The American Soldier

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1970

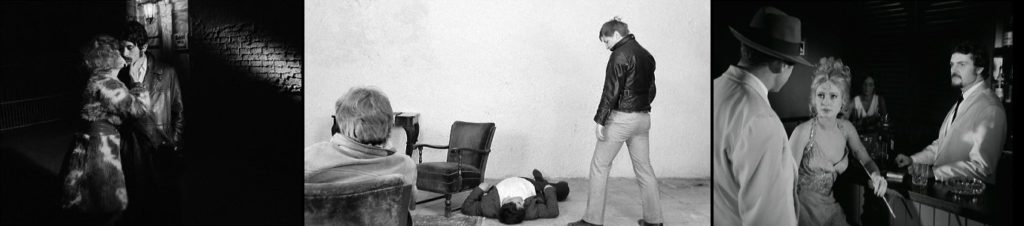

Gods of the Plague | Love Is Colder than Death | The American Soldier

GERD GEMÜNDEN ON FASSBINDER’S ‘THE AMERICAN SOLDIER’

Gangster Movies, Brecht, Hollywood, Parody & Pastiche

From Gerd Gemünden, Framed Visions: Popular Culture, Americanization, and the Contemporary German and Austrian Imagination (University of Michigan Press, 1998) pp. 94-101

Together with Love Is Colder than Death (1969) and Gods of the Plague (1970), The American Soldier (1970) forms a trilogy of gangster movies that demonstrate in exemplary fashion the multiple paradoxes of Fassbinder’s enterprise—paradoxes that are neatly contained in the name Franz Walsch. Frequently used by Fassbinder as a pseudonym for editing his films, it is also the name of the only character to appear in all three gangster films (twice played by Fassbinder, once by Harry Baer). A composite of Hollywood director Raoul Walsh and Franz Biberkopf, protagonist of Alfred Döblin’s novel Berlin Alexanderplatz (1929), the name epitomizes Fassbinder’s efforts to position himself between Hollywood gangster milieu and Weimar Proletariat, between American popular culture and German literary tradition. In The American Soldier Franz Walsch is the boyhood friend of Ricky, the protagonist who spells the name as follows to an operator: ‘I want a Munich number. Franz Walsch. Walsch—W as in war, A as in Alamo, L as in Lenin, S as in science fiction, C as in crime, H as in hell.’

Raoul Walsh | Alfred Döblin

All three films were produced by the antiteater as low-budget, low-key, black-and-white movies; all three are set in Munich and depict the life of outsiders on the fringes of the big city underworld: small-time pimps, professional killers, bar girls, porn dealers, and policemen who are almost indistinguishable from the gangsters they pursue. The American Soldier is a simple tale of a German-American Vietnam veteran, Ricky, who returns to his native Munich as a hired killer, carrying out his assignments with mechanical precision. He calls up his old friend, visits the scenes of his youth, and, in a pivotal scene, goes to see his mother and younger brother, before he is killed in a showdown with those who hired him and no longer need his services.

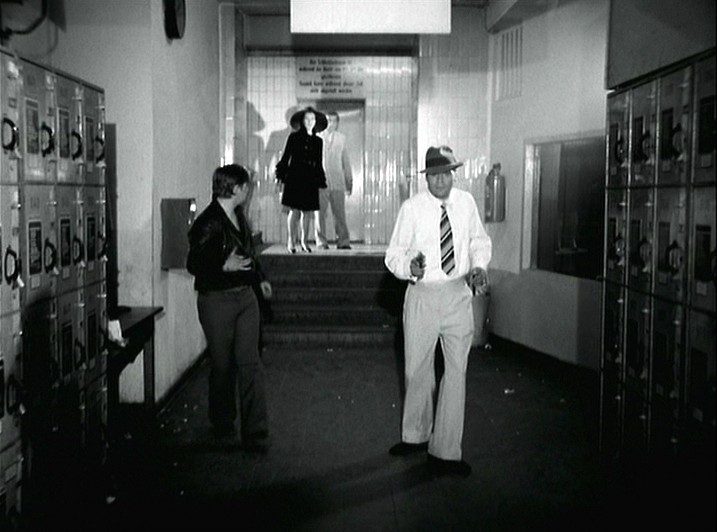

Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

The fundamental incongruity of setting an American thriller in Munich is quickly established at the beginning of the film and then exploited throughout. The film opens with a scene of three shady characters—later revealed to belong to the police force—playing cards under the smoke-filled light of a single low-hanging lamp. These are familiar types: the muscular boss, understated, obviously in command and winning; the sweaty and overweight underling who loses; the subservient intellectual with glasses, referred to as ‘Doc’. A blonde moll in the background rounds out the picture of this underworld quartet. The traces of heavy drinking are everywhere.

The police, The American Soldier, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

The phone rings, and the music flares up: ‘He’s here’. Cut to Ricky, whom the rolling credits introduce as the protagonist. He is entering town in a big white American cruiser, drinking whiskey from a bottle with a blonde next to him. Yet the film never delivers the drama that it promises, strangely subverting the traditions from which it so obviously borrows. Unlike in film noir, the killer/protagonist reveals no moral concerns underneath his macho shell, killing his victims at random and without remorse. The police are just as corrupt as he is. Moreover, the film contains virtually no suspense, not because it lacks action but because of its slow pace. While the first scene contains all the makings of a thriller, it doesn’t get off the ground: the close-up of the phone is just a little too long, the phone rings just a little too loud. The hero enters triumphantly, but we are not shown his face, which remains in the dark while that of the woman next to him seems lit by an artificial light source from below.

Irm Hermann & Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

When he throws her out of the car, he shoots her—but the bullets are blanks, thus strangely undercutting his image of a professional killer.

Irm Hermann & Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

The kind of displacement created here is quite different from Brecht’s plays, in which the drama is set in historic times or distant places in order to provoke comment or establish parallels on contemporary society. The Hollywood formula is invoked in a fashion that vacillates between nostalgia and parody—a homage to past times and the awareness of the pastness of those times that cannot be recuperated. One of the first things the American soldier says is: ‘It all began in Germany… Once upon a time there was a little boy… He who flew over the Big Pond… Dammit.’ It is as if the Vietnam War, invoked by the film’s title but never developed as a theme, is when for German intellectuals the United States lost its innocence. Significantly, Fassbinder abandoned the gangster genre after this film.

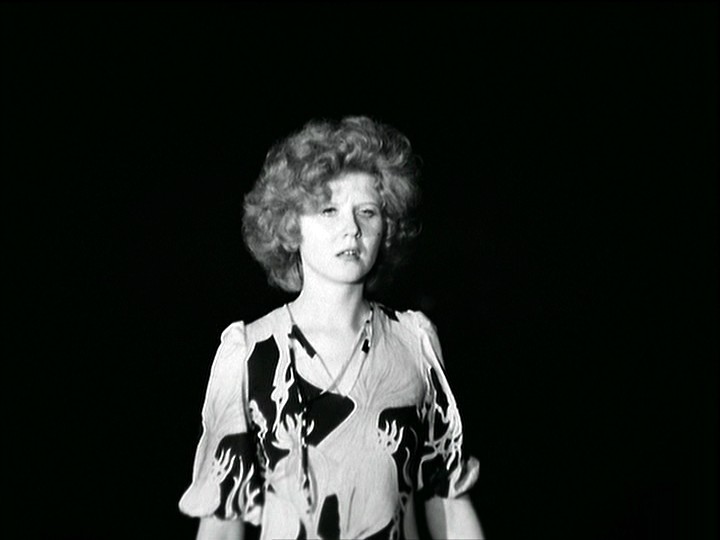

Irm Hermann, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

Like the other two gangster films, to which it provides a loose sequel, The American Soldier is a bleak, drab and dingy film, shot in long takes with long pans, creating a feeling of sadness, emptiness, and monotony. This sensation of flatness makes no pretense to realism, nor does the performance of the actors and actresses, who recite their lines without identifying with their roles. The deadpan diction and primitive epic form bear the mark of Brecht. Since these early films offset viewer identification, they have been read as examples of Brechtian strategies of Verfremdung (distancing), intending to maintain the viewer’s awareness of watching a performed reality.

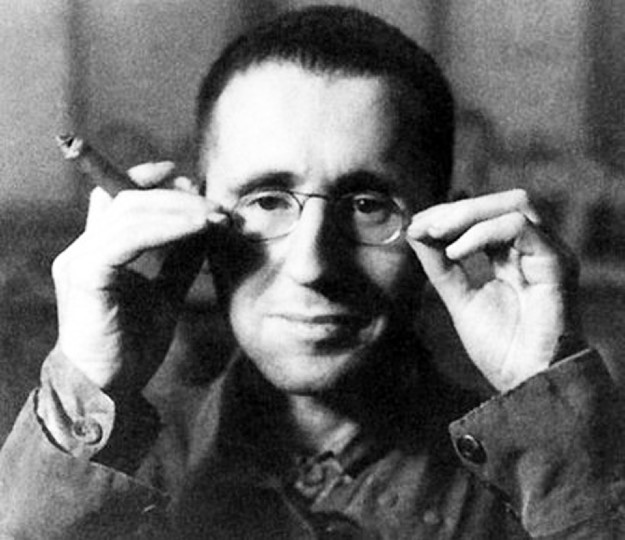

Bertolt Brecht

The stylized acting and mannered dialogues of these films undercut emotional involvement with the characters. As Anna Kuhn comments, ‘Unable to respond emotionally to the characters on the screen, the viewer tends to analyse the situation and to call into question the society responsible for it’. Even Kaja Silverman’s Lacanian reading of Gods of the Plague implies a recourse to Brechtian Verfremdung when she argues that Fassbinder refuses to naturalize the concept of identity by concealing its external scaffolding. By shifting the focus away from the spectator-character relation, Silverman claims, the film draws attention to the role of reflection and identification in the construction of identity. Yet the question arises whether the space created by offsetting viewer identification is at all available for productive criticism. In other words, do these films really provide the viewer with access to a viewpoint above or outside the performed reality?

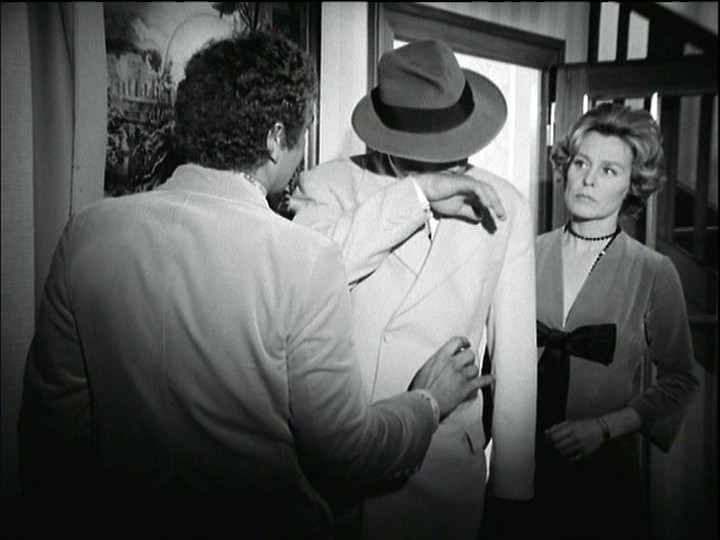

Margarethe von Trotta & Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

It is therefore important to understand to what degree films such as The American Soldier share Brecht’s notion of realism. We may recall that the Brechtian Verfremdungseffekt works to counter audience identification with the characters by foregrounding the artificiality of the performance in order to make the audience aware that it is watching ‘a play, mode of communication, a message’. The connexion between play and reality is, however, re-established when the engaged audience is impelled to investigate the characters’ behaviour and pass a moral judgement relevant to a reality that can and should be changed. The didactic purpose of epic theatre is to instigate intellectual reflection upon, and social intervention in, the existing conditions. This connexion between reality and representation is undermined in Fassbinder’s pessimistic and fatalistic gangster films, because they foreground how images and modes of representation constitute a certain reality, rather than understanding representation as a mere reflection or disguise of that reality.

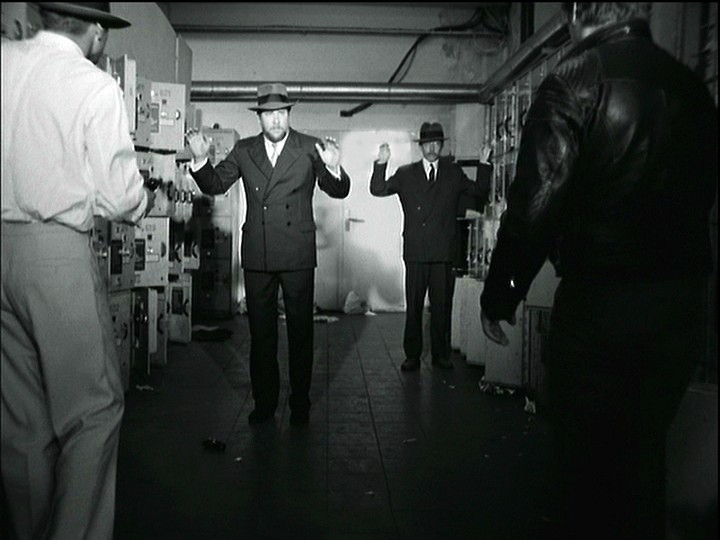

The police, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

Thomas Elsaesser has shown how one aspect of Brecht’s work, his notion of anti-illusionism, today seems particularly problematic, because it is based on an understanding of the real that our media culture has rendered obsolete. Television, film, and photography are media that no longer reflect or, as Brecht believed, distort truth but, rather, create events—not in the sense that everything we see on TV is pure invention. But for a political event to attain credibility it must be expressed through images and therefore must ‘pass through the process of sometimes intense specularity, with the paradoxical effect that, in order to become recognizable as political, events have to be staged as spectacle.’ This development from anti-illusionism to hyper-realism has significant repercussions for the Brechtian notion of critique. Since a position outside or above representation is no longer available, the mechanisms of identification that representation generates become highly ambiguous and paradoxical.

Hanna Schygulla & Harry Baer, Gods of the Plague, Fassbinder

In an interview, Fassbinder once explained, ‘I was not trying to imitate an American gangster film, but to make a film about people who have seen a lot of American gangster films’. This statement indicates that Fassbinder is more interested in mechanisms of identification and the construction of imaginary relationships than in undercutting viewer identification or the dismantling of the representation of false realities. It also stresses the historic dimension of Fassbinder’s infatuation with Hollywood cinema—often overlooked in psychoanalytic analyses such as Silverman’s—because it indicates how this cinema served, for him and his contemporaries, primarily as an imaginary realm, a medium for reflection and speculation, and crucial for establishing and maintaining an entire generation’s sense of identity.

John Huston, Asphalt Jungle, 1950

Excluding the real as ideological, Fassbinder’s remedy is to portray the artificiality of the artificial. All three gangster films abound with Hollywood clichés and icons. Love Is Colder than Death, for instance, features Bruno’s Ford Mustang and his stolen Cadillac; Bruno’s hat à la Alain Delon (who in turn seems to emulate Humphrey Bogart’s performance of Philip Marlowe); and Franz’s desire to have exactly the kind of sunglasses worn by the policeman approaching Janet Leigh in Psycho. In one of the film’s funniest scenes Bruno, Franz, and Joanna to a department store to steal sunglasses—the essential trademark of the Hollywood gangster. Putting on the sunglasses and taking them off becomes a self-conscious and ritualistic act, repeated many times throughout the film. Yet the subjects that mold themselves after Humphrey Bogart and James Cagney are taciturn and shabby, and show none of the heroic aura that surrounds Hollywood’s lonely heroes. They speak a language that is not theirs, turning the classical idiom and affirmative Hollywood discourse into a non-communication of platitudes. The few dialogues are punctuated by long silences, rendering any verbal exchange a monologue in which no one cares for a response.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ulli Lommel, Hanna Schygulla, Love Is Colder than Death

The American Soldier is extremely self-conscious in its quotation of Hollywood gangster rituals and icons of popular culture. It is not only the abundance of quotes, allusions, and references that startle—ranging from characters named Frau Lang, Murnau (as a voice on the phone), Rosa von Praunheim, Magdalena Fuller, Ricky (Rick being the name of Humphrey Bogart in Casablanca) to icons like a Batman comic read by a woman and shown in extreme close-up, the poster of a rock band decorating the police headquarters, and the pinball machine in the bourgeois home of Ricky’s mother—it is not this enumeration of quotes and objects, but their mode of employment that matters here. While individual scenes like Ricky’s shooting of the prostitute with blank bullets might be considered parodies, Fassbinder’s patchwork makes, on the whole, no satiric comment on its original material; if there is laughter, it is not a laughing at the characters but with the characters about the incongruity of their situation and their inability to cope with it.

‘Hallo, Murnau?’, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

Rather than calling the film a parody—a term that Fassbinder refused—it might better be understood in terms of what Fredric Jameson, in distinction to parody, has called pastiche: ‘Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar mask, speech in a dead language: but it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without any of parody’s ulterior motives, amputated of the satiric impulse, devoid of laughter and of any conviction that alongside the abnormal tongue you have momentarily borrowed, some healthy linguistic normality still exists.’ The underlying theoretical assumption is that parody, just as Brecht’s notion of anti-illusionism, is still informed by some belief in a master narrative that would legitimize a privileged critical stance. In Fassbinder’s cinematic reality this vantage point has vanished. The Brechtian search for truth and falsehood is acted out and confined to the level of the image. If politics have to be representable in order to be effective, then all that is left are politics of representation.

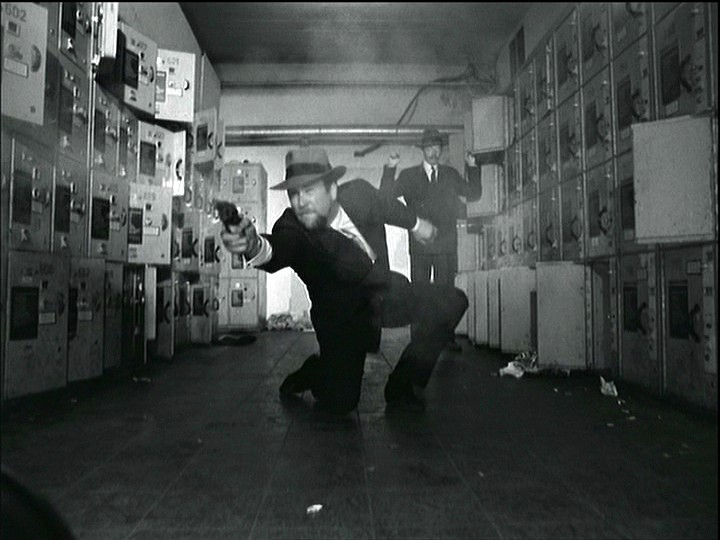

Pastiche in The American Soldier, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

In many ways The American Soldier was a calculated provocation, not only because of the conspicuous absence of any direct political comment about Vietnam in a film about a veteran of that war—all that Ricky has to say when asked, ‘How was the war?’ is ‘Loud’—but perhaps even more because of its aesthetics. Its stylized surface quality, it’s polished and deliberate flatness, is intended to deflect interpretation by rendering things and characters self-evident.

Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

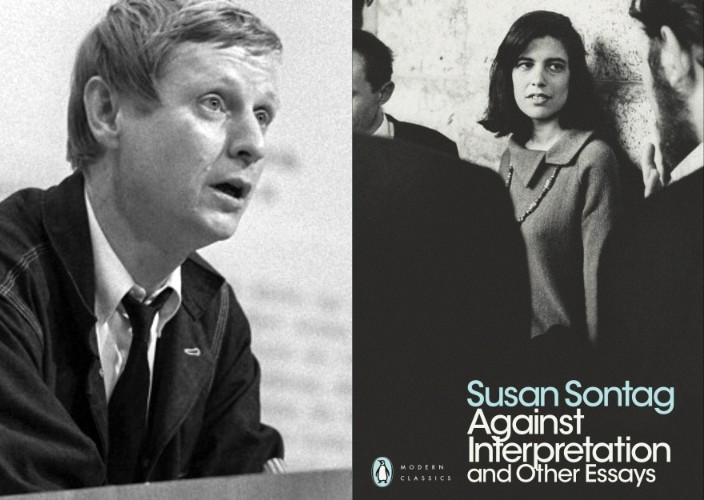

In its aestheticism and minimalism the film comes close to the position taken by Susan Sontag in her famous essay, ‘Against Interpretation’, in which she challenged the view that interpretation is necessary in order to achieve a resolution between the meaning of the text and the demands on the reader. Refusing the controlling and confining implications of a hermeneutics of suspicion, Sontag favored an ‘erotics of art’ that would ‘reveal the sensuous surface of art’. Written in 1964, Sontag’s essay today reads like a program for post-1968 West German literary and cinematic production, when after the failed student protest movement, writers and filmmakers abandoned the concepts of documentary literature and literature as social critique and political investigation. Instead of following Hans Magnus Enzensberger’s call for ‘the death of literature’, they staged a powerful resurrection of texts that turned their attention inward, onto themselves, seeking emotional authenticity and sensual experience.

Hans Magnus Enzensberger, 1968 | Susan Sontag, 1966

Sontag had believed film to be the most suitable medium to create an art ‘whose surface is so unified and clean, whose momentum is so rapid, whose address is so direct that the work can be just what it is’. The directors she singled out for their works’ ‘liberating anti-symbolic quality’—Walsh, Hawks, Cukor—were precisely those instrumental for Fassbinder’s, and also Wim Wenders’, sensibility. The young Germans reconsideration of classical Hollywood cinema was led by their appreciation of its immediacy and transparency, together with what they saw as its rejection of interpretation and simple-minded social critique—in Michael Rutschky’s phrase, a replacing of sense through sensuality. Writing about the Westerns of Raoul Walsh, Wenders marveled at how these films ‘brought out tenderness in a dreamily beautiful and quiet way. They respected themselves: their characters, their plots, their landscapes, their rules, their freedoms, their desires. In their images they spread out a surface that was nothing else but what you could see. “I’m never going back to El Paso”, says Virginia Mayo in a film by Walsh, and that’s all that is meant when she says that’.

Virginia Mayo, Colorado Territory, Raoul Walsh

The American Soldier is a film that reflects the Brechtianism of Godard and Straub but is also quite aware of the aporias of their position, as the vacillating between pastiche, nostalgia, and self-indulgence shows. It therefore already anticipates the coming change in Fassbinder’s position vis-à-vis Hollywood cinema and prepares the turn toward more audience-oriented films.

Rosel Zech, Veronika Voss, Fassbinder 1982 | Ingrid Caven, The American Soldier, Fassbinder 1970

GERD GEMÜNDEN: THREE BOOKS

AN ACROSTIC ON ‘THE AMERICAN SOLDIER’

Richard Jonathan

T is for tenderness, a damask rose in dung; a flower that’s ephemeral, yet more real than love.

H is for history, the nightmare from which RWF awoke: only to plunge back into with open eyes.

E is for exhaustion, exhaustion in the quest for redemption: 42 films in 17 years; dead at 37.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder & Karl Scheydt, The American Soldier, 1970

A is for antiteater: a community and its discontents, creativity from chaos.

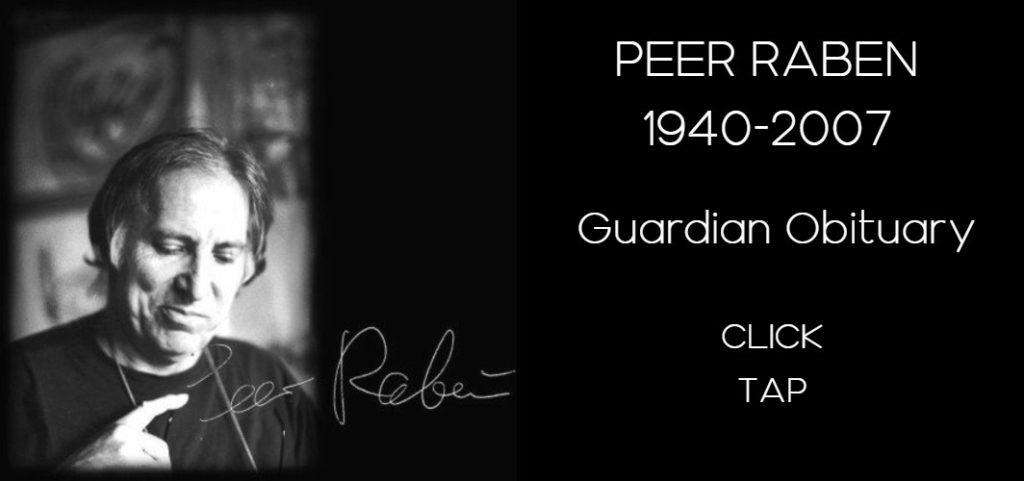

M is for music: Ingrid Caven and Peer Raben: poetry from pastiche, sincerity from tongue-in-cheek.

E is for ensemble: Hannah Schygulla and Margit Carstensen, Kurt Raab and Ulli Lommel, Harry Baer and Irm Hermann, among others: touched by grace, the time, the place—and the inspiration of he who blew hot and cold.

R is for Ricky, the hero who can’t tell the difference between love and violence.

I is for ‘I only want you to love me’: naked need clothed in celluloid.

C is for cinema, for the way RWF mastered the static in the kinetic, and so forged a style.

A is for articulate, the self-reflexive artist whose ordered intelligence contrasts with the chaos of his emotions.

N is for nine: the nine lives of the alley cat who lived in a wolf pack.

Karl Scheydt & Ingrid Caven, The American Friend, Rainer Werner Fassbinder

S is for SM: the head to the tail of solitude.

O is for obsession: the closed circle, the hothouse breeding pleasure and pain: in the end, only the works remain.

L is for love: love, colder than death.

D is for desire: the light that lives in darkness, the darkness that abides in light.

I is for inexhaustible, the inexhaustible need for love in this filmic universe.

E is for emotion: the heart stylized on the sleeve.

R is for reading, a life-saving passion. Alfred Döblin, Theodor Fontane, Heinrich von Kleist.

Kurt Raab, Karl Scheydt, Eva-Ingeborg Scholz, The American Soldier, Fassbinder

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

THE AMERICAN SOLDIER: SONG LYRICS

Our Love (So Much Tenderness) – Lyrics

Words: Rainer Werner Fassbinder | Music: Peer Raben | Singer: Günther Kaufmann

This song, and the scene to which it belongs, is emblematic of what is meant by ‘style’ in art. It is the artist’s fingerprint, the grain of his voice, the sign of the individual assuming his singularity. Without style, a work cannot transcend the material of which it is made; with style, conventions and rules can be flouted, the realm of possibilities expands. Style aims to please no-one but the artist himself: it is the imprint of the auteur. Without vision, however, style wears thin; without something to say, it is threadbare—it is vision that makes style compelling. (R.J.)

SPOTIFY: OUR LOVE (SO MUCH TENDERNESS)

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, The American Soldier, 1970

LYRICS: THE AMERICAN SOLDIER – OUR LOVE (SO MUCH TENDERNESS)

(Words transcribed as far as decipherable)

Our love is dead my friend

Our love has now an end

I feel this done my friend

And hope was born again

So much tenderness is in my head

So much loneliness is in my bed

So much tenderness over the world

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, The American Soldier, 1970

Thirteen days in the lower land

No chance for hand-in-hand

Life and sea are blue

Your words are never true

So much tenderness is in my head

So much loneliness is in my bed

So much tenderness over the world

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, The American Soldier, 1970

No more a lover in my arms

With my desire so far

No feeling for the time

The change for me’s unplanned

So much tenderness is in my head

So much loneliness is in my bed

So much tenderness over the world

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, The American Soldier, 1970

PEER RABEN ON COMPOSING & INGRID CAVEN

Source: ‘Peer Raben, Musicien des images allemandes’. Colette Godard, Le Monde, 14 April 1978. Translated by Richard Jonathan.

Composing music and directing plays, I proceed in the same way. I first establish the overarching rhythm, the contours of the piece. I might make major modifications during the course of the work, but I need a basic framework.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder & Ingrid Caven, Schatten der Engel, 1976

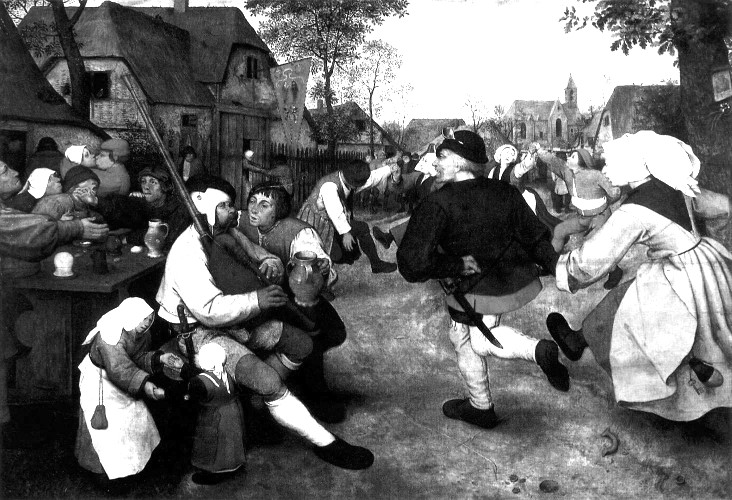

What I’ve learnt from composing for theater and cinema is that music has to do with duration. Theory teaches that a musical idea must pursue a development. It may happen that an idea is right, but that its development is too long. One can look for a different idea, or one can leave the idea only partly developed—an open form, just like in folk music where one can interrupt a piece and take it up again, ad infinitum. The beginning of a phrase is enough, the listener can complete it himself, as if he already knows the piece—it’s present in everyone. The same thing happens in Mozart, for example, but with him it’s a matter of drawing on cultural knowledge, whereas peasant dances like the gigue or the bourrée communicate immediately and directly.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Dance, 1567

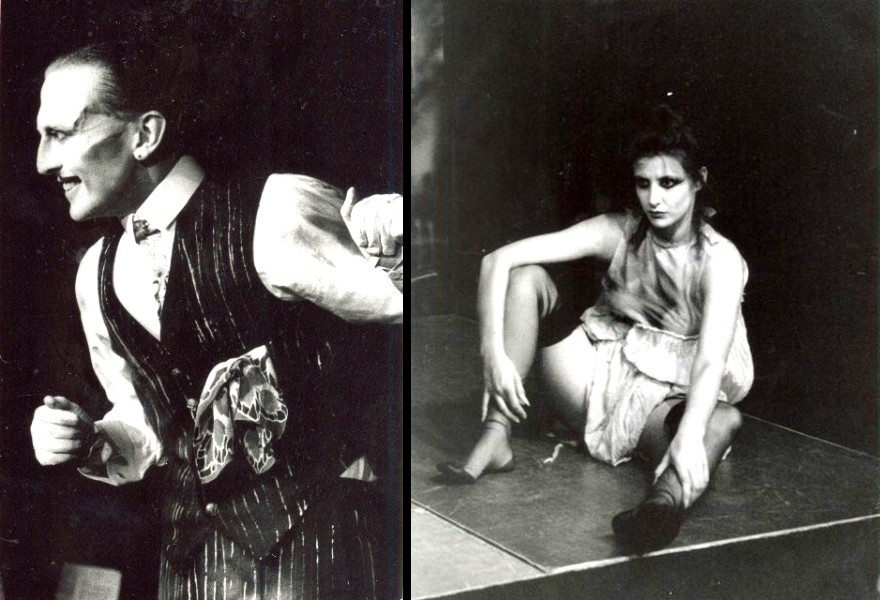

When I write for the theater or the cinema, I reinforce the images or I contradict them. Sometimes I disrupt them—I’ve learned a lot from Weill and Brecht. But their method is too intellectual. The Threepenny Opera would be even better if it were composed on the model of the light comedies of the twenties. That would be more honest. The dissonances show how far one has moved on from the world described. There’s a moralistic attitude in there that I don’t like.

Bench Theatre (Havant, UK), The Threepenny Opera, 1983

For the songs I composed for Ingrid Caven, it’s different. In fact, I prefer to think of them as lieder. A song is a snapshot, whereas the lied develops motifs. And then I wrote them for her, I cannot imagine them sung by anyone else. They show what she is—an aggressive, exuberant, excessive child. Provocative, because provocation for children is way into communication, a game. She is one of the strongest women I know. She says she needs other people. That’s a statement from someone who, in fact, needs no-one. Maybe I’m wrong, maybe she won’t recognize herself in my characterization, but that’s how I see her.

Ingrid Caven au Pigall’s

SPOTIFY: INGRID CAVEN AU PIGALL’S

You can listen to the tracks in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.