PART 1: I. INTRODUCTION | II. LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG: DIFFERENCES & SIMILARITIES | III. TWO SONG COMPARISONS

An Experiment in Comparison

LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG – PART 1

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

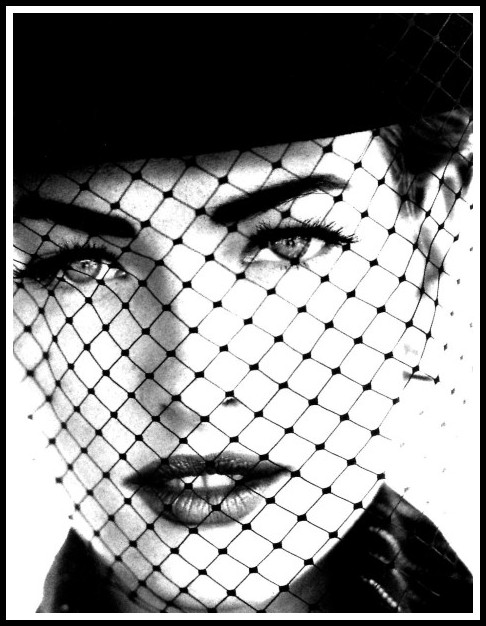

Dominique Issermann, Rebecca Romijn-La Perla, 1999

I. INTRODUCTION

Is there anything to be gained by comparing the songs of Leonard Cohen with those of Serge Gainsbourg? The aim of this essay is to find that out. I suspect there is—if only a fresh angle on certain aspects of the two artists—but to the extent that I cannot affirm that in advance, this essay is experimental. While I will adduce elements of the biographies into my argument, this will be strictly secondary to my primary method, which will be to argue from the evidence in the songs themselves. My hunch is that a comparison of just a few songs, focusing on the lyrics alone, will yield sufficient insight to make the essay interesting, and so I will limit myself to that. However, an overview of the differences and similarities between the two artists, insofar as they impact the songwriting, will prove useful: it will provide a contextual background for the songs discussed in the foreground, facilitating their interpretation. That is what I will offer in section 2. I will then, in section 3, compare six Cohen songs with six Gainsbourg ones:

1. Iodine | Les dessous chics

2. Light as the Breeze | Glass Securit

3. Take this Longing | L’Eau à la bouche

4. True Love Leaves No Traces | Je t’aime moi non plus

5. So Long, Marianne | Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

6. Chelsea Hotel #2 | La Javanaise.

Finally, by way of conclusion (section 4), I will briefly assess to what extent this experiment in comparison has or has not enabled us to see aspects of these artists from a fresh angle.

The essay is divided into two posts. This one is Part 1: the introduction, an overview of the differences and similarities between the two artists, and a comparison of the first two pairs of songs. The post of Part 2 compares the remaining four pairs of songs and provides the brief conclusion.

Note: My ideal reader will be bilingual; monolingual readers, I’m afraid, will have to draw on their own translation resources.

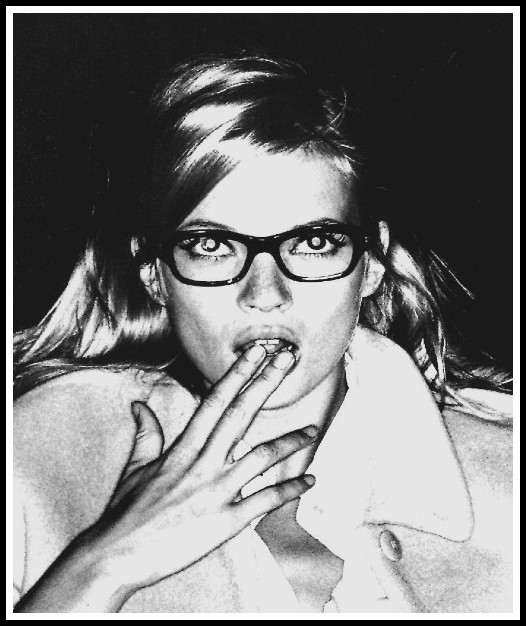

Vogue photo: Ellen von Unwerth, Nadja Auermann, 1991

II. LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG: DIFFERENCES & SIMILARITIES

Born six-and-a-half years apart, Serge in 1928 and Leonard in 1934, both artists are Jews of Russian background. Serge’s parents fled the Bolsheviks in 1921,1 as did Leonard’s mother (in 1927),2 while his great-grandfather had fled the pogroms (he arrived in Canada in 1860). Judaism, and its mystic strand in particular, was central in Leonard’s mythology, that syncretic accommodation of both the ethical and the numinous that infused his way of living. Serge, for his part, generally affirmed his Judaism more obliquely, as in the song ‘Juif et Dieu’. When push came to shove, however, Serge was more direct, as when he drew a parallel between a conservative editorialist’s denunciation of his reggae version of ‘La Marseillaise’ and the Dreyfus Affair.3 And, where Leonard published a volume of poems called Flowers for Hitler and evoked the Holocaust in many a song, Serge, who’d had to wear a yellow star in 1942, released an album called Rock Around the Bunker that addressed in each song an aspect of the Nazi regime, and more or less left it at that.

1 – Bertrand Dicale, Serge Gainsbourg en dix leçons (Paris: Fayard, 2009) Kindle Edition

2 – Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 3 & p. 6

3 – Bertrand Dicale, Serge Gainsbourg en dix leçons (Paris: Fayard, 2009) Kindle Edition

Vogue photo: Neil Kirk, Janine Giddings, 1995

When it comes to interpreting their songs, a critical difference between Leonard Cohen and Serge Gainsbourg is that where Serge always insisted that songwriting was a ‘minor art’, undemanding of its audience and ultimately vain and trivial, Leonard pursued what he invariably called his ‘work’ with the utmost seriousness. Indeed, for him, songwriting was nothing less than the primary vehicle in his pursuit of ‘sainthood’, that state of grace that arises when living brings forth the light: the infusion of the numinous and the ethical into the everyday. While both artists were scrupulous craftsmen, Serge had nothing against knocking off a song on demand—for a film, an actress, his record label, some singer—whereas ‘knocking off a song’ was something Leonard never could do: he’d often take years to finish a song. Why? My guess is that is has to do with Leonard’s immersion in Jewish mysticism, wherein, in studying the sacred texts, correspondences are traced between the worldly and the divine. It is his insistence that each song convey this duality that accounts in large measure for Leonard’s ‘slowness’ as a songwriter: one cannot force the light to come, but only make oneself available to receive it. This duality of worldly and divine—or more accurately, of the divine in the worldly—is evident in just about every Cohen lyric. Gainsbourg’s lyrics, in contrast, lack this vertical dimension, that axis mundi via which the poet moves between the realms of heaven, earth and underworld. There is, of course, duality in Serge’s lyrics, but it is horizontal in nature, consisting in the poetic construction of the lyric and in the displacement of the face-value meaning of words for the purpose of punning. To simplify, we can say that Leonard’s lyrical genius consists in constantly holding worldly and divine in tension—never one without the other—whereas Serge’s consists in brilliant play with the French language—never submission to it without subversion of it.

Vogue photo: Ellen von Unwerth, Nadja Auermann, 1991

In their attitude toward their audience, evident in their songwriting, Leonard Cohen and Serge Gainsbourg differed greatly. Serge always considered himself a failed painter—Francis Bacon was his ideal of the artist—and this failure was a chip on his shoulder. This lingering bitterness was reinforced by the commercial failure of many of his most personal albums.1 He also happened to consider himself ugly. In the face of this, he adopted a persona of cynicism and misogyny, and because he expressed that persona with stylish wit, he charmed his audience. In his last years, however, the vulnerability that his persona couldn’t suppress gave way to a mean-spirited braggadocio, vain and empty boasting about his fucking, whether of (never with) Lolita-like girls, wasted whores, or attractive women he’d cut down to size.2 Given that he suffered from alcohol-induced impotence,3 his obsessive bragging made him a pitiful figure.

1 – Bertrand Dicale, Serge Gainsbourg en dix leçons (Paris: Fayard, 2009) Kindle Edition

2 – I’m referring to songs on Love on the Beat (1984), as well as others, as performed in 1986 at Casino de Paris and to songs on You’re Under Arrest (1987), as well as others, as performed in 1988 at Le Zénith (Paris). Both concerts are available on DVD.

3 – Loïc Picaud & Gilles Verlant, L’intégrale Gainsbourg: L’histoire de toutes ses chansons (Paris: Éditions Fetjaine, 2011) p. 631

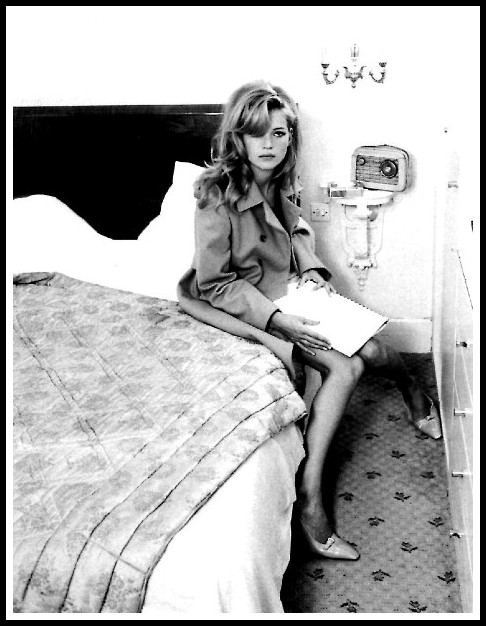

Vogue photo: Corrine Day, Erika Wall, 2000

Leonard Cohen, for his part, was a unfailingly true to himself, engaging with his audience on his own terms. Like Serge Gainsbourg, he too had known chronic commercial failure (in the land of the record business and biggest potential market, the USA) but, unlike Serge, Leonard was doing exactly what he wanted to do in the way he wanted to do it1 and his measure of success, one might say, had more to do with the quality than the quantity of is audience. Consequently, Leonard did not vaunt his exploits and seek adulation the way Serge did; instead, being inner-directed and secure against outside ascription, he was invariably modest and self-deprecating: his concern was not with ‘how large we are against the sky’ but with ‘how small we are between the stars’.2 This, then, is a crucial difference between the two artists: where Serge’s dissatisfactions made him dependent on outside ascription,3 that need eventually coming to govern his work, Leonard, for his part, embraced his pursuit of saintliness, irrespective of the vagaries of audiences and the record business.

1 – With the exception of the Phil Spector episode, the making of Death of a Ladies’ Man (1977).

2 – Adapted from Leonard Cohen, ‘Stories of the Street’. Songs of Leonard Cohen (Columbia Records, 1967)

3 – Serge needed, in equal measure, acclaim from some and castigation from others.

Vogue photo: Ellen von Unwerth, Tatjana Patitz, 1991

In a 2001 interview with Stina Dabrowski,1 Leonard Cohen articulated a key aspect of his attitude towards women and relationships. As we shall see in the song comparisons, his attitude differs greatly from that of Serge Gainsbourg. I therefore quote from the interview at some length:

You tried to kill the lady’s man in the seventies already—’Death of a Ladies’ Man’.

Well, women took care of that! I didn’t try to kill anyone. I felt I got creamed. But everybody has the feeling of the disaster of the heart, because nobody masters the heart. Nobody’s a real lady’s man, or a love gangster. Nobody really gets a handle on that. Your heart just cooks like shish kebab in your breast, sizzling and crackling—too hot for the body.

So how did you feel?

Well, the reputation [of lady’s man] was completely undeserved. I don’t think my concerns about women and about sex were any deeper or more elaborate than any other guy that I met. Women are the content of men and men are the content of women. So everybody’s involved in this enterprise with everything they’ve got. And most are hanging on by the skin of their teeth. As I say, nobody masters the situation. Especially if it really touches the heart—then one is in a condition of anxiety most of the time. And even the great lady’s men that I’ve bumped into—and I’ve met some real ones—the sense of anxiety about the conquest is still very much there. Because in any case, the woman chooses.

1 – The quote in question starts at 27m05.

Ellen von Unwerth, Kate Moss, 1995

How?

I think the woman chooses. It’s been told to me that the woman chooses and she decides within seconds of meeting the man whether or not she’s going to give herself to him. In any case I think that in most cases the woman is running the show in these matters. And I’m happy to let them have it.

So there you have it, dear reader. The woman chooses. The woman decides within seconds of meeting the man whether or not she’s going to give herself to him. She is running the show. And if Leonard is happy to let her do so, Serge, as we shall see, will have none of it. This fact alone goes a long way to explaining the differences between the two songwriters that we observe in their songs.

Ellen von Unwerth, Kate Moss, 1995

III. LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG: SIX SONG COMPARISONS

1. IODINE | LES DESSOUS CHICS

IODINE

Leonard Cohen

I needed you, I knew I was in danger

Of losing what I used to think was mine

You let me love you till I was a failure

You let me love you till I was a failure

Your beauty on my bruise like iodine

I asked you if a man could be forgiven

And though I failed at love, was this a crime?

You said, ‘Don’t worry, don’t worry, darling’

You said, ‘Don’t worry, don’t you worry, darling

There are many ways a man can serve his time’

You covered up that place I could not master

It wasn’t dark enough to shut my eyes

So I was with you, oh sweet compassion

Yes I was with you, oh sweet compassion

Compassion with the sting of iodine

Your saintly kisses reeked of iodine

Your fragrance with a fume of iodine

And pity in the room like iodine

My masquerade of trust was iodine

And everywhere the flare of iodine

Yes, it started with the flare of iodine

LES DESSOUS CHICS

Serge Gainsbourg

Les dessous chics

C’est ne rien dévoiler du tout

Se dire que lorsqu’on est à bout

C’est tabou

Les dessous chics

C’est une jarretelle qui claque

Dans la tête comme une paire de claques

Les dessous chics

Ce sont des contrats résiliés

Qui comme des bas résillés

Ont filé

Les dessous chics

C’est la pudeur des sentiments

Maquillés outrageusement

Rouge sang

Les dessous chics

C’est se garder au fond de soi

Fragile comme un bas de soie

Les dessous chics

C’est des dentelles et des rubans

D’amertume sur un paravent

Désolant

Les dessous chics

Ce serait comme un talon aiguille

Qui transpercerait le cœur des filles

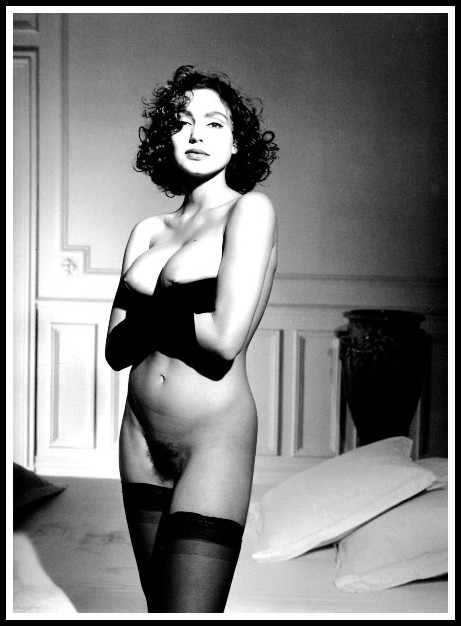

Bettina Rheims, Claudya with Gloves, 1987

Both these songs address the artists’ respective breakups with their long-term partners, Leonard Cohen’s with Suzanne Elrod and Serge Gainsbourg’s with Jane Birkin. After nine years together (1969-1978), during which they had two children, Leonard and Suzanne separated. ‘Although they were never legally married, in 1979 they divorced’.1 Serge and Jane had one child and broke up after eleven years together (1969-1980). In both cases, it was the woman who left the man (which, for both artists, was the exception that proved the rule). Leonard recorded ‘Iodine’ in 1977, and Serge had Jane record ‘Les dessous chics’ in 1983 (his own version was recorded live in 1988). There’s a fine twist, as we shall see, to these biographical parallels between the two couples: Cohen’s song is very ‘Gainsbourgien’ and Gainsbourg’s is very ‘Cohenesque’.

1 – Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 297

Vogue photo: Ellen von Unwerth, Tatjana Patitz, 1991

‘Iodine’ belongs to the sequence of songs that make up the album Death of a Ladies’ Man.

Sylvie Simmons: ‘At the core of Death of a Lady’s Man is the story of a marriage, and the capacity of this particular union (whose rise and fall are digested in the poem ‘Death of a Lady’s Man’, much as they were in the album’s title song ‘Death of a Ladies’ Man’) to both heal and wound’.1

Leonard Cohen: ‘I think marrying is for very, very high-minded people. It is a discipline of extreme severity. To really turn your back on all the other possibilities and all the other experiences of love, of passion, of ecstasy, and to determine to find it within one embrace is a high and righteous notion.’2

Marriage and its discontents is indeed the theme of ‘Iodine’, with wounds and (simulacres of) healing the main motifs.3

1 – Simmons, p. 295

2 – Simmons, p. 268

3 – In what follows I will use, for the sake of readability, the names ‘Leonard’ and ‘Suzanne’ to refer to the protagonists of the song, while being well aware that the real-life people and the characters in the lyric are not necessarily congruent. Same goes for my use of ‘Serge’ and ‘Jane’ later on.

Vogue photo: Helmut Newton, 1997

‘You let me love you’: The woman chooses. ‘Till I was a failure’: Leonard’s pursuit of sainthood takes precedence over the maintenance of a marriage; as long as that is true, failure in marriage is inevitable.1 Who was kidding who that it could be otherwise? ‘I needed you, I knew I was in danger / Of losing what I used to think was mine’: Leonard, in yielding to his need to include in his ‘ identity’ whatever it is that Suzanne provided, kidded himself. He violated his integrity, and so he is bruised. Her beauty, no less resplendent, is a violet stain that marks her victory since, unlike his integrity, it is undiminished. Note the asymmetry here: the man operates on a moral plane; the woman, because her beauty is sovereign, transcends ethics. ‘I asked you if a man could be forgiven / And though I failed at love, was this a crime?’: The woman not only chooses, but in the sovereignty of her beauty, also pronounces judgement: ‘There are many ways a man can serve his time’.

1 – The situation—toute proportion gardée—is analogous to that of Christ in The Last Temptation of Christ, as depicted in both the Nikos Kazantzakis novel and the Martin Scorsese film: for one who desires sainthood, marriage is tempting, but in the end it’s simply not an option.

Vogue photo: Richard Avedon, Lauren Hutton, 1969

And yet there is ‘a place’ that Leonard ‘could not master’—some kind of vulnerability that induces compassion, ‘compassion with the sting of iodine’. Iodine, in the song, is the emblem of wounding and double dealing; with both Leonard and Suzanne in a state of disgrace, there can be no healing. Neither able to ‘come clean and be honest with each other’ nor to ‘sweep the deception under the carpet’, the couple in this relationship confirms the adage that marriage is a conspiracy between two people to make communication between them impossible, or, to put it more kindly, that marriage is a machine that impedes communication in a couple. Leonard’s stance in the ‘marriage’ is marked by passivity and obliqueness, which enables him to be coy about accepting his share of responsibility for what’s gone wrong. Indeed, if, in his pursuit of sainthood, he must fall under the sway of a woman’s beauty, how can he be held responsible for what goes wrong? It is she in her beauty that is sovereign, not he. Remember, it is the woman who chooses to give herself to the man or not. When things go wrong in the relationship, her weapon of choice, she soon understands, is not to withhold, but to give in a way that humiliates. When a man accepts these terms, everything he accepts from the woman is marked with the stain of iodine—the violet of the woman’s victory. Under these conditions, as long as the man remains in the ‘marriage’, he can only lose. And thus it is that iodine marks the entry of the relationship into its terminal phase.1

1 – Sad and bitter, ‘Iodine’ brings to mind Lou Reed’s ‘Sad Song’, where the lover sings:

She seemed very regal to me

Just goes to show how wrong you can be

I’m gonna stop wasting my time

Somebody else would have broken both of her arms

Note that Leonard, unlike Lou, refuses to renounce the sovereignty of beauty, and that Lou, unlike Leonard, refuses to unequivocally renounce violence.

Vogue photo: Wayne Maser, Carré Otis, 1988

Jane Birkin: ‘The song ‘Les Dessous chics’ really is a portrait of Serge. It represents the modesty of feelings, made up outrageously in blood red. It’s about keeping one’s true feelings deep inside, as fragile as a silk stocking.’1 ‘I am singing his hurt, I become l’homme à tête de chou, I am Serge in disguise’.2

I said earlier that Cohen’s song is very ‘Gainsbourgien’ and Gainsbourg’s is very ‘Cohenesque’. Let’s now unpack that. In ‘Iodine’, the man’s bitterness as he speaks of iodine—the emblem of the woman’s victory in her war with the man—is a typical Gainsbourg stance, as is the ‘violence’ of the metaphor itself. In ‘Les dessous chics’, the subtlety and finesse of the cut-glass lyric is typical of Cohen’s style, as is the imbrication of the metaphysical in the physical—in this instance, the man’s hurt in the woman’s underwear (very Leonard). Serge, because he was writing the song for Jane to sing, dropped his typical defence of biting cynicism and arch wit, and instead bared his soul—through a silk stocking, darkly. Indeed, the alliance of masculine pain and feminine frivolity, of a broken heart and a laddered stocking, is a poetic conceit that works brilliantly, neither belittling the woman nor aggrandizing the man. Very Cohenesque.

1 – Jane Birkin quoted in Vogue from the Archive, 16 July 2023

2 – Jane Birkin quoted in Gilles Verlant, Gainsbourg (Paris: Albin Michel, 2000) p. 591

Vogue photo: Peter Lindbergh

If ‘Les dessous chics’ were only ‘about’ Serge’s pain at having being abandoned by his long-time lover, Jane, it would be just one more exquisitely crafted song about the end of a love affair. What elevates it to greater heights is the way it embodies the notions of ‘pudeur’ and ‘manners’. ‘Pudeur’ is usually translated as ‘modesty’; the French word, however, is far richer than that English rendering. Indeed, ‘modesty’ has a negative valence, especially in an America that believes the ego is master in its own house: ‘reserve’, ‘shyness’, ‘timidity’ (very un-American) seem to lurk behind the word. ‘Pudeur’, in contrast, has a positive valence; it refers to the safeguarding of a domain of privacy wherein the self makes no concession to the social. Understood thus, the pudique person has a certain sophistication. He/she understands the limits of language and the hindrances of habit; he/she embodies presence and inhabits silence in a way that is more eloquent than speech. In words and music, this pudeur is what Serge conveys in this poetic jewel of lyrical concision.

Vogue photo: Will Vanderperre

As for manners, they derive from the understanding that the opposite of stupidity is not intelligence, but humility. Aware of all that exceeds our rational comprehension, the well-mannered person has certain rituals of style that enable him/her to attain a state of grace. In ‘Les dessous chics’, Serge’s manners consist in inserting a veil between his pain and its expression, a veil that in one and the same evocation conjures up past pleasures and present tribulations: ‘C’est une jarretelle qui claque / Dans la tête comme une paire de claques’; ‘C’est des dentelles et des rubans / D’amertume sur un paravent’. The final verse—’Ce serait comme un talon aiguille / Qui transpercerait le cœur des filles’—I interpret as an appeal to les filles to turn their stilettos of seduction into weapons of self-destruction: to obliterate, in an act of ritual suicide, the unbearable lightness of the floating world. ‘Iodine’ may well be Leonard Cohen’s most Gainsbourgien song; ‘Les dessous chics’ is certainly Serge Gainsbourg’s most Cohenesque one.

Vogue photo: Craig McDean

2. LIGHT AS THE BREEZE | GLASS SECURIT

LIGHT AS THE BREEZE

Leonard Cohen

She stands before you naked

You can see it, you can taste it

And she comes to you light as the breeze

Now you can drink it or you can nurse it

It don’t matter how you worship

As long as you’re down on your knees

So I knelt there at the delta

At the alpha and the omega

At the cradle of the river and the seas

And like a blessing come from heaven

For something like a second

I was healed and my heart was at ease

O baby I waited

So long for your kiss

For something to happen

Oh something like this

And you’re weak and you’re harmless

And you’re sleeping in your harness

And the wind going wild in the trees,

And it ain’t exactly prison

But you’ll never be forgiven

For whatever you’ve done with the keys

O baby I waited

So long for your kiss

For something to happen

Oh something like this

It’s dark now and it’s snowing

O my love I must be going

The river has started to freeze

And I’m sick of pretending

I’m broken from bending

I’ve lived too long on my knees

Then she dances so graceful

And your heart’s hard and hateful

And she’s naked but that’s just a tease

And you turn in disgust

From your hatred and from your love

And she comes to you light as the breeze

O baby I waited

So long for your kiss

For something to happen

Oh something like this

There’s blood on every bracelet

You can see it, you can taste it

And it’s please baby, please baby please

And she says, drink deeply, pilgrim

But don’t forget there’s still a woman

Beneath this resplendent chemise

So I knelt there at the delta

At the alpha and the omega

I knelt there like one who believes

And the blessings come from heaven

And for something like a second

I’m cured and my heart is at ease

GLASS SECURIT

Serge Gainsbourg

Tequila aquavit / Un glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

À jeun je trouve ça limite

J’ai besoin d’une bit

Ure bien composite

Tequila aquavit / Un glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

Tequila aquavit

Je recherche Aphrodite

Froideur explicite

Ouais j’y vais sans hésit

Ation mais pas d’excit

Ation climax exit

Tequila aquavit / Un glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

Tequila aquavit

Que de langues sodomites

De doigts troglodytes

Des plombes que je te visite

Absence de coït

Okay on est quitte

Tequila aquavit / Un glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

Tequila aquavit

Toi tu l’prends comme un rit

Uel un plan habit

Uel plus rien ne t’excite

À jeun je trouve ça limite

J’ai besoin d’une bit

Ure bien composite

Tequila aquavit / Un glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

Tequila aquavit

Mon verre securit

Éclate en petites

Particules j’évite

De les mettre en orbite

Sur ta chrysalide

Tequila aquavit / Plus de glass securit / Pour prendre ton clit

Tequila aquavit

Je ne sais ce que nécessitent

Ton con et ton clit

Je suis perdu j’hésite

Oh et puis merde je quitte

Tes muqueuses shit

Tequila aquavit

J’ouvre mon lexique

Mallarmé dixit

Je cite

Tequila aquavit

Et dans ses jambes où la victime se couche

Levant une peau noire ouverte sous le crin

S’avance le palais de cette étrange bouche

Pâle et rose comme un coquillage marin

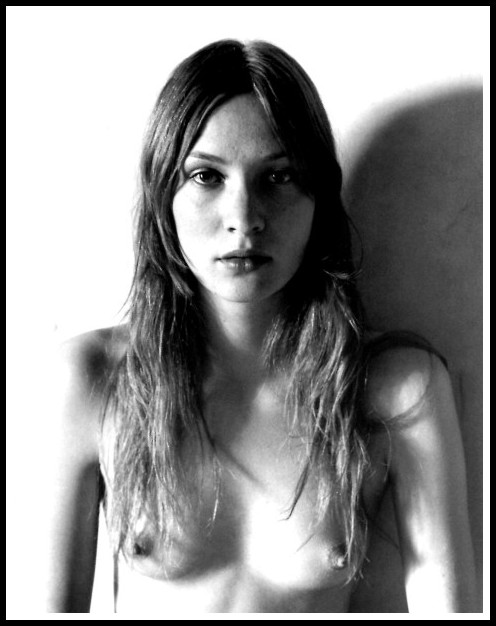

Bettina Rheims, Dolores with her husband François, 1988

Sylvie Simmons: When Leonard in his twenties in The Favourite Game recreated the episode [of putting the family maid in a trance and instructing her to undress], he wrote, ‘He had never seen a woman so naked. He was astonished, happy, and frightened before all the spiritual authorities of the universe. Then he sat back to stare. This is what he had waited for so long to see. He wasn’t disappointed and never has been.’ Although it is ascribed to his fictionalized alter ego, it is hard to imagine that these sentiments were not Leonard’s own. Decades later he would still say, ‘I don’t think a man ever gets over that first sight of the naked woman. I think that’s Eve standing over him, that’s the morning and the dew on the skin. And I think that’s the major content of every man’s imagination. All the sad adventures in pornography and love and song are just steps on the path towards that holy vision.’ The maid, incidentally, was a ukulele player, an instrument his fictional alter ego took for a lute and the girl, by extension, for an angel. And everybody knows that naked angels possess a portal to the divine.1

In ‘Light as the Breeze’, on the healing power of cunnilingus, the sweetness is tempered by a sense that the comfort of sex and love is fleeting, little more than a Band-Aid to get you back into the ring for another round.2

1 – Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 20

2 – Ibid., p. 369

Elle photo: Chico Bialas

It is instructive to compare the poem ‘Celebration’, Leonard Cohen’s commemoration of an act of fellatio, with ‘Light as the Breeze’, the song in which he celebrates an act of cunnilingus. The poem was published in The Spice-Box of Earth in 1961 when Leonard was 27; the song appears on The Future, an album released in 1992 when Leonard was 58. The poem is as limpid as a mountain stream in spring; its evocations of history (dancing Roman girls) and mythology (Samson pulling down the Temple) are seamlessly integrated into the account: to experience the poem’s fluidity, simply read it out loud. Sensuous and joyous, with just the right measure of solemnity to convey the performance of a ceremony, the poem moves from abstract time to an unfolding present that, paradoxically, the historical and mythological allusions only reinforce. In and of the present, the poem is now. It is, clearly, the work of a young man.

CELEBRATION

Leonard Cohen

When you kneel below me

and in both your hands,

hold my manhood like a sceptre,

When you wrap your tongue

about the amber jewel

and urge my blessing,

I understand those Roman girls

who danced around a shaft of stone

and kissed it till the stone was warm.

Kneel, love, a thousand feet below me,

so far I can barely see your mouth and hands

perform the ceremony,

Kneel till I topple to your back

with a groan, like those gods on the roof

that Samson pulled down.

Vogue photo: Steven Klein

‘Light as the Breeze’, in contrast, is autumnal in character, with winter fast approaching: it is the work of an old(er) man. In it, the act of cunnilingus is freighted with the residue of years of relationship. The purity of the act can be isolated, but only for ‘something like a second’: the limpid stream in now a murky river, and it is the woman—even as she offers her oyster to the man to savour—who is making it so: ‘And she says, drink deeply, pilgrim / But don’t forget there’s still a woman / Beneath this resplendent chemise’. What was once simple is now difficult; what was once carefree is now of concern. In ‘Light as the Breeze’, then, the act of cunnilingus offers a respite from relationship, a moment in which the lover can forget ‘there’s blood on every bracelet’. But only for a moment: the woman, during the act, may be ‘as light as the breeze’, but the man is ‘as heavy as the sand of the sea’.1 Why? Because as long as the pilgrim has paused, the blood (on the bracelet) will sting like iodine. So, is ‘Light as the Breeze’, like ‘Iodine’, another sad song? Yes, if by ‘sad’ we mean the kind of emotion conveyed in Lou Reed’s ‘Sad Song’.2

1 – Adapted from Job 6:3

2 – On Berlin and Lou Reed Live.

Vogue photo: William Garrett

Like Leonard Cohen, Serge Gainsbourg has a fellatio counterpart to his cunnilingus song. His ‘Suck Baby Suck’, however, is devoid of poetry, and as such is the antithesis of ‘Celebration’. Indeed, his lyric comes across as that of an impotent drunk with one foot in the grave, fantasizing in a final jerk-off before he gives up the ghost.1 If ‘Suck Baby Suck’ is more pathetic than sad, ‘Glass Securit’ is sadder than sad. Both songs are from You’re Under Arrest, an album with a narrative line that Serge summarizes thus:

I fuck a 13-year-old black girl, I corrupt a minor. Now, a 15-year-old, that’s corrupting a minor—a girl of 13, that’s what you call rape! That’s how I wanted it. She’s a heroin addict, and since that’s not my bag, I dump her and beat it, join the Foreign Legion.2

Blind to the pathos of his position, he unwittingly articulates his desperation: incapable of feeling, he chases sensation, like a dog chasing its tail. Three terms suffice to capture the impetus of the lyric. Overkill: black, thirteen, heroin addict. Beating a dead horse: taking his limp cock for hard rock, he takes a gelding for a stud. Delusions of grandeur: Georgie Porgie, pudding and pie / Kissed the girls and made them cry / When the girls came out to play / Georgie Porgie ran away.

1 – I’m being unfair here, for we must not forget that Serge is playing a character in a story: it is the way he delivers the other songs from the album during the Zénith 1989 concert (available on DVD) that justifies my characterization.

2 – Serge Gainsbourg interview in Rock & Folk magazine, Dec. 1987. Cited in Pierre Mikailoff, Gainsbourg confidentiel (Paris: Éditions Prisma, 2016. Kindle edition). Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Helmut Newton, Raquel Welsh, 1981

In ‘Glass Securit’, in contrast, the lyric is excellent: the constraint of the relentless rhyme in ‘it’ offers a freedom that widens semantic horizons. Serge’s tripartite marriage of Otto Dix and George Grosz with the rhythm of the Bronx and the rigor of symbolist poetry is, despite his state, magisterial. Leonard never resorts to such ‘overly-refined’, ‘artificial’ prosody; instead, in the poetry, he makes of free verse a vehicle for the intimacy of his voice, and in the lyrics, his prosody comes across as conversational. As for diction, we note Serge’s anatomically precise ‘clit’, in contrast to Leonard’s metaphorically general ‘delta’. Leonard’s imagery, too, is more ‘conventional’ than Serge’s: ‘at the delta, at the alpha and the omega’, ‘light as the breeze’, ‘the cradle of the river and the seas’, ‘the wind going wild in the trees’, ‘the river has started to freeze’ to Serge’s ‘tequila aquavit’, ‘un glass securit’, ‘de langues sodomites’, ‘de doigts troglodytes’, ‘sur ta chrysalide’. One could say Leonard makes the most of simplicity, while Serge resorts to exoticism; or, simply, that Serge is more recherché than Leonard. Here, his citation of Mallarmé is only the most obvious instance of this.

Jean-Baptiste Mondino, Sharon Stone, 2008

Serge Gainsbourg’s ‘Glass Securit’ would not be entirely out of place in Leonard Cohen’s The Energy of Slaves,1 his 1972 collection of poems. In # 4 from that volume we read:

My own music

is not merely naked

It is open-legged

It is like a cunt

and like a cunt

must needs be houseproud

And in # 54:

I could grow to love

the fucking in New York

far from the soil

but dreamy and courageous

And in # 81:

Why did you spend

another night with her

when you could have slept

with Naked Jane

or bought yourself

a twelve-year oriental girl

Why don’t they make Vietnam

worth fighting for

1 – Leonard Cohen, The Energy of Slaves (London: Jonathan Cape, 1972) pages 12, 63, 91

Helmut Newton, Celia, Miami 1991

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments