The Ear in the Text: John Berger’s To the Wedding

TO THE WEDDING by JOHN BERGER: ANALYSIS – AUDITORY STYLE

Ralf Hertel

RALF HERTEL IS PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF TRIER, GERMANY

From Ralf Hertel, Making Sense: Sense Perception in the British Novel of the 1980s and 1990s (Rodopi, 2005) pp. 72-83

John Berger’s novel To the Wedding exemplifies what I would like to term an auditory style. What is it that makes it a good example of this style? Tsobanakos, a blind seller of tamata, metal votive plates, tells us the story of Ninon, a French girl of twenty-four who learns of her fatal AIDS-infection from an earlier one-night stand. Despite this topic, the book is essentially a love story. Ninon’s boyfriend Gino, an Italian fisherman and seller of T-shirts at the local market, does not leave her because of her disease. Instead, believing that they have to live every moment to the full, he eventually even proposes to marry her. Their wedding, which is described in the ultimate pages of the novel, is the climax towards which the whole narration seems to aspire, and the power of their AIDS-defying love manifests itself in the rituals of the celebration. Their final wedding dance, however, is also a dance of death: descriptions of the dance alternate with visionary paragraphs relentlessly depicting Ninon’s bodily decline and her eventual death.

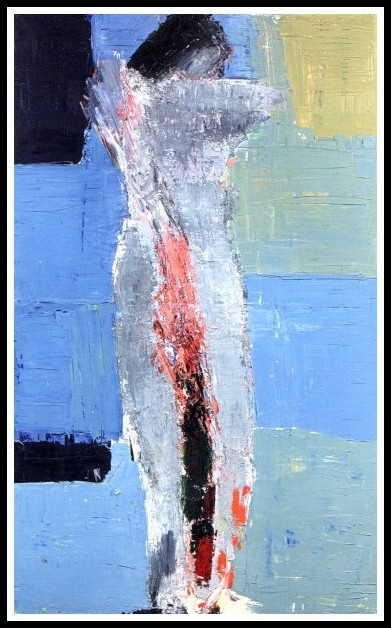

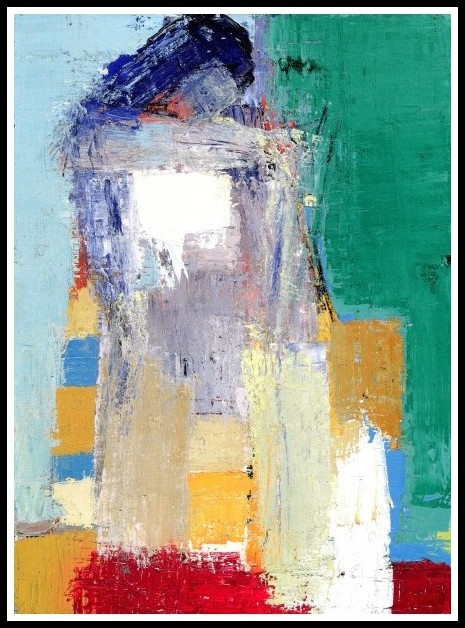

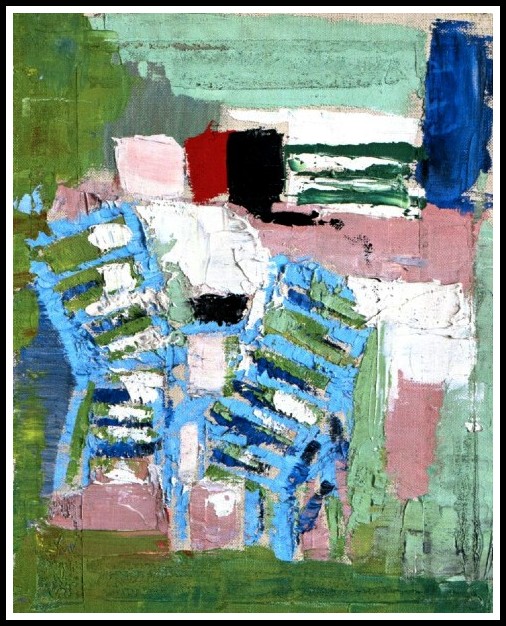

Nicolas de Staël, Nu debout, 1953

However, the ontological status of the story remains unclear. Time and again we encounter hints that the narrator Tsobanakos is merely making up the whole story. After a careful reading, one has the feeling that the only thing really taking place is an encounter between Ninon’s father Jean Ferrero and Tsobanakos, in which Jean buys a tama of a heart from Tsobanakos in the vain hope that this will make his daughter better. Ninon joins them to show her father her new sandals: ‘My new sandals — look! Handmade, Nobody would guess I’ve just bought them. I might have been wearing them for years. Maybe I bought them for my wedding, the one that didn’t take place’. It appears that from the sound of Ninon’s voice and the few words of information Jean gives when buying the tama—that it is for his daughter, that she is suffering everywhere, that she cannot recover — Tsobanakos constructs an alternative story, a story in which Ninon’s wedding does take place—the AIDS-defying love story we read. Listening to Ninon’s voice, he sees ‘slices of melon carefully arranged on a plate’, anticipating the wedding feast, in which melons are mentioned repeatedly and Scoto ‘who sells only watermelons and listens to them as if they were oracles’ figures as a guest.

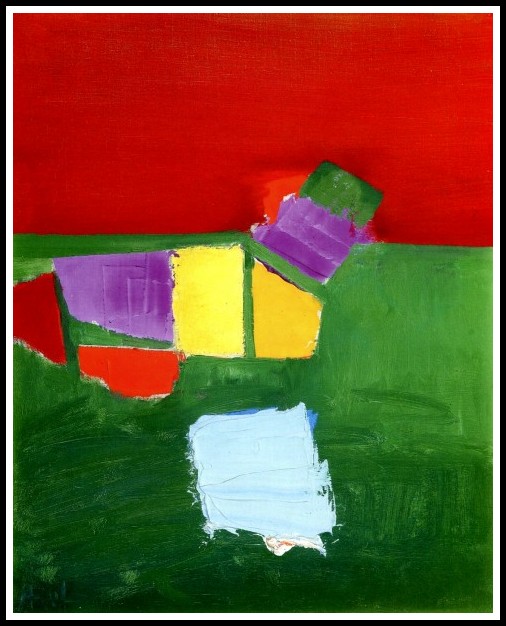

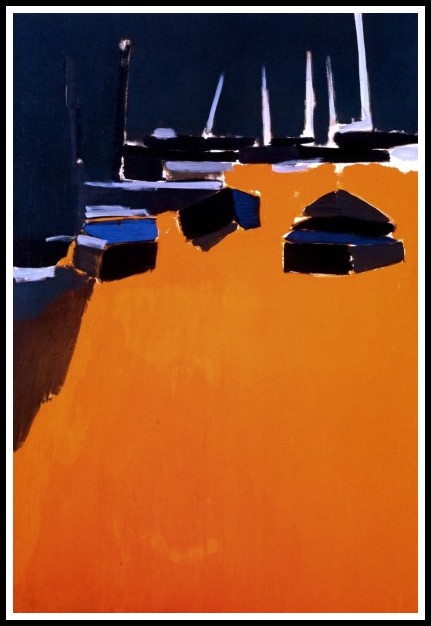

Nicolas de Staël, Indes galantes, 1953

Again and again, Tsobanakos presents Ninon’s story as a vision or, to be more precise, as an auditory apparition; it is as though ‘the blind storyteller literally “hears” the novel’.1 The whole narrative seems to take place inside his head as if he was hearing the voices of the protagonists in a waking dream. Waking up in the morning, the blind narrator suddenly hears ‘Ninon’s voice as sharply as if she had climbed up a ladder from the street and was sitting on the windowsill’; hearing a man’s laughter at the hairdresser’s, he imagines it is the laughter of Gino’s proud father; standing at the bar of his friend in Piraeus, he hears a drunken voice and imagines someone was swearing at the AlDS-infected; and hearing ‘a glass object being polished’ transports him in his imagination into the perfume department of a store in which Ninon’s father is looking for a wedding gift.

1 – ‘John Berger’, Contemporary Novelists, ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer (USA: St. James Press, 2001) p. 101

Nicolas de Staël, Indes galantes, 1953

What is more, at the moment of narration, the wedding has not yet taken place and it remains uncertain whether it will take place at all, especially if one keeps in mind Ninon’s opening remark about the wedding ‘that didn’t take place’.

The wedding in Gorino hasn’t taken place yet. But the future of a story, as Sophocles knew, is always present. The wedding hasn’t begun. I will tell you about it. Everybody is still asleep. | The sky is clear and the moon almost full. I think Ninon, staying in the house of Gino’s aunt Emanuela will be the first to wake, long before it is light. She will wrap a towel round her head like a turban and wash her body. Afterwards she will stand before the tall mirror and touch herself as if searching for a pain or blemish. She will find none. She holds her turbaned head like Nefertiti. (p. 172)1

1 – John Berger, To the Wedding (London: Bloomsbury, 2009 [1995)) p. 172. All citations from the novel are from this edition.

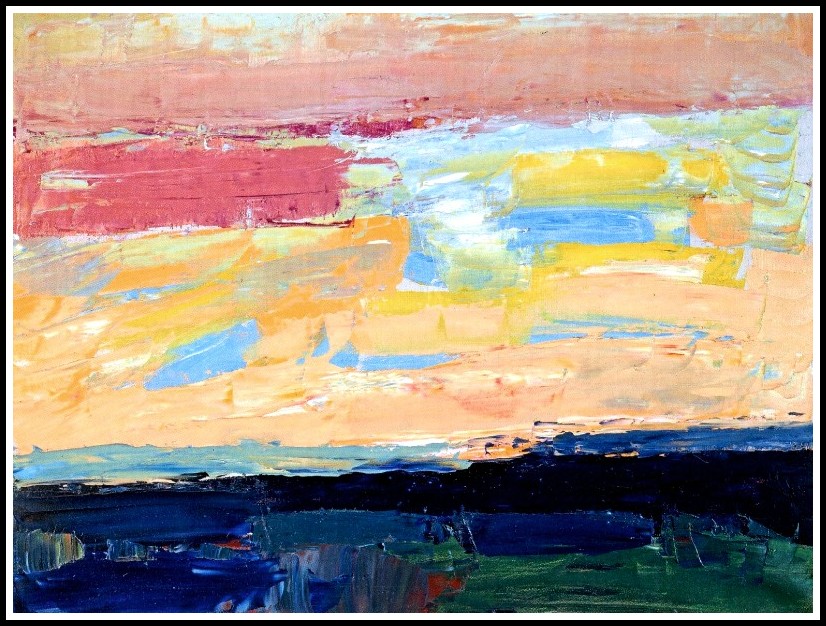

Nicolas de Staël, Nu debout, 1953

The whole wedding day appears to be a vision, an effect that is not least caused by the frequent use of the future tense. Although the narrator makes use of the present tense from time to time, presenting the wedding as an event actually taking place the same instant as he narrates, he constantly reverts to employing the future tense, reminding us that all he describes about the wedding feast and the outbreak of Ninon’s disease is merely a vision. Added to the highly associative, dream-like quality of his auditory perception, this nourishes the suspicion that the entire story, like the wedding which is its climax, ‘hasn’t taken place yet’ and is purely imagined. No matter how convincing Tsobanakos’ story of the love between Ninon and Gino might be, no matter how realistically some details such as their crossing of the river Po might be rendered—doubts emerge about the ontological status of the story. The novel hovers between fact and fiction and can at no point be completely ascribed to either side.

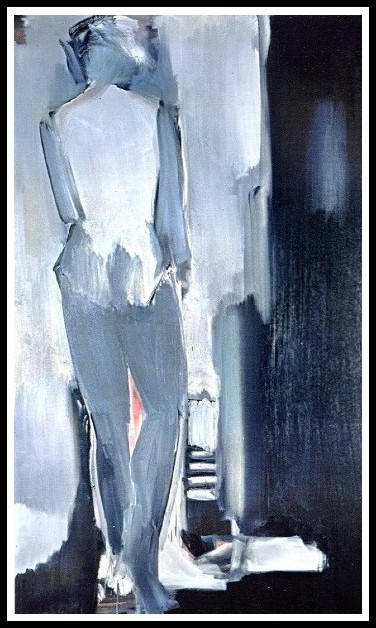

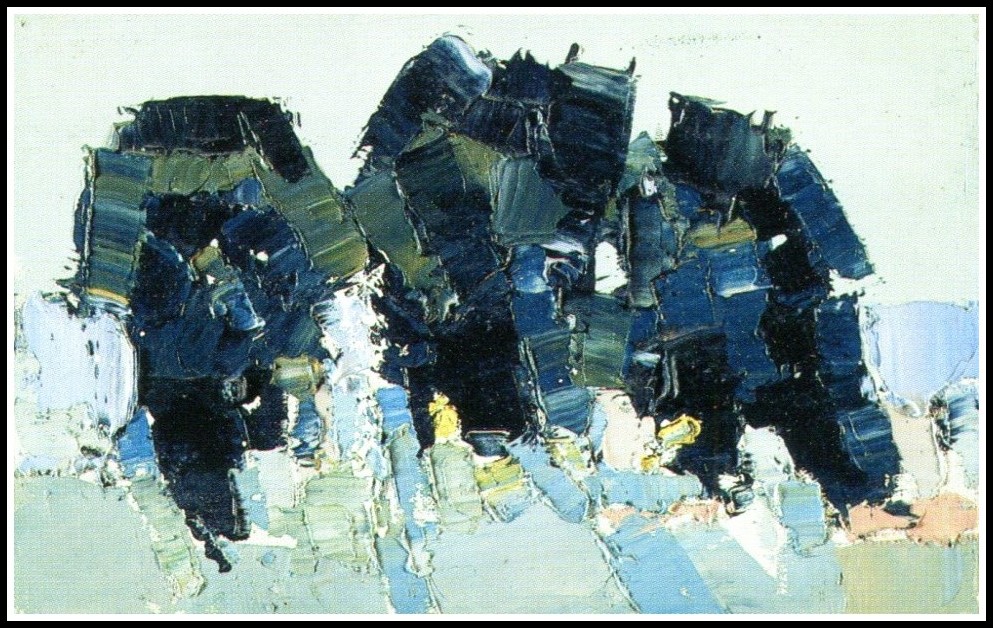

Nicolas de Staël, Nu gris vu de dos, 1954-55

This instability of status, this dynamics of fact and fiction is mirrored in the title that, first of all, suggests movement: towards the wedding. Indeed, great parts of the novel consist of the description of the journey of Ninon’s separated parents to the wedding in Gorino, a small village at the confluence of the river Po and the Mediterranean Sea. Ninon’s father Jean, whose last name Ferrero alludes to his occupation as a railway signalman (French ‘fer’ meaning ‘iron’, ‘chemin de fer’ railway), comes from the west: he rides his motorbike from his home town Modane in southern France across the Alps, following the Po until he arrives in Gorino. Ninon’s mother Zdena Holecek approaches from the east: she takes a coach from Bratislava to Venice and changes there to a boat that brings her to the wedding venue. Thus, the wedding is a climax in more than one sense: not only does it unite Ninon and Gino as a couple, but it reunites Ninon’s parents after nineteen years of separation, at least temporarily, too.

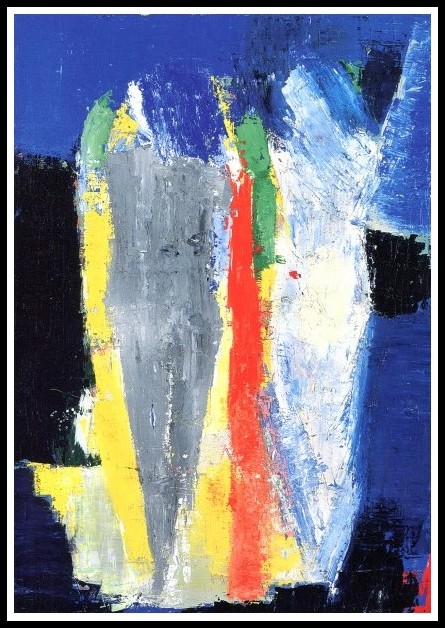

Nicolas de Staël, Figures, 1953

Indeed, the entire party of wedding guests seem to fuse into ‘a single animal’:

A strange creature to find in a widow’s orchard, a creature half mythical, like a satyr with thirty heads or more. Probably as old as man’s discovery of fire, this creature never lives more than a day or two and is only reborn when there’s something more to celebrate. Which is why feasts are rare. For those who become the creature, it’s important to find a name to which it answers whilst alive, for only then can they recall, in their memory afterwards, how, for a while, they lost themselves in its happiness. (p. 186)

The wedding cake provides them with this name: GINON is written on it, graphically demonstrating the merging of hitherto separate individuals: ‘And this becomes forever the name of the thirty-headed creature in the orchard’ (p. 186).

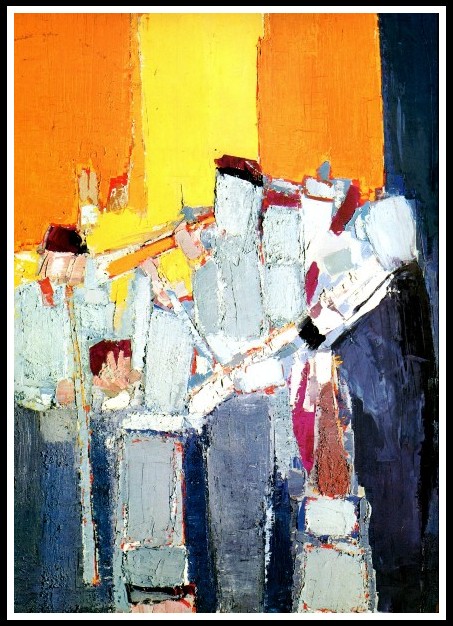

Nicolas de Staël, Les Musiciens, 1953

More technically speaking, the wedding is also a fusion of the various narrative threads of the story. The moment Ninon’s parents arrive at the wedding, the plot of the love story is finally united with the subplots of her parents’ respective journeys. Eventually, even the narrator Tsobanakos himself turns into a character within the story he tells: ‘With my white stick I wander among Gino’s friends and feel at home’ (p. 175). Thus, in this climactic wedding feast, even the narrative frame is fused with the plot itself—the final, ecstatic dance is nothing but an apt symbol of this ultimate fusion.

Nicolas de Staël, Figure debout, 1953

If movement is crucial to the novel’s plot, this is reflected in its structure: fragmented, associative, and disruptive, it defies any rigid chronological or geographical order. Instead, the story’s progress appears to be erratic. The uncertainty of the ontological status of the story is mirrored in an uncertainty of viewpoint; the narration constantly jumps from one plot to another, incessantly alternating the voices of Tsobanakos, Ninon, Gino, his father Federico, and several others, all of whom figure as first person narrators as the story unfolds. If the title suggests movement, the anti-static structure makes the reader constantly recreate it in the act of moving from viewpoint to viewpoint. It is a highly associative structure, as if the blind narrator were overhearing parts, sentences, single words of various conversations, or merely the sound of a voice and these then sparked off his imagination.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

Apart from the laughter mentioned that makes him imagine Gino’s proud father Federico, and the sound of ‘a glass object being polished’ (p. 153) that transports him into a perfume department, there are other sounds that incite his imagination. He hears an ‘old woman’s voice’ (p. 65) that makes him imagine Jean taking a rest on his motorbike trip across the Alps, meeting an old woman talking to him about her husband (p. 61). Later, after a visit to his friend Yanni’s bar, he stands on a platform in the railway station in Piraeus, having missed his last train back to Athens (p. 136). Hearing the loudspeaker announcements, he sees himself in Bratislava, looking for Zdena who is about to leave for her daughter’s wedding (p. 122). Right at the beginning of his narration, Tsobanakos explains: ‘Voices, sounds, smells bring gifts to my eyes now. I listen or inhale and then I watch as in a dream’ (p. 7). This seems to be Tsobanakos’ narrative strategy: having to make do without the sense of sight, he relies entirely on his olfactory and especially on his auditory perception. These stimuli then set his imagination going, which creates for the inner eye what his actual, blind eyes can no longer perceive.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

If a narrator depends so heavily on his sense of hearing as blind Tsobanakos does, it comes as no surprise that auditory impressions should influence his narration to a high degree. Indeed, To the Wedding is characterised by a structure that at times seems to actually simulate auditory perception by means of literature. Through its incessant shift of viewpoints, the novel confronts us with a multitude of speakers. Tsobanakos is clearly the narrator, yet his presence is often not felt and his voice gives way to those of the characters in his story. At first, the voices of Tsobanakos, the Greek seller of votives, Jean, the French signalman, Zdena, the Slovakian encyclopaedist, Federico, the Italian scrap merchant, and all the others seem to have little in common and appear disjunctive. As the novel unfolds, though, it emerges that they all belong to people who are on their way to the wedding. Eventually, the voices merge in the ecstatic feast, turning the initial vocal cacophony into a polyphony—or rather into the single voice of that strange, many-headed creature called GINON that the wedding guests have become.

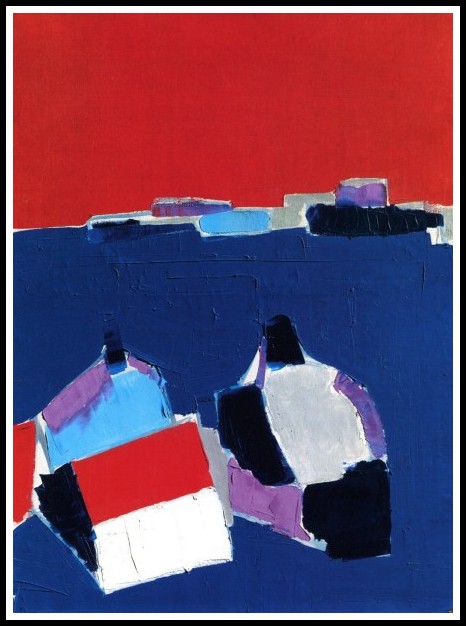

Nicolas de Staël, Composition sur fond rouge, 1951

In dialogues, speech markers like ‘he said’, ‘she argued’, or ‘I replied’ are often absent, and quotation marks are frequently omitted. The narrator lets words and voices stand for themselves; as a mediating instance, he retreats almost completely behind the dialogues. Thus, the characters’ voices become present; we hear them as if we were hearing with Tsobankos’ own ears. Sometimes it becomes difficult to tell whether we are listening to the protagonists or to the narrator’s inner voice conjuring them up. Furthermore, the shifts of perspective become more and more rapid as the novel progresses. Paragraphs often consist of merely two or three sentences, and changes of perspective might take place at breath-taking speed. The following passage contrasts the voice of Ninon learning of her AIDS- infection with that of Tsobanakos narrating her father’s journey to the wedding.

I phone Marella and I ask her to come round. I have to talk. I tell her what’s happened. Christ! she says.

After he has crossed the bridge, the signalman stops, puts both feet down and looks up at the sky, his arms hanging limp.

This morning when I woke up I didn’t remember. For a few seconds. For a few seconds I forgot. I didn’t remember. Dear God.

The signalman grips the grips, revs and taps down into first. I have a rendezvous with Gino in Verona and I shan’t go. No. Never.

The signalman has disappeared behind a reed bank, driving fast now, as if he has changed his mind about something. (p. 76)

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

The two voices follow each other so rapidly that it seems as though both events are taking place at the same time, as if we hear Ninon and Tsobanakos speak simultaneously. Both events seem to respond to each other, even though, according to the logic of the story, Jean’s trip to the wedding can only take place after Ninon realizes that she is infected. Yet, Jean’s gesture of utter despair—stopping the motorbike, looking up at the sky with arms hanging limp—suggests an unconscious response to Ninon’s discovery of her fatal disease. Again and again, separate narrative threads are linked in a similar way: the sound of a piano makes Tsobanakos think of a nocturne being played from a CD at Zdena’s flat in Bratislava, the laugh at Tsobanakos’ hairdresser’s makes him envision Gino’s father and reoccurs when Jean is stopping for a cappuccino in Turin, the sigh Zdena lets out while, thousands of miles away, her daughter unknowingly contracts AIDS from her infected lover. All these subtle links help to establish a feeling of simultaneity: it is as if everything happened at the same time.

Nicolas de Staël, Portrait d’Anne, 1953 (detail)

This simultaneity, however, imitates the way in which Tsobanakos must encounter the world. Relying almost completely on his sense of hearing, his perception must be essentially synchronous. For while the visual sense can be selective—we focus on something, we look away, we close our eyes—the auditory sense is fundamentally indiscriminate. Unless we block our sense of hearing completely, it registers all sounds, whether pleasant or not. As Walter Ong observes, ‘sound situates man in the middle of actuality and in simultaneity, whereas vision situates man in front of things and in sequentiality’.1 The narration imitates this auditory perception through its structure of concurrence and thus conveys to us a feeling for Tsobanakos’ view—or rather hearing—of the world. ‘Berger deftly turns the reader into a ‘listener of voices’, making him experience the story as if he were blind—hearing voices rather than consciously reading letters on the page.’2

1 – Walter J. Ong, The Presence of the Word: Some Prolegomena for Cultural and Religious History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1967) p. 128

2 – ‘John Berger’, Contemporary Novelists, ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer (USA: St. James Press, 2001) p. 101

Nicolas de Staël, Grignan, 1953

A few examples shall suffice to demonstrate that—apart from structural devices—Berger employs a wide variety of rhetorical means in order to create this illusion of the auditory. The general tone of the novel, for instance, imitates the simplicity of oral speech: ‘This morning when I woke up I didn’t remember. For a few seconds. For a few seconds I forgot. I didn’t remember. Dear God.’ Ninon’s few words abound with markers of orality: her sentences are short, in fact, two of them even lack a verb; they are redundant (‘I forgot. I didn’t remember’), show a repetitive, cumulative structure (‘For a few seconds. For a few seconds I forgot’) and demonstrate an emotional involvement that is characteristic of oral speech and often lost in the more distanced literary style (‘Dear God’). Yet, it is not only the passages of direct speech that show markers of orality. Narrative descriptions of scenes such as Jean’s journey through the Alps or the wedding dance also demonstrate references to an oral style.

Gino and Ninon will be the first to dance. Soon other couples join them. The music is loud. It brings the village to the square. The waiters serve wine. Federico is organizing a game of leapfrog on the grass for the youngest kids. The sun is low in the west, and more and more people dance on the deck: a platform of planks which has been laid on the square in front of the band so that the dancing floor is level. The boards were borrowed from the fish market in Comacchio. There are many spectators, including a man in a wheelchair. Only when Gino and Ninon are lost in the crowd does the music come close to them. (p. 193)

Nicolas de Staël, Martigues, 1954

The simple, paratactic style evokes oral storytelling: one thing after another, lest anything should be lost in a sub-clause and forgotten. The sentences are deliberately short, as if they were spoken for a listener who has to understand everything at once, rather than being written for a reader who can reread a sentence or return to something mentioned earlier. The predominant use of the present tense throughout the novel further underlines this emphasis on the immediate moment: all temporal distance is lost. Most of what we see and hear—not only in the wedding scene—takes place in the present tense as if it were happening at the moment of narration. It is as if Tsobanakos, the narrator, was actually there among the characters of his story—and indeed, during the wedding he finally ‘wander[s] among Gino’s friends and feel[s] at home’, as we have seen (p. 175). To the Wedding creates the illusion that we are not so much reading a literary work but listening to the narrator’s voice, a feeling underlined by the repeated addresses of the narrator to his imagined audience (e.g. pp. 5, 40, 172). Tsobanakos speaks to us as if to someone listening, and we see the story through his eyes, or, rather, we hear it with his ears—the blind narrator Tsobanakos becoming the reader’s ear within the text.

Nicolas de Staël, Agrigente, 1953

Yet, what is the purpose of this auditory style? With its free associations, its deliberately loose and anti-static structure, its freedom of viewpoint, its egalitarian polyphony of voices, and a carpe-diem-like emphasis on the present moment, it enacts the novel’s underlying theme of liberation. For indeed, To the Wedding is not so much about AIDS as such but rather about the possibilities of living—and loving—in the face of this fatal disease, demonstrating how to overcome, at least partially, approaching death through love. Several motifs subtly anticipate the liberating power of love. The journeys of both Jean and Zdena lead them across the Alps towards the sea: they cross the mountain barrier and move towards the open, endless space of the seaside. On the mountain roads, they can see no further than the next bend, the next wall of stone; they appear to be caged. They move on into the open, however, and reaching the seaside, their horizons widen into infinity. It is as if they have been caught in the prejudices and taboos society places upon AIDS but have then overcome this narrowness of mind. Reaching the wedding, they can see further now, realizing that everyone has to die and that AIDS is simply another form of a memento mori, a disease that heightens the sense of the present moment.

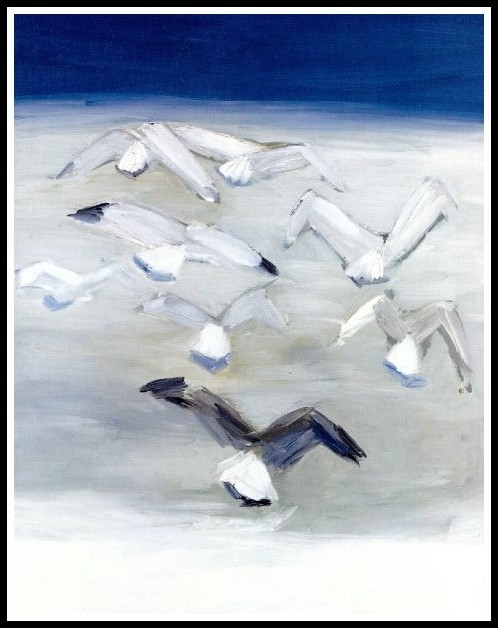

Nicolas de Staël, Mouettes, 1955

Furthermore, many of the passages dealing with Ninon’s disease are set indoors and in places generating claustrophobia (e.g. a waiting room, the hospital lift, her final confinement to bed). The closer we move towards the wedding, however, the more outdoor spaces we find: Ninon and Gino selling clothes at a market (p. 102) or rowing to an island in the river Po (p. 91 ff.), Gino’s father Federico walking through a heap of scrap metal (p. 59f), or Zdena on an open boat, Tsobanakos, too, is constantly outdoors: selling tamata in the market, standing outside a friend’s bar, sleeping on a terrace (p. 136), or waiting on a platform at the Piraeus train station. Jean’s motorbike ride through Italy is a form of open-air travel, and for Berger himself riding a motorbike symbolizes an act of liberation that ‘bestows a sense of freedom’: ‘After a few hours of driving across the countryside, you feel you have left behind more than the towns and villages you’ve been through. You’ve left behind certain familiar constraints. You feel less terrestrial than when you set out.’1 It bears symbolic significance when, during their first sexual intercourse, Ninon and Gino break the walls of a shack and suddenly find themselves in an open field, underneath an apple tree—love sets free, quite literally. Finally, the wedding is the culmination point of this movement into the open. Everything takes place in ‘an open-air basement and the ceiling is the sky’. The band plays on an open-air stage, people dance on makeshift floorboards laid out on the grass, and the guests are seated in a field underneath—again—three apple trees. The feast of love comes to stand for an act of liberation, a celebration of the present moment that lets one forget Ninon’s disease.

1 – John Berger, ‘How Fast Does It Go?’ In: Keeping a Rendezvous (London: Granta, 1993) p. 195 ff.

Nicolas de Staël, La route d’Uzès, 1954

This liberating spirit can even be traced to the semantics of the novel. Both Zdena and her travelling companion Tomas fail in their attempt to bring words into an encyclopaedic order. Zdena’s Dictionary of Political Terms and Their Usage, 1947 Till Today has not made any progress in the four years after the end of communism; on the boat to the wedding she is still collecting entries for the letter ‘K’. Tomas’ Encyklopédia Slovenska runs out of money, forcing him to earn his money as a taxi driver. Opposed to these failed encyclopaedic enterprises is the attempt of Ninon’s friend Marella to rename the infection. She no longer speaks of AIDS but calls Ninon’s disease ‘STELLA’. Unlike Zdena and Tomas, she does not seek to establish the significance of a word or fix a meaning to it. On the contrary, her invention, too, is an act of liberation. By renaming the disease she frees it from its usual connotations (prostitution, homosexuality, drug-addiction, criminality) and gives Ninon and herself space to redefine what the disease means in her particular case. For them, Ninon’s disease does not necessarily have to be what AIDS means to most; giving it their own secret name, they can reach a personal definition. Thus, the gesture of liberation is mirrored in the creation of a single word.

Nicolas de Staël, Nu assis, 1953-54

Berger’s auditory style gains significance before the background of this general theme of liberation. A myth frequently alluded to provides the crucial link: that of Orpheus. Orpheus, son of a Muse and Apollo, was gifted with supernatural musical skills, as is well known. His singing was so beautiful that animals and even trees and rocks moved around him in dance. When his wife Eurydice died of a snakebite, he ventured to the edge of the Underworld, and his beautiful voice so moved the guardians Charon and Cerberus that they let him pass. Even Hades, god of the Underworld, was moved by Orpheus’ song and allowed him to take Eurydice back into the world of the living. He set one condition, however: on their way out they were not allowed to look back. When Orpheus perceived the light of the world of the living, though, he turned around to share his delight with Eurydice. In that instant she disappeared forever.

Nicolas de Staël, Nu couché, 1953

Although in To the Wedding this myth is never established as a proper narrative thread, the attentive reader will find allusions to it throughout the novel. Once, the Greek singer is mentioned explicitly: ‘The signalman’s road goes through a copse of willows. The tree from which Orpheus took a sprig when he went to find Eurydice: the tree whose bark contains salicin, which works as a pain-killer like aspirin’ (p. 82). The willow tree is a recurring motif (pp. 44, 52) and appears most prominently when Gino brings Ninon in a thin barque to an island in the river Po. There she grasps a willow branch and some grass, ‘Gino’s grass’ (p. 95). The whole scene has a dreamlike quality and reminds one of Orpheus soothing Charon, crossing the Styx, and offering Eurydice the sprig of the willow tree. The event is highly symbolic: by crossing the mighty river in a small, gondola-like boat, Gino intends to show Ninon ‘how we’re going to live, you and I’ (p. 95). In other words, he intends to defy Ninon’s disease with his love as he defies the river’s power with his narrow boat. He imagines them living as if on an island, isolated from all those who have prejudices about AIDS, Yet, he is willing to take the risk and to dare the crossing, just as Orpheus dared to cross the Styx.

Nicolas de Staël, Les cyprès, 1953

It seems as though the narrator wanted to help Gino in his difficult task of bringing Ninon, who had already given up hope for herself, back into the realm of the living. His narration gradually turns into music—into Orpheus’ song. Tellingly, music is repeatedly alluded to. Tsobanakos’ friend Yanni plays the bouzouki, a traditional Greek string instrument resembling a mandolin, and pieces of music are frequently mentioned: a Greek rembetiko (p. 10), a nocturne for piano (p. 13), a song by The Doors [‘Strange Days’] (p. 24), a soldiers’ tune (p. 28), the French chanson ‘Quel joli nom de Ninon’ (p. 33) and a song titled ‘Last Friday Drives Monday Crazy’ played at the wedding (p. 198).

STRANGE DAYS

The Doors

Strange days have found us

Strange days have tracked us down

They’re going to destroy

Our casual joys

We shall go on playing or find a new town

Yeah!

Strange eyes fill strange rooms

Voices will signal their tired end

The hostess is grinning

Her guests sleep from sinning

Hear me talk of sin

And you know this is it

Yeah!

Strange days have found us

And through their strange hours

We linger alone

Bodies confused

Memories misused

As we run from the day

To a strange night of stone

Nicolas de Staël, Marseille, 1954

In fact, the novel opens with a song by the ancient poet Sikelidas [Asclepiades of Samos]:

Wonderful a fistful of snow in the mouths

of men suffering summer heat

Wonderful the spring winds

for mariners who long to set sail

And more wonderful still the single sheet

over two lovers on a bed.

And time and again we witness how Tsobanakos’ narration itself turns into verbal music, as for instance in the account of the wedding dance.

The beat enters Ninon’s bloodstream defying the number of lymphocytes, NKs, Beta 2s. Music in my knees for Gino, her body says, music under my shoulder blades, across my pelvis, between each of my white teeth, up my arse, in my holes, in the curly black parsley on my crotch, under my arms, down my oesophagus, everywhere in my lungs, in my bowel which goes down and my bowel which comes up, there is music for Gino, music in the little bones of my fingers, in my pancreas and in my virus which will kill, in all we fucking can’t do, and in the unanswerable questions my eyes ask, there is music playing with yours, Gino. (p. 194)

Nicolas de Staël, Le Lavandou, 1952

The breathtaking speed of this sequence, the pulsing rhythm, and the hypnotizing parallelism all help to endow the prose with a musical quality. The recurring key-word ‘music’ marks the rhythm of the sentences like the beating of a drum—or the beating of a heart. For with the music we enter Ninon’s body:

It is strange how the place, where music comes from, changes. Sometimes it enters the body. It no longer comes in through the ears. It takes up residence there. When two bodies dance, this can happen swiftly. What is being played is then heard by the dancers as if it were a recording, a millionth of a second late, of the music already beating in their bodies. (p. 193 f.)

It is as though the flow of verbal music was equated with the flow of Ninon’s blood; the musical stream of words mirrors that of her blood, and the rhythm of the sentences corresponds to that of her beating heart. Even the fatal virus in her blood finds its verbal equation in the toneless, almost inhuman ugliness of the abbreviations that denote it. Acronyms such as ‘NKs’, ‘Beta 2s’, or earlier ‘HIV’ (p. 75), ‘SIDA’ (p. 78), ‘AZT’ (p. 115), ‘T4’ (p.87), or ‘CD4’ (p. 119) are as much alien elements in the flow of words as the virus is an alien element in the young blood of Ninon. As the rhythm of the sentences becomes the beating of her heart, however, the narration must not stop. Its force, its driving pulse conjures up Ninon’s liveliness, hence the omission of punctuation marks other than commas. Full stops, semicolons, or exclamation marks are all omitted in order not to let a single moment of silence slip into the narration, in order to avoid the flow of words coming to a pause. Music—and with it the music of language—becomes an antidote to an incurable disease by stressing the present moment and making one forget the future and the threat of impending death.

Nicolas de Staël, Martigues, 1954

Thus, Tsobanakos’ narration turns into a gesture: it is meant to soothe the psychological pain of AIDS, In a broader context, To the Wedding takes up the topos of literature as an antidote to death. Shakespeare immortalized his ‘dark lady’ in the sonnets and concluded ‘As long as man can breathe and eyes can see, / so long lives this and this gives life to thee’, implying that every reader will, in the act of reading the sonnet, lend his breath to the figure of the ‘dark lady’, thus making her come to life again. Similarly, each time someone reads To the Wedding, Ninon comes back to life—even though only in the mind of the reader. If music is the temporary remedy for AIDS, literature is the antidote to oblivion, and we witness the resurrection of Ninon the AIDS-victim through the text. The chronological setting of the novel is telling in this regard: the story begins on an Easter Sunday and culminates in the wedding that takes place on June 8th (p. 111). In other words, it covers the span of time between Christ’s resurrection and Pentecost—the time of Christ’s corporeal death (an event explicitly ‘part of the story’, p. 103) and the descent of the Holy Spirit onto the disciples. On a more worldly, profane level, the story of Ninon is nothing else: the transformation of her mortal body into an apparition of the mind—a literary character.

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel de Vaucluse, 1953

Thus, the stress is on the performative aspects of literature. It is as if Tsobanakos believed that saying things could make them happen. And indeed, the entire narration is, as we have seen when we discussed its unclear ontological status, intended as an alternative to Ninon’s real life, the life in which the wedding ‘didn’t take place’. Tsobanakos seems to tell her: ‘Do not be sad Ninon, I will tell the story of your wedding, and in my story it will happen.’ Hence the visionary future tense in the account of the wedding feast itself: it has not yet taken place, but as Tsobanakos narrates the wedding with its curious children, the mythical meal, and the ecstatic dancing comes alive before our inner eyes and ears. The sound of a word is in this auditory style more than just a means of a signifying act; it calls into existence an imaginary world that can seem to the reader as real as the factual world.

Nicolas de Staël, Ciel de Vaucluse, 1953

Telling is making things happen—this seems to be the essence of literature, not only for Tsobanakos, the narrator, but also for Berger, the author. In a short essay he describes a revealing dream:

I once had a dream. In the dreamt country a decree had been passed which was binding and which everybody accepted: according to this decree, every word, either spoken or thought, had to be cashed for what it signified. It was as if the language and its economy had returned to the gold standard, so that every coin or bill was exchangeable for its equivalent in gold. If you thought ‘tree’ in that country, the tree had to appear and be there. In thinking ‘tree’, tree became present. In thinking ‘morning’, morning was. The words, according to this new decree, could not be left free-standing: they were porters of what they signified. All this applied not only to nouns, but also to verbs, adverbs, etc. When you thought ‘dig’, the act of digging was enacted. If you added the adverb ‘sadly’, sadness came and was as unmistakable as salt on the lips.1

1 – John Berger, ‘Lost off Cape Wrath’. In: Keeping a Rendezvous, p. 213f. See also John Berger, And Our Faces, My Heart, Brief as Photos (London: Granta, 1992) p.14: ‘What distinguishes this state [between waking and sleeping] from that of full wakefulness is that there is no distance between word and meaning. It is the place of original naming.’

Nicolas de Staël, Composition, 1951

Berger’s prose aspires to this sensuous quality of words. Needless to say, this ‘word-spinner’s utopian dream’ cannot come true.1 Yet, by stressing the creative process of reading with the help of an auditory style that makes the narration appear as if it was instantaneously told by Tsobanakos, the novel does call Ninon, Gino, Jean, Zdena, and Federico into existence. Berger adds: ‘The country in my dream was, in fact, literature.’2 It seems that his writing is a continuous exploration of this country. Berger is not satisfied with merely telling a story; for him, literature enacts what is being said, it cashes the sound of a word for its meaning; for him, literature is making the words come true in the reader’s imagination. The circle closes, for this defiance of mere delectatio, the passive consumption of books for one’s own pleasure, springs from his ‘rational and humane Marxist convictions’.3

1 – Berger, ‘Lost off Cape Wrath’, p. 214

2 – Berger, ‘Lost off Cape Wrath’, p. 216

3 – ‘John Berger’, Contemporary Novelists, ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer (USA: St. James Press, 2001)

Nicolas de Staël, Les muriers, 1953

Only if Berger believes in the power of words to change the real world through changing the world of our imagination does a literary social engagement make sense. Literature turns into a gesture, and indeed, To the Wedding ultimately attempts to be more than merely a story: ‘The tama of a heart in tin was not sufficient. I was troubled from the moment the signalman said “Everywhere” and I knew—or I thought I knew—what it meant. Another tama was needed, made this time not in tin but with voices. Here it is. Place it by the candle when you pray…’ (p. 202). The novel itself turns into a tama, a magic object with healing powers. It is its auditory style, though, that turns To the Wedding into a gesture. It stresses the fact that the novel is not to be regarded as a self-contained work of art but rather as a script to be read aloud or in the imagination. This speaks of a performative concept of literature. Berger’s almost audible prose ultimately does to us what the oblivious wedding dance and the ecstatic surrendering to the power of music do to the lovers: it creates an immediacy that sharpens our senses for the present moment, drowning the future and thus defying death.

Nicolas de Staël, Paysage, 1954

RALF HERTEL: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2024 | All rights reserved

Comments