Musicology & the Guitar

I CAN SEE FOR MILES – THE WHO

John Perry

From John Perry, The Who: Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy (NY: Schirmer Books, 1998) pp: 106-117

I know you’ve deceived me now here’s a surprise

I know that you have ‘cause there’s magic in my eyes

I can see for miles and miles and miles and miles and miles

Oh yeah

If you think that I don’t know about the little tricks you play

And never see you when deliberately you put things in my way

Well, here’s a poke at you

You’re gonna choke on it too

You’re gonna lose that smile

Because all the while

I can see for miles and miles, I can see for miles and miles

I can see for miles and miles and miles and miles and miles

Oh yeah

You took advantage of my trust in you when I was so far away

I saw you holding lots of other guys and now you’ve got the nerve to say

That you still want me

Well, that’s as may be

But you gotta stand trial

Because all the while

I can see for miles and miles, I can see for miles and miles

I can see for miles and miles and miles and miles and miles

Oh yeah

I know you’ve deceived me now here’s a surprise

I know that you have ‘cause there’s magic in my eyes

I can see for miles and miles and miles and miles and miles

Oh yeah

The Eiffel Tower and the Taj Mahal are mine to see on clearer days

You thought that I would need a crystal ball to see right through the haze

Well, here’s a poke at you

You’re gonna choke on it too

You’re gonna lose that smile

Because all the while

I can see for miles and miles, I can see for miles and miles

I can see for miles and miles and miles and miles and miles

And miles and miles and miles

The Who

JOHN PERRY: AN INTRODUCTORY NOTE

RICHARD JONATHAN

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

It is my contention that John Perry’s writing on rock is the finest in the genre.1 Why? Because he excels at anatomizing a song in a way that makes our ears more sensitive, our minds more stimulated, our hearts more receptive and our bodies more attuned to the music than they were before. And, to the degree that we find the song transcendent, he elevates our souls. Rest assured, dear reader: I’ve allowed myself this touch of grandiloquence only because John Perry himself is so self-effacing. We live today in a media environment characterized by debased language and dead conventions, new technology and old fatuity, an environment in which John Perry’s writing distinguishes itself by the incisiveness of its analyses, the acuity of its perceptions and the fluidity of its style. He wears his learning lightly, but the depth of his insights is often astounding. His prose is plain-spoken, but scintillating in its effectiveness. What is particularly appealing in John Perry’s writing is the way he makes musicological analyses richly meaningful. Finally, for anyone not ignorant of the fact that John Perry was the Only Ones’ lead guitarist, you will not be surprised to find in his writing the same effortless grace that characterizes his playing, that sacred fire that aspires to the sublime.

1 – JOHN PERRY has written three books: Electric Ladyland: Jimi Hendrix (London: Bloomsbury,2004) | Exile on Main Street: The Rolling Stones (NY: Schirmer Books, 1999) | Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy: The Who (NY: Schirmer Books, 1998)

The Only Ones – Four Albums – John Perry

I CAN SEE FOR MILES – THE WHO by JOHN PERRY

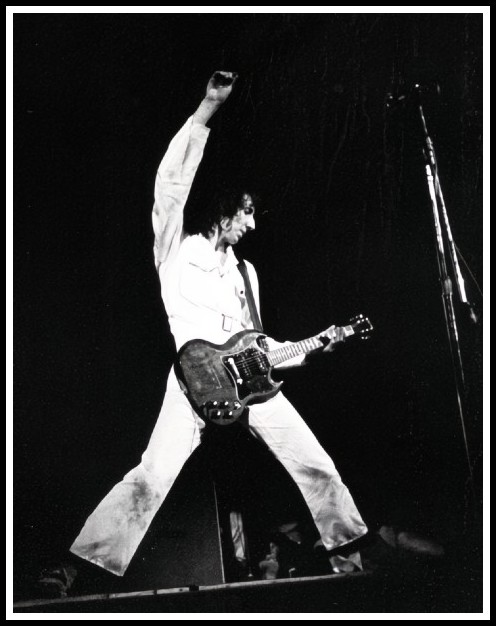

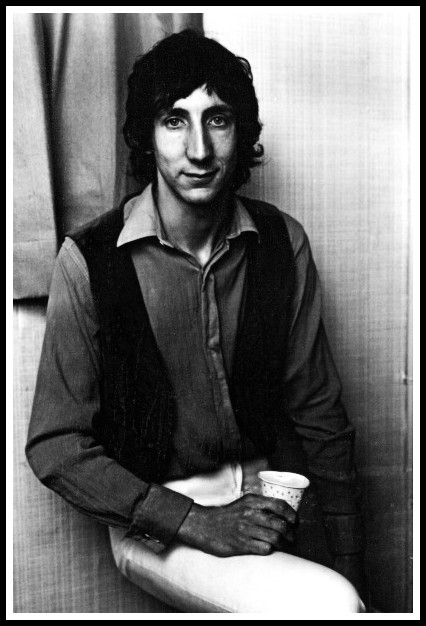

For three years, Who singles had been entering the English charts with monotonous regularity. ‘I Can See for Miles’ was the eighth consecutive hit, but none had fulfilled Townshend’s avowed aim of achieving the number-one spot, nor had any of them made much of a impression on the American chart. Convinced by now, in his own words, that he had the business of writing hits sussed, Pete pulled his best song out of the locker and focused his powers on creating the definitive Who record, one that could surely top both English and American charts.

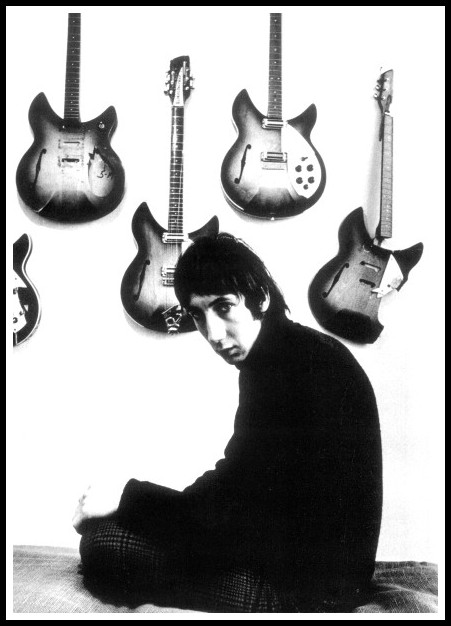

Pete Townshend

From its conception, Pete considered ‘Miles’ something special. It was his ‘ace in the hole,’ the secret weapon with which he could redeem matters if The Who were ever in deep trouble. His comment that it was written ‘probably around the same time as ‘I’m a Boy’ dates its composition to the first third of 1966, and various qualities common to the demos of both songs bear this out. Richard Barnes suggests that it could’ve been released before, or instead of, ‘Happy Jack.’ Certainly everyone in The Who camp seems to have sensed that the song was something unique, and felt a degree of trepidation about actually recording it. Pete waited for Kit Lambert’s confidence as a producer to reach suitable proportions before attempting the song, which in itself is an insight into the complex relationship between the two men. Kit’s qualities as a producer, over and above the guidance he gave Townshend at the writing stage, lay neither in musical knowledge nor recording technique, but in the ability to motivate the players, manage their excesses, and create a suitable studio atmosphere, so his own state of mind and level of self-confidence were critical. Pete told Jann Wenner that the demo ‘was just so exciting and so good that for a long time we didn’t dare make a single because it was blackmail. I was more or less blackmailing Kit Lambert into doing better. So we always put it off until Kit was very sure of himself.’

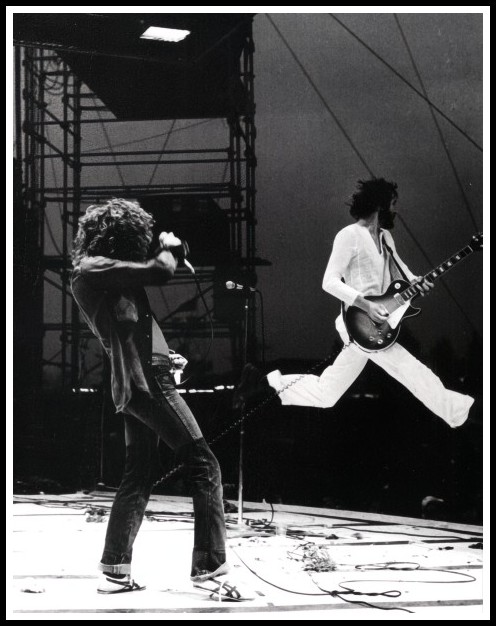

The Who

Excitement is an unstable and notoriously elusive commodity. Captured one day, it can prove impossible to repeat on another, as musicians and producers everywhere know. Like any work that relies on balancing form with spontaneity, there are times when it just won’t happen—and of course, the harder you try, the more elusive it becomes. Trying to recreate the magic of a great demo has defeated many top bands and famous producers; some parts can be reproduced with ease, but the spark that ignites them, the feel that binds them, are entities of an entirely different order—volatile, capricious, and utterly unresponsive to coaxing. A great recording is more than just the sum of its parts. When the interaction between those parts proves unrepeatable, it’s sometimes simpler to abandon the attempt and use the demo, polishing it up as much as possible. When The Jimi Hendrix Experience had finished cutting ‘Purple Haze,’ they spent twenty minutes banging down a rough take of a new song, called ‘The Wind Cries Mary.’ Try as they may at subsequent sessions, they could never recapture the ease of that spontaneous run-through, so the rough version was released, mistakes and all. There are small timing glitches—the production could not be called glossy—but the atmosphere is relaxed and intimate, and the fluid guitar lines are Hendrix at his most graceful. The record is living proof that nonchalance is damned hard work.

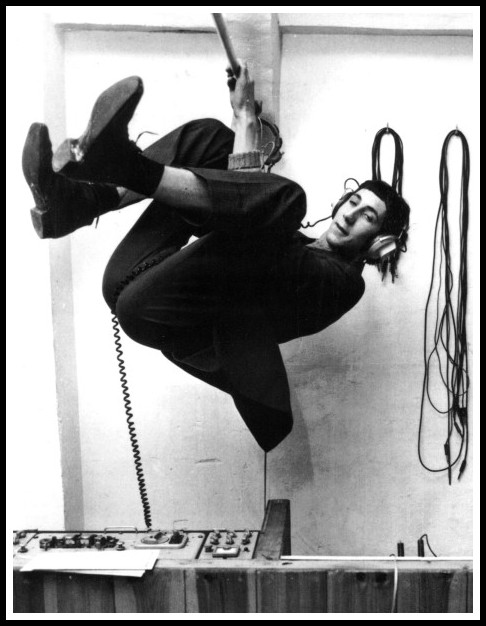

Pete Townshend

It would seem that ‘I Can See for Miles’ wasn’t attempted during the Quick One sessions of November ’66. When the band re-entered CBS London Studios in the spring of 1967, the time felt right to Kit, and the basic track was laid down. Pete recalls: One night he just turned around and said to us ‘Let’s do ‘I Can See for Miles.’ I had the demo there and we put it on and we dug it again. And he did it. He got it together. The moment was obviously propitious. The track is rich sounding, skillfully assembled, and stunningly recorded, and it must have been clear from the start that the track was happening. Atypical among Who singles, this is very much a studio record, arranged for several guitar parts, and was consequently seldom ever played onstage. Whereas ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’ tried to evoke the live performance by throwing in as much as possible, ‘Miles’ took the opposite tack, compressing the band’s onstage excitement into the grooves of a single by paring down the cardinal Who qualities to their essences. Despite multiple guitars, there’s not a superfluous note in the entire four minutes, just the vital elements precisely positioned to create an atmosphere of refined menace. The result, by miles, is the most ominous sound The Who ever recorded.

Pete Townshend

With the basic track captured at the CBS session, there was little time to develop the song. As usual, lack of funds meant that the band had to get back out on the road. Through the spring they played U.K. and Italian dates before making their long-planned U.S. debut on Murray the K’s Easter show. They came straight back to Europe to make a short German tour—in Dusseldorf, a show with fellow Track artists John’s Children turned into a pitched battle and full-scale riot—then traveled on to Helsinki, and a week in Scandinavia. ‘Pictures of Lily’ was released (prospering as always in the U.K., but, once again, failing in the U.S.), then in June the band made a second trip to the States, playing shows in Ann Arbor and San Francisco, before their vital appearance at The Monterey Pop Festival on June 18. The band returned for a brief spell back in London, during which they recorded ‘Under My Thumb’/’The Last Time,’ following the Stones’ Redlands bust, before a third, and far longer, U.S. tour from July 14 to September 16, supporting Herman’s Hermits. Finally, during a break in this tour, time was found to resume work on ‘I Can See for Miles,’ at Gold Star studios in Los Angeles.

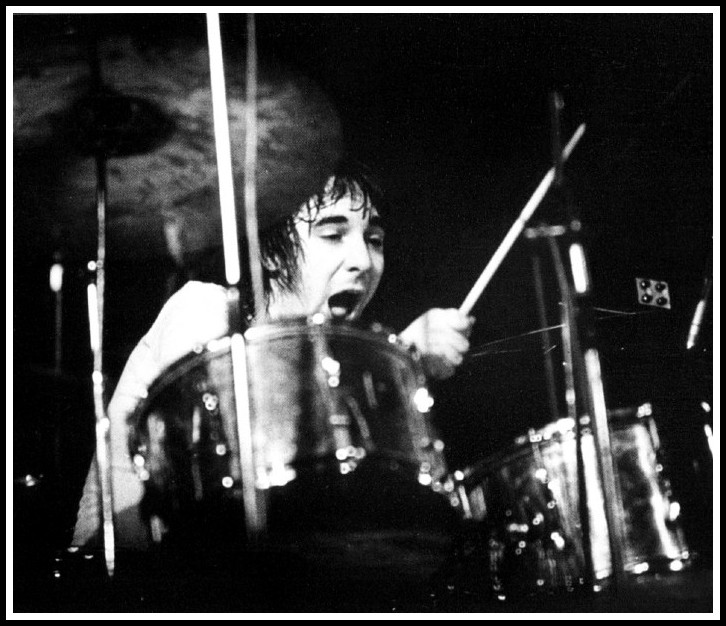

Keith Moon

The best American studios of the mid-sixties had equipment far out-stripping their English counterparts and engineers with greater experience recording rock music. The Stones had been taking advantage of U.S. tours since ’64 to record with engineers like Ron Malo at Chess and Dave Hassinger at RCA Studios in Hollywood; the results, including ‘It’s All Over Now,’ ‘The Last Time,’ and ‘Satisfaction,’ speak for themselves. In the U.S., The Who discovered a new depth and clarity of sound. Gold Star was the studio in which Phil Spector had produced his ‘little symphonies for the kids,’ and was known to possess an enchanted echo chamber. Pete describes his enthusiasm for the studio: We cut the tracks in London at CBS studios and brought the tapes to Gold Star studios in Hollywood to mix and master them. Gold Star have the nicest sounding echo in the world. And there is just a little of that on the mono. Plus, a touch of home-made compression in Gold Star’s cutting-room. I swoon when I hear the sound. Even the best recorded tape can still go wrong in the mastering or pressing, which are the final stages of record production. Many a well-recorded tape has gone down with all hands. ‘Miles,’ however, was safely delivered onto vinyl in time for an October release.

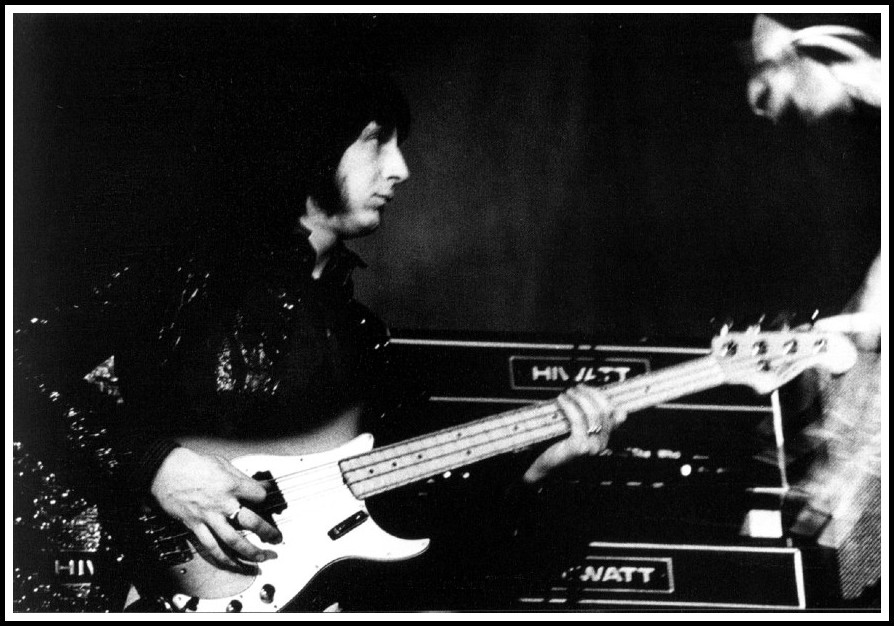

John Entwistle

Inevitably, the most beautifully arranged and recorded single in The Who canon—the certain hit held back for an emergency failed to sell anything like the quantities expected. Townshend was infuriated, then despairing. Like Spector, after his Gold Star masterwork ‘River Deep, Mountain High’ failed to crack the U.S. charts, Pete withdrew from the singles arena, expressing disgust with the stupidity of the record buying public. He told Ray Tolliday: To me this was the ultimate Who record and yet it didn’t sell. The day I saw it was about to go down, I spat on the British record buyer. The relative failure of ‘Miles’ signaled the end of The Who’s days as a pop group. Eight singles, spanning March ‘65 through November ‘67, starting with their debut ‘I Can’t Explain’ and ending with ‘I Can See for Miles’ had each entered the top-10. The unbroken run stopped there. On the English chart, ‘Miles’ only reached number 10. It wasn’t that the record was a miss, just that expectations for it had been so high. The Who had never had a number 1 and Townshend, justifiably confident in his own writing ability, had clearly set out to score one with this single. Unbelievably, a record which managed to create a perfect balance between the excitement of hard rock and the catchiness of a mainstream pop single, the distillation of everything The Who had set out to do on 45, achieved the lowest chart showing thus far—equaling ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere,’ though even that record stayed six weeks on the chart while ‘Miles’ only lasted for four, the shortest duration of any of the singles.

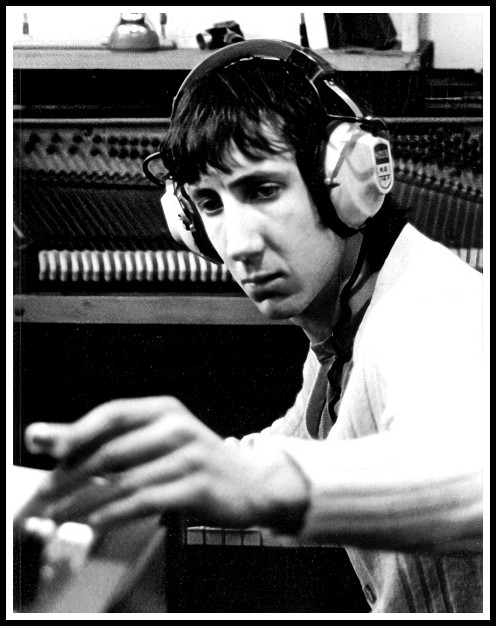

Pete Townshend in his home studio

Yet in America ‘Miles’ was the first Who single to do any serious business, and the first to enter the top-10. It reached number 9 and stayed five weeks on the Billboard chart. However, even this long-awaited U.S. breakthrough failed to alter Townshend’s perception of the record as a flop, though it permanently altered everything else. The Who’s priorities changed. The sustained American touring in the summer had certainly prepared the way for ‘Miles’ to enter the top-10, and from this point (October ’67) they turned their full attention to the pursuit of success in America.

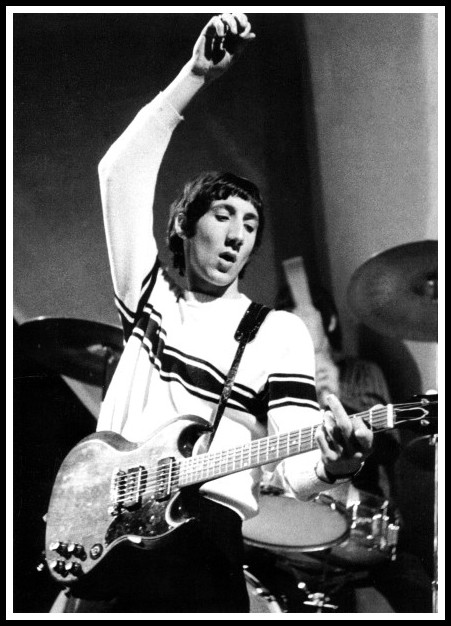

Pete Townshend

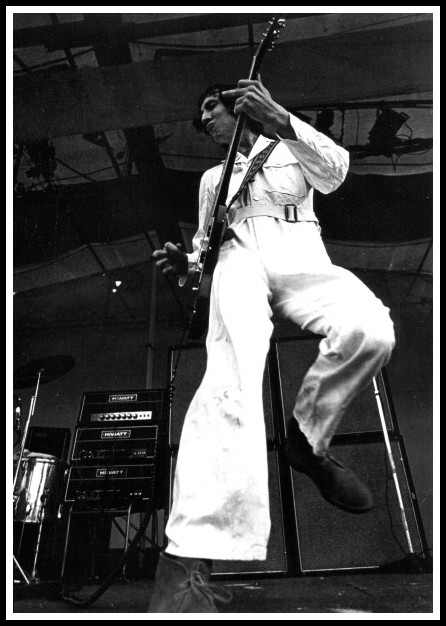

In 1966 The Who were probably the loudest thing that anyone outside of artillery circles had ever heard. But anyone can play loudly. What distinguished them from the myriad thumpers who followed them was their intelligent use of dynamics. As a unit they recognized that effective live performance is all about expansion and contraction, tension and release; that triple fortissimo is more effective when it follows a passage of quiet; that contrast is more powerful than relentless sledgehammering; and they possessed the musicality and ensemble understanding to deploy that insight. From early in their career they used light and shade to greater effect than any of their rivals. Their live trademark—the ominously steady passage that suddenly erupted into overpowering crescendo—is brought to perfection on ‘I Can See for Miles.’ Abrupt rushes of guitar jump out from simple pedal bass parts, the drums sound more like a bombing raid than an exercise in timekeeping, and Daltrey’s vocal strikes the exact tone of cold superiority implicit in Townshend’s lyric. Gone are the sprawling, lashing, tongue-tied Who, stuttering in frustration at the inability to articulate their rage, replaced by an altogether cooler, more focused proposition, in which detachment, clarity of vision, and a nicely controlled violence converge with such precision that the actual threat never needs to be expressed.

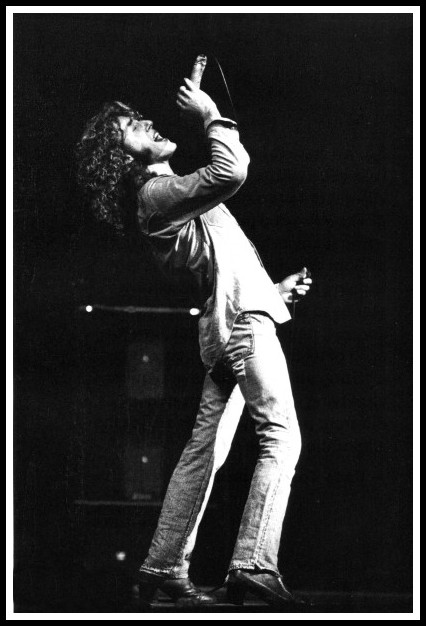

Roger Daltrey & Pete Townshend

The spareness of the arrangement allows the listener to hear how good the individual instruments and voices sound. The instrumental sound is so clear, the quality of the arrangement is revealed. The overall effect is lean and concise. The bass pumps away unchanged on a single note, creating a flat plain on which the action occurs. For most of the song, Entwistle’s eight-to-the-bar pedalled E underpins the changes, even where the sequence moves through four or five different chords. One of Pete’s guitars doubles this part. The atmosphere is tense but unhurried. It builds in its own time. After Townshend’s opening chord, nearly two bars pass before anything else happens. Then, at the seventh beat, Moon comes in with an introductory drum fill and proceedings begin. The slow buildup throughout the track is beautifully managed, with new elements introduced as the song progresses. Unlike, for example, ‘Pictures of Lily,’ which is basically a live performance with fixed instrumentation, ‘Miles’ obeys Keith Richards’s precept that a hit single should feature ‘something new every ten seconds.’ The stereo mix gives much better separation, presenting a clearer picture of the disposition of Pete’s three guitars—two electrics and an acoustic. The two main guitars, panned hard left and right in the stereo image, conduct a dialogue, alternate lines, and suspend mildly dissonant chords, while the acoustic adds an almost subliminal presence.

Pete Townshend in his home studio

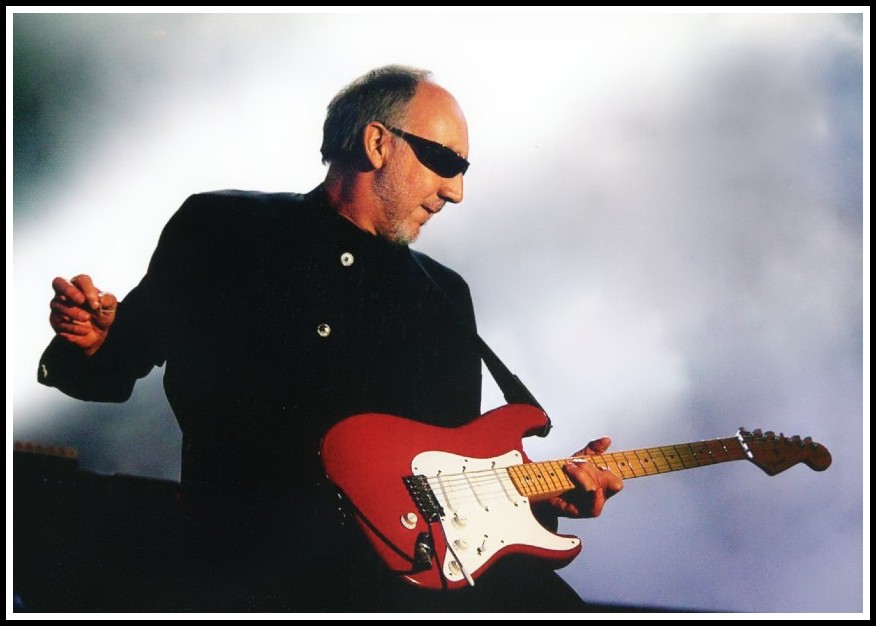

Perhaps my favorite guitar moment in the song comes at the final chorus. The nagging unison bend on E that runs through the penultimate chorus suddenly leaps up an octave (at 3’51’) and plays to the fade. It’s simple and effective. (A unison bend is played by holding a note on one string, while bending an adjacent string upward, until both strings are at the same pitch. As the near-unison slips in and out of phase, the result is a sharp, stinging tone.) Townshend was never technically dazzling in the Hendrix/Beck mould— ‘when I should have been practicing I was writing songs, and when I was writing songs I should’ve been practicing’—but more than any other guitarist of his era he learned to make a virtue of his limitations. Simple devices such as the octave leap described above are placed to great effect within the context of the songs. Frustration at his relative inability also produced the power chord, which forces maximum expression from the simplest of components. Before 1968, Townshend rarely attempted lead breaks, preferring to let other instruments take the solos, such as the bass on ‘My Generation’ and ‘Substitute,’ the horn on ‘Pictures of Lily,’ and harmony vocals on ‘I’m a Boy.’ Or, if he did play, he used noise and effects as on ‘Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere’ or a chord solo as on ‘Happy Jack.’ For ‘Miles,’ he came up with a device perfectly suited to the uncompromising mood of the song: a one-note solo. A single mid-range E is hammered out at the tempo of a pneumatic drill, then finished up with a quick one-handed trill. Once heard, it’s so obviously right, you know that nothing else would do.

Pete Townshend

Every instrument has keys that suit it and keys that don’t. ‘I Can See for Miles’ is in the key of E, a classic guitar key that allows use of the lowest note the instrument can produce in normal tuning. It gives a song a ‘grounded’ feeling. Interestingly then, the demo was recorded in F sharp. Given the verse progression and the layout of the guitar neck, this makes sense, though once the low pedal bass is introduced, E makes better sense. Possibly too, the key was shifted to accommodate Roger’s range. A potential problem is worked around in third verse, where the song has changed key to A. The stop-time section, beginning with ‘Here’s a poke at you,’ which worked fine in the first two verses with Roger going up, is now too high, so he drops down to deliver it.

Roger Daltrey

Most songwriters, even the very best, have three or four basic songs—templates, if you will—to which they return; not from laziness, nor as any conscious reworking, but because these are the core forms on which their musical sensibilities rest. Townshend has his ‘home’ keys—first position Ds and As, useful for their chiming tone, distinctive character, and the ease with which open strings can be left ringing through the changes—as well as his favored arranging devices, but the songs themselves are amazingly diverse. One of the most impressive things about the first run of singles, which ends here with ‘Miles,’ is the consistent variety of the material. The similarity of ‘All Day and All of the Night’ to ‘You Really Got Me,’ of ‘I Can’t Help Myself ‘ to ‘It’s the Same Old Song’ finds no echo in Townshend’s writing. Amazingly, given this much diversity, not one of the songs is in a minor key—perhaps the simplest, most obvious variation Townshend could have employed to create a new atmosphere. To generalize, minor keys convey a sense of sadness, or distance. Yet even setting out to write a song as intentionally downcast as ‘Melancholia’ (an out-take from the Who Sell Out album), Townshend uses a major key.

Pete Townshend

There isn’t one song in a minor key on MBBB1; as far as I know, Townshend has never indicated why this might be, though his guitar style offers a clue. The basic chord has a bottom, a middle, and a top—the 1st, 3rd, and 5th notes of the scale, respectively—and like a sandwich, the note in the middle (the 3rd) gives the chord its flavor. It also determines whether the chord is major or minor. Instinctively it would seem—I didn’t start to actually understand the fundamentals of music until I started playing the piano and I didn’t start playing until I was 22—the young Pete Townshend settled on a way of voicing guitar chords so that they used only the 1st and the 5th. Omitting the 3rd gives a starker, tougher sound than the standard chord by removing the melodic, sweetening element. It’s other effect is to preclude minor chords: no 3rd, no minor. This construction crops up all through Townshend’s work. Instead of playing, for instance, a standard G triad (1st, 3rd, 5th—G, B, D) he stacks up 1sts and 5ths so the chord consists solely of the notes G, D, G, D, G. It’s only two notes—G and D. Even though I know it’s only got two notes in it, I can hear another note in there. It doesn’t sound like two notes. The distortion throws in other notes. A good place to hear it uncluttered is the lone D chord (D with no 3rd) which opens ‘The Kids Are Alright.’ Pete comments: If you’re playing what are two-note chords in octaves it leaves you freer melodically and it takes you back to more ancient music principles. It’s almost like using a chord as a drone.

1 – Meaty, Beaty, Big and Bouncy

Drones are found in early music, in plainsong, and in ethnic music all over the world, from Scotland to China. The bagpipes are a perfect example. The most common drone uses two notes, the 1st and 5th measures of the scale. Twentieth-century popular songwriting, by contrast, is built around the entirely different notion of chord progressions. Drones became slightly more common in popular usage after John Coltrane grew interested in Indian music around 1960 (and, as a result, directly influenced, among others, The Byrds and The Doors) and overwhelmingly more common after 1966, when people heard the Beatles use of the sitar on ‘Norwegian Wood’ and on Revolver. Townshend’s adaptation, however, sounds entirely instinctive, rather than copied from any of the obvious sources; the sort of quirk that self-taught musicians often develop, as much by accident as design.

Pete Townshend

In a way it’s fitting that the record that ended The Who’s first era should come at a time when the supremacy of the 7-inch single was passing to the 12-inch LP. Before long, the whole nature of the music business would change as the companies realized that albums were more lucrative than singles. In England, the record stands too as a fitting epitaph to pirate radio, which was put off the air in mid-August 1967. No band had been better served by, or identified more with, pirate radio than The Who. The Who Sell Out album, which features ‘I Can See for Miles,’ was conceived as a tribute to pirate radio, and especially to Radio London, with the tracks (on the first side at least) being linked by imitation commercials and ‘Big L’ jingles. In a precursor to the whole 1990s sampling squabble, The Who were later sued by the company who had originally created and supplied the jingles to Radio London. Nik Cohn approved the album’s ‘obvious reaction against the fashionable psychedelic solemnity,’ but complained that the concept was only half-completed, something which he identified as a traditional Who failing. Though ‘I Can See for Miles’ was a U.S. hit, the album only reached number 48, and got no further than number 13 in England. Its U.S. release in December ’67 marked the end of the era of the Who as Britain’s classic singles band.

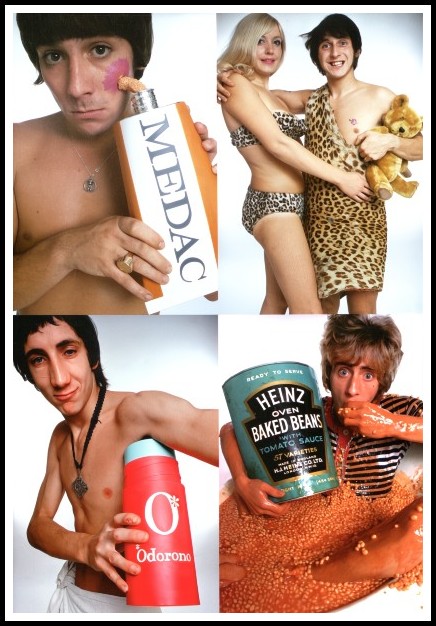

The Who Sell Out

Though the changes would take several years to work through, here was the moment when the paradoxical, embattled, melodic, quirky, constantly gigging English ‘pop group’ changed course, eventually becoming a multinational, mid-Atlantic, stadium-filling success story on the grand scale. Much was gained, but a good deal was lost too—and they would never again make singles as powerful as ‘I Can See for Miles.’

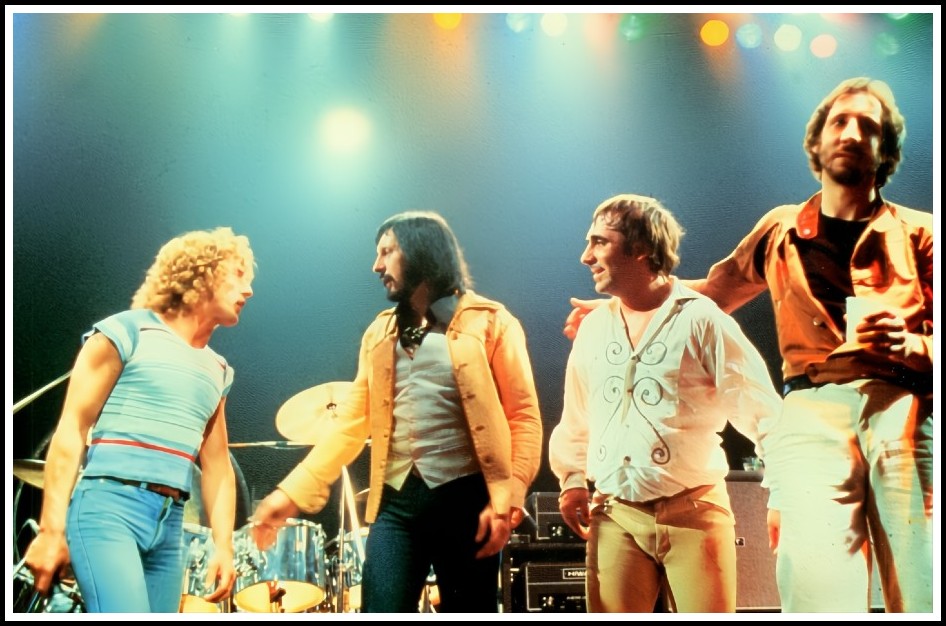

The Who – Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle, Keith Moon, Pete Townshend

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments