Remedios Varo

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 1: Lilo

We speak of women artists, we find we share a love for Frida Kahlo, Tamara de Lempicka, Remedios Varo.

Remedios Varo, Mexico City | photo: Kati Horna

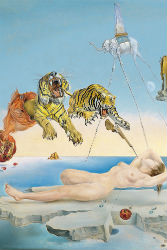

HOW TO PRODUCE EROTIC DREAMS: A RECIPE BY REMEDIOS VARO

Published posthumously (1970). From Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Jennifer Mundy, editor (London: Tate Publishing, 2001), p.306

Remedios Varo | photo: Kati Horna

Ingredients: One kilo black radishes; three white hens; one head of garlic; four kilos honey; one mirror; two calf’s livers; one red brick; two clothespins; one whalebone corset; two false moustaches; two hats of your choice.

Pluck the hens, carefully setting aside the feathers. Boil in two quarts of unsalted distilled water or rainwater, along with the peeled, crushed garlic. Simmer on a low fire. While simmering, position the bed northwest to southeast and let it rest by an open window. After half an hour, close the window and place the red brick under the left leg at the head of the bed, which must face northwest, and let it rest.

While the bed rests, grate the black radishes directly over the consommé, taking special care to allow your hands to absorb the steam. Mix well and simmer. With a spatula, spread the four kilos of honey on the bedsheets and sprinkle the chicken feathers on the honey-smeared sheets. Now, make the bed carefully.

The feathers do not all have to be white — they can be any colour, but be sure you avoid Guinea hen feathers, which sometimes provoke a state of prolonged nymphomania, or dangerous cases of priapism.

Put on corset, tighten well, and sit in front of the mirror. To relax your nerves, smile and try on the moustaches and hats, whichever you prefer (three-cornered Napoleonic, cardinal’s hat, lace cap, Basque beret, etc.).

Put the two clothes pins on a saucer and set it near the bed. Warm the calf’s livers in a water bath, but be careful not to boil. Use the warm livers in place of a pillow (in cases of masochism) or on both sides of the bed, within reach (in cases of sadism).

Remedios Varo | photo: Walter Gruen

Remedios Varo | photo: Walter Gruen

From this moment on, everything must be done very quickly, to keep the livers from getting cold. Run and pour the broth (which should have a certain consistency) into a cup. As quickly as possible, return with it to the mirror, smile, take a sip of broth, try on one of the moustaches, take another sip, try on a hat, drink, try on everything, taking sips in between. Do all this as rapidly as you possibly can.

When you have consumed all the broth, run to the bed and jump between the prepared sheets, quickly take the clothes pins and put one on each big toe. These clothes pins must be worn all night, firmly pressed to the nails, at an angle from the toes.

This simple recipe guarantees good results, and normal people can proceed pleasantly from a kiss to strangulation, from rape to incest, etc., etc.

Recipes for more complicated cases, such as necrophilia, autophagia, tauromachia, alpinism and others, can be found in a special volume in our collection of ‘Discreetly Healthy Advice’.

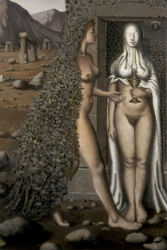

JENNIFER MUNDY ON REMEDIOS VARO’S ‘WOMAN LEAVING THE PSYCHOANALYST’

From Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Jennifer Mundy, editor (London: Tate Publishing, 2001), p.306

Often known, like many surrealist women painters, simply by her first name, Remedios Varo met the surrealist Benjamin Péret in Madrid in 1936. She went with him to Paris where from 1937 to 1942 they were both members of the surrealist group. In a later interview she recalled, ‘Yes, I attended those meetings where they talked a lot and one learned various things. My position was the timid and humble one of a listener; I was not old enough nor did I have the aplomb to face up to them, to a Paul Eluard, a Benjamin Péret, or an André Breton. There I was with my mouth gaping open within this group of brilliant and gifted people.’ During the Nazi occupation of France she and Péret escaped to Mexico, where they were active in the surrealist community that included Leonora Carrington and the poet Octavio Paz. They separated and Péret returned to Paris in 1947.

In Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst Varo cloaks the pseudo-science of psychoanalysis in a medieval setting, with the initials of its three fathers inscribed on the portal behind the central figure, ‘FJA’ standing for Freud, Jung and Adler. Varo uses the various associations of the veil to invoke seduction (Salome) and the idea of stripping to reach psychological or metaphysical truths. The woman is shrouded in a garment, which contains within it a mask, but her face is partly uncovered. Without a trace of hesitation or compunction, she drops a male disembodied head (Varo’s father’s? or, more likely, Péret’s?) down a well, which, Varo wrote, was ‘the proper thing to do when leaving the psychoanalyst’.

Remedios Varo, Woman Leaving the Psychoanalyst, 1960

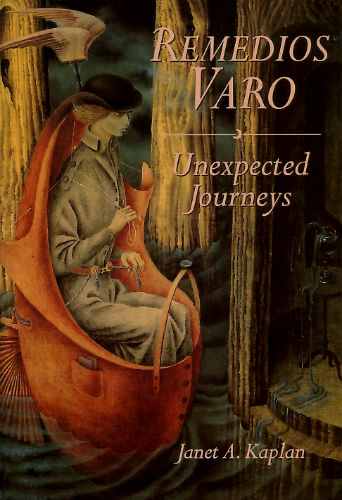

JANET ANN KAPLAN ON REMEDIOS VARO

Janet Ann Kaplan (1945-2014) was Professor of Art History and Director of Curatorial Studies at Moore College of Art and Design (Philadelphia).

Her book, Remedios Varo: Unexpected Journeys (now out of print) is a very fine study of the artist.

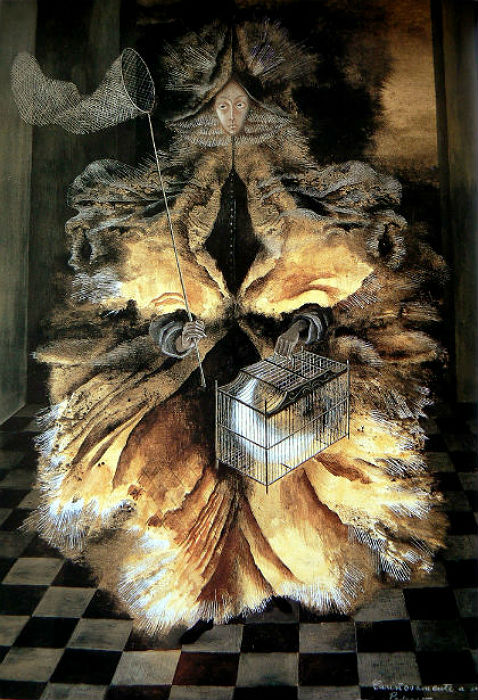

Remedios Varo, Star Catcher, 1956

An image of the moon entrapped is seen in Varo’s Star Catcher, in which a fantastic huntress has captured the moon and carries it in a cage. Dressed in an exquisite costume with delicately marked butterfly-wing sleeves, she holds the butterfly net with which she caught the glowing crescent. Related to Diana the huntress—goddess of the moon and protectress of women—she has snared an archetypal symbol of feminine consciousness, but her purpose remains unclear. This painting, among Varo’s most beautiful, is iconographically ambiguous. The image of an imprisoned moon is disturbing; it reinforces the feelings of constraint and enclosure that fill so many of Varo’s works. The tension between the strength of the butterfly huntress and the weakness of the caged moon exemplifies the subtle interplay between powerlessness and power that was a recurring theme for Varo.

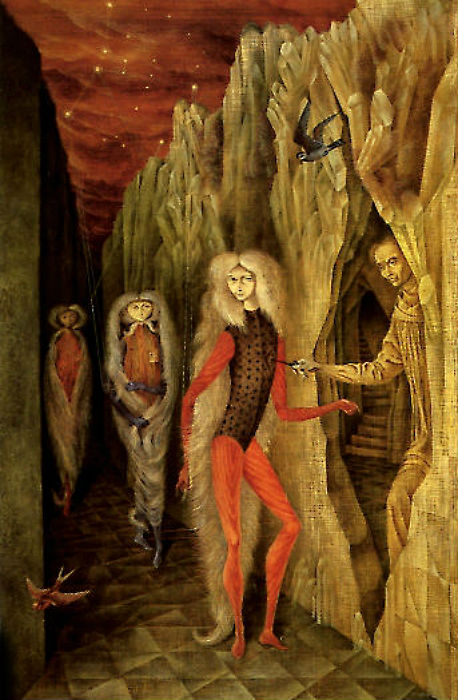

Varo transformed traditionally male mythic heroes into female form, creating, for example, a female Minotaur who holds a magical key before a mysterious floating keyhole. Although many of the characters in Varo’s paintings are androgynous or asexual, in these mythological transformations she was careful to delineate the female anatomy of her heroines.

Varo was not alone in exploring such symbols and transformations. In work by many of the women associated with the Surrealist movement there are references to women’s secret wisdom and special creative powers. This centrality of woman as a creative agent developed in seeming reaction to official Surrealist doctrine, which defined woman as muse and as object of male desire. The self-referential nature of work by the women Surrealists is most clearly apparent in the repeated self-portrait characters who (like those that bear Varo’s features) signal the artists’ intense quest for personal definition. Absorption with self-analysis is found throughout their work, explored in a series of narrative fantasies, not only in painting and sculpture but in writing as well.

Remedios Varo, Minotaur, 1959

Remedios Varo, Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River, 1959

The intrepid traveler in Exploration of the Sources of the Orinoco River is a most determined woman who bears particular resemblance to Varo herself. A courageous heroine, she has set out on a solitary journey to find ‘the source.’ Although she is dressed in a marvelously adapted English trench coat and bowler hat, carrying wings overhead that seem to have been borrowed from a theatrical production, the seriousness of her purpose is not compromised. The playfulness of her vehicle—a waistcoat transformed into a fragile little ship with notes in the side pocket and a compass instead of a watch fob—does not negate the intensity of her expression nor the somber watchfulness of the dark birds that attend her from the hollows of nearby trees. What she confronts is a simple wineglass, set on a modest table in a hollowed-out tree. A magical liquid flows out of the goblet, becoming the source of the river on which she travels.

This painting exemplifies the multiple levels of association that cohere in Varo’s imagery—oneiric, autobiographical, occult. The waistcoat boat and flooded woods are wonderfully evocative, dreamlike images of subconscious travel. They also reflect Varo’s real travels in Venezuela to the site of forests flooded by the Orinoco River, where her friends had joined an expedition in search of gold. But the goblet (or Grail) with its inexhaustible flow of holy elixir also locates the scene within ancient mythic traditions. Thus the search of this woman can be understood on a spiritual level, the gold being philosopher’s gold, the alchemical liquid of transformation. Just as alchemy is both a scientific study and a mystical search, so Varo used exploration of the river’s source as a metaphor for the spiritual quest. This painting also exemplifies the contradictions inherent in much of Varo’s work: no matter how intrepid, her travelers are rarely if ever free. Here the traveling outfit, while a wonderfully inventive means of transport, acts also as a form of restraint, binding the woman into her boat with an elaborate network of interlaced cords.

In Caravan, Varo continued in the personal vein already begun in The Tower, building fantasy around autobiography. In this image a house on wheels, with pulleys and propellers, is peddled by a mysterious cloaked man who steers the curious vehicle through a lushly wooded landscape. Inside the house—which is filled with doorways and windows, each oriented toward a different direction—sits a woman at a piano. As Varo described it, ‘This caravan represents a true and harmonious home, inside of which there are all perspectives, and happily it goes from here to there, the man guiding it, the woman tranquilly making music’. This can be understood as a metaphor for Varo’s new-found security. Here, the woman, a musician, is safely inside an interior that radiates warmth, freed to concentrate on her art by the man who is outside, bundled up against the elements, guiding the progress of their home. The house travels ‘happily,’ the woman works ‘tranquilly,’ all expressions of the ease that Varo was now enjoying.

This use of fantastic vehicles as emblems for her personal dislocation had been a theme of her earlier work as well. The isolation of this vehicle, alone in a deep and misty woods, is reinforced by the isolation of the figures themselves—she inside, he out, facing away from each other and totally absorbed in separate activities. This theme of human isolation is one that Varo continued to explore: it is rare to find people in direct contact with one another in her work.

Remedios Varo, Caravan, 1955

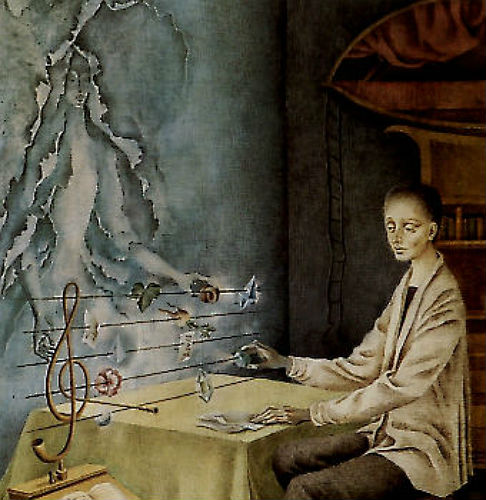

Remedios Varo, Creation of the Birds, 1957

The painting most revealing of that magic of interconnection is Varo’s Creation of the Birds. Here a scientist-artist in the persona of Wisdom—the owl—sits at a desk drawing a bird. Using primary colors distilled from the atmosphere, she draws with a pen that is connected through a violin to her heart. Moonlight (the domain of both owl and woman), captured and magnified through a triangular lens, illuminates the drawing, stimulating the drawn birds to come to life and take flight out a window. In this reversal of the Annunciation, the bird does not announce new life; it embodies new life. Here is the true interconnection of art, science, alchemy and nature, each nurturing the other in a cycle symbolically represented by the two vases in the corner, which feed their golden contents back and forth to each other. Varo’s choice of symbols is significant. She used an egg-shaped alchemical vessel as the receptacle of transformation, in which is created the palette of primaries, the trinity that is the foundation of all color in art. She chose a triangular magnifier, like the triangular prism that Newton, the master scientist, had used to separate light into the colors of the spectrum. By creating birds that fly off the page, Varo placed herself within the tradition of mythological artists such as Pygmalion, whose creation was said to have come to life, and Daedalus, who sculpted wings that offered flight.

In aligning herself with these traditions, Varo made a claim for the artist as one who goes beyond mere imitation of nature to actual creation itself. This painting of the owl-woman-artist-alchemist creating beauty and life through the conjunction of color, light, sound, science, art, and magic is the very image of creativity to which Varo aspired in her life. As creativity and harmony are at the center of this painting, so they were at the very core of Varo’s being. Thus, Creation of the Birds can be seen as the paradigmatic image of the fulfillment of her quest.

Varo repeatedly turned to music as a symbol of the wholeness she sought. In Harmony, she created the world of the composer, a quiet, dark, fecund world of diligent study. An androgynous figure whose features mirror Varo’s own sits in a medieval-looking study filled with the tools of the alchemist. Taking objects from a treasure chest—geometric solids, jewels, plants, crystals, handwritten formulas — the composer places them as notes onto a three-dimensional musical staff, creating from a chaos of possibilities the order that is music. Varo: ‘The person is trying to find the invisible thread that links everything and, for this reason, is skewering all kinds of things on a staff of metal threads’. Like Pythagoras searching for the secret harmony between music, nature, and mathematics, the composer looks to unite the abstract and the concrete with the intangibility of sound. Varo: ‘When he has succeeded in putting each of the diverse objects in its place, by blowing through the clef that supports the staff, a music should come out that is harmonious’. It is the breath of the musician, through the magical process of ‘inspiration,’ that sets up the vibrations of musical harmony.

Remedios Varo, Harmony, 1956 (detail)

Remedios Varo, Troubadour, 1959

Like Hieronymus Bosch, Varo stayed close to nature, sharpening the comic edge of her bizarre combinations by the careful rendering of obsessively specific details. In Troubador, she depicted a variety of identifiable species of birds, oversize in comparison to their human companions, much like the naturalistically rendered birds in Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights.

Her 1956 solo exhibition had established Varo as a self-supporting artist who could sell whatever she wanted to paint. Yet in 1957, although she profoundly disliked making portraits, she took on commissions from two prominent Mexican families to paint portraits of their children.

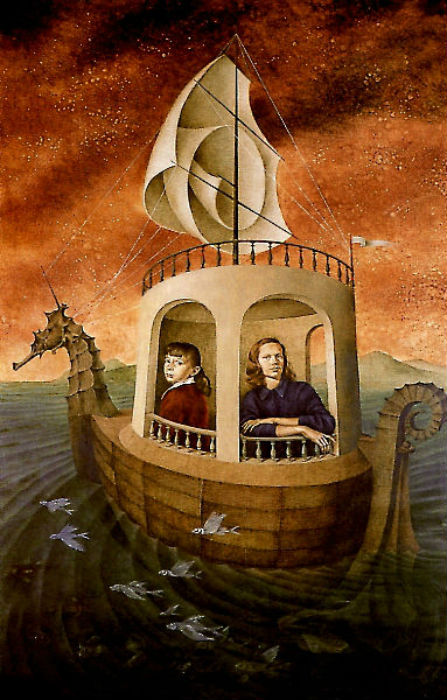

In Daughters of the Arnus Family, Varo depicted two girls, one a preteen, the other an adolescent, as oversize figures in an elaborate seahorse boat. Gazing out apprehensively, the girls seem uncomfortably cramped, especially in contrast to the school of flying fish that darts beside the boat in the open air and water.

Remedios Varo, Daughters of the Arnus Family, 1957

Remedios Varo, Personage, 1958

While still in Madrid, Varo likely encountered Goya’s A Way of Flying and They Have Flown in which a woman in traditional Spanish costume with butterfly wings atop her head also flies through the air, using her black mantilla as a giant webbed wing. Editions of Goya’s graphics would have been available to Varo at the Academia de San Fernando, which first published Goya’s Disparates in 1864. These two particular works by Goya might have received special notice because they were part of a series of Spanish airmail stamps based on Goya’s flying subjects that were first issued in 1930, while Varo was still a student.

Both Goya and Varo also invented hybrid creatures capable of flight. Goya created a curious figure with bat-wing ears and taloned feet. Varo showed a woodland creature, her Personage, with a woman’s body, insect wings, rabbit ears, and antelope horns, running lightly through a forest as though about to lift off the ground. Both their creatures seem disturbingly human, despite their animal parts.

Similarities in motif notwithstanding, Varo’s work differs from Goya’s in several ways. She did not depict horror; there is no overt violence in her work. Her characters, though fanciful, are neither demonic nor scary. In fact, she seems to have carefully avoided many of Goya’s favorite subjects: bullfights, war, torture, pain, and death. Hers is not the ‘black’ imagery so commonly associated with Spain, especially Goya’s Spain. There are differences in style as well. Goya’s work is loose and sketchy, emphasizing gradation of tone more than detail or line. Varo, on the other hand, filled her work with minute detail, making her settings far more specific than Goya’s.

In Hairy Locomotion, danger is realized as a girl is kidnapped by a man lurking high above the street, who extends his long beard down around the corner to snatch her up as she passes. Three other men, identified in Varo’s notes as detectives dispatched to investigate the crime, are ludicrously ineffectual, hovering above the ground with their heads lost in clouds that look oddly like the fur hats worn by Hasidic Jews. Their beards, elongated and stiffened, have become the wheels on which they ride. For steering they use their handlebar mustaches, which have similarly lengthened and stiffened to cleverly serve the purpose stated by their name. The kidnapped girl, strikingly similar to the young Remedios, is not at all amused. The tension in her rigid body expresses her anxiety and is set against the inventive humor that Varo often used to mitigate the pain.

Remedios Varo, Hairy Locomotion, 1959

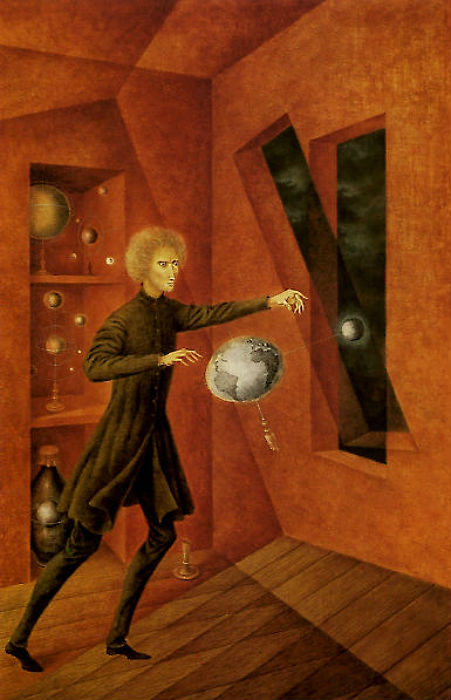

Remedios Varo, Penomenon of Weightlessness, 1963

Phenomenon of Weightlessness portrays a scientist who is awakened to an entirely new order of experience. An astronomer stands astonished as the earth and its moon, represented as a globe on a stand, escape from the force of gravity and float into another dimension, a plane of space tilting at an angle to the room. The scientist has good reason to be surprised. He had kept everything neatly arranged, with various models of the solar system safely tucked away on his laboratory shelves. Now this model has broken loose and disrupted the order he had worked so carefully to maintain. Disoriented, trying to catch the floating orbs, he must also struggle to maintain his own balance as he finds himself with his left foot in one spatial dimension and his right foot in the other.

The scientist in the painting is depicted as overwhelmed, pushed (quite literally) toward new ways of thinking by forces beyond his control. He had based his models on the theories of Newton, on the idea of a universal law of gravitation, constant and unchanging. This vision was supplanted by Einstein’s theory of relativity, a theory not of constancy but of change. As Einstein had theorized that ‘the gravitational field near the sun could cause a glancing ray of light to bend inwards—like distortion of space,’ so the astronomer here must recover his balance after just such a bending inward of the space within his room. The astronomer yields to this vision, perhaps reluctantly, and establishes new footing. In so doing, he, too, confirms that scientific truth itself is relative and that any one interpretation, no matter how neatly it fits on the shelves, must remain open to leaps of imagination that will produce totally different formulations.

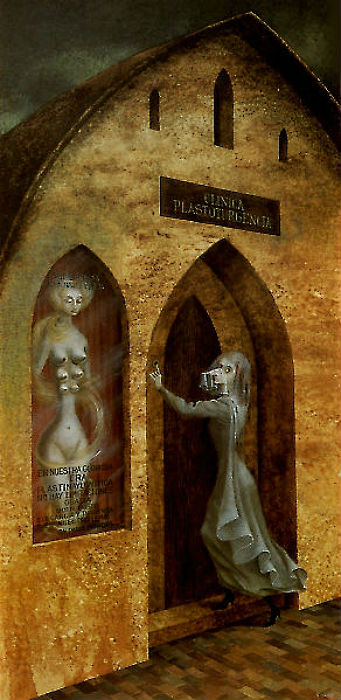

In Visit to the Plastic Surgeon, the veil is turned to a humorous purpose, serving as a diaphanous shield for the lengthy proboscis of a woman who surreptitiously rings the bell of a clinic in search of surgical help. As if to inspire confidence, the clinic window displays the doctor’s latest creation, a woman whose body has been modified by the addition of two extra sets of breasts. Dr. Jaime Asch, a Mexican plastic surgeon for whom this parody was painted, remembers endless discussions, only half in jest, in which Varo worried about the length of her nose and debated the potential benefits of cosmetic surgery.

Remedios Varo, Visit to the Plastic Surgeon, 1960

Remedios Varo, Lovers, 1963

Varo also presented the bonds of love as an impediment to true autonomy. Having deferred her artistic development to the demands of several love affairs, she had reason to understand that such relationships could block personal fulfillment. In The Lovers, she depicted a couple holding hands, lost in each other’s gaze. The partners’ heads have been replaced by mirrors, so that what they see is not each other but reflections of themselves. The power of this narcissistic attraction is so great that it generates steam that rises, condenses, and falls back down as rain, creating a flood that swirls around their legs. If they do not break out of their stuporous adoration, they will surely drown. Although this is a rare instance in Varo’s work of loving contact between two people, she mocks such personal attachments as a potential source of doom.

For a portrait commission, Varo painted the prominent Mexican cardiologist Dr. Ignacio Chavez. Depicting the doctor as a kind of Svengalian figure, she dressed him ‘in somewhat priestly clothing to suggest that this profession is perhaps a kind of priesthood. In his hand he holds a key. The persons coming from the gorge have a little door in place of a heart and he winds them up as they pass by.’ In this comment on medicine’s godlike pretensions, Varo also derided the mindless way that patients, here little more than puppets, allow ‘authorities’ so much control.

These were far from traditional portraits, but Varo’s patrons must have expected something out of the ordinary in choosing her for their commissions. Even so, she did not enjoy the pressure of patrons’ expectations and soon began turning commissions down or conniving ways to drive them away. She much preferred to paint fantasy portraits of people she could invent herself.

Remedios Varo, Portrait of Dr. Ignacio Chavez, 1956

Remedios Varo, Vagabond, 1957

True independence is difficult to achieve, as Varo made clear in Vagabond. Here, she depicted a man wearing an elaborate outfit that he thinks will guarantee his complete autonomy as he journeys alone on his winding path. Because he carries with him everything he needs, he feels fully self-sufficient. But, as Varo pointed out in a wonderfully detailed description, such independence is illusory:

‘I think this painting is one of the best I have done. It is a design for a vagabond’s clothes, but it is for an unliberated vagabond. It is a very practical and comfortable set of clothes that has front-wheel drive for locomotion; if he lifts his walking stick he stops. The outfit can be hermetically sealed at night and has a little door which can be locked with a key. Some parts of the outfit are made of wood, but as I said, the man is not liberated: on one side of the outfit there is a nook which acts as a living room. Here there is a portrait hanging and three books. On his breast he wears a flower pot with a rose growing in it, a finer and more delicate plant than those he finds in these woods. But he needs the portrait, the rose (nostalgia for a little garden in a house) and his cat; he is not truly free.’

Perhaps the vagabond is emblematic of Varo herself. Although she left France for Mexico with only what she could carry, she, too, found it difficult to free herself from the past.

In Breaking the Vicious Circle, the heroine seizes control and breaks free from passivity and restraint. With eyes wide and staring, as in a trance, she summons her strength to pull apart the rope that encircles her body. Electrified, her hair stands on end, charged by the energy of her act. As the ‘vicious circle’ is broken, a dense, green forest is revealed within her chest, the deep dwelling place of her unconscious, now made accessible. Accompanied by a bird, a Jungian symbol of transcendence, which nestles in the folds of the cloak at her feet, she has made a spiritual breakthrough.

Remedios Varo, Breaking the Vicious Circle, 1962

REMEDIOS VARO: THREE BOOKS

Remedios Varo, Janet A. Kaplan

Surrealism: Desire Unbound, Tate

Remedios Varo, Letters, Dreams & Other Writings

HOMAGE TO JANET ANN KAPLAN BY WAY OF RILKE AND GEORGE STEINER

Richard Jonathan

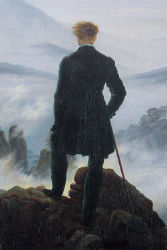

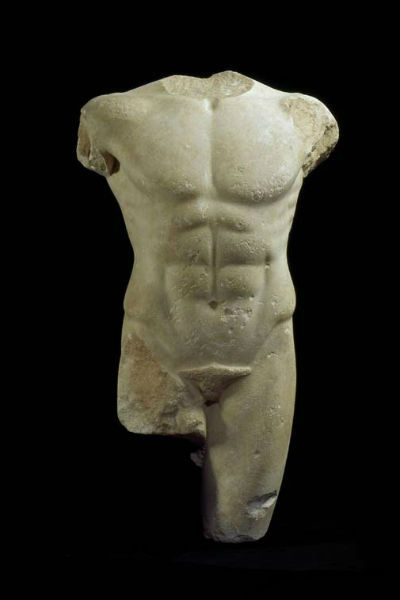

Miletus Torso (5th-4th c. BC) | Musée du Louvre

TORSO OF AN ARCHAIC APOLLO

Rainer Maria Rilke

Never will we know his fabulous head

where the eyes’ apples slowly ripened. Yet

his torso glows: a candelabrum set

before his gaze which is pushed back and hid,

restrained and shining. Else the curving breast

could not thus blind you, nor through the soft turn

of the loins could this smile easily have passed

into the bright groin where the genitals burned.

Else stood this stone a fragment and defaced,

with lucent body from the shoulders falling,

too short, not gleaming like a lion’s fell;

nor would this star have shaken the shackles off,

bursting with light, until there is no place

that does not see you. You must change your life.

From Rilke, Selected Poems (U. California Press, 1957).

Translated by C. F. MacIntyre

GEORGE STEINER, ‘REAL PRESENCES’

The archaic torso in Rilke’s famous poem says to us: ‘change your life’. So do any poem, novel, play, painting, musical composition worth meeting. The voice of intelligible form, of the needs of direct address from which such form springs, asks: ‘What do you feel, what do you think of the possibilities of life, of the alternative shapes of being which are implicit in your experience of me, in our encounter?’ The indiscretion of serious art and literature and music is total. It queries the last privacies of our existence. This interrogation is no abstract dialectic. It purposes change. Early Greek thought identified the Muses with the arts and wonder of persuasion. As the act of the poet is met, as it enters the precincts—spatial and temporal, mental and physical—of our being, it brings with it a radical calling towards change.

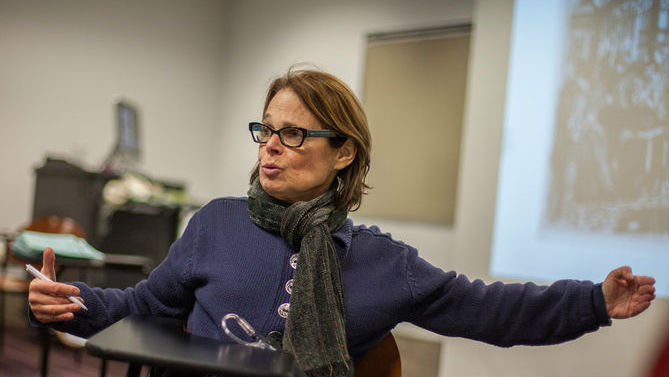

Janet Ann Kaplan teaching at Moore College of Art and Design (Philadelphia)

Janet Ann Kaplan

The waking, the enrichment, the complication, the darkening, the unsettling of sensibility and understanding which follow on our experience of art are incipient with action. Form is the root of performance. In a wholly fundamental, pragmatic sense, the poem, the statue, the sonata are not so much read, viewed or heard as they are lived. The encounter with the aesthetic is, together with certain modes of religious and of metaphysical experience, the most ‘ingressive’, transformative summons available to human experiencing. The shorthand image is that of an Annunciation, of ‘a terrible beauty’ or gravity breaking into the small house of our cautionary being. If we have heard rightly the wing-beat and provocation of that visit, the house is no longer habitable in quite the same way as it was before. A mastering intrusion has shifted the light.