The Art of Fiction, Today and Yesterday

ANTHONY BURGESS ON THE NOVEL: AN INTERVIEW

Pierre Joannon

From ‘The Sense of an Audience’ in Earl G. Ingersoll & Mary C. Ingersoll, editors, Conversations with Anthony Burgess (Jackson: University of Mississippi Press, 2008 (pp. 135-142). Interview conducted by Pierre Joannon on 9 January 1984. First published in Fabula, vol. 3, March 1984. Intertitles added by Richard Jonathan.

Bust of Anthony Burgess by Milton Hebald | House of Anthony Burgess in Bracciano, Italy | Photos: The International Anthony Burgess Foundation

I. A PROFESSIONAL WRITER

You are a professional writer. What does that term mean to you?

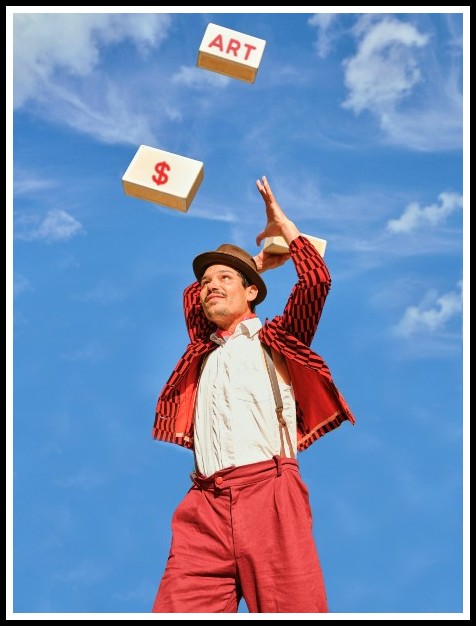

Well, it is a matter of juggling with two balls. You have to earn a living with the fiction you write. This means I have to pay the rent, to look after my wife and son. I have to live. This means I cannot practice novels in the manner of Nathalie Sarraute or Robbe-Grillet. I dare not experiment too much. I dare not appeal to too small an audience. So I have to juggle between pleasing an audience and, at the same time, pleasing myself. This is the difficulty. Writing a novel, professionally, can be a matter of producing an artifact to a formula which will make a lot of money, or else, it can be producing a work of literature, an aesthetic artifact which at the same time will sell enough copies to enable you to live. I feel that I cannot be as bold or audacious as the French anti-romanciers are, because I cannot afford to appeal to a very small audience. At the same time I cannot afford to appeal to a very large audience, because that will kill any artistic integrity I have, so I manage to balance the two balls, the ball of commercial viability and the ball of aesthetic viability, and the problem is keeping the two balls going. I have managed to do this for some years and I think that now I shall be able to carry on doing that, but one cannot forget that the novel is the primary commercial literary form that we have. I think Balzac would agree with me there. Hugo too. Flaubert to some extent. But there are several novelists in France who regard the novel as a very rarefied form which they don’t practice commercially. I practice the novel commercially.

Art vs. Commerce | Roberta Sant’Anna, Unsplash

II. CHARACTER

You speak of the novel as a relatively stable thing, with its past, its present, but you don’t seem to be concerned about the novel as a form of expression in the future.

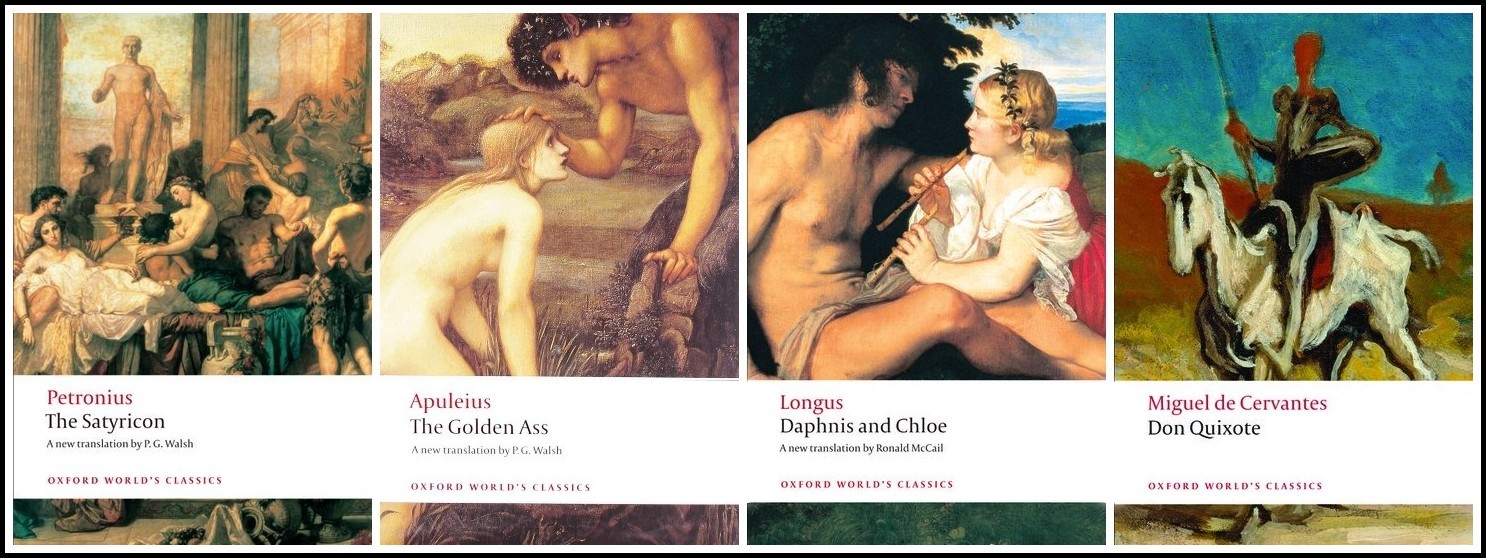

I think—and I am probably very orthodox here—that the past, the present, and the future of the novel find a common element in the fact of character. Here I travel very dangerous ground because the whole point of the nouveau roman, the anti-roman, was that character, the personnage, was a bourgeois concept essentially false. When the anti-roman began, it was saying in effect that once you rid fiction of character, what you are producing is ‘anti-fiction.’ Therefore, I assume that the basis of fiction is character. Even with an avant-garde novel like Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, the strength of the novel does not lie in experiment or the use of language; it lies in the existence of certain characters. This is also true of Ulysses. Leopold Bloom is so solid a character that Joyce can do anything, he can turn him upside-down, he can make him speak Anglo-Saxon. I think the strength of the novel lies in this solidity of character. It goes back to the Satyricon, to the Golden Ass, Daphnis and Chloe, Don Quixote. All the way through to the present time, the strength of the novel has been characters. I take it that this must be the strength of the novel in the future—not language, not ideas, not new formulations, but character, character, character.

Petronius, The Satyricon | Apuleius, The Golden Ass | Longus, Daphnis and Chloe | Cervantes, Don Quixote

III. STRUCTURE

Regarding the novel, there are other means of communication. In your opinion, what are the relationships between the novel and these other means of communication? You have a particular relationship with music. How do you balance your role as a novelist and that interest in music as an art?

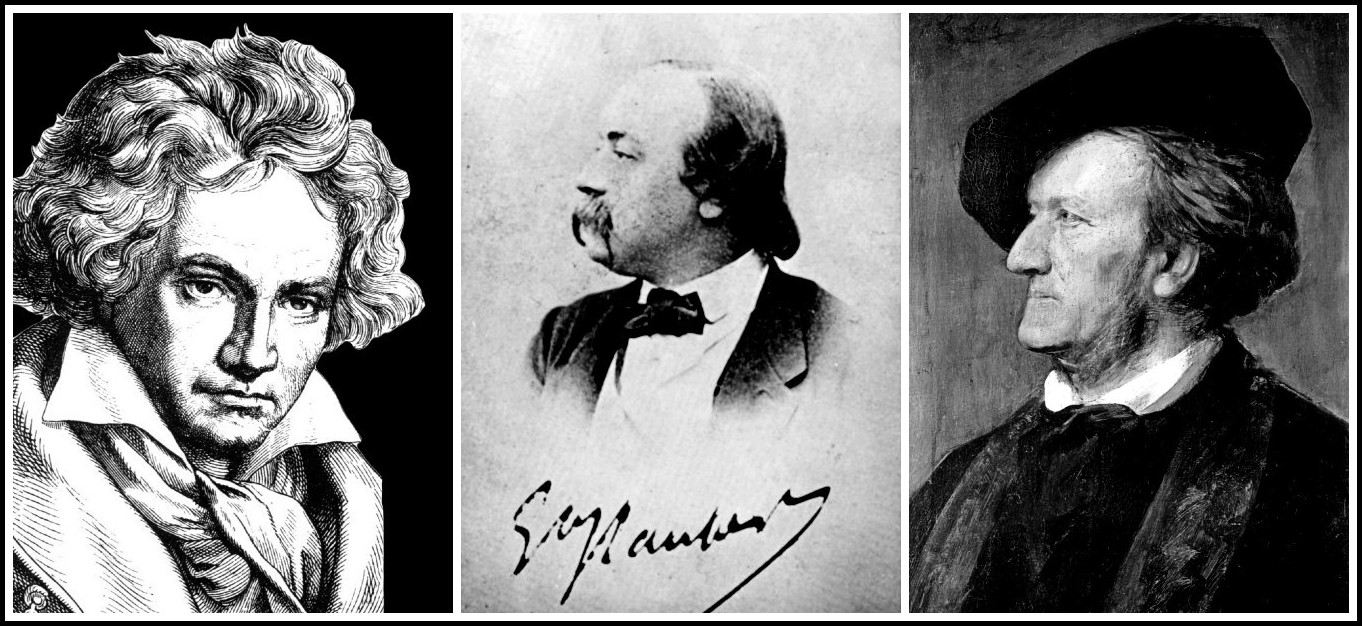

Yes, of course. One of the reasons why I thought that the practice of musical composition was comparatively limited was because, whatever we say about music, it is divorced from life. We talk about the humanity of Beethoven, the eroticism of Wagner, and so on. But the music is notes, music is sound, music is structure. The reason why I turned from musical composition to the composition of novels was that I wanted real life, I wanted to represent real life. I wanted the smell of life, the taste of life and, more than that, I wanted people. I do feel however that music and fiction have a lot in common. What they have in common primarily is the exploitation of sound. Joyce saw this very clearly. Joyce was a musician himself. The novel is a world of sound. It is the world of what people are saying, the sounds they hear. It is also a world of structure. What we can learn from music is something about the importance of structure. This was realized, I think, very clearly by Flaubert, not quite so much by Balzac to whom life was tranches de vie, slices of life. But with Flaubert, the shape of the novel was important. We are not getting life, not getting chunks of life, but life shaped into a structure. This is something that you find in music. I feel that a well-structured novel should be like a symphony: it should have a beginning and it should have an end; it should have time-axes.

Beethoven | Flaubert | Wagner

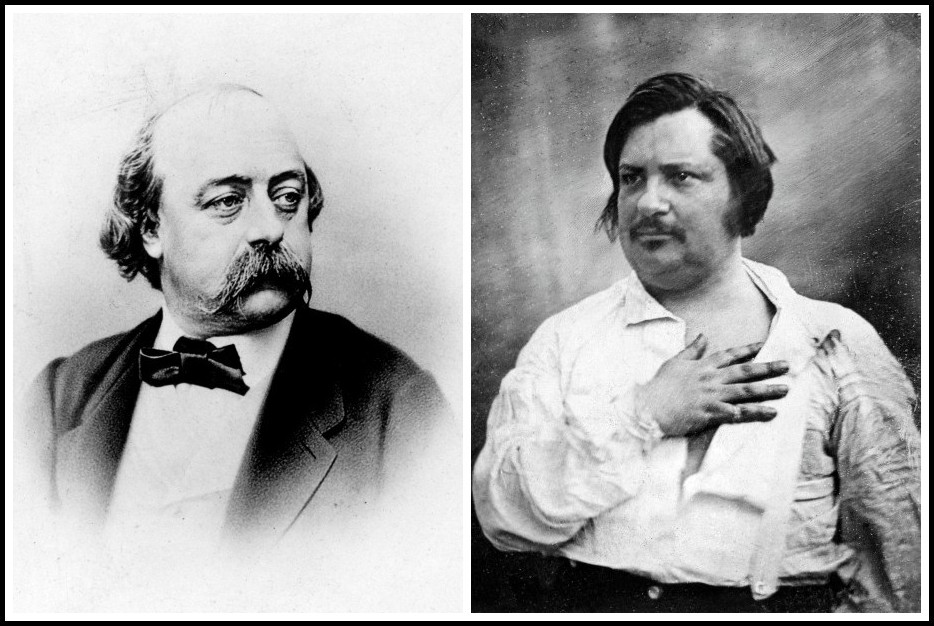

I find that having studied music and practiced it, this knowledge is invaluable to me as a novelist. When I say I’m going to write a novel, I immediately see a structure, I see climaxes, I see a dénouement, I see a beginning, I see an end. This is what a novel is. It is a structure. I don’t know how far the writer of a novel is communicating himself, his ideas, his feelings. This is probably what makes the poem rather different from the novel. The poem is a means of communicating emotions to the world whereas the novelist is not communicating himself at all. Although I would say this, when we judge a novel, we tend to judge the quality of the mind of the creator. Do we like the mind of the person who wrote the novel? Do we like the mind of Flaubert, of Balzac? In that sense the novelist is communication a personality, but not ideas, or emotions, or feelings.

Gustave Flaubert, 1869, Nadar | Honoré de Balzac, 1842, Louis-Auguste Bisson

IV. THE GREATNESS OF LIFE LIVED

If I understand what you are saying, the new novel would communicate more than the traditional novel in which the novelist is obliged to step aside in favor of their characters so that their novel will live, while in the new novel, on the other hand, the novelist empties the whole space of the novel.

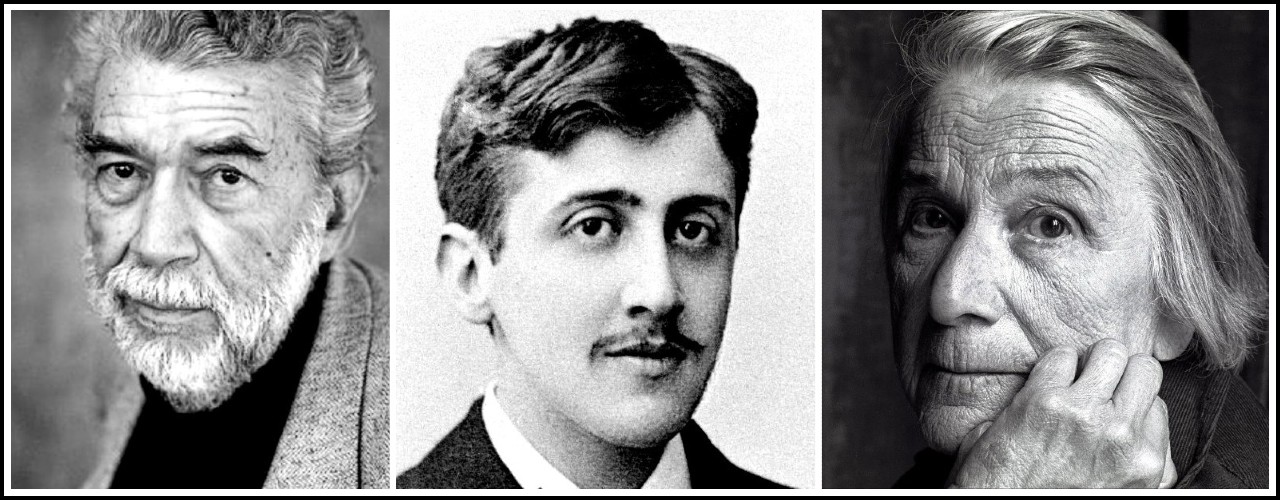

Of course if the nouveau romancier has to obliterate human character from his fiction, he must obliterate his own character. I believe Robbe-Grillet has achieved this; I am not aware of his personality when I read his work. What, however, I am aware of is a certain philosophical theory that he is presenting in his fiction. This is a kind of communication. I think that he and Nathalie Sarraute are communicating a philosophical idea, rather blatantly, because they are not hiding it sufficiently. With Marcel Proust, for example, you have a huge novel, communicating philosophical ideas, about Time, chiefly, but Proust creates his characters so beautifully, creates the physical world so magnificently that the philosophical background remains the background while with nouveaux romanciers it is too much in the foreground. I do not think you can allow that in fiction. In fiction, you’ve got to confront people, eating, making love, walking in the streets, doing things and, of course, this is what Proust gives us. It is the greatness of Proust, it is the greatness of life lived. When I remember Proust, I do not only remember the madeleine dipped in tea but also the smell of the urine of young Marcel when he has eaten asparagus. This is life, the smell, the feel, the taste of life, while in the nouveau romancier you are smelling Husserl all the time and not life.

Alain Robbe-Grillet | Marcel Proust | Nathalie Sarraute

V. THE IMPORTANCE OF INDIVIDUALITY

Then you recommend instead a deepening of the humanity of the characters.

I think the novel is a humane form. In some ways, perhaps, it is an old-fashioned form. I don’t think it’s possible to produce fiction in a community which does not accept the importance of individuality. The job of the novel is to maintain this old humanistic view that the individual is important. The novel is an old-fashioned humanistic form. It has nothing to do with the new philosophies of Machtpolitik or of communism. The novel hangs on to old standards which are being menaced by modern political systems.

Photo: Getty Images for Unsplashed +

VI. THE NOVEL CONTAINS PRACTICALLY EVERYTHING

Looking at your career which is very full and yet splintered in very diverse directions—music, film, literature, journalism—one gets the impression that being a novelist hasn’t been enough for you and you’ve felt it necessary to glean elsewhere, enriching your novels with music, as with the Napoleon Symphony, or adapt them for film in order to give a new dimension. Do you feel imprisoned within the novel, or is being a novelist for you a matter of borrowing all the other forms of expression to enrich the novel?

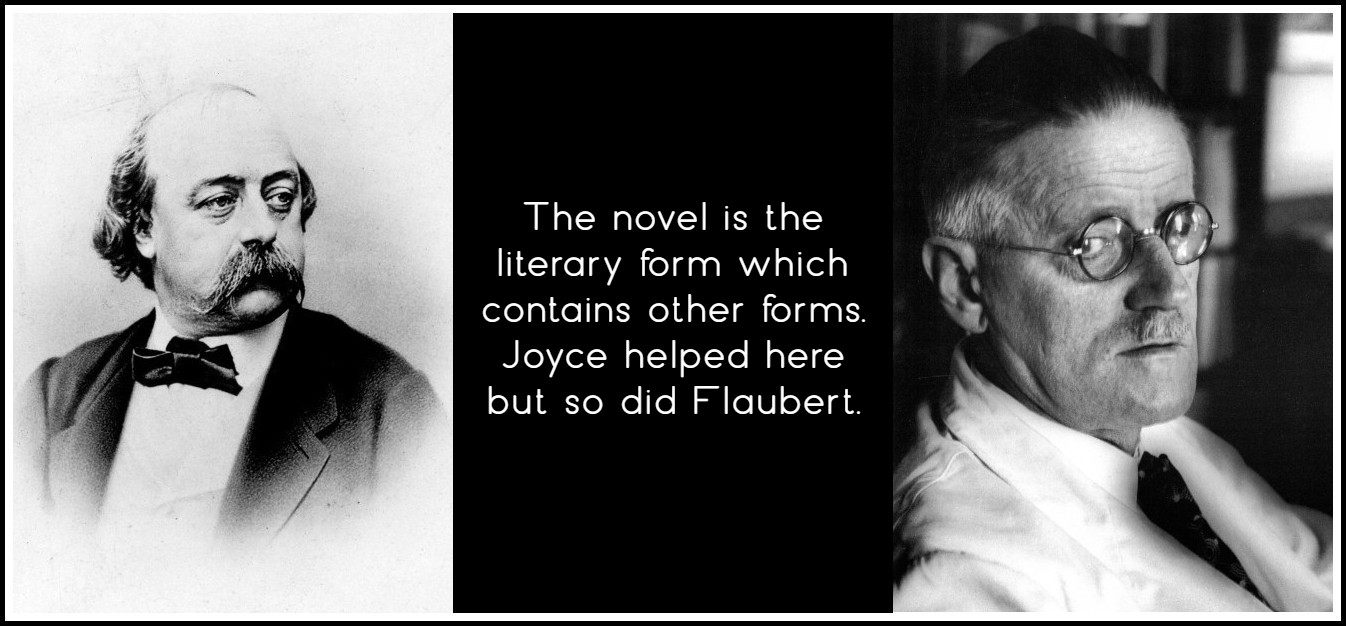

One has to say that practicing other forms such as journalism or the film-scenario is an aspect of the novelist’s life, seen in commercial terms. Very, very few novelists have been able to make a living out of writing fiction. What happens to most of them is they publish one novel, two novels, three novels, and then someone asks them to review novels, and you then find yourself in the world of journalism, without having sought it. I think the same thing is true of film-scripts. To do nothing but write novels is almost impossible nowadays, but the more I practice these other forms, the more I see the novel does contain practically everything. It has emerged as the literary form which contains other forms. Joyce helped here but so did Flaubert.

Gustave Flaubert & James Joyce

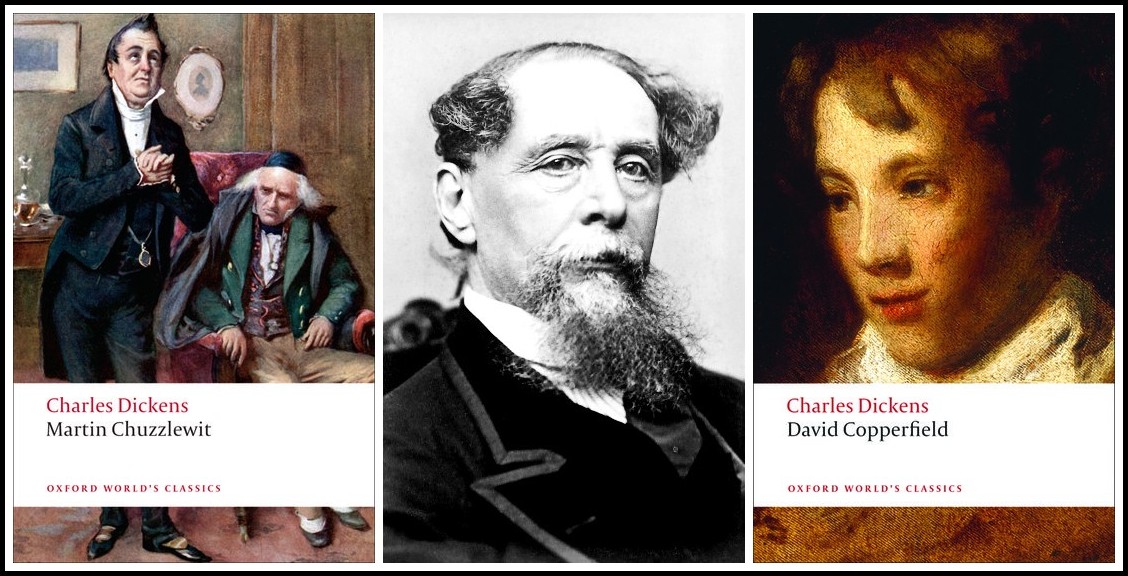

When he wrote the Tentation de Saint Antoine, Flaubert was writing a kind of play, a kind of Freudian fantasy. He was bringing new elements to the novel which Joyce was very quick to pick up on when he wrote Ulysses. They taught us that the novel can contain other forms. The novel is certainly the most satisfactory form we have. It worries me when the French tend to limit the novel. The number of novels that come out in France these days which are very thin, have about 100 pages, 120 pages. This is not what the novel is about. This is not what Balzac or indeed Flaubert or Dickens thought the novel was. The novel to them was a big thing, a big panoramic view of life which contains everything. I hate to bring up this business of commerce again, but in the twentieth century it has not been possible for a novelist to write in the manner of Dickens or Tolstoy because the commercial circumstances have changed. Dickens could write a long novel in installments; he could publish it in fortnightly parts. This was wonderful for him. He’d publish a couple of chapters of David Copperfield, and we would immediately know what the response of his readers was. This was wonderful! He could change the novel as he went along. In Martin Chuzzlewit he sent his characters to America. His readers did not like this so he brought them back again! This was a marvelous rapport between reader and writer.

Martin Chuzzlewit | Charles Dickens by Jeremiah Gurney, 1868 | David Copperfield

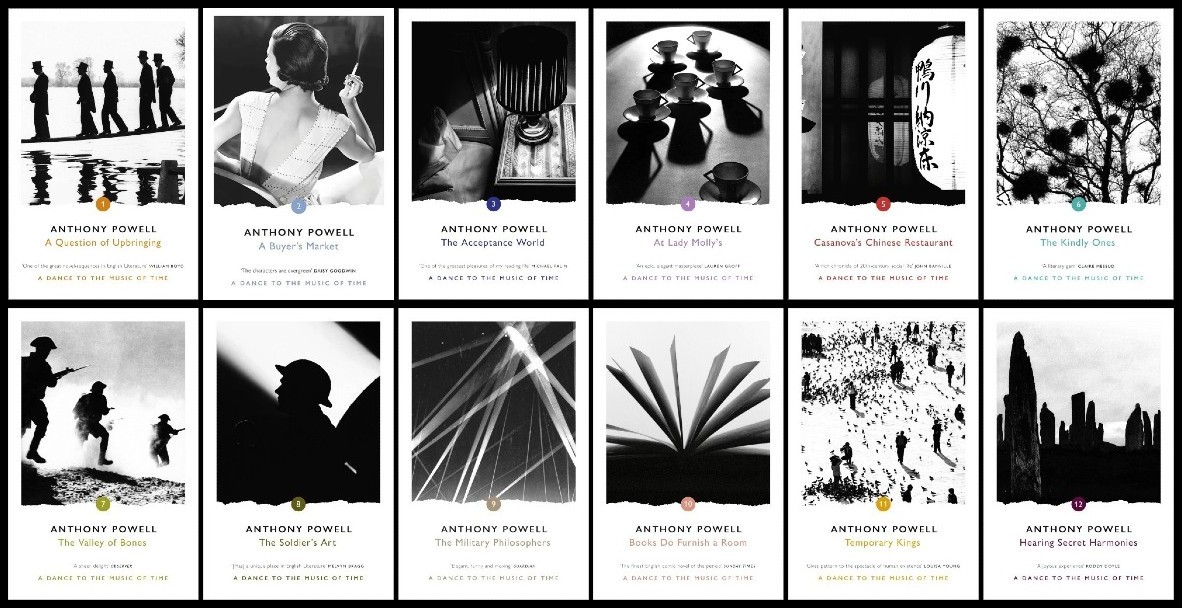

And, of course, this is true also of Tolstoy. War and Peace is a big novel only because it came out in fortnightly parts. We don’t have this any more, unfortunately. I think Joyce was the last writer to have published in this form. We can’t do it any more. Ulysses was published in installments. We can’t do it any more; therefore we cannot produce the big novel in the Dickensian sense, because we are not earning. Dickens was earning as the novel was published. We are not earning any more. We cannot give ourselves years to write a big novel unless we are earning something from some other source so the tendency is to write shorter and shorter novels or to write romans-fleuves in the manner of—in England—Anthony Powell or C. P. Snow. In America, the situation is different because the writers of big novels are usually subsidized by universities. And this is being done by John Barth, Saul Bellow, various others. The big novel has disappeared from Europe chiefly because of financial circumstances. One has to do other things.

Anthony Powell, A Dance to the Music of Time, Volumes 1 – 12

VII. THE SENSE OF AN AUDIENCE

What you say about Dickens and Tolstoy is very interesting because you seem to be implying that the public has its role in the process of producing the form of the novel.

I think it is true. Perhaps Dickens was exceptional in a sense. Dickens of course was primarily a performer. When Dickens became a professional performer, late in life, he disclosed himself as probably one of the greatest actors of all time. A novel is a kind of performance in which you have to have an audience there. What we lack in the twentieth century is this sense of an audience. I find it very strongly in my own work. I publish a novel in England, I read the reviews—of course the reviews don’t mean anything—what do the people think? What do the readers think? What do the people who buy the book think? You don’t know. They very rarely write to you or telephone you. In America they are a little less reserved; they will come forward and discuss things with you. The French will too. But the sense of having an audience there as Tolstoy and Dickens had! This is why the novelist will very frequently, as I do, get on the stage and talk, and recite. I do this in America. In America they will listen to you and I am getting a response. We need this desperately and in Europe we are not getting it.

VIII. AMERICA VS. EUROPE

When you speak of better conditions surrounding the creation of literature in the United States, you refer to the economic aspect. Does the fact that a nation might be strong economically favor the novel that is better distributed, better responded to, whereas in France the writing of literature becomes something more confidentiel [limited to a small circle]?

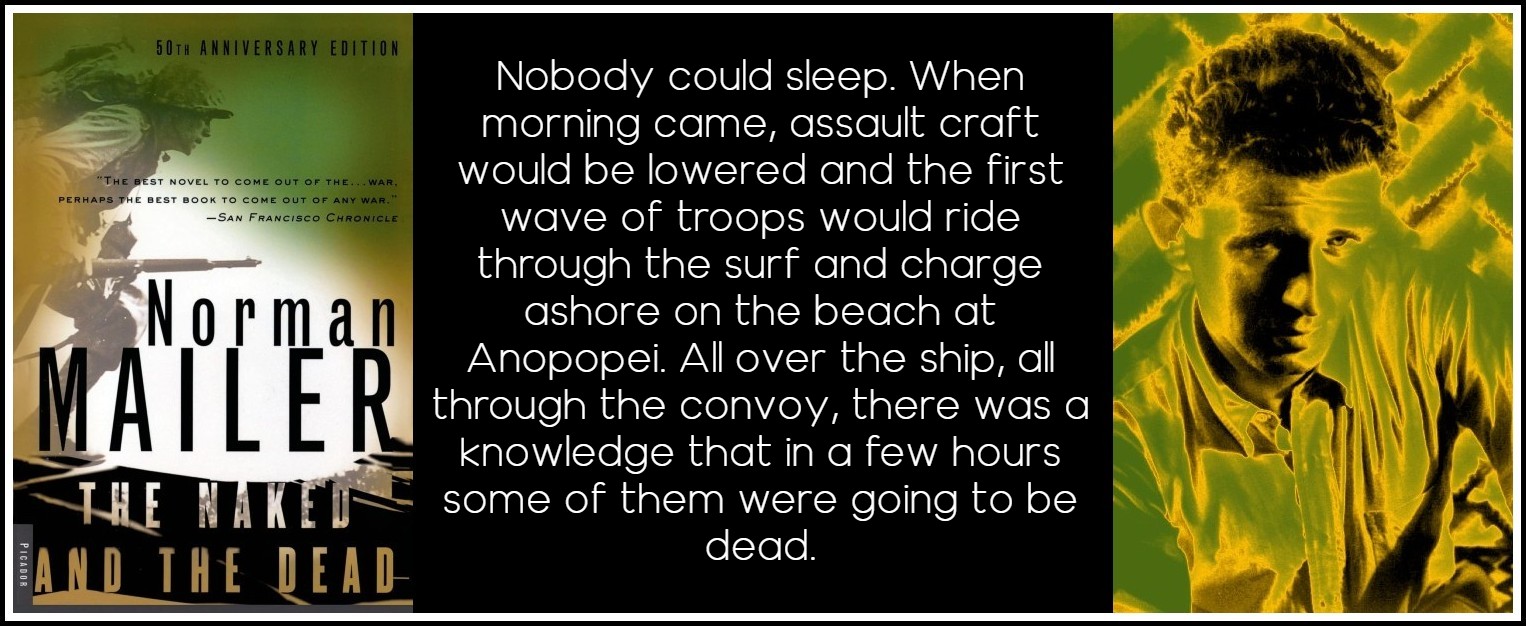

I do feel, increasingly—and France must feel this also—that America is the country where the novel is finding its most typical twentieth-century expression, rightly or wrongly. I mean, the novel is a European creation, but I think America has taken it over, partly because the financial circumstances of the American novelist are so much more favorable than they are in Europe. I don’t think that American novelists are any better than French writers or British writers, but they do have opportunities which we lack. If we think about the progress the novel has made during the twentieth century, the major progress—certainly—of the last thirty years has been made in America. I don’t like this. I’m patriotic enough to want it to have been made in Europe, but, you see, we suffered the war, the second World War, and we produced no great war novel. The Americans did. There was young Norman Mailer, in his twenties, entering the army with the intention of writing a novel about it. And he wrote a big novel, The Naked and the Dead, while we, in Europe, have not produced anything like it. It is not a question of American energy; it is a question of American opportunity.

Norman Mailer, The Naked and the Dead, 1948 | Norman Mailer in 1948 (age 25). Photo (colorized): Carl van Vecht

The novel itself in America can become the raw material of other forms, the television serial, the TV series, the big paperback sales. These commercial factors make novelists of America potentially very powerful people, and very rich. I don’t think this is good for the Americans. We hear too many stories of American authors achieving success and then committing suicide or dying of drink or despair. There is something perhaps wrong with this cult of fame and wealth in America, but on the other hand it has produced for us an image of America as the country where the novel is still a big, living, energetic, panoramic form. It is not so in Europe. We produce these exquisite little things, little novels. American novelists have this sense that writing a novel is big business, that it is not just something you do quietly in your spare time, as the French writer will, as the French homme de lettres does it. Big Business. And it was big business for Dickens, it was big business for Thackeray, it was big business for Balzac. And, probably, the novel has something to do with big business.

Andy Warhol, Dollar Sign, 1981 | Toa Heftiba, Bookshelf, Unsplash

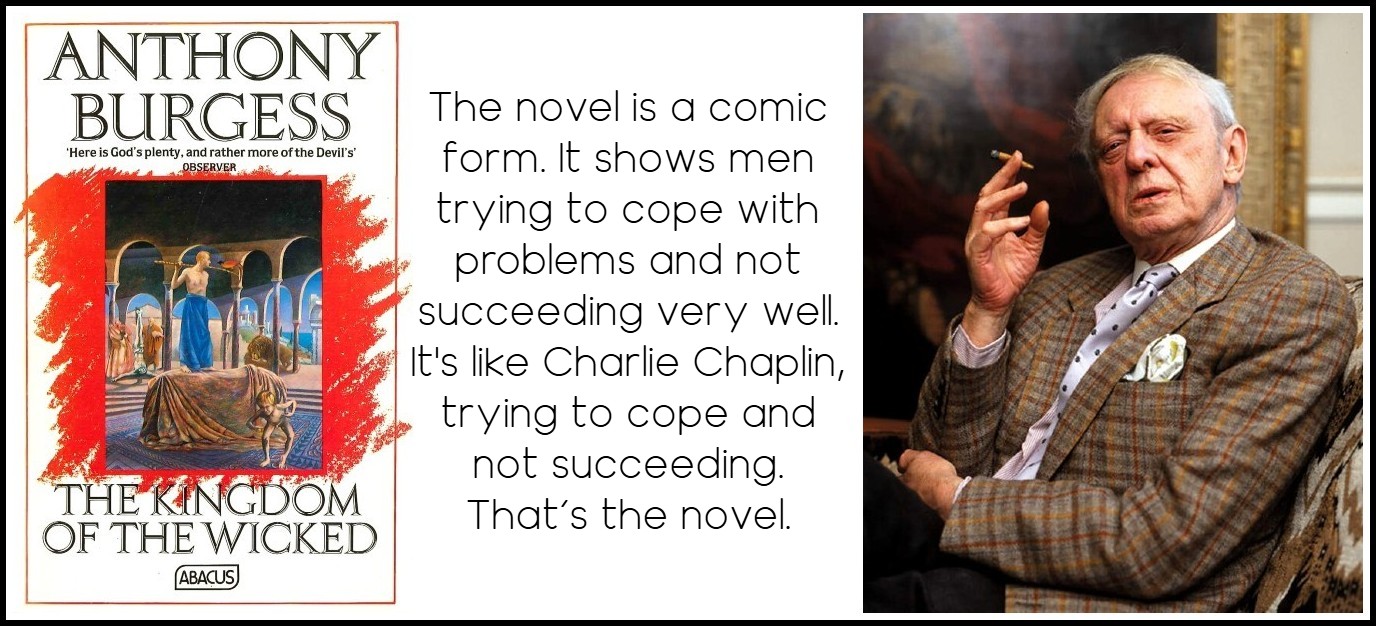

IX. THE NOVEL IS A COMIC FORM

The big sellers of French publishing today are historical novels and even histories. Think of the success of a man such as Le Roy Ladurie or other historians. One has the impression that historical literature, whether it is romanticized or raw, has conquered the field conceded to it by the ‘literature of the laboratory’ which abandoned that human nature you spoke of earlier.

I think this is true. The primary task of the novel may well be to explain what history is about. When Balzac undertook the Comédie humaine his aim was not merely to entertain, only partly that, but to show what a particular phase of history was like. An interpretation of history—possibly this is what the novel is about. What I am trying to do at the moment is write a novel which deals with the first century after the death of Christ. This will be a surprise, and it will shock a lot of people. It is a comic novel. It will make them laugh. If one reads the acts of the apostles—St. Luke, St. Paul, solemn characters; and the persecutions of the Christians are terrible. But look at it from another angle, you find it’s rather comic. It’s a comic study of human beings trying to adapt themselves to a change. Everyone is aware that an ending is coming, the Roman Empire is finishing. I was writing a passage in Switzerland, before I came back here, last November, and this made me laugh. Peter is in the town of Jaffa with a tanner called Simon, and tanning is a dirty business, it smells, they use camel dung. So he gets on the roof to get away from the smell. Because he is on the roof, they forget he is there and don’t give him any dinner. So he is hungry. So he dreams of food. He dreams of everything, of pork, goatmilk, and a voice says: ‘Eat, all is good.’ And he wakes up and he’s had a vision from heaven and the whole of Jewish dietary taboos have been broken. This is a comic circumstance. When we read the Scriptures we are told to look at it solemnly. The novelist can make it more human; he can show it in comic terms. The novel is a comic form; it shows men trying to cope with problems and not succeeding very well. It is like Charlie Chaplin, trying to cope and not succeeding. That’s the novel.

Anthony Burgess, The Kingdom of the Wicked, 1985

That endeavor to rewrite history which is the honor of the great novelist, from your point of view, and that interaction between the comic and the tragic, you have just attempted to accomplish in Earthly Powers.

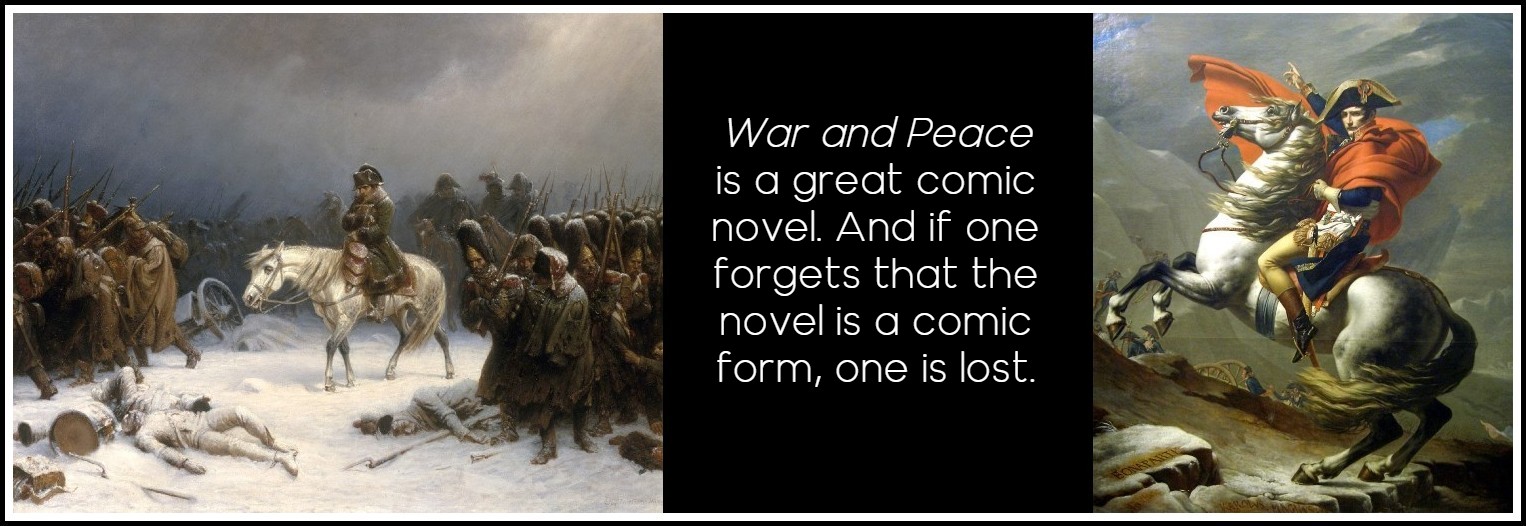

I tried that, yes, but this is old as the novel itself. If we go back to what I always regard as the first three novels, the Satyricon, and the novels of Longus and Apuleus, they are comic. Satyricon is a comic novel. It is historical. The Neronic period. Homosexuals trying to cope with a heterosexual morality. The novel does not end, unfortunately. When we come to Don Quixote that is definitely comic—a man trying to cope with mad ideas, trying to cope with a sane world, or perhaps he is sane and it’s the world that is mad. I think that even War and Peace is a great comic novel. Napoleon is to some extent reduced to a comic figure trying to cope with destiny, with forces of history which he does not quite understand. And if one forgets that the novel is a comic form and is made to make you laugh, one is lost. I was very upset about my friend and colleague William Golding who got the Nobel Prize recently, because if any man has gone against the spirit of the novel, it’s Golding. The novel with him has become a kind of grim theological tract in which man is evil. You don’t laugh at Golding’s books. There is nothing funny in them. And I think the novel is a funny form. Balzac is funny, Flaubert is funny, even Zola is funny… comme la vie elle-même [like life itself].

Adolph Northen, Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow, 1851 | Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 1801

X. THE NOVEL IS HERE TO STAY

Then you think that the novel is eternal, that it ought to embrace life, even if it transforms life into its own image, but that eventually creative writers, whatever their historical era, have a common language, understood across the centuries?

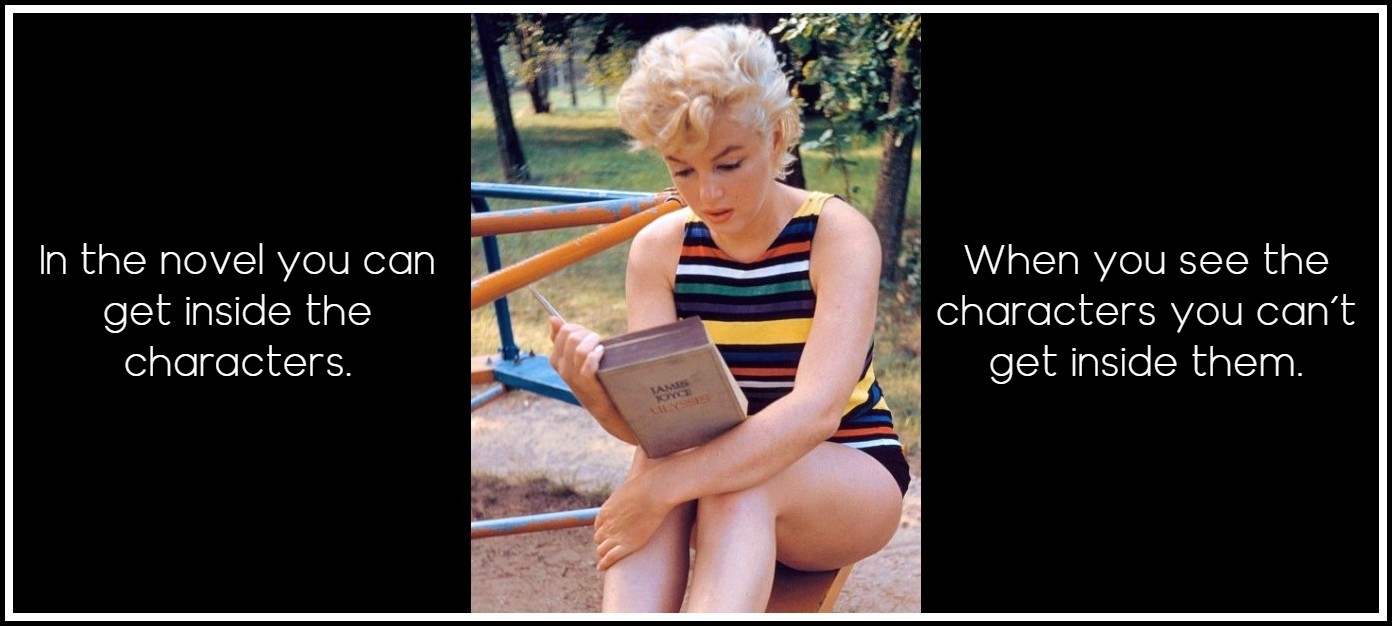

Yes, I think that’s true. The novel is not like poetry. The novel can transcend languages. The essence is always there. The same characters. The novel travels through history. The greatest invention of all time is still the book. You can put in your pocket a paperback of War and Peace and take it out and read it whenever you will. I don’t think we are going to throw this over in a great hurry. As people are learning, when they see film versions of great novels, there is more in the novel. In the novel you can get inside the characters, when you see the characters you can’t get inside them. The novel is here to stay, I’m quite sure of that.*

* I have deleted from this paragraph Burgess’s references to an archaic technology, the video cassette, while respecting, of course, the integrity of his argument. (R.J.)

Marilyn Monroe reading James Joyce’s Ulysses, Long Island, 1955 | Photo: Eve Arnold

Eve Arnold: ‘She said she kept Ulysses in her car and had been reading it for a long time. She said she loved the sound of it and would read it aloud to herself to try to make sense of it — but she found it hard going.’ Source: Open Culture.

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments