Georges Bataille

FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN MADAME EDWARDA AND STORY OF THE EYE

Cathy MacGregor

From Cathy MacGregor, ‘The Eye of the Storm: Female Representation in Bataille’s Madame Edwarda and Histoire de l’oeil’ in Andrew Hussey, editor, The Beast at Heaven’s Gate: Georges Bataille and the Art of Transgression (Amsterdam & New York: Rodolphi, 2006) pp. 101 -110

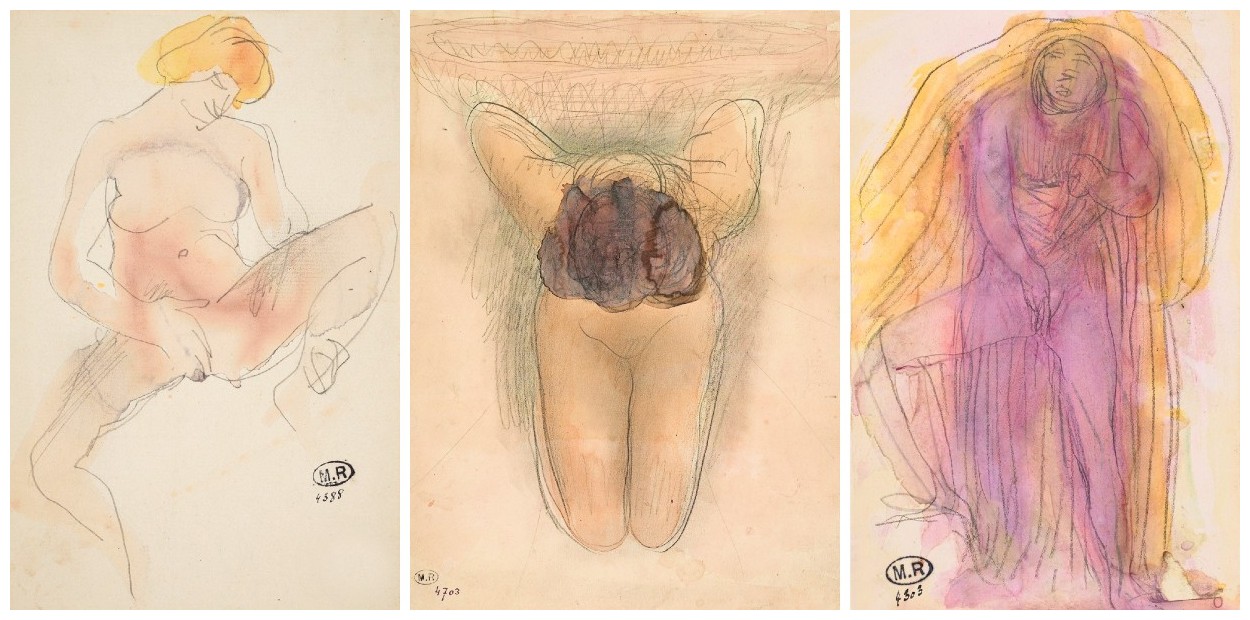

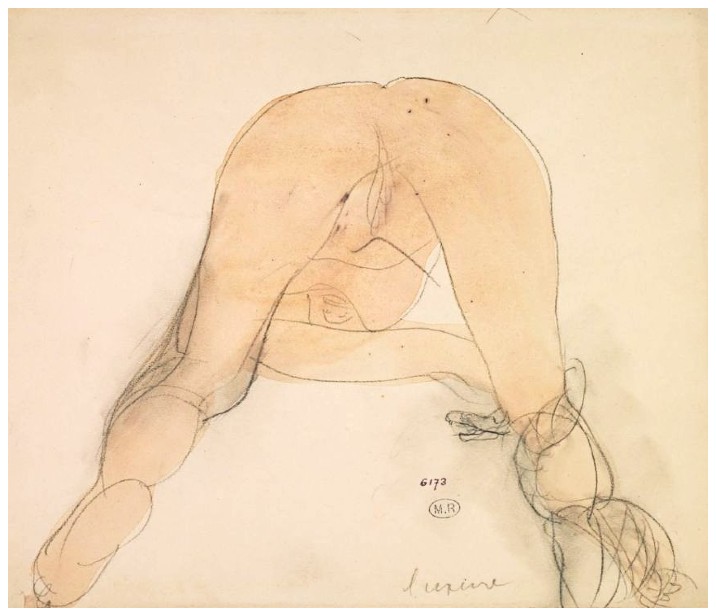

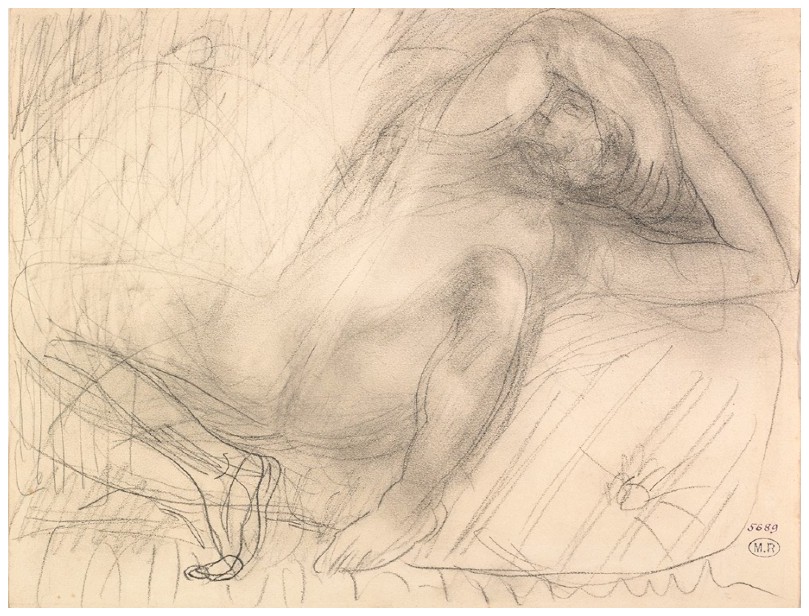

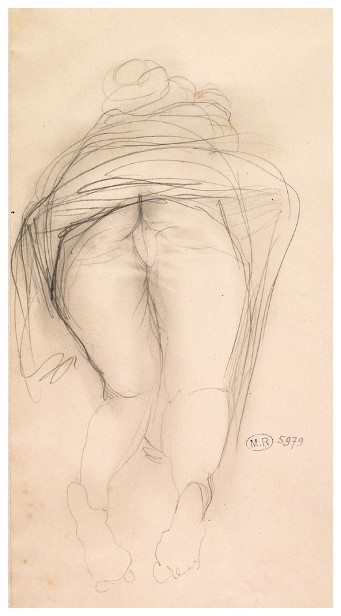

Rodin, Femme nue, jambe gauche écartée, 1895

I. INTRODUCTION

The figure of woman is key in Bataille’s literature and its desire to question the formulation of society and the constraints which it places upon the free will of the individual. The women in Bataille’s fiction frequently serve as the catalyst to an orgy of abasement and abjection which denudes the self of its trappings of social restraint. The Dionysian potential for animality in all of us exerts a powerful force in Bataille’s work and, like Nietzsche’s reading of Greek tragedy, this potential can only co-exist with that which it is reacting against and in fact gains its momentum from this co-existence. The abyss of the tension between being oneself/being other and the interlinking of the two is the basis for many of Bataille’s novels. As in post structuralism, woman acts as an important metaphor; the female body in general and the genitals in particular provide an important organizing metaphor in the novels. This metaphorical use of the female body echoes the use of the feminine in other modernist texts where the quest for new forms with which to explore being are fixed onto the irrational and the unconscious as forces to critique existing frameworks of knowledge. This exploration is conflated with a use of the ‘feminine’ as metaphor, as Alice Jardine observes: We might say that what is generally referred to as modernity is precisely the acutely interior, unabashedly incestuous exploration of these new female spaces: the perhaps historically unprecedented exploration of the female, differently maternal body. In France this exploration has settled on the concept of ‘woman’ or the feminine as both a metaphor of reading and topography of writing for confronting the breakdown of the paternal metaphor.’1

1 – Alice Jardine, Gynesis (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1995) p.34

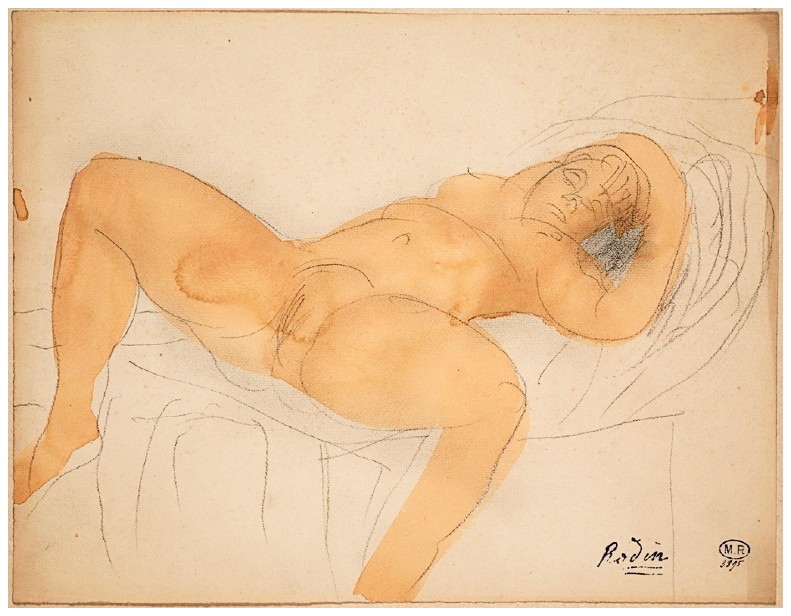

Rodin, Femme nue debout, se pressant les seins, 1900

Although much of Jardine’s argument refers to theoretical writing, in turn many of these theorists had been influenced by Bataille’s work or had recognised a common sensibility in his pre-figuration of shared themes. It is true to say that Bataille’s writing is acutely interior, rooted in the existential crises of its protagonists, crises which are frequently provoked by or related to the performative display of female sexuality. In this paper I will argue that performance and its relationship with ritual can provide a useful topography for a reading of Bataille’s erotic fictions.

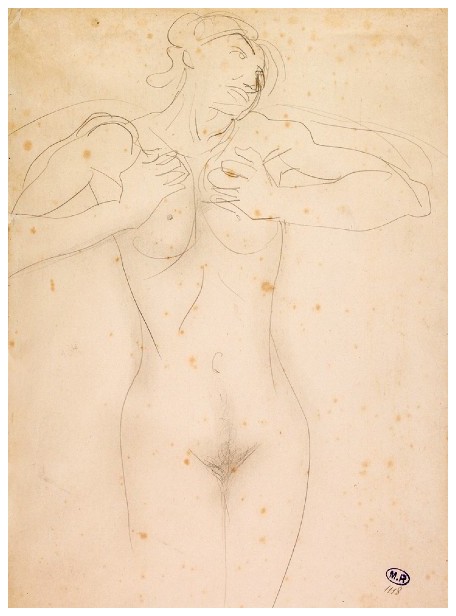

RODIN: Amour et Psyché sortant d’un lotus | Deux femmes enlacées, 1908

Transgression in Bataille becomes an individual ritual by which the subject exceeds the boundaries of everyday life, be they sexual, economic or religious. This transgressive action becomes a conscious performance of the violation of social norms, as when the priest, Don Aminado, is murdered in Histoire de l’oeil. The description of this episode in the novel is a strange mixture of uncontrollable frenzy and organised ritual inversion in which ritual objects come to stand for other objects and to provoke a series of metaphoric associations:

Sir Edmond qui avait cette fois barricadé la porte et fouillant dans les armoires finit enfin par trouver un grand calice et nous demanda d’abandonner un instant le misérable.

— Tu vois, expliquait-il à Simone, les hosties qui sont dans le ciboire et ici le calice dans lequel on met du vin blanc.

— Ça sent le foutre, dit Simone, en reniflant les pains azymes.

— Justement, continua Sir Edmond, les hosties, comme tu voies, ne sont autres que le sperme du Christ sous forme du petit gâteau blanc. Et quant au vin qu’on met dans le calice les ecclésiatiques disent que c’est le sang du Christ, mais il est évident qu’ils se trompent. S’ils pensaient vraiment que c’est le sang, ils emploieraient du vin rouge, mais comme ils se servent uniquement de vin blanc, ils montrent ainsi qu’au fond du cœur, ils savent bien que c’est l’urine.

La lucidité de cette démonstration était si convaincante que Simone et moi, sans besoin de plus d’explication, elle armée du calice, moi du ciboire, nous dirigeâmes vers Don Aminado qui était resté comme inerte dans son fauteuil, à peine agité par un léger tremblement de tout le corps.

— Ça n’est pas tout ça, fit-elle sur un ton qui n’admettait aucune réplique, il faut pisser.

Et elle frappa une seconde fois au visage avec le calice: mais en même temps elle se dénudait devant lui et je la branlais.1

1 – Histoire de l’œil (Paris: Gallimard, 1973) p. 56

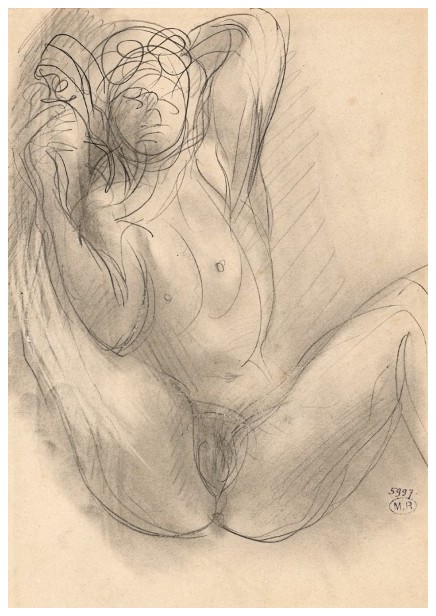

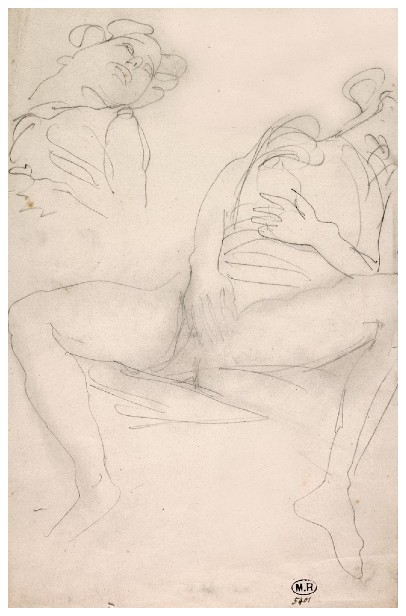

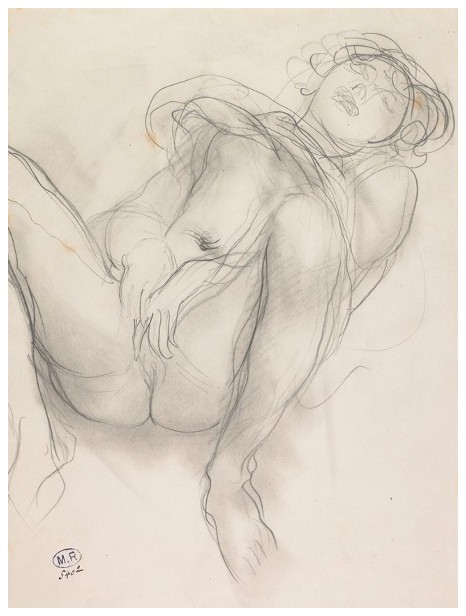

RODIN: Femme nue assise, jambes écartées, main au sexe | Femme nue agenouillée, penchée en avant, mains derrière le dos | Femme nue debout, la main droite au sexe

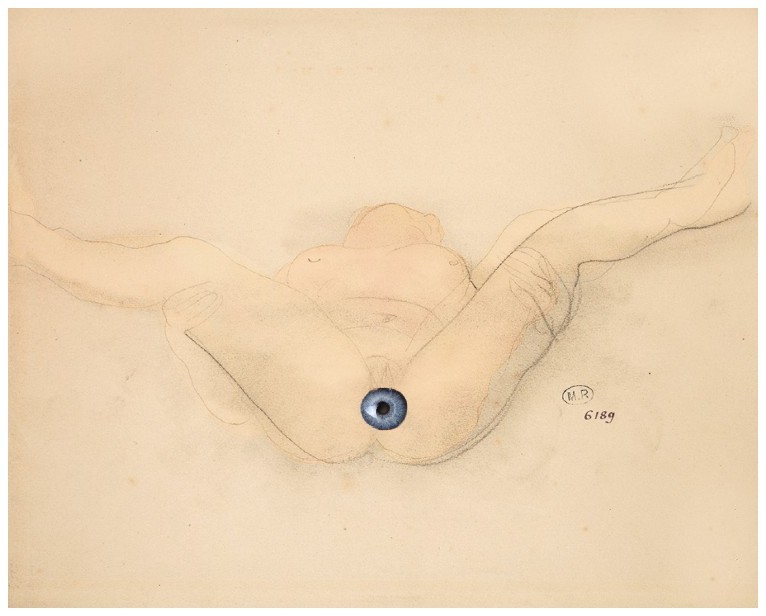

The inversion of the mass is enacted through and upon the human body, particularly the lower body, or what Bakhtin identified as the ‘grotesque body’. As in Bakhtin’s formulation of carnival, Bataille emphasises the ambivalent nature of the human body and its role in stripping away the artifice of social codes. The ripping out of Don Aminado’s eye provides the climax of the metaphorical slippage between eyes and eggs in the text. But the action of Don Aminado’s eye being ripped out, potentially a reference to the key tragic moment of western culture, is then surpassed by a greater moment of horror which is literally experienced through a female body: Ensuite je me levai et en écartant les cuisses de Simone, qui s’était couchée sur le côte, je me trouvai en face de ce que, je me le figure ainsi, j’attendais depuis toujours de la même façon qu’une guillotine attend un cou à trancher. Il me semblait même que mes yeux me sortaient de la tête comme s’ils étaient érectiles à force d’horreur; je vis exactement, dans le vagin velu de Simone, l’œil bleu pâle de Marcelle qui me regardait en pleurant des larmes d’urine. Des trainées de foutre dans le poil fumant achevaient de donner à cette vision lunaire un caractère de tristesse désastreuse.1 Bodily order and organisation becomes completely confused and disorganized, literally representing the de-territorialization of the subject. But the notion of witnessing this transgression within the female body is key. The naked female body is transformed from a passive object to an active site of transgressive horror. Like shamans, women in Bataille’s fiction go beyond the boundaries of social experience and then come back to bear witness.

1 – Oeuvres complètes, I; p. 69

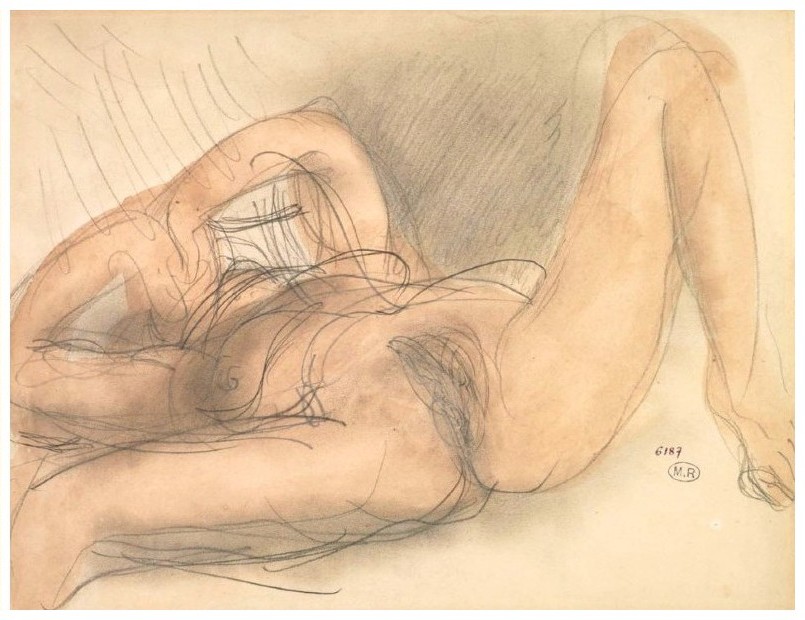

RODIN: Coquille (D5990) | Femme nue sur le dos et de face, bras et jambes repliés et écartés (D6187)

II. THE EYE OF THE STORM

What may provide the more revolutionary aspect in a reading of Bataille’s erotic fiction is not the transgressive trajectory of his male narrators but the explosive transgressive potential of the female characters. Bataille’s use of female characters can be understood in relation to both Julia Kristeva’s use of the abject and Gilles Deleuze’s and Felix Guattari’s notion of ‘becoming-woman’. Kristeva defines the abject firstly by its otherness, but not otherness in the usual sense of being an object, an other, rather: the abject has only one quality of the object—that of being opposed to I.1 Whereas subject/object relations imply a framework of recognizable meaning, the abject threatens this very framework: What is abject, on the contrary, the jettisoned object, is radically excluded and draws me towards the place where meaning collapses.2 The place where meaning collapses is, in Kristeva’s analysis, associated most strongly with the feminine in general and the mother in particular: The abject confronts us on the other hand, and this time, within our own personal archaeology, with our earliest attempts to release hold of this maternal entity even before existing outside of her, thanks to the autonomy of language. It is a violent, clumsy, breaking away with the constant risk of falling back under the sway of a power as securing as it is stifling.3

1 – Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982) p. 1

2 – Powers of Horror, p. 2

3 – Powers of Horror, p. 13

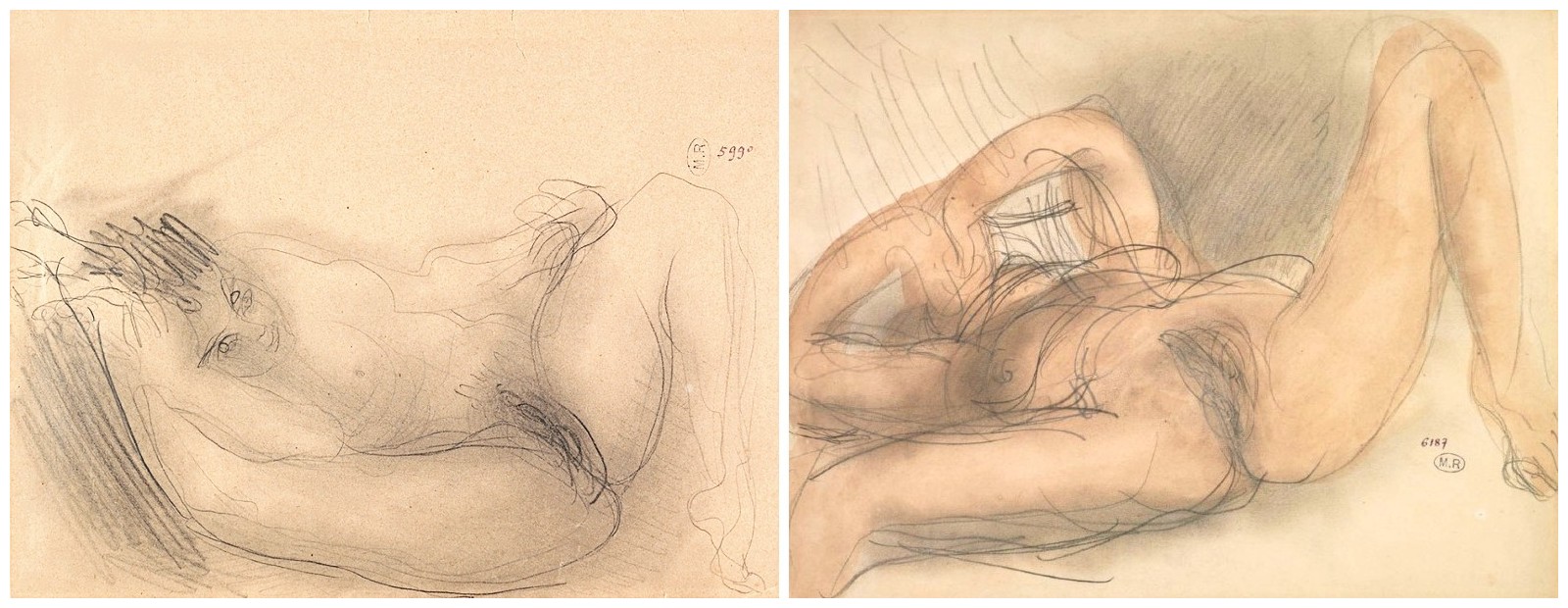

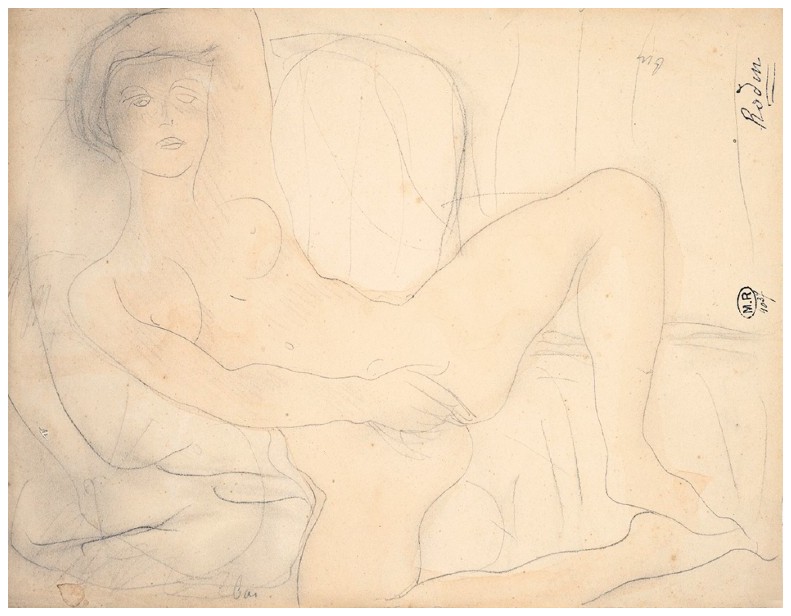

Rodin, Avant la création

Bataille uses female sexuality in his erotic fiction to highlight the inadequacies of the meanings with which society invests gender, sexuality and the family. Yet, like the use of ritualistic inversion, this valorization of the feminine is ambivalent in its tone, for in Bataille, the female body is also primarily a site of abjection where all meanings, particularly those made by masculine subjectivity, are under attack. Yet this does not imply that women are supremely disadvantaged in Bataille’s fiction in relation to men, in fact I would suggest that the reverse is actually true. The female body is used by Bataille to represent the centre of a deconstructive impulse in his fiction which produces seismic ripples resulting in a profound shift in the reality relayed to the reader by the male protagonists. The female body in general, and the vagina in particular, become the eye of this deconstructive storm. The way in which Bataille represents the vagina can be seen implicitly to refer to some of the epistemological shifts in subjectivity elucidated by feminist philosophers such as Luce Irigaray. Irigaray writes of female sexuality and sex organs as an impossible referent within the symbolic order: Her sexual organ represents the horror of nothing to see. A defect in the systematics of representation and desire. A ‘hole’ in the scopophilic lens.1 This is not to say that Bataille does not represent the penis at all; in fact it could be said that there are penises all over the place. However, at the centre of the two main texts I have focused on is the representation of the vagina; not as object but rather as abject. The cunt literally becomes the place where meaning is made redundant and into which the male subject disappears.

1 – Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which is Not One (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1985) p. 26

Rodin, Sexe de femme

The way in which the female body is used as an abject in Bataille’s fiction also, to some extent, connects to Derrida’s identification of the feminine in representation as a hinge, a term that operates both within and without the representational system. Although Bataille does this linguistically, I am more interested in how he achieves this imagistically and metaphorically by placing the female body, the impossible referent, at the centre of representation in order to see what happens to the rest of the discourse. The cunt becomes a device which shatters phallocentric meaning in the text:

La voix de Mme Edwarda, comme son corps gracile, était obscène:

– Tu veux voir mes guenilles? disait-elle. Les deux mains agrippées à la table, je me tournai vers elle. Ainsi, elle maintenait haute un jambe écartée: pour mieux ouvrir la fente, elle achevait de tirer le peau des deux mains. Ainsi les ‘guenilles’ d’Edwarda me regardaient, velues et voces, pleines de vie comme une pieuvre répugnante. Je balbutiai doucement:

– Pourquoi fais-tu cela?

– Tu vois, dit-elle, je suis DIEU.1

1 – Oeuvres complètes, III, pp. 20-21

Rodin, Femme nue sur le dos, les mains au sexe et les jambes soulevées

Edwarda’s action effects a shift in the récit and shifts creating a landscape where anything can happen and anything can make sense. The universe which the ‘characters’ inhabit is described variously as ‘mad and void’, ‘a lifeless hollow solitude’, ‘an absence, far out of range and beyond the possibility of any laughter’. Even when the narrator takes up the position of direct authorial address to the reader, the usual position of supreme knowledge and making of meaning, he cannot offer any kind of adequate logical explanation: Je m’explique: il est vain de faire une part à l’ironie quand je dis de Mme Edwarda qu’elle est DIEU. Mais que DIEU soit une prostituée de maison close et une folle, ceci n’a pas de sens en raison.1

1 – Œuvres complètes, III, p. 30

Rodin, Luxure

Although he refuses the optic of philosophy, at the end of the novel the narrator lapses into an enquiry upon meaning and absence: Ma vie n’a de sens qu’a la condition que j’en manque; que je sois fou: comprenne qui peut, comprenne qui meurt; ainsi l’être est là, ne sachant pourquoi, de fond demeuré tremblant; (‘immensité’, la nuit l’environnent et, tout exprès, il est là pour ‘ne pas savoir’. Mais DIEU? qu’en dire, messieurs Disert, messieurs Croyant? Dieu, du moins, saurait-il? DIEU, s’il ‘savait’, serait un porc. Seigneur, (j’en appelle, dans ma détresse, à ‘mon cœur’) déliverez-moi, aveuglez-les! Le récit, le continuerai-je ?).1 Edwarda’s initial aggressive yet bored performative display has provoked a crisis in the narrator which can only end in death, either that of the subject or the author or both. The end of the novel suggests a reverse catharsis, not into the self-knowledge of the classic tragic protagonist but into absence and lack of fixed meaning. The narrator’s desire to ‘let me be mad’, suggests a reversal of King Lear’s ‘Oh let me not be mad’ and, unlike Oedipus, he is the one who can see whereas the communitas is blinded.

1 – Oeuvres complètes, III, p. 31

Rodin, Femme nue, cuisses hautes et écartées

In the initial display of her cunt Edwarda is giving the narrator permission to see, but what he sees is too much because it not enough. By situating her as GOD Bataille places Edwarda not as merely an object but, I would suggest, as an abject. The absurdity inherent in her declaration suggests what Kristeva terms ‘the confrontation with the feminine’ in its aspect of undoing identity: What we designate as ‘feminine’, far from being a primeval essence, will be seen as an ‘other’ without a name, which subjective experience confronts when it does not stop at the appearance of its identity.1 Bataille’s construction of the female body as a site of abjection which undoes masculine logic is played out again and again throughout the texts. When Edwarda displays her cunt the confusion of the narrator expressed through the question: Why are you doing that? is answered by an alternative logic which manages to be both absurd, blasphemous and, in its own terms, entirely rational: You can see for yourself. I’m GOD. The protagonist is plunged into a world of desolation and abjection where the notion of God as a public whore or of a public whore as God makes perfect sense.

1 – Powers of Horror, pp. 58-59

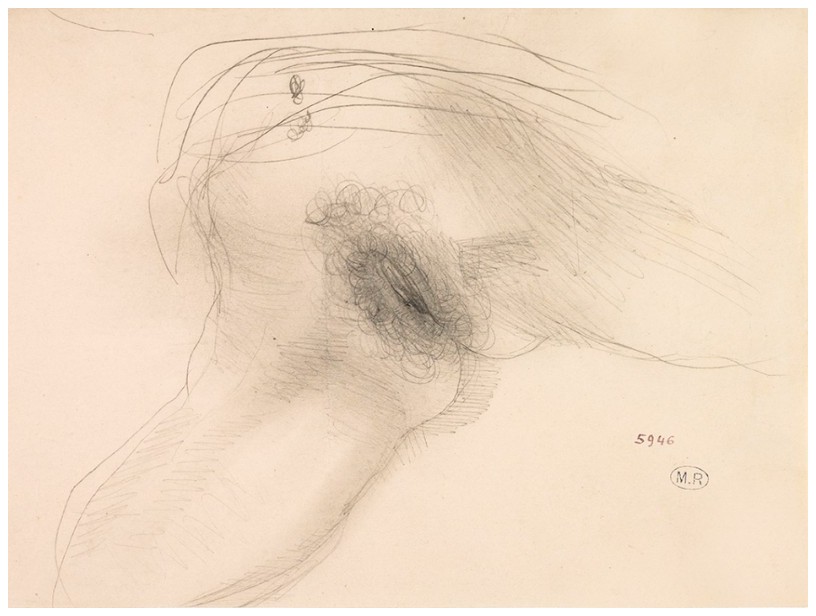

Femme nue sur le dos et de face, bras et jambes repliés et écartés

In these novels the female body becomes a conduit for the enactment of masculine transgression, as Judith Surkis observes: For Bataille, the woman as the marker of difference, becomes the site upon which transgression appears. This is where the gendered erotic object comes into play. Bataille’s eroticism posits a distance and difference between partners in order to permit the presentation of an image or ‘evidence’ of transgression.1 In both Histoire de l’oeil and Madame Edwarda, women become the performers in a theatre of masculine erotic transgression. Does this suggest merely a parallel with hard-core pornography: a spectacle organised for and by men; and is the distinction between woman as object and abject merely semantic, as in both cases she is always something else? Carolyn Dean asks if women can play a part in Bataille’s model of transgression given their ontological lack; in other words, how can a woman really transgress if she does not have a subjective position to transgress from? In Histoire de l’oeil, the two female figures, Simone and Marcelle, are represented as mirror images and are therefore potentially interchangeable. The best example of this appears in the first attempt to rescue Marcelle from the asylum: Simone laissa tomber ensuite la main le long du ventre jusqu’à la fourrure. Marcelle l’imita alors et en même temps posant un pied sur le rebord de la fenêtre découvert une jambe que des bas de soie blanche gainaient presque jusqu’à son cul blond. Chose curieuse, elle avait une ceinture blanche et des bas blancs alors que la noire Simone, dont le cul chargeait ma main, avait une ceinture noire et des bas noirs.1 The feminine as a radically undifferentiated Other represents for Bataille’s transgressive male protagonists their end goal of, literally, losing themselves.

1 – Judith Surkis, ‘No fun until somebody loses an eye: Masculinity in The Story of the Eye’, Diacritics, 1996, p. 21

2 – Œuvres complètes, I, p. 31

Rodin, Femme allongée, main sur sexe, jambes écartées

The dissolution of the old dialectics of binary representation may represent a radical position in sexual representation—to deny any possibility of otherness through lack of definition. This idea is outlined by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus as a means of resisting selfhood as constructed by modern society: You will be organised, you will be an organism, you will articulate your body, otherwise you’re just depraved. You will be signifier and signified, interpreter and interpreted—otherwise you’re just a tramp. To the strata as a whole the Body without Organs opposes disarticulation (or n articulations) as the property of the plane of consistency, experimentation as the operation on that plane (no signifier, never interpret!) and nomadism as the movement (keep moving, even in place, never stop moving, motionless voyage, desubjectification.1 The moments of witnessing the other for the male protagonists are also moments of opening up to the possibility of becoming other. Again the notion of the feminine as performative comes into play; the actor as performer, wearer of masks, resists a basic level of definition. But the problem for reading women in Bataille is that their performance needs a male audience which then takes over by making the transgressive experience his own existential crisis.

1 – Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, A Thousand Plateaus (London: Athlone Press, 1988) p. 159

Rodin, Femme nue allongée aux jambes écartées

III. NOTHING TO SEE

Seeing is of tantamount importance in Bataille’s novels, but looking too much carries the risk that there will be nothing more to see. Witnessing transgression enacted by a woman is the catalyst for an experiential shift in the male protagonist’s view of reality. Yet in tandem with this is the fact that, for these men, the end result of transgression is impotence in both senses of the word. As Simone fucks the dead priest in Histoire de l’œil, the narrator finds himself unable to do anything: Simone restait étendue sur le plancher, le ventre en I’ air, la cuisse encore souillée par le sperme du mort qui avait coulé hors dela vulve. Je m’allongeai auprès d’elle pour la violer et la foutre à mon tour, mais je ne pouvais que le serrer dans mes bras et lui baiser le bouche à cause d’une étrange paralysie intérieure profondément causée par mon amour pour la jeune fille et la mort de l’innommable. Je n’ai jamais été aussi content.1

1 – Œuvres complètes, p. 67

Rodin, Femme nue allongée aux jambes écartées

The dissolution of self represented by the priest’s murder and Simone’s sexual climax negate the narrator’s desire to ‘be a man’ in the most basic sense; to have an erection and metaphorically to erect meaning through the power of male subjectivity. In the same way, the narrator of Madame Edwarda is stultified after watching Edwarda fuck the taxi driver: Mon angoisse s’opposait au plaisir que j’aurais dû vouloir: le plaisir douloureux d’Edwarda me donna un sentiment épuisant de miracle. Ma détresse et ma fièvre me semblaient peu, mais c’étais là ce que j’avais les seules grandeurs en moi qui répondissent à l’extase de celle que, dans le fond d’un froid silence, j’appelais ‘mon cœur’. In the face of female orgasm both men are rendered helpless; this is partly because there is nothing to see, no definable way of knowing the ‘truth’. The narrator in Madame Edwarda cannot know that Edwarda has come, he can only suggest that: I sensed her joy’s torrent run free. But Bataille does attempt to give a visual cue by displacing signs of male ejaculation up to Edwarda’s eye: Je lui vis les yeux blancs. Ses yeux se rétablirent, un instant même elle parut s’apaiser. Elle me vit: de son regard, à ce moment-là, je sus qu’il revenait de l’impossible et je vis, au fond d’elle, une fixité vertigineuse. A la racine, la crue qui l’inonda rejaillit dans ses larmes: les larmes ruisselèrent des yeux.2

1 – Georges Bataille, Madame Edwarda (Paris: Gallimard, 1956) p. 52

2 – Madame Edwarda, p. 51

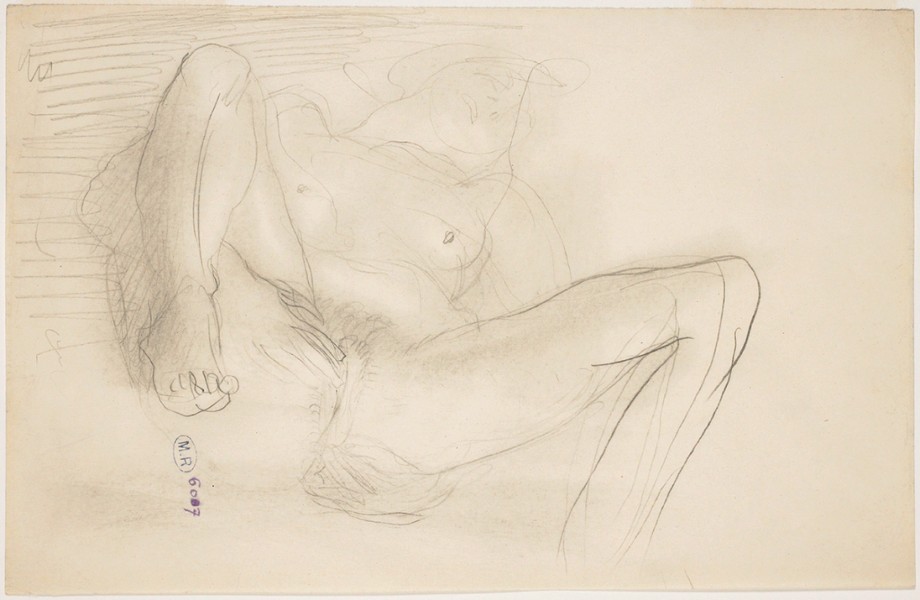

Rodin, Femme nue allongée, jambes écartées, mains au sexe

The link between seeing and transgression has been discussed in many other articles in relation to Bataille’s work, but, in relation to the liminal position of women in his fiction, I feel that the notion of ‘nothing to see’ is of prime importance. Women are located culturally as seen rather than seeing and Bataille seems to fall into the trap of many male avant-garde writers who trope femininity in their writing. Ultimately, being the other can only be a choice if you are not the other, i.e. if you have the power to choose. But, to conclude, I would like to suggest a way of reading Bataille’s women more positively in relation to Benjamin’s notion of the dialectical image and the concept of masquerade or performance. Writing in relation to performance art, American critic Rebecca Schneider defines dialectical images as those that: show the show, which make it apparent that they are not entirely that which they have been given to represent—the way cracks in face paint or runs in mascara might show the material in tension with the constructed ideal.1

1 – Rebecca Schneider, The Explicit Body in Performance (London: Routledge, 1997) p. 52

Rodin, Femme nue étendue, une main au sexe

Benjamin cited prostitutes as one of the best examples of a dialectical image due to their position as both commodity and seller. The dialectical image marks a rupture in the myths of cohesion upon which society tries to found itself. This is where Bataille’s representation of women (and men) could be situated as essentially a performance of gendered and sexual transgression which attempts to ‘show the joins’ in what society has constructed as acceptable sexual expression for men and for women. Performance can provide a useful methodology to explain what Bataille is trying to do. Performance can be defined as a liminal state, a sense of both being oneself and being other. This liminality has always made performer marginal in society. Performance is grounded in slippage between subjectivity and signification and, as in Barthes’ reading of Histoire de l’oeil, metaphorical values replace actual ones as one thing comes to stand for another.

Rodin, Femme à quatre pattes, vêtement relevé

The key moment in Histoire de l’oeil, in which the narrator sees Marcelle’s eye in Simone’s cunt, reflects in an instant the complete horror of gender reversal/transgression. It makes apparent male cultural fears about female subjectivity which focus on the two issues: of women seeing and their being active sexual subjects, and it does this through a too literal conflation of the two. The narrator is made into both subject and object; he is himself but he also sees through the displaced eye of Marcelle. This is a literal displacement which situates seeing/subjectivity firmly in the body. Sexual transgression and vision have been linked throughout the novel but there are important ambivalences in this climactic scene: is Simone and/or the narrator raping/fucking Marcelle’s eye? Is the eye raping them through its horrific appearance? Or are both women metaphorically raping the narrator through this literal conflation of looking and fucking, a literal ‘mind fuck’ in which his male subjectivity is threatened by female bodies.

Rodin, Femme nue sur le dos, maintenant les cuisses écartées [+ eye]

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2025 | All rights reserved

Comments