I. INTRODUCTION | II. HEDDA GABLER: POSTMODERNISM VS. NATURALISM – A CRITIQUE OF FOUR PRODUCTIONS (1980-2016)

HEDDA GABLER, IBSEN’S GLORIOUS CREATURE

PART II – HEDDA GABLER: POSTMODERNISM VS. NATURALISM – FOUR PRODUCTIONS (1980-2016)

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

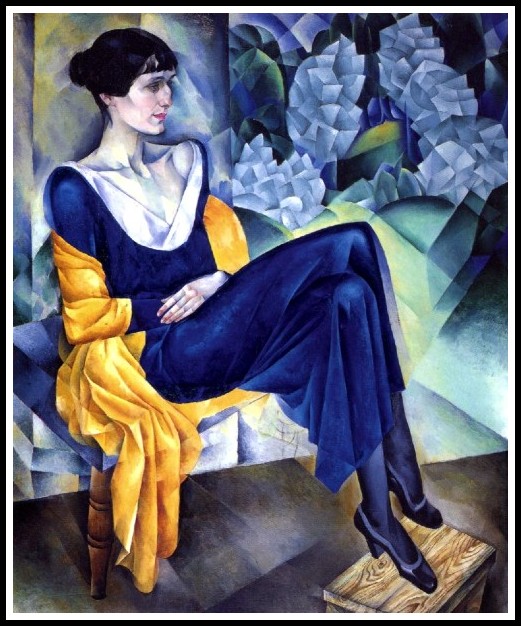

Nathan Altman, Portrait of Anna Akhmatova, 1915

I. INTRODUCTION

Numerous productions of Hedda Gabler fail to deliver the excitement Hedda’s capacity to fascinate1 deserves. Why? This is the question this essay, the second in a series of five posts, will address. In doing so it will examine the play’s mise-en scène, focusing on the challenge of staging a classic work today. I will demonstrate, in posts 4 and 5, how the Norwegian National Ballet’s production of Hedda Gabler rises above all the rest, delivering a Hedda who unfailingly fascinates and in doing so, renders all the richness of Ibsen’s drama. In this essay and the following one, I will examine eight productions, four in each post, that are currently available via streaming and/or DVD. The eight selections are given below, listed by director, company, actress playing Hedda, year of production, and availability:

HEDDA GABLER POST 2

1 – Ivo van Hove | National Theatre (London) | Ruth Wilson | 2016 | streaming: NT at Home

2 – Thomas Ostermeier | Schaubühne (Berlin) | Katharina Schüttler | 2005 | youtube (in German)

3 – Roman Polanski | Théâtre Marigny (Paris) | Emmanuelle Saignier | 2003 | DVD (in French)

4 – Thomas Langhoff | Fernsehens der DDR (GDR TV) | Jutta Hoffmann | 1980 | DVD (in German)

HEDDA GABLER POST 3

5 – Trevor Nunn | Royal Shakespeare Company (London) | Glenda Jackson | 1975 | youtube

6 – Waris Hussein | BBC | Janet Suzman | 1972 | youtube

7 – Raymond Rouleau | France Télévision | Delphine Seyrig | 1967 | Amazon Prime (in French)

8 – Alex Segal | Paramount-BBC-CBS | Ingrid Bergman | 1963 | youtube

1 – See Part 1, Hedda Gabler: Psychosexual Dynamics

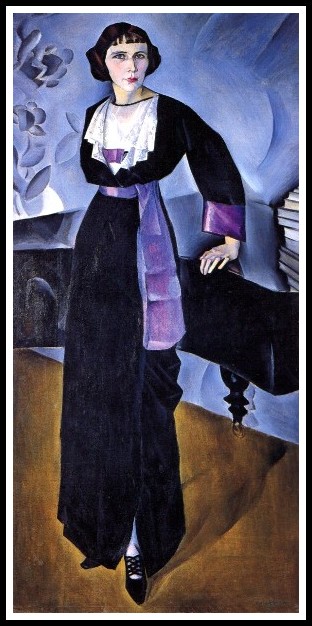

Nathan Altman, Lady at the Piano, 1913

My thesis can be stated simply: It is because many productions of Hedda Gabler focus on the text of the play rather than its subtext that they fail to deliver the excitement Hedda’s capacity to fascinate deserves. In Part 1, Hedda Gabler: Femininity & Psychosexual Dynamics, I argued that ‘Hedda fascinates because Ibsen situates her in the very middle of the primal scene of fascination: the difference between the sexes’ and that ‘if Hedda continues to fascinate us, it is because, just like her, we too are obsessed with sexual difference’. That is the subtext of the play—Hedda’s struggle to come to terms with her femininity and sexuality—and most directors of Hedda Gabler, in failing to use it effectively, ‘fail to deliver the excitement Hedda’s capacity to fascinate deserves’. Excitement, in the spectator’s experience of a play, means ‘a heightened sense of being’: one exits the theatre a different person from the one that entered it. My thesis can now be restated even more simply: In many productions of Hedda Gabler the spectator exits the theatre no different from when he entered it, and this is so because the director did not take sufficient account of the play’s subtext. How does this failure, this inadequate—or even absent—integration of the subtext into the mise-en-scène, manifest itself in the eight productions under consideration? In a bid to understand how the directors’ choices resulted in a failure to achieve the objective of theatrical art—to produce a ‘heightened sense of being’—let us now examine each of the eight productions (four in this essay, four in the following one).

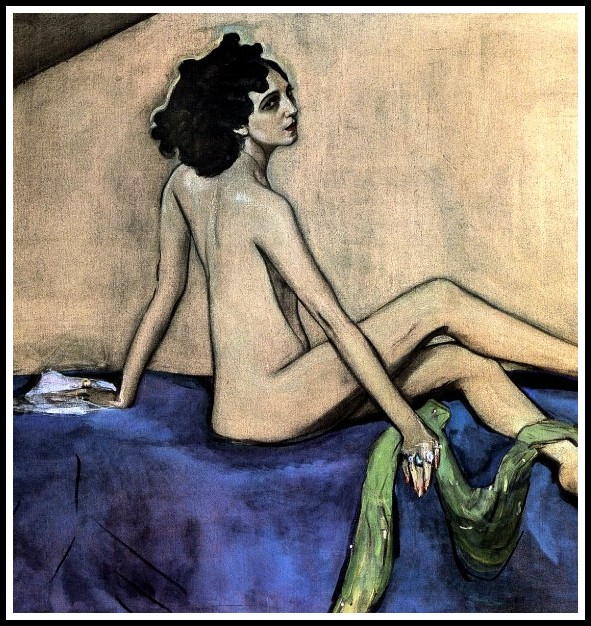

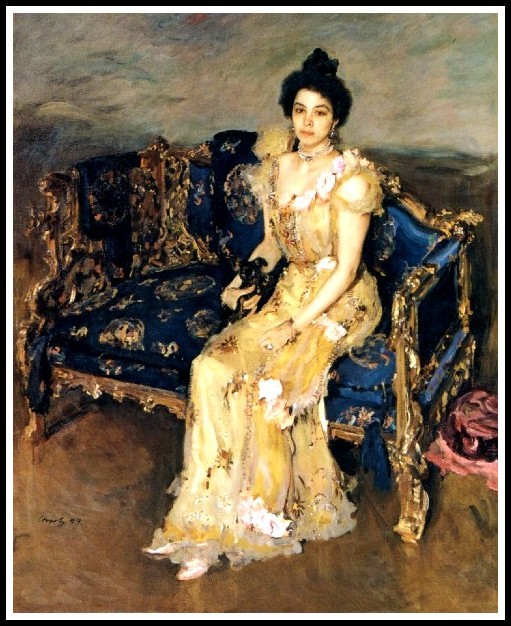

Valentin Serov, Ida Rubinstein, 1910

II-A. HEDDA GABLER: IVO VAN HOVE | NATIONAL THEATRE | 2016

The set is eye-catching: a huge open space, a piano, vases of flowers, a couple of chairs, a sofa/bed; unfinished walls housing a cabinet, Hedda’s gun case, and an intercom screen; sliding glass doors with variable light, hinting at an outside. The actors, unlike in most earlier productions, are the right age for their parts: refreshingly young. They eat steamed noodles, speak a contemporary idiom, and dress in casual elegance; their gestures are familiar, their interrelations easily recognized. The audience chuckles regularly as everything comes together to make—a banal sitcom. Completely deaf to the beating heart of Ibsen’s play—Hedda’s psychosexual dynamics—this version, failing to effectively put forth its alternative reading of the drama, falls flat. Why?

Alexander Roslin, Zoie Ghika, Moldavian Princess, 1777

Ivo van Hove has clearly articulated his ‘alternative reading of the drama’: ‘Hedda Gabler today is about giving audiences a sign of our times, of the emotional emptiness that we have to deal with; of not really being able to make a change, even when we want it, even when we have every possibility to do exactly that. Sometimes there is an inhibition in ourselves and we don’t know why. Hedda Gabler is really a suicide play. I think the suicide, the self-destruction, is deep inside Hedda long before the play starts. It’s not because of her marriage with Tesman that she commits this horrible, inescapable deed. It’s deep inside her, this urge to destroy, and when there’s nothing to destroy any more, she destroys herself.’1 If the clarity of this interpretation is exemplary, the reason it was not realized is equally clear: the director failed to find, through the actors, an organic form to ‘materialize’ his vision. And yet, again, we have evidence that he made every effort to do just that. Ruth Wilson (Hedda): ‘Ivo deconstructs the play like no one I know. Any preconceptions you have about how you might play the part or how it might be perceived are not what he does. So you have to come with a very open mind. You have to be flexible and fluid to what he’s asking of you. But what he does do, by deconstructing it in that way, is that he draws even more clarity about what the play is saying, what it’s about.’2 The actors, then, were not left to their own devices, but were explicitly directed. So what went wrong? Why does this interpretation of Hedda Gabler fall flat?

1 – British Theatre | 2 – Théâtre contemporain

Valentin Serov, Henriette Girshman, 1907

The fundamental reason, I contend, is the ‘postmodern realism’ of the production. Postmodern readings of the classics now being the norm, it is incumbent upon any production with artistic ambition to disrupt the audience ‘singing along with its own expectations’: to serve Ibsen, the play must draw the audience out of its comfort zone. As realism is the default aesthetic of mainstream theatre, my argument turns on the fact that today it encompasses not only the conservative form of sitcoms, but also postmodern challenges to conservative forms. Indeed, to an audience awash in a consumerism that can assimilate all rebellion1, this production of Hedda Gabler comes across as ‘realistic’. Indeed, that Hedda spends a day-and-a-half in her silk nightdress, barefoot throughout except when, to receive Brack, she slips on a pair of heels, strikes one as unremarkable. After all, if slouching comfy on a couch is a spectacle consumers can readily see themselves in, flattering the audience with the familiar, free of any subversion, is the commercial norm. Similarly, that Hedda playfully threatens Brack with a handgun (no longer her father’s dueling pistol, no longer a prop in her psychosexual universe) partakes of the harmless glamour of violence that is a staple of all entertainment. That she concludes the play by putting a bullet in her brain is simply a natural act for a super bitch and action babe who, thanks to Quentin Tarantino and Luc Besson, holds no mystery for the audience. And what happens every time snide Hedda snaps at Tesman? The audience, in an eerie echo of sitcoms’ canned laughter, chuckles. As for the set, its minimalist cool does indeed turn on the spectator’s ‘space cadet glow’: the problem is, in defiance of Ibsen’s intentions, nothing comes to darken it. For these reasons, then, this production of Hedda Gabler falls flat: it is all too conventional in its unconventionality, all too passé in its postmodernism—it cannot ‘wake the spectator to wonder’.

1 – For an analysis of this phenomenon that draws on the theory of Jean Baudrillard, see my essay on Alexander McQueen’s fashion show, The Horn of Plenty.

Charles Carolus-Duran, Nadezhda Polovstova, 1876

Ivo van Hove chose to stage Hedda Gabler in a way that would make it relevant to contemporary society: ‘I always feel as a director an obligation to talk about people, themes that matter today, not things that mattered in the past. With Hedda Gabler, I don’t think Ibsen dealt with any important theme but more with a condition of human beings and society.’1 Emotional emptiness, spiritual paralysis, urge to destroy, self-destruction: this is what the director’s mise-en-scène was meant to convey. However, by ignoring the subtext of the play—Hedda’s struggle to come to terms with her femininity and sexuality—and focusing instead on his own interpretation—‘a condition of human beings and society’—he turns the play into a banality. Ibsen’s drama of Hedda’s struggle with herself is as relevant today as it was a hundred years ago and as it will be a hundred years hence: the rest is at one remove from what makes Hedda tick. The director’s sitcom mise-en-scène results in an ensemble piece of social anthropology undermined by its refusal to take itself seriously—very postmodern! Finding herself stranded in an episode of ‘Friends’, stripped of her ability to fascinate and excite, Hedda becomes a neutered cartoon character instead of Ibsen’s glorious creature. Yes, we perceive her boredom and paralysis, but we also perceive her as boring and unstriving—which is not how Ibsen conceived her. Yes, she appears emotionally sterile, but where, we wonder, are the ‘moments of true feeling’ Ibsen accorded her? And yes, the hurling of the flowers signifies her howl of frustration, but her suicide comes across as gratuitous because her demons were never given their due. And thus the tragedy of Hedda’s struggle with herself gives way to the melodrama of her struggle with others. In an effort to make Hedda Gabler relevant today, Ivo van Hove sacrifices the singularity of the individual—the foundation of all art—to the banality of the social. In this, as we shall see, he is not the only director so misguided.

1 – British Theatre

Valentin Serov, Sophia Botkina, 1899

Van Hove was aware of this danger, and to ward it off he accorded Hedda four ‘soliloquies’, four attempts to give us access to her interiority. These take the form of musical interludes, with ‘Blue’, the Joni Mitchell song, providing the music. (A purely instrumental piece would have worked better: when a director has recourse to ‘illustrative’ music, he’s confessing his lack of confidence in his own mise-en-scène: ‘If I can’t show, I will tell’.) In the first interlude, Hedda stands by the window and roughs up the Venetian blind: she’s feeling oppressed, frustrated, confined. In the second, a riot of petals scatters across the floor as she beats a bouquet to smithereens. From each vase she then grabs the flowers and flings them into the void behind her. That done, with quiet deliberation she goes round the room, fixing flowers to the wall with a staple gun: after the bootless rage, an attempt at self-soothing. In the third interlude, Berte and Hedda have a smoke; Hedda’s strained breathing betrays her dark feelings. In the final interlude Hedda, seated on the piano, does a cacophonic hop across the keys: the wild dance tune that heralds her death. As Hedda ‘soliloquies’ these interludes do indeed succeed (though the quadruple playing of ‘Blue’ is overkill from underconfidence). On the whole, however, van Hove’s ‘postmodern realism’ drains Hedda of her interior drama: the creature of fascination and excitement the subtext of the play would have her be is nowhere to be seen. Pity.

Konstantin Somov, Lady in Blue, 1900 (detail)

II-B. HEDDA GABLER: THOMAS OSTERMEIER | SCHAUBÜHNE (BERLIN) – ZDF | 2006

Thomas Ostermeier’s adaptation of his stage version of Hedda Gabler for Germany’s Channel 2 is outstanding. Nevertheless, it, too, fails to render the fascination and excitement inherent in Hedda as Ibsen conceived her. Why? This is the question I will address here. In doing so, I recognize that the fineness of Ostermeier’s artistic sensibility, theatrical vision and directorial approach requires a corresponding acuity on my part: a challenge I will endeavour to meet. This, in turn, will oblige me to quote extensively from Ostermeier’s own enunciations of his theatrical credo as he presented it in the following documents: ‘Theatre in the Age of Its Acceleration’, a talk given in 1999; ‘Insights into the Reality of Human Community: A Defence of Realism in Theatre’, a talk given in 2009; and ‘Reading and Staging Ibsen’, an article published in Ibsen Studies in 2010.1 I will also draw on an interview the director gave Inferno magazine in 2012 (here, I translate his French into English). So, why did Ostermeier fail to render Hedda’s individuality? Why did his striking production fail to articulate what makes Hedda tick? Why, in short, did ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’, at home in her glass house, become invisible?

1 – All these documents are published in Peter Boenisch & Thomas Ostermeier, The Theatre of Thomas Ostermeier (London: Routledge, 2016)

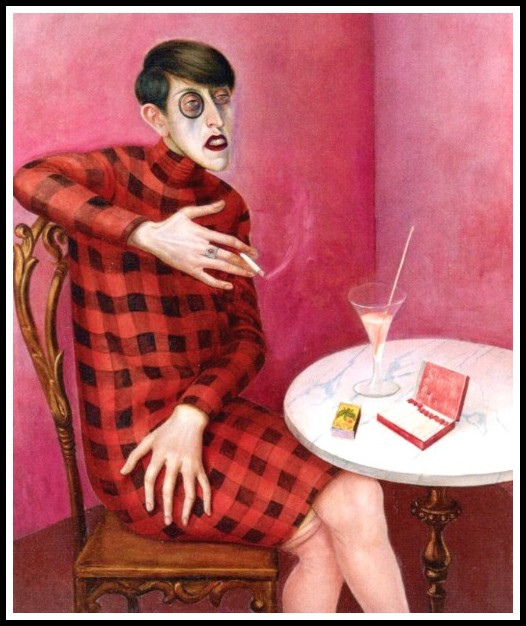

Otto Dix, The Journalist Sylvia von Harden, 1926

The fundamental reason, I affirm, is simply that Ostermeier is more interested in the play’s socio-economic and cultural dynamics than in its psychosexual ones: he is more interested in Hedda Tesman than in Hedda Gabler. Readers familiar with his conception of the play will disagree. The proof of the pudding, however, is in the eating: it is on the basis of the stage/video performance, not the director’s intentions, that I maintain my thesis. Before examining that performance, let’s consider Ostermeier’s conception of the play. In his Ibsen Studies article, he writes:

‘The conflict of Hedda Gabler is actually quite difficult to describe, yet even if we cannot describe it easily, everybody can recognise Hedda’s feelings: living the wrong life, being together with the wrong person, not being courageous enough to live an independent life, hating the others around her because they show her, like a mirror, how miserable and small her courage and ideals are.’

‘In Ibsen’s plays, the characters are completely preoccupied with constant worries about financial or economic issues. This unwavering belief in the power of money destroys every human relationship. In Hedda Gabler, Tesman’s career as a professor is put in danger by Løvborg—he cannot afford the house he bought if he doesn’t get the job. Career, social status, money, status symbols—again, the house in Hedda Gabler—are more important than the human beings around them, more important than emotional relationships, more important than love and friendship. The characters have thus sacrificed their souls, their emotions, their passions, their love or their ability to love to their financial desire. They are living in a rationalised, secularised, cold world where some of them still try to maintain other values, but then suffer total shipwrecks in this world. What is interesting to me as a director is to have a playwright who shows how human beings, with all their emotions, try to survive with their souls intact in a completely materialistic and rationalised world, where only the power of money rules.’

Here, we clearly see how Ostermeier is attuned to Hedda’s feelings, but subsumes them in his socio-political understanding of contemporary Western society. His analysis may be perfectly accurate, but to use Hedda Gabler as a vehicle to illustrate it is to foreclose to us what makes her interesting: her individuality.

Otto Dix, Portrait of Mrs. Martha Dix, 1928

In his 2009 talk, Ostermeier says:

‘One may suggest that realism necessarily means political theatre, yet realist theatre should perfect its ability to portray insights into the reality of human relations. A realist notion of theatre is based on the assumption that the conduct and behaviour of people with each other changes in accordance with societal transformations. For instance, today Hedda Gabler’s boredom would present itself differently from the way it did in the late-nineteenth century, in terms of its articulation, its forms, and Hedda’s interpersonal relations. It would express itself in a different tone, different forms of physicality, different movements and gestures. Besides identifying those differences, the ambition of this approach to making theatre is to observe the reality that surrounds us, the reality of human behaviour in all its ambiguity and contradictions, and to find forms to express it on stage.’

And in his 2012 Inferno interview, he declares:

‘Theatre enables us to tell stories from our own perspective so that we may understand in a fresh way the fundamental conflict: that between desire and reason. This conflict is the engine of all Ibsen’s plays. Hedda Gabler didn’t have the courage to marry Eilert Løvborg, she hates herself for having chosen Tesman and the comfortable life he can provide. The world reflects her own mediocrity.’

Again, we see that for Ostermeier, the personal and the political are inseparable. We also see that he is determined to give full expression to the ‘ambiguity and contradictions’ inherent in human behaviour: he is neither an ideologue nor, a fortiori, a dogmatist. Nevertheless, his obsession with situating Hedda socially does her a disservice: in playing up the melodrama taking place in society, he downplays the tragedy raging in Hedda’s psyche. ‘A legitimate directorial choice’, you might counter, to which I would reply, ‘What does Ibsen call his play—Hedda Gabler or Hedda Tesman?’

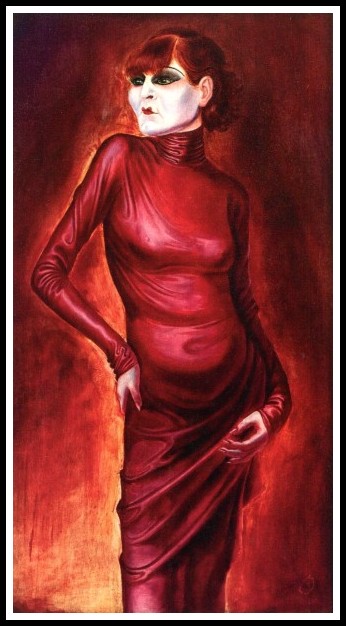

Otto Dix, The Dancer Anita Berber, 1925

From the perspective of Hedda Tesman, the conflict between reason and desire is perfectly understandable; indeed, both ‘feet’ of the conflict, so to speak, are firmly planted on the ground of ‘common sense’. From the perspective of Hedda Gabler, however, the conflict is more complex; in exceeding ‘common sense’ it finds itself on quicksand. Maintaining the tension between ‘common sense’ and ‘quicksand’, the Gabler stance encompasses more of Hedda’s experience. In short, the Tesman perspective cannot account for what the Gabler one recognizes: that when it comes to reason, ‘the ego is not master in its own house’ (Freud), and that when it comes to desire, ‘we are only alive because we desire, but in our desiring we are obscure to ourselves’ (Adam Phillips). Ostermeier’s mise-en-scène, despite the brilliance of its production, takes the Gabler out of Hedda.

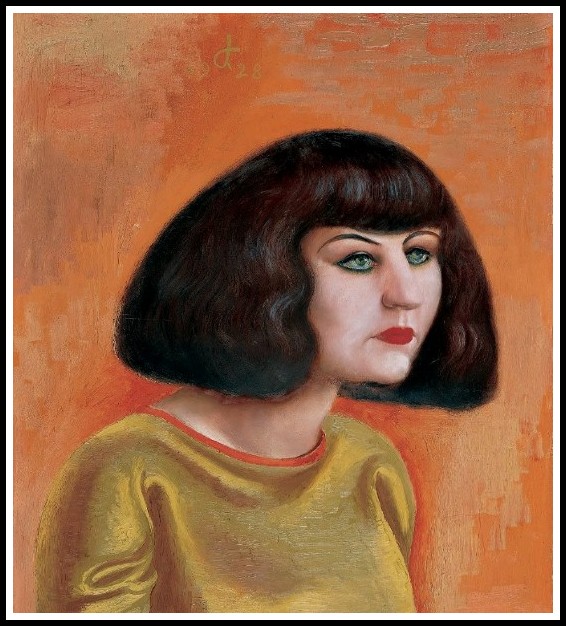

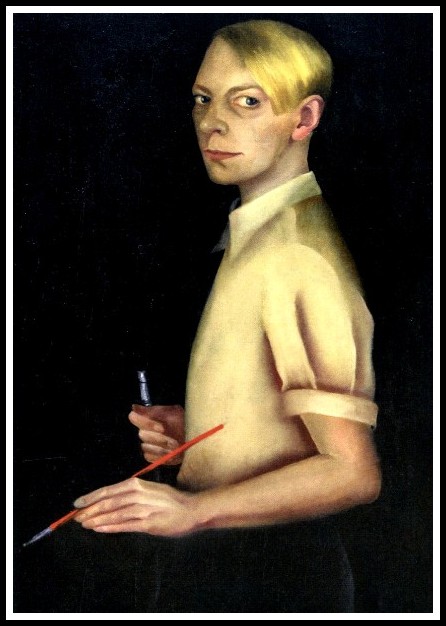

Kate Diehn-Bitt, Self-Portrait as an Artist, 1935

Just who, in fact, is Hedda Gabler? Who is Ibsen’s glorious creature? If she haunts the theatre, if she fascinates and excites and seems to exist beyond the stage, it is certainly not because, as a certain discourse contends, she’s a lightning rod for social tension, a victim of patriarchal oppression, or an upholder of beauty in an ugly society. Whatever truth may lie in these views, they cannot account for that heady blend of attraction and repulsion that is the essence of Hedda’s fascination. She’s a sublime bitch, we can all agree, but what else can we really say? Katharina Schüttler, the actress who plays Hedda in the Schaubühne production, offers this insight: ‘It is difficult to even understand what is going on with this woman. The question is actually what she really wants. It is very difficult to find out whether she really means things the way she says them. You can always put the questions to Hedda anew. That’s one of the reasons why I’ve been able to play Hedda for so long.’1 (Over the 15-year period from 2005 to 2020, Katharina Schüttler played Hedda Gabler 250 times.) You can always put the questions to Hedda anew: that, precisely, is why Hedda—like Carmen, like Hamlet, like Cathy of Wuthering Heights—endures: however finely-meshed our net of discursiveness, she escapes capture by whatever we may say about her. The only hope of getting a hold on Hedda without choking the life out of her is to find, by picking up the clues Ibsen gives us, a theatrical means to access her subconscious. Not, as in this production, by a horizontal extension that brings into the play the effects on the characters of contemporary society, but rather by a vertical extension into the depths of Hedda’s mind (see Hedda Gabler, Part 1).

1 – Interview in Zeit Online, 15 January 2020

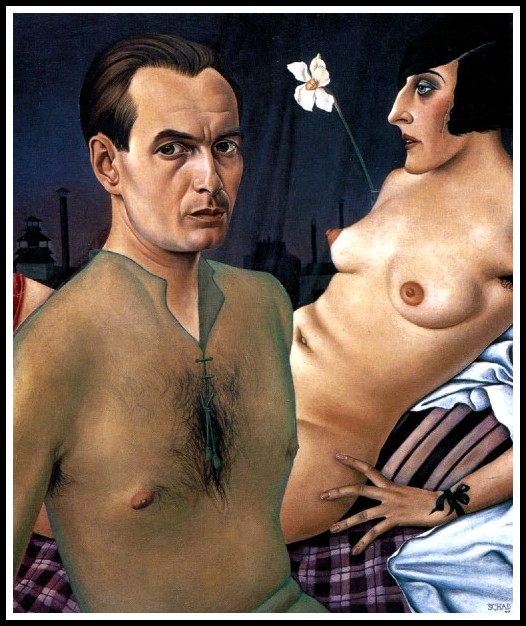

Christian Schad, Sonja, 1928

In his 2010 article, ‘Reading and Staging Ibsen’, Ostermeier writes:

‘In Germany, especially in the German Regietheater of the 1970s, 1980s and early 1990s, Ibsen was known as the playwright who revealed the mysteries of the soul. He was widely seen as the one who had put the ideas of Freud on stage before Freud himself had developed them. Consequently, the actor would try very hard to make us believe that his feelings on stage were sincere. Ibsen’s plays were performed with lots of pauses, emotional seizures, and passionate looks out of windows. Presenting Ibsen’s work in this way can be very boring, especially as this belief in feeling destroys the play and leads to performances in which the characters no longer act in the sense of taking action.’

The tradition of acting and mise-en-scène Ostermeier is referring to here belongs to a set of conventions that no longer convince even the least demanding spectator. If a director, striving to make manifest Hedda’s struggle with herself, chose to focus, say, on the hysterical component of her psychosexual dynamics, how could he or she do so without falling into the kind of caricature Ostermeier rightly denounces? They would have to find, with the actress, a theatrical form—movement, voice, gesture—that expresses it, one supple enough to be amenable to variation and subtle enough to avert the burlesque. One of Freud’s hysterical patients provided just such a theatrical form: “In severe hysterical attacks, she is simultaneously ‘woman’ and ‘man’: with one hand she holds her dress tightly against her body (as a woman) while with the other hand she is trying (as a man) to tear it off”.1 Far from conveying a caricatural ‘seizure’, a good actress could simply suggest this holding on/tearing off dynamic in a variety of ways. In doing so she would, in a kind of mise-en-abîme, stage Hedda’s struggle with herself while Hedda herself is being ‘staged’. This is what I mean by ‘vertical extension’ into the depths of Hedda’s mind, there where her psychosexual dynamics are at work. ‘Vertical extension’ individualizes Hedda; ‘horizontal extension’, by assimilating her into a group, ‘collectivizes’ her. Dead conventions are definitely boring: collectivities that dissolve individualities are no less deadening.

1 – Catherine Clément, citing Freud’s ‘The Relation of Hysterical Fantasies to Bisexuality’, quoted in Gail Finney, ‘Maternity and Hysteria: Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler’, in Gail Finney, ‘Women in Modern Drama: Freud, Feminism, and European Theater at the Turn of the Century (Cornell University Press, 1989) p. 159

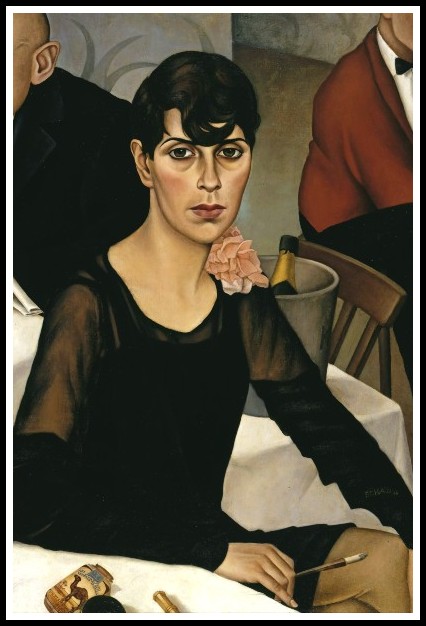

Ada Peldaviciute-Montvydiene, Nude with a Cigarette, 1934

Now let us see how all these considerations play out in Ostermeier’s production. His Hedda Gabler, though made for television, is highly cinematic. Steadicams and dollied cameras assure not only fluid motion but also dynamic angles. The set, bare but for a long sofa of Veronese green on a dark reflective floor, conjures a living room. Behind it, a wall of glass with sliding doors, now streaked with the melancholy rain of Hedda’s state of mind, now obscured by a fog through which her ghost from the past comes. At one end, perpendicular to the wall of glass, an opaque wall shields the ‘inner room’. The play’s conflicts are played out in a harmony of blues and greens, blacks, whites and greys. Vases of flowers, white lilies in transparent water, stand in for Fräulein Juliane Tesman and her promise of daily presence. Angled mirrors compose a partial ceiling: an evil eye in which the characters are reflected. Between the acts are interludes, and at the end there’s a coda: video scenes of blurry images—Hedda in the city, Hedda in the forest, Hedda shooting her guns; on the sound track, Brian Wilson baring his soul—an ironic comment, perhaps, on Hedda’s inability to bare hers. As for the action, the actors rarely avail themselves of the sofa: they’re mostly stand, hugging the walls, pacing the floor, with Hedda in her glass cage put to shame by Ted Hughes’ ‘jaguar hurrying enraged / through prison darkness after the drills of his eyes / on a short fierce fuse’. Yes, this Hedda could do with some wilderness in her eyes. (Speaking of glass cages, I recall a scene in Chinese Roulette where Fassbinder filmed his unfaithful couples as if they were in a display case. Fassbinder and Ostermeier: a certain affinity?)

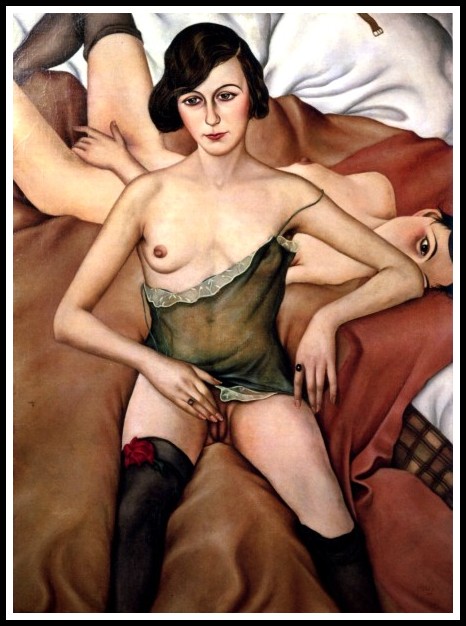

Christian Schad, Bettina, 1942

In his 2012 interview with Inferno Magazine, Ostermeier says:

‘Hedda Gabler is often played by older women, entailing the idea that her cruelty is linked to a decline in her sex appeal. My approach is different. I see Hedda more as a Sarah Kane character, with that kind of desperation. In fact, Katharina Schüttler played Cate in Sarah Kane’s Blasted. My adaptation of Hedda Gabler has a lot to do with Sarah Kane’s writing. In Katharina, there’s the femme enfant aspect but also the depressive side, which is not linked to age but rather to the mediocrity of her world and her cowardice.’

In Sarah Kane’s Blasted, three actors in a room and a few lighting and sound effects suffice to awaken the audience to the horror of human behaviour in a state of war and local tension. Given Ostermeier’s realist credo, it’s easy to see why Kane’s play appeals to him, but harder to see how it influenced his version of Hedda Gabler. Indeed, what he depicts in his interpretation is a state of both ennui and anomie, a state particular, perhaps, to a rich, self-satisfied society in the early 2000s. I very much doubt the director would mount the same production today. Regarding this question of timing and interpretation, Borges’ story, ‘Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote’, is instructive. In it, ‘Pierre Menard’ writes (around 1935) a few chapters of Don Quixote that are identical, word for word, to the original, but the effect of reading them is entirely different simply because the intervening centuries have furnished the reader with a different set of references and allusions, omissions and inclusions, from those that existed in Cervantes’ time. In staging a classic play today every director has to confront the ‘Pierre Menard’ phenomenon, and the choices they make—what to leave out, what to bring in; what to play up, what to play down—will determine their interpretation and mise-en-scène. For me, Ostermeier’s Hedda Gabler is first and foremost a portrait of a German generation—the chronically bored housewife, the eternal-student husband, the sharp and cynical lawyer, the golden-hearted aunt harking back to a simpler time, and the writer with a secret who can’t conform to convention. If Hedda is simply ‘depressed’, like untold millions of other people, because of ‘the mediocrity of her world and her cowardice’, is she still Hedda Gabler?

Christian Schad, Self-Portrait with Model, 1927

In Ostermeier’s framework—mediocrity, boredom, cowardice, depression—Hedda’s suicide is simply an act of self-hate. How does he stage it? He makes one key change from the way Ibsen outlined it. At the sound of the gunshot when Hedda shoots herself in the inner room, Jørgen, Thea and Brack, though suspended in a moment of surprise, maintain their positions. Jørgen says, ‘Oh, now she’s fiddling with those pistols again’; then, while Brack remains seated on the sofa, Jørgen and Thea continue sorting through Thea’s notes. Ostermeier then has Jørgen call out to his wife—Hedda? Hedda?—and remark, ‘She’s probably shot herself. That’s what I imagine’. Brack then delivers his line as Ibsen wrote it: ‘But God have mercy – people don’t actually do such things!’. Jørgen and Brack chuckle, Thea keeps sorting, then Jørgen resumes his note-shuffling. The camera partially circles the set (in the theatre version it’s the revolving stage that turns), revealing Hedda on the floor, back to the wall, leg splayed, blood dripping from her temple as well as from the wall. The Beach Boys’ plaintive ‘God Only Knows’, a refrain throughout the play, comes on again. Brack rises from the sofa, goes to the patio door; Jørgen and Thea join him there: three silhouettes now blurred in a video montage. This ending, in which the reality of Hedda’s suicide goes unrecognized, confirms my reading of Ostermeier’s mise-en-scène: he’s turned Hedda Gabler into a play about a generation’s indifference to the suffering of others. Hedda as victim is not what Ibsen had in mind.

Christian Schad, Deux filles, 1928

Just as Hamlet’s indecision is not simply a case of procrastination, so Hedda’s suicide is not just an act of self-hate: for both Hamlet and Hedda, there’s more to it than that. As I’ve tried to demonstrate, that ‘more’ cannot be found by ‘horizontal extension’—the indifference of a generation, its anomie and ennui—but only by a ‘vertical extension’ into Hedda’s mind. Ibsen, in his notes for Hedda Gabler, clearly suggested this,1 and the play as it stands provides sufficient clues to support this view. If Hedda Gabler still haunts the stage today, it is because of her presence, not her representativeness. To make her stand in for a milieu or a state of mind is to cut her down to our size. Hedda deserves better. A worthy production of Hedda Gabler is one in which the heroine’s capacity to fascinate and excite can flourish. Other productions may be excellent—even outstanding, as here with Ostermeier—but they are not worthy of ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’.

1 – See, for example, Elin Diamond, Unmasking Mimesis: Essays on Feminism and Theatre (Routledge, 1997) pp. 25-32

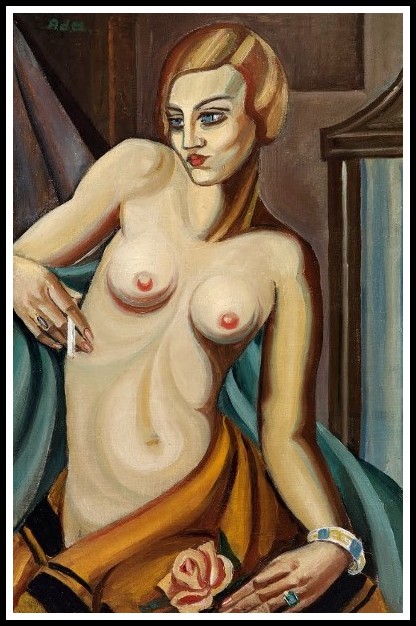

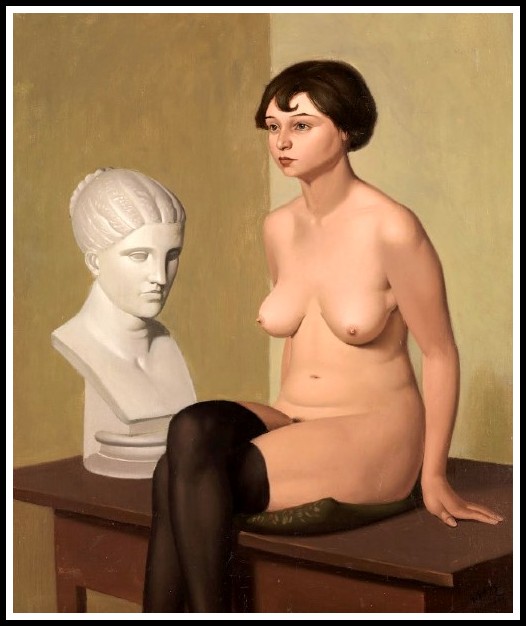

Georg Scholz, Female Nude and a Plaster Head, 1927

II-C. HEDDA GABLER: ROMAN POLANSKI | THÉÂTRE MARIGNY (PARIS) | 2003

This being a video recording of a stage play, it’s normal that Roman Polanski’s cinematic genius is nowhere in evidence. That his theatrical genius is equally absent, however, strikes one as an aberration. The director chose to stage Hedda Gabler as a nineteenth-century drawing-room drama. One expects something oblique in his approach—satire, comedy, a touch of the grotesque, or simply some good old violence and sex—but no, it is with a straight face that he delivers his period piece. Despite the ‘Pierre Menard’ phenomenon, he might just have been able to pull it off if one sensed he had a point of view on the play, something resembling an interpretation. Again, no—the journey from page to stage seems not to have stopped at the station of critical reflection. Most unlike Polanski. Furthermore, he whose direction is known to be punctilious seems to have left his actors to their own devices. So we have a Hedda who goes through the motions in her floor-length flounces, a Tesman who plays his lines for laughs, a slippery-sleek Brack stuck in a single register, a Thea and a Løvborg whose sincerity and dignity don’t mesh dramatically with the other characters’ attitudes, and an Aunt Juliane whose fit-to-type is simply too much. One emerges from the viewing resigned to one’s disappointment but irreconciled with one’s sadness—this is not the Polanski I know and love! And so, dear reader, let’s leave it at that: further discussion of this production would produce more heat than light, leaving the issues we are investigating in the dark.

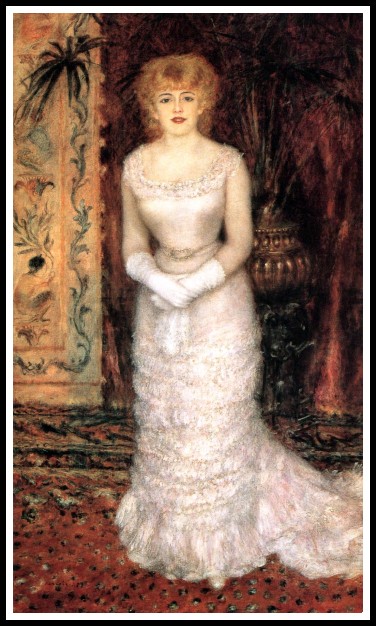

Renoir, The Actress Jeanne Samary, 1878

II-D. HEDDA GABLER: THOMAS LANGHOFF | FERNSEHENS DER DDR (BERLIN) | 1980

Of the eight productions of Hedda Gabler under consideration in this essay and the next, this one in many ways is the finest. It reinvigorates naturalist realism with such intelligence and finesse that it is not only convincing, but utterly compelling. What makes it so? After all, already in 1968 Martin Esslin was able to write:

“Naturalism, a movement which started out as a furious attack on the conventions of what was then regarded as ‘the well-made play’, as an iconoclastic, revolutionary onslaught against the establishment, has now turned into the embodiment of ‘squareness’, conservatism, and the contemporary concept of ‘the well-made play’. In the West End of London early Shaw and Ibsen have become safe after-dinner entertainment for the suburban business community—the equivalent of Scribe, Sardou and Dumas fils in their own day—the very authors whom Shaw and Ibsen had wanted to replace because they were safe and establishment-minded.”1

And in 1986, Alisa Solomon observed that:

“Prevalent American dramaturgy presents enormous obstacles for producers of Ibsen. Sitting through a naturalistic American play is like riding a commuter train for the zillionth time. Even when the people might seem curious or the scenery beautiful, the journey is tedious and predictable, and the destination rarely worth the trip. These plays, trundling through the same familiar terrain, have worn out the vehicle. As mainstream theatre and television have co-opted the simplest and least evocative aspects of naturalism, the genre has been belittled into exhaustion.”2

So how did Thomas Langhoff succeed in breathing new life into naturalism, a genre that, having become ‘the embodiment of conservatism’, has been ‘belittled into exhaustion’? This is the question I will address here.

1 – Martin Esslin, ‘Naturalism in Context’, The Drama Review: TDR, Vol. 13, No. 2 (Winter, 1968), p. 67

2 – Alisa Solomon, ‘Denaturalizing Ibsen/Denaturing Hedda: A Polemical Sketch in Three Parts’ in Before His Eyes: Essays in Honor of Stanley Kauffmann, ed. Bert Cardullo (University Press of America, 1986) pp. 85-86

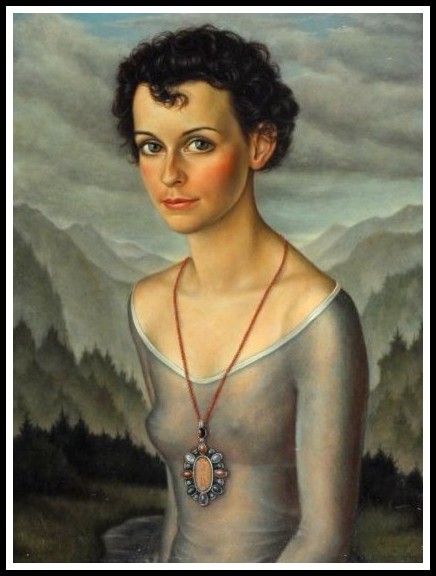

Ida Silfverberg Self-Portrait, 1868

Before doing so, however, I would like to offer a few remarks on alternatives to naturalism. They can be grouped into two main clusters. One consists in those plays that, in expressing their author’s vision, organically find their own voice and form. In this group I would include, for example, the plays of Beckett, Pinter, Jean Genet, Peter Weiss and Friedrich Dürrenmatt. Wedekind and Brecht would keep them company center-stage, Maeterlinck, Hofmannsthal and Yeats from the wings, and hovering in the air above, a host of contemporary contenders. These authors’ plays are inherently anti-naturalistic: no director would dream of staging them in any idiom but the playwright’s own. The other group consists of pre-modern plays—from the Greeks to Shakespeare to Ibsen, Strindberg and Chekhov—that the director feels free to stage in any aesthetic they like. Shakespeare and the Greeks seem to have a built-in dilettante repellent: to a large extent they resist corruption when they fall into incompetent hands. Not so for Ibsen, Strindberg and Chekhov: directors have no hesitation in adulterating their plays to suit their own conceptions. Here’s what Thomas Ostermeier had to say about this:

“Following the ultimate triumph of ‘directors’ theatre’ in the 1970s, the German theatre system began to revolve exclusively around itself, with productions citing, quoting, and cross-referencing each other. Detaching itself entirely from the world around it, it lost two layers of foundation from under its feet: firstly, the grounding in reality ‘out there’, and secondly, its own grounding. This affected the understanding—or rather, the utter misunderstanding—of its own role. Theatre became ever more marginalised in German society while its directing titans overestimated themselves on an ever grander, ever more deluded scale. They forgot that they had been employed to help the playwrights, to make their voices heard for a wider public, and not to stand between these two groups.”1

Ostermeier’s remarks, of course, are just as relevant to theatre scenes outside Germany.

1 – Thomas Ostermeier in Peter Boenisch & Thomas Ostermeier, The Theatre of Thomas Ostermeier (London: Routledge, 2016) p. 14

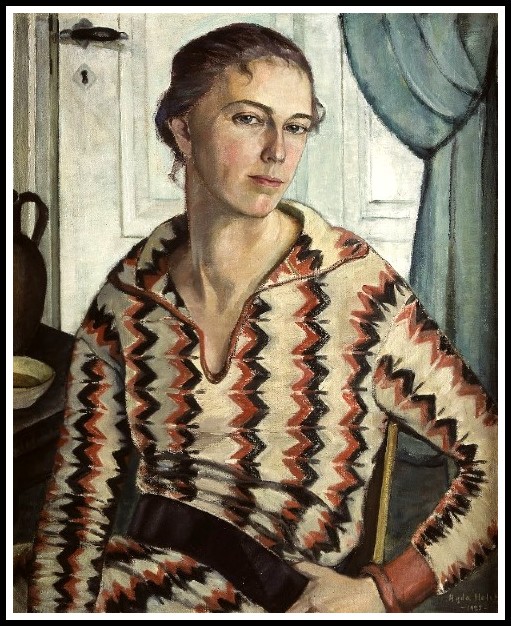

Agda Holst, Self-Portrait, 1925

These ‘ever more deluded’ directors and their ilk are generally free-riders on the bandwagon of ‘postmodernism’, that refuge for dilettantes of all stripes. They frequently have recourse to the ‘quotation marks’ and ‘ironic distance’ that Ostermeier denounces here:

‘I take the play seriously. What the characters say, what they do, is going to take place on stage. In my work, there are never those invisible quotation marks around the play, the characters, or the plot that one often finds in postmodern approaches to staging, especially of the classics. Irony is something the audience might feel as a result of watching a scene on stage; however, not taking the play seriously, adopting an ‘ironic distance’ from the start, is not my approach to creating theatre.’1

To ‘freshen up’ an old play by garlanding it with the gimmicks of postmodernism is to fashion a daring glass for the gullible.

1 – Thomas Ostermeier in Peter Boenisch & Thomas Ostermeier, The Theatre of Thomas Ostermeier (London: Routledge, 2016) p. 134

Elisabeth Jerichau Baumann, The Author Emma Kraft, 1850

What are the implications of all this for the staging of Hedda Gabler? Toril Moi’s analysis of ‘the postmodern problem with Hedda’ brings them out beautifully:

‘In recent years, Hedda Gabler has been one of Ibsen’s most frequently produced plays. In the United States, some of the most noticed productions have had great stars in the part of Hedda: over the years, I have managed to catch Annette Bening in Los Angeles, Kate Burton in New York, and Cate Blanchett in Brooklyn. Although Cate Blanchett is an uncommonly thoughtful actress, the Australian production of Hedda Gabler in which she starred was a mess. Blanchett’s Hedda was too witty, too exasperated, too impatient, and far too keen to fling her body around on every available sofa or chair. There was a lot of plumping of cushions and fidgeting with furniture. The pace was frenetic, to the point that Hedda’s burning of Løvborg’s manuscript became just another hectic event. At the end of the play, Hedda killed herself in full view of the audience. Predictably, the audience was neither moved nor shocked. While less frantic, the productions with Bening and Burton turned Hedda into a cynical, world-weary deliverer of caustic one-liners, more likely to kill her husband than herself.’

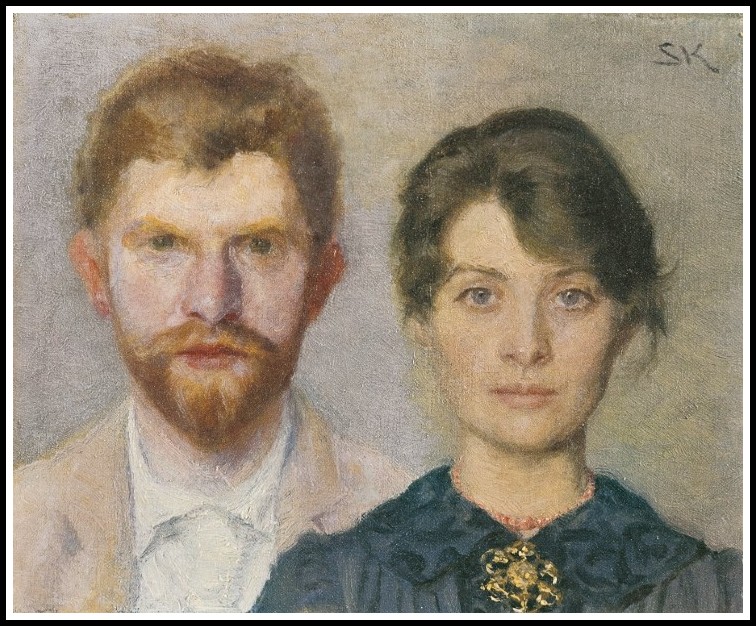

Marie Krøyer, Double Portrait of Marie and P.S. Krøyer, 1890

Hedda & Løvborg? Hedda could never have exhibited such sexual confidence.

Toril Moi continues:

‘Missing in all these productions were the despair, the yearning for beauty, the depth of soul that give Ibsen’s Hedda her complexity and grandeur. I am inclined to see such high-profile productions of Hedda Gabler as symptoms of a postmodern anxiety about seriousness and deep feelings. Such productions respond to what the Norwegian writer Dag Solstad calls “the 19th century’s quite specific form of seriousness” by trying to repress it. Turning the play into fast and brilliant surface, such directors reveal their fear that Hedda Gabler is no longer relevant, that contemporary audiences simply won’t be able to relate to Hedda’s existential despair or her idealist yearning for beauty.’

Elin Danielson-Gambogi, Self-Portrait, 1900

Toril Moi concludes:

‘Such a postmodern emptying out of the play would have made no sense to the women who cried and moaned during the first matinée performances in London in the early 1890s. “Hedda is all of us,” one of them declared. Postmodern directors, however, do their utmost to block identification, usually because they take as gospel the highly questionable idea that someone who identifies with a character necessarily must take that character to be real and thus fail to realize that she is dealing with theatre. But if we aren’t capable of seeing the world as Hedda sees it, if only for a moment, we won’t be able to acknowledge her plight of soul and body. If this—trying to see the world from the point of view of another—is identification, we need it to understand the play. Above all, we need it to understand why Hedda kills herself.’1

As consumerism favours sensation over feeling, ready-made ideas over rigorous thinking, novelty to the genuinely new—in a word, surface over depth—the fast pace and superficiality, the techno-gimmickry and audience-flattery, of ‘postmodern’ productions keep the theatre in business. Shakespeare appealed to both aristocrats and groundlings: in one and the same play he produced entertainment and art. Playwrights still aspire to this ideal: directors in the mainstream place their bets on the groundlings. Today, ‘postmodern Hedda’ is ‘safe after-dinner entertainment’ for one and all.

1 – Toril Moi, ‘Hedda’s Silences: Beauty and Despair in Hedda Gabler’. Modern Drama, 56:4 (Winter 2013) p. 435

Sabine Lepsius, Self-Portrait, 1885

And now we are ready to address our opening question: How did Thomas Langhoff, in his television production of Hedda Gabler, succeed in breathing new life into naturalism? To start, he gave himself an excellent set to work in: a large interior, laid out as Ibsen intended, its windowed doors giving out on a spaciousness beyond. Groupings of furniture against varied backgrounds subdivide the room, each brought to life by well-placed props. The camerawork, never merely functional, articulates the space; lingering on a face to dramatic effect, moving in harmony or counterpoint with emotion, it serves the actors in their work. And this brings us to the essential: Langhoff’s naturalistic Hedda succeeds primarily because of the brilliance of its acting and the ingenuity of its staging, the two working closely with the camera. Unlike in the van Hove production, for example, where the actors often do not act but simply recite their lines (very postmodern!), leaving the dialogue to do all the work, here, in Langhoff, voice and body, word and gesture, are intimately entwined. Even allowing for the fact that playing to the camera instead of to a theatre audience allows the actors to be more natural (no need to project the voice, broaden the gesture), what is impressive in this production is the way, especially in the heightened dramatic moments, Hedda and Løvborg (to mention but the two of them) seem to have weighed every word before speaking it, giving it just the right weight in the phrase. There are no histrionics—even the drunken Løvborg comes across as organic, not as an actor doing a number.

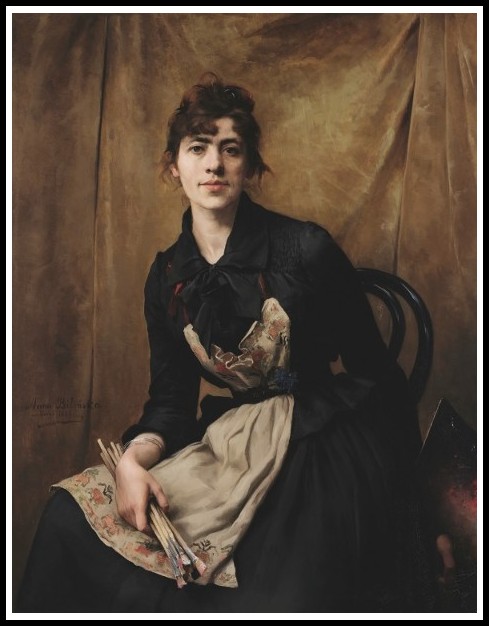

Anna Bilinska Bohdanowicz, Self-Portrait with Palette, 1887

Jutta Hoffmann’s performance as Hedda is particularly fine; rich, subtle, and detailed, it conveys the heroine’s interiority without recourse to grand gesture or raised voice. She demonstrates in acting a truism of music: ‘the most formidable musical task for a pianist is not the playing of a bravura piece, but rather to play a slow movement from Beethoven, Mozart or Schubert—to play it well, with perfect nervous and sound control’. When she burns Løvborg’s manuscript, for example, she has no need to say, ‘Now I am burning—I am burning the child’: she shows it with her eyes, and by the way, hugging her knees, she huddles beside the fire. From this moment on, everything she says and does takes on an air of both despair and the diabolical—precisely what Ibsen indicated, and precisely what the other productions studied here failed to produce. Without this duality of despair and the diabolical, Hedda is not Hedda Gabler. And when she learns that Løvborg’s bullet hit him in the groin, she doesn’t do a fortissimo but delivers her line sotto voce: ‘Oh, something ludicrous and base settles like a curse over everything I touch’: a tone more akin to a Macbeth soliloquy than to a banal domestic melodrama.

Leis Schjelderup, Self-Portrait, 1886

All the actors are excellent. They maintain the naturalist illusion (suspension of disbelief) by the conviction in their acting. They don’t merely occupy space, they inhabit it; they don’t merely pass time, they feel its flow. In their dialogues, they aren’t only listening for their cues, they are listening to what the other is saying. There’s a marvelous realism in their gestures, a grounding of feeling and thought in the body. They manifest a refreshing humility, their acting is utterly natural and unaffected (the opposite of postmodern acting): one senses their confidence in both Ibsen and Langhoff is absolute. Indeed, nothing they say or do is merely expedited; instead, one senses that in their least word and smallest gesture they are ‘in the moment’. They restore duration to time, place to space, and find grace in making plain their humanity. And their collaboration with the director produces wonders. For example, the scene where Hedda tells Tesman she’s burned Løvborg’s manuscript begins with the two of them standing side-by-side next to the sofa, facing the camera, and ends with Hedda seated on the sofa and Tesman on his knees, the actors having modulated their postures and gestures as a composer modulates his keys. Finally, I’ll mention that the use of props is brilliant. Three examples: Tesman balancing Aunt Julia’s parasol on his fingertip as she interrogates him about the prospects for a baby; the magnification of Hedda’s eye in a hand mirror as she gets her guns from the cabinet; the drunken Løvborg struggling to grasp a loose button dangling from a thread on his cuff.

Borghild Røed Lærum, Self-Portrait with Blue Anemone, 1904

I don’t know by what miracle this artistically ambitious naturalist production emerged fully realized from the East Berlin of 1980. It has nothing to do with ‘socialist orthodoxy’ nor is it ‘a beacon of light in dark times’. It doesn’t flatter the audience, it doesn’t pander to their baser instincts; it doesn’t assume life is cut and dried, it doesn’t let the spectator believe he/she is the good guy. In a word, it doesn’t do what the debased naturalism of the mainstream does: it is not safe after-dinner entertainment. While my artistic taste ‘only wants tomorrow, with its promise of something hard to do’, 1 I do occasionally ask, ‘Ain’t there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?’.2 At any rate, between the superbly realized naturalism of Thomas Langhoff and the half-baked, twice-warmed-over pot-pourri of postmodernism, I do not hesitate. Langhoff’s Hedda Gabler is both true to Ibsen and true to life; whether it’s true to the times simply doesn’t matter. What counts is that he gives us, thanks to superlative acting and ingenious staging, a Hedda who is neither victim nor vamp, neither easy to accept nor easy to forget. He gives us Hedda Gabler, he gives us Ibsen’s glorious creature.

1 – David Bowie, ‘Teenage Wildlife’, Scary Monsters and Super Creeps (RCA, 1980)

2 – David Bowie, ‘Young Americans’, Young Americans (RCA, 1975)

Helene Schjerfbeck, Self-Portrait, 1885

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments