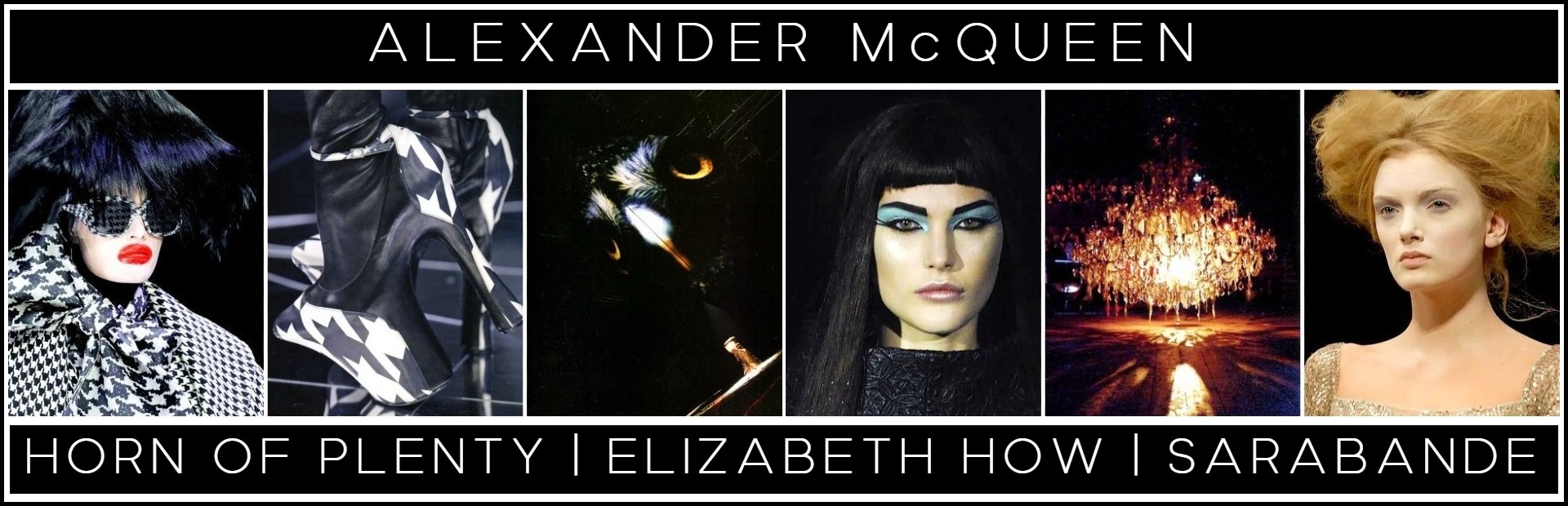

I. INTRODUCTION | II. HORN OF PLENTY | III. ELIZABETH HOW | IV. SARABANDE | V. CODA

A Thematic Analysis

ALEXANDER MCQUEEN: HORN OF PLENTY | ELIZABETH HOW | SARABANDE

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel ‘Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms‘

Alexander McQueen: Sarabande | Elizabeth How | Horn of Plenty | Vogue

I. INTRODUCTION

Fashion, from the perspective of both a designer creating a collection and a person dressing themself, can fruitfully be considered a form of play. This belief underlies my arguments in this essay. In asserting it from the outset, my aim is simply to remind you, dear reader, that fashion, like other dimensions of experience underpinned by play—sex, for example—will always have a ‘remainder’ that escapes capture by whatever one may say about it. So, for example, when I use the concept of ‘hyperconsumerism’ in discussing The Horn of Plenty, bear in mind that I am not implying that fashion can be reduced to consumerism. I aim, then, to use conceptual tools with a light touch: not to impose on but rather to investigate and explore the designer’s art. My ambition is to offer fresh interpretations of the work, or at least of aspects of it. The question of fashion-as-art will come up in this essay. Art, by definition, is open to a plurality of interpretations: I offer mine in the hope you will find them stimulating (leave a comment if you’d like to express your response). Here’s an outline of the essay: Three shows, three themes, three analytic frameworks: Horn of Plenty, hyperconsumerism, ‘fatal strategy’; Elizabeth How, the feminine, the witch; Sarabande, form-and-content, nostalgia. Are you ready? Let’s go!

Alexander McQueen: Elizabeth How | Horn of Plenty | Sarabande | Model: Vlada Roslyakova | Vogue

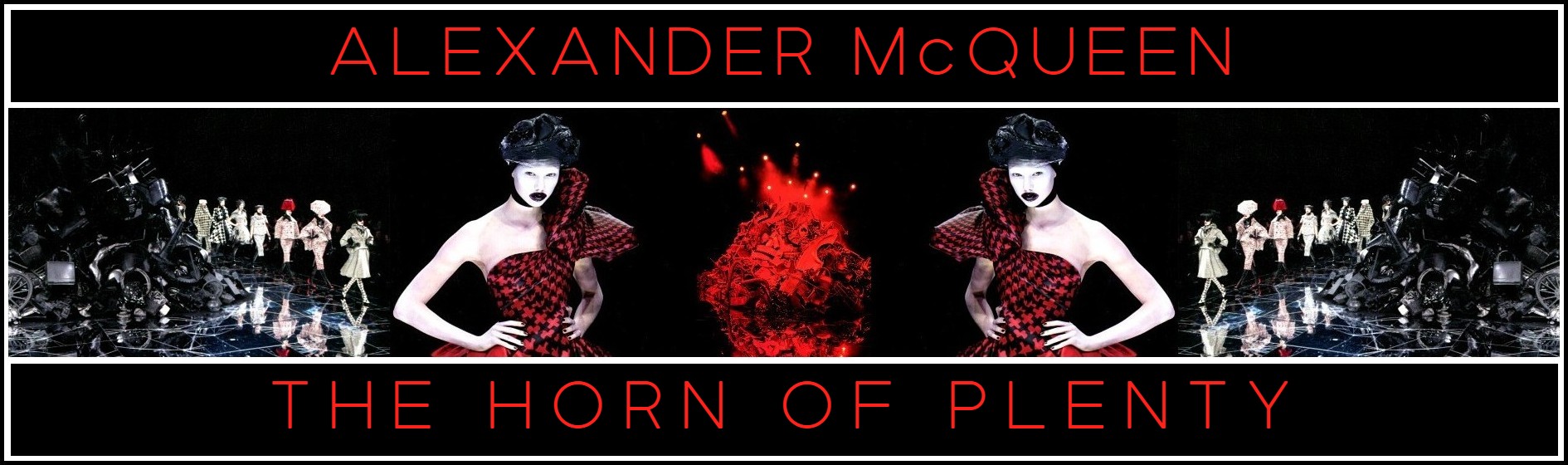

II. THE HORN OF PLENTY | A/W 2009-10

Palais Omnisports de Paris-Bercy, 10 March 2009

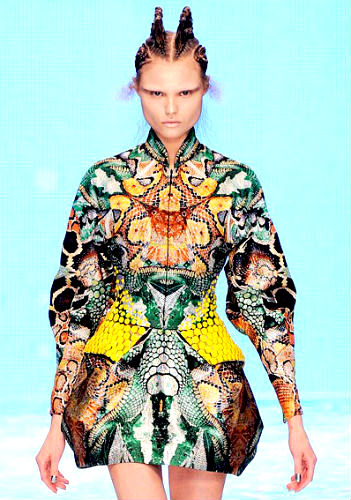

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009-10

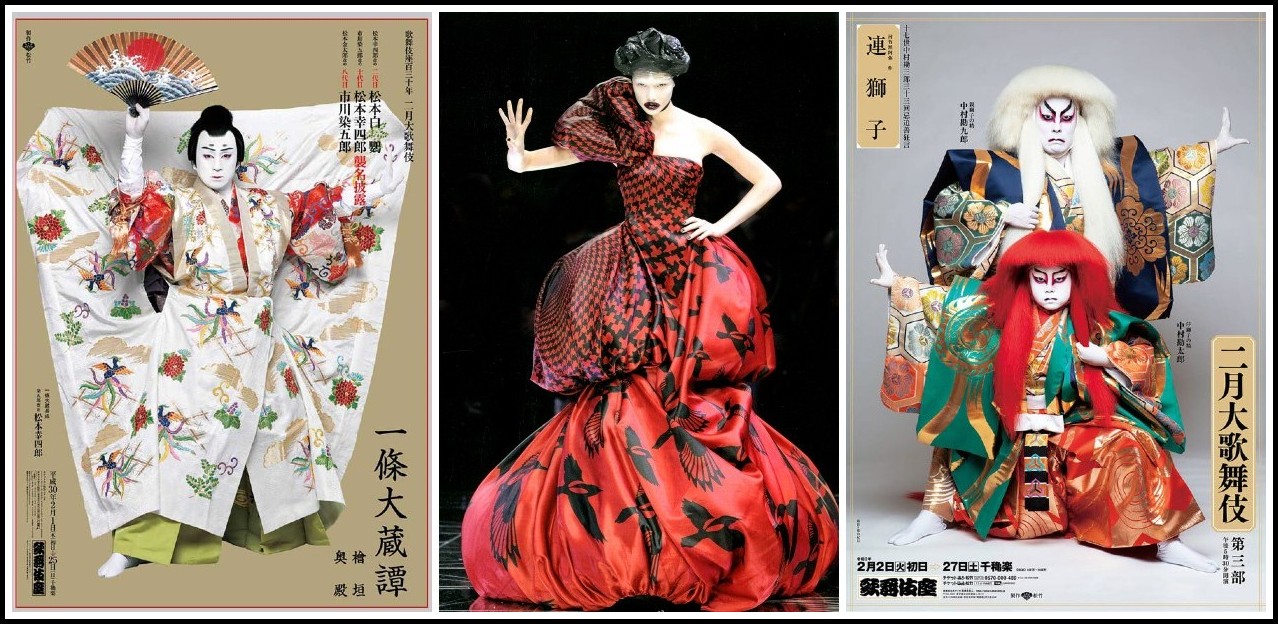

Alexander McQueen’s The Horn of Plenty is a magnificent piece of performance art, as clean in its gesture as kabuki theatre…

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009-10 | Kabuki posters

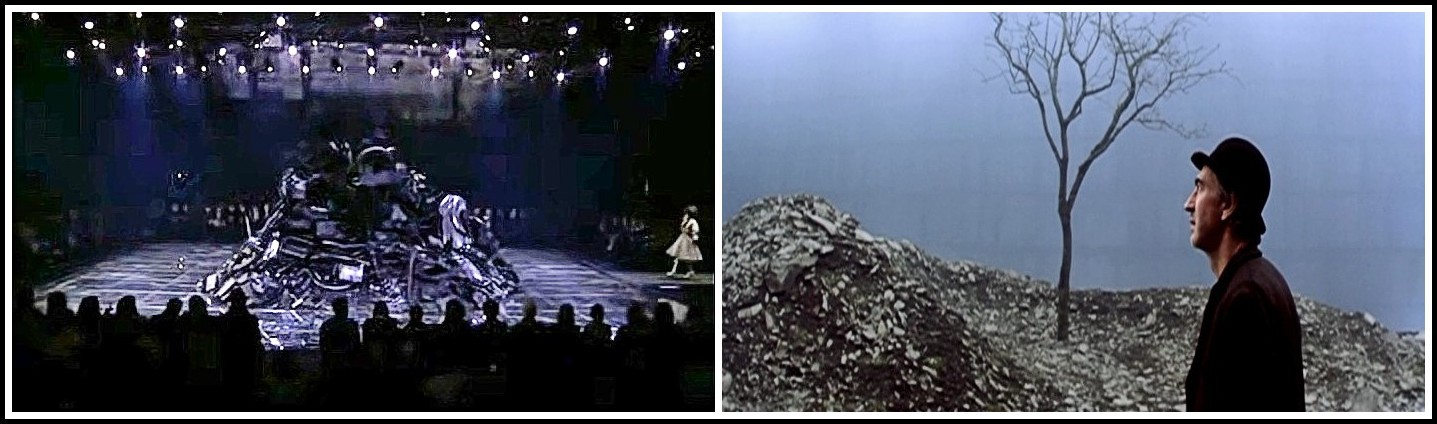

… as minimal in its stagecraft as a Beckett play.

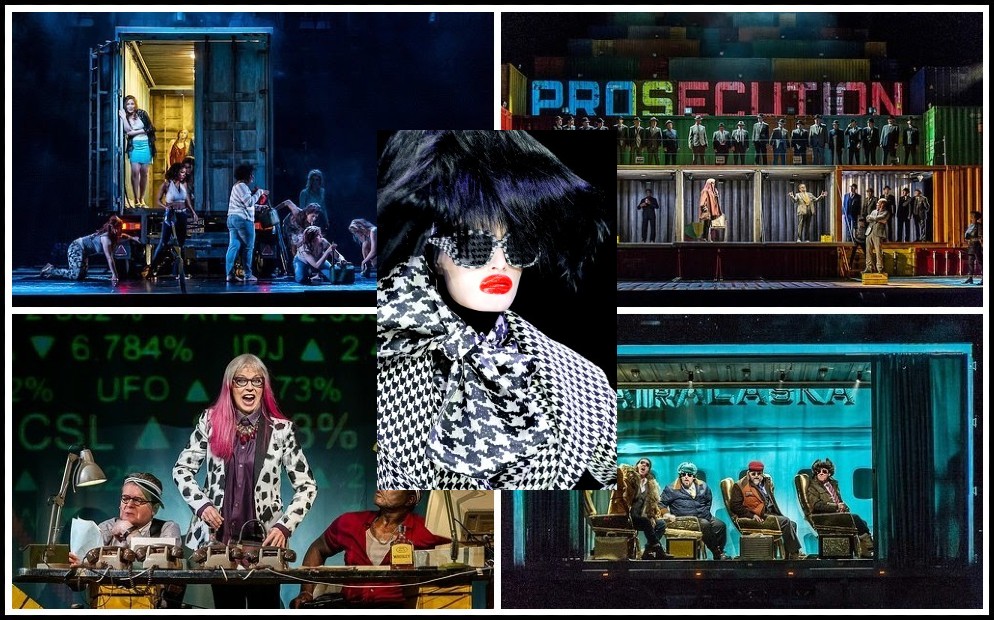

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty | Samuel Beckett, Waiting for Godot

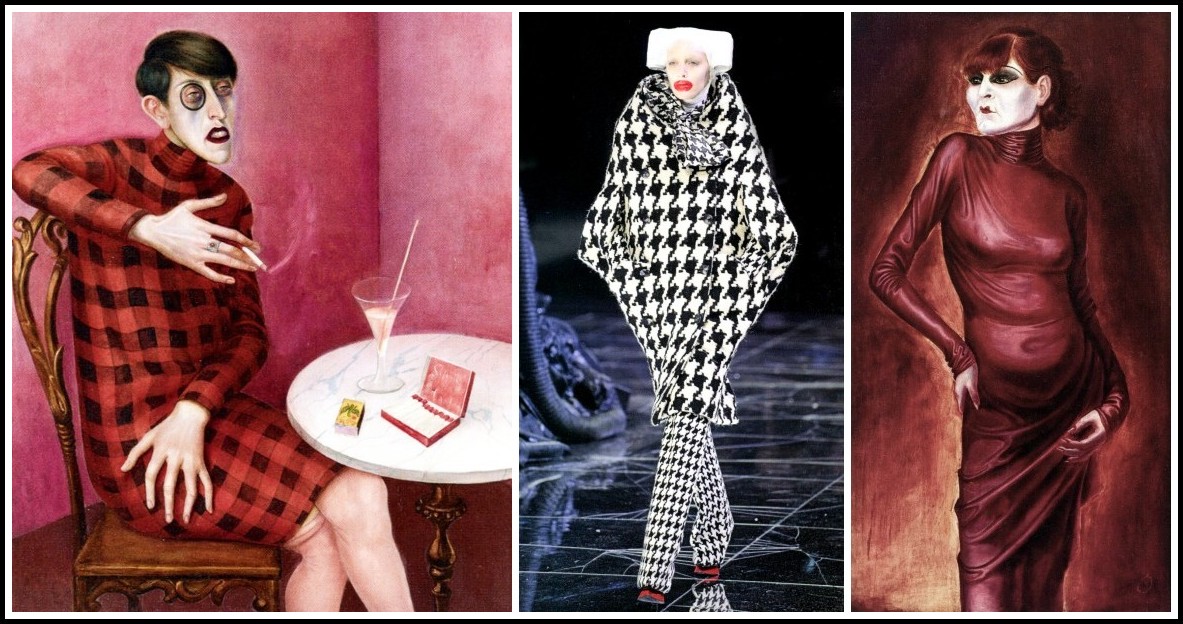

In its matter-of-factness it evokes the Neue Sachlichkeit painters of Weimar Germany…

Otto Dix, The Journalist Sylvia von Harden, 1926 | Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty | Otto Dix, The Dancer Anita Berber, 1925

… while in its vision of fashion as a futile attempt to stop the present collapsing into the past it recalls Brecht and Weill’s opera of the founding of Mahagonny, its surrender to pleasure and its collapse.

The Royal Opera House, The Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny, 2015 | Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009-10

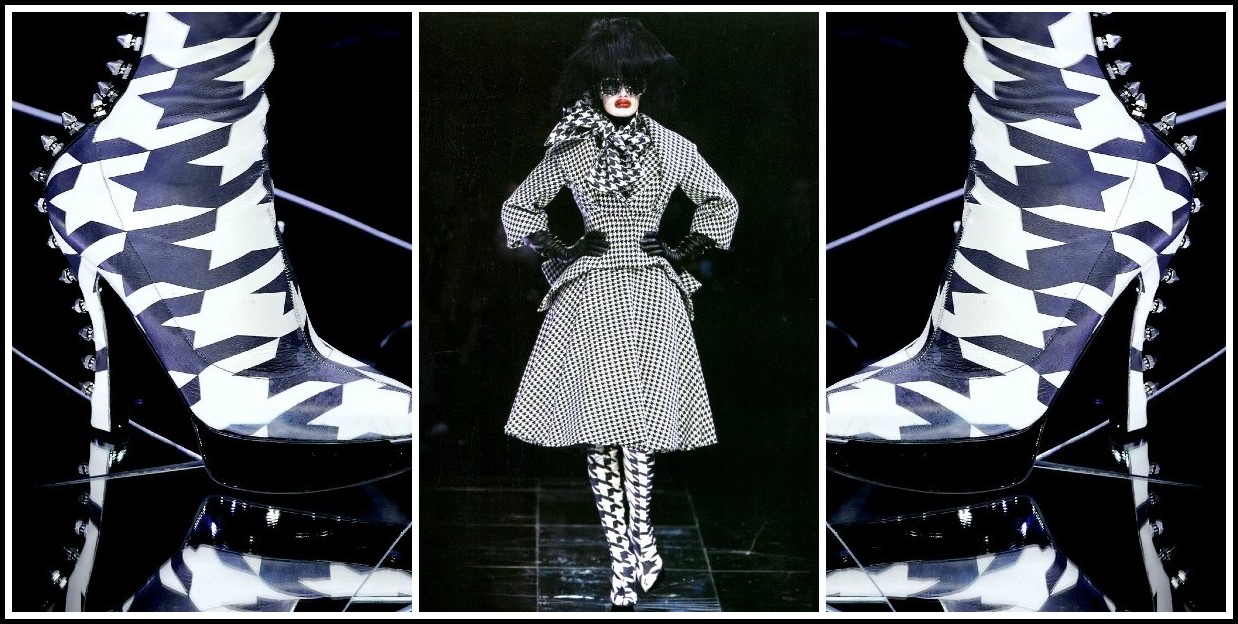

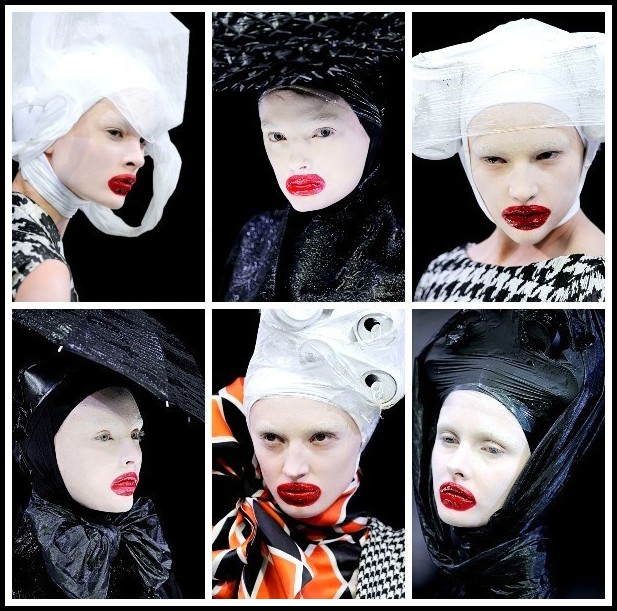

The floor of the Horn of Plenty set is paved in a ragged pattern of reflective glass; rising from the center is a mound of trash painted black. Around this heap the models parade, all sardonic swagger and derisive sass. Under hats of hubcaps or aluminum cans, woven ‘tires’ or garbage bags, their white-powdered faces project lips black or red, lips they barely condescend to form into a sneer. And what are the models wearing? Take the first out, Alla Kostromichova: sloping shoulders, nipped-in waist, full skirt, in hounds-tooth from top to toe: she’s very ‘New Look’. The outfit is perfect, beautifully finished with black gloves and hat, and yet we sense in the elegance there’s something amiss. What might it be? Vaguely we feel that McQueen has deliberately over-egged his pudding.

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Model: Alla Kostromichova | Vogue

Now let’s take a look at a mid-way model, Heidi Mount: the pallor of her face and throat, the whiteness of her hands and arms, evoke a cold, lunar world—the dull white of death—while her black sweater-dress and the knitted coils hatting her head and winding round her neck conjure the chthonian world lying beneath the crust of ‘reality’. It’s a beautifully realized ensemble, but again we sense something is amiss. What could it be? Vaguely we feel that McQueen has transported us into a mythic realm.

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Model: Heidi Mount | Vogue

Finally, from close to the show’s end, consider Polina Kasina’s look: her ruched gown that narrows at the knees is made from a nylon that resembles garbage bag material; her floor length cloak, ‘milled for McQueen from silk and synthetic fibres’,* resembles bubble wrap. Similar to that of her dress, ‘garbage bag material’ coifs her head. By now, we consider ourselves hip to McQueen’s game, but given all we’ve seen, we sense there’s more to this show than fashion, trash and recycling. What might it be? Vaguely we feel that if McQueen has a ‘message’, it’s not as simple as it seems.

* Katherine Gleason, Alexander McQueen: Evolution (Race Point Publishing/The Book Shop, 2012) 203

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Model: Polina Kasina | Vogue

In his New York Times review of The Horn of Plenty, Eric Wilson quotes McQueen as saying before the show: ‘This whole situation is such a cliché. The turnover of fashion is just so quick and so throwaway, and I think that is a big part of the problem. There is no longevity.’ And: ‘People don’t want to see clothes. They want to see something that fuels the imagination.’ Beyond his feeling the pressure of sustaining the pace of productivity the ‘fashion business’ demands of designers, I believe McQueen, in these apparently flippant pre-show remarks, is hinting at something deeper. To try to determine what it might be, we will need to take a look, first, at fashion itself; second, at the current historical moment; third, at the reasons why McQueen resisted certain forces of this moment, and, fourth and finally, at McQueen’s precise strategy of resistance to ‘the fashion business’ as exemplified in The Horn of Plenty.

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Models: Magdalena Frackowiak | Marina Peres | Alana Zimmer | Vogue

‘No one can say that eyes have not had enough of seeing, ears their fill of hearing. What was, will be again, what has been done, will be done again, and there is nothing new under the sun!’ Good old Ecclesiastes. Didn’t know he was such an expert on fashion, did you? Indeed, reading a book on fashion written by an historian— for example, Rebecca Arnold’s Fashion: A Very Short Introduction—quickly makes it clear that in all the areas she covers—designers, art, industry, shopping, ethics, globalization—much of what one had thought of as contemporary actually has a long history. In fact, not only is fashion as old as civilization itself, it is, I would argue, a constituent of it. To look down on fashion because it is frivolous and because ‘fashion lives the paradox of being sustained by disappearances’* would be foolish. Why? Because fashion has a dimension of play that intersects with the play-dimension of identity. If identity is a set of ruses subject to revision, and if fashion is a means to project and play with identity, then fashion is a ruse serving a ruse. To what end? To helping one ‘become who one is’ (as Nietzsche puts it). Identity-as-play, fashion-as-play, is an antidote to dogmatism. A frivolity that enhances our humanity, fashion, then, is an eminently humanizing aspect of our experience. I maintain that any intelligent understanding of it must address the paradoxes that lie at its heart.

* Judith Clark, in Judith Clark & Adam Phillips, The Concise Dictionary of Dress (London: Violette Editions; 2010), 116, 117

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Models: Lily Donaldson | Maryna Linchuk | Kinga Rajzak | Vogue

Having made these remarks on fashion, let us now turn to our second consideration, the ‘historical moment’*. To my mind, the single best description of it is the one made by Jonathan Crary in his 2013 book, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep. I offer here this extensive quote from it:

There is no evading the extent to which the internet and digital communications have been the engine of the relentless financialization and commodification of more and more regions of individual and social life. Today there are numerous pressures for individuals to reimagine and refigure themselves as being of the same consistency and values as the dematerialized commodities and social connections in which they are immersed so extensively. Reification has proceeded to the point where the individual has to invent a self-understanding that optimizes or facilitates their participation in digital milieus and speeds. Paradoxically, this means impersonating the inert and the inanimate. Because one cannot literally enter any of the electronic mirages that constitute the interlocking marketplaces of global consumerism, one is obliged to construct fantasmatic compatibilities between the human and a realm of choices that is fundamentally unlivable. Indeed, there is no possible harmonization between actual living beings and the demands of 24/7 capitalism, but there are countless inducements to delusionally suspend or obscure some of the humiliating limitations of lived experience. For example, products and services that promise to ‘reverse the aging process’ are not appealing to a fear of death so much as offering superficial ways to simulate the non-human properties and temporalities of the digital zones one is already inhabiting for much of each day. Widespread are fantasies of individual survival or prosperity amid the destruction of civil society and the elimination of mutual-support institutions.**

* I prefer the term ‘(current) historical moment’ to ‘late capitalism’, because it is free of the potentially misleading connotations of the latter term. I will only use ‘late capitalism’ when using ‘(current) historical moment’ would degrade the clarity of the sentence.

** Condensed from Jonathan Crary, 24/7: Late Capitalism and the Ends of Sleep (Verso, 2013) 99-101

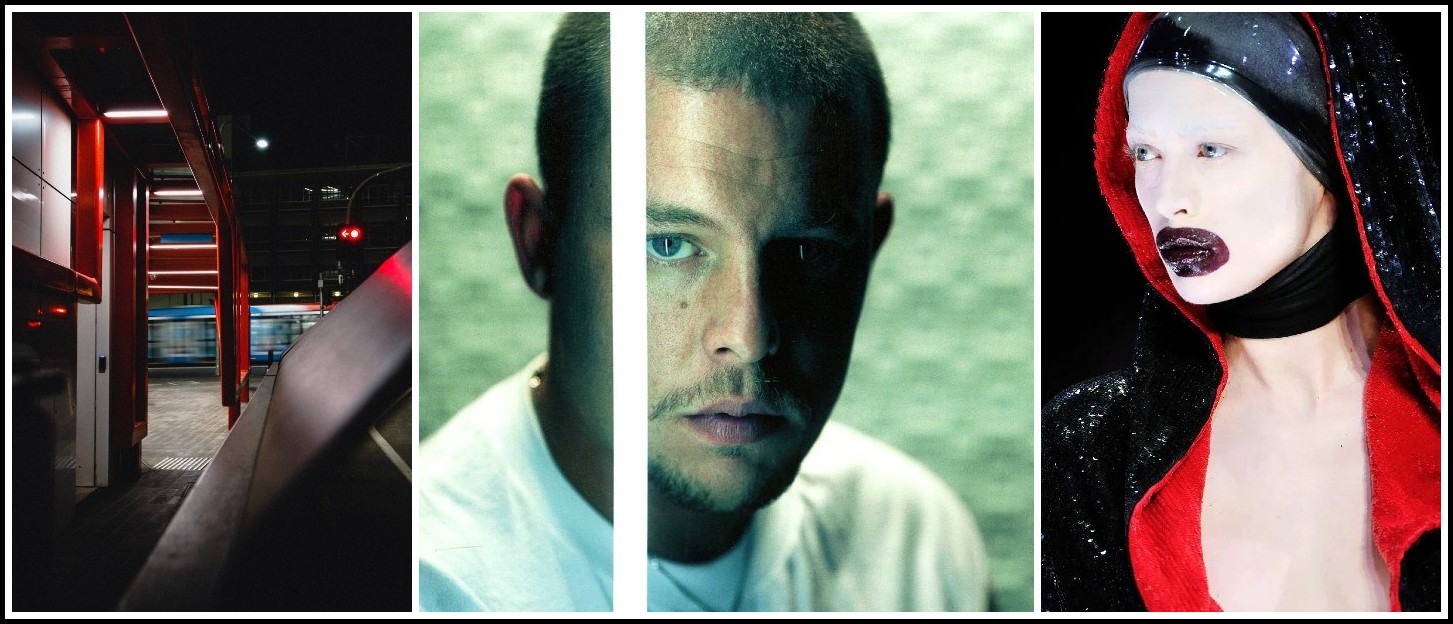

Samuel Rios, Unsplash || Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty | Model: Magdalena Frackowiak | Vogue || Sam Albury, Unsplash

To complement Cary’s description of our ‘civilization and its discontents’, I offer these remarks by Florian Cord that draw on the thought of Jean Baudrillard:

We live in a ‘hyperreality’ in which the reality principle is cancelled, simulacra of a new kind proliferate vertiginously and signs as well as money float freely. Moreover, in this hyperreality, the distinction between real and imaginary, true and false, authentic and fake can no longer be made. The stylized character of all events, things and actions, point to their derived, secondary nature. It is an order from which virtually all negativity and singularity have been eliminated.*

* Condensed from Florian Cord, J.G. Ballard’s Politics: Late Capitalism, Power, and the Pataphysics of Resistance (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018) 5, 9, 30, 33

Johann Walter Bantz, Unsplash | Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty | Vogue

Now, having given a capsule description of the historical moment, let us turn to our third consideration, ‘the reasons why McQueen resisted certain forces of this moment’. It is my conviction that much in his shows and collections can be considered art. McQueen, then, was an artist, the kind of artist who was driven to tackle his demons through the process of creating art. Such artists do not make workaday art; instead, they push limits, they take risks, they affirm their individuality. In doing so, they evolve a style that bears their signature.* Alexander McQueen killed himself. Throughout his life he upheld the values of art.**. Could it be that he felt the hyperreality of fashion could not sustain him upon the death of his mother? Could it be that he felt the zombification induced by hyperconsumerism precluded the traumatized child within him*** from co-existing with the adulated adult he’d become? Could it be, finally, that he could no longer ‘construct fantasmatic compatibilities between the human and a realm of choices that is fundamentally unlivable?’ These questions will forever remain unanswerable, but one only has to look at McQueen’s work and read the interviews he gave to find evidence that he resisted ‘certain forces of the historical moment’ for reasons such as these.

* In some cases, when things work out, they either stop making art to devote themselves to the business of living (Rimbaud, Lennon) or move on to a more serene form of art-making (Henry Miller, Jean Genet). In other cases, when things don’t work out, they kill themselves (Van Gogh, Sylvia Plath, Francesca Woodman, Paul Celan, Nicolas de Staël, Diane Arbus, Unica Zürn) or crash out (Fassbinder, Serge Gainsbourg, Jim Morrison, and Louis Kahn).

** For the sake of concision, one could subsume the values of art under this formula: to honour the individual against the crowd, to honour the ‘real’ behind the appearance, to honour the life-spirit against all that deadens it.

*** See Voss in Alexander McQueen: Feminine, Femininity, Feminist

Apollo Photography, Unsplash | Alexander McQueen by Joseph Cultice | Alexander McQueen, Horn of Plenty, Vogue

Now, having sketched out the reasons why McQueen resisted ‘certain forces of the historical moment’, let us turn to our fourth and final consideration: the designer’s precise strategy of resistance as exemplified in The Horn of Plenty. The challenge McQueen faced in resisting hyperconsumerism was, of course, the fact that fashion is a primary vehicle for the promotion of it. The reception of his earlier shows and collections had, I believe, taught him that in our hyperreal world ‘the received forms of resistance are fundamentally ineffective’*; in other words, that ‘radicality has lost its transgressive potential’ simply because ‘the recuperative power of late capital is inexhaustible’. (Look around you: See that dame in distressed jeans or a punk outfit bought from a luxury store?) McQueen, then, was well aware of ‘the exhaustion of established modes of political action’. He understood that effective resistance demanded something different, that a ‘trans-political form of subversion’ was what was required. In response to this requirement, he adopted what Jean Baudrillard called a ‘fatal strategy’, a strategy that ‘does not aspire to “go beyond” the system in any way, seeking some kind of alternative; instead, it fully remains on the system’s terrain, attacking it with its own weapons, pushing its own logic to the extreme’. This, then, is precisely the form of resistance McQueen enacts in The Horn of Plenty.

* This phrase, as well as the others between quotes in this paragraph, are drawn from the introductory chapter of Florian Cord, J.G. Ballard’s Politics: Late Capitalism, Power, and the Pataphysics of Resistance (Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2018)

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Vogue

Remember Alla Kostromichova’s look that we discussed earlier? ‘We sense in the elegance there’s something amiss. What might it be? Vaguely we feel that McQueen has deliberately over-egged his pudding’. Indeed, as one look follows another, the ‘exaggerated’ nature of the collection becomes obvious. In Kate Bethune’s brief review of The Horn of Plenty*, for example, we find the following descriptive terms: drama, hyperbole, theatrical, exuberant, excess, oversized, exaggerated. And we find the following interpretive terms: subverting, irony, parody, political undertones, lampooning. Exaggeration as an artistic and/or political strategy, typically referred to in the critical idiom as the ‘grotesque’, is, of course, a common practice with a long history. To what end is McQueen employing it in The Horn of Plenty?

* Kate Bethune, ‘The Horn of Plenty’ in ‘Encyclopedia of Collections’ in Claire Wilcox, editor, Alexander McQueen (London: V&A Publishing, 2015) 320

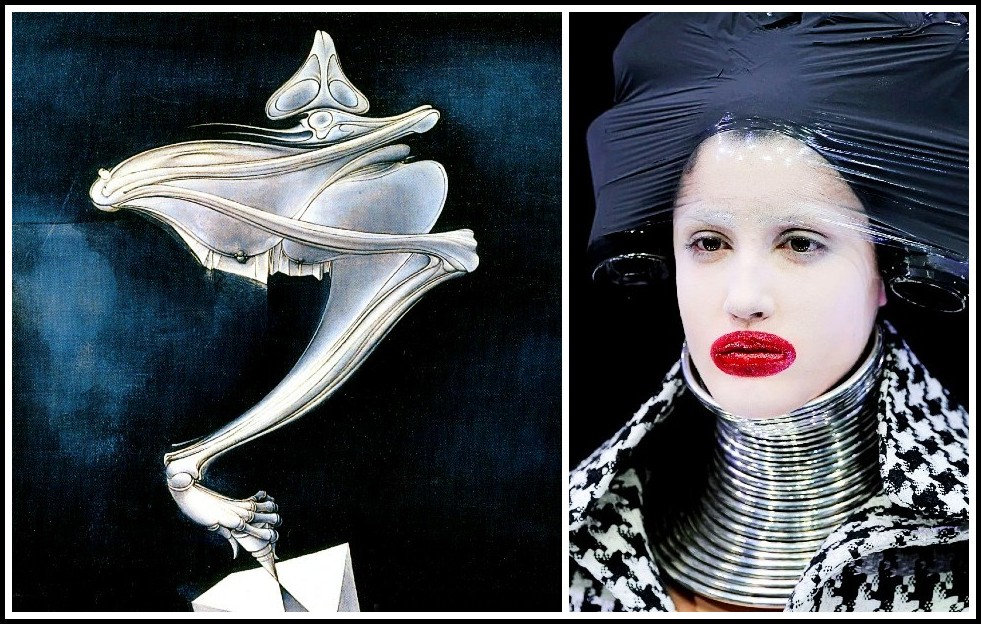

Hans Bellmer, La Toupie, 1952/56 | Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Vogue

It is in trying to answer this question that one can begin to take the full measure of McQueen’s accomplishment, and it is here that Jean Baudrillard’s concept of ‘fatal strategy’ proves to be a useful conceptual tool. Just what, then, is a ‘fatal strategy’? In various interviews*, Baudrillard defined it as follows:

Fatal strategy is not a discursive critique using negativity. Rather, it is an irony. It is a process of pushing a system or a concept or an argument to the extreme points where one pushes them over, where they tumble over their own logic. It’s a type of artifice using irony and humour. When you push a system to the extreme you see that there is nothing more to say. So there is a destabilization. A fatal strategy dismantles the order of irreversibility, it overturns the finality of things.

Fatal strategy is not really a strategy. That’s a play on words to dramatize the total passage from the subject to the object. In a fatal theory the object is always presumed to be cleverer, more cynical, and more inspired than the subject, whom it awaits ironically at the end of the detour. The fatal is the irony that lies at the bottom of the indifference of the objective processes to the subject’s desire for knowledge and power.

Ecstasy consecrates the end of a state through excess. There is no difference between the excess that represents the saturation of a system and that leads it to a final baroque death by overgrowth and the excess that stems from the fatal, from destiny. Today you can no longer find the dividing line between good and bad excess. We no longer know when we have reached the point of no return. That is precisely what makes the present situation original and interesting.

* Mike Gane, editor, Jean Baudrillard: Selected Interviews (Routledge, 1993 / Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003) 81, 37, 38, 39, 50, 57, 208. The three paragraphs here are my condensation and regrouping of relevant extracts.

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Models: Georgina Stojilkovic & Irina Kulikova | Vogue

McQueen’s artistic ambition across all his shows and collections is of the order of Baudrillard’s intellectual ambition. To interpret, for example, the fully-whitened faces and grossly-painted lips of The Horn of Plenty models as typically folle acting out (or simply as a homage to Leigh Bowery) is to greatly underestimate McQueen. The fact is that the designer, though he lived a full-blown homosexual lifestyle typical of his generation, never played the folle or camp card in his collections (in contrast to Galliano or Gautier, for example). The fact that he doesn’t settle for anything so easy should spur the fan, reviewer, or critic to raise their game. It is my contention that McQueen, in The Horn of Plenty, is doing everything Kate Bethune, in her article*, said he was doing—practicing subversion, operating in an ironic mode, parodying, making a political point, lampooning—but he was also doing something more ambitious. Indeed, in attacking the fashion business with its own weapons—drama, theatricality, exuberance; retrospective/re-invention; bigger, better, more; in pushing fashion’s own logic to the extreme—hyperconsumerism, excess, waste; ‘aggressive styling teetering on the precipice between the grotesque and the farcical’*—McQueen is demonstrating that ‘fascination’, in this case with the fashion presented in The Horn of Plenty, ‘is not dependent on meaning, but is proportional to the disaffection of meaning. It is obtained by neutralizing the message in favour of the medium’.**

* Kate Bethune, ‘The Horn of Plenty’ in ‘Encyclopedia of Collections’ in Claire Wilcox, editor, Alexander McQueen (London: V&A Publishing, 2015) 320

** Jean Baudrillard in Mike Gane, editor, Jean Baudrillard: Selected Interviews (Routledge, 1993 / Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003) 84

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Vogue

In The Horn of Plenty, then, McQueen, aware of the fact that in the fashion world—a world of hyperreality and hyperconsumerism—all the received modes of resistance are futile. So he is not ‘protesting against’ the massive mounds of waste generated by the fashion industry, he is not ‘making a case’ for eco-fashion; instead, he understands that, as Baudrillard puts it, ‘hyperreality is fundamentally a domain where you can no longer interrogate the reality or unreality, the truth or falsity, of something. We walk around in a megasphere where things no longer have a reality principle but rather a communication principle, a mediatizing principle’.* Of course, protesting against fashion-generated waste and arguing for sustainable fashion do indeed have an impact in ‘reality’. McQueen, were he alive today, would readily agree, but in his very next breath, I believe, he would make the point—in his own words, to be sure—that ‘the recuperative power of late capital is inexhaustible’ and that dame you saw yesterday in distressed jeans or a punk outfit from a luxury store is now parading the most stylish sustainable outfit bought from that same luxury store. In other words, he’d express his conviction that the desire that sustains fashion will always be captured by the hyperconsumerist machine, and that, as Baudrillard puts it, ‘one must abandon the objective radical position of the subject and of the message; one will have to work with the hyperreality of the system and enter the sphere of the floating signifier, of floating meaning or non-meaning, with risky strategies’.* To message and militancy McQueen preferred story and myth, to propaganda and ‘schools’ he preferred play and risk. He deployed ‘fatal strategies’, and it is this that contributed in large measure to making his work so distinctive.

* Jean Baudrillard in Mike Gane, editor, Jean Baudrillard: Selected Interviews (Routledge, 1993 / Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003) 146, 142

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Vogue

I conclude my reflections on The Horn of Plenty with three quotations from Baudrillard*. What do you think McQueen would have made of them?

Fashion is a splendid form of metamorphosis. It is both a ritual and a ceremony. It can’t be programmed.

Each person becomes the impresario of his own appearance, of his own artifice. There is here a new passion, ironic and new, that of beings devoid of all illusion about their own subjectivity. I would say almost without illusion about their own desires, all the more fascinated by their own metamorphosis.

Fashion is neither what is chic nor what is distinguished, it is a disenchanted mannerism in a world which no longer knows manners.

* Jean Baudrillard in Mike Gane, editor, Jean Baudrillard: Selected Interviews (Routledge, 1993 / Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003) 113, 41, 42

Alexander McQueen, The Horn of Plenty, A/W 2009 | Vogue

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—THE HORN OF PLENTY—COMPLETE SHOW

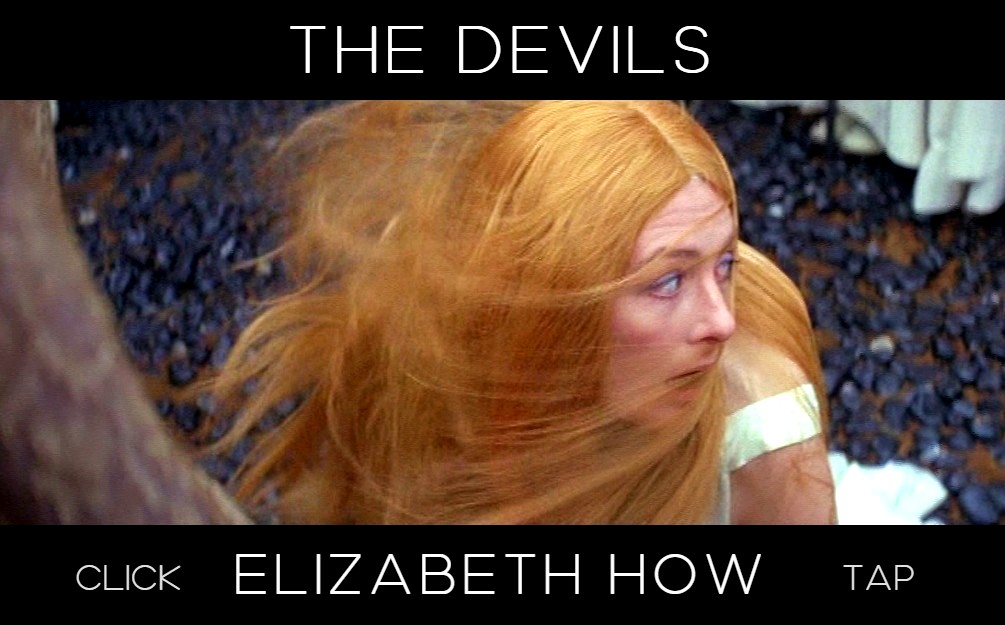

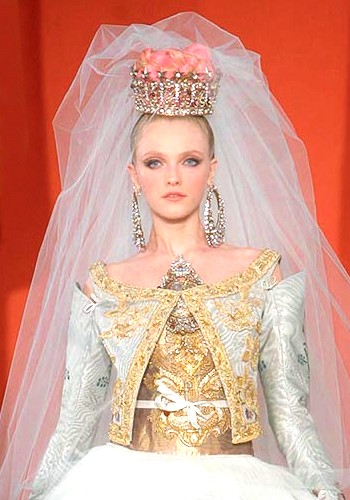

III. IN MEMORY OF ELIZABETH HOW, SALEM 1692 | A/W 2007-08

Le Zénith, Paris; 2 March 2007

Elizabeth How, convicted of being a witch, was hanged on 19 July 1692 in Salem, Massachusetts. Alexander McQueen, a day before his mother’s funeral on 11 February 2010, hanged himself in his flat in central London. Four years earlier, in Paris, McQueen had presented his collection In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692. Was the show an aesthetic compensation for the loss by judicial murder (the Salem witch trials) of his distant relative?

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

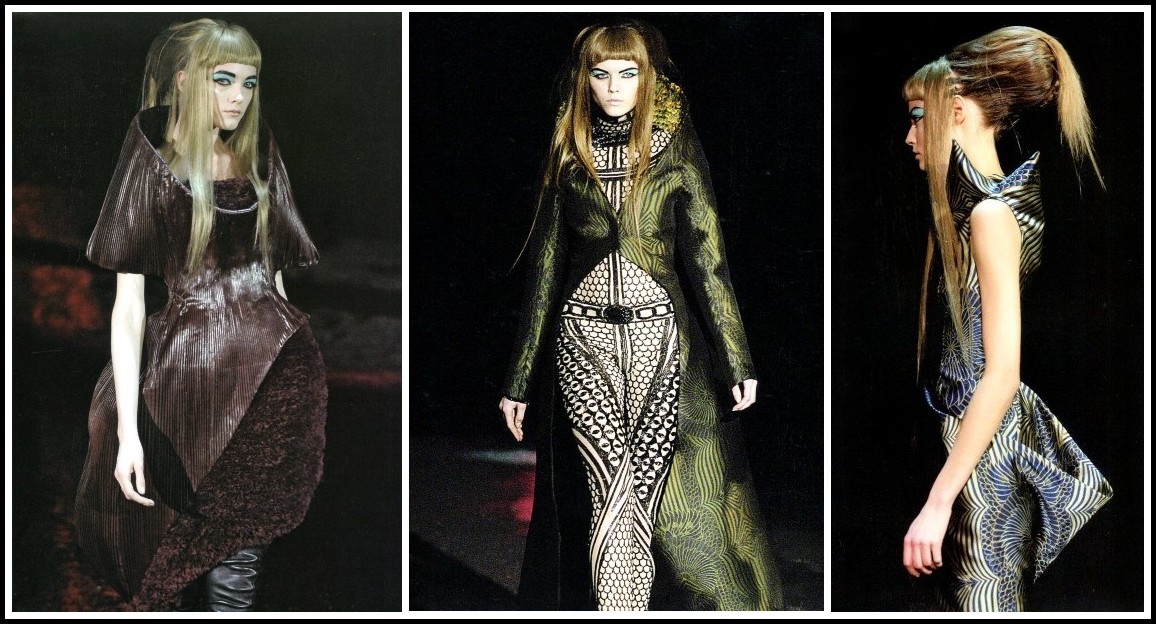

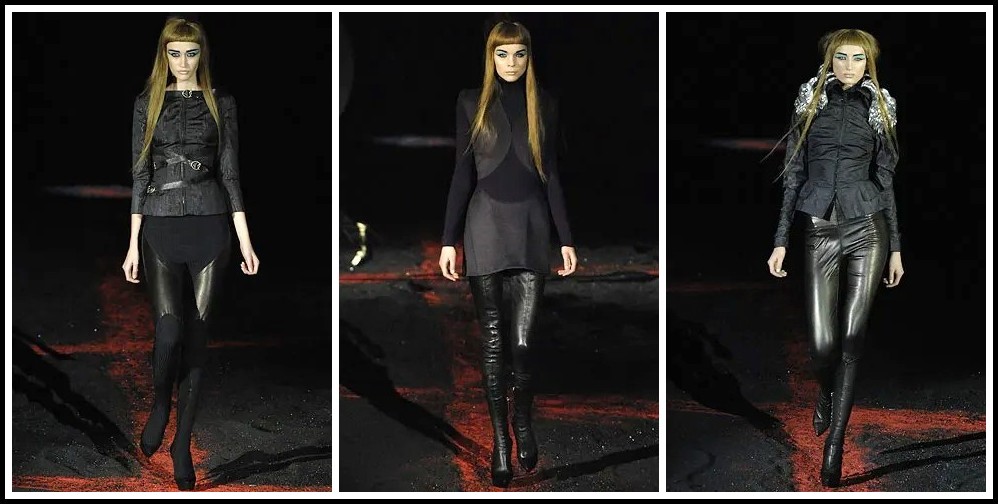

It would be quite a leap to imagine that a name on a genealogical tree stretching back more than three centuries could in any sense trigger ‘the work of mourning’. Blacks, dark browns and maroons, interspersed with iridescent blues and golds, constitute the show’s color palette. Could one interpret the movement between these two sets of colors as a movement from loss to consolation and back? A case could be made for that, but then one remembers, as Kate Bethune* reminds us, that iridescent blues and golds recall ‘the precious lapis lazuli and gold of Egyptian sarcophagi’. For McQueen, it would seem, the shadow of death, as presentiment or reminiscence, was never far away.

* Kate Bethune, ‘In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692’ in ‘Encyclopedia of Collections’ in Claire Wilcox, editor, Alexander McQueen (London: V&A Publishing, 2015) 318

The Crucible, Daniel Day-Lewis as John Proctor | Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692 | Joan Allen as Elizabeth Proctor, The Crucible, Arthur Miller/Nicholas Hytner, 1996

If not quite an elegy, then, if not quite a performance to fill a void, might In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692 be a protest against the carnage that comes upon the encounter of faith and ‘mauvaise foi’? I’d say not: there is no evidence of anger and indignation here. What then? I’d say the show and collection are simply one more McQueen celebration of the feminine. Yes, the fashion conveys the conviction that women enter with ease into communion with elemental forces, that women convey the vital current that draws together and unifies. Between living naturally and fathoming the divine, between expressing desire and aspiring to transcendence, women, McQueen seems to be saying, see no contradiction. To the extent that these qualities are embodied in the witch, then, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692 is, precisely, a celebration of the witch.

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692 | John William Waterhouse, The Magic Circle, 1886 (detail)

The red pentagram traced in black sand on the stage floor makes the affirmation of woman/witch explicit. The pentagram, besides being a symbol of knowledge, is also a means of casting spells and of obtaining power. Its symbolism is based on that of the number five; as such, it refers to fire, both the solar fire of triumphant day and the ‘Black Sun’ in its passage through the Underworld. In the show, we see both these aspects expressed in dress.

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

Many of the outfits, I find, convey a virile femininity; an effect reinforced by the models’ Cleopatra (Liz Taylor) makeup. Anyone who doubts the sexiness procured by a Luciferian edge need only look here to be convinced of it.

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

In In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692 we see, then, that once again, even when the theme is the judicial murder of a distant relative, McQueen refuses to portray women as victims. Instead, he presents a collection in which women calmly convey strength, self-confidence, and a sexiness that has no need of the come-on. In affirming the feminine, in celebrating the witch, McQueen is saying: ‘There are more things in heaven and earth than are dreamt of in your philosophy. My collection aims to adumbrate what those things might be.’

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

THREE ‘WITCH’ SONGS

In the three songs that follow, is it merely a coincidence that the one sung by a woman (Marianne Faithfull) presents a positive view of witches, while the two sung by men (Eric Clapton, Donovan) present a negative view?

WITCHES’ SONG

Marianne Faithfull

Shall I see you tonight, sister, bathed in magic greet?

Shall we meet on the hilltop where the two roads meet?

We will form the circle, hold our hands and chant

Let the great one know what it is we want

Danger is great joy, dark is bright as fire

Happy is our family, lonely is our ward

Sister, we are waiting on the rock and chain

Fly fast through the airwaves, meet with pride and truth

Danger is great joy, dark is bright as fire

Happy is our family, lonely is our ward

Father, we are waiting for you to appear

Do you feel the panic, can you see the fear?

Mother, we are waiting for you to give consent

If there’s to be a marriage, we need contempt

Danger is great joy, dark is bright as fire

Happy is our family, lonely is our ward

Da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da

Remember, death is far away and life is sweet

Da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da-da

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

STRANGE BREW

Cream

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

She’s a witch of trouble in electric blue

In her own mad mind she’s in love with you, with you

Now what you gonna do?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

She’s some kind of demon messing in the glue

If you don’t watch out it’ll stick to you, to you

What kind of fool are you?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

On a boat in the middle of a raging sea

She would make a scene for it all to be ignored

And wouldn’t you be bored?

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

Strange brew, strange brew, strange brew, strange brew

Strange brew, kill what’s inside of you

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

SEASON OF THE WITCH

Donovan

When I look out my window, many sights to see

And when I look in my window, so many different people to be

That it’s strange, so strange

You’ve got to pick up every stitch

Must be the season of the witch

When I look over my shoulder, what do you think I see?

Some other cat looking over his shoulder at me

And he’s strange, sure he’s strange

You’ve got to pick up every stitch

Beatniks out to make it rich

Oh no, must be the season of the witch

You’ve got to pick up every stitch

Two rabbits running in the ditch

Beatniks out to make it rich

Must be the season of the witch

Alexander McQueen, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem 1692, A/W 2007-08 | Vogue

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—IN MEMORY OF ELIZABETH HOW—COMPLETE SHOW

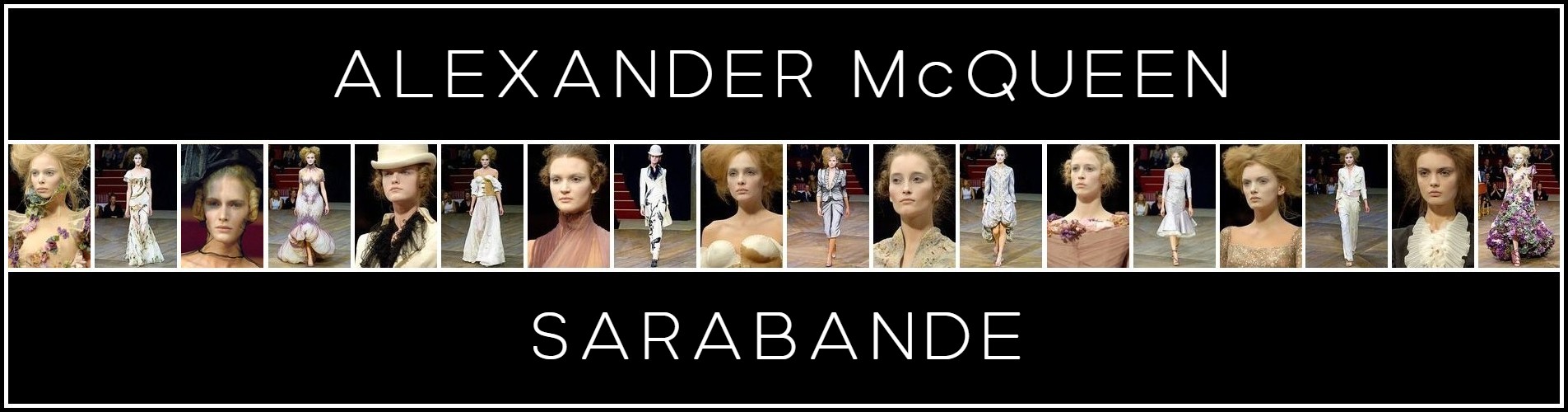

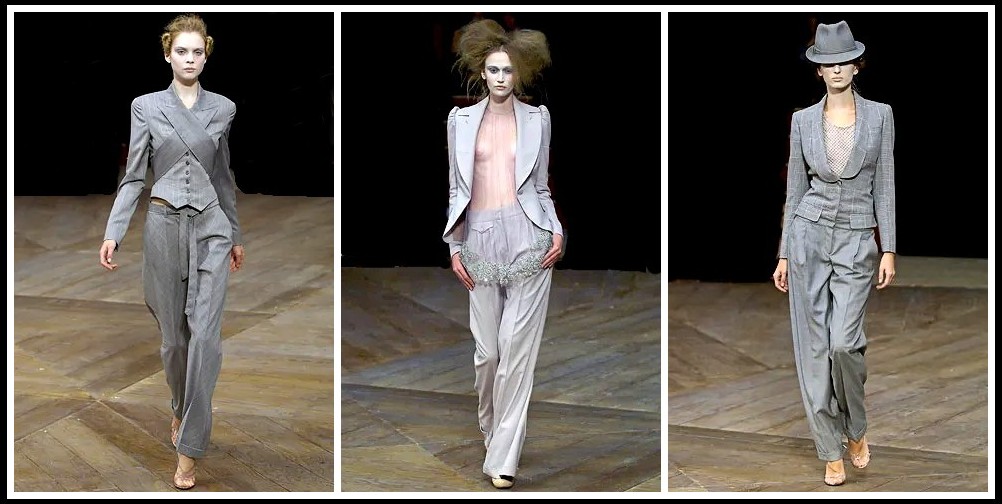

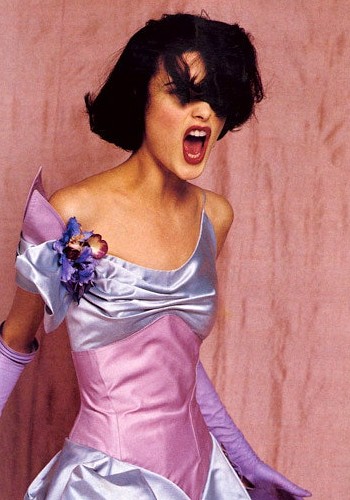

IV. SARABANDE | S/S 2007

Cirque d’Hiver, Paris; 6 October 2006

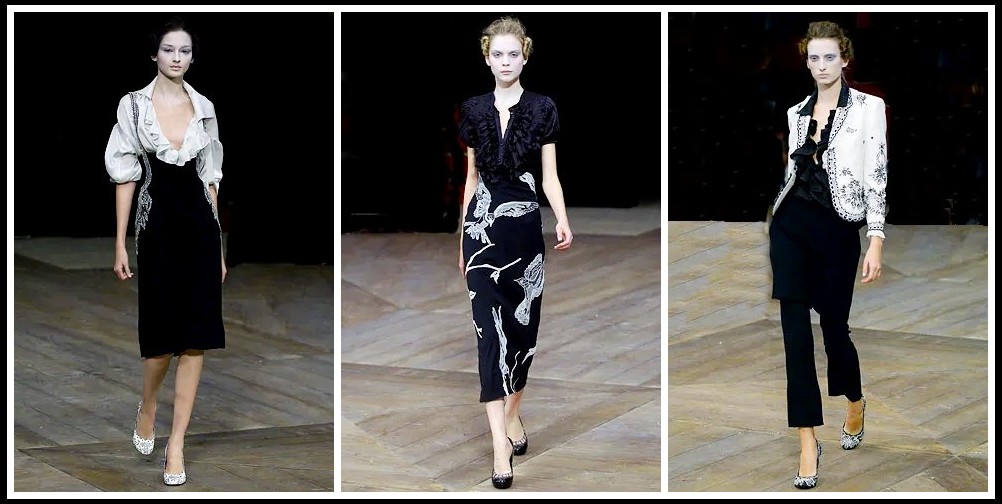

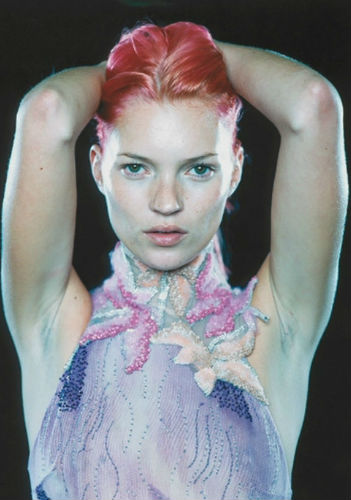

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007

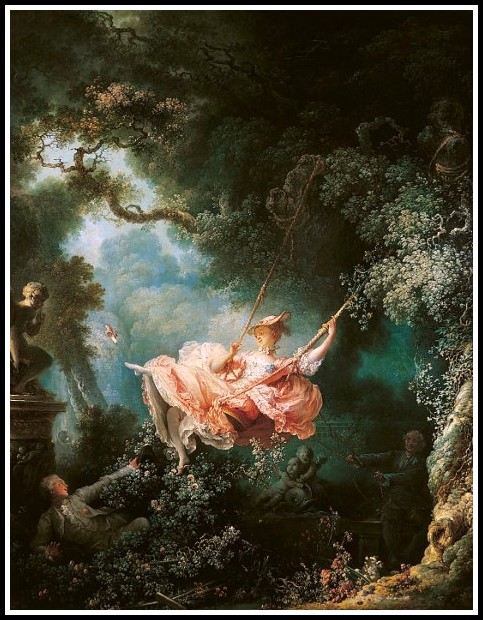

What was Alexander McQueen’s conception of nostalgia as far as it can be grasped in Sarabande? Once grasped, can it help us to gain a deeper appreciation of the show and the collection? I believe it can, and that is what I will attempt to do here. By way of establishing the theme of nostalgia, I offer my ekphrastic poem on Fragonard’s painting, The Swing (Les Hasards heureux de l’escarpolette).

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Vogue

FRAGONARD’S SWING

Richard Jonathan

Will he remember, when he’s old and grey,

How his heart would flutter to the sway of her swing?

Will she remember, when she’s past her day,

The kindling power of her petticoats?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

Toothless and dribbling, will he still recall

The arch of her instep, the sandal, the fall?

Her poise at the still-point between surrender and retreat,

Eyeless and infirm, will it still taste sweet?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

The thrill of expectation, the sudden glimpse—

Will they reminisce about their frivolity?

Will they be convinced by the instant’s eloquence

That to transience the flower owes its beauty?

Hearts like bells, celebrate the living

Mourn the dead, break the lightning

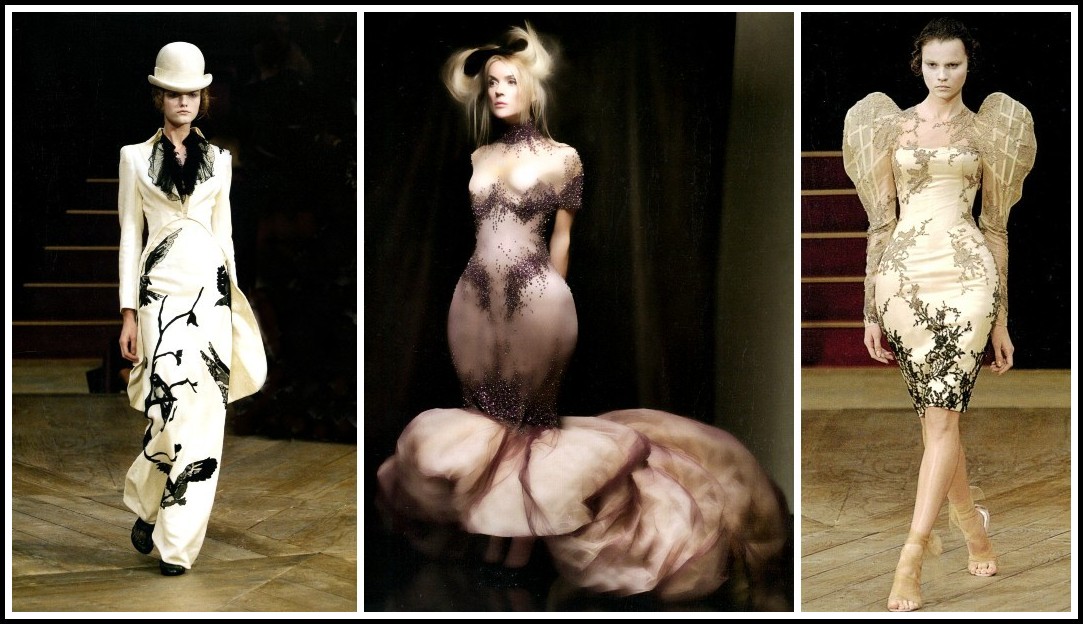

Jean Honoré Fragonard, The Swing, 1768

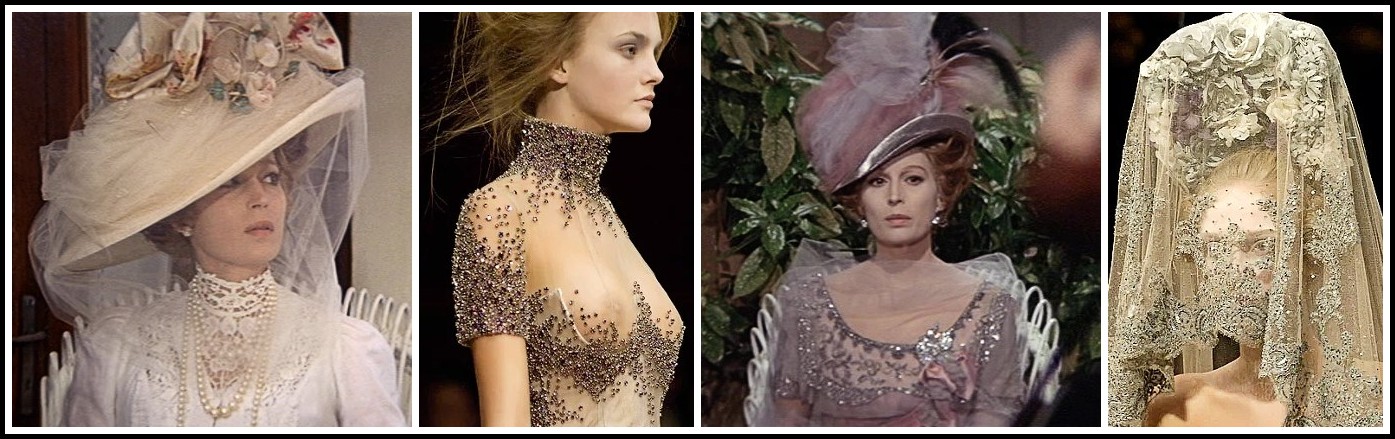

In one voice fashion writers hailed the tonality of Sarabande. Kate Bethune* described it as ‘fragile beauty undercut with a sense of decaying grandeur’ and ‘darkly romantic and quintessentially feminine’. McQueen, she found, ‘translated for his audience the beauty inherent in death and decay’. Judith Watt,** for her part, saw a predominance of ‘sensuality’ and a ‘sense of history’, while Katherine Gleason*** found Sarabande ‘romantic, nostalgic, even elegiac’ and ‘harking back to the turn-of-the-century Edwardian era, the last hurrah of the traditional aristocracy’.

* Kate Bethune, ‘Sarabande’ in ‘Encyclopedia of Collections’ in Claire Wilcox, editor, Alexander McQueen (London: V&A Publishing, 2015) 318

** Judith Watt, Alexander McQueen (Paris: Eyrolles, 2013) 171, 172 (I’ve back-translated the terms from the French)

*** Katherine Gleason, Alexander McQueen: Evolution (Race Point Publishing/The Book Shop, 2012) 155

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Silvana Mangano, Death in Venice, 1971

In these descriptions we find terms that point to the ‘edge’ McQueen gives nostalgia: ‘dark’, ‘decay’, ‘death’. I’d like to dwell on this, for doing so can, I believe, bring McQueen’s individuality into clearer focus. In his Harper’s Bazaar interview with Susannah Frankel in 2007, McQueen, speaking of Sarabande, said: ‘Things rot. It was all about decay. I used flowers because they die.’

FLOWERS DIE

The Only Ones

Cold days of winter have been and gone

Wonder what the summer will bring

Maybe a new love to carry me on

But first gotta get through spring

I don’t know why

But all the rivers

They’re gonna run dry

The first on, the last to go home

There’s a rustling behind me

Turn and look back but I should have known

There ain’t nothing to see

I find myself searching

For the real thing

I don’t know who I’ll be hurting

I came a long time ago

Been around since I don’t know when

Stuck it out even though I don’t fit

But I feel so helplessly alone, alone, alone, alone

I feel so alone

Come on and warm my heart, guitar

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Vogue

In the song ‘Flowers Die’, Peter Perrett sings, ‘I came a long time ago / Been around since I don’t know when / Stuck it out even though I don’t fit / But I feel so helplessly alone, alone, alone, alone’. In the same Harper’s Bazaar interview, McQueen says: ‘I came to terms with not fitting in a long time ago. I never really fitted in. I don’t want to fit in.’ And in an interview with Vice Magazine in 2002, he said: ‘I just use things that people want to hide in their head. Things about war, religion, sex, things that we all think about but don’t bring to the forefront. But I do, and I force them to watch it. And then they start saying it’s gross, and I’m like: “Actually love, you were already thinking about all this, so don’t lie to me”.’ Unlike with other designers who may display a ‘Gothic’ aesthetic, then, McQueen’s ‘aesthetics of decay’ is anything but an affectation. And when he declares ‘I don’t want to fit in’, this, too, is anything but a pose.

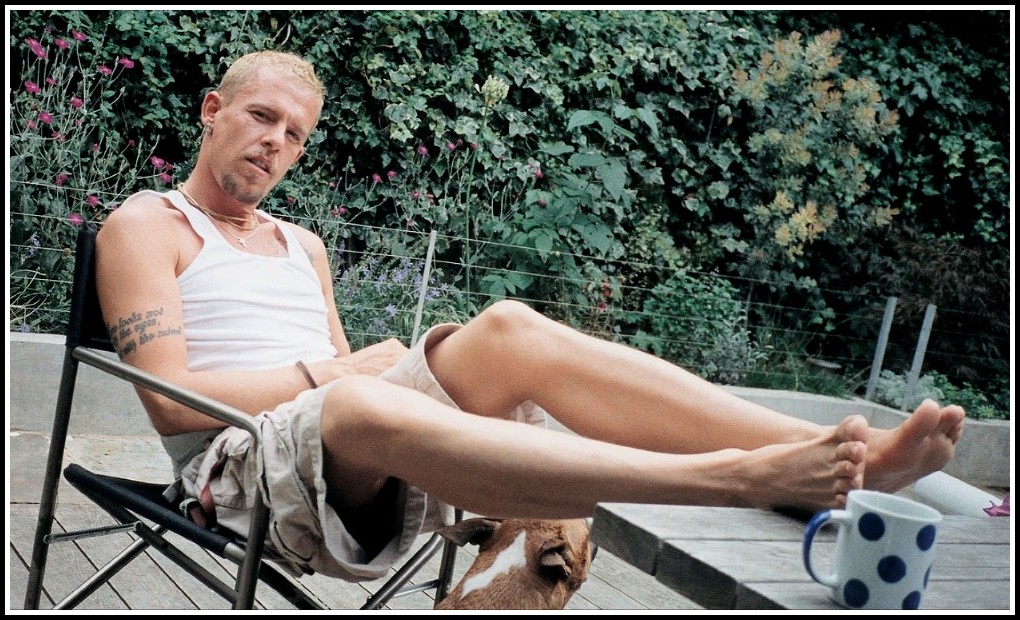

Alexander McQueen | Photo: Corrine Day, 2002

When designing the Sarabande collection, McQueen’s mood was ‘dark and romantic’.* The ‘romantic’, though tempered by the ‘dark’, prevailed. If to say the dark strain was dominant in McQueen’s sensibility** is to state the obvious, is there anything one can say about the ‘darkness that tempers the romantic’ in Sarabande that would not betray the shadow of his suicide ‘retro-projected’, as it were, onto this moment?

* Judith Watt, Alexander McQueen (Paris: Eyrolles, 2013) 171 (I’ve back-translated the terms from the French)

** McQueen followed up the lightness of Sarabande, we recall, with the darkness of ‘In Memory of Elizabeth How’. One can make an interesting parallel between McQueen and The Cure. Indeed, Robert Smith’s dark sensibility grounds the band’s very identity, and even in the gloriously joyous song ‘Just Like Heaven’, the beloved drowns in a ‘raging sea’.

Julia Margaret Cameron: Call I follow, I follow, let me die, 1867 | The Angel at the Tomb, 1870 | Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007

In Book V of The Joyful Science, we find a section (377) titled ‘The Homeless Ones’ in which Nietzsche writes a few lines that, by antithesis, may help develop my argument. ‘Nostalgia’, we recall, is a longing for, if not ‘home’, a feeling of being ‘at home’. Nietzsche writes:

Among the Europeans of today there are not lacking those who are entitled to call themselves homeless in a distinguished and honourable sense. We children of the future, how could we feel at home these days? We are offended by our era’s idealities, endorsement of which might make us feel at home in this fragile, fragmented, transitional period; and as for its ‘realities’, we do not think they will last. The ice which still supports us has worn quite thin; a thawing wind blows, and we ourselves, we homeless ones, are something which breaks the ice, and other all too thin ‘realities’. We are not ‘conservatives’ about anything, nor do we wish to return to some earlier age; we are by no means ‘liberal’, we do not strive for ‘progress’, we do not need to stop up our ears against the sirens of the marketplace who sing of the future – we are not in the least bit tempted by their songs.*

McQueen: ‘The shows always reflect where I am emotionally in my own life’ (Harper’s Bazaar interview). ‘My mind is too focused on my ideal and I can’t do that with somebody else’s collection’ (Vice Magazine interview). ‘I can only do it the way I do it. That’s why they [Givenchy] chose me, and if they can’t accept that, they’ll have to get someone else. They’re going to have no choice at the end of the day because I work to my own laws and requirements, not anyone else’s (Dazed interview). Indeed, McQueen always upheld his individuality; his struggle, unlike Nietzsche’s, was never with ‘our era’s idealities’ etc.: his struggle was always with himself (see the Voss section in Alexander McQueen: Feminine, Femininity, Feminist).

* Nietzsche, The Joyous Science (Penguin Classics, 2018) 283

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007

In Sarabande, then, McQueen may indeed be seeking refuge in the ineffable, eliding reason in the ‘elusive profundity’* of nostalgia, and stopping the world from turning to jump off into the past. Who doesn’t need to take a rest from themself once in a while?

* David Berry, On Nostalgia (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2020) 12

Marisa Berenson, Barry Lyndon, 1975 | Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007

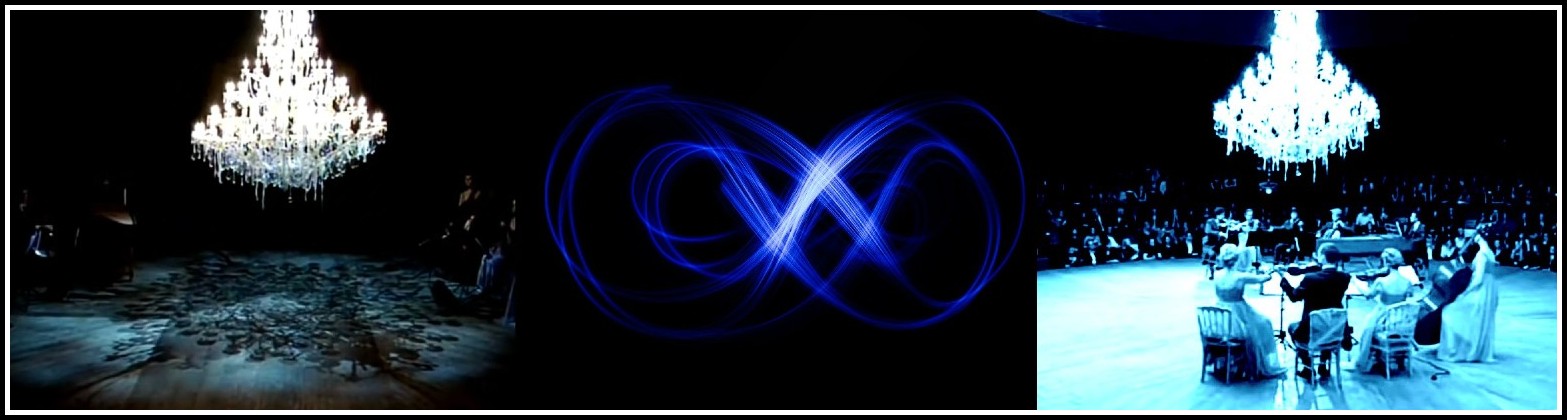

But McQueen’s nostalgia is not complacent, his self-soothing is not self-satisfied: as the models, one after the other, trace a figure 8 on the stage, they are figuring infinity as a timeless state, a state, I contend, that evokes death.

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Infinity symbol: Unsplash

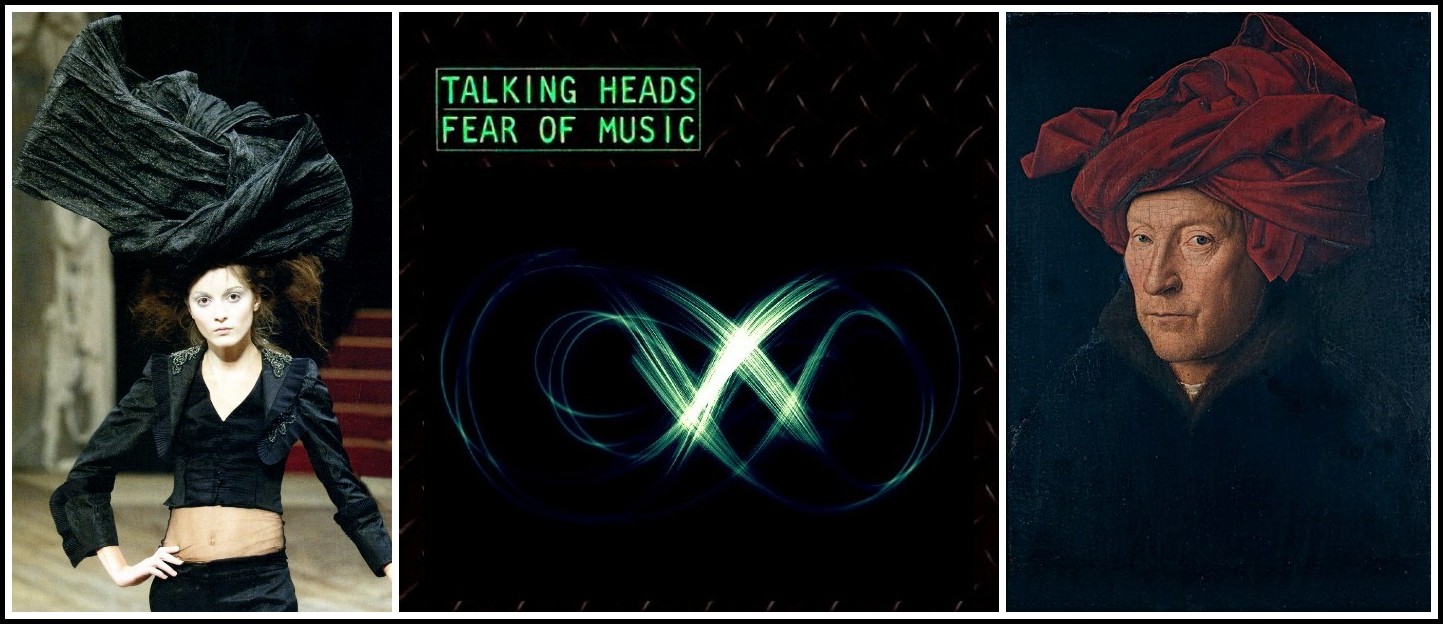

David Berry, via a discussion of the Talking Heads song ‘Heaven’, offers an acute analysis of this state:

In the song ‘Heaven,’ David Byrne sings about paradise as a place where nothing ever happens. Though it is not really nothing–it’s nothing new. The band here plays his favourite song over and over, at the same party, and it ends with a kiss that, when it ends, will start again, ‘will not be any different / will be exactly the same.’ I don’t believe there is much of anything after we die, but if there is anything like heaven, I am not sure how it could be anything but our greatest hits–maybe just our greatest hit–on infinite repeat. Everything else carries the potential for disappointment; we can’t know what we will like the most, only what we did like the most.

A sense of unease creeps into the lyrics as Byrne repeats, ‘It’s hard to imagine / That nothing at all / Could be so exciting / Could be this much fun.’ And of course the same perfect moment in perpetual loop is horrible: it’s death. Quite literally, if you believe in this kind of heaven, but obviously in the metaphorical sense, too. Nothing is so definitive until there is no more of it.

There is in ‘Heaven’ what I think of as the ultimate tension of nostalgia. It is a feeling that maybe feels too good, something that is so obviously appealing we can’t help but be a little wary of it. We know it is severely limited, ending exactly when the kiss ends, leaving out every part before and after that either made it meaningful or cracked the moment. And yet no amount of rational defence can prevent it from returning, nor feeling every bit as right as it did the last time.*

* David Berry, On Nostalgia (Toronto: Coach House Books, 2020) 7-8

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Talking Heads, Fear of Music, 1979* | Jan van Eyck, Self-Portrait, 1433

* I’ve added the infinity symbol to the album cover.

HEAVEN

Talking Heads

Everyone is trying to get to the bar

The name of the bar, the bar is called Heaven

The band in Heaven, they play my favorite song

They play it once again, they play it all night long

Heaven

Heaven is a place

A place where nothing

Nothing ever happens

There is a party, everyone is there

Everyone will leave at exactly the same time

It’s hard to imagine that nothing at all

Could be so exciting, could be so much fun

Heaven

Heaven is a place

A place where nothing

Nothing ever happens

When this kiss is over, it will start again

It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same

It’s hard to imagine that nothing at all

Could be so exciting, could be this much fun

Heaven

Heaven is a place

A place where nothing

Nothing ever happens

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Vogue

McQueen, then, as I see it, conceives of nostalgia as a state in which one may find consolation, but which turns deathly if one lingers in it too long. The genius of the Sarabande show is to have made this point through a seamless marriage of ‘form’ (the staging, the music) and ‘content’ (the clothes). Indeed, in staging the presentation of the outfits not in conventional linear fashion but in a flowing figure 8, McQueen makes it clear that, to all intents and purposes, the show could go on forever: ‘When this kiss is over, it will start again / It will not be any different, it will be exactly the same’. (Artists, we recall, make choices under resource constraints; whether a particular aesthetic effect is accident or intention is a moot point: all that counts is how the work actually ‘works’.)

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Audubon engravings, 1829 & 1827

Once we see this ‘infinity effect’, we gain a deeper appreciation of Sarabande, for we see that the subtlety of the dying flowers is reinforced by the ‘loop of death’. Indeed, we see that McQueen is staging a Gothic romance all the more magnificent for dispensing with skulls and crosses.

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Birgit Severin, Ashes, 2016

Fassbinder conceived of his films as different rooms in the same house: each different, yet each an element in a cohesive whole. McQueen is an artist in the Fassbinder tradition. Indeed, what he achieved in Sarabande is to have created a room that many took to be an annex to the main house when in fact it is integral to it. In other words, McQueen lets us believe in the romance, in the lightness of Sarabande, because he knows that the darkness that constitutes the core of his sensibility, like a scarab woven into an Oriental rug, is there for those with eyes to see it.

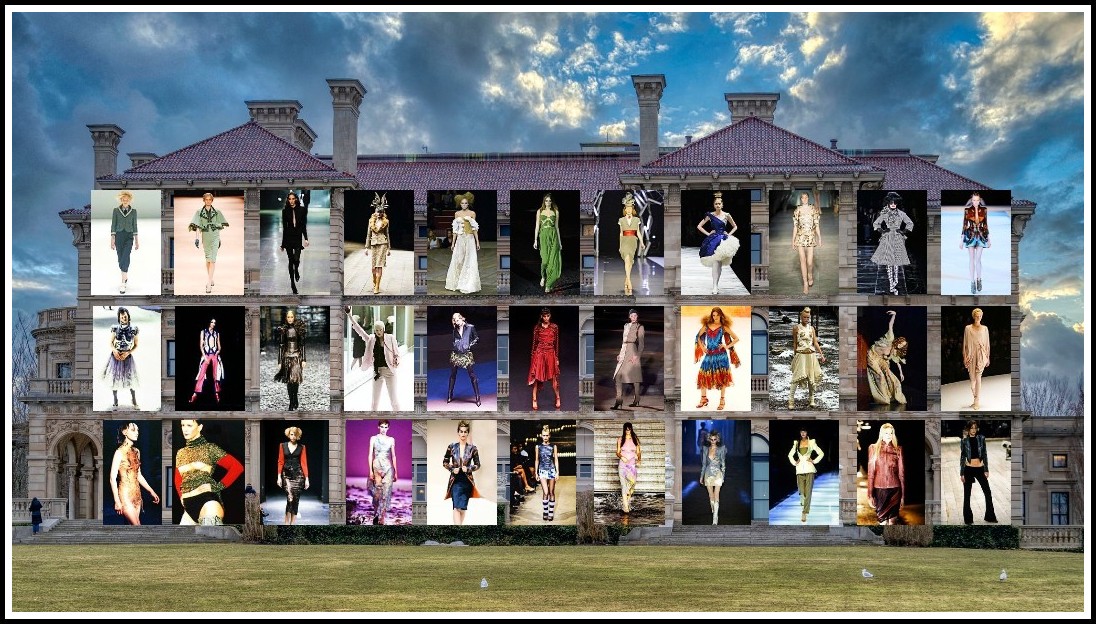

Alexander McQueen: 33 shows, 1 artistic sensibility: from Nihilism, S/S 1994 to Plato’s Atlantis, S/S 2010 | Underlying photo: Michael Denning, Unsplash

TWO ‘NOSTALGIA’ SONGS

As a conclusion to my discussion of Sarabande, I offer two Marianne Faithfull songs that present additional dimensions of nostalgia, each of which fruitfully illuminates aspects of McQueen’s show and collection.

BORED BY DREAMS

Marianne Faithfull

Things are never what they seem

Play a part most of the time

What is yours cannot be mine

And I’m bored by dreams

Bored by dreams

I can’t say the words I mean

Make myself go through the line

Does the payment fit the crime

If I’m bored by dreams?

Take me through the steps my love

Shall we dance again?

I was always older then

Now we are the same

Lasse des rêves

Rêves qui brillent dans le noir

Ira bien tu peux le croire

Toujours dire la vérité

Quand je suis lasse des rêves

Take me through the steps, my love

Shall we dance again?

Things were always brighter then

Hear me call your name

After a certain age every artist works with injury

Take me through the steps my love

Shall we dance again?

I was always older then

Now we are the same

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Vogue

YESTERDAYS

Marianne Faithfull

Yesterdays, yesterdays

Days I knew as happy sweet

Sequestered days

Olden days, golden days

Days of mad romance and love

Then gay youth was mine

Truth was mine

Joyous free and flaming life

Then truth was mine

Sad am I, glad am I

For today I’m dreaming of

Yesterday

Alexander McQueen, Sarabande, S/S 2007 | Vogue

V. CODA – ALEXANDER McQUEEN: GOING HOME

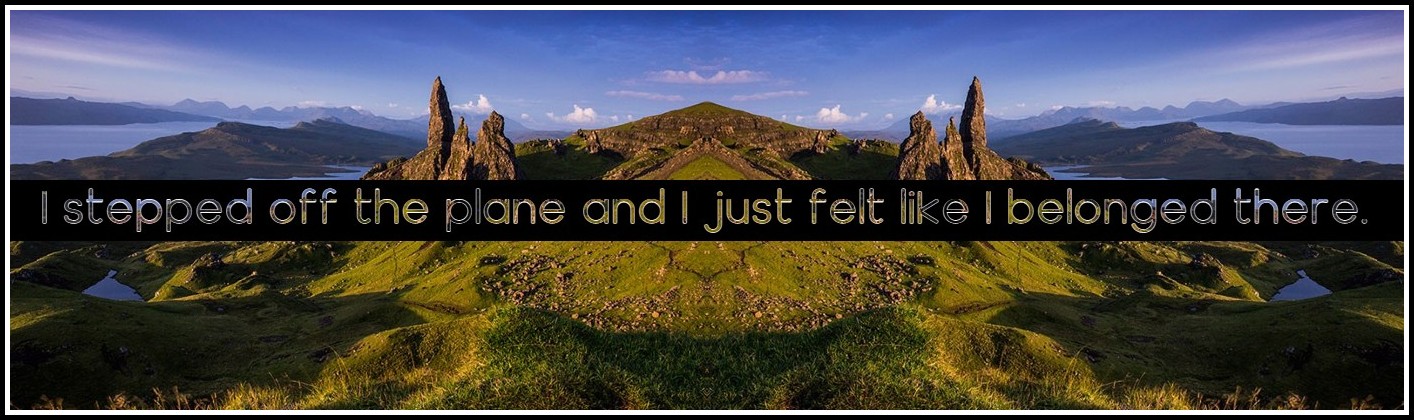

Storr, Isle of Skye (Scotland) | Photo (mirrored): Marcus MacAdam

‘I like London, but I love Scotland. I’d never been to Aberdeen before and I went to see friends in Aberdeen for the first time and it was unreal because I stepped off the plane and I just felt like I belonged there. It’s very rare that I do that because I have been to most places in the world, like most capital cities in Japan and America, and you feel very hostile when you step off the plane in these places. I stepped off the plane in Aberdeen and I felt like I’ve lived there all my life. And it’s a really weird sensation. I like more of the Highlands. My family originated from Skye.’ Alexander McQueen interview, Dazed & Confused, 1996.

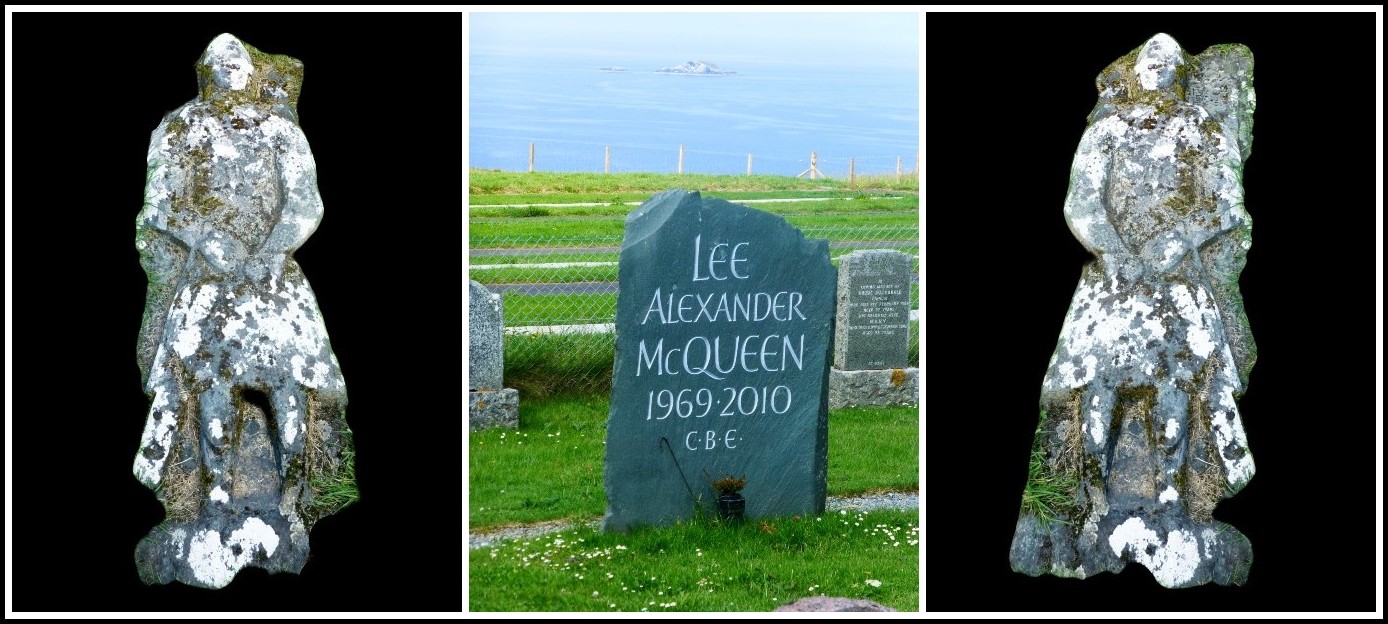

Headstone marking the scattered ashes of Alexander McQueen | Grave Marker of Angus Martin | Kilmuir Graveyard, Isle of Skye | Photos: Françoise Richard

ALEXANDER McQUEEN—SARABANDE—COMPLETE SHOW

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

FASHION IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments