I. INTRODUCTION | II. HEDDA GABLER: PSYCHOSEXUAL DYNAMICS | III. FOUR RHYMES FOR HEDDA GABLER | IV. JOHN CALE: HEDDA GABLER

HEDDA GABLER, IBSEN’S GLORIOUS CREATURE

PART 1 – HEDDA GABLER: FEMININITY & PSYCHOSEXUAL DYNAMICS

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

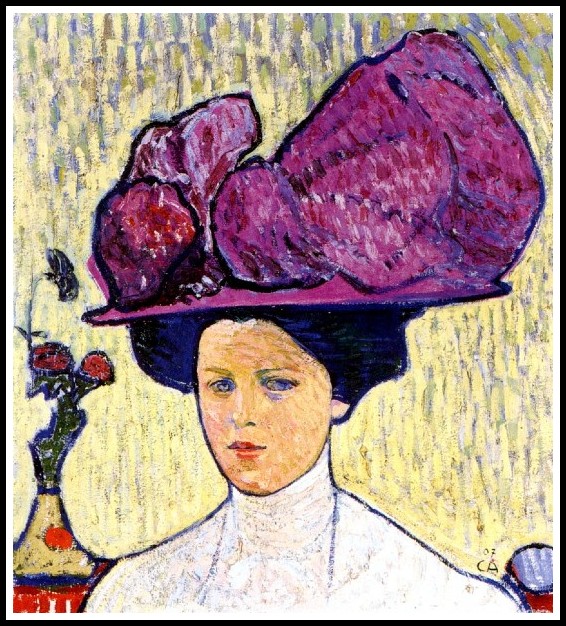

John Duncan Fergusson, In the Sunlight, 1907

I. INTRODUCTION

Hedda Gabler, Ibsen’s (anti-)heroine, fascinates. Why? This is the question this essay, the first of 3 posts on Hedda Gabler, will address. It will focus on Hedda’s struggle to come to terms with the difference between the sexes, and will offer an interpretation of the play (Part 1). Most productions of Hedda Gabler fail to deliver the excitement Hedda’s capacity to fascinate deserves. Why? This is the question the second post* will address, and in doing so it will examine its mise-en scène, focusing on the problem of staging a classic work today (Part 2). I will demonstrate, in a third post*, how the Norwegian National Ballet’s production of Hedda Gabler rises above all the rest, delivering a Hedda who unfailingly fascinates and in so doing, renders all the richness of Ibsen’s play (Part 3).

* Hedda Gabler posts 2 & 3 will be published by the end of December 2022.

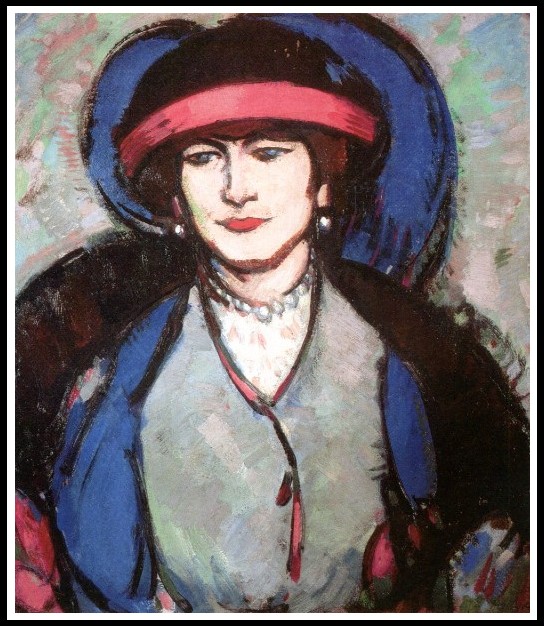

John Duncan Fergusson, The Blue Hat, Closerie des Lilas, 1909

II. WHY DOES HEDDA GABLER FASCINATE? — PSYCHOSEXUAL DYNAMICS

Hedda has a hold on us. Obsessively we return to her, as we return to the scene of a crime. Wherein lies our bewitchment? How does she cast her spell? Enslaving the faculties of the reader, depriving the spectator of resistance, how does she, despite her mediocrity, inspire a certain awe? It is my contention that Hedda fascinates because Ibsen situates her in the very middle of the primal scene of fascination: the difference between the sexes. All of us, from earliest childhood on, are fascinated by this difference, and how we deal with it contributes to forming our ‘character’. Now what, in a word, is Hedda’s character? ‘She’s a bitch’, you might say, and who could disagree? The fact is, however, that if Hedda’s got a problem, Ibsen’s art makes her irreducible to it. You might say, ‘She’s got a bad case of penis envy’; or, ‘She’s hysterical, she’s frigid’; or simply, ‘She’s a flirt who could do with a good fuck’. Again, who could disagree? We need to remember, however, that ‘what is of interest to someone—what Freud called their “preconditions for loving”—is both recondite and profoundly idiosyncratic, a function of the strange weaving of personal history and unconscious desire.’* If Hedda continues to fascinate us, it is because, just like her, we too are obsessed with the difference between the sexes. The difference between Hedda and us is that she can only act out her obsession on page or stage, while we, thanks to her, can give ours free rein in fantasy and imagination. What does Hedda say and do, what does she leave unsaid, in her investigation of sexual difference? In a bid to understand this glorious creature, let us now examine that.

* Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery (NY: Vintage Books, 1998) pp. 68-69

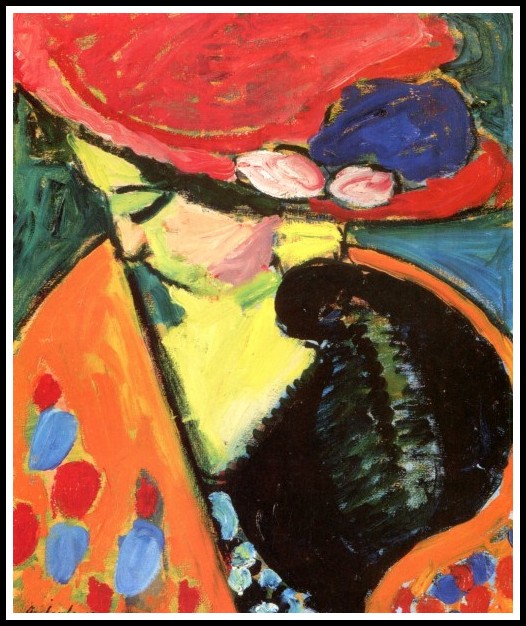

John Duncan Fergusson, Le voile persan, 1909

– And all those – those oblique questions you asked me.

– Which you understood so perfectly well –

– To think you could sit there and ask me such questions! So brazen, so bold!

– Oblique, if you please.

– Yes, but brazen all the same. To question me about – about such things!

– And – that you could answer me, Mr Løvborg.*

It’s all to Hedda’s credit that, to gain sexual knowledge, she exploits her complicity with Løvborg. After all, back from the ballroom, alone in her bedroom, her finger on the trigger between her legs could only teach her so much. What, one wonders, were her ‘brazen questions’? We assume she already knew the ABCs, but how much more of the alphabet of eros did she coax out of Løvborg? And did she go on to learn some Latin? Or the grammar of kisses? And how about foreign languages—postillionage, pompoir, florentine, flanquette? Løvborg, an habitué of the bordello, presumably could indicate many paths to pleasure. But when, with the virginal Hedda, he wanted to move from social to physical intercourse, she fingered the trigger of her Daddy’s pistol and pointed the single-shot flintlock phallus at him. She didn’t want to be left holding the baby, you might say, or risk a scandal that would make her Daddy even more déclassé. And yet her body ached for Løvborg’s embrace—‘My not daring to shoot you, that wasn’t my worst act of cowardice that night’*—and so she forewent the fuck that may have transformed her, deepening her bitterness.

* Henrik Ibsen, Hedda Gabler and Other Plays, translated by Deborah Dawkin & Erik Skuggevik (Penguin Classics, 2019) pp. 336-37

John Duncan Fergusson, Anne Estelle Rice, 1908

Having foreclosed the sexual road to self-affirmation, Hedda must seek affirmation elsewhere. But where? Work is not an option: given her standing in society, it’s a non-starter. The arts might offer an avenue, music might soothe the soul—but it’s her body that needs relief. The hinge of her thighs against a hot-blooded horse, that’s what she craves; that, and a pair of dueling pistols to echo the bang of blood in her brain. Her ballroom days are over. Along comes Tesman. Sexy as a man in socks, a doctorate in ancient dust. Between the pages of a book or between a woman’s legs, where do you think he’d prefer to bury his head? Hedda knows the answer. Still, she marries him. Why? One thing led to another, she tells the predator Brack; a bit of idle talk and she ended up in a trap. Now, excluded from culture and creation (or is it she who turned her back on them?), she finds refuge in flirty conversation. So, she’s a cock-teaser—does that mean she’s content? No. Despite that damned cuckoo distending her belly, the heat of her loins still burns a hole in culture: Tesman’s verbiage can’t touch her, nor can Løvborg’s logorrhea. And now, unwilling to be Brack’s mistress, she is looking for a master: not finding one, she determines to sabotage the sexual order by opting out of the game.

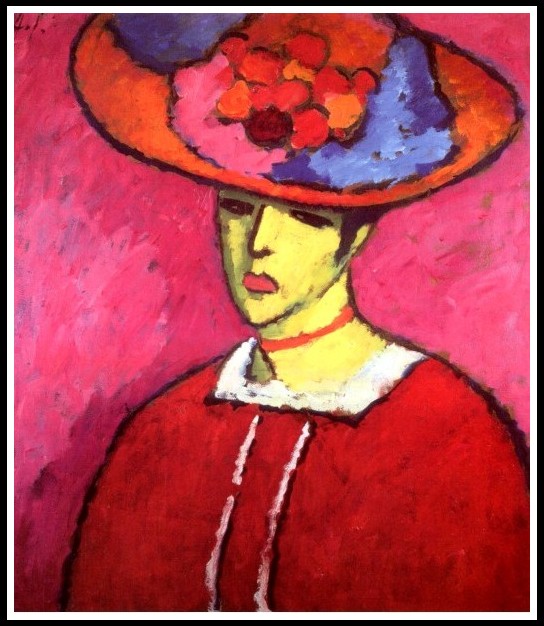

Alexej von Jawlensky, Tête inclinée, 1909

Tesman is myopic, Løvborg nostalgic, and Brack a predator in search of prey. For Tesman the house is a display case for Hedda, for Løvborg it’s a cage from which he can help her escape, and for Brack it’s simply a scene for seduction. Where does that leave Hedda? She disdains the beauty Tesman praises, she can’t abide the ‘lust for life’ in which Løvborg would engulf her, and Brack’s vision of sex, coffee and cigarettes is an affront to her need for eros as self-awakening. If she can’t befoul her beauty physically, to spite her suitors she’ll do it metaphorically: to the hilt she’ll play the bitch. The higher Tesman elevates her on a pedestal, the deeper she debases him. The more Løvborg reminds her of what could have been, the more she forecloses the future. And the more Brack closes in on the prey in his trap, the more radically she resolves to escape him. And so for Tesman she poisons her tongue with bile, for Løvborg she sets his magnum opus aflame, and for Brack she turns her litheness into rigor mortis. The baby with the bathwater. And yet, all along, Hedda only wanted to be loved for what she hoped to become: herself. And therein lies the tragic dimension of Hedda Gabler, heroine and play: the sabotage of her investigation of sexual difference by her own alienation from herself.

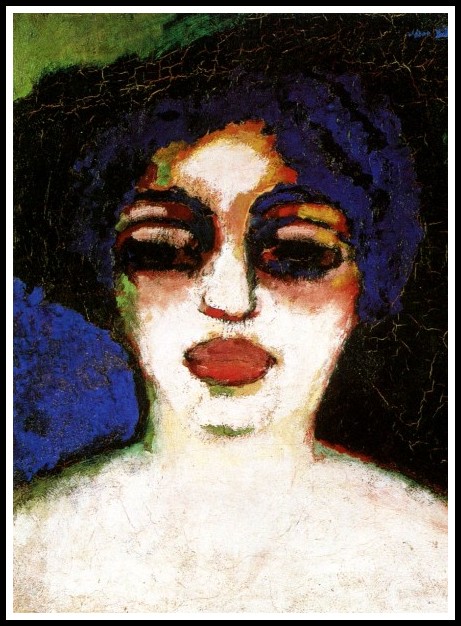

Alexej von Jawlensky, Schokko, 1910

Where did Hedda go wrong? If her desire to ‘be a man’ was a desperate attempt to dissolve the anxiety and frustration that beset her, an attempt to fill her inner void, then her way of dealing with the envy that expressed it undermined any chance that it might succeed. In trying to understand Hedda, we note that while General Gabler’s presence looms throughout the play, Hedda’s mother is conspicuously absent. Deprived of the maternal breast that might have allayed her envy, Hedda, having grown up in a world of horses, boots and pistols, has been left with a feeling of deficiency. On what occasion did Hedda encounter the other sex? We don’t know, but we can be sure that when she did, it occasioned the awakening of her own sex. When did she experience her first orgasm? We don’t know, but we can suppose it was when riding a horse. Free from any maternal interdiction, Hedda was free to bask in her father’s virility. In trying to be the other sex, rather than to discover herself through it, Hedda foregoes an opportunity to fulfill her humanity.

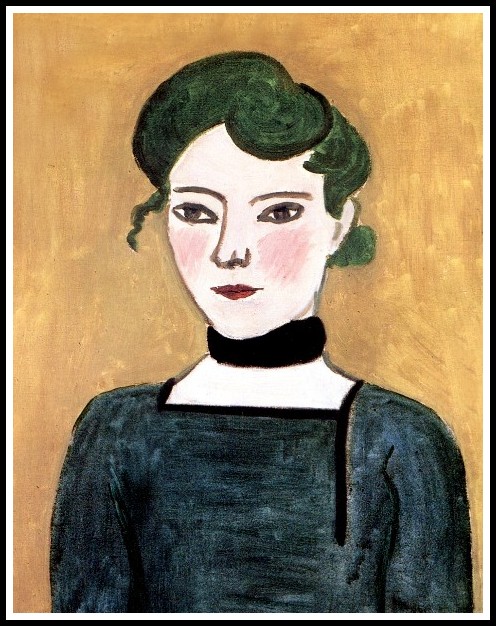

Matisse, Portrait de Marguerite, 1907

Alone in her bedroom we can suppose Hedda’s hand often finds itself in the hinge of her thighs. We can also suppose she’s crying while she’s doing it. Why? Because she doesn’t like the person she’s become. Every symptom is an attempt at self-cure. Hedda’s attempts to resolve the conflict raging inside her (how to situate herself in sexual difference) preclude her from satisfying her greatest desire: to accomplish an authentic act, to achieve an orgasmic union with a man. Rub-a-dub-dub, Hedda’s in a tub, and who do you think are peeping at her? The butcher, the baker, the candlestick-maker, and the general himself, Daddy Gabler. If, with one gunshot, Hedda freed herself from Brack’s trap, in the 29 years that preceded that day, she never managed to free herself from her own. ‘Out of the struggle with others one makes melodrama; out of the struggle with oneself one makes tragedy’. If you want to find the tragic in Hedda Gabler, here is where you must look.

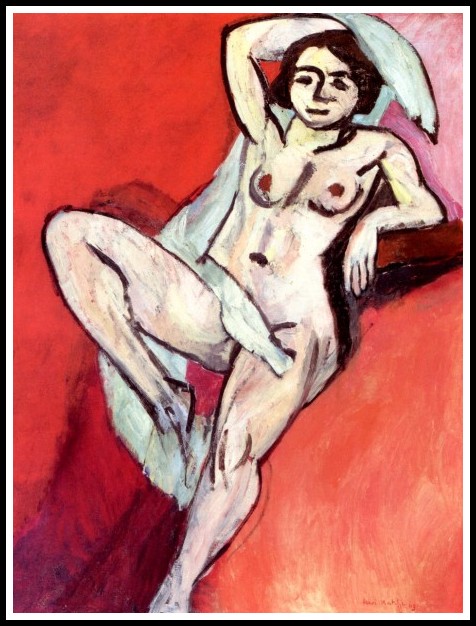

Matisse, Nu à l’écharpe blanche, 1919

As Hedda lies face-down on her bed, her hand between her legs, the gap between hallucinatory wish-fulfilment and kicking her heels till satisfaction is bridged by pain: masochism presides at the ceremony. The play’s circumlocutions, its coy sexual allusions, may lull the lazy spectator into a vision of sex bereft of its diabolical dimension, its potential for disruption: Hedda would never have put a bullet in her brain if her experience of sex was as sanitized as the audience expects. And if, as we may suppose, Hedda is but a vessel for Tesman’s self-relief while Løvborg might have procured her a certain satisfaction, what Hedda needs is a demon lover, a man who can wrench her femininity from her body—a man who can make her a woman. The difference between the sexes is paradigmatic of all differences. Had Hedda come to terms with sexual difference, her life would have been radically altered. Concretely, we may reasonably suppose that her disposition made it very difficult for her to accept penetration. To open herself up, to submit to a man, to feel the sway of sex while being possessed—this she could not do. In the conflict between the demands of her libido and the resistance of her ego, her imperious will to independence did her a disservice: that mysterious strangeness between her legs stood no chance against the armada of her mind’s defences.

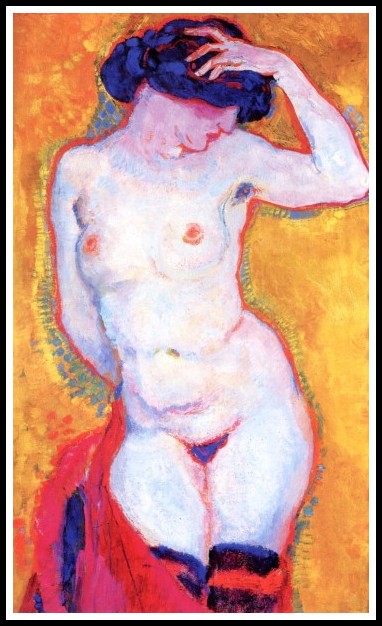

Jan Sluijters, Nu debout (fond jaune), 1911

How might Hedda have found a way out? How might she have averted suicide? The answer, dear reader, is love. Was there not a single man from her ballroom days who she might have loved? A man smart enough to see that beneath her manly facade is a woman struggling to be set free? Women submit out of love. In order for Hedda to love, she’d have to find a man who would see her neither as Madonna nor Whore; not two-bit bitch, not haughty aristocrat, but simply the woman she is in her moments of lucidity alone. Making love with the man she loves, Hedda would offer him her submission, that libidinal submission that is the key to her satisfaction. Instead of tilting at windmills by adopting manly attitudes, she could fight the good fight of female sexuality, confronting the conflict that lies at its core. It wouldn’t be easy—the ego detests being defeated, the magic between her legs demands defeat—scandalously, it demands the masochism that procures orgasm. The conflict between the mind detesting defeat and the body craving it, had Hedda fully engaged it, would have made her not only a woman, but her own person. Nobody’s fool but her own, it would have ‘unfooled’ her. By affirming the difference between the sexes, she might have found vast vistas of pleasure; by denying sexual difference, she foreclosed such a perspective. She never put herself in a position to learn that, for her, when it comes to sex, power lies in surrender, pleasure in the abolition of limits, and self-assurance in loss of control.

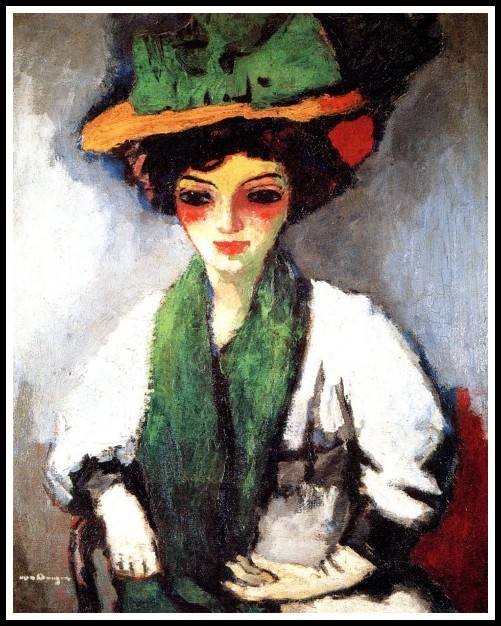

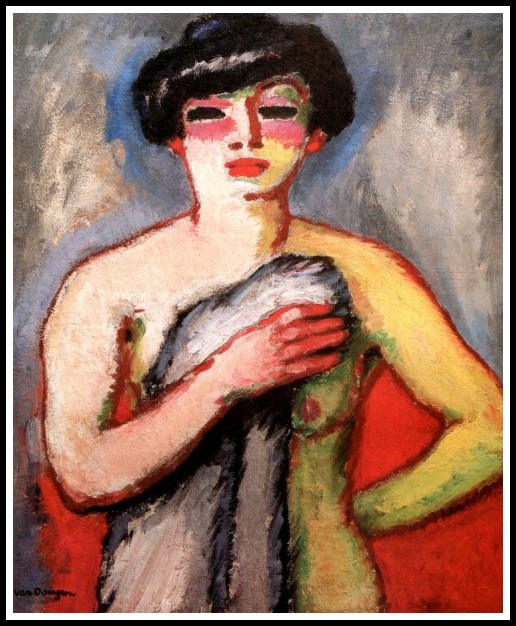

Kees van Dongen, Femme au chapeau vert, 1907

Hedda Gabler’s first victim, then, is none other than Hedda herself. She is, I maintain, a glorious creature, one who fascinates us because the way she negotiates sexual difference compels us to examine how we do the same. For a man, she is fascinating because she offers a window into female sexuality. For a woman, because ‘the work of femininity’ is a never-ending task, she fascinates no less. In the course of a life the vicissitudes of fucking, for both man and woman, entail an alertness to the evolution of the other’s erotic scenario as well as a reconfiguration of one’s own. In these adaptations that lovers are called upon to make, Hedda’s investigations into her sexuality—however violent, awkward and indirect—are stimulating. Yes, I contend, there’s something to be said for a bullet to the brain, a bonfire of words, and a radical intransigence; there’s something to be said for Hedda’s hand between her legs, her placing Mount Ortler on her mound of Venus, her taking Miss Tesman’s hat for the maid’s. And there’s something to be said for an allumeuse in the guise of a mal-baisée. Many find Hedda hard to love. I don’t. There’s something to be said for a ‘beautiful loser’.

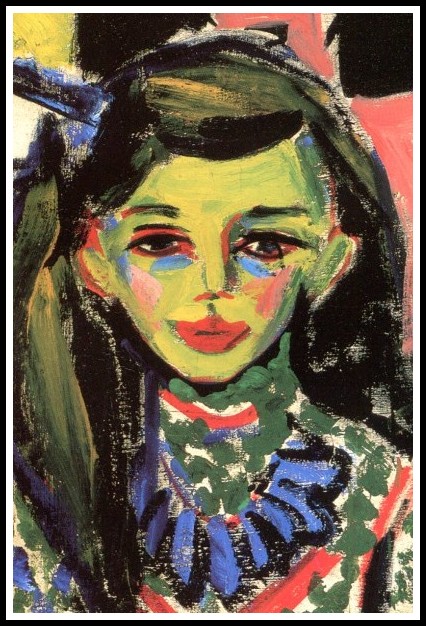

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fränzi, 1910 (detail)

I end this essay with a citation from Richard Eyre’s introduction to his adaptation/translation of Hedda Gabler.1

In the summer of 1889, when he was 61, Ibsen was on holiday in a South Tyrolean village. He met an 18-year-old Viennese girl called Emilie Bardach and fell in love. He’d dedicated himself to his art like a monk, for ‘the power and the glory’, and he’d renounced spontaneous joy and sexual fulfilment. Emilie became the ‘May sun of a September life’. She asked him to live with her; he at first agreed but, crippled by guilt and fear of scandal (and perhaps impotence as well), put an end to the relationship. Emilie, like Hedda, was a beautiful, intelligent, spoilt, bored upper-class girl with ‘a tired look in her mysterious eyes’, who wanted to have power and was thrilled at the possibility of snaring someone else’s husband. The village in which they met in the Tyrol – Gossensass – was mentioned specifically in an earlier draft of the play when Hedda and Løvborg are looking at the honeymoon photographs in the second act, and fragments of dialogue in Ibsen’s notes from the play appear to be derived directly from his conversations with Emilie.

While the suggestion that Emilie Bardach was a model for Hedda Gabler has been much discussed and contested,2 Eyre’s portrait of her still drives home the point that Hedda’s psychosexual dynamics are as active as ever in real women’s lives. Speaking of women’s lives, readers will have noticed that I’ve avoided both socio-economic and socio-cultural contextualization of the play. Besides the fact that Ibsen criticism abounds in such perspective, I’ve deliberately avoided it because, at bottom, it is irrelevant to my argument. For those readers who might disagree, I will take up the issue in Part 2* of this series.

1 – Richard Eyre, ‘Introduction’, Henrik Ibsen, Hedda Gabler, tr. Richard Eyre (London: Nick Hern Books, 2005).

2 – See Joan Templeton, Ibsen’s Women (Plunkett Lake Press, 2015) chapter 10.

* Hedda Gabler posts 2 & 3 will be published by the end of December 2022.

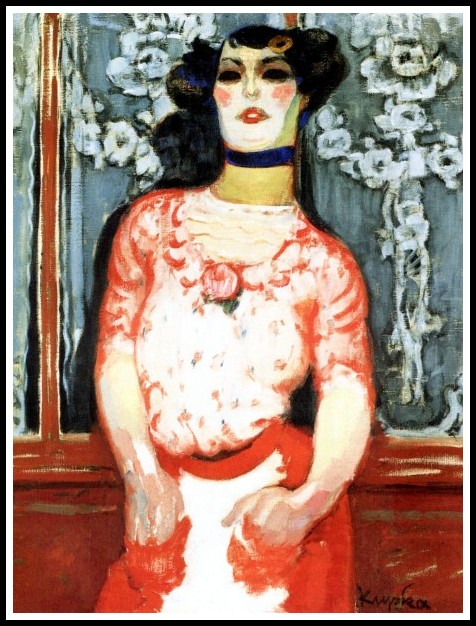

Cuno Amiet, Le chapeau violet, 1907

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The theoretical underpinning of this essay, as well as a number of its formulations, are derived from the work of three French psychoanalysts (who, be it said in passing, all happen to be women):

Murielle Gagnebin, L’Irreprésentable ou les Silences de l’œuvre (Paris: Presses universitaires de France, 1984) pp. 34-57

Jacqueline Schaeffer, ‘The Riddle of the Repudiation of Femininity: The Scandal of the Feminine Dimension’, in Leticia Glocer Fiorini & Graciela Abelin-Sas Rose, editors, On Freud’s ‘Femininity’ (London: Karnac Books, 2010) pp. 129-143

Maria Torok, ‘The Significance of Penis Envy in Women’, in Janine Chasseguet-Smirgel, Female Sexuality: New Psychoanalytic Views (London: Karnac Books, 1970) pp. 135-170

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

III. FOUR RHYMES FOR HEDDA GABLER

I’ve referred to Hedda Gabler—the literary figure on the page, the dramatic figure on the stage—as ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’. I’ve tried to show why she fascinates. Only a poetic discourse, however, not a discursive one, can convey her raging glory. In Part 3* of this series you will find my essay on the Norwegian National Ballet’s version of Hedda Gabler. It brilliantly conveys Hedda’s ‘dark sublime’ in the poetic discourse that is contemporary dance. As a teaser for another kind of poetic discourse, I offer these Four Rhymes for Hedda Gabler, adapted from my literary novel, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms.

* Hedda Gabler posts 2 & 3 will be published by the end of December 2022.

FOUR RHYMES FOR HEDDA GABLER

Richard Jonathan

Oh Hedda, where are you now?

I miss the cut of your ice queen lips

And the diligence of your noblesse oblige

I miss your Sphinx to my Oedipus

Like in Moreau’s masterpiece

Oh Hedda, where are you now?

I miss the tangerine fougère

That scents your mahogany hair

I miss your pearly white breasts

That hesitate between apple and pear

Oh Hedda, where are you now?

I miss your nervous intelligence

Your cold, implacable brilliance

I miss your radical scepticism

Your faith in artifice.

Oh Hedda, where are you now?

I miss you talking in your sleep

Wrapping your troubles in dreams

I miss you flat on your back

Airing your strawberry creams

IV. JOHN CALE: HEDDA GABLER

John Cale’s ‘Hedda Gabler’ captures the hellish majesty of Ibsen’s heroine. The song is a dark hymn to Hedda, at once transcendent and sepulchral, eerie and stately. With its evocation of high culture and its intimation of horror, only a European could have written the song. It has something of Rilke’s ‘beauty is nothing but the beginning of terror’; it is, indeed, an elegy, a lament for the dead. In its long coda I see Hedda alone, a corpse crying cold tears in an empty universe. Testifying to the music’s power, the song—at once a paean to nihilism and a prayer for redemption—fills that vast sidereal void where Hedda, akin to the living dead, searches in vain for sleep.

The song is not available on Spotify, but you can listen to the original recording on youtube. Youtube also offers several versions with orchestra; all, unfortunately, with poor sound and video. The best, which I nevertheless recommend for the innovative arrangement and the scintillating guitar, is the one from John Cale’s 2010 Norwich concert. Note how—like brisk diagonals tearing into a staid rectangle—the strident bowing of the strings, the hit-and-run guitar licks, and the off-kilter drum fills punctuate the keyboard ground, adding just the right touch of violence and menace to the calmness of the keys. (Scroll down to read the lyrics and watch the videos.)

HEDDA GABLER

John Cale

Hedda Gabler

Had a very funny face

Tired of waiting

Tired of the human race

Like her brother

Sitting in the library

Reading how dear Adolph

Was going to save all Germany

Hedda Gabler

She’ll go down in history

Hedda Gabler

Down in all her misery

Like her mother

Married to the bank manager

She took the money

Hung him in the closet for fun

Hedda Gabler

She’ll go down in history

Hedda Gabler

Down in all her misery

Sleep, sleep, Hedda Gabler

JOHN CALE – HEDDA GABLER

HEDDA GABLER – JOHN CALE – ANIMAL JUSTICE (EP, 1977)

JOHN CALE – HEDDA GABLER – NORWICH 2010

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments