TONI MORRISON: ‘BELOVED’ | THE NOVEL | INTERVIEWS AND ANALYSIS

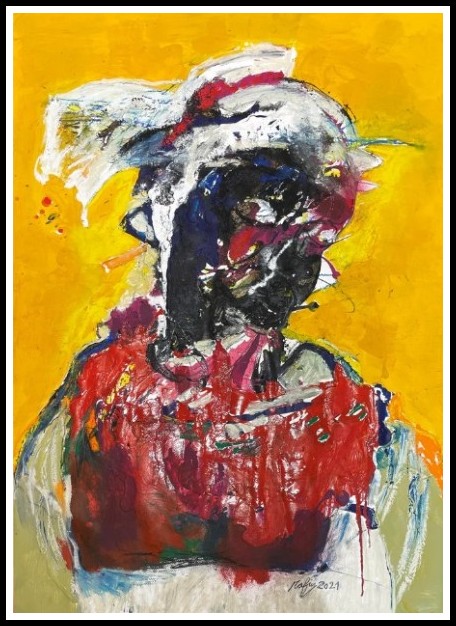

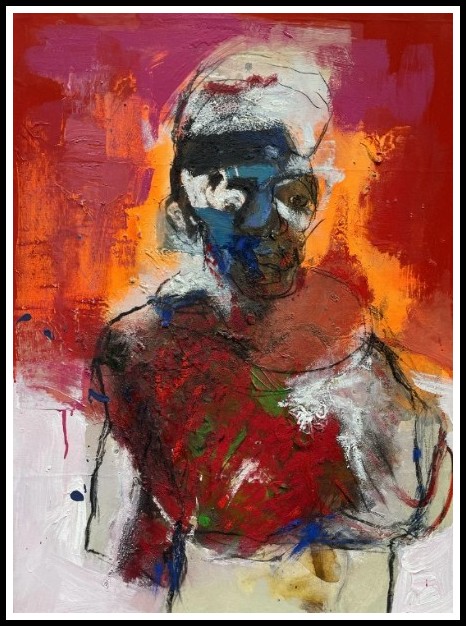

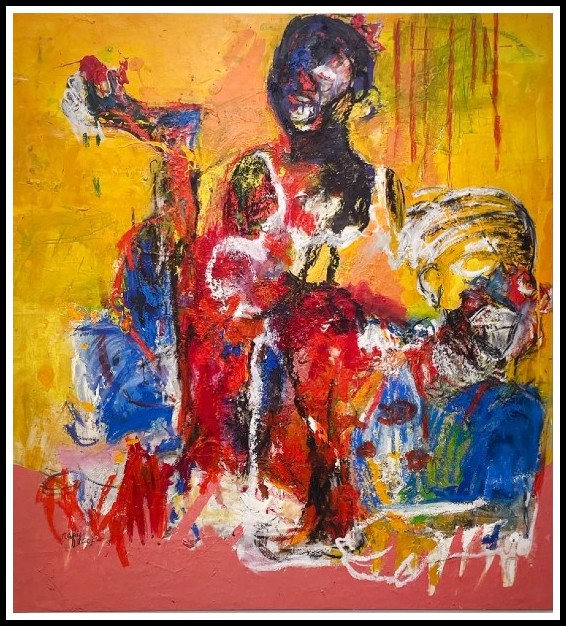

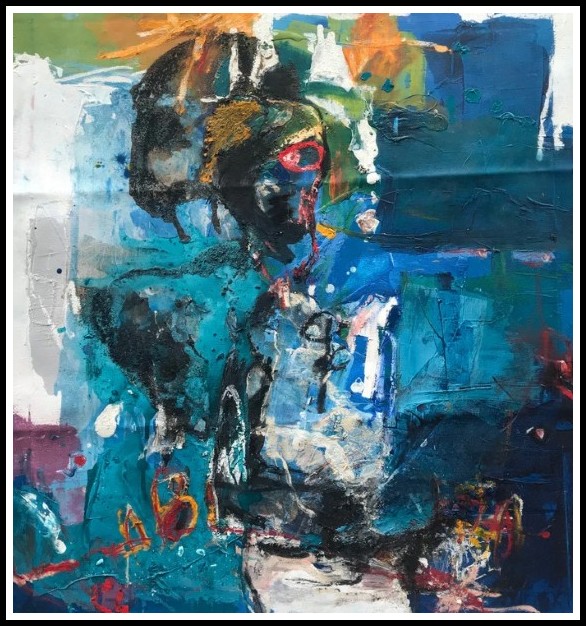

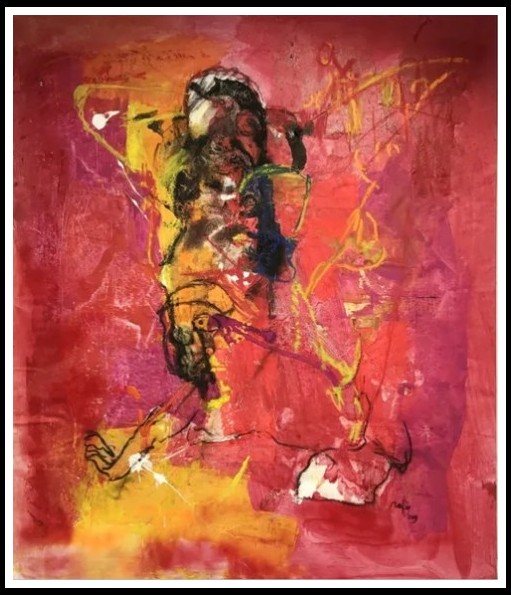

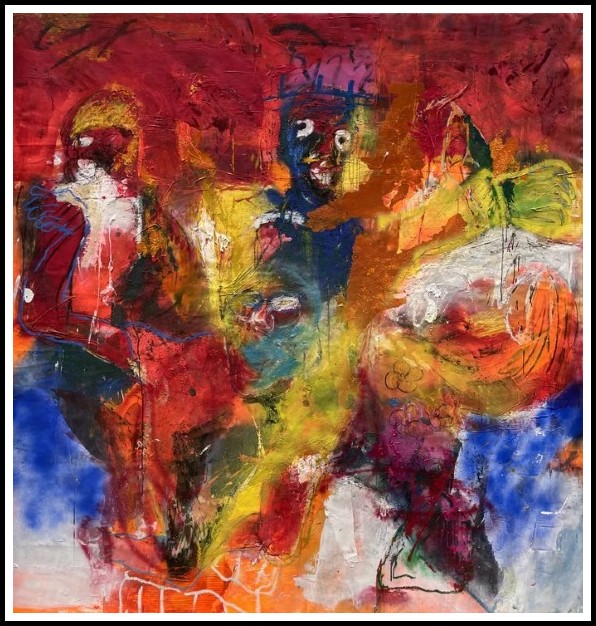

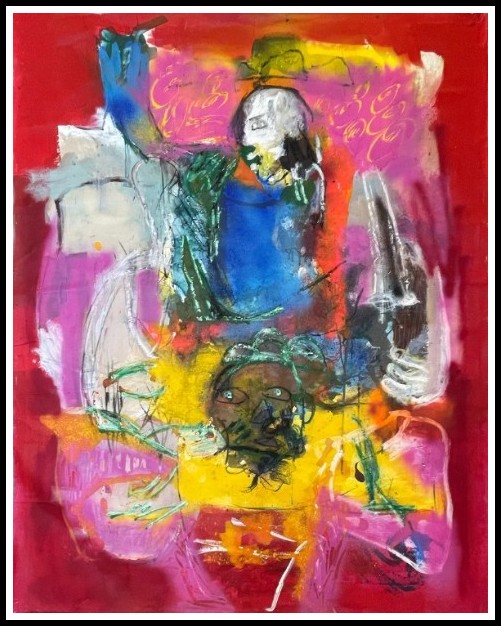

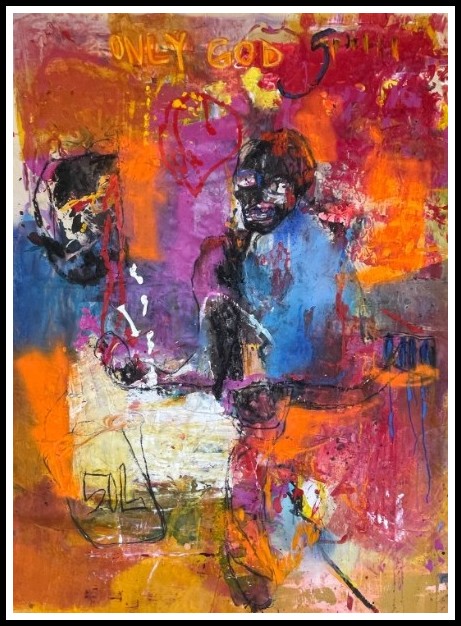

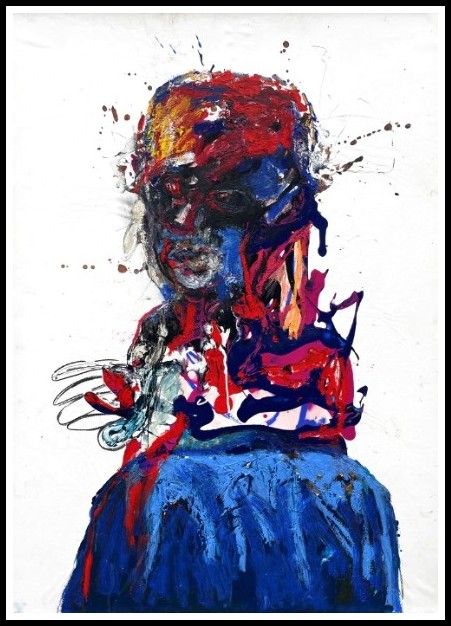

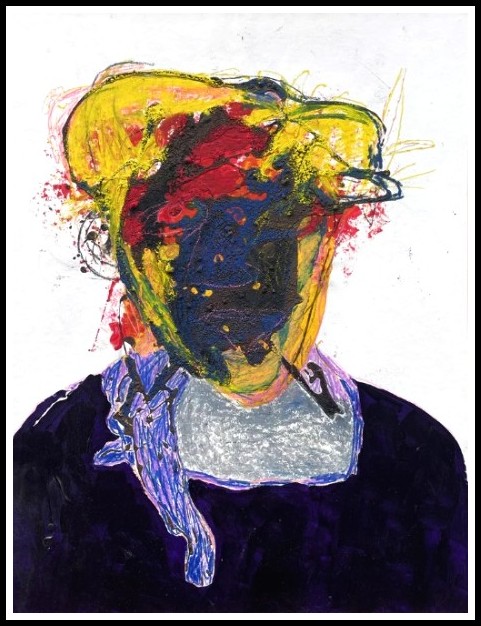

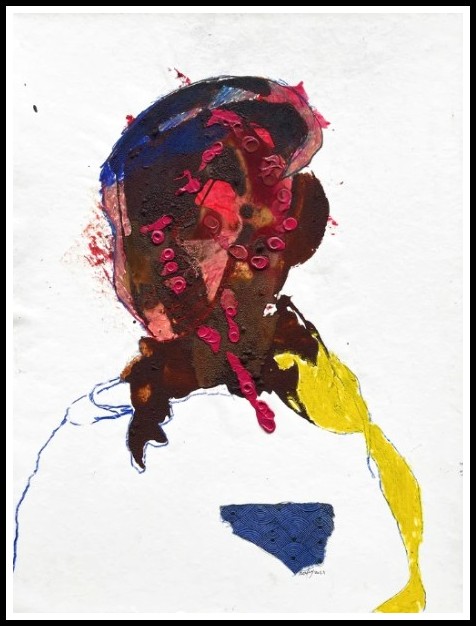

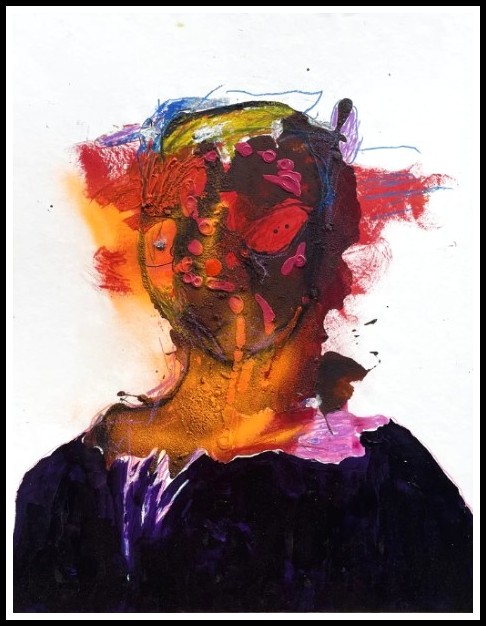

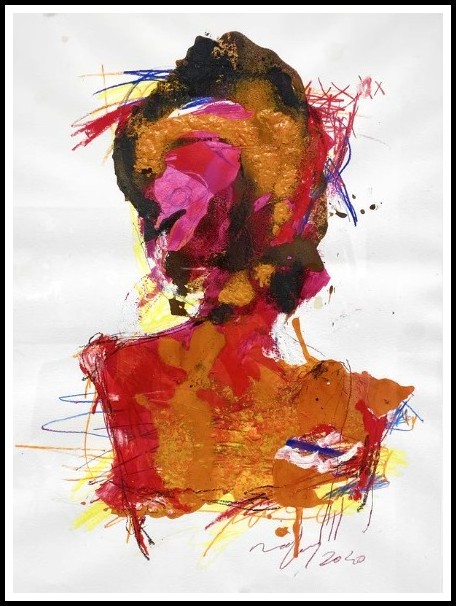

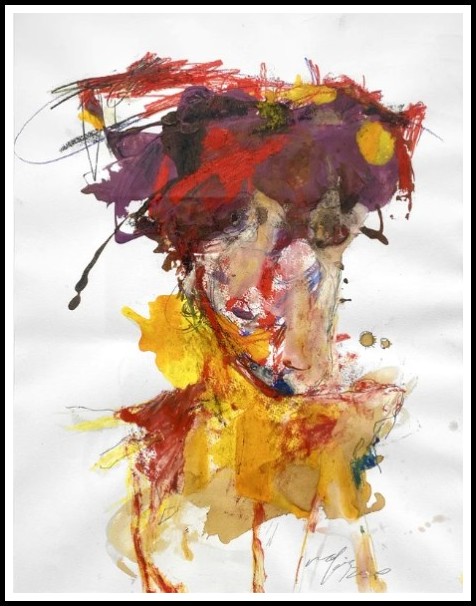

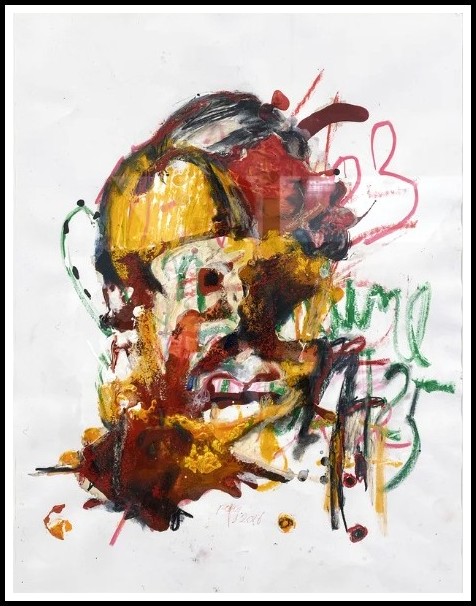

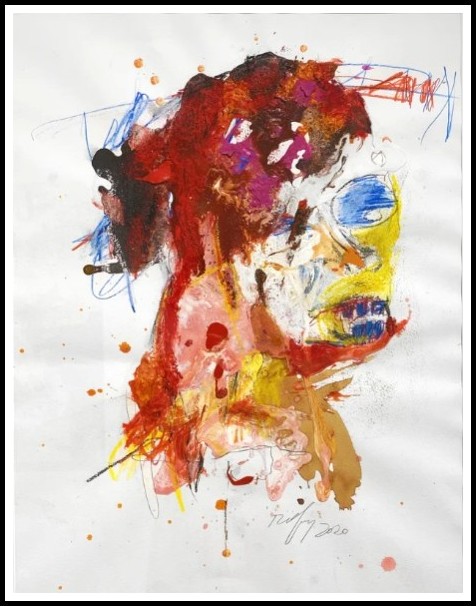

ALL PAINTINGS IN THIS POST ARE BY THE WEST AFRICAN ARTIST, RAFIY OKEFOLAHAN, FROM BÉNIN (FORMERLY DAHOMEY).

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2020

Interview

PART ONE – TONI MORRISON ON ‘BELOVED’

Marsha Darling

Posted by kind permission of Marsha Darling, Professor Emeritus, Adelphi University, New York

From Marsha Darling, ‘In the Realm of Responsibility: A Conversation with Toni Morrison’ (1988) in Conversations with Toni Morrison, edited by Danille Taylor-Guthre (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994) pp. 246-254.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Slave in a Trance, 2020

What are our responsibilities to the living and the dead? What are the boundaries between the living and the dead? For instance, who—what—brings the baby spirit Beloved to 124 Bluestone Road? Is she summoned? Does she come because of some higher law that has not been reckoned with? Reading Beloved got me thinking about cause, effect—what are those boundaries, whose responsibilities? Do you want to suggest that it is Sethe accounting to herself that summons the spirit? Does Beloved bring herself? Does Sethe bring Beloved?

I will describe to you the levels on which I wanted Beloved to function. That may answer the question in part. She is a spirit on one hand, literally she is what Sethe thinks she is, her child returned to her from the dead. And she must function like that in the text. She is also another kind of dead which is not spiritual but flesh, which is, a survivor from the true, factual slave ship. She speaks the language, a traumatized language, of her own experience, which blends beautifully in her questions and answers, her preoccupations, with the desires of Denver and Sethe. So that when they say ‘What was it like over there?’ they mean ’What was it like being dead?’. She tells them what is was like being where she was on that ship as a child. Both things are possible, and there’s evidence in the text so that both things could be approached, because the language of both experiences—death and the Middle Passage—is the same. Her yearning would be the same, the love and yearning for that face that was going to smile at her.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

The gap between Africa and Afro-America and the gap between the living and the dead and the gap between the past and the present does not exist. It’s bridged for us by our assuming responsibility for people no one’s ever assumed responsibility for. They are those that died en route. Nobody knows their names, and nobody thinks about them. In addition to that, they never survived in the lore; there are no songs or dances or tales of these people. The people who arrived—there is lore about them. But nothing survives about… that. I suspect the reason is that it was not possible to survive on certain levels and dwell on it. People who did dwell on it, it probably killed them, and the people who did not dwell on it probably went forward. They tried to make a life. I think Afro-Americans in rushing away from slavery, which was important to do—it meant rushing out of bondage into freedom—also rushed away from the slaves because it was painful to dwell there, and they may have abandoned some responsibilities in so doing. It was a double-edged sword, if you understand me. There is a necessity for remembering the horror, but of course there’s a necessity for remembering it in a manner in which it can be digested, in a manner in which the memory is not destructive. The act of writing the book, in a way, is a way of confronting it and making It possible to remember.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 2, 2021

One of my questions was going to be—and I think you’ve just answered it—where’s the healing? There’s healing in the memory and the re-memory. Yes, each character tells her or his story, and through that there are confrontations with each other; there are a lot of things that go on, yet there’s a healing in bringing it into 1873.

And no one speaks, no one tells the story about himself or herself unless forced. They don’t want to talk, they don’t want to remember, they don’t want to say it, because they’re afraid of it—which is human. But when they do say it, and hear it, and look at it, and share it, they are not only one, they’re two, and three, and four, you know? The collective sharing of that information heals the individual—and the collective.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 3, 2021

Toni, I’ve read articles where people have interviewed you, and you talk about doing research for the book, and how to cast Margaret Garner in a way so as to create Sethe. So some of it you clearly sat down and thought about, did some research about. But there are parts of the book that I am astounded by. For instance: there are sections of the book where you have people thinking to one another telepathically—or at least that’s how I’m interpreting it. Beloved has an extra-human quality about her which for anyone who is psychic is real. When I say it’s an extraordinary book, that’s the level that I’m talking about. This led me to want to ask you, were parts of this book channeled?

I did research about a lot of things in this book in order to narrow it, to make it narrow and deep, but I did not do much research on Margaret Garner other than the obvious stuff, because I wanted to invent her life, which is a way of saying I wanted to be accessible to anything the characters had to say about it. Recording her life as lived would not interest me, and would not make me available to anything that might be pertinent. I got to a point where in asking myself who could judge Sethe adequately, since I couldn’t, and nobody else that knew her could, really, I felt the only person who could judge her would be the daughter she killed. And from there Beloved Inserted herself Into the text. I didn’t start out thinking that would be what would happen in the book. So that when you say ‘channeling’ I’m taking that to mean part of what writing is for me, which is to have an idea and to know that it’s alive, that things may happen to it if I am available to a character or a presence or some Information that does not come out of any research that I’ve done.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

There are times in the book where Beloved speaks and there are times when she thinks. So are you also talking about two different levels of communication?

There are times when she says things, what she’s thinking, when she’s asking something, responding to somebody. The section in which the women finally go home and close up and begin to fulfil their desires begins with each one’s thoughts in her language, and then moves into a kind of threnody in which they exchange thoughts like a dialogue, or a three-way conversation, but unspoken—I mean unuttered. Yet the intimacy of those three women—illusory though it may be—is such that they would not have to say it.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

How is Beloved pregnant?

Paul D.

I know. If she is a human being I could easily comprehend that. That part of the story also forced me to stretch—really stretch.

Nobody likes that part. I know that a couple of people to whom I have said what I just said to you, said ‘I don’t want to know that,’ so I thought, ‘Okay.’ But there is a moment somewhere in time in which that’s what you have to know. That is, ghosts or spirits are real and I don’t mean…

… just as a thought.

That’s right. And the purpose of making her real is making history possible, making memory real—somebody walks in the door and sits down at the table so you have to think about it, whatever they may be. And also it was clear to me that it was not at all a violation of African religion and philosophy; it’s very easy for a son or parent or a neighbor to appear in a child or in another person.

Rafiy Okefolahann, The Silent Witnesses 1, 2023

Does she teach Paul D to call her name, to summon her? She asks him, ‘Call me by my name.’

She tells him that’s what he has to do—so he does. He’s sunk.

I like the men in Beloved. I think I experience Paul D as a healer.

Very much, yes.

Of course we hear his story through his words, but Halle we know by his works, by his deeds, and yet he’s so important to these four children, to Sethe, to Baby Suggs, And we don’t meet him. You obviously were very deliberate about that. Here is a part of the nuclear family in the book and we know him only by his works.

Well, that’s the carnage. It can’t be abstract. The loss of that man to his mother, to his wife, to his children, to his friends, is a serious loss and the reader has to feel it, you can’t feel it if he’s in there. He has to not be there. I was sitting in a radio station somewhere and the man who was interviewing me said, ‘What are you saying about Black women in this book, when Sethe survives and gets across the river and her husband doesn’t?’ And I said, ‘What do you mean?’ And he said, ‘Are you saying that the women are stronger?’ I said, ‘They’re not stronger. What about Halle? You couldn’t ask for a stronger man. He sold his life so that the women and the children could be free.’ This man wanted to engage me in a fake argument, a divisive controversy. I said, ‘Sethe makes it, she’s tough, but some things are beyond endurance and you need some help. So she has some finally from the women and then from Paul D.’

Rafiy Okefolahann, The Silent Witnesses 2, 2023

The notion of the devastation of those families is real, and you can’t communicate how serious it is without indicating that at some point the system will stop you. I don’t want to suggest that slavery was a terrible thing but with a little luck and endurance it was all right. Usually it’s an abstract concept—but I and the reader have to yearn for their company, for the people who are gone, to know what slavery did.

Rafiy Okefolahan, 2019 V

I found myself wondering what difference it would have made if Halle had been there the day that the white men came across the yard to get Sethe, in what was free territory. What difference would his physical presence have made to Sethe’s sense of the possible?

In fact it didn’t make a difference, because Margaret Garner escaped with her husband and two other men and was returned to slavery.

Despite the fact that she killed the child, she was returned?

Well, she wasn’t tried for killing her child. She was tried for a real crime, which was running away—although the abolitionists were trying very hard to get her tried for murder because they wanted the Fugitive Slave Law to be unconstitutional. They did not want her tried on those grounds, so they tried to switch it to murder as a kind of success story. They thought that they could make it impossible for Ohio, as a free state, to acknowledge the right of a slave-owner to come get those people. In fact, the sanctuary movement now is exactly the same. But they all went back to Boone County and apparently the man who took them back—the man she was going to kill herself and her children to get away from—he sold her down river, which was as bad as was being separated from each other. But apparently the boat hit a sandbar or something, and she fell or jumped with her daughter, her baby, into the water. It is not clear whether she fell or jumped, but they rescued her and I guess she went on down to New Orleans and I don’t know what happened after that. The point of all this being that my story, my invention, is much, much happier than what really happened.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Guyane 2019 7

That’s real clear to me. Sethe lives in a world where she gets to be with the man she loves. And she gets to have four children that are by him and she is nineteen, fleeing, running away. And if things look bad, things have not been miserably intolerable…

…not a total dead end, where only death would relieve her. And she gets to have a second shot.

Right. If anything, the fact that she just won’t let all of that be undone, for me, did say something about her being able to pull together over time a sense of her self and a taste of freedom.

Yes, she does have a taste of freedom. And therefore she is able to scratch out something and then maybe more and maybe more. So she can consider the possibility of an individual pride, of a real self which says ‘you’re your best thing.’ Just to begin to think of herself as a proper name—she’s always thought of herself as a mother, as her role.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

I wanted to ask you about your sense of Sethe as mother, woman. There is a way that she loves that is intense. And I’m not sure where I see you locate her self. She tells us at one point that she is not separate from these children; she is these children and these children are her. Could you talk some about that? That is a real powerful part of the book and very controversial, in that she takes responsibility for the very breath in their bodies.

Under those theatrical circumstances of slavery, if you made that claim, an unheard-of claim, which is that you are the mother of these children—that’s an outrageous claim for a slave woman. She just became a mother, which is becoming a human being in a situation which is earnestly dependent on your not being one. That’s who she is. So to claim responsibility for children, to say something about what happens to them means that you claim all of it, not part of it. Not till they’re five or till they are six, but all of it. Therefore when she is away from her husband she merges into that role, and it’s unleashed and it’s fierce. She almost steps over into what she was terrified of being regarded as, which is an animal. It’s an excess of maternal feeling, a total surrender to that commitment, and, you know, such excesses are not good. She has stepped across the line, so to speak. It’s understandable, but it is excessive. This is what the townspeople in Cincinnati respond to, not her grief, but her arrogance.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

Is that why they shun her? They go away, they leave, they just abandon her.

They abandon her because of what they felt was her pride. Her statement about what is valuable to her—in a sense it damns what they think is valuable to them. They have had losses too. In her unwillingness to apologize or bend… she would kill her child again is what they know. That is what separates her from the rest of her community.

And what they punish her for.

Oh, very much.

I actually like that part of the book. I know Black people like that.

Sure. One of the things that’s important to me is the powerful imaginative way in which we deconstructed and reconstructed reality in order to get through. The act of will, of going to work every day—something is going on in the mind and the spirit that is not at all the mind or the spirit of a robotized or automaton people. Whether it is color for Baby Suggs, the changing of his name for Stamp Paid, each character has a set of things their imagination works rather constantly at, and it’s very individualistic, although they share something in common. So it’s important to me that the interior life of each of those characters be one that you could trust, one that felt like it was a real interior life; and also be distinct one from the other, in order to give them—not ‘personalities,’ but an interior life of people that have been reduced to some great lump called slaves.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Only God, 2021

I had started reading Beloved about two and a half months ago, and it got to the point where Beloved and Sethe would enter my dreams and I knew that part of the reason was that I was being so in earnest about the book, reading it at such close attention, because I was going to review it. But I also thought that it had to do with the clarity and the intensity of how I could experience them as characters.

That’s good. Because the whole point is to have those characters, and any that I do, if they’re successful, move off the page and inhabit the imagination of whoever has opened herself or himself to them. I don’t want to write books that you can close and walk on off and read another one right away—like a television show, you know, where you just flick the channel. It’s very important to be as discreet as possible, that the writing be as understated and as quiet as possible, and as clean as possible and as lean as possible in order to make a complex and rich response come from the reader. They always say that my writing is rich. It’s not—what’s rich, if there is any richness, is what the reader gets and brings him or herself. That’s part of the way in which the tale is told. The folk tales are told in such a way that whoever is listening is in it and can shape it and figure it out. It’s not over just because it stops. It lingers and it’s passed on. It’s passed on and somebody else can alter it later. You can even end it if you want. It has a moment beyond which it doesn’t go, but the ending is never like in a Western folktale where they all drop dead or live happily ever after.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Sapataxi, 2018

Toni, the women characters you create are intense, strong, active presences. In this novel they talk to us from the nineteenth century. But you are obviously saying things about the here and now and about women here and now. Could you elaborate on that?

The story seemed to me to yield up a persistent struggle by women, Black women, in negotiating something very difficult. The whole problem was trying to do two things: to love something bigger than yourself, to nurture something; and also not to sabotage yourself, not to murder yourself.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2020

In terms of decisions, choices we make?

Yes. I’ll say it this way. This story is about, among other things, the tension between being yourself, one’s own Beloved, and being a mother. The next story has to do with the tension between being one’s own Beloved and the lover. One of the nicest things women do is nurture other people, but it can be done in such a way that we surrender anything like a self. You can surrender yourself to a man and think that you cannot live or be without that man; you have no existence. And you can do the same thing with children. It seemed that slavery presented an ideal situation to discuss the problem. That was the situation in which Black women were denied motherhood, so they would be interested in it—everybody would be interested in making, holding, keeping a family as large and as productive as it could be. Even though there are greater choices now, an infinite variety of choices, the propensity for self-dramatizing seems to me to be just as great. I’m curious about it, that’s all. For me it’s just an examination of what on earth is going on, what is all this about? And the thread that’s running through the work I’m doing now is this question—Who is the Beloved?

Rafiy Okefolahan, Untitled, 2021

MARSHA DARLING: TWO BOOKS & A CHAPTER

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

Textual Analysis

PART TWO – THE OPENING SENTENCES OF ‘BELOVED’

Toni Morrison

From Toni Morrison, ‘The Opening Sentences of Beloved’ in Barbara H. Solomon, editor, Critical Essays on Toni Morrison’s Beloved (New York: G.K. Hall, 1998) pp. 91-92

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 5, 2021

124 was spiteful. Full of a baby’s venom.

Beginning Beloved with numerals rather than spelled out numbers, it was my intention to give the house an identity separate from the street or even the city; to name it the way ‘Sweet Home’ was named; the way plantations were named, but not with nouns or ‘proper’ names—with numbers instead because numbers have no adjectives, no posture of coziness or grandeur or the haughty yearning of arrivistes and estate builders for the parallel beautifications of the nation they left behind, laying claim to instant history and legend. Numbers here constitute an address, a thrilling enough prospect for slaves who had owned nothing, least of all an address. And although the numbers, unlike words, can have no modifiers, I give these an adjective— spiteful (there are three others). The address is therefore personalized, but personalized by its own activity, not the pasted on desire for personality.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 1, 2021

Also there is something about numerals that makes them spoken, heard, in this context, because one expects words to read in a book, not numbers to say, or hear. And the sound of the novel, sometimes cacophonous, sometimes harmonious, must be an inner ear sound or a sound just beyond hearing, infusing the text with a musical emphasis that words can do sometimes even better than music can. Thus the second sentence is not one: it is a phrase that properly, grammatically, belongs as a dependent clause with the first. Had I done that, however, (124 was spiteful, comma, full of a baby’s venom, or 124 was full of a baby’s venom) I could not have had the accent on full.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 2, 2021

Whatever the risks of confronting the reader with what must be immediately incomprehensible in that simple, declarative authoritative sentence, the risk of unsettling him or her, I determined to take. Because the in medias res opening that I am so committed to is here excessively demanding. It is abrupt, and should appear so. No native informant here. The reader is snatched, yanked, thrown into an environment completely foreign, and I want it as the first stroke of the shared experience that might be possible between the reader and the novel’s population. Snatched just as the slaves were from one place to another, from any place to another, without preparation and without defense. No lobby, no door, no entrance—a gangplank, perhaps (but a very short one). And the house into which this snatching—this kidnapping—propels one, changes from spiteful to loud to quiet, as the sounds in the body of the ship itself may have changed. A few words have to be read before it is clear that 124 refers to a house (in most of the early drafts ‘The women in the house knew it’ was simply ‘The women knew it.’ ‘House’ was not mentioned for seventeen lines), and a few more have to be read to discover why it is spiteful, or rather the source of the spite. By then it is clear, if not at once, that something is beyond control, but is not beyond understanding since it is not beyond accommodation by both the ‘women’ and the ‘children.’ The fully realized presence of the haunting is both a major incumbent of the narrative and sleight of hand. One of its purposes is to keep the reader preoccupied with the nature of the incredible spirit world while being supplied a controlled diet of the incredible political world.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 3, 2021

The subliminal, the underground life of a novel is the area most likely to link arms with the reader and facilitate making it one’s own. Because one must, to get from the first sentence to the next, and the next and the next. The friendly observation post I was content to build and man in Sula (with the stranger in the midst), or the down-home journalism of Song of Solomon or the calculated mistrust of the point of view in Tar Baby would not serve here. Here I wanted the compelling confusion of being there as they (the characters) are; suddenly, without comfort or succor from the ‘author,’ with only imagination, intelligence, and necessity available for the journey. The painterly language of Song of Solomon was not useful to me in Beloved. There is practically no color whatsoever in its pages, and when there is, it is so stark and remarked upon, it is virtually raw. Color seen for the first time, without its history. No built architecture as in. Tar Baby, no play with Western chronology as in Sula; no exchange between book life and ‘real’ life discourse—with printed text units rubbing up against seasonal black childtime units as in The Bluest Eye. No compound of houses, no neighborhood, no sculpture, no paint, no time, especially no time because memory, pre-historic memory, has no time. There is just a little music, each other and the urgency of what is at stake. Which is all they had. For that work, the work of language is to get out of the way.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Portrait of a Soul 4, 2021

‘All my books are questions for me. I write them because I don’t know something.’

PART THREE – THE PRIMARY ROLE OF THE NOVEL

Toni Morrison

From Bill Moyers, ‘A Conversation with Toni Morrison’ (1989) in Conversations with Toni Morrison, edited by Danille Taylor-Guthre (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1994) pp. 272-274. The quote above is on page 270.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Drawing 6, 2020

What do you think is the primary role of the novel? Is it to illuminate social reality, or is it to stretch our imagination?

The latter. It really is about stretching. But in that way you have to bear witness to what is. The fear of collapse, of meaninglessness, of disorder, of anarchy—there’s a certain protection that art can provide in the guise, not even of truth, but just a kind of linguistic shape of a life or a group of lives. Through that encounter, when you brush up against that, if it’s any good, or it touches you in some way, it does really rub off. It enhances. It makes one or two things possible in one’s own life, personally. You see something. Somebody takes a cataract away from your eye, or somehow your ear gets unplugged. You feel larger, connected. Something of substance you have encountered connects with another experience. Novelists can do that. Art can do it in a number of ways. But it certainly should stretch. I don’t want to read a book that simply reinforces all my prejudices and ignorance and things I half-know. I want one that says, ‘Oh, I’d forgotten—but that is exactly the way it looks,’ or ‘Oh, that’s what that feeling is.’

Rafiy Okefolahan, Drawing 4, 2020

That’s what you’ve done for so many others. The paradox to me is that I grew up in a small Southern town in the 1930s and ‘40s and ‘50s—twenty-two thousand people, half black, half white. It wasn’t until I read your novels and the novels of people writing, as you do, about the past that I really knew what the folks on the other side of the tracks were thinking and feeling and experiencing.

That’s important if a book can do that.

If only a book could do it now, for people who are in our circle of the present. Why do we have to wait so long for reconciliation?

You were ready for the information. You were available to the book. Some people are not available to the book, to that information. I’m sure there are books that I am just not ready to hear. It’s not that the novel batters you down and gets rid of barricades or opens doors. The person inside you has to be accessible. There has to be a little crack in there already, some curiosity. Some willingness, you know, to know about it. Some moment when you really don’t have the blinders on. We know people who just zip their eyes shut, who are totally enclosed in the neurotic and frequently psychotic prison of racism. But if ever any chinks can be made from the inside or outside, then they become accessible to certain kinds of information.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Drawing 3, 2017

Are you aware when you’re writing that you’re going to invade my imagination? That you’re going to subvert my perception? Were you intentionally trying to do that?

Totally. I want the reader to feel, first of all, that he trusts me. I’m never going to do anything so bad that he can’t handle it. But at the same time, I want him to see things he has never seen before. I want him to work with me in the book. I can rely on some things that I know you know. For instance, I know you don’t believe in ghosts, none of us do, but—

I wouldn’t go too far in that assumption.

Well, we were all children. We all knew that we did not sleep with our hands hanging outside the bed. To this day if you wake up and your hand is hanging out there you move it back in. So I can rely on readers to know those things. But I do want to penetrate the readerly subconsciousness so that the response is, on the one hand, an intellectual one to what I have problematized in the text, but at the same time very somatic, visceral, a physical response so that you really think you see it or you can smell it or you can hear it, without my overdoing it. Because it has to be yours. I don’t describe Pilate a lot in Song of Solomon. She’s tall and she wears this ear thing and she says less than people think. But I felt that I saw her so clearly, I wanted to communicate the clarity, not of my vision, but of a vision so that she belongs to whoever’s envisioning her in the text. And people can say, ‘Oh, I know her. I know who that is. She is___’ and they fill in the blank because they have invented her.

Rafiy Okefolahan, Drawing 5, 2020

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments