STRINDBERG – MISS JULIE – A SEQUENCE-BY-SEQUENCE ANALYSIS (2/2) – JESSICA CHASTAIN – SAFFRON BURROWS

MISS JULIE: DRAMA OF THE SEXES – PART 5 – TWO FILM VERSIONS

MIKE FIGGIS & LIV ULLMANN – MISS JULIE – A CRITICAL COMPARISON – 3/3

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

THIS ESSAY IS SPLIT INTO 3 POSTS. TO READ 1/3, CLICK: CRITICAL COMPARISON 1 OF 3

Saffron Burrows | Jessica Chastain

IX. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 9

Julie alone, immediately after the fuck

LIV ULLMANN

The emblematic moment in this sequence occurs when Julie, having just left Jean’s room and he Kathleen’s, walks past him without acknowledging his presence. She looks more like a woman who’s just left an operating table rather than a lover’s bed.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain & Colin Farrell

This is consistent with Liv Ullmann’s interpretation of the Julie-Jean relationship: an encounter between asexuals. Not only is Julie an Eve who has not bitten the apple, she’s never even seen the serpent, so uncomprehending is she of the sex act. There is no pathos in this bewilderment, only incredulity that a director could ask a 36-year old actress to play such ignorance—there’s nary a pubescent girl who doesn’t know that a place of magic lies between her legs.1 Ullmann even has Julie hide, like a little girl, the undergarment with which she’d wiped her groin.

1 – Diametrically opposed to Ullmann’s characterization, Strindberg’s Julie is a woman aware of her sexuality. Two phrases she utters suffice to make this clear: ‘my womb cried out for your sperm’ (Ullmann’s translation) and ‘it [our fuck] could happen again’ (tellingly, Ullmann leaves this line out, for it contradicts her asexual take on Julie’s desire).

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

This scene also has Jean continue the sideshow with Kathleen. The cook’s increased weight in the film drains it of Strindberg’s aspiration to tragedy: it now flounders in melodrama. Ullmann has Kathleen mirror Julie in a different mode: where Julie floats on a cloud of unknowing, Kathleen’s bewilderment adopts an earth-bound stance. The one is as inappropriate as the other: the mistress of the kitchen necessarily has a certain smarts, while the Count’s daughter is anything but an airhead. If there’s a self-consistency in Ullmann’s directorial choices, it doesn’t make her interpretation any less counter-productive. Indeed, her attempt to ‘correct’ Strindberg sabotages the drama: it is now an empty shell.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

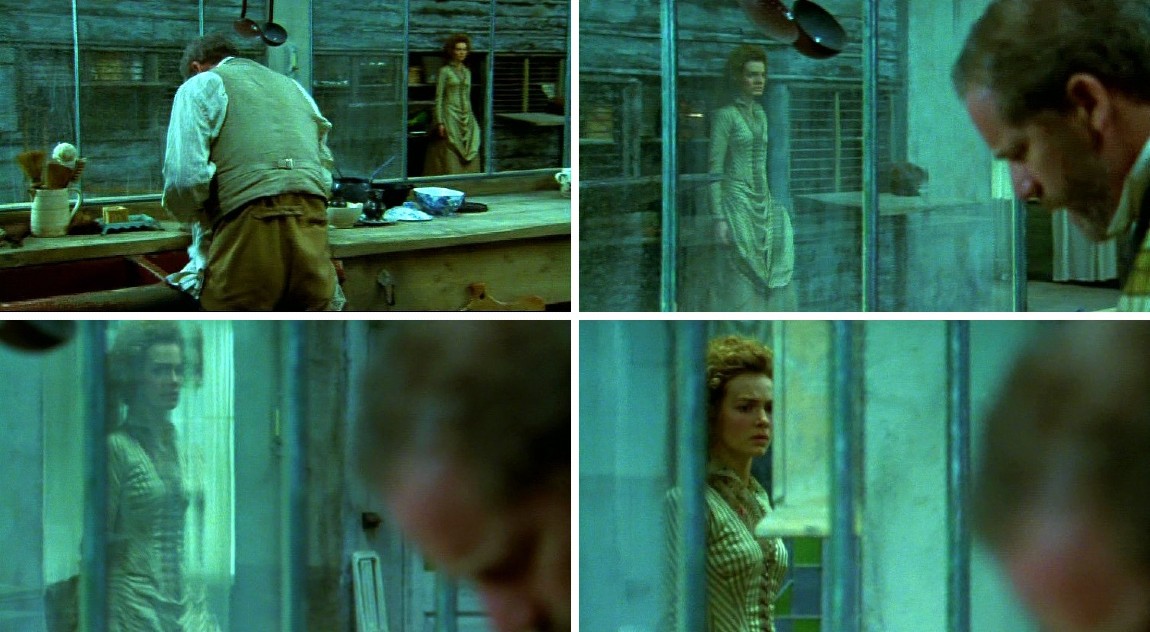

This sequence consists in a single shot, simply choreographed and highly effective. It begins with the camera tracking in at an oblique angle to Jean washing his cock at the kitchen sink. Back to us, busy with his ablutions, he stands in long shot in the left of the frame, while Julie, standing outside the storage/pantry area where the fuck took place, is viewed through a glass-pane screen in the right of the frame. The camera, now right beside Jean, views him in profile, in close-up, while Julie, still in long shot, slowly approaches the opening in the glass screen and steps, now in mid-shot, towards the kitchen proper. Just before she reaches the doorway, we view her distorted image in a thick pane of translucent glass. Because the choreography is so organic, so germane to the drama, the effect is not gimmicky but highly evocative.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

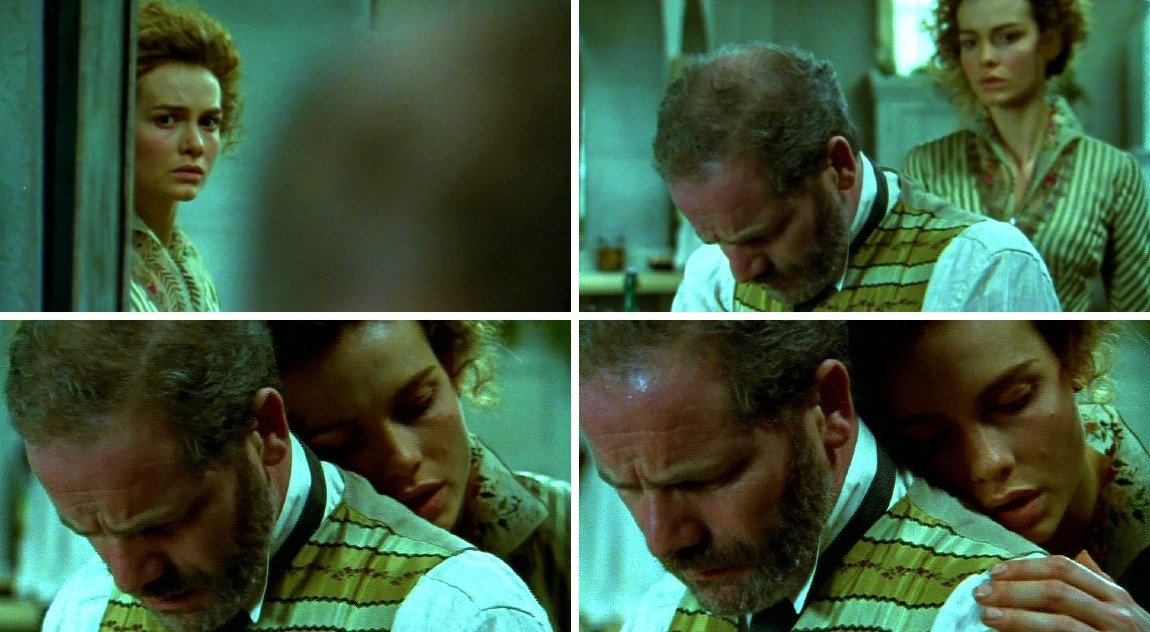

Julie then steps through the doorway and pauses, looking intently at Jean, now viewed in a tight close-up. She then approaches him from behind and, in mid-close-up, rests her head against his upper back. The scene is transcendent, because it rings so true to life: this is how a woman who has just been fucked, a woman who takes her share of responsibility for the incident itself and the disquiet surrounding it, would behave. ‘Say my name, say Julie. There are no barriers between us now’, she tells him. Julie’s embrace of Jean bodily acknowledges the momentousness of the fuck. ‘Yes’, her gesture seems to be saying, ‘my world has been turned upside down, but I too have changed’. This instant of recognition, regardless of its subsequent evolution, rings true. The sequence, at once so simple and so complex, so throw-away and so profound, will now launch the film towards its dénouement.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

X. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 10

Jean & Julie – I’ll start a hotel

LIV ULLMANN

We are now out of Strindberg’s world and in Liv Ullmann’s. The director has long been a fan of Tennessee Williams,1 and now she has Jessica Chastain intensify a Method style that harks back to Williams’ heyday. What does she ask of the actress? That she play a violated virgin, as ignorant as she is innocent, one push away from a nervous breakdown. As for Colin Farrell, Ullmann is content to keep him stuck in the groove she’s placed him in, a broken record of apologetic whining. If ‘a mind is a terrible thing to waste’, so is acting talent. Recapitulation: Liv Ullmann insists on ‘correcting’ Strindberg by adding ‘explanatory’ dialogue. On her cinematic scales the verbal far outweighs the visual, suggesting that she lacks confidence in her filmmaking skills: she always opts to ‘tell’ (verbally) rather than to ‘show’ (cinematically). And if that weren’t bad enough, she also has no confidence in the audience’s ability to put two and two together: she keeps telling them, ‘four’, ‘four’, ‘four’. Moving on: We have seen these problems in earlier sequences, but now they are fatal, for Strindberg’s drama has been eviscerated: Ullmann has scooped the guts out of Julie, leaving her saying lines that now ring hollow, and, having emasculated Jean, she has left him a whimpering whiner, ‘beweeping his outcast state’. I’ll say it again: the ‘war of the sexes’ is an ontological conflict, not a misunderstanding that can be resolved by ‘listening’. In refusing to accept this premise of Strindberg’s play, Ullmann gives us a melodrama of mediocrities, not a work that aspires to tragedy.

1 – See, for example, her Lincoln Center interview

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

A world without conflict between men and women may be Liv Ullmann’s idea of heaven, but, as Talking Heads remind us, ‘heaven is a place where nothing ever happens’.1 Samuel Beckett wrote a play in which ‘nothing happens, twice.’2 The status of art this work attains is due precisely to Beckett’s understanding that, existentially, listening solves nothing. Had Liv taken more from Sam and less from an actress’ feeling for a certain Tennessee, her Miss Julie might have had a chance at attaining the status of art too. Sartre, in Huit Clos, took us to hell. Strindberg’s cycle of sex-war plays gives us a tour of hell-on-earth. As for Liv Ullmann, her artistic sensibility, as we saw in Miss Julie Drama of the Sexes Part 3, is attuned neither to hell nor to hell-on-earth: ‘In some ways, acting for Bergman has been difficult, because I am not that dark. I really am not, and maybe I would have liked to do more life-affirming stuff.’3 In trying to contort Strindberg’s play into a ‘life-affirming’ movie, she has only succeeded in leaving us in limbo. In trying to tell us how to get to heaven—listen to each other—she has left us longing for hell. Why? Toss a coin. Heads: The earnestness of bons sentiments is boring—compare Godard’s free-thinking films to his politico-didactic ones. Tails: Hell is more exciting—compare Dante’s Inferno with his Paradiso. Recall this extract from an interview with Christian Schiaretti, director of the Théâtre National Populaire in Paris, that I cited in Miss Julie Drama of the Sexes Part 3:

Strindberg is a dramatist who is more ‘disruptive’ than both Ibsen and Chekhov. Ibsen is aligned with the flow of history, while Chekhov gives us an ‘impressionistic’ history full of precautions (the relativity of truth, the plurality of interpretations). Strindberg, for his part, ‘knifes his way forward’. He seeks the tragic, and thus he seeks ontological antagonism, however ‘politically incorrect’ it may be. His ‘political incorrectness’ can be seen not only in the way he talks about women, but also in the way he shows men’s weaknesses, their abysmal mediocrity. This, along with his vision of impending darkness and of the permanence of the structural rivalry between men and women, explain why, unlike Ibsen, he will never fit into the boxes of the politically correct and, unlike Chekhov, he will never fit into the mould of those who hedge their bets.4

Liv Ullmann, in trying to ‘fit Strindberg into the box of the politically correct’ while ‘hedging her bets’ by not ‘correcting’ everything, has given us a Miss Julie, or the Consequences of Not Listening that aspires to feminist fireworks, but ends up a damp squib.

1 – David Byrne & Jerry Harrison, ‘Heaven’. Talking Heads, Fear of Music (Sire Records, 1979)

2 – Waiting for Godot

3 – Liv Ullmann, interview in the bonus to the DVD of Faithless, a film she directed from an Ingmar Bergman script (UK: Tartan DVD, 2001)

4 – Christian Schiaretti, interview on the DVD of his production of Mademoiselle Julie (Théâtre National Populaire), Collection COPAT/CNC, 2012. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

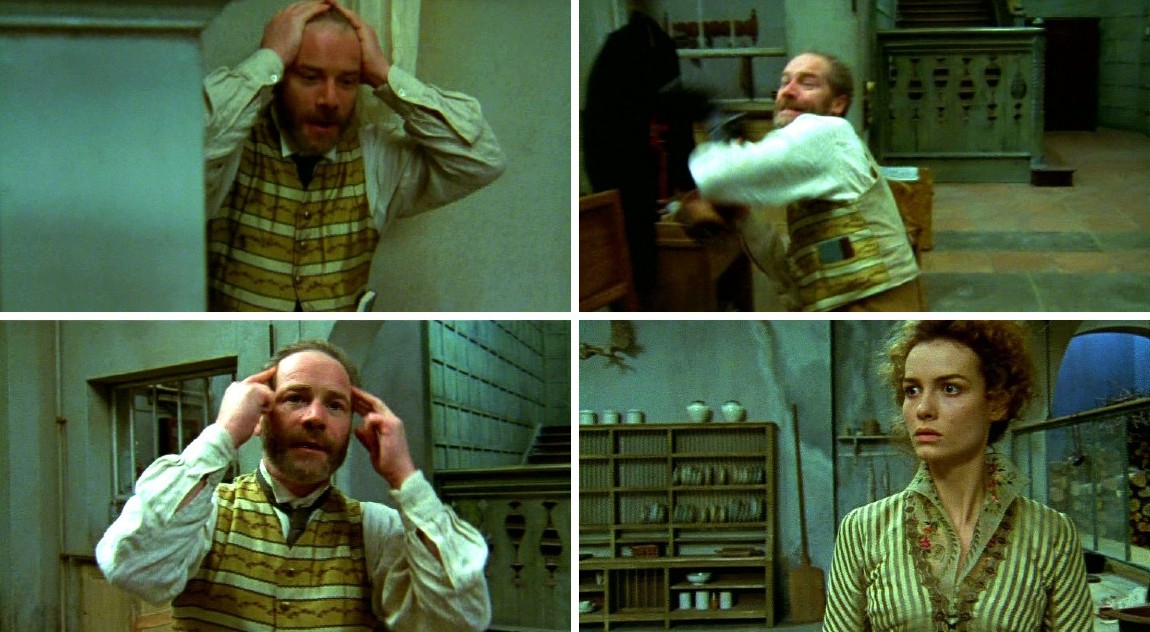

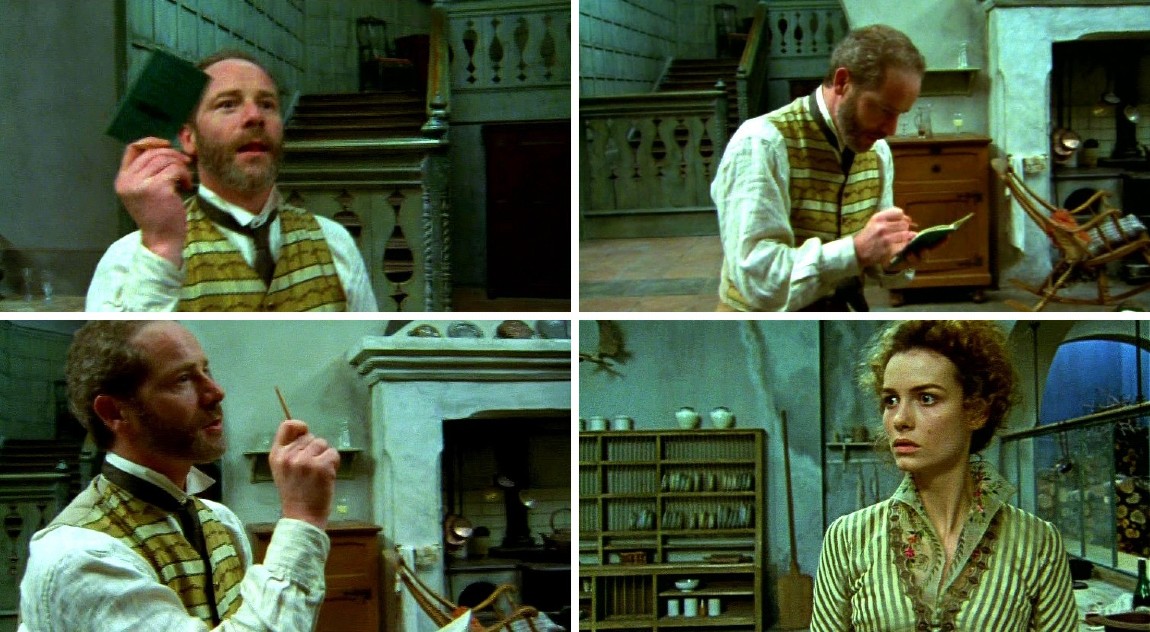

This sequence deepens the contrast in mise-en-scène and direction of actors between Figgis and Ullmann. By over-egging the pudding in her rewriting of Strindberg, Ullmann ended up with an overwritten film script. Bad enough, but she made things worse by having her actors set their ‘emote’ button to maximum. Figgis did the exact opposite. He presented his actors with a stripped-down script and had them adopt an understated stance in their acting. The effect of the contrast between the meticulously low-key acting and Strindberg’s viciously high-strung text is stunning. Picking up from the previous sequence—‘Say my name. Say Julie. There are no barriers between us now’—Saffron Burrows’ seductive hush could be pillow talk, and it leaves no doubt about Julie and Jean’s complicity. Against this ground Jean’s violence now figures a dramatic contrast: ‘Not here. Not in this house.’ Having broken out of Julie’s embrace, he says this from the opposite end of the kitchen. ‘I respect this man.’ Beside himself, he then hurls the Count’s boots across the room. Peter Mullan’s acting is excellent, for it is multi-dimensional: he is overwhelmed by the turn of events, he is lucid about his situation, and he is determined to get a grip and move on. Julie watches him bewildered, yet there is dignity in her anxiety. At once partners in crime and outright antagonists, Julie’s and Jean’s ambivalence makes for a muscular drama between well-matched protagonists. Where Ullmann conducts a shouting match, Figgis orchestrates a war of the sexes. Refusing victimhood, his Julie and Jean never lose their pride and pluck.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Peter Mullan & Saffron Burrows

In Figgis, dialogue emerges organically out of the dramatic situation and is seamlessly integrated with bodily expression. Take Jean’s ‘let’s go abroad’ speech: standing some distance from Julie, he insistently taps his pencil on his notebook. In that gesture, the ardour of optimism vies with the energy of desperation, the impetuosity of confidence with the debilitation of doubt. Filmed in close-ups in ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging’, this is naturalistic cinematic acting at its finest. Figgis now has Julie continue in her mode of stunned wonder, offering a striking contrast to Jeans’ naturalism. Indeed, when he finishes his speech, she simply says, ‘Say you love me’. The disjuncture between Jean and Julie is made evident at least as much in how they speak as in what they say. Dramatically, this works brilliantly. It is one more example of how Figgis’ direction of actors produces far more interesting results than Ullmann’s.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Peter Mullan & Saffron Burrows

A word about the actors. Peter Mullan brings a rough-hewn masculinity and a school-of-hard-knocks authority to Jean that compensates for his being too old (forty) and too short (compared to Burrows) for the role. As for Julie, the film depends on the precise casting of its (anti-)heroine: if she is miscast, irrespective of how good the actress may be, the film will fail. In casting Julie Figgis chose wisely, for Saffron Burrows, aristocratic in stature and easy in elegance, astutely blends daring and doom to offer a compelling Julie. She’s equally at ease in a full-length gown as in her own skin, generating a sexiness that derives from her self-astonishment as she inhabits her body with boldness and vulnerability. Trusting her instincts and her understanding, she finds in herself what the moment demands. Here, she plays Julie with restraint and truthfulness, sensitivity and panache. And because Mike Figgis often has her speak softly and slowly, in frames less mobile than before, the dark timbre of her voice resonates, in counterpoint with the subtext of the scene, to great effect. The director-actress collaboration here attains a standard I’ve not seen since Fassbinder-Schygulla.1

1 – I’d have said Fassbinder-Carstensen, but Burrows is more like Schygulla in that both are untrained, instinctive actresses. Jessica Chastain is more like Margit Carstensen, but, never having had a role as challenging as the roles Fassbinder wrote for Carstensen, she hasn’t yet been able to express the fullness of her talent. As Chastain herself has said, ‘Hollywood is not only unimaginative but anti-imaginative, particularly when it comes to female actors’ (The Guardian, 10 Dec 2022)

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

In the next section of the sequence, Julie and Jean first play a game of verbal chess, as it were, facing each other from either end of the long kitchen table. ‘Do you really think I can stay under this roof as your whore, with those people pointing their greasy fingers at me?’ In drawn-out undertones, deliberately and decisively, Julie makes her moves. Scooping up a pawn, she says ‘You bastard’ in response to Jean’s ‘It was a story for women’.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The duel then mutates from chess game to boxing match as, in response to Julie’s ‘Servant. Footman. Stand up when I speak to you’, Jean walks over to Julie, grabs her by the jaw and, squeezing her cheeks, says, ‘Servant’s slut. Footman’s whore. Why don’t you shut your mouth and fucking get out of here!’.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

As Jean follows this uppercut with a left hook, Julie simply stops defending and lays herself open to further punches: ‘Hit me. Trample on me, I’m worthless… Why don’t you hit me?’ After pugilism’s artful violence and the cold calculation of chess, comes the gentler game of checkers. Jean: I could never make you love me. Julie: How can you be sure of that? Jean: But I could love you.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The sequence ends with a quick reprise of the three battle modes. Boxing-Julie: You are lower than a sewer rat. I loathe you, I loathe you, I loathe you. Chess-Jean: There is money in there. Take the money, and bring it down here. Checkers-Julie: Give me a glass of wine. It is this modulation from one mode to another, like the control of pacing by a long-distance runner, that keeps Figgis’ film spellbinding. On stage or screen Miss Julie, I’d be willing to bet, has never been better served.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The final section of the sequence—Julie, seated at the table in a throne-like armchair, Jean standing beside her as she drinks—confirms Figgis’ interpretation of Julie as not only sexually aware but also sexually experienced. Two moments make this clear. The first is this exchange: Jean: You hate men, don’t you? Julie: Yes, most of the time. But then sometimes when I’m weak… Oh, my God! Figgis’ Julie has the gift of lust. Given the circumstances of her life, it is not surprising that this gift finds expression in fantasies of violence: Jean: You hate me, don’t you? Julie: Utterly. I’d like to have you slaughtered.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The second occurs in the following speech, when Julie casts a glance at Jean’s crotch when she delivers the line ‘And there, we enjoy each other’: ‘We escape to Lake Como where the sun always shines and the laurels are green at Christmas time and the oranges glow. And there, we enjoy each other. For ten days, eight days, however long it lasts. And then we die.’ In mythological terms, if Ullmann’s Julie is the Virgin Mary, not knowing what has befallen her till Gabriel flies in to inform her, Figgis’ Julie is Mary Magdalene, she of seven demons possessed, she in whom sin and sexuality coincide. If the interpretation works so well, it is largely because Saffron Burrows radiates both the sensuality of her own youth and the bridled sexuality of Julie. Again, in contrast to the lack of contradiction in Ullmann’s film, we see how, in Figgis’ dialectical approach, a stimulating turbulence arises when one current intersects with another of contrary flow.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

XI. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 11

Jean & Kristin – Shame on you! What an evil thing to do!

LIV ULLMANN

Samantha Morton was not interested in playing Kristin as Strindberg wrote her, so Liv Ullmann rewrote the role to satisfy the actress.1 Insofar as it destroys the dynamics of Strindberg’s drama, the result is a disaster. Indeed, this sequence, set by Ullmann in Kathleen’s room, sees John’s whining and whimpering reaching new lows. As Julie, too, has been reduced—despite a magnificent outburst of anger—to a whimpering whiner, Strindberg’s war of the sexes is now a pillow fight between feather-weights. If a great actress does not necessarily a great writer-director make, then that writer-director might not have gone so astray had she had the humility to respect Strindberg’s dramatic genius, however antithetical she found it to her philosophy of ‘listening’.

1 – Fräulein Julie DVD, bonus (Alamode Film Distribution – Alive, 2015). Moralistic Kathleen, so stuck-up as to be outraged, I imagine, by Mary Magdalene’s anointing of the corpse of Christ—’Class is class! A two-bit whore and the Son of God!’—dominates this sideshow called The Cook, Her Dog, the Footman and His Lover: A Cautionary Tale for Those Who Shall Inherit the Earth, Told by a Believer in Listening.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

Where Ullmann never ventures beyond her narrow range of vocabulary and syntax, limited to the basic shots and cuts of elementary filmmaking, Figgis employs ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’ to articulate space in all its dimensions, making his dramatic points through cinematography and editing, not just acting. For example, when Christine asks Jean, ‘What’s been going on?’, the camera obliquely lines up Christine standing in the foreground, Jean seated in the mid-ground, and the Count’s coat and hat on their stand in the background. The diagonal, by making it difficult to anticipate what will come next, creates dramatic tension. The camera then zooms into a medium shot of Jean as Christine crosses the frame. By such means Figgis manages the build-up and release of tension, until Jean finally confesses–wordlessly, via a look alone—that he did indeed fuck Julie. A musician, Figgis knows all about discord and resolution, and here he ‘stages’ the ‘melodic line’ (sex) while bringing in counterpoint (class) and harmony (the sex lives of the kitchen girls and of the Jean-Christine couple) and rhythm (optimizing the impact of each dramatic point). Dynamic and polyphonic, this is cinematography exploiting its potential and editing ‘transforming chance into destiny’.1

1 – Jean-Luc Godard, ‘Montage my Fine Care’. In Godard on Godard, tr. & ed. Tom Milne (NY: Da Capo Press, 1972) p. 39

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

Figgis also stages dialogue far better than Ullmann. The spectator feels at once like a fly on a wall, overhearing natural speech, and like an interpreter of what’s being said and done, his eye and the camera’s being one. The next section of this sequence illustrates this well. The camera is at eye level at one end of the table and Jean is seated at the other, the wide-angle lens making him seem far away—which, of course, he is, in that his thoughts are with Julie and how to surreptitiously get her out of the house. In the foreground we see a glass of wine on the table, reminding us this morning of the night before. To the right, at some distance from Jean, Christine stands preparing a dog’s breakfast (a fine comment, if one gets it, on Jean and Julie’s situation). The banter between Christine and Jean is apparently banal, but Christine quickly homes in on what Jean and Julie have been doing. When she asks, ‘Were you drinking with her as well?’, we cut to a reverse shot, over Jean’s shoulder and at his eye level, while in the silence that Jean keeps, Christine moves towards him as the camera tracks to frame her frontally, leaving Jean in a close-up profile. ‘Look at me’, she demands. The camera cuts to an over-the-shoulder shot of her looking down at him, his head still seen in profile. When he finally does turn to look up at her, the effect is scintillating: it encapsulates the gist of the sequence in one image, an image of power and humiliation, of dignity and disgrace, and all the ambivalence that attends these states. Once again, we see how Figgis is telling the story cinematically: were one to silence the sound, we would still understand what’s happening. He shows us here just how effective simplicity can be, a simplicity arrived at through careful choreography. Where Ullmann passively accepts the default conventions of space and time, Figgis actively manipulates space and time to serve the drama. Where she gives us a recording of actors performing, he gives us a total cinematic experience.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

XII. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 12

Jean – Tidies the kitchen. Gets his belongings. Packs his suitcase.

LIV ULLMANN

This brief transitional sequence begins with an overhead shot of John scrambling to tidy up the kitchen. In the second shot we see Kathleen from behind in long shot, standing in a field with the dog, the wind fluttering her skirt. The third shot is of Julie sitting on her bed, cradling her birdcage in her arms. The curtains, filtering the daylight through their red translucence, are closed. In the final shot we see John leaning anxiously against the kitchen door, taking off his tie. In cinematic terms the sequence as a whole certainly works—it’s the calm before the storm, a breather before the blowup—and it is consistent with Ullmann’s aesthetic choices. One of these choices is ‘illustrate as much as possible’. Shot 3 is a prime example of this. It can read as a set of three Russian dolls. The outer one, the bedroom bathed in crimson light, is the womb of the Count’s wife: Julie has regressed to a uterine existence; she is a baby—one wouldn’t be surprised to see her sucking her thumb. The middle doll is Julie cradling her birdcage, the bird being a stand-in for Julie herself: she is, in effect, engaged in an act of self-soothing, she is hugging herself. The inner doll is Julie’s womb and John’ semen is inside it. Does Julie have a post-coital afterglow? No, for she is sexless, and as such, ‘unacquainted with evil’ (an Eve who’s never bitten the apple). If she can’t be a whore, can she be a mother? Yes, but only to herself, for she cannot handle alterity, be it in the form of lover or baby. And thus Ullmann persists in her portrayal of Julie as violated virgin, incapable of doing what all of us, no matter what our circumstances, are called upon to do: ‘to make something of what others have made of us’.1 The director thus forecloses any reading of Julie’s suicide as heroic or even dignified. Had she cut this ‘illustrative’ shot and left the spectator to his imagination, the ending of the film might have regained a bit of what it had (already) lost.

1 – Jean-Paul Sartre

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

Figgis, true to form, opts for dramatic intensity, refusing to dilute the unfolding drama in distracting ‘illustration’. In this he is true to Strindberg’s vision of stripped-down theatre, free of embellishment and subordinate incident. The previous sequence ended with a silent encounter between Jean and the ‘ghost in the machine’: the Count. Indeed, the telephone receiver had been left hanging off the hook; Jean approached it cautiously, picked it up and listened, then hung it up. The present sequence, then, is concretely informed by ‘the ghost of the Count’ (the handling of the telephone as well as the picking up of the boots flung in frustration earlier). In Ullmann’s version, John’s scrambling about the kitchen felt like an inconsequential race against time; in Figgis’, it is different: there is a palpable tension as Jean scurries not to clean up, but to pack his suitcase: Julie’ impending descent from her room intersects with the Count’s impending return, redoubling the dramatic tension. Once again, then, we see how Figgis’ dialectical approach simultaneously moves the plot forward (horizontally) and deepens the drama (vertically) by the co-presence, cinematically, of text and sub-text. The lesson Figgis gives Ullmann parallels the one Mallarmé gave Degas: just as poems are made with words, not ideas, so films are made with things—boots, a telephone, a suitcase—and not bons sentiments.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Peter Mullan

XIII. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 13

Jean & Julie – We can’t take the bird. You should have learned to slaughter properly.

LIV ULLMANN

Here, the filmmaking works fine. It’s Jessica Chastain’s Julie, as conceived by Liv Ullmann, that is problematic. Why? Because she lacks the minimum degree of freedom and responsibility to be a character one can believe in. Contrived, not organic; floating, not grounded, she is an insubstantial self that slips into one stylistic shell after another. That’s perfectly justified, you may think, since Strindberg himself has her say:

I have no self of my own. I haven’t a thought I didn’t get from my father, not an emotion I didn’t get from my mother, and this last idea—that everyone’s equal—I got from him, my fiancé. How can it be my own fault, then? Shift all the blame on to Jesus, as Kristin did?—No, I’m too proud for that, and too intelligent—thanks to my father’s teachings! Whose fault is it?—What’s it matter to us whose fault it is; I’m still the one who’ll have to bear the blame, suffer the consequences.1

This stark speech makes clear the ambivalent nature of Julie’s character. On one hand, she has no thought, emotion or idea of her own; on the other, she has self enough to see that in society’s eyes she must ‘bear the blame, suffer the consequences’. What’s more, she has sufficient pride and intelligence to refuse the convenience of Christ as a scapegoat. Her self, indeed, is capable of assuming her freedom and responsibility.

1 – Strindberg, Miss Julie in Miss Julie and Other Plays, tr. Michael Robinson (Oxford World’s Classics, OUP, 1998) p. 108

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Tellingly, Ullmann left this speech out in her script and replaced it with elaborate ‘explanatory’ dialogue she’d written. Where Figgis, as we shall see, opts to interpret Strindberg existentially, highlighting Julie’s freedom and responsibility, Ullmann opts to interpret him psychologically, highlighting all that ‘excuses’ Julie from freedom and responsibility. The director is not content to underscore the deterministic streak in Strindberg, however, for she casts his psychology in a lyrical-romantic mode that chimes with these politically correct times where no-one is responsible and everything is excusable. In so doing, she does Strindberg a great disservice, because to sentimentalize Miss Julie is to sap the very foundations of the drama. Here’s a sample of the dialogue Ullmann wrote for Julie in this sequence:

On the other side of that wall, I have a place, a secret garden. There’s no wind there. I go there when I’m anxious. I’m anxious all the time. I’m always longing for some other place. You cannot imagine how different I wanted my life to be. When I was little, just after Mama died, I was hoping that all of my garden would be full of animals. They’d come from—I don’t know where they’d come from. They’d be there to keep watch over me. I have a pain in my stomach. I do not know where my sorrow comes from.

Liv Ullmann has Jessica Chastain deliver these lines1 in the arch-earnest register of therapeutic culture where ‘everybody should like everybody’ and ‘listening to each other’ solves everything. To any spectator with a modicum of ‘pride and intelligence’, it is impossible to take such sentiment seriously. Miss Julie is vicious because Strindberg is lucid: to subvert his vision is to sabotage his play.

1 – Such ‘paint-by-numbers’ dialogue, with each phrase bearing the heart of its ‘message’ on its sleeve, is a sign of utter incompetence. If one had expected more from Liv Ullmann, it’s because one has forgotten that a great actress does not necessarily make a great writer.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

Now let’s have look at just how the ‘insubstantial self’ of Ullmann’s Julie ‘slips into one stylistic shell after another’. The sequence begins with a bit of banter between ‘souls on the other side of despair’ (Julie speaks first): The sun’s rising. / And the trolls are dancing. / Yes, they’ve been dancing all night. It then morphs into the mad Ophelia motif that Ullmann introduced at the end of her prologue, with Julie in a trance, lost in a kaleidoscope of images that, one by one, she haltingly evokes:

Please come with me. I can’t go alone, not today. On Midsummer Day, the trains will be packed. I can’t—I can’t go alone in the midst of the black and gray on the train, people looking at me as if they know. / Oh, it’s so beautiful out there. The garden. I never showed you my little brook, did I? I know you’d love it, all my flowers.

The ‘mad Ophelia’ motif, while thematically justified,1 is nevertheless ‘contrived’; it does not arise organically out of Julie’s character (in Ullmann she has none), but is simply a ‘stylistic shell’ into which the director asks the actress to slip (which, be it said in passing, Jessica Chastain does brilliantly).

1 – The following description of Ophelia’s situation suggests certain parallels with Julie’s circumstances: ‘Even in madness, Ophelia is patronized as the ‘pretty lady’ and ‘poor Ophelia’, ‘divided from herself and her fair judgement’. But Ophelia’s ‘self’ and ‘fair judgement’ were never more than a construction of femininity, qua submissive daughter and chaste lover, imposed upon her by the men in the play, Polonius, Laertes, Hamlet and now Claudius. In contrast, madness brings Ophelia briefly but spectacularly to life as a lover and folk-tale heroine. She has started to sing. Insane, Ophelia breaks from the subjection of a vehemently patriarchal society and makes public display, in her verses, of the body she has been taught to suppress. Her speech, once brief and submissive, is now dangerously lyrical, figural and promiscuous. No longer closeted and sewing, passively obedient to the men who owned and subjected her, she roams the palace grounds.’

Duncan Salkeld, Madness and Drama in the Age of Shakespeare (Manchester University Press, 1993) pp. 94-95

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

After the beheading of the bird, Julie discards the ‘mad Ophelia’ shell and slips into that of the Sylvia Plath of ‘Daddy’: in a fit of lucidity she yields to an outpouring of bile. These shifts from one mode of being to another, expressed in varying motifs, are not problematic; the problem lies rather in the fact that outside these borrowed shells, Ullmann’s Julie is an ‘insubstantial self’. As such, her suicide, rather than affirming her freedom and responsibility (she has none) becomes one more stylistic shell, as gratuitous as all the others. This is the fatal flaw in Ullmann’s Miss Julie, and it explains why her film falls so flat. We see, once more, that if a writer will not allow art go where it will, it will go nowhere.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

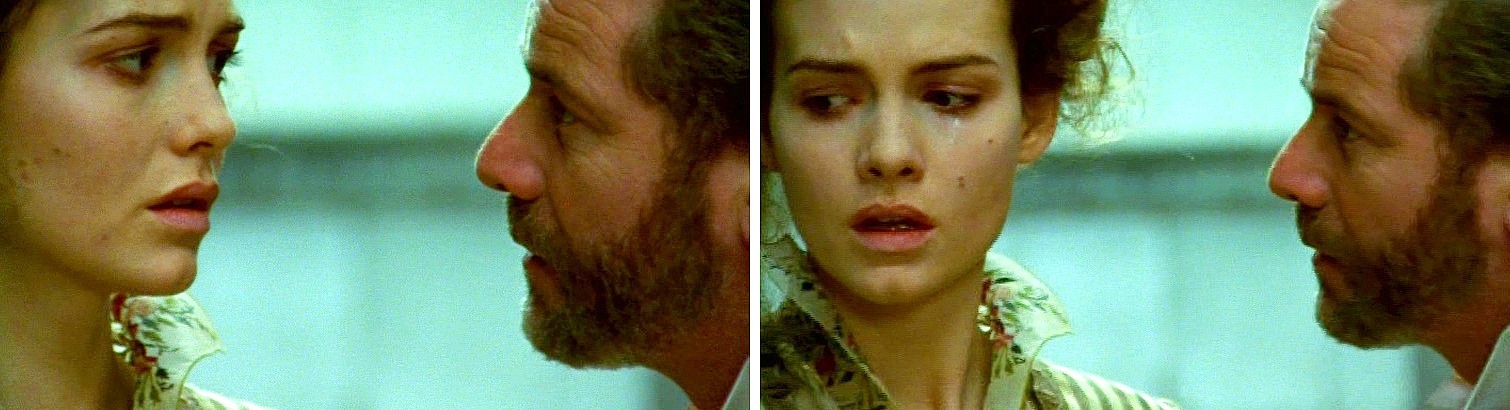

Where Ullmann’s Julie is flighty, floating, and contrived—one sometimes has the impression the actress is trying out different monologues in preparation for an audition—Figgis’ Julie is an organically constructed character, self-assured and purposeful. Her expression is grave as, dressed in the solemnity of liturgical purple, she enters the kitchen. Once again, Saffron Burrows is outstanding in rendering Julie’s shifting states, all arising from the character’s clearly delineated individuality. The first segment is business-like, the dialogue crisp and forthright: In less than twenty words it’s established that Christine does not suspect anything, that Julie’s got the money and Jean can count it, and that the two of them will be leaving together. Despite the cursory dialogue, there’s a poignancy in the way Julie and Jean address each other: at once intimate and alienated, conspiratorial and conflicted. The second segment sees Julie bending before the birdcage, greeting the bird and trying to catch it. As in the opening of the film, she calls the bird ‘sweetheart’. For her, it would seem, the creature is a valentine or flame: there is both complicity and alterity in her relation to it; it exists as much for her as for itself. This contrasts with Jessica Chastain’s Julie, for whom the bird is a transitional object, like a teddy bear, with very little ‘for itself’ or alterity.1 Where Ullmann’s Julie is always and forever a child, Figgis’ is an adult, free and responsible.

1 – Recall her sitting on her bed, cradling the birdcage: she may as well have been sucking her thumb.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

When, in the final segment of the sequence, Julie delivers her tirade, her stern indignation is persuasive, her anger and violence convincing, because we see that her ambivalence is no longer tenable: she must either uphold or abandon her ‘self’. Her rage is directed at Jean, to be sure, for he incarnates the fate that has forced her to assume the consequences of a decision she must now make, but it is also a form of bravado to boost her own courage: in choosing her self, she is choosing the radical isolation of all those who abandon the illusions that make life easier to bear. Julie’s tirade, then, is composed of both bravado and vengeance: it is at once inner- and outer-directed. The outburst of Ullmann’s Julie, in contrast, comes across as having more to do with the regulation of frustration than with a real relation to an other. As such, Ullmann’s Julie becomes a psychological ‘case’, whereas Figgis’ is a free woman with agency. Who has made the more feminist film?

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

The emblematic moment of this sequence comes when Julie, her rage just about spent, repeatedly hits Jean, who parries her punches. Exhausted, she leans into him; like boxers clinching, they embrace. For a moment she is suspended between kissing and crying, her face hardly an inch from his. Finally, she falls out of his arms and onto the floor. There’s something transcendent about this moment; there’s a truth to it that is touching, for it seems to be at once the inevitable outcome of everything that’s gone before and a reprieve of grace before the equally inevitable suicide that will seal the heroine’s fate. Needless to say, if the sequence works so well, it is largely because Saffron Burrows knows that Strindberg’s highwire viciousness works best when the actress holds back neither the physicality of her presence nor the alertness of her intelligence. Never making a misstep, her performance is a triumph.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

XIV. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 14

Julie & Kristin – What if all three of us were to go abroad together?

LIV ULLMANN

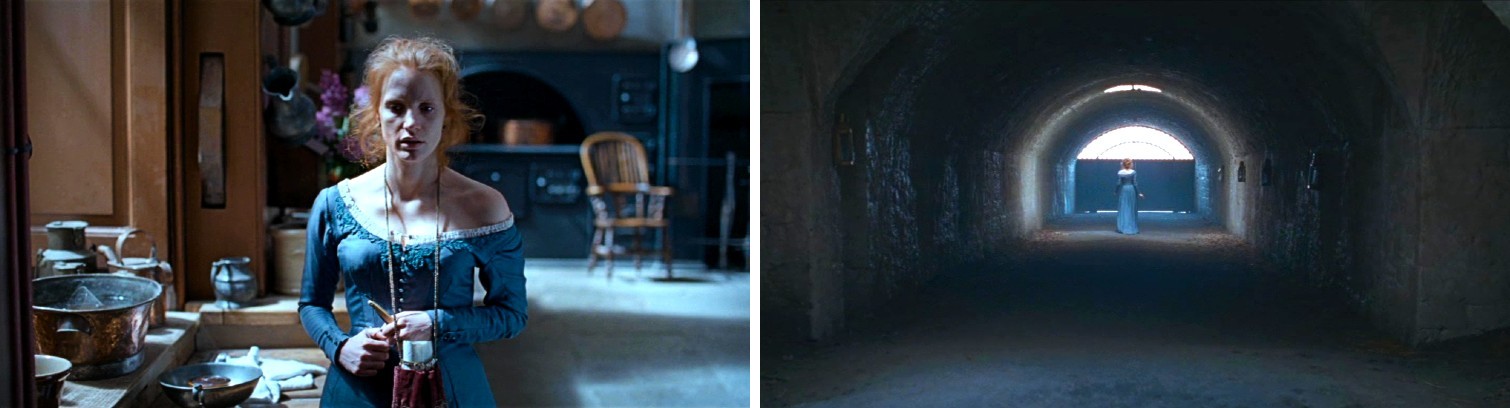

Understanding that she could never twist Miss Julie into a ‘life-affirming’ movie, let alone an ‘uplifting’ one, Liv Ullmann opted to translate, edit and add to it from a ‘feminist’ perspective. As I have argued throughout this essay, the result is in fact anti-feminist, if ‘feminist’ is defined as respect for women’s freedom and responsibility, agency and subjectivity, and initiative and independence. Indeed, Liv Ullmann turns Jessica Chastain into a dependent Julie, anxious and fearful, powerless and ineffectual, in desperate need of guidance and approval. My point is not to dispute that from the fuck to the suicide constraints induced this state, but rather to assert that, faced with this state, the director can have Julie either submit to it or resist it. Mike Figgis chose to have Julie resist it; Liv Ullmann had her submit to it. Indeed, Ullmann has Chastain play Julie in full ‘mad Ophelia’ mode, but, as the actress is twice as old as Ophelia, the effect is simply pathetic. This Julie lacks the dignity of Ophelia’s self-affirmation, of madness as a last refuge for a self under siege. There in no grace in her grovelling, no resistance in her submission. What is Ullmann aiming at? Does she want us to pity Julie? Equate ‘woman’ and ‘victim’? Lament the fact that society is ‘unfair’? In her self-assigned feminist mission the director, it would seem, prefers ideology to art, ‘correctness’ to contradiction.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

In Figgis this sequence is sublime, because Julie fights back her tears even as they fall, fights for her dignity even as she crawls, and fights to believe in the face of her disbelief. The walls of her world may be closing in on her, her youthful insouciance may be a distant memory, but she will not succumb without a struggle. In these dire circumstances Julie’s fighting spirit remains alive, and Saffron Burrows incarnates it in the fullness of her vitality. Unlike in Ullmann, Figgis does not film an acting performance, but the unfolding of a drama. In the service of the story, mise-en-scène, cinematography, editing and acting all concur to sculpt emotion in space and time: the cross-cutting of gazes, the interplay of angles, the rhythms of silence and sound between Christine, Julie and Jean are strikingly effective. Take the cook: Where Ullmann’s Kathleen is a monolithic block of sanctimony, Figgis’ Christine is an earthy incarnation of daring and prudence, female wile and pride. Maria Doyle Kennedy’s performance in the role is scintillating; she radiates self-assurance and authority as well as a certain compassion and pity. All of this is communicated not through a solo performance for the camera, as in Ullmann, but through a fully cinematic interplay of all the elements of filmmaking. Ullmann’s Kathleen is a one-note drone; Figgis’ Christine is a series of chords and arpeggios. As for Julie, Ullmann’s is a diva; Figgis’ a jazz singer. And Jean? Ullmann’s is a choirboy taking a solo turn; Figgis’ is a barroom crooner aspiring to a concert hall. Figgis, unlike Ullmann, knows how to hold the two poles of a contradiction in tension while appealing to both our emotions and intelligence.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

XV. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 15

Julie, Jean & Kristin – Oh, if only I had your faith. | God’s grace isn’t given for everyone to receive.

LIV ULLMANN

This sequence shows just how mistaken Liv Ullmann was in having Samantha Morton’s Kathleen echo the acting style of Jessica Chastain’s Julie. For the entire 4m20 of its duration, Morton adopts the arch-earnest style of Chastain, but where Chastain does it in a ‘little-girl-lost’ mode, Morton does it in a ‘big-mama-knows-best’ one. Morally, Julie is infantilized and Kathleen ‘giantized’: two sides of the same coin, they doubly undermine the drama, for it is with organic characters, not moral ciphers, that drama becomes vital. This problem is compounded by the ‘mechanical’ nature of the editing. Indeed, of the sequence’s 29 shots, 24 are in shot-reverse shot ‘pairs’, with both shot and reverse shot systematically on the speaker (not the listener or some object in the room). This is the lazy editing of bygone television drama: the toolkit of cinema is not called upon. In her suppression of contradiction Ullmann is not Strindbergian, and in her film vocabulary and syntax she is not cinematic. If the cinematic deficit can be ascribed to incompetence, the suppression of contradiction is due to a wilful attempt to graft an ideological construct—’feminism’, ‘listening’, ‘everybody should like everybody’—onto a work whose ‘immune system’ rejects it. Indeed, Strindberg’s is a work of integrity that attacks any foreign construct that attempts to graft itself onto it. If Ullmann’s Miss Julie falls flat, this is one of the main reasons why.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain & Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

Again, Figgis’ 360° cinema immerses us in the drama; the camera takes us to the actors, we feel the cut and thrust of their speech and gestures. At least as much as the dialogue, the marriage of cinematography and mise-en-scène animates the drama. Where Ullmann’s compositions are static and frontal, recalling the stage, Figgis’ are cinematic, dynamic and varied in angle. His ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’ constantly evokes ‘becoming’, the process of dramatic give-and-take, the rise and fall of tension. Ullmann, in contrast, films ‘finished’ images, the product of intellectual projection, bearing no tension. Where she favours the solidity of right angles in compositions that are hard-framed, self-contained and flat, he goes for the unpredictability of the oblique in fluid, open images with depth.1 The style Figgis has invented, seemingly rough-and-ready but in fact highly choreographed, expresses both Strindberg’s naturalist impulse (‘rough and ready’) and his aspiration to tragedy (‘highly choreographed’).

1 – And, as we see in the images below, a rich play of directional forces.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan

As for the actors, I can only salute, once more, their performance. Unlike in Ullmann, where the actors take turns reciting their lines (appear-recite-disappear), in Figgis we have true ensemble acting. Indeed, the energy that circulates between the actors prompts each of them to find just the right timing and intensity, quality of listening and tone of speaking, to generate both emotional and intellectual truth. Finally, observe how astutely Figgis uses close-ups. They create, of course, a sense of intimacy, but also—particularly important in Miss Julie—they enable us to see, registered on a face, the shifts of power between the characters, the domination and subjugation so central in Strindberg.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy, Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan

XVI. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 16

Julie & Jean – Take the broom. You’re not one of the first anymore. You belong to the last.

LIV ULLMANN

To sentimentalize suicide is obscene. And yet, in the final sequence of her film, this is exactly what Liv Ullmann does.

Voluntary death is and always has been an extraordinary act that goes beyond the customary ordering of individual and social existence; this it has been even in circumstances where it has been socially accepted as a duty of honor or as an obligation of taste or even as an order in the name of an unwritten officer’s code. Not only that, but one’s basic self is submerged under a fabricated ego that is merely the result of formations and deformations brought about by the medium of society, a further potential source of distortion. The alienations and setbacks one experiences in one’s life could lead to legitimate reasons for choosing a voluntary death, regardless of whether those reasons can be communicated. Hence, the difficulty of trying to understand why someone commits suicide. One is trying to understand reasons expressed in a language that is individually subjective and not persuasive in the language of everyday life. Yet the individual situation, not the social situation, of each suicide’s argument is what must be understood in order to understand why anyone would choose to end their life.1

All the verbiage and gesture that Ullmann has added to (or modified in) Strindberg’s dialogue and stage directions are aimed at heightening the pathos of Julie’s suicide. The attempt backfires, for any viewer with a modicum of intelligence understands that neither ‘the language of everyday life’ nor the ‘social situation’ have any purchase on the suicide’s reasons for killing herself. Yet Ullmann goes overboard in reiterating reasons, providing explanations, and dispensing sentimentality to such an extent that Julie’s suicide ceases to be an act of self-affirmation and becomes, unintentionally, a display of self-alienation.

1 – Jean Améry, On Suicide: A Discourse on Voluntary Death, tr. John D. Barlow (Indiana University Press, 1999) xiv-xv

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

In reclaiming Julie’s suicide for rational discourse Ullmann trivializes it.1 Bad enough, but she makes it much worse by sentimentalizing it. Julie (dialogue added by Liv Ullmann):

I see silver and gold, and all the stars. Just like when I went to sleep as a child. I’m floating out of the window and up to the sky. Such freedom, surrounded by sparkling crystal. And the dark is no longer dark. The whole room is warm and safe like an open fire. It’s you. And I am close to the fire. How nice and warm it is. And it is so quiet and so light.

At the phrase, ‘and the dark’, Julie takes John’s hand in her hands and brings it to her cheek. Throughout the scene, the ‘andante con moto’ movement of Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat major is heard on the soundtrack. Words, gesture, and music, then, all concur to convey an over-the-top sentimentality. ‘Voluntary death is and always has been an extraordinary act that goes beyond the customary ordering of individual and social existence’: Ullmann, instead of bearing witness to Julie’s radical loneliness as she prepares to kill herself, opts instead to smother it in mawkishness.

1 – The mode of art is mythopoetic, not, as Ullmann would have it, discursive.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Note also how Ullmann, in consistently having Julie regress to a childhood state, refuses her the possibility of exercising her freedom and responsibility as an adult. That men infantilize women is a legitimate feminist criticism: that Ullmann infantilizes Julie makes her film anti-feminist. Recall that she opened the film with Julie as a child reading on her bed. Now, at the end of the film, she closes the circle: her script and mise-en-scène make Julie herself ‘a glorious doll, so fair and delicate’ not made for ‘the sorrows of this world.’ Her adaptation of Miss Julie violates the play’s integrity; it is a radical misreading of Strindberg, and it does feminists a disservice. Yes, Liv Ullmann, an admirer of Ibsen, has returned Nora to the doll’s house: freedom is just too frightening. Indeed, in the big wide world, people do not ‘listen to each other,’ and ‘everybody is not nice to everybody’.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

The last segment of the sequence begins with a shot, one-minute in duration, of Julie walking down the servants’ tunnel of the manor house. On the soundtrack we hear, for the umpteenth time, the slow movement from Schubert’s Piano Trio No. 2 in E-flat major. The composer is thought to have based the piece on a Swedish folksong, ‘The Setting Sun’. The music does, indeed, express the sentiment of the lyrics:

See the sun is setting fast

Behind each mountain peak

Ere night comes with dark shadows

You flee, sweet hope now bleak

Farewell, farewell

Ah, the friend’s thoughts are no more

Of his fair and faithful bride1

The music—haunting, funereal, nostalgic—captures this ‘poetic melancholy’ as it marches along. There is no ‘poetic melancholy’ in Strindberg’s play; Ullmann’s laying it on thick for Julie’s suicide is pure emotional pornography: it is obscene.

1 – Swedish Folksong

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

The sequence continues with Ullmann having Chastain go full out, once again, with the ‘mad Ophelia’ motif. I contend that this—exploiting Ophelia for ‘poetic melancholy’—is something only a paint-by-numbers director would do. This is how Ullmann stages the scene: While Julie, sitting on the gravel bed of a stream, half-in half-out, tosses flowers into the water, she says in voice-over:

I’m sending you out into the world. Look. You’re like bright-colored stars. The water is your heaven. Do you know that, my flowers? Yes. Everything is so much bigger than the little pieces. Do you know that?

Ullmann has Julie, before she brings razor to wrist, wax philosophical: ‘Everything is so much bigger than the little pieces’. What does this have to do with Miss Julie? With Strindberg’s sex-and-class war? Nothing. It is a lame paraphrase of Blake’s ‘To see a world in a grain of sand / And a heaven in a wild flower / Hold infinity in the palm of your hand / And eternity in an hour’. From Ullmann’s perspective, this ending is apt, for it is consistent with the bons sentiments that prevail in her movie. From Strindberg’s perspective, it is asinine, a pin-the-tail-on-the-donkey ending for a half-assed film, consistent with the rest of this travesty of his drama.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Feminist critics have written eloquently on Ophelia. Marlene Tronicke, for example, summarizing Elaine Showalter’s history of Ophelia’s representation,1 writes:

Ophelia has evolved into an iconic figure who functions as an ideological blank canvas, mirroring a culture’s values and attitudes towards gender and the role of feminism. Ophelia embodies the whole trajectory of stereotypical female roles, from beautiful young lady and dutiful daughter to madwoman and drowned, innocent victim. In each case, she appears an emblem rather than a character in her own right.2

What cultural ‘values and attitudes towards gender and the role of feminism’ does Liv Ullmann paint onto the ‘ideological blank canvas’ of the ‘iconic figure’ of Ophelia? As one would expect from her anti-feminist interpretation of Julie, she makes Julie/Ophelia into an emblem of all that is retrograde in this regard. In contrast to Kenneth Branagh, for example, who in his Hamlet (1996) had Kate Winslet, as Marlene Tronicke points out, play Ophelia as a rebel, ‘channelling anger rather than distraction’, the look on her face suggesting ‘grave determination’,3 Liv Ullmann has Jessica Chastain inscribe Julie/Ophelia in the quaint clichés of childlike femininity and picturesque madness: clichés feminists deconstructed decades ago.

1 – Elaine Showalter, ‘Representing Ophelia: women, madness, and the responsibilities of feminist criticism’ in Shakespeare and the Question of Theory, ed. Geoffrey H. Hartman & Patricia Parker (Routledge, 1985)

2 – Marlene Tronicke, Shakespeare’s Suicides: Dead Bodies that Matter (Routledge, 2018)

3 – Ibid.

Kate Winslet as Ophelia | Jessica Chastain as Miss Julie

Ullmann violates Strindberg, as pointed out earlier, in making Julie a sexless creature. Having suppressed her sexuality, Julie has no awareness of her body. The vector of sex as protest—essential if Julie is to be more than a mere victim—is thus denied her. And so Ullmann sends her to her death as a lamb1 to the slaughter: a suicide that might have been affirmative and subversive becomes surrender to a ‘natural order’, the mingling of female blood and flowing water. This echoes, in Hamlet, Gertrude’s vision of Ophelia’s drowning. Carol Thomas Neely:2

Gertrude narrates Ophelia’s death without interpretation, as a beautiful, ‘natural’, ritual of passage and purification, the mad body’s inevitable return to nature:

Her clothes spread wide,

And mermaid-like awhile they bore her up,

Which time she chanted snatches of old lauds,

As one incapable of her own distress,

Or like a creature native and indued

Unto that element.

Hamlet, IV vii 175-180

1 – lamb = innocent victim, not responsible creature

2 – Carol Thomas Neely, Distracted Subjects: Madness and Gender in Shakespeare and Early Modern Culture (Cornell University Press, 2004) 55-56

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Marlene Tronicke:

Gertrude’s speech appears both strangely romanticized and detached. She aestheticizes the dying Ophelia. What could otherwise be imagined as agony looks like a peaceful, aesthetically beautiful surrender or indeed embracing of death.1

Like Gertrude speaking of Ophelia, Ullmann aestheticizes Julie’s suicide. The reality of radical loneliness is replaced with the shallowness of sentimentality; the horror of a drawn-out agony is replaced with the prettiness of bons sentiments. The great Bergman actress thus proves herself a poor writer and director. Her Miss Julie is anti-cinematic, anti-Strindbergian, and—the antithesis of what she intended—anti-feminist.

1 – Marlene Tronicke, Shakespeare’s Suicides: Dead Bodies that Matter (Routledge, 2018)

John Everett Millais, Ophelia, 1852 | Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

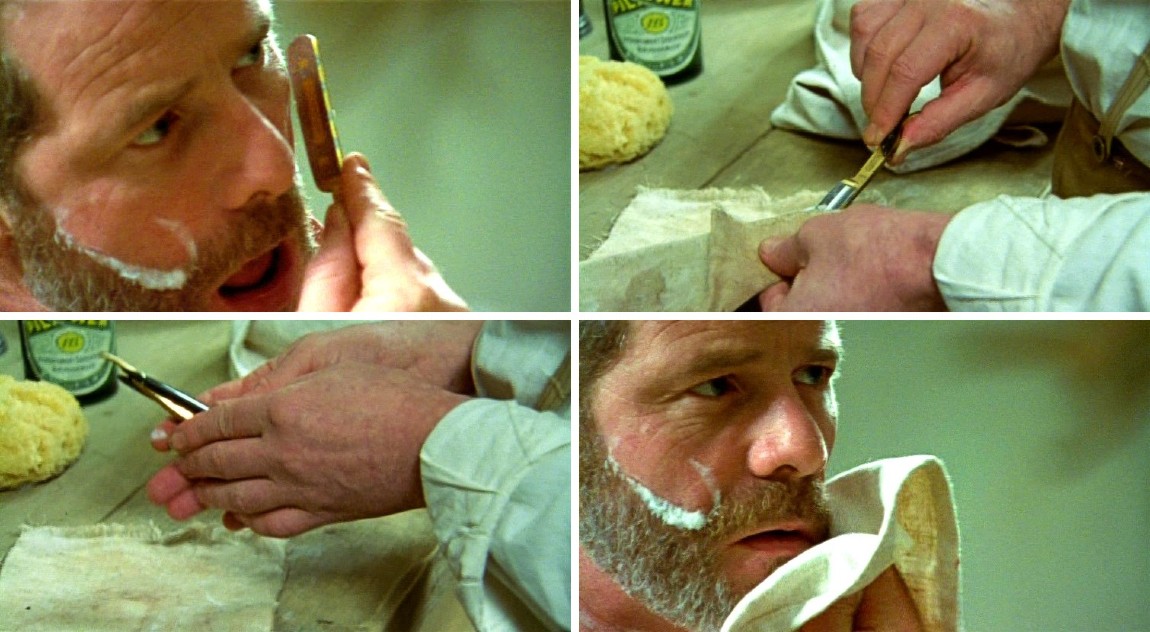

The final sequence of Figgis’ film is at once minimalist and majestic, the sound of silence vying with the bareness of poetry to create the ground against which suicide acquires a stark dignity. The formal coherence of the sequence bears the weight of Julie’s death; its style is conceived to convey the substance of the drama as it draws to a close. Displaying great cinematic intelligence, Figgis trades his ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’ for a mise-en-scène and cinematography of static shots and extreme close-ups, abandoning, as it were, Bertolucci for Robert Bresson. If this sequence were to be written in prose, it would manifest the ‘scrupulous meanness’ of Joyce’s Dubliners. It begins with a close-up of Jean shaving, the silence punctuated by the dripping tap and the crisp scraping of blade across skin. The wiping and folding of the razor, the patting dry of the skin, all concur to give a stickiness to time. The stillness of the space, magnified in the mirror, creates a solemn setting for the impending death.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Peter Mullan

Then, as in a Francis Bacon portrait, Julie’s faces appears distorted in the mirror. Mike Figgis has Saffron Burrows speak in slow, measured tones: with enough gravel in her voice to make it grave, her soft speech is utterly natural. In the entire 7m10 of the sequence, there are only 133 words.1 Virtually all communication is via the face. Visually and aurally, the sequence has a stark simplicity, and yet it conveys a density of emotion that is stunning.

1 – In this sequence, Figgis has 133 words in 7m10, which comes to 1 word every 3.25 seconds. Ullmann has 543 words in 13m45, which comes to 1 word every 1.5 seconds. Paradoxically, it is Figgis, not Ullmann, who has learned the lesson of Bergman’s Persona and The Silence.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

Outside, we hear the sound of running water as Julie, razor in hand, opens the cuff of her sleeve. A piece for string quartet—stark and sombre, with uneasy depths beneath the surface placidity—comes up on the soundtrack. A ringing telephone rudely interrupts it: the Count is calling. Cut to a long shot of the kitchen, now suddenly bare of all the drama it witnessed before. Isolated, as if abandoned, Jean stands alone. He walks to the stained glass door and watches Julie at the well. The water from the tap runs clear across her wrist. Answering the phone, Jean speaks to the Count. We see Julie at the well, in long shot through the open stained-glass door. Out of the strings the musicians now draw a drone. Jean hangs up. As the strings launch into the film’s staccato theme, we cut to a close-up of clear water flowing from the tap. Gradually it begins to turn red. Cut to the kitchen girls fooling around as they enter to perform their morning chores. They do a quick curtsy as they pass Jean with his tray of coffee. Cut to a close-up of the tap, the water now running red. A butterfly—Julie’s soul—flies off. Cut back to the kitchen. The dog eating, the maid sweeping, Jean walking up the stairs. Cut to black. End credits.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

Of a piece with all that preceded it, this is a superb sequence of cinema. Figgis shows just how vital Miss Julie still is today. He found an organic form to express his vision of Strindberg’s drama, a vision grounded in the conviction that struggles arising out of sexual difference are not ideological, as Ullmann would have it, but ontological, inherent in the very make up of man and woman. Sylviane Agacinski:

I see hardly any possibility of thinking critically about sex without the other, and even less of founding a trouble-free sexuality, or finding the general formula for harmony between man and woman. Is that something to be regretted? I don’t think so. Indeed, peace between man and woman would, perhaps, be even more deadly than war between them. Just as democracy is vitalized by the conflicts that shake it up, so love lives thanks to the enigma of the other and the unbridgeable distance between oneself and another.1

At once highly cinematic and utterly Strindbergian, Mike Figgis’ Miss Julie testifies to the truth that ‘we are only alive because we desire, yet in our desiring we are obscure to ourselves’.2 His film, as I’ve tried to demonstrate, attains the status of cinematic art.

1 – Sylviane Agacinski, Drame des sexes: Ibsen, Strindberg, Bergman (Paris: Éditions du Seuil, 2008) 201-202. Translated here by Richard Jonathan.

2 –Adapted from Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery (London: Faber & Faber, 1998) p. 107

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments