Fini, Colquhoun, Varo, Carrington, Agar, Rahon

WOMEN SURREALIST ARTISTS AND THE HERMETIC TRADITION – PART 2

Whitney Chadwick

Abbreviated from Whitney Chadwick, Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement (London: Thames and Hudson, 1985/2021) pp. 252-277

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE POST – READ PART 1 FIRST

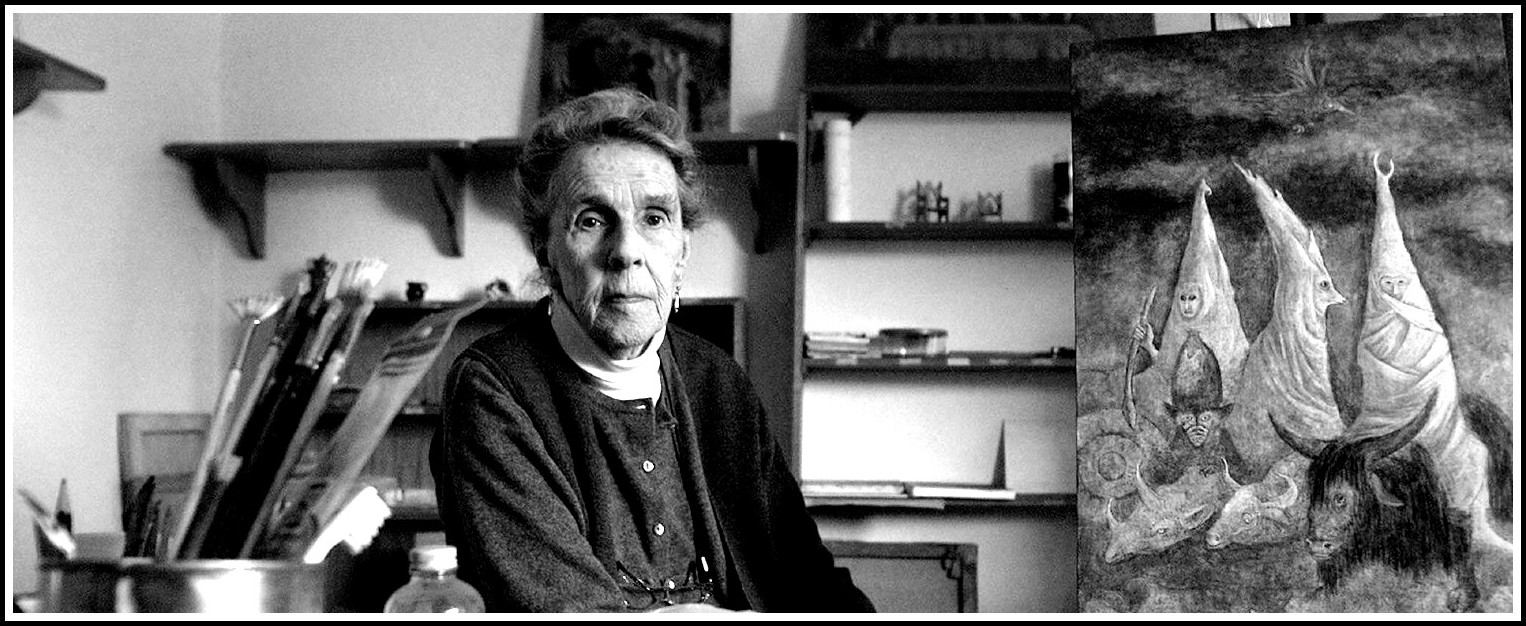

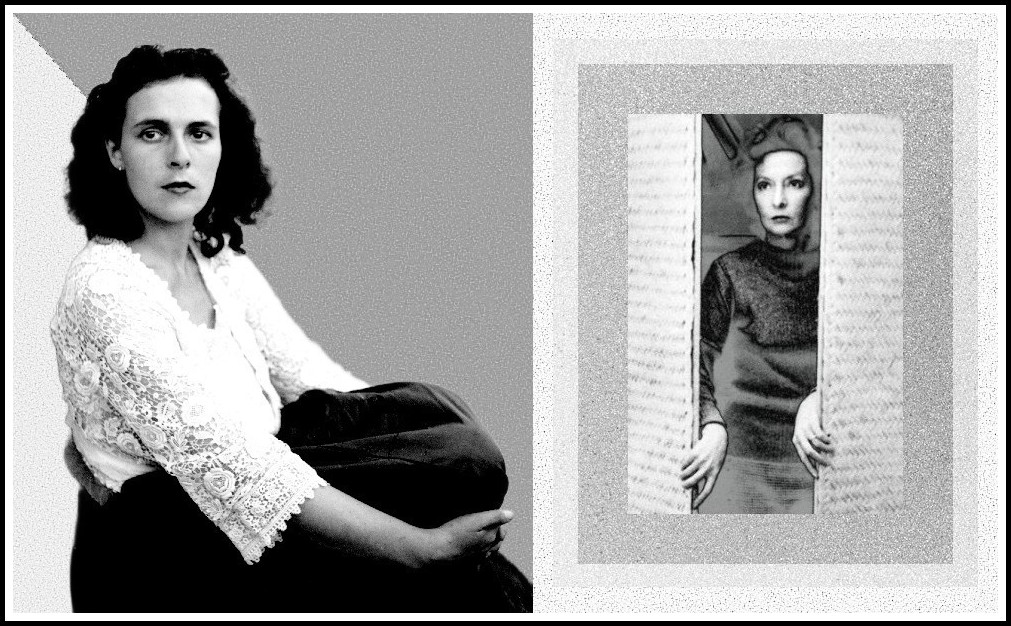

Leonora Carrington, age 84, November 2000 | Photo: Reuters (detail)

In Crookhey Hall (1947), the house from which a young girl flees represents the stifling world of Carrington’s own childhood home.

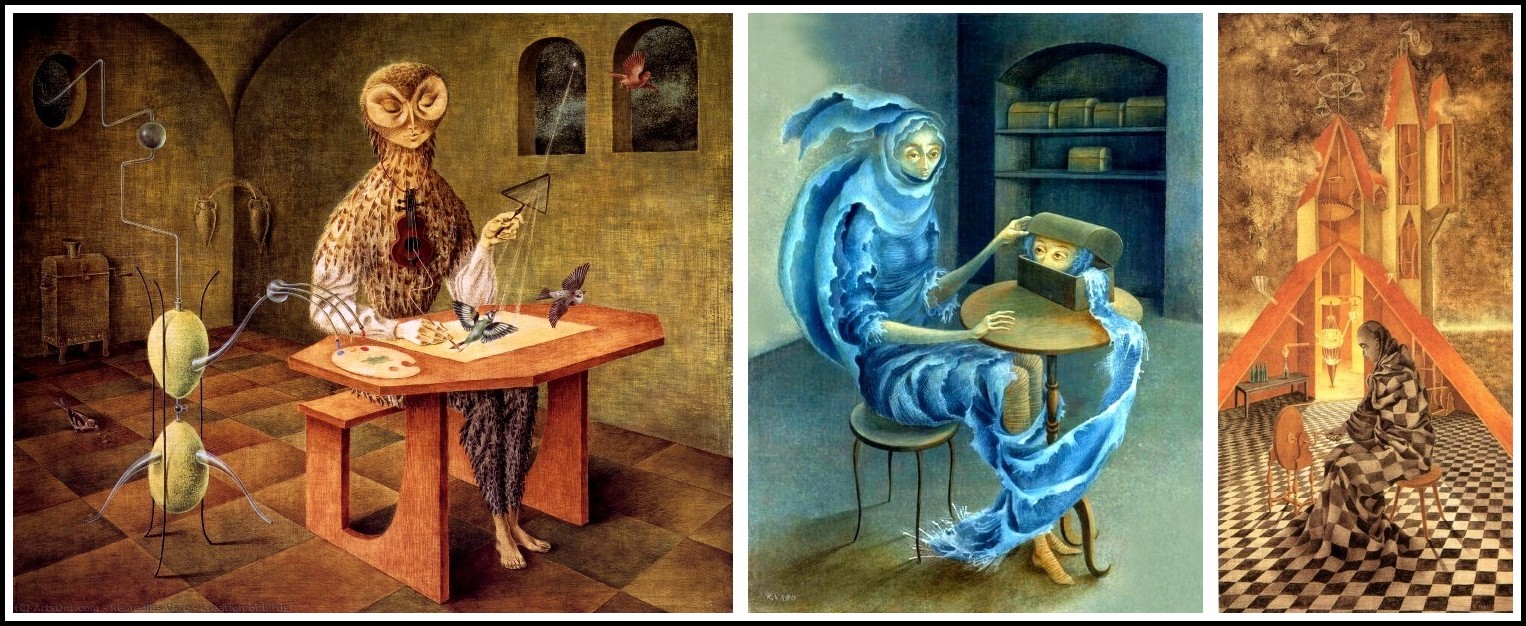

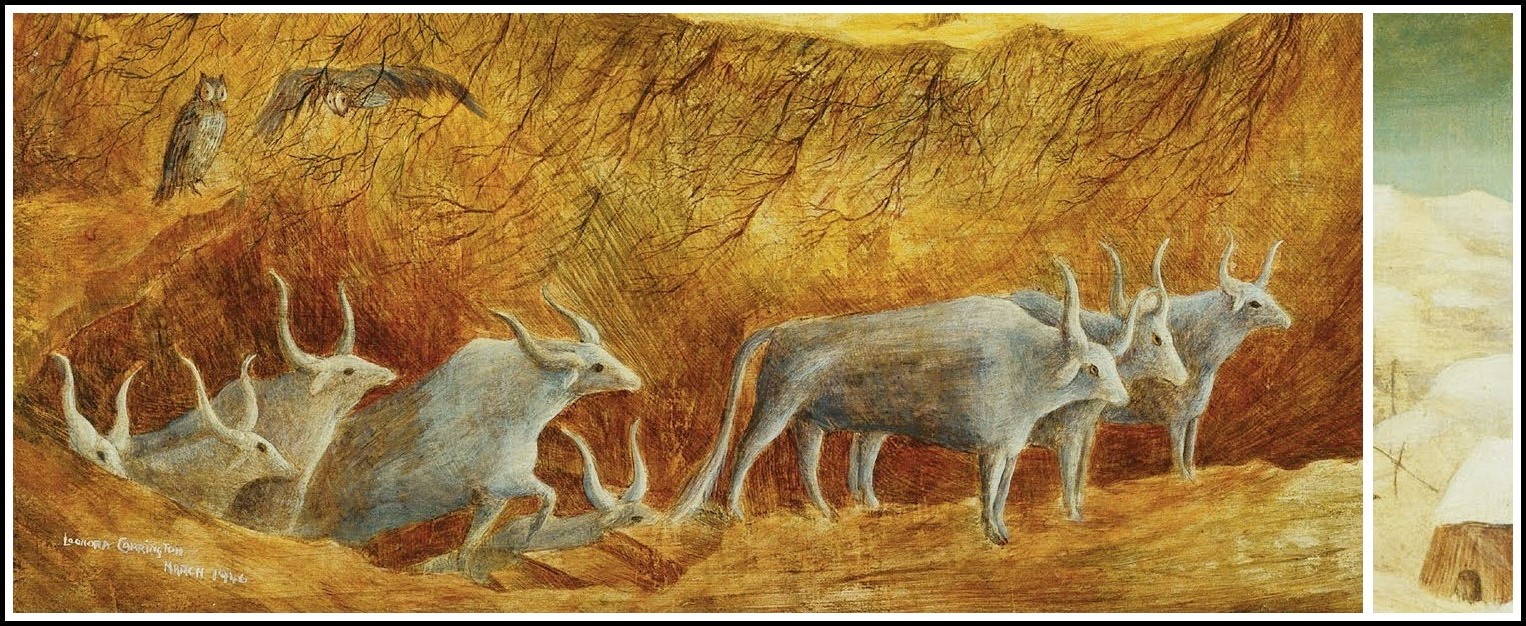

Leonora Carrington, Crookhey Hall, 1947

In Night Nursery Everything, painted in honor of the birth of Carrington’s second son that year, the magical life of childhood takes place in its own domestic domain. In life as well as in art, Carrington grounded her pursuit of the arcane and the hermetic in images of woman’s everyday life: cooking, knitting, and tending children.

Leonora Carrington, Night Nursery Everything, 1947

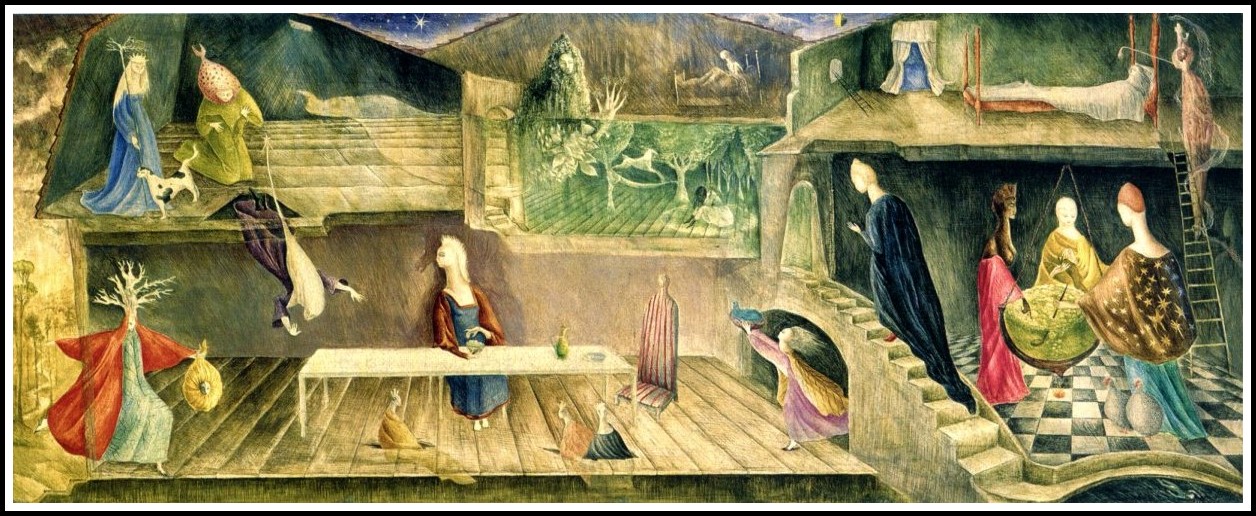

In Mexico, Carrington began painting with egg tempera on gessoed wooden panels, reviving a medieval technique that yielded jewellike tonalities and bright surfaces. Her friend Gunther Gerzso recalls that as she became more conscious of the work of painters like Bosch and Breughel, she became more interested in the technical aspects of painting; the fact that mixing egg tempera seemed to mimic culinary procedure further enhanced its use in her eyes. Experimenting with rapid dislocations of space and scale, she filled her paintings with friezes of tiny figures and fantastic animals. It is only upon careful inspection that one becomes aware of the microscopic worlds of activity that unfold around the edges of her major images, like stories within stories that continually assert the simultaneous existence of more than one world, more than one reality. In The House Opposite, she presents a Celtic-inspired Other World, this one filled with images of resurrection and creation and devoted to a world of women that mirrors that of men. Here the domestic world of the house is presented as a metaphor for the world and conveys suggestions of interior and exterior worlds, higher and lower regions, nature and the firmament (embroidered onto the cape of one of the three figures who stirs a large cauldron). Carrington’s world is a world of fantasy and the imagination in which men are often the enemies of women’s magic powers.

Leonora Carrington, The House Opposite, 1945

The House Opposite includes the world of childhood, also inhabited by a white rocking horse, that of night and the dream, figures who wait and others who are caught in a moment of metamorphosis from plant to human, and finally, a space devoted to the cauldron, prominent in Celtic myth as the cauldron of fertility and inspiration upon which the legend of the Holy Grail was founded. The cauldron in The House Opposite contains a bubbling broth; a small child carries an offering from it to a seated figure who casts a shadow in the form of a horse, suggesting that she already participates in more than one realm of being. The prominent place given to the cauldron in Celtic myth and Grail literature had long fascinated Carrington, as had alchemical descriptions of the gentle cooking of substances placed in egg-shaped vessels. She has related alchemical processes to those of both cooking and painting, carefully selecting a metaphor that unites the traditional woman’s occupation as nourisher of the species with that of the magical transformation of forms and colors in the artist’s creative process.

Leonora Carrington, The House Opposite, 1945 (detail)

It was during this period of close personal exchange of ideas that Carrington and Varo evolved their highly personalized vision of the woman creator whose creative and magical powers were a higher development of traditional domestic activities like cooking. Cooking and eating play decisive roles in both women’s writings. In one of Varo’s unpublished stories, the characters are instructed to follow recipes (formulas) carefully to avoid bad consequences. Her notebooks contain recipes designed to scare away ‘the inopportune dreams, insomnia and the deserts of sand moving under the bed,’ and those arranged to encourage other kinds of nocturnal experiences. A recipe designed to provoke erotic dreams calls for ingredients that include a kilo of strong roots, three white hens, a head of garlic, four kilos of honey, a mirror, two calves’ livers, a brick, two clothespins, a corset and stays, two false moustaches, and hats ‘to taste.’ The instructions that follow parody exactly those of the traditional cookbook. In all of these stories and paintings, women cook the magic brews, tend the alchemical fires, and oversee the cauldron of fertility and inspiration.

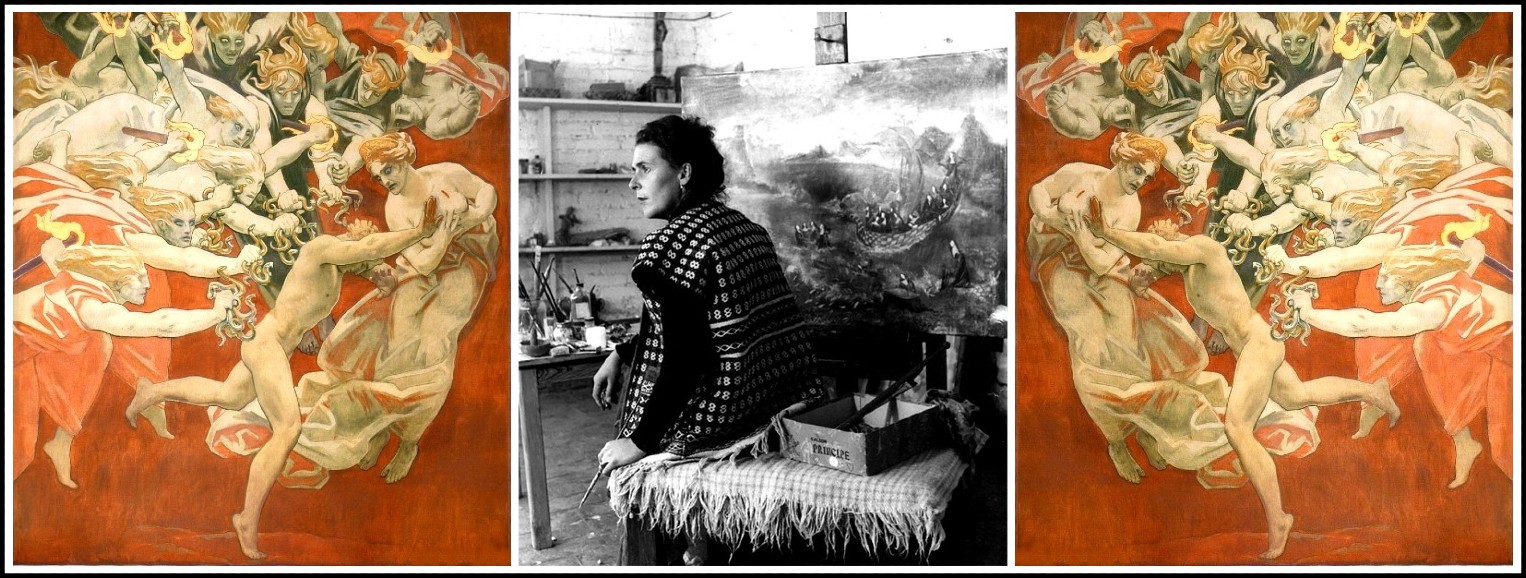

Inset: Remedios Varo & Gerardo Lizarraga, Mexico City | Background: J-G, Unsplash

‘The invisible speaks to us, and the world it paints takes the form of apparitions; it awakens in each of us that yearning for the marvelous and shows us the way back to it,’ wrote Alice Rahon in 1951. Rahon, previously known to Surrealist audiences as a poet, began painting in earnest in Mexico. Her first semi-automatic works originated in a decision to scrape and reuse the surfaces of Wolfgang Paalen’s discarded palettes. She often threw sand and cement over these multicolored grounds in a technique not unlike that of Masson’s sand paintings of the 1920s, and then scratched through the surface layers with a nail to evoke the forms of fantastic architectural vistas, animals, primitivistic stick figures, and hieroglyphic signs. The use of abstract signs by Rahon and others continually reaffirmed the origins of painting in ritual and magic. Of all the European Surrealists working in Mexico, Rahon appears to be the one most directly influenced by the country’s indigenous art, for although Varo was an avid collector of pre-Columbian art, its forms and content play little if any role in her own work and Carrington does not seem to have consciously drawn from this source until the late 1950s.

Alice Rahon, early 1930s (Photo: Man Ray) | Pre-Columbian Gold Pendant, c. 750 A.D.

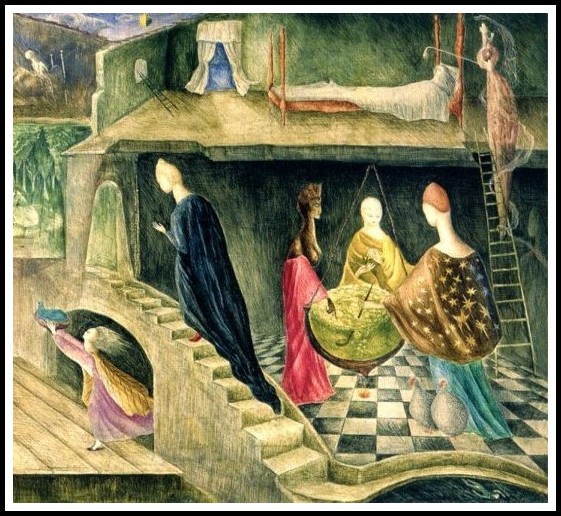

Many of Varo’s paintings reuse and sometimes parody images and themes from Carrington’s work. The black-and-white tile floor of the alchemist’s chamber in Carrington’s The House Opposite reappears in Varo’s later The Useless Science, or the Alchemist: a solitary woman has gathered the black and white squares into a cloak in which she huddles while turning the crank that sets in motion an elaborate mechanical apparatus designed to distill precious liquid from raindrops. Behind her rise the blocky forms of a medieval tower containing a set of gears and pulleys that suspend the alchemist’s alembic over a conical fire. Whether the drops of liquid falling from the sky actually pass through the transforming alembic remains in doubt; they may simply go directly from funnel to spout, water turned into water. Varo has used the Surrealist technique of decalcomania, and the work is bathed with the yellow light described by medieval alchemists. But unlike other Surrealists, she never allowed automatism to dominate her creative process, instead choosing a working method that was meticulous to the point of obsession. When painting she often sequestered herself in her studio for seven or eight hours a day for upwards of a month. The making of the finished work was a matter of meticulous craftsmanship in the deliberate application of tiny brush strokes of color.

Leonora Carrington, The House Opposite, 1945 (detail) | Remedios Varo, The Useless Science, or the Alchemist, 1955

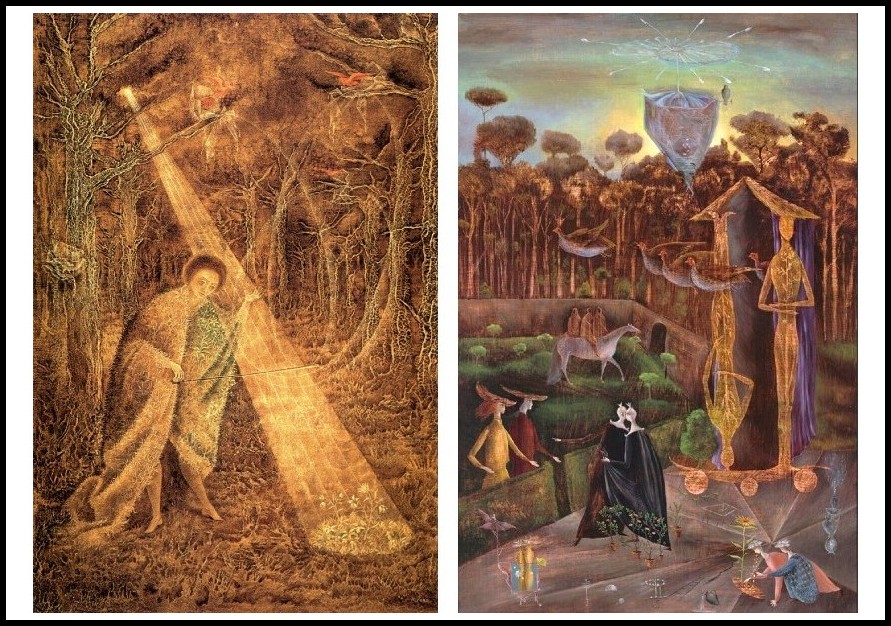

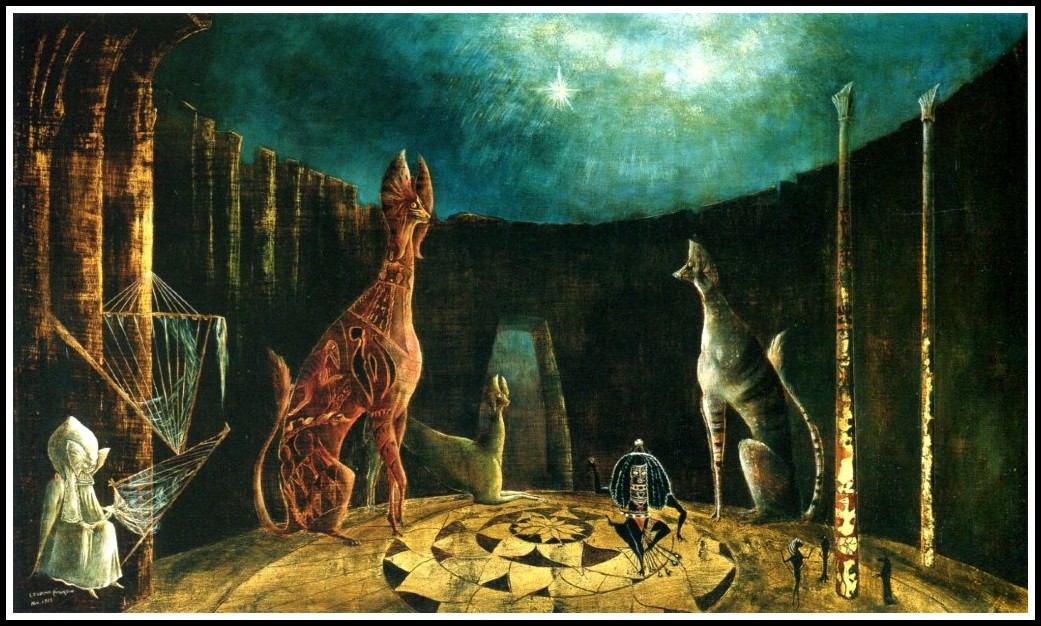

A feeling that elaborate expenditures of energy and complicated mechanical procedures may, in fact, only lead to the obvious, the unchangeable, pervades many of Varo’s works. In The Useless Science, or the Alchemist we are left guessing as to what is ‘useless,’ while in Encounter we are confronted with the uselessness of attempting change. Here a somber young woman opening a box in search of a new persona finds only her own face peering out. On the wall behind are other boxes in varying sizes, but the woman’s unfocused gaze and troubled mien suggest that they also contain the same reality. In other Varo paintings, alchemical apparatus reappears as a device to be used in the creation of both art and life. In The Creation of the Birds, the artist, personified as a wise owl, is seated at a drawing table. With one hand she holds a magnifying glass that transforms the light from a star into the form of a bird on a piece of drawing paper; with the other, she paints in its tail feathers with a brush that is connected to the strings of a violin hanging around her neck. Beside the artist an alembic receives stardust and transmutes it into colored pigment that falls onto a palette. On the wall behind the artist/alchemist two suspended vessels pass their contents back and forth, and newly created birds fly around the room. Varo’s woman/creator creates life as well as art, without the need for the inspiration of the muse or the Surrealist intervention of the loved one, for she herself possesses the secret of all creation.

REMEDIOS VARO

Creation of the Birds, 1957 | Encounter, 1959 | The Useless Science, or the Alchemist, 1955

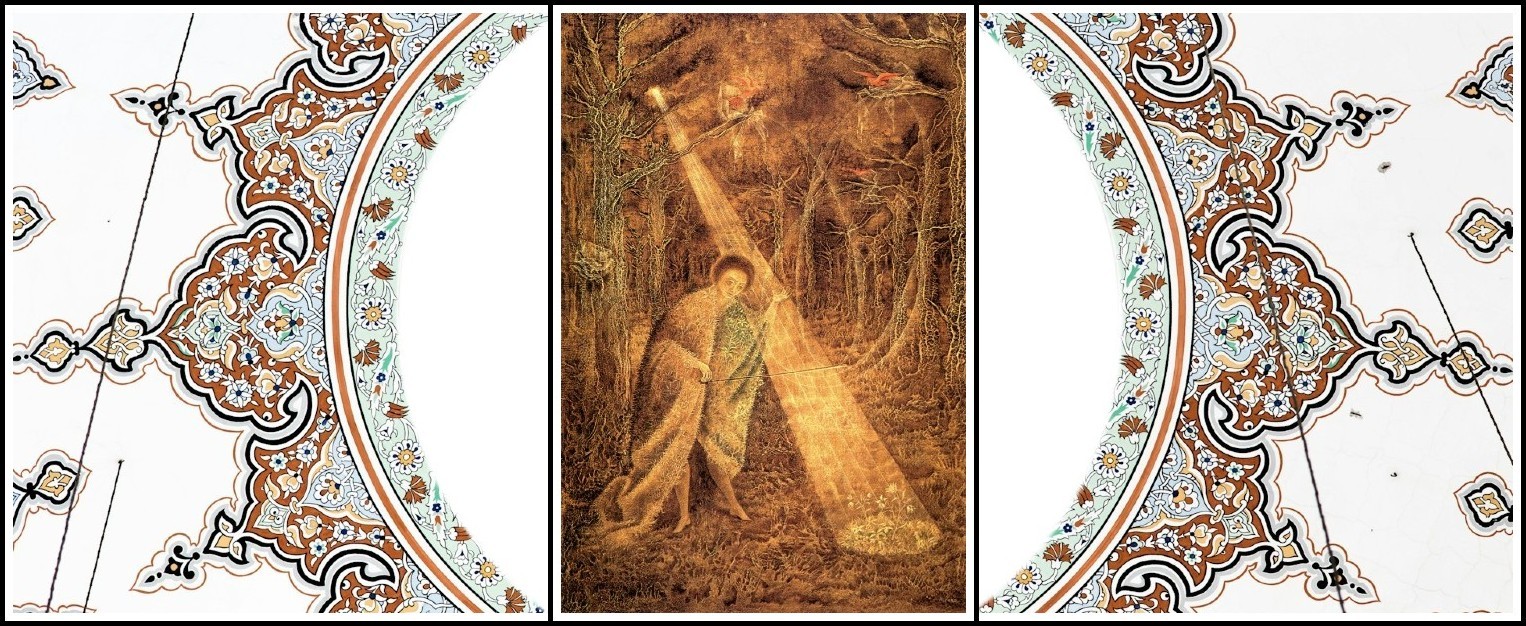

Varo’s The Creation of the Birds turns woman into an image of knowledge and the possessor of secret alchemical powers. It also incorporates ideas drawn from Islamic, specifically Sufi, philosophy, an important source for Western knowledge of medieval alchemy and one surely familiar to the Spanish Varo; her notebooks contain Arabic names and Islamic references and she was a follower of the philosophy of G.I. Gurdjieff, whose belief in the spiritual powers of music and dance had been shaped by Sufi mysticism. According to Sufi belief, light and vibration, or sound, are together the source of all creation. In Varo’s Solar Music, a woman plays a stringed sunbeam with her bow, and the resulting music releases the birds in the trees from their cocoon-like nests and causes grass and flowers to spring from her cloak and the earth to sprout new life where it is touched by the sun’s rays. Through the magical correspondences that exist between light and sound woman becomes the instrument for creating life as well as art.

Remedios Varo, Solar Music, 1955 | Background photo: Cihat Hidir, Unsplash

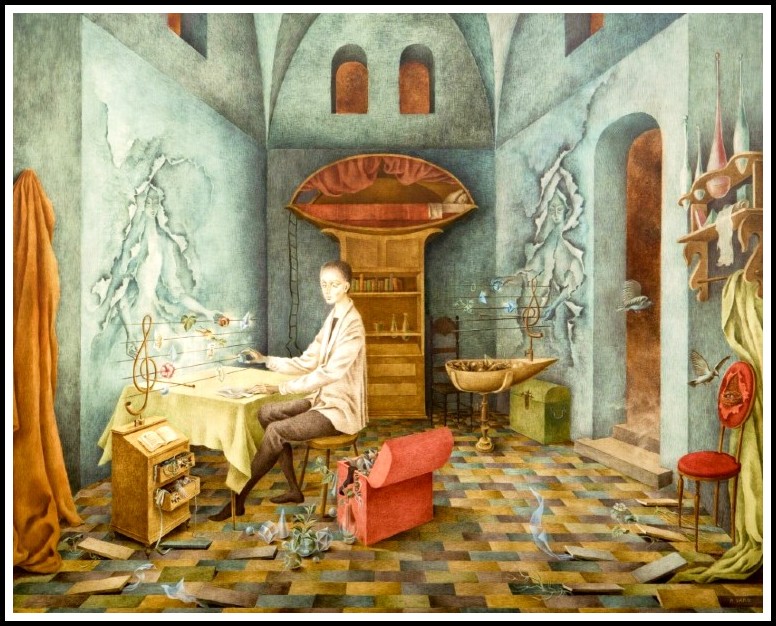

Without these correspondences creativity runs amok. Harmony depicts the struggle to create musical harmony. The crystals, leaves, and seashells manipulated on the staff by an androgynous figure seated at a table, and by the ghostly image of a woman who breaks through the wallpaper, are mirrored by the series of odd events taking place in the room. Drawers spring open to release their contents, floor tiles are pushed aside, and plants and bits of drapery spring into movement in response to the sounds emanating from the two staffs. Confusion reigns in this monastic room, but we sense that it is only a matter of time until the proper correspondences are achieved and a medieval order (harmony) reigns.

Remedios Varo, Harmony, 1956

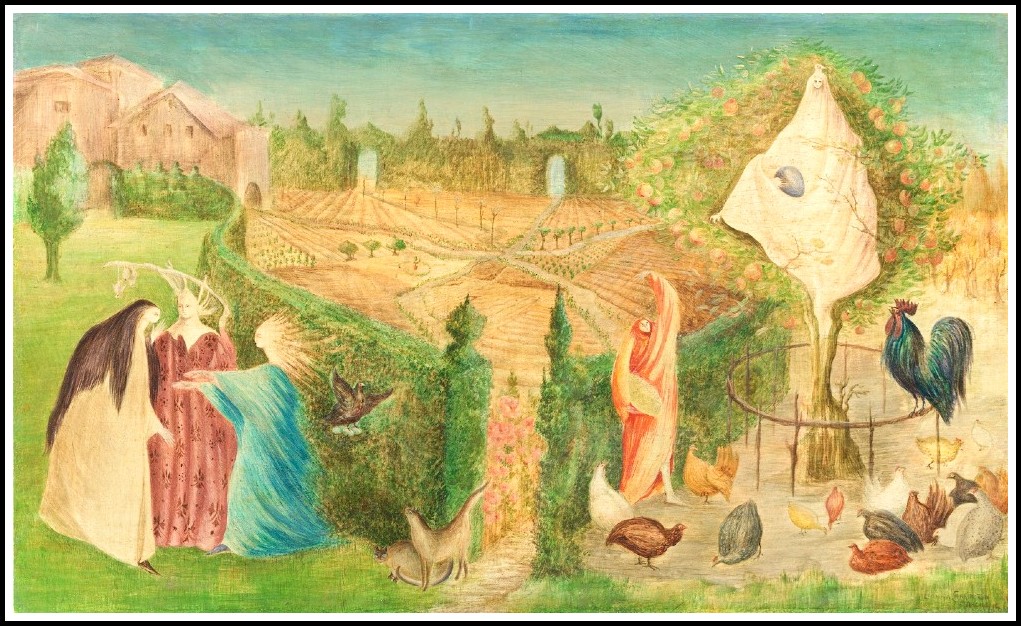

The theme of woman’s role in the creative cycle also underlies much of Leonora Carrington’s work of the 1940s. The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot…

Leonora Carrington, The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot, 1946

…and Amor que move il sole e l’altre stelle contain numerous references to a female creative spirit. Amor que move il sole e l’altre stelle depicts a procession of robed women and young girls who conduct a chariot of the firmament filled with sunlight and stars. The chariot is drawn by a horse whose wings, sprouting from its head in the form of curved horns, suggest the presence of the horned god, a traditional consort of the goddess in ancient religions. The presence of the two fantastic beasts who accompany the chariot suggests that the image has sources in the Tarot pack: the seventh card in the pack is the Chariot card, which indicates the triumph of the higher principles of human nature and which has on it a chariot accompanied by black and white sphinxes. Behind the chariot is a double being, both sun and moon, identified by the crescent shape on the top of one head and the solar rays that radiate from the other. In one hand it holds a fish from the sea in a cradle-shaped net. Carrington’s triumphal procession rolls along as if part of a medieval pageant celebrating the birth of the cosmos, an impression enhanced by the use of delicate blues and golds. In the Celtic legends to which Carrington so often turned, the horned god is the lord of animals and an image of fecundity, an allusion difficult to ignore in this context as the painting is signed and dated 12 July 12 1946, two days before the birth of Carrington’s first son. It was an event that she had anticipated with great excitement and one that may well be intimated here in this triumphant female procession bearing new life and attended by the sun and the moon.

Leonora Carrington, Amor que move il sole e l’altre stelle, 1947

The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot contains at least one of the same figures, the woman robed in a gown reminiscent of Renaissance dress. The presence of other similar female figures, one of whom, eyes closed, brings her vision to the others, also hints at a connection with Amor que move it sole e l’altre stelle. The subject, fertility, encourages further comparison. Kitchen gardens, usually adjacent to or within easy access of the kitchen, provide fresh produce and herbs for the household. Carrington’s kitchen garden is walled like the Virgin’s hortus conclusus and filled with neatly planted rows of fruits and vegetables.

Upper Rhenish Master, The Little Garden of Paradise, 1415

Outside its walls, birds sit on nests full of eggs, fat quail peck for grain, a robed figure holding a large egg sprinkles stardust on its head in a symbolic act of fertilization that is repeated in other Carrington paintings—see, for example, Again the Gemini are in the Orchard—and a white-robed female figure who appears to grow out of the trunk of a fruit tree plucks fruit while cradling a large egg under one arm. The image of the garden, a recurrent motif in alchemical literature, is often used to emphasize the significance of sprouting and procreation. Hermetic parables by Christian Rosenkreutz and others give a central place to the walled garden as one of the oldest and most indubitable symbols for the female body. At least one alchemical practice consisted of putting some gold into the mixture to be transmuted. The gold dissolved like a seed and produced more gold (the fruit); the matter into which the seed was placed and in which germination took place was known as the earth, or mother. Evidence for the existence of similar ideas in Carrington’s work can be seen in Again the Gemini are in the Orchard. In this work the Gemini or Twins, a dual astrological sign for the creative and destructive life forces, stand on a magic ground in which a tiny vessel waters the earth and two small figures wearing flowers on their heads fertilize another flower, just as in Varo’s Solar Music light and sound fertilize the earth.

Remedios Varo, Solar Music, 1955 | Leonora Carrington, Again, the Gemini Are in the Orchard, 1947

Images of eggs and partridge or quail also appear consistently in Carrington’s work. The paintings are never mere illustrations of the ideas of others; instead, images are combined and recombined in order to confound conventional readings and elicit new meanings. In ancient times the partridge was variously identified with the sun or the moon, and was often sacred to the love goddess because of a reputation for licentiousness pointed out by both Aristotle and Pliny. In Carrington’s work it is sometimes used to affirm the earth’s bounty, at other times it becomes a wry comment on country life, and it may even appear as the source of the alchemical egg of rebirth and transformation. The partridge reappears in Carrington’s somewhat ironic painting titled The Late Mrs. Partridge. The late Mrs. Partridge travels with her bird, and also with an egg-shaped handbag. The egg or egg-shaped vessel, a form never far from Carrington’s mind, is one that she shared with many other Surrealists for whom the egg, or egg shape, had alchemical, psychological, or creative significance. The painting called The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) contains two lilliputian worlds in a landscape reminiscent of Breughel. One is of the sea and filled with whales and Viking ships; the other is a hunting scene the ritual and magical aspects of which are indicated by the fantastic animal that flees from the hounds and by the woman who rides in from the left astride a strange horse-like creature. The figure of Baby Giant gently cups a speckled egg in his hands, birds fly out of his cape, and a halo of golden wheat surrounds his head and replaces his hair. These images of generative nature have sources in paintings that also emphasize the image of the egg, such as The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot.

LEONORA CARRINGTON

Portrait of the Late Mrs Partridge, 1947 | The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg), 1947

Carrington’s Who Art Thou White Face?, painted in 1959, gives an even more prominent place to the egg; a Chimaera, the fabulous winged beast on which, according to Robert Graves, Zeus flew up to heaven, binding heaven and earth, and which is always present at the poet’s creative act, stands watch over a large egg.

Leonora Carrington, Who Art Thou Whiteface?, 1959

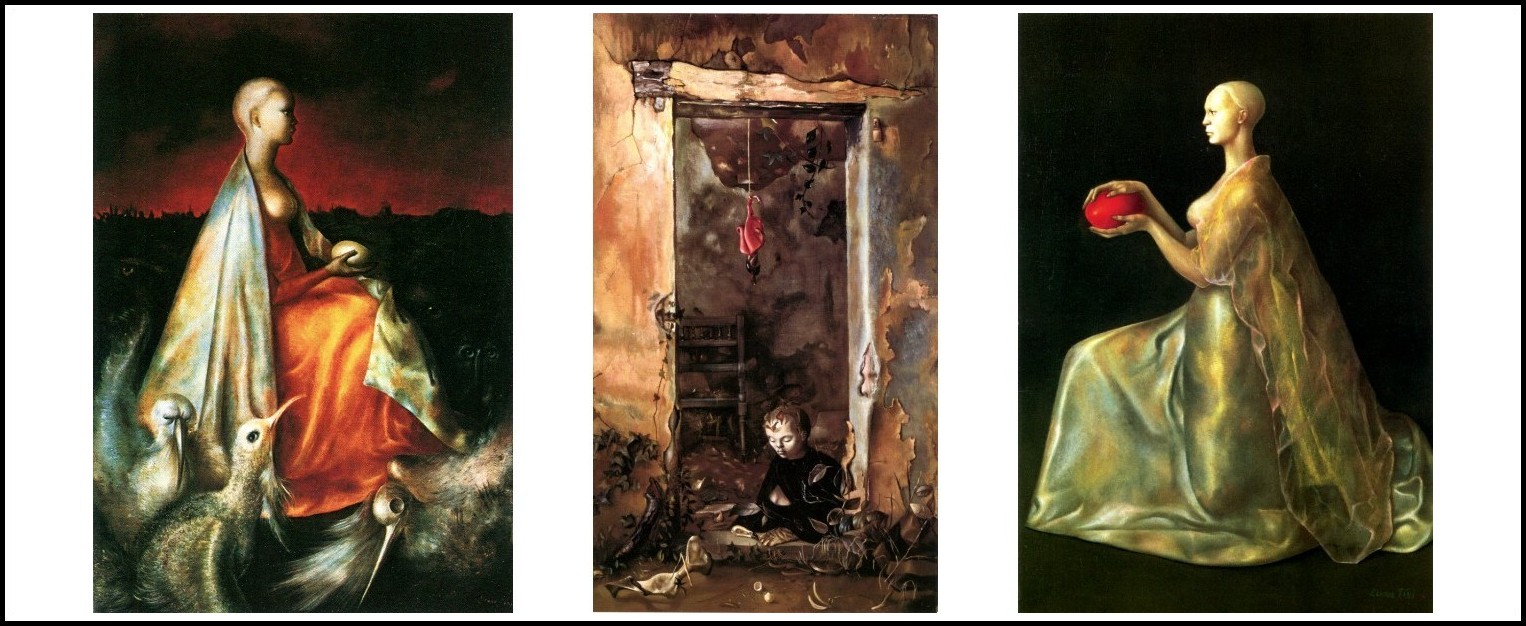

In Fini’s The Guardian of the Phoenixes and The Guardian with the Red Egg, woman presides over a secret ceremony of rebirth in which the egg becomes an essential metaphor for the creative process. But the image also appears in other paintings in contexts that may suggest aridity and desolation rather than creation. Fini’s Petit Sphinx ermite contains a guardian Sphinx, dressed in black and with eyes closed, that lies in the doorway of an abandoned and ruined building in which plaster peels from ocher walls and somber vegetation crawls over the door sill and threatens to engulf the silent watching figure. In front of the door, a pelvic bone and a broken eggshell, stripped of any sign of life, lie on the ground. The only sign of life is a fleshy pink flower suspended from above on a long string and pulsing in sinister fashion with the sense of life which is otherwise almost entirely missing from the painting.

LEONOR FINI

The Guardian of the Sphinxes, 1954 | Petit sphinx ermite, 1948 | The Guardian with the Red Egg, 1955

The egg is the name of the alchemical vessel of transmutation or the alchemist’s oven and is often used as a symbol of the female’s role as a universal vessel of creative or spiritual rebirth. But it is an image often used also by male artists in a Surrealist context, most frequently by Ernst. In his Beyond Painting, published in New York in 1948, Ernst offers some autobiographical comments concerning his origins: The second day of April (1891) at 9:45 a.m. Max Ernst had his first contact with the sensible world, when he came out of the egg which his mother had laid in an eagle’s nest and which the bird had brooded for seven years. Ernst’s mention of the number seven confirms the image’s alchemical origins, for in alchemy there are seven metals involved in the Work. Seven is also the number of planets of the universe and the macrocosm. In Carrington’s essay ‘The Bird Superior Max Ernst,’ the alchemical transformation that takes place requires seven turns; the number reappears in her short story ‘The Seventh Horse,’ in which the seventh horse is an image of transformation. For Ernst, the eye and the egg were closely related, and his series of paintings titled At the Interior of Sight: The Egg (1929) identify the forms of eye and egg as interchangeable images indicating the sources of creation as interior. Ernst’s reference is to the process of bringing the work of art into existence through a semi-automatic process of visual hallucination in which the eye is allowed to suggest images that derive their power from their mental correspondences. In The Kitchen Garden on the Eyot and other works by women artists, the image is a potent metaphor for creative life or, sometimes, for the loss of creative powers.

Max Ernst, At the Interior of Sight: The Egg, 1929

The significance of alchemy, over and above its chemical and pseudoscientific phases, lay in its identification of the true subject, the prima materia, as man. The alembic, furnace, philosophical egg, and so on in which the work of fermentation, distillation, and preparation took place was man; the alchemist Alipili explains: The highest wisdom consists in this, for man to know himself, because in him God has placed his eternal Word. Therefore let high inquirers and searchers into the deep mysteries of nature learn first to know what they have in themselves, and by the divine power within them let them first heal themselves and transmute their own souls. For Carrington and Varo, the path of spiritual evolution was woman’s. During the early 1950s both women became involved with the followers of Gurdjieff, and with Tibetan Tantric and Zen Buddhism; prior to these involvements, however, their work was already revealing a sensitivity to the idea of an evolutionary feminine consciousness and to seeking out the sources of woman’s creative impulses. Carrington’s 1948 exhibition at the Pierre Matisse Gallery in New York included a number of paintings on themes already discussed here as well as several that deal more specifically with the image of woman as a seeker after spiritual enlightenment.

Leonora Carrington | Remedios Varo

Are You Really Syrious? Refers to the dog star, Sirius, under whose ascendancy Isis brought forth her five children and which, recalled for modern readers by T. S. Eliot in ‘Sweeney Among the Nightingales,’ was associated with the flooding of the Nile and the fertility signaled by that annual event.

Leonora Carrington, Are You Really Syrious?, 1953

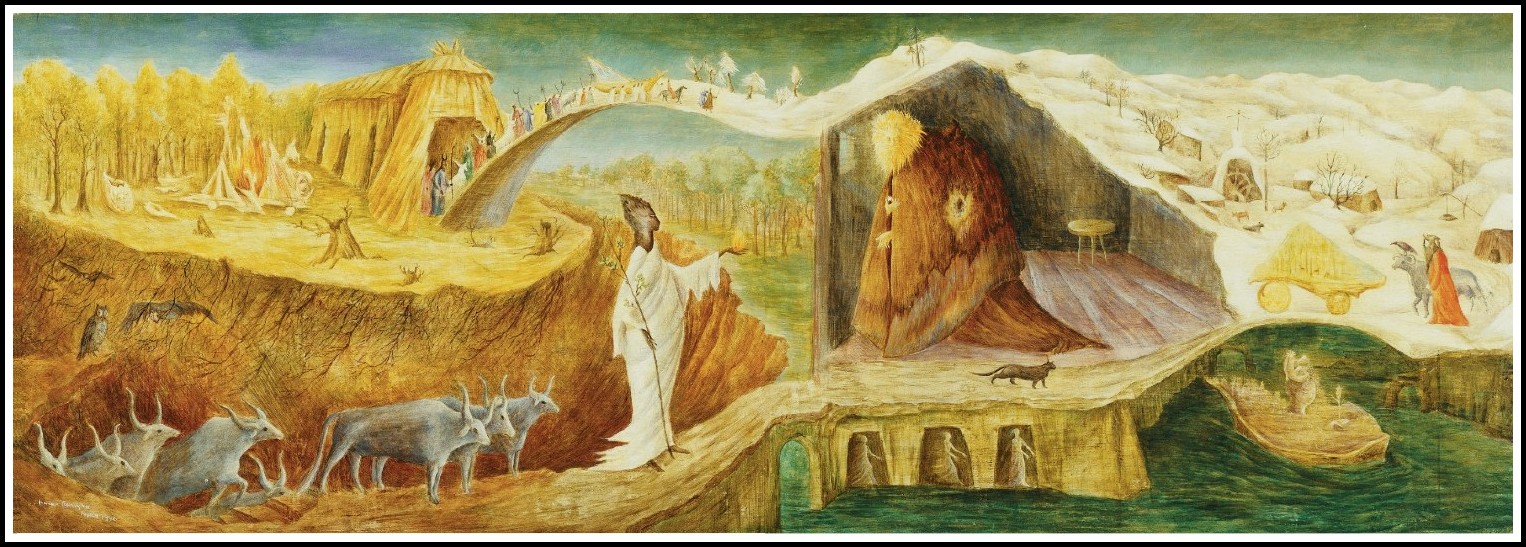

Palatine Predella, a friezelike presentation reminiscent of early Renaissance predellas with their scenes from the lives of the saints, offers simultaneous visions of several different worlds. In the middle layer of the painting, a white-robed woman ascends from a fiery underworld followed by a procession of sacred horned beasts bearing the familiar lyre-shaped horns of the goddess consort. In one hand she holds a leafy stave, in the other a flame that she offers to a bearded anchorite in a bare monastic cell. The fact that the flame does not burn her hand suggests that she has magic powers; she holds it forth as if it were a sacred flame of enlightenment, perhaps the very one that he had been seeking through prayer and fasting, but which can be revealed only by woman. Where the earth is cut away, tree roots are exposed like veins, a motif frequent in the works of Kahlo from this period. The roots trap nocturnal birds like the owl. Arching over the hermit’s cave is another landscape, this one snowy and containing another procession, beginning its ascent following a fabulous beast. Carrington’s palette fluctuates between intense reds and yellows and a deep rich green, imparting to the landscape something of a seasonal feeling. Spring-like vegetation, the deep reds and yellows of autumn, and a wintery landscape combine in a drama that reads like Proserpina’s return from the underworld, but is more likely meant to evoke the figure of the Egyptian goddess Isis.

Leonora Carrington, Palatine Predella, 1946

Carrington’s figure may not be a specific representation of this goddess, but there are a number of images in the painting that indicate references to this myth, long viewed as a parable of inner life and spiritual quest. The image of the Egyptian Isis, the goddess of the moon, sister and spouse of the moon god, Osiris, was revived during Hellenistic times as one of the mystery cults. In ancient Egypt, the Book of the Dead contained instruction in the mystery religion of Osiris. Osiris, who died and went to the underworld, was later restored to life by the power of Isis, who had wandered the earth searching for the dead god. In Palatine Predella the procession of horned cows indicates the presence of the goddess, and the snowy landscape indicates the winter season associated with her wanderings. Madame Blavatsky’s Isis Unveiled, published in 1877 and surely familiar to Carrington with her abiding interest in arcane traditions, used the goddess Isis, the goddess of magic, as an image of the Eastern origins of the sacred doctrines of the theosophists and their unending quest for spiritual purification through the progression from material reality to higher levels of awareness.

Leonora Carrington, Palatine Predella, 1946 (details)

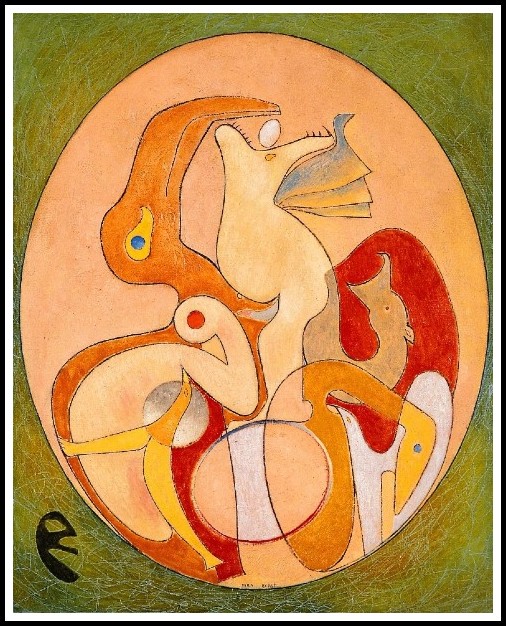

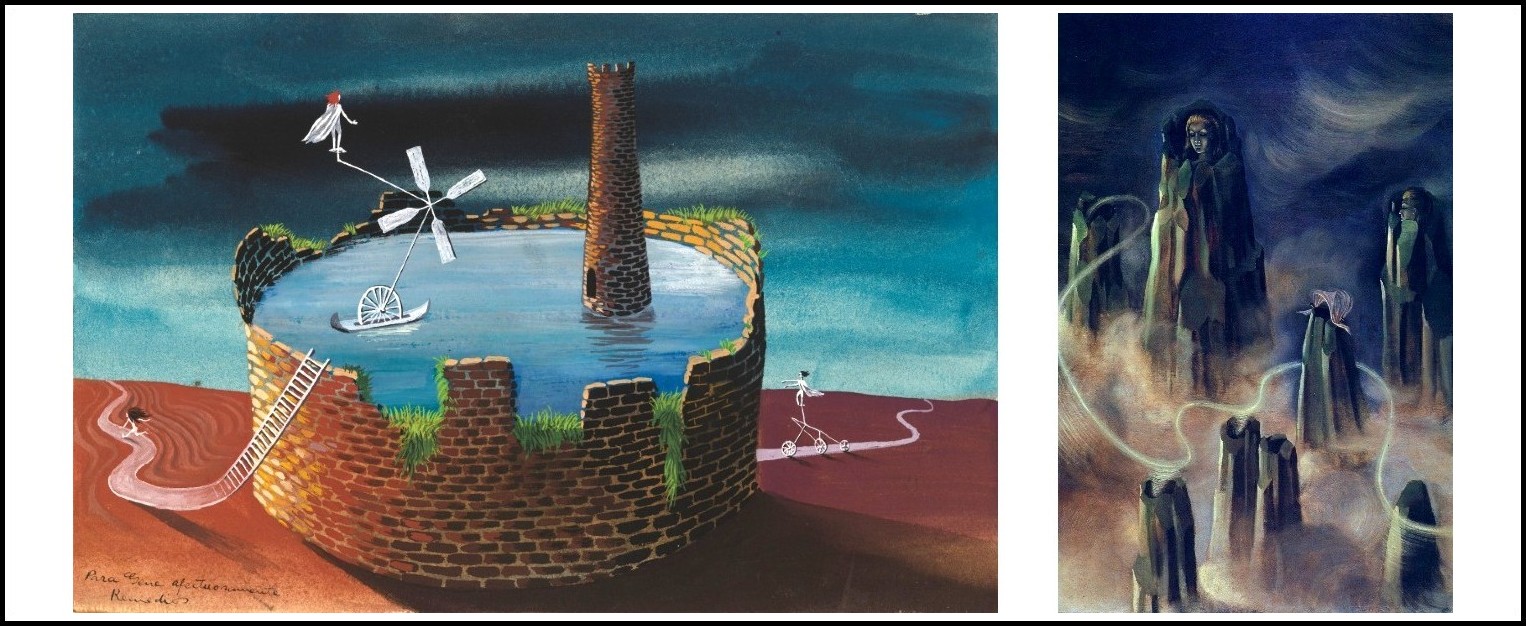

Among Varo’s early paintings is a work executed in Paris in 1938 and titled Las Almas de los Montesin which we see, above the clouds, a line of light that touches the tops of the mountains, several of which have their summits cut away to reveal female figures trapped inside in attitudes of reverie or meditation. It is as if the spirits called forth from the highest peaks are female and waiting for release from the material that binds them. In 1947, she again painted an image of woman’s journey; The Tower depicts a woman balancing precariously above a small vessel afloat in a ruined tower and searching the horizon for a land that lies ahead. Perhaps a reference to the war-torn land Varo left behind when she embarked on the final leg of her physical journey from Europe to Mexico, the painting in any case implies that land, and by implication salvation, is always ahead, out of sight.

REMEDIOS VARO

The Tower, 1947 | Las Almas de los Montes, 1938

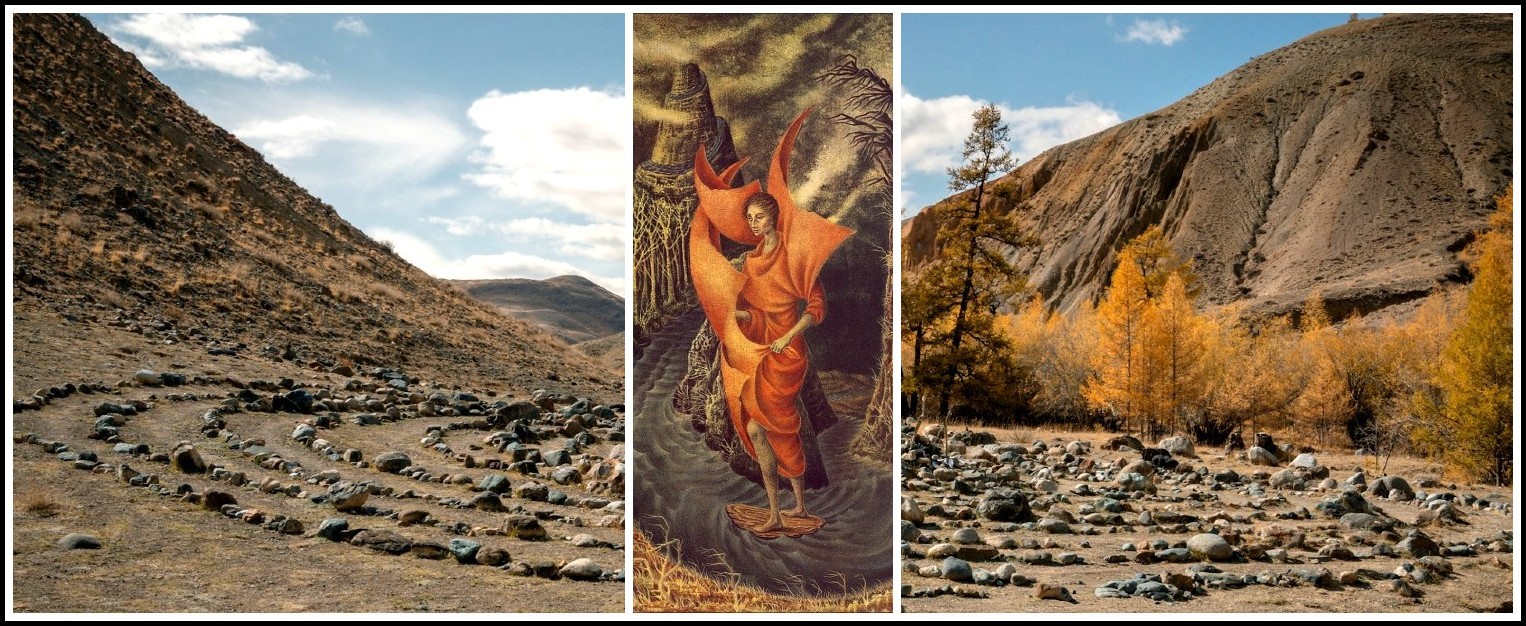

In 1960, under the influence of the followers of Gurdjieff—who believe that when an individual dies, most of the baser, coarser elements are left behind while the spirit advances to another, purer sphere—she painted Ascension of Mount Analogue. The title is taken from Rene Daumal’s unfinished novel posthumously published in 1952. Daumal, under the influence of Gurdjieff and Eastern philosophy, wrote a spiritual parable of the journey to enlightenment and spiritual purification as an expedition to Mount Analogue, a mountain the bottom of which is approachable by man, the top of which remains hidden and inaccessible. Varo chooses the spiral form of the sacred mountain, for the pilgrim, ascending in a spiral fashion, sees both what has been accomplished and what lies ahead still to conquer. Her single traveler raises the folds of his monkish habit to use them as a sail, propelled along by the wind on a tiny chip of wood that is surely too small and insubstantial to support the weight of a human, but which may well stand for the tiny crystal chips or ‘paradams’ that are the only thing valued by the guides of Mount Analogue and which may be used as currency in the ascent.

Remedios Varo, The Ascension of Mount Analogue, 1960 | Background photo: Ruslan Mingazhov, Unsplash

Such questings after spiritual essence are the stuff of which Grail literature is made. Echoes of the Holy Grail with its elixir of life are found throughout the later paintings and writings of Carrington and Varo. The image appears in Varo’s Born Again in which the figure of a naked woman with full breasts bursts through the wall into an inner sanctum where a chalice stands on a small table. Leaning over its luminous surface, she sees not her own reflection but that of the new moon.

Remedios Varo, Born Again, 1960 | Background photo: Finn Mund, Unsplash

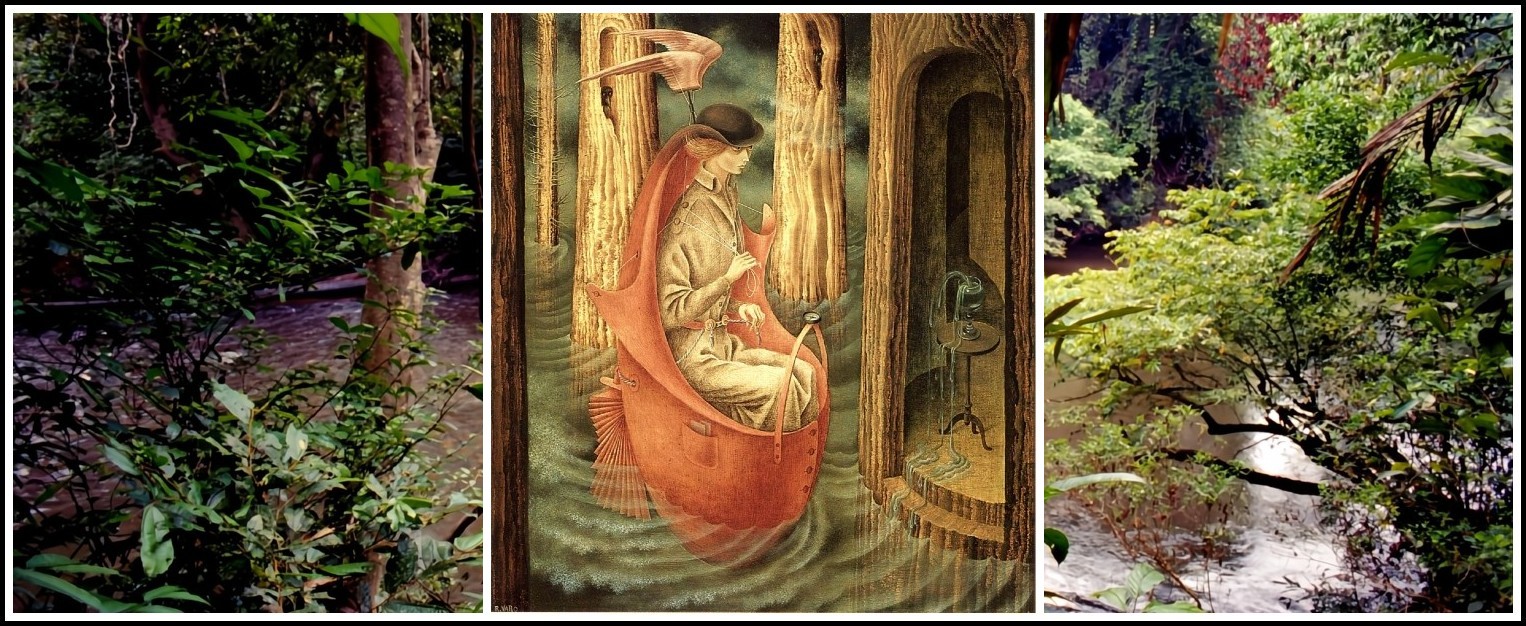

Themes of spiritual travel and enlightenment combine in paintings like Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River. In late 1947, Varo traveled to Venezuela to visit her brother. She remained for two years, during which time Péret, from whom she had grown increasingly estranged, returned to Paris. During her stay in Venezuela, she made a trip to the source of the country’s major river in search of gold and discovered that the river arose in a forest that was completely flooded during certain times of the year. That this alchemical journey was associated in Varo’s mind with the search for the Grail is suggested by her painting of the expedition. Her pictorial version shows a well-dressed female traveler manipulating the flaps of a fantastic aquatic vessel that combines aspects of her trench coat and hat as she sails along the Orinoco with silent determination. The voyage through the flooded forest brings her not to gold but to a goblet, the metaphysical source, which holds an eternal and inexhaustible jet of water.

Remedios Varo, Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River, 1959 | Background photo: Wietse Jongsma, Unsplash

The constant search for enlightenment and spiritual development, for planes of existence that more fully unified spirit and matter and that offered an escape from baser realities, propelled Varo and Carrington into a variety of occult and esoteric studies. Toward the end of her life, Varo’s search was directed toward dispelling the despair and depression that often threatened to overwhelm her. Carrington’s path led, finally, to the conscious articulation of her concerns through the feminist movement of the early 1970s. In a commentary written on the occasion of her 1976 retrospective exhibition at the Center for Inter-American Relations in New York, she, like Breton, but toward different ends, invoked the domain of Faust’s Mothers in laying claim to woman’s legendary powers: The Furies, who have a sanctuary buried many fathoms under education and brain washing, have told females that they will return, return from under the fear, shame, and finally through the crack in the prison door. I do not know of any religion that does not declare women to be feeble-minded, unclean, generally inferior creatures to males, although most humans assume that we are the cream of all species. Women, alas, but thank God, homo sapiens. Most of us, I hope, are now aware that a woman should not have to demand Rights. The Rights were there from the beginning; they must be Taken Back Again, including the mysteries which were ours and which were violated, stolen or destroyed, leaving us with the thankless hope of pleasing a male animal, probably of one’s own species.

John Singer Sargent, Orestes Pursued by the Furies, 1921 | Leonora Carrington (Photo: Kati Horner)

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE POST

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2026 | All rights reserved

Comments