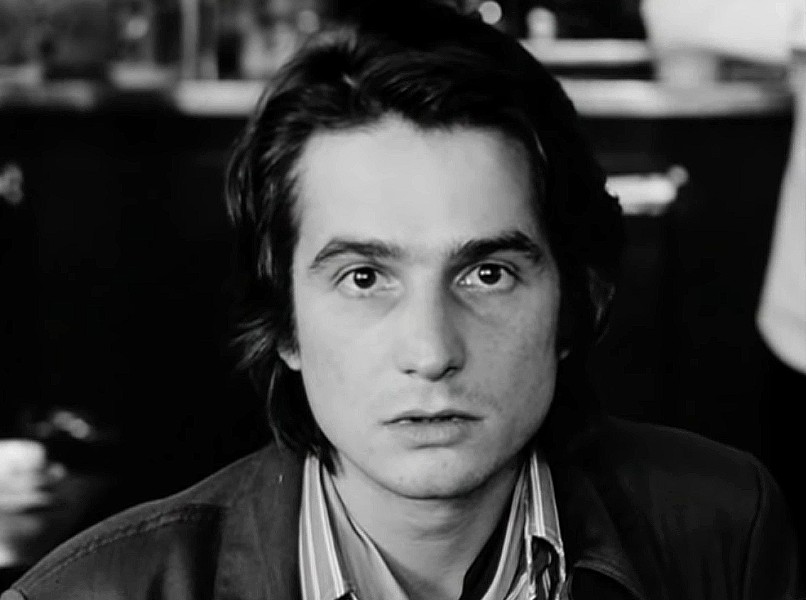

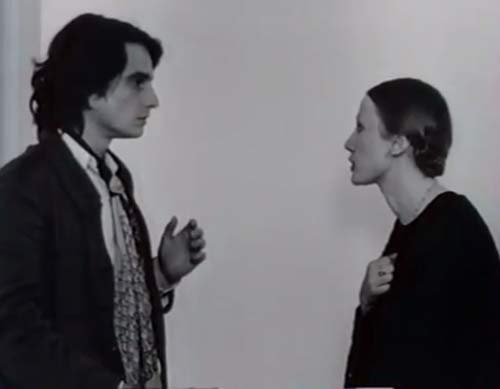

Overall, then, together with the voices, it is the faces that predominate. The facial expressions, but also the words, betray their status as substitutes for the trials and tribulations, the prevarications, of the body. Pierre Lhomme, the film’s cinematographer, worked out with Eustache a look that combines a homage to cinema—including silent cinema, particularly that of Murnau and Dreyer—and a Bressonian aesthetic of sobriety and reserve, one that excludes technical effects. In contrast to this is Alexandre’s logorrhea, which evokes the narcissistic loquaciousness of a Sacha Guitry, another filmmaker Eustache admired.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Bernadette Lafont, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

The grain of the image, quite noticeable, renders visible the intensity of the atmosphere; the image acquires a roughness and density that give it a tactile quality. This quality is also evident in the grain of the voices and the texture of skin. In a black-and-white that contributes to the ‘dignity of the image’, Pierre Lhomme was able, in a succession of often static shot-reverse-shots, to capture the play of vibrations and nuances. He filmed, as he has said, ‘listening as much as speaking’, and he did so with the acuity demanded by this feverish film. Under his sensitive gaze, the naked faces, more than the bodies, radiate their presence.

Bernadette Lafont & Françoise Lebrun, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

As for the voices, Alexandre’s reveals his feigned detachment and the dandyism of his sophisticated sentences and pontificating statements, while Marie’s and Veronika’s reveal their distress, sorrow, and physical desire. Just like the face, the voice bears the body; in this sense, the body, in the film, can be said to wander. The Mother and the Whore, as André Habib notes, ‘is literally composed with voices, just like chamber music.’* In this sensitive and sensual materiality, it is the lover’s body, including its musical dimension, that the voices conjure.

* André Habib, ‘Voix’, in A. de Baecque (dir.), Le Dictionnaire Eustache (Paris : Éditions Léo Scheer, 2011) p. 304

Françoise Lebrun & Bernadette Lafont, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

A number of critics have seen a similarity between Alexandre and the subject of Roland Barthes’ Fragments of a Lover’s Discourse, with one even going so far as to suggest that Barthes’ book, which appeared four years after the film’s release, might be considered the first essay on La Maman et la Putain. If intertextuality does indeed come into play between the two works, making a parallel between them is not necessarily justified. Granted, they share a largely similar impetus: a man, his lover having left him, tries to keep what had already been lost and redirects his suffering via a creative process (of writing, initially, as was the case for Eustache) where speech occupies a nodal point. (Jean Eustache explained that it was his break-up with Françoise Lebrun that triggered the film; he wrote it for her and Jean-Pierre Léaud.) In both Eustache’s film and Barthes’ book, the subject of discourse is less engaged in a relation to another person (except a fantasized one, as it inevitably is in a love relationship) than he is speaking from a place of solitude and retreat, the love object remaining fundamentally absent.

Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

In the book as in the film, what is exposed is the paranoid-obsessive monologue, now playful, now elegiac, of the prolix lover (a pleonasm) trying to fill a void and, when that doesn’t work, encountering the other only via a side effect derived from frustration. Note, in this regard, the resistance of the love object in her absence (Gilberte) or in her own suffering and attempts to neutralize discourse’s games and masks (Veronika, Marie). Many constitutive elements of the film—certain traits of the characters, the dialogues, the postures of the body—can be considered possible, and perhaps contradictory, avatars of Barthes’ fragments.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Bernadette Lafont, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

But is Eustache’s masculine protagonist really a subject in love? It is clear that if he is, it is first and foremost at the beginning of the film, in his relationship with Gilberte (his ex, the lost love), who remains immured in her refusal and her flight. It is in this prologue to the film—the only time when Alexandre is as lucid as he is passionate, notwithstanding his irremediable separation from Gilberte—that he adopts a lover’s discourse, one that Marie and Veronika will later appropriate.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Isabelle Weingarten, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

It is when bodies can neither touch each other nor move each other that the subject adopts such an attitude. And, by dint of speaking, the character, impelled by an ‘auto-erotic’ monologue, keeps at a distance and even excludes the woman (and her body) who loves him. In this regard, a comment by Pierre Lhomme is significant. Referring to the repeated use of the shot-reverse-shot, he said that it was ‘the very subject of the film, namely, can the man and the woman co-exist in the same image?’. And indeed, the shots that raise this possibility are few and far between, as if Alexandre suffers from an incapacity to inhabit his body, to fully incarnate it, and to expose himself to the feeling of love. Paradoxically, his immaturity pushes him towards bodies as towards a rampart against feelings that have become more taboo than sexuality.

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

Now, to return to Barthes, if in the film as in the essay everything is mediated by words and discourse, it is, in contrast, in their relation to words and discourse that Barthes and Eustache differ. While the Barthesian narrator finds a certain redemption through the voluptuousness of the words he wields and the pleasure they procure, the very words that enable him to (re)gain a grip on himself, the Eustachian character, bogged down in a verbal drama, fails to find any form of redemption. While Alexandre, incapable of overcoming an interior wound that is finally more existential than related to love, laments a loss that he exhausts himself in trying to redeem, Barthes’ narrator responds by making pleasure an imperative, or rather an imperious riposte to the anti-pleasure brigade. In this effort, the writer gains new theoretical energy, his feelings relieved (and un-repressed), while the filmmaker goes deeper into renunciation and, already, digs his tomb. But beyond this, it is mainly in their respective relationships to transgression that the two authors distinguish themselves from each other.

Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

For Eustache transgression, in the end, is only apparent (not real), and, at least for the male sex, comes up against a persistent taboo. What is most intimate escapes all regard, but the intimacy in question is not that of the sexual body with its organs and orifices but rather that of the feeling of love. If the lover’s body is so rarely present, or present with such difficulty, it is because to show it would entail showing the feeling of love. The crudity of the language is thus inversely proportional to the capacity to speak or to show the lover’s body and to reconcile eroticism and sexuality. We can thus appreciate the audacity of Barthes’ Fragments and their explicit transgression, for what they sketch is indeed this integration of eroticism and sexuality in the love relation. And against the exaltation of the writer, against his ‘morality of affirmation’ that declares ‘you have to affirm, you have to dare, to dare to love’* stands the disquiet of the filmmaker for whom (certain) feelings remain taboo.

* Roland Barthes, Le Grain de la voix, interview with Philippe Roger in Playboy (1977), Paris, Le Seuil, 1981, p. 322

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

When all is said and done, in The Mother and the Whore the monomaniacal urgency of a discourse where words are largely an end in themselves and the real object of desire keeps lovers’ bodies apart. Nevertheless, this discourse silently allows, as an undercurrent, the circulation of desire between filmmaker, film and spectator.

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

Eustache recognized that at the origin of his work lay an inner turmoil, nervous and physical, that was ripe for aesthetic transformation in and through cinema: ‘If you make a film, it is because you have been moved emotionally’.* His intransigence and his obsession were aimed at doing justice to (and giving an account of) this vibration, this displacement onto an aesthetic plane. As a result, the real lover’s body is, on one hand, the implicitly present body of the filmmaker as cinéphile (in the strongest sense of a necessary relation to cinema), and on the other hand, the body of the spectator, in his intimate conversation with the film.

* Jean Eustache, interview with Sylvie Blum and Jérôme Prieur (1983), republished in Alain Philippon, Jean Eustache, Éditions des Cahiers du cinéma, coll. « Auteurs », 2005 (1986), p. 124.]

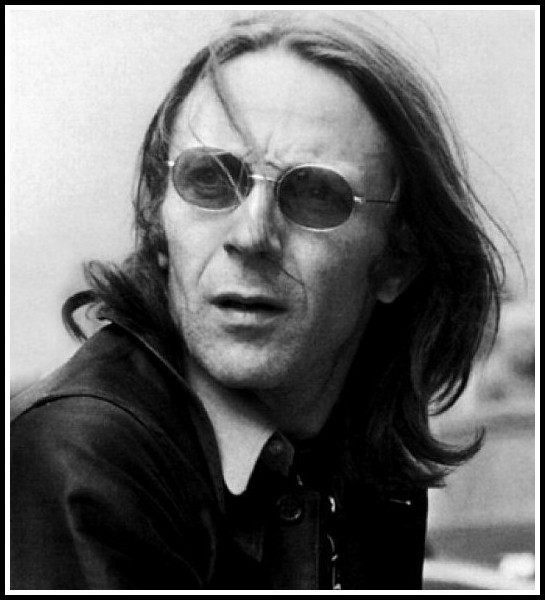

Jean Eustache

La Maman et la Putain | The Mother and the Whore

A COUPLE IS A CONSPIRACY IN SEARCH OF A CRIME

Richard Jonathan

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Bernadette Lafont, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

ALEXANDRE: I’m just a poor, average guy. A poor, average girl wants to see me. Well, I’m happy about that and whatever happens, I won’t give it up. And you know I’m not talking about sex.

MARIE: But that’s what’s coming.

ALEXANDRE: What does it matter? Dipping your quill in one ink well or another?

MARIE: Yes, but that hurts so bad.

ALEXANDRE: I know.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

Paris, Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Early 1970s. The ‘sexual revolution’ has taken place, but the heart remains a lonely hunter: Not the material of tragedy, yet from this material Jean Eustache has made a film that, while in no way tragic, attains the surpassing dignity of that form.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

Veronika, the ‘poor, average girl’ that Alexandre mentions, may be poor (she is a nurse), but she is anything but average. Disrupting the couple constituted by Alexandre and Marie, she drives the film into the heart’s sombre depths, and with incandescent lucidity illuminates them.

Bernadette Lafont, Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

Beyond its time and place, beyond the banality of the love triangle, what emerges from The Mother and the Whore is a vision of three people trying, like Leonard Cohen’s ‘drunk in a midnight choir’, to be free. That they do so through an excruciating intimacy filled with love, sex and alcohol, gives the film its distinctive substance.

Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

As for the form, suffice it to say that the fade-in/fade-out punctuation of time, each sequence a duration of lived experience, combines with the purity of black and white and the play of silence and sound to confer on the film its classical dignity.

Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

But what does the film tell us of its themes—love and freedom, desire and self-deception? It tells us nothing. But it shows us everything.

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

‘God may be dead, but the faithful couple won’t lie down.’ Alexandre, in his relationship with Veronika, tries to realize an ideal of ‘free love’. Marie gives him her blessing. And yet, when the three of them are in bed together and Alexandre starts making love with Veronika, Marie is driven to swallow a bottle of sleeping pills. Why? The worm of love in the apple of sex? The premonition of a shared future on the verge of foreclosure? The fear of finding herself in a chain of debt-counter-debt, with her emotions as tokens?

Bernadette Lafont, Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

‘A couple is a conspiracy in search of a crime. Sex is often the closest they can get.’ Alexandre and Marie, it seems, never found their crime. Veronika, for her part, could never settle into a couple. Alexandre, torn between Veronika, Marie and Gilberte (his ex), has lost the plot of his conspiracy. Crime, couple, conspiracy—all kaput. What’s left? Why, sex, of course! Simple, isn’t it? And yet so complicated.

The quotations are from Adam Phillips, Monogamy (London: Faber, 1996) p. 10 and p.21.

For another version of the ‘the couple is a conspiracy…’ theme, see Roman Polanski, CUL-DE-SAC.

Françoise Lebrun, Jean-Pierre Léaud, Bernadette Lafont, Isabelle Weingarten

‘THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Four Chapter 8

Down Roncesvalles they ride, past the Repertory Cinema. Jean Eustache, The Mother and the Whore.

̶ That’s a brilliant, brilliant movie. Would you like to go and see it with me? he asks her.

̶ Okay, but it had better be soon. My boyfriend’s getting out of jail any day now.

̶ We can go tomorrow. Do you have a babysitter for Eric?

̶ No.

̶ I’ll get my flatmate to look after him. He’s a medical student.

̶ Ah, that could be useful.

He wonders what she means.

̶ Where do you get off? he asks her.

̶ Two stops. Marion Street. Would you like to come up for some tea?

̶ Okay, thank you.

Françoise Lebrun & Jean-Pierre Léaud, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

That evening they go to the Repertory Cinema to see The Mother and the Whore. Sitting beside him she smells milky, like a baby. He feels great tenderness towards her, but dares not touch her. He thinks of the guys in the line-up, all eyeing her. It must be hard to deal with, he thinks, the constant pull of sex that beautiful women elicit.

̶ Normally I only go to horror movies, she says. And any film with Marlon Brando! This will be only my second French movie.

̶ What was the first?

̶ Last Tango in Paris.

̶ I love that film!

̶ Yes, it’s fantastic, isn’t it?

̶ It’s my favourite film of all time! After the one we’re about to see, that is.

Her eyes catch the light in his.

Françoise Lebrun, The Mother and the Whore, Jean Eustache

̶ And you know what? The guy who play’s Jeanne’s boyfriend in Tango plays the lead in this film.

̶ Oh really?

̶ Uh-hm.

̶ Have you been there, to Paris?

̶ Yes.

̶ I’d love to go. Do you speak French?

̶ I do.

̶ Maybe you could teach me. I only speak German.

̶ I’d love to! And you can teach me German.

̶ It’s a deal. But only when my boyfriend’s in jail!

̶ Is he often in jail?

̶ Yes!

They look at each other and laugh. In the darkness, he steals a glance at her face, and is reassured: He knew she would either love or hate The Mother and the Whore, and by the glow on her face, he knows it’s not hate.

Jean-Pierre Léaud & Chantal Arbatchewsky (aka Nina Douchka), La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN: A CAROUSEL OF STILLS, IN SEQUENCE

JEAN EUSTACHE

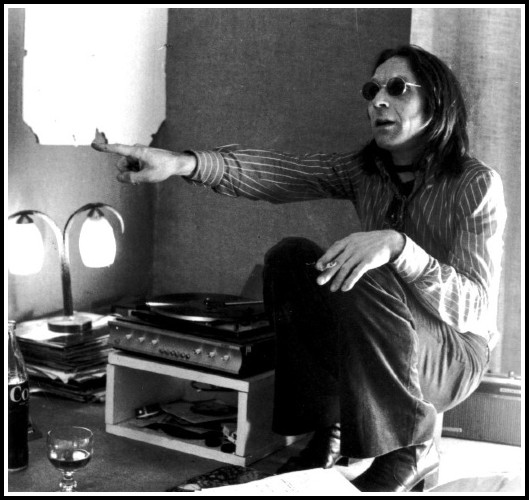

Jean Eustache moved to Paris in the early 1960s from his hometown of Pessac (Bordeaux). In Paris, he experienced the cinephilic frenzy of the Cinémathèque, while earning his living as a manual laborer, a railwayman or a garment deliverer. Married to a secretary at Cahiers du cinéma, he spent long hours in the journal’s office where he made the acquaintance of the Nouvelle Vague directors. Between 1963 and 1981, he made thirteen films that maintain a unity of vision despite their heterogeneity: La Maman et la Putain, a three hour-and-forty-minute film-fleuve; shorts on assignment that he inflected with his inimitably rigorous signature, regional documentaries, medium-length fiction films, a few shorts and a 35mm feature. ‘Ethnographer of his own reality,’ Eustache created a highly autobiographical cinema, even as he alternated between documentaries about local rituals, the most auteurist Parisian fiction ever created, and the provincial chronicle of a childhood. He referred to Dreyer, Mizoguchi, and Bressan as his models, but also recognized the influence of more popular filmmakers like Sacha Guitry and Marcel Pagnol. His suicide in 1981, though not surprising, triggered a lot of speculation. Whether it was because ‘cinema denied him’, as Luc Moullet wrote, or because his films, ruthlessly and bitterly personal, drained his vitality, in Serge Daney’s assessment, Eustache to the end remained the cinéaste maudit he could not help but be.

Abbreviated from Codruţa Morari, The Bressonians: French Cinema and the Culture of Authorship (Berghahn Books, 2017) pp. 87-88

JEAN-PIERRE LÉAUD

In Alexandre, an exquisite and hallucinatory young man with a line in verbal exhaustion, Jean Eustache offered Jean-Pierre Léaud the most striking role of his career. La Maman et la Putain, that absolute masterpiece, testifies less to the emancipation of Léaud from any pigeonhole than to the symbolic role that he would come to play for filmmakers who, confronting the legacy of the Nouvelle Vague, stake a claim to modernity. In other words, Léaud is a passeur, a conductor from one form of cinema to another.

Translated and edited for concision by Richard Jonathan from Jacques Mandelbaum, ‘Jean-Pierre Léaud ou l’art de la Fuite’ Le Monde, 19 January 2002

FRANÇOISE LEBRUN

Françoise Lebrun met Jean Eustache at a film festival where he was presenting his film, Les Mauvaises Fréquentations (1964). They decided to see each other again… On weekdays they would see three films a day at the Paris Cinémathèque, four a day over the weekend…They fell in love, lived together, separated, but kept in touch… ‘I had no desire to become an actress’ Lebrun says, ‘I became one for Jean, for this movie, for La Maman. Thanks to the film, I’ve travelled a lot. I’ve presented it all round the world—Buenos Aires, Mexico City, Melbourne. This year [2017] I went to New York and Tokyo. In fact, I don’t need to accompany the film anymore—it speaks for itself. But these trips are a form of thanks for the gift that Jean gave me. Each time, I meet people who have been moved, touched… Jean left a note on his door saying: “Knock loudly as if you had to wake up a dead man”. Before he killed himself, he had already made several suicide attempts. They were calls for help. That night, he went too far. He crossed the line. No one could have saved him.’

Translated and edited for concision by Richard Jonathan from Philippe Ridet, ‘A la recherche de Jean Eustache’, Le Monde 28 April 2017.

Veronika’s existence is painstakingly confined to her presence on the screen, and the little that we learn about her comes from the stories she recounts in a dispassionate voice fully of a piece with her languid body language. We never see her at the hospital where she works or in the nightclubs of Saint-Germain-des-Prés where she claims to be a regular. Her actions abide above all in verbal transactions. She is a ‘text’, the function and sum of words and sentences that she delivers with Bressonian blankness and flatness. Eustache insisted that she modulate her voice to sound like certain actresses in French film classics—Janie Marèse in Renoir’s La Chienne, for example, or Simone Simon in La Bête humaine. ‘From time to time,’ said Lebrun, ‘Jean would call to read me what he had written. He wouldn’t send me the text, but instead would recite it, which allowed me to feel what he wanted. The precision and the exactitude, the truth of what was written, this is what I was supposed to render.’

Edited for brevity from The Bressonians: French Cinema and the Culture of Authorship (Berghahn Books, 2017) p. 89

Françoise Lebrun

BERNADETTE LAFONT

‘When we were making La Maman et la Putain, the screenplay was so beautiful that we knew we were making something unique, a magnificent UFO’.

Translated by Richard Jonathan from Fabienne Bradfer, ‘L’éternelle fiancée parle du cinéma’, Le Soir (Belgium), 29 September 2003

ISABELLE WEINGARTEN

‘One falls in love with a woman,’ says Alexandre, ‘because she’s played in a Bresson movie.’ By employing a Bressonian model in The Mother and the Whore, Eustache engaged in an exercise in imitation, but also, and more importantly, reconfiguration. The director set Gilberte apart from other characters in the film while rewiring her within a different network. Unlike the film’s other post-68 destinies with their psycho-dramatic lives of disillusion and anxiety, Gilberte remains understated and oblique, very much in keeping with Bresson’s inimitable minimalism. In Eustache’s neurotic world, Gilberte stands out because she embodies ‘a sort of rigor and healthy constitution absent in the others,’ as Weingarten herself said upon the occasion of the masterpiece’s fortieth anniversary. Despite her palpable uncertainty and hesitation when Alexandre seeks to seduce her, she’s got her bearings. As an actress in Eustache’s film, Weingarten’s Gilberte provides a key to the movie: she is at once a Proustian creature and a Bressonian model.

Abbreviated from Codruţa Morari, The Bressonians: French Cinema and the Culture of Authorship (Berghahn Books, 2017) p. 88

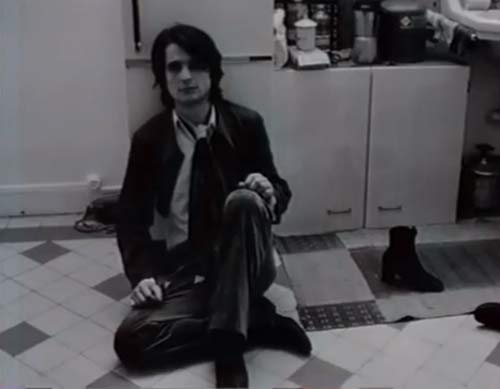

Isabelle Weingarten | Photo : Jeanloup Sieff, 1976

MUSIC IN ‘THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE’

In The Mother and the Whore, speech fails to express the essential: the feeling of love. That is why it is popular music—from times past (Damia, Fréhel, Piaf) or contemporary (Deep Purple, The Rolling Stones)—that fills this gap: in shy tenderness with Veronika, in the grandiloquent attempt at reconciliation with Marie.

Natacha Thiéry, ‘Éclipses du corps amoureux : Sur quelques films de Jean Eustache’ (Nouvelle revue d’esthétique 2012/2 n° 10) page 40. This excerpt translated by Richard Jonathan

Bernadette Lafont, La Maman et la Putain, Jean Eustache

FALLING IN LOVE AGAIN

Marlene Dietrich

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

I often stop and wonder why I appear to men

How many times I blunder in love and out again

They offer me devotion, I like it I confess

When I reflect emotion there’s no need to guess

Falling in love again

Never wanted to

What am I to do?

I can’t help it

Love’s always been my game

Play it how I may

I was made that way

I can’t help it

Men cluster to me like moths around the flame

And if their wings burn I know I’m not to blame

Falling in love again

Never wanted to

What am I to do?

I can’t help it

LES AMANTS DE PARIS

Édith Piaf

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Les amants de Paris couchent sur ma chanson

A Paris les amants s’aiment à leur façon

Les refrains que je leur dis c’est plus beau que les beaux jours

Ça fait des tas de printemps et le printemps fait l’amour

Mon couplet s’est perdu sur les bords d’un jardin

On ne me l’a jamais rendu et pourtant je sais bien

Que les amants de Paris m’ont volé mes chansons

A Paris les amants ont de drôles de façons

Les amants de Paris se font à Robinson

Quand on marque des points à coups d’accordéon

Les amants de Paris vont changer de saison

En traînant par la main mon petit brin de chanson

Y a plein d’or, plein de lilas

Et des yeux pour les voir

D’habitude c’est comme ça

Que commencement les histoires

Les amants de Paris se font à Robinson

A Paris les amants ont de drôles de façons

J’ai la chaîne d’amour au bout de mes deux mains

Y a des millions d’amants et je n’ai qu’un refrain

On y voit tout autour les gars du monde entier

Qui donneraient bien le printemps pour venir s’aligner

Pour eux c’est pas beaucoup car des beaux mois de mai

J’en ai collé partout dans leurs calendriers

Les amants de Paris ont usé mes chansons

A Paris les amants s’aiment à leur façon

Donnez-moi des chansons pour qu’on s’aime à Paris

UN SOUVENIR

Damia

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

De la merveilleuse aventure

Qui un jour a pu nous unir

Je garde malgré ma blessure

L’ineffaçable souvenir

Un souvenir

C’est l’image d’un rêve

D’une heure trop brève

Qui ne veut pas finir

Un souvenir

C’est toute la tendresse

Des beaux jours d’ivresse

Que l’on veut retenir

Un soir tu as pu te reprendre

Tout briser, tout anéantir

Mais pour moi qui ne sais comprendre

Qu’on peut mentir

Un souvenir

C’est l’image d’un rêve

D’une heure trop brève

Qui ne veut pas finir

Se souvenir c’est croire encore

Que tout vient de recommencer

C’est revoir l’être qu’on adore

Et retrouver tout le passé

LA CHANSON DES FORTIFS

Fréhel

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Fréhel

Le poète en guenilles

Les rodeurs et les filles

Des chansons d’Aristide Bruant

Les héros populaires

Les refrains d’avant guerre

Sont bien loin de nous maintenant

Tout cela disparaît dans la nuit

Et l’on se demande aujourd’hui

Que sont devenues les fortifications

Et les p’tits bistrots des barrières

C’était l’décor de toutes les chansons

Des jolies chansons de naguère

Où sont donc Julot

Nini, Casque d’or

Et P’tit Louis l’costaud

Si célèbre alors

Que sont devenues les fortifications

Et tous les héros des chansons

Des maisons de six étages

Ascenseur et chauffage

Ont r’couvert les anciens talus

Le P’tit Louis réaliste est devenu garagiste

Et Bruant a maintenant sa rue

Julot sera de l’institut bientôt

Et Nini possède un château

Il n’y a plus de fortifications

Ni de p’tits bistrots de barrière

Adieu décor de toutes les chansons

Des jolies chansons de naguère

Mais d’autres viendront

Héros différents

Puis disparaîtront

A chacun son temps

Il n’y a plus de fortifications

Mais y aura toujours des chansons

TOUT SIMPLEMENT

Vanni Marcoux

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Tout simplement comme une rose

Que l’on cueille un jour sans raison

Vous avez pris mon cœur morose

En passant devant ma maison

Mon cœur est une fleur d’automne

Sans savoir pourquoi ni comment

Vous l’avez pris, je vous le donne

Tout simplement

Vous avez à votre corsage

Mis la fleur de mon cœur rêveur

La fleur écoutait le langage

Et les regrets de votre cœur

Faisant plus douce son haleine

Sans savoir pourquoi ni comment

Ma peine endormait votre peine

Tout simplement

Sous le tendre amour qui l’effleure

Troublant votre rêve ingénu

La fleur a grandi d’heure en heure

Aux frissons de votre sein nu

Parmi les désirs et les fièvres

Sans savoir pourquoi ni comment

Elle a fleuri juste à vos lèvres

Tout simplement

Sous le baiser qui l’ensorcelle

La fleur a fleuri tout un jour

Votre bouche est rose comme elle

Le ciel se fait rose à son tour

Laissez-la vous baiser sans trêve

Et qu’un soir sans savoir comment

Elle meure avec votre rêve

Tout simplement

ICH WEIß, ES WIRD EINMAL EIN WUNDER GESCHEH’N

Zarah Leander

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Ich weiß, es wird einmal ein Wunder gescheh’n

Und dann werden tausend Märchen wahr

Ich weiß, so schnell kann keine Liebe vergeh’n

Die so groß ist und so wunderbar

Wir haben beide denselben Stern

Und dein Schicksal ist auch meins

Du bist mir fern und doch nicht fern

Denn unsere Seelen sind eins

Und darum wird einmal ein Wunder gescheh’n

Und ich weiß, dass wir uns wiederseh’n

Wenn ich ohne Hoffnung leben müsste

Wenn ich glauben müsste, dass mich niemand liebt

Dass es nie für mich ein Glück mehr gibt

Ach, das wär’ schwer

Wenn ich nicht in meinem Herzen wüsste

Dass du einmal zu mir sagst: ‘Ich liebe dich’

Wär’ das Leben ohne Sinn für mich

Doch ich weiß mehr

THE MOTHER AND THE WHORE | LA MAMAN ET LA PUTAIN

The complete film

Interview at Cannes

NATACHA THIERY: TWO BOOKS AND A RADIO BROADCAST (IN FRENCH)

NATACHA THIÉRY

Powell & Pressburger

NATACHA THIÉRY

Natacha Thiéry on Ernst Lubitsch

NATACHA THIÉRY

Lubitsch: Les voix du désir