In the Realm of the Senses

Nagisa Oshima, 1976

AROUSAL THAT NEVER ENDS: THE IMPOSSIBLE SEARCH

Maureen Turim on ‘In the Realm of the Senses’ (Nagisa Oshima)

From Maureen Turim, The Films of Oshima Nagisa: Images of a Japanese Iconoclast (University of California Press, 1998) pp. 132-37 and p. 34.

Maureen Turim is a Research Foundation Professor at the University of Florida.

Eiko Matsuda (Sada Abe) & Tatsuya Fuji (Kichizo Ishida), In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

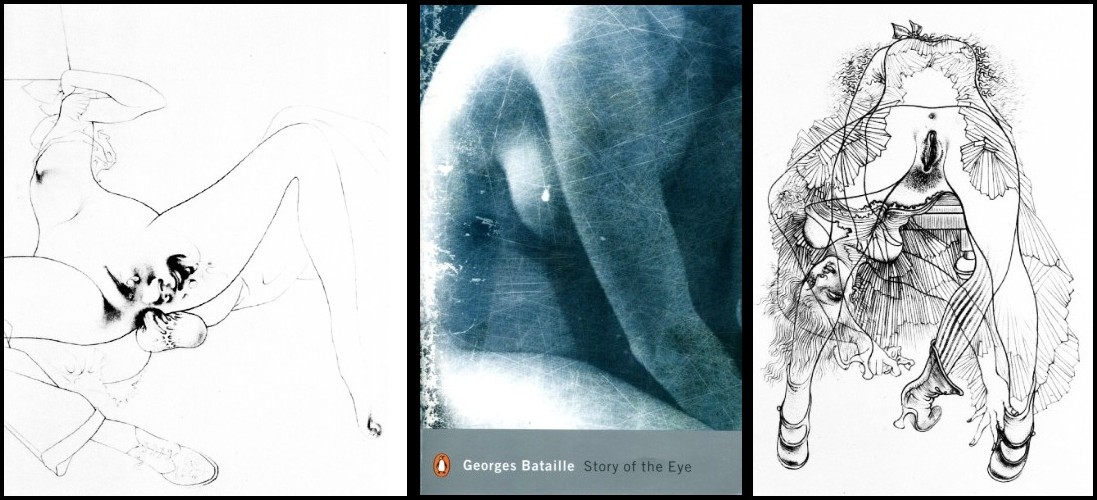

As in the writing of Georges Bataille, the fluids and tastes of sexuality are not only those produced by the body, but through an extension of the metaphor of appetite, echo symbolically as eating. The sexual play of food recalls the saucer of milk that elicits a bet between the young narrator and Simone at the opening of Bataille’s novel, L’Histoire de l’oeil (The Story of the Eye). This results in the narrator’s description of a nearly inoperable view, all the more erotic as one reads the verbal passage trying to imagine the logistics of seeing such a scene. He tells us he sees ‘her pink and black flesh bathing in the white milk,’ and if one wonders how, one retains the graphic image of the color contrast described. The image that follows immediately, however, secures the erotic in a more probable voyeurism, as Simone poses above him, a leg up on a bench, milk dripping down her thighs, as he masturbates on the floor below, culminating in their mutual orgasm, ‘without ever touching one another’. Bataille tells a story of the eye as sexual organ, using food as a supplement to a scenography in which taboos are broken ‘innocently’ as child’s play.

Georges Bataille, Story of the Eye | Illustrations: Hans Bellmer

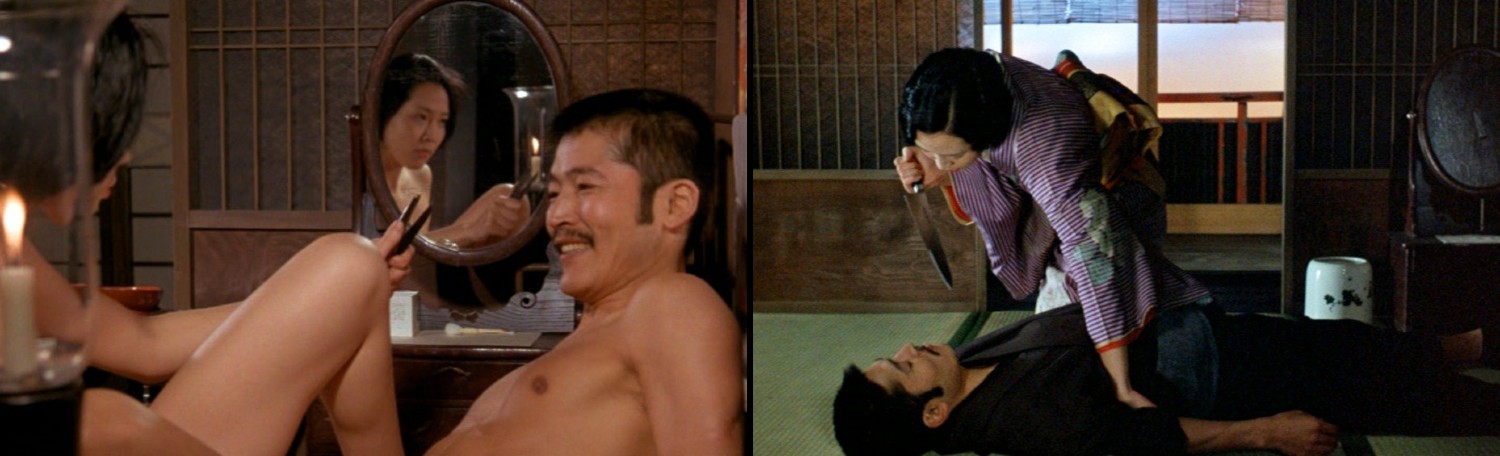

In a like manner, Kichi will use his chopsticks to dip food into Sada’s vagina as if were a sauce. Then an egg introduced by Kichi into her vagina will be laid by Sada, and she in turn will feed this egg to Kichi. If the metaphor for sexual hunger introduces a number of such substitute objects, the portrayal of female sexuality here is ambiguous.

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

If the vagina is a sauce, the scene of the egg becomes a mockery of female powers of reproduction and humiliates Sada.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

This recalls and prefigures variations on sexuality as humiliation and violence that occur elsewhere in the film, including two particularly violent sexual scenes that involve lesbian sexuality and two scenes that concern impotent men. When in the very beginning of the film her female co-worker at the inn makes a sexual advance, Sada responds at first with a refusal and later with a violent fight in the kitchen.

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

Later in the orgies following the mock marriage, a group of geishas rape a young woman with a dildo, a dildo that has the form of an elegantly decorated painted bird.

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

This fantasy of a violent female sexuality is symbolically crucial to the film’s realignment of sexual difference and the force of sexual drives within the gendered subject, for if Sada is to become the aggressor and Kichi is to become the willing passive object, this reversal happens in the context of these auxiliary sexual scenes. Lesbian desire or reaction to it seems to operate as a symbolic representation of excess as regards female desire. Women are active agents of sexuality, an agency that includes violent overflows.

Toku, Kichi’s wife, murdered in fantasy by Sada | In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

The aggressive female is joined as supplement by the passive and even masochistic male. In the beginning this male takes the form of the old man who begs Sada to touch his impotent organ.

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

Later in the film, Sada’s former client, to whom she returns to earn money for herself and Kichi, echoes the first man’s pathos. This client, whom she calls ‘Sensei’ (teacher), is an impotent masochist who asks Sada to hit him, introducing Sada to the sadomasochism that will spill over into her lovemaking with Kichi. [Note: Sada asks ‘Sensei’ to hit and pinch her. RJ]

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

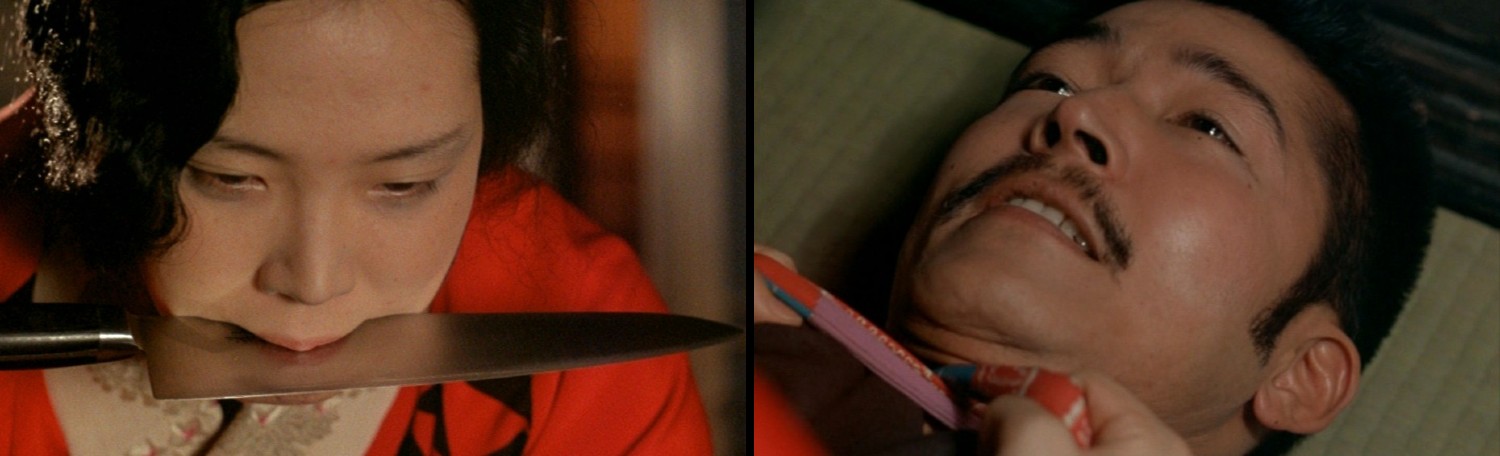

These supplemental scenes of violence and role reversals, along with a series of scenes of jealousy and possession, turn the seduction into a corrida, a bullfight. At different moments, Sada threatens Kichi with a scissors, makes love with a knife in her mouth, tells him she would like to cut off his penis to hold it always inside her. The constant demand for sexual arousal has become hers, the woman’s, and coupled with images of women’s aggression and men’s passivity, it becomes the driving force of the narrative.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

Biologically, the impossible sustained pleasure of a constant and ever-increasing orgasm is closer to the realm of possibility for the female. The male orgasm is temporally more finite and in need of time for recuperation; the female orgasm, of course, shares this quality of momentary presence and long absence but contains within its potential multiplicity the promise of the infinite. It is for this reason, perhaps, that the fetishism of Sada and Kichi’s sexuality shifts from the focus on the phallus itself to the phallus as instrumental in Sada’s pleasure. An earlier image of fellatio that frames the fluids dripping from Sada’s mouth cedes the way to other sexual acts that place other demands on the male organ.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

Both partners give themselves over to an ideal quest for Sada’s satiation, never, of course, possible, for that which Sada desires is to be perpetually aroused. Female orgasmic multiplicity, in being extended as perpetual arousal, meets impossibility, not only physiologically (the limits of the body), but logically: excitation needs both calm and release as defining contrasts.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

We can read this impossible ideal quest as metaphor of the centrality of desire to theoretical and fictional strategies of the postwar period. To theorize desire and to inscribe it become goals for societies not at all sure of what the twentieth century is doing to human desire; liberation, celebration, and the knowing of desire that previously had been stimulated by the novel, then by psychoanalysis, then by sex therapies and Hollywood films, are coupled with desire’s paradigmatic inversion, feelings of overwhelming powerlessness, futility, and impotence. In Japan this paradox might be seen in the popularity of the writing of Tanizaki…

Junichiro Tanizaki | La clef | The Key

… juxtaposed to the writhing bodies of Butoh, the modern dance form devoted to angst.

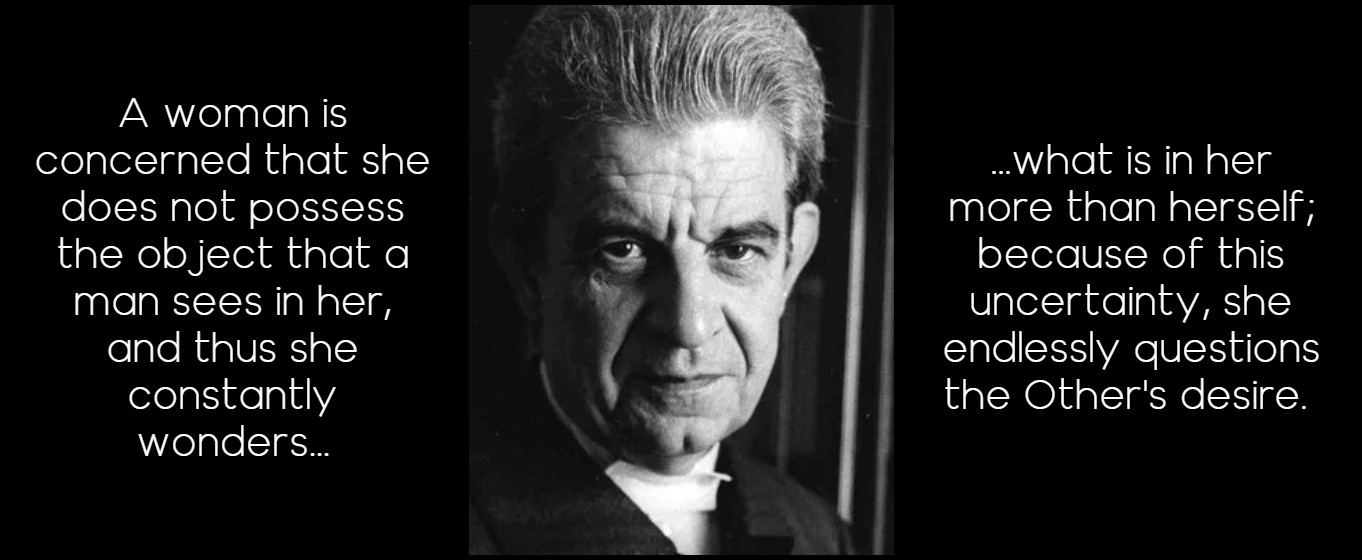

The film’s depiction of the impossible search for an object of desire that is a state of arousal that never ends, that is indeed ‘an object’ only in the sense of a point that might serve as aim or goal, but not in the sense of part object or love object, evokes comparison with a Lacanian notion of desire. Lacan’s seminars of 1956-1959 on desire began to theorize this conflict in light of the resurgent interest in de Sade as well as Lacan’s contemporaries, the writers Maurice Blanchot and Pierre Klossowski. Drawing on the Freudian principle of the inherently contradictory pursuits of excitement and stasis in orgasm, the idea of the drive and its aims that culminates in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Lacan posits the subject in just such a state of constant relation to the love object.

Jacques Lacan | Renata Salecl, ‘Love Anxieties’, in Barnard & Fink, ed., Reading Seminar XX, p. 94

In terming this object ‘petit objet a,’ Lacan draws it as an ephemeral end point in a diagrammatic formula of desire. Sada’s desire for constant arousal makes clear in extremis a displacement that is always a factor in desire; it is not the lover, the phallus, the vagina, or the fetish object alone one desires, but rather these objects as signifiers of desire, as provocative of one’s own sexual desires, one’s pleasures, and one’s satiation. Lacan, following Freud, proposes to explore how the phenomenological world of sensation affects the imaginary. Oshima gives us characters who are ciphers of a similar exploration.

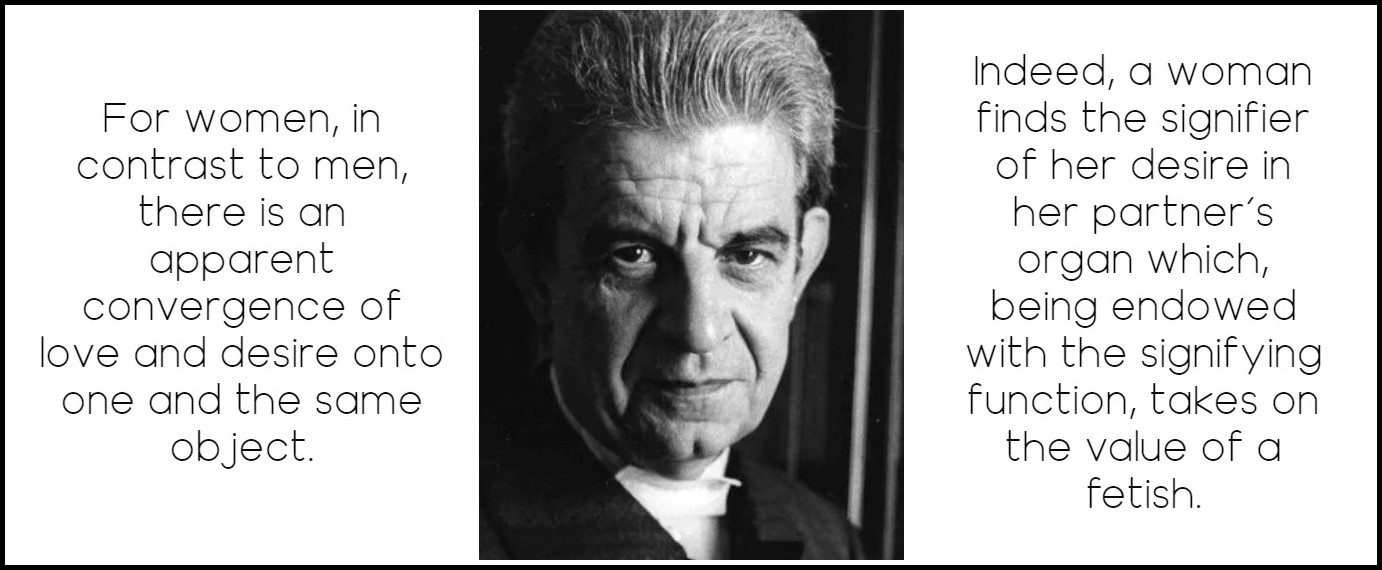

Jacques Lacan | Geneviève Morel, ‘Feminine Conditions of Jouissance’, in Barnard & Fink, ed., Reading Seminar XX, p. 79

In his 1959-60 seminar on the ethics of psychoanalysis, Lacan poses desire as a metonymy for the subject him- or herself, and he plays with the notion that those seeking power over the subject deny the subject his or her desire. Then he introduces the notion that the only thing of which one can be guilty, at least in a psychoanalytic perspective, is ‘to have given ground relative to desire’. Yet before reaching this point, he remarks on the failure, which he takes to be inevitable, of any libertine project of freeing desire, and he explores what the writings of de Sade tell us of an unmitigated acting on desire in its relationship to suffering. He is aware that desire inhabits a paradox: ‘On the far edge of guilt, insofar as it occupies the field of desire, there are the bonds of a permanent book-keeping, and this is so independently of any particular articulation that may be given of it’.

Jacques Lacan | Geneviève Morel, ‘Feminine Conditions of Jouissance’, in Barnard & Fink, ed., Reading Seminar XX, p. 81

Lacan’s treatment of the paradoxes of desire entailed in the problematic assumption by the subject of his or her own desire is relevant to our discussion here. Once Kichi and Sada have given themselves over to the unfettered exploration of each other’s desire, it is with these paradoxes that they experiment. Realm of the Senses is a film so deeply engaged in the exchange of desire that it perhaps proposes a consideration of theories of desire less bound to autonomous subjectivity. Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy (1993) and Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s desiring machines in A Thousand Plateaus (1987) might be seen as such attempts to free the energy of desire.

Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus | Jean-François Lyotard, Libidinal Economy

Lyotard emphasizes the flow of desire in all encounters and investments, championing particularly libidinal exchange in aesthetic experiences. In a sense, Lyotard desublimates the Freudian notion of sublimation, releasing libidinal investment in art, music, intellectual life, and so on, into a joyous self-awareness.

Jean-François Lyotard, Libidinal Economy, pp. 24-25

Deleuze and Guattari use apparatus metaphors to emphasize the automatic and constant flow of desire in humans constructed for just this purpose and to deconstruct any notion of central consciousness or unified subjectivity behind this desire, able simply to channel and control its flow. Their machine metaphor is meant to liberate human desire from Oedipalization and its attendant guilt and renunciation, structures that imprison creative desire through such confinement.

Deleuze & Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus, p. 183

Lyotard’s or Deleuze and Guattari’s theories might be suggestive for aspects of the film’s representation of desire. In particular, Lyotard’s theories might illuminate the relationship between sexual representation and sensual presentation, helping our understanding of the force of crescendo that builds in each episode of the film and across the film toward a climax, but which is only betrayed by stopping its invaginations with castration. It perhaps yields to this ending only to acknowledge the political aspects of a libidinal economy, limitations on pleasure imposed from historical and economic forces.

Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

The desiring machine metaphor in Deleuze and Guattari might be used to develop the inescapability and the mounting fascination that may begin with Kichi as motor force but flows to Sada. Kichi must go along with her drives not as submission but through an enmeshment that is seen as the fruition of multiplicities. The mechanics of their entwined desire is a machine larger than the simple union of two beings, a process Deleuze terms ‘destratification.’ Yet Deleuze and Guattari caution that ‘every undertaking of destratification (for example, going beyond the organism, plunging into a becoming) must therefore observe concrete rules of extreme caution: a too sudden destratification may be suicidal, or turn cancerous. In other words, it will sometimes end in chaos, the void and destruction, and sometimes lock us back into the strata, which become more rigid still, losing their degrees of diversity, differentiation, and mobility’.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

If all these theories can account for the film’s need to explore pessimistic turns of desire in addition to celebrating desire’s release, it is due to each theorist’s confrontation in his own manner with fascism and the excesses of capitalist drives. The film proposes, but does not rest on, a free-floating fantasy of unrestricted desire; the pursuit of desire as an endless end in itself is troubled not just at the film’s terminus in castration but throughout. For all its brashness and verve, for all its abstraction of character and crossing of gender identity, Oshima’s film always attends to the bleaker registers of desire, remaining far more a cautionary parable of desire, as well as one far more haunted by demonic fears, than an infinite bathing in passionate energies of unmitigated positive pleasure. If the castration conclusion of the scenario suggests a Lacanian investigation of desire more than those theories that might question the psychic reality and resolution of castration, what I find most intriguing is the suggestive ways the film opens to a rethinking of desire theoretically from several perspectives.

Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

It is with this theoretical range of perspectives on desire that we note that Sada, after returning from her client, urges Kichi to pursue the sadomasochistic game of a partial strangulation within their lovemaking, with her as the recipient of Kichi’s controlled and timed violence. However, this sadomasochism soon reverses roles, as Sada becomes the active violent partner, using her sash to cut Kichi’s breath, sustaining his erection, sustaining her pleasure. Breath, life itself, is cut in the pursuit of pleasure, and it is at this point in the film that Sada in a sense becomes a demon, preparing the way for the shift to the ghost story that will occur in Oshima’s next film, Empire of Passion.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES: A CAROUSEL OF STILLS, IN SEQUENCE

DONALD RICHIE ON EIKO MATSUDA

From Donald Richie, ‘Japanese Portraits’ (Tokyo: Kadansha Intl, 1984) pp. 36-39

Donald Richie (1924-2013) was a highly respected historian of Japanese film and culture. Fluent in Japanese, he lived in Japan for much of his life. Yet today, reading his ‘portrait’ of Eiko Matsuda, I am struck by the author’s utter insensitivity to the person in front of him, by his failure to see her as anything other than his image of her, an image that I find vulgar, cheap, and unworthy, one that dehumanizes Matsuda and trivializes both the film (in contrast to his excellent article on it on the Criterion Collection website) and Matsuda’s performance in it. Rather than a portrait of an actress whose talent and courage contributed so much to making In the Realm of the Senses an enduring masterpiece, Mr. Richie’s ‘portrait’, while as perceptive about Japan as one would expect from a recognized expert, is, when it comes to Eiko Matsuda, a self-indulgent, self-regarding exercise in style that tells us more about the author than it does about the actress.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

I present it here primarily to show the fate the film industry reserves for ‘erotic’ actresses who refuse to behave like ‘porn stars’, who will not conform to society’s ascriptions, who fly out of the pigeonhole they are put in; secondarily, because nothing else, as far as I know, has been published on Eiko Matsuda as a person, and Mr. Richie’s ‘portrait’ does, at times, escape the confines of his ‘frustration’. (For more on the question of society and its treatment of artists who don’t shy away from the expression of sex, see my post on Georges Bataille & Henry Miller and my article on Maria Schneider, referenced below.) You will find a deconstruction of Mr. Richie’s ‘portrait’ further down this page.

R.J.

In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

– Oh, no, I really much prefer Europe, she said, dark in the summer heat, turning to watch the sun slide behind Saint Peter’s.

I did not have to guess why. Many Japanese find freedom abroad but few had her reasons.

– It’s so interesting. And, of course, I have friends here.

Originally an actress in Shuji Terayama’s troupe, she was discovered by Nagisa Oshima and appeared in The Realm of the Senses, playing Sada Abe, strangling Tatsuya Fuji, cutting off his penis. Even though this scene, and many others, was missing when the film was shown in Japan, there was enough visible for newspapers and magazines to criticize.

Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

It was shameless. It wasn’t the way for a true actress to behave. And—perhaps the main motivation for the criticism—she seemed to be doing it all for foreigners, since it was they alone who were permitted fully to view the act. And yet it was a purely Japanese story. It was about, no matter what she might have done, one of our own. Why then was this cheap so-called actress exhibiting our shame abroad? Why was she behaving this way, was the question. The man was never criticized. He, Tatsuya Fuji, then a minor actor, found his career enormously assisted locally by the film. Thanks to it he went on to be a star, to appear in cigarette commercials, and he never again had to appear nude. Not so, however, in her case. She was a good actress, as she had proved, but no starring roles came her way. Only porno parts. She was also offered nude-dancer contracts. And more was suggested, amounts of money that would allow Japan to experience in the full flesh what had been denied it on the screen.

Tatsuya Fuji & Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

– Oh, no, that’s not the reason at all, she said, her skin brown in the failing light, Saint Peter, black: I don’t care what the press writes. If I did, well, I wouldn’t last very long. No, really. I like Europe. I have this little place of my own in Paris now. And I do like coming to Rome.

She sat there in the twilight—black dress cut low in the back, necklace of ebony and amber, good black leather shoes, good black leather bag. And I knew what was under all this elegance. For I too had seen the film and so her naked flesh was more real to me than the poised elegance now sitting beside me on a Roman balcony.

– It certainly wasn’t because of what they wrote. Actually, many women who’ve done less have had it worse. There were even some compliments—Nippon Sports called me brave. Did you know that? Well, they did.

Tatsuya Fuji & Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

She was very different from Sada Abe in the film. There, a housemaid, open, innocent, earthy, playing childlike games with the master. Now, black and elegant, chilled martini held between lacquer-nailed fingers, turning to speak in French to someone else, turning back to me to answer an earlier question.

– Every day? Oh, I shop. I see films. Friends—go to cafés, things like that.

She was brittle, sitting on the edge of the chair as though she did not belong there, as though she had only lighted, birdlike, on a flight to somewhere else, as though she might break if touched—and yet she was the same woman I remembered as all muscles, juice, and open thighs. Every lineament now stated a firm, polite request—do not touch me, her body said, each line an unmistakable refusal. She was as though immured in a sexless chic.

Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

And the real Sada Abe, had she too done this to herself? After she left the Inari-cho pub, she disappeared. The Nikkatsu film company had made a soft-core porn film out of her story and this had brought no complaints. Then Oshima had wanted to make his version and thought that he perhaps needed permission. She was discovered, after a long search apparently, in a Kansai nunnery—shorn, devout, and making no objections.

– It’s easy to make out that I’m some kind of martyr, run out of my own country, Eiko Matsuda said, smiling: But, believe me, it wasn’t like that at all.

One need not have one’s hair shorn to expiate, one could also have it newly coiffed. Her Paris dress was black as a nun’s habit. She had, in her own way, become Sada Abe; had paid something of the same price for doing so. There are various kinds of nunneries.

Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

ERICA X EISEN ON EIKO MATSUDA (AND DONALD RICHIE’S PORTRAIT OF HER)

Erica X Eisen

An extract from ‘Desire Vessel’ by Erica X Eisen, writer, editor, and journalist.

Eiko Matsuda got her start with Terayama Shūji’s theater troupe Tenjō Sajiki, which had positioned itself as the vanguard of the Japanese underground by mashing together such diverse influences as traditional folklore, jazz, and the short stories of Jorge Luis Borges. Tenjō Sajiki also frequently courted scandal due to the frank eroticism of its productions. Though at the beginning of her career—Matsuda was in her mid-twenties when work on In the Realm of the Senses began, a decade younger than her co-star—her prior experience had given her an understanding of avant-garde, politically daring art-making that set her apart. In interviews for the Criterion Collection, cast and crew members pointed to one thing in particular that crystallized Matsuda’s perspective for them: a tiny scorpion tattoo curled in the teardrop space of her earlobe. In a country where tattoos are so strongly associated with criminality that to this day it’s not uncommon for hot springs and beaches to require visitors who have them to cover up, Matsuda’s diminutive scorpion was a bold statement, a testament to her willingness to embody rebellion against the status quo.

Eiko Matsuda with scorpion tattoo on earlobe, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

The weight of the outrage at In the Realm of the Senses fell disproportionately on Matsuda. Even resoundingly negative reviews praised the actress for her commitment and emotional intensity, but public perception of her in Japan was of someone morally compromised, dirtied by her involvement, and unfit for serious film work. While Fuji went on to land the lead role in Oshima’s Palme d’Or-winning Empire of Passion (1978)—in many ways a spiritual successor to In the Realm of the Senses—his former co-star got offers for nude dancing contracts and porn films. Her once-ascendant star now seemed permanently to dim, and then to fall: dogged by press censure in her home country, Matsuda appeared in a handful of seedy ‘pink movies’ before moving to Europe, where, after making a final appearance in the minor French film Five and the Skin (1982), she left acting entirely.

Perhaps as remarkable as Matsuda’s performance and her sudden withdrawal from her craft is the fact that her story has gone largely unexplored by critics despite the global prominence of her best-known work. Both lay and scholarly writings on In the Realm of the Senses tend to confine themselves to her work in the film and give almost no consideration to what, for her, came after. The only real exception to this is the historian of Japanese film Donald Richie, who tracked down and interviewed Matsuda for an essay published in his 1987 book Different People. Richie rightly underscores the fact that Matsuda’s treatment in the press (and the subsequent drying-up of her career) differed sharply from the reception that greeted her male colleagues but, elsewhere in the piece, he replicates the very attitudes he criticizes.

Describing Matsuda’s tasteful dress and cultivated demeanor during their conversation, Richie notes in a leering aside that this was ‘the same woman I remembered as all muscles, juice, and open thighs.’ Elsewhere: ‘Her naked flesh was more real to me than the poised elegance now sitting beside me on a Roman balcony.’ The language here unapologetically sexualizes Matsuda despite occurring in the context of an essay that upbraids the Japanese film industry for failing to see her as anything more than a porn star; it is as though by agreeing to perform in the film Matsuda had signed up for the status of Permanent Sex Object. Richie is not the only one to regard Matsuda this way: at one point during the Belgian TV interview, the camera zooms in abruptly and lingers without explanation on Matsuda’s breasts.

Richie’s essay also construes Matsuda’s offscreen manner as a ‘sexless chic’ in which she is ‘immured,’ an inauthentic cover, he feels, for the true self she was allowed to express while playing Abe. Indeed, is it hard to reconcile the mousy, timid Matsuda of the Belgian TV panel with the bold uninhibitedness and confident physicality of her character? Well, only if one has difficulty imagining that an artist may have the power to invent. Here Richie makes the same mistake as Matsuda’s critics in Japan: an inability to distinguish between the artist and the art, a rhetorical projection of performance onto performer to the detriment, ultimately, of both. By conflating Matsuda’s personality with that of her character, Richie implicitly denies the actress artistry, interpreting her performance as a simple release of emotional energy rather than the intellectual product of a considered aesthetic and political position.

EIKO MATSUDA: INTERVIEW

Interview (Belgian TV): Nagisa Oshima & Eiko Matsuda

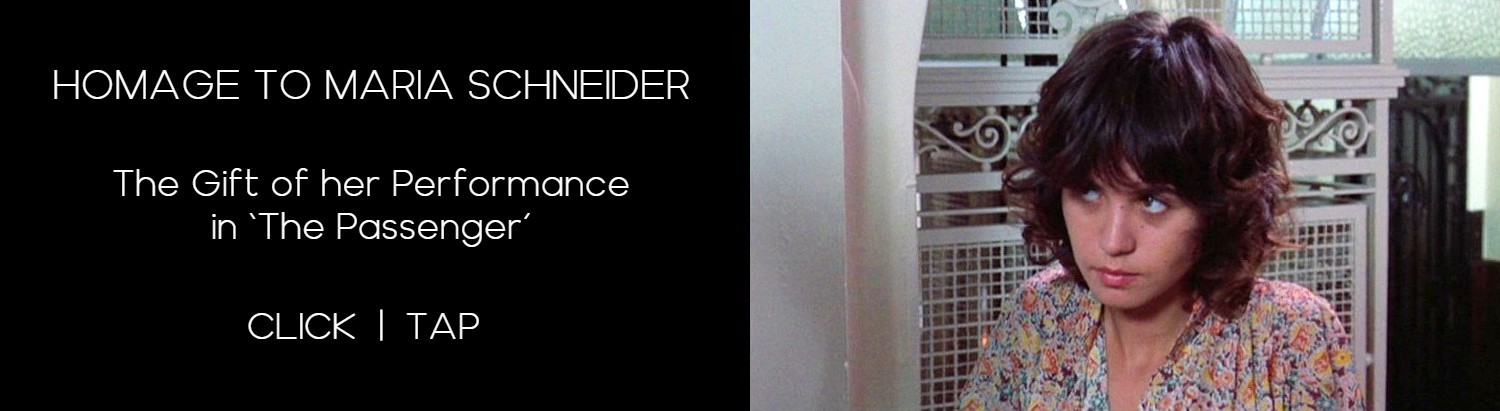

EIKO MATSUDA & MARIA SCHNEIDER: FILM AND ‘FATE’

Richard Jonathan

Both Eiko Matsuda (In the Realm of the Senses) and Maria Schneider (Last Tango in Paris, The Passenger) were born in 1958 and died in 2011 (aged 58). Matsuda died of a brain tumor and Maria of a lung tumor: grim deaths, still awaiting a worthy epitaph. While their brilliant performances shine on in the classics of global cinema they starred in, examining their ‘fate’ in the film industry brings up darker issues that need to be confronted. Why? So that actresses who display the daring these two did, actresses who serve art so admirably, may be celebrated instead of denigrated, embraced instead of banished. The acuity and finesse Erica X Eisen displays in her essay on Matsuda serve this cause well…

… while I make a more modest contribution in my mini-essay on Maria.

‘LIKE ALL TRANSCENDENCE, ART BRINGS SEX INTO PLAY’

Viviane Candas on Oshima’s ‘In the Realm of the Senses’

From ‘La révolution millénaire’ in « Lignes » 2018-3 n° 57, pages 85-96. This extract, from pages 92-93, translated by Richard Jonathan.

Viviane Candas is a French novelist and documentary and fiction filmmaker.

In the Realm of the Senses can be seen as a synthesis of the Japanese print, the myth of the vagina dentata and Georges Bataille, but here it is the woman, because of her all-consuming passion for the male organ, who is the executioner. The first time Kichi gets his hand up Sada’s kimono, he says, ‘You’ve got the pussy of a devourer’. Right from the get-go, then, he knows that this woman has castration and death in store for him. We, the spectators, are not immediately in the know, however, for it will take the entire duration of the film before we, caught up in a skillful mise en scène of the gaze, are in on the game. Throughout the first three-quarters of the film, the couple’s lovemaking is always observed by the women at the various inns they take a room in—the women who slip in a tray of tea, wait to clean-up, come in to sing—and spy on the couple from behind a screen. The center of the film screen is occupied by the sight line of these witnesses, which serves to free the spectator from the burden of his voyeurism—and thus of his shame.

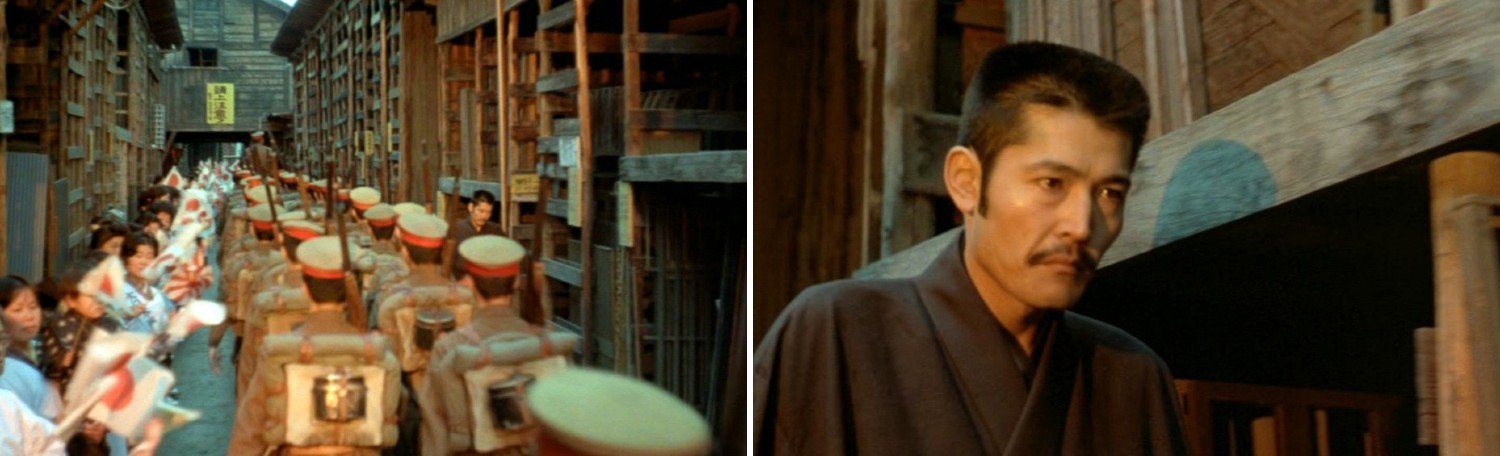

After Kichi and Sada each go out into the street (he walking against the flow of marching soldiers, blithely ignoring them; they, in their fascism, foreshadowing the film’s deathly ending), the lovers return and remain inside, never to be separated again. Nobody comes now to observe them. Why? Death is abroad, roaming off-screen but ready to enter instantly. And we, spectators who sense its presence, can do nothing to stop it, even if the lovers’ jouissance has transfigured us, we who find ourselves amongst the lovers and oppose the arrival of death because it would put an end to our ecstasy (as we observe the primal scene). If Oshima’s lovers devour each other with their eyes, it is because their eyes are their only organs with any perspective on their merged bodies. In the Realm of the Senses subverts the order of the world and the fear of the feminine, the hatred of women, that founds that order. The film does not satisfy the barbaric instinct of the spectator, but sends him back to his solitude, back to the limits of the human condition.

Like all transcendence, art brings sex into play; when it does not do so, it is stillborn. Efforts to expurgate sex from art show that censorship’s priority is to reduce the representation of female sexual power, the power that art sometimes delivers, even in a Balthus painting via a virginal girl’s panties that, as Nabokov said, disturbs only the viewer who would like to get his hands on the girl.

Balthus, Thérèse Dreaming, 1938

As in Molière’s School for Wives, all young women (except those born poor) would have to be sheltered to keep them out of earshot of the Sadian injunction: ‘Women are not made for one man only; it’s for all men that Nature created them’. If women are to be sheltered, then burn Marguerite Duras, whose heroines—from Hiroshima mon amour to The Man Sitting in the Corridor—repeat: ‘You’re killing me, you’re doing me good’. Yes, burn the Duras who dared to say that a woman who has never been ‘abused’* has not attained the foundation of her femininity. And Georges Bataille: ‘It is by shame, feigned or sincere, that a woman harmonizes herself with the prohibition that founds her humanity.’

* For the meaning of ‘abused’ in this context, see my blog post CATHERINE DENEUVE ACTRESS, PART 2 OF 4: ‘REPULSION’ (in particular, the section ‘The return of the repressed in four images from Repulsion’).

Delphine Seyrig, La Musica, Marguerite Duras

‘IN THE REALM OF THE SENSES’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM MARA, MARIETTA

Part Five Chapter 15

Ai no corrida: Shortly after the film’s release, shortly after your first night with Inès, you saw In the Realm of the Senses. It hit you hard. Walking at midnight in Saint-Germain, arm-in-arm under her umbrella, you paid no attention to the neon evanescent under your feet or the faces of the passers-by; no, all you could see as Inès led you to a bar were images of Eiko Matsuda making love to Tatsuya Fuji: Strumming the samisen as she sits astride him, she rocks him deeper into herself; with a languorous flutter of her eyes, she spills his sperm from her mouth; strangling him with the sash cord of her kimono, she sways as he twitches inside her. And the image of her, ecstatic upon her return to her dead lover, cutting off his cock with a butcher’s knife. And then the writing in blood on his body: ‘Sada, Kichi, the two of us together’.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

In a bar on rue Mazarin you ordered a Fernet-Branca with Bourbon and Angostura bitters; Inès opted for a Lillet blanc with Cointreau. Though she had made love with men, she’d never known pleasures like those you’d experienced with Jürgen and Marco. She interpreted your post-film emotion as revulsion; little did she understand what was stirring you. But she did perceive your fascination, and so talked freely about the film. She’d lived in Tokyo for seven years, she’d read the notes from the police interrogation of Abe Sada (published as a book), so when she confirmed that every detail in the film is drawn directly from Sada’s testimony, your stunned fascination gave way to elation, a buzz at once disquieting and liberating.

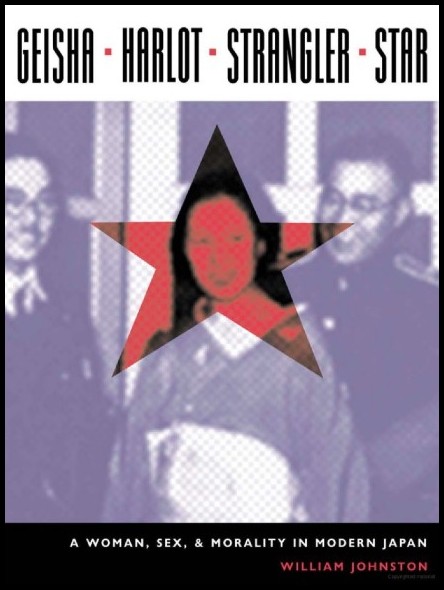

William Johnston, Geisha, Harlot, Strangler, Star

Needing a moment of silence, you angled your chair away from Inès and picked up your drink. As you savoured the subtleties of the bitters flavouring the Bourbon, you caught her reflection in a mirror: Tapering down around her face, her bob with its black sheen and purple glow framed her full lips and high cheekbones: You’d have kissed her then and there had not her cat-eye glasses kept her beauty from being overbearing. As you turned to face her she was a little confused, a lover not yet used to the intensity of your inner life. You asked her, as she sipped her Lillet, to tell you more about Abe Sada. ‘I want to know everything’, you said, ‘I love learning from you’.

Noboru Tanaka, A Woman Called Abe Sada | Nagisa Oshima, In the Realm of the Senses

It was with rapt attention, then, that you listened to the story of the woman who, thanks to the murder and mutilation she committed in her corrida of love, remains a compelling myth in Japan. What moved you most in her story was the way everything in her life—the years of prostitution, the gentleness with Professor Omiya, the intoxicating passion for Ishida Kichizo—seemed to derive from her parents’ failure to recognize her feelings when, at age fifteen, she was raped by an acquaintance. Indelibly branded as ‘damaged goods’, irrevocably unmarriageable, she sought, if not redress, at least recognition of what had happened: Her parents offered only indifference or calculating indulgence.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

In response, her anger became contempt; she decided to assume her fate and take her life in hand. Geisha, she couldn’t compete with the women who’d been training for that profession from childhood; whore, whether as licensed prostitute or freelance, she did fine; mistress, it all depended on the man. When she left the sex business she didn’t get farther than being a maid; her middle-class childhood was now the mark not of some paradise lost, but the demonstration that nobody was worthy of trust. Sex, whether in the business or out, had become her greatest pleasure; her desire knew no bounds. Was that a factor of biology, or a means to assert her freedom in the face of her destiny? Was it a facile rebellion against a society that had cast her out, or a search for the love and recognition she’d never had? That was the strand in her life that intrigued you, that and her overwhelming passion for Ishida Kichizo.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

With him, not only was sex bliss, but love was strong and recognition absolute. But he was married, he had children, he had a business to run. When the days of uninterrupted sex in the teahouses could no longer be maintained, Sada was not prepared to be relegated from his be-all and end-all to his mistress: With his tacit consent she strangled him to death, and in a delirium of what she construed as love, cut off the organ that had given her so much pleasure. When she realized what she’d done, she decided to hang herself; she was arrested, however, before she could carry out the act. It was not a double suicide that didn’t work out, it was one woman asserting her love over and against her lover and the world.

Tatsuya Fuji & Eiko Matsuda, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima

Inès assured you that the transcripts show she was neither a deranged pervert nor insane, but had, in her own words, done ‘insane things’ in the name of love. Was it because you saw your experience of anorexia as similarly insane that you were sympathetic to Sada? Did your experience of maternal abandonment dispose you to understanding not only her anger, but also her inability to let go of the man who finally assuaged it? Or was it that her quest for recognition from her father was a quest whose frustration you also knew? As you finished your drinks, you decided that next weekend you’d go and see the film again: Its beauty, at once lush and austere, had moved you, but the mystery of love at its core had moved you even more: That is what you wanted to immerse yourself in.

Eiko Matsuda & Tatsuya Fuji, In the Realm of the Senses, Nagisa Oshima