I. INTRODUCTION | II. HEDDA GABLER: TRAGEDY VS. MELODRAMA – A CRITIQUE OF FOUR PRODUCTIONS (1963-1975)

HEDDA GABLER, IBSEN’S GLORIOUS CREATURE

PART III – HEDDA GABLER: TRAGEDY VS. MELODRAMA – A CRITIQUE OF FOUR PRODUCTIONS (1963-1975)

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

Max Beckmann, Quappi in a Pink Sweater, 1935

I. INTRODUCTION

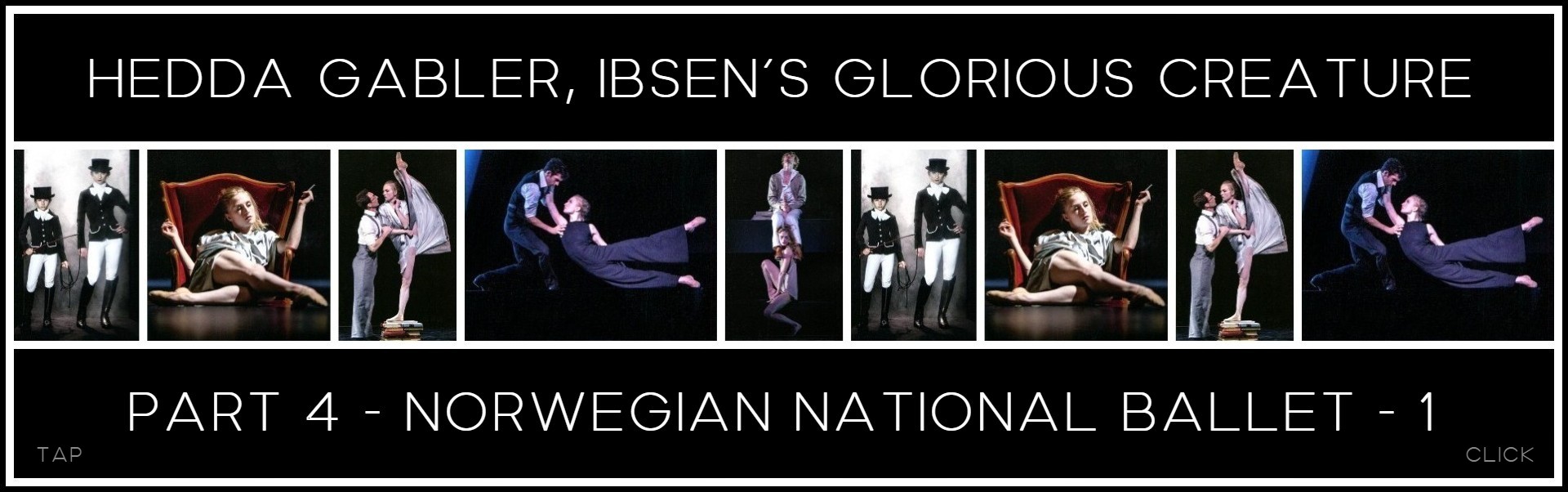

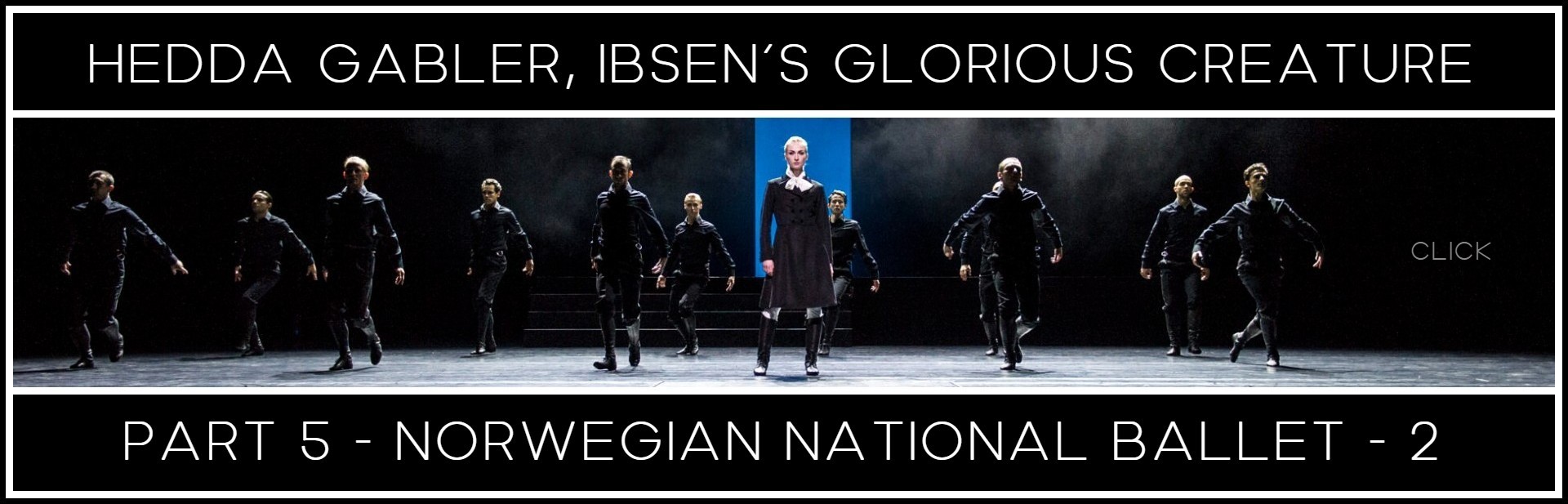

This essay, the third in a series of four, continues my study of why many productions of Hedda Gabler fail to deliver the excitement Hedda’s capacity to fascinate1 deserves. The play’s mise-en-scène remains my focus as I address the challenge of staging a classic work today. I will demonstrate, in posts 4 and 5, how the Norwegian National Ballet’s production of Hedda Gabler rises above all the rest, delivering a Hedda who unfailingly fascinates and in doing so, renders all the richness of Ibsen’s drama. The four productions I will examine here are currently available via streaming. I list them below by director, company, actress playing Hedda, year of production, and availability.

1 – Trevor Nunn | Royal Shakespeare Company (London) | Glenda Jackson | 1975 | youtube

2 – Waris Hussein | BBC | Janet Suzman | 1972 | youtube

3 – Raymond Rouleau | France Télévision | Delphine Seyrig | 1967 | Amazon Prime (in French)

4 – Alex Segal | Paramount-BBC-CBS | Ingrid Bergman | 1963 | youtube

1 – See Part 1, Hedda Gabler: Psychosexual Dynamics

Edvard Munch, Hedda Gabler, 1907

II-A. HEDDA GABLER: TREVOR NUNN | RSC | 1975

Glenda Jackson is not a convincing Hedda Gabler, and it’s Trevor Nunn’s direction that’s to blame for this failure. He got the dramaturgy right—the concision of his filmmaking brings out Ibsen’s dramatic lines with great clarity—but his conception of Hedda is all wrong. In this film version of his stage production she comes across as a shrew who needs taming, but as Tesman is no Petruchio her shrewishness becomes a drone that drowns out all other notes in her character. One-note Hedda, far from fascinating us, bores us. The director did nothing to get his actress off this monorail to nowhere; when her suicide comes, we simply don’t care. As I have no way of knowing what’s behind this directorial failure, I will focus on what we can all see: Glenda Jackson’s acting.

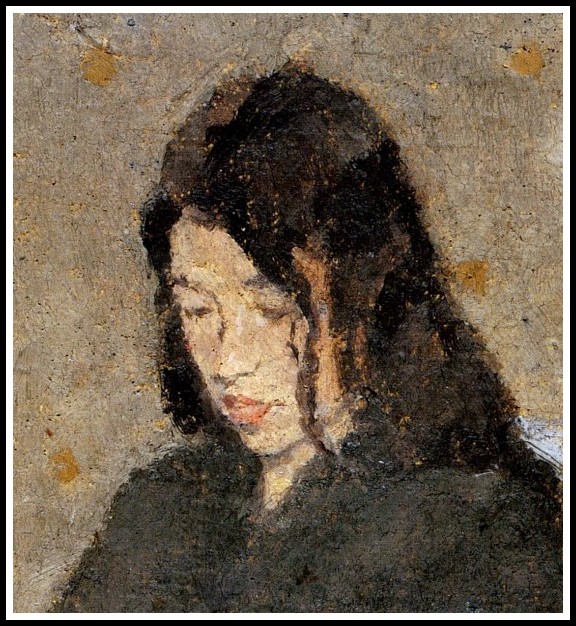

Gwen John, Young Woman Holding a Rosary, 1920 (detail)

Aged thirty-nine when she made the film, Glenda Jackson was too old to play Hedda: all dressed up and nowhere to go, incessantly bitching and self-pitying, is a state unbecoming to a mature woman. With Brack she trades her customary sneer for a complicit smile, yet she’s too stewed in her own bile to convey any inkling of her desire. We simply have no idea what makes her tick, what she’s like when nobody’s looking. She’s obviously sexually stuck up—she never ‘jumps’ for fear a man might ‘see her legs’; she tells Løvborg ‘there’ll be no unfaithfulness’ when her husband is already a stranger to her bed—but what exactly is her hang-up? Does she know the difference between orgasm and jouissance, is she as afraid of one as of the other? Or is she more pedestrian, refusing to give any man the pleasure of giving her pleasure? We simply don’t know, because the way Glenda Jackson plays Hedda Gabler denies us any access to her interiority. Indeed, Glenda makes Hedda a glib wise-cracker, using words as armor against ghosts from her subconscious.

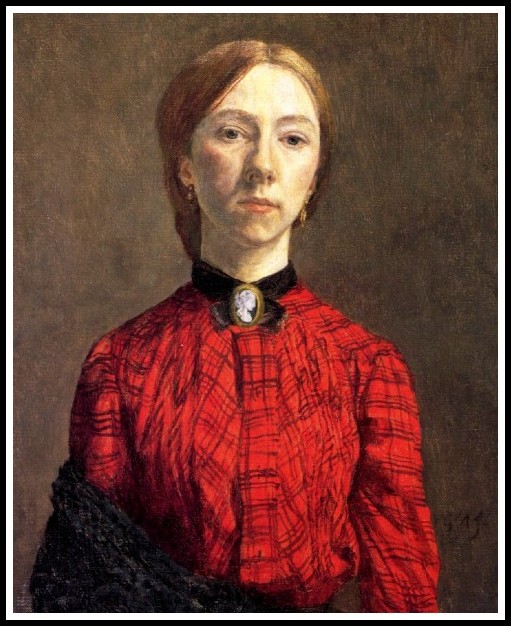

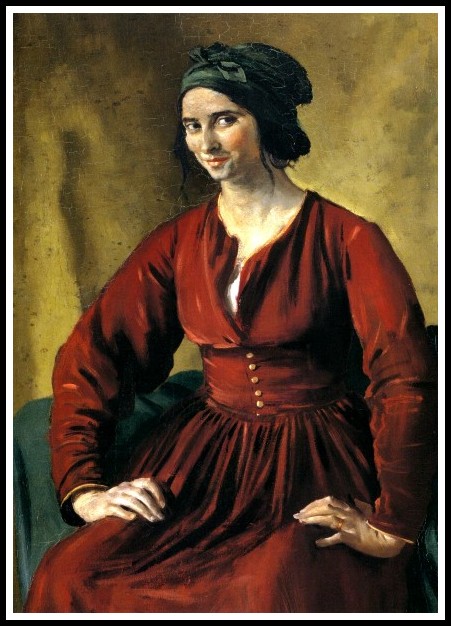

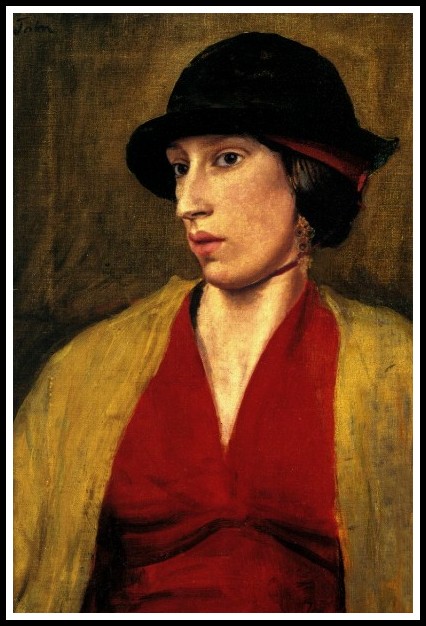

Gwen John, Self-Portrait in a Red Blouse, 1902

We need to see cracks in that armor for Hedda to emerge through it; that we don’t is, I am arguing, a failure of mise-en-scène. Glenda never makes Hedda vulnerable enough for us to care about her. Her coldness comes across as calculated meanness, not as a coping mechanism. (I dare not use the term ‘frigidity’, because ‘frigidity’, in contrast to the imagined vaginas of the female subjects so identified, is a remarkably slippery concept.1) In her conversations with Brack, for instance, Hedda’s easy repartee gives no hint of her inner turmoil. The one scene that does work in this respect is when Brack tells Hedda that Løvborg shot himself ‘in the pit of the stomach’. Here Glenda, going further than Ibsen’s stage direction (‘looks up at him with an expression of disgust’), has Hedda put her hand over her mouth as she chokes and retches: the physical displaces the cerebral, the truth of the flesh confounds the subterfuges of speech, the body reclaims what the word usurped.2 But speech abandons subterfuge when Hedda cries out ‘Grotesque farce!’, ‘Squalid charade!’: she realizes she rules over an empire of nothing. For Hedda to be more than a shrew, the director, I am arguing, should have had the actress complement—and even replace—speech with physicality far more often. A missed opportunity in this regard is, for example, the scene where Hedda burns Løvborg’s manuscript: it would have been far more effective if Glenda Jackson had used her body instead of her voice to express her transgressive elation at burning Løvborg and Thea’s ‘child’. As it is—and not only in this scene but throughout the play—by limiting the actress’s physicality to her mouth—the cut-glass articulation of the syllables of sarcasm, the twisting of the lips into a sneer—the director distances us from Hedda and drains her of the fuel3 that feeds her fire: she loses all capacity to fascinate and excite.

1 – Alison Moore & Peter Cryle, ‘Frigidity at the Fin de Siècle in France: A Slippery and Capacious Concept’ in Journal of the History of Sexuality, Volume 19, Number 2, May 2010, p. 243

2 – Isabelle Adjani, as far as I know, never played Hedda. More’s the pity, as she is, in my view, the greatest actress of physicality, of showing thought and emotion through the body. See my series on Film Actress & Global Classics in the Mara Marietta Culture Blog.

3 – Hedda’s ‘fuel’ is, of course, her psychosexual dynamics, the forces in her subconscious.

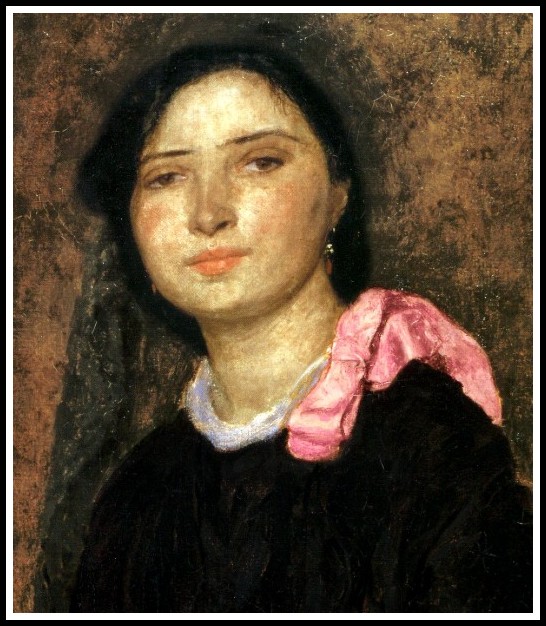

Gwen John, Dorelia in a Black Dress, 1904 (detail)

Another consequence of the way Glenda plays Hedda is that many of her lines no longer ring true or have the effect that Ibsen intended. The same goes, to some extent, for the dramatic situation itself. We feel, for example, that Glenda’s worldly-wise Hedda would never have gotten herself trapped in such a marriage in the first place. Recognizing that she has, we then consider that a woman so cynical would never sacrifice herself to such an extent merely for the sake of social propriety. As for the romance implicit in Hedda’s vision of Løvborg crowned in vine leaves, it is undermined by the fact that Glenda never ever reveals Hedda’s romantic inclination. As Peter Hall, Trevor Nunn’s then-colleague at the RSC, put it, ‘Glenda’s Hedda was glum from the word go, bent on a course of self-destruction’.1 And when Hedda, explaining the hat incident to Brack, says, ‘I get a sudden urge. I can’t explain it’, we are not convinced: Glenda never allows Hedda a respite from self-control, not a moment of spontaneity.

1 –Peter Hall & John Goodwin, Peter Hall’s Diaries: The Story of a Dramatic Battle (Oberon Books, 2016) p. 176

Gwen John, Seated Girl Holding a Piece of Sewing, 1920 (detail)

More generally, we observe that the director, by bringing the actress’ voice to the fore in his mise-en-scène—highlighting her delivery, accentuating her repartee—makes it hard for us to imagine that Hedda has anything in her that’s beyond the reach of words. In thus reducing Hedda to her verbal expression, in undermining the intuition that she has reserves of silence in which her struggles play out, he gives us a Hedda who cannot fascinate and excite. Indeed, if we do not feel that Hedda has forces within her that are greater than what she can verbalize, she cannot be Hedda Gabler.

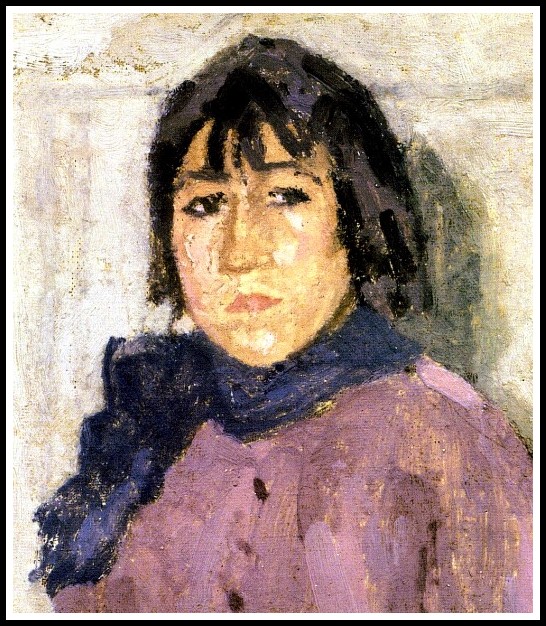

Gwen John, Girl with a Blue Scarf, 1923 (detail)

As a consequence, the undertow of sexuality that drives Hedda is ignored in the mise-en-scène. Hedda, I contend, wants nothing more than for a man to conquer her,1 that she may at last experience the jouissance that would make her life something other than the ‘grotesque farce’ and ‘squalid charade’ that she feels it is: she needs (but doesn’t know she wants) someone to make her ‘real’ (not ‘grotesque’, not ‘farcical’). There is no such character in the play, but the production could hint at Hedda’s desire for one by having her speak more from the body than from the brain. This would then be reinforced by a mise-en-scène in which, at key dramatic moments, word and image would be in disjuncture: only through a crack can the light get in. In short, for Hedda to be Hedda Gabler, the weight of the unspoken must match the weight of speech.

1 – See Part 1, Hedda Gabler: Psychosexual Dynamics

Gwen John, The Convalescent, late 1910s (detail)

Glenda Jackson is a great actress who excelled at conveying Hedda’s surface: that aspect of the role played to her strengths. To convey Hedda’s depths, however, she would have needed a director able to get more out of her than ‘off-the-shelf’ Glenda Jackson. Could it be that it is precisely her qualities that made her ‘not a natural’ for the role? Indeed, she conveys a very English matter-of-factness that ill-serves Ibsen’s text, a text in which it is precisely what is not ‘matter-of-fact’—the intangibles that fall ‘between the lines’—that drive the drama. Indeed, if the cynicism and irony that come naturally to the actress give her cutting remarks more bite, they produce the opposite effect when it comes to conveying Hedda’s underlying vulnerability. Without that vulnerability, as I’ve argued, Hedda loses what makes her appealing: her complexity, the contradictions in her character. In refusing to go for a Hedda both frigid and fragile, both sexless and sexy, the director turns her into nothing more than a luckless avenger against a lousy fate. ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’ is nowhere to be seen. Pity.

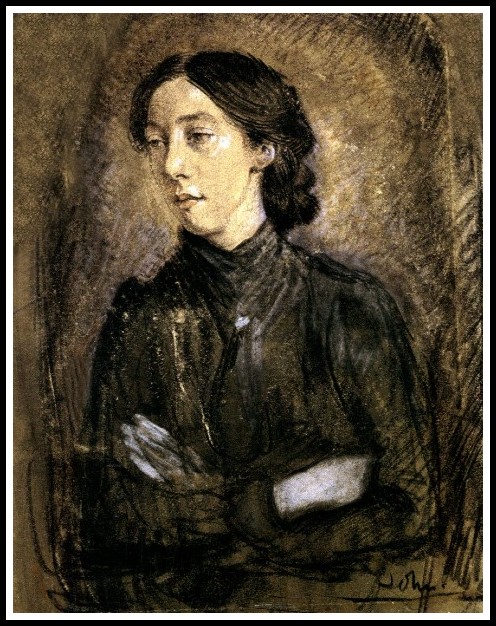

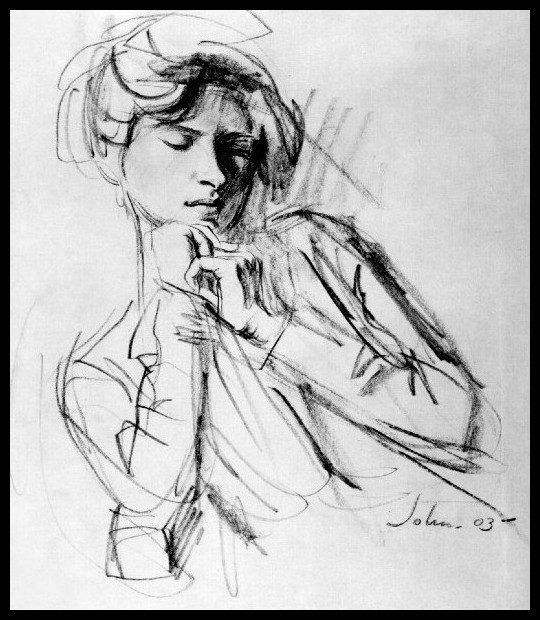

Augustus John, Study for a Portrait of Gwen John, 1901

II-B. HEDDA GABLER: WARIS HUSSEIN | BBC | 1972

Janet Suzman is both a fine actress and a perceptive analyst of acting and drama. As Hedda in this production she gives an accomplished performance, and as a participant in a colloquium she delivered an excellent paper on ‘Hedda Gabler: the Play in Performance’.1 My thesis here is this: Despite her excellence as both actress and analyst, Janet plays Hedda wrong: she takes the Gabler out of Hedda. This is all the more surprising since, in her talk, she demonstrates a remarkable lucidity:

Hedda will not stand definition. Some nights, true to form, she eluded me as she will elude others. But that’s her secret strength. She knew she could not be defined, the devil, and in the end she triumphs in that evasion. The free spirit roams in Hades.

The other people are the antidote to her own vibrancy, except for one. That one is Eilert. The others hem her in, disgust her, bore her, annoy her, desolate her. They are the prose to Eilert’s poetry. And to poetry—compressions, metaphors, mysteries—she responds.

In Janet’s understanding of Hedda (‘Hedda will not stand definition’ ‘she triumphs in that evasion’, ‘to poetry—compressions, metaphors, mysteries—she responds’) there is nothing I do not share: it is with the physical expression of that understanding, it’s translation via acting, that I find fault. Perfectly attuned to Hedda’s genius2 on the page, Janet may have captured it on stage, but in this TV production she fails to do so3.

1 – Janet Suzman, ‘Hedda Gabler: the Play in Performance’ in Errol Durbach, editor, Ibsen and the Theatre: The Dramatist in Production (New York University Press, 1980) pp. 83-104. Republished, with revisions, in Janet Suzman, Not Hamlet: Meditations on the Frail Position of Women in Drama (London: Oberon Books, 2012). All Janet Suzman citations are from this source.

2 – By ‘genius’ I mean ‘that in Hedda’s character that makes her Hedda Gabler’, that ensemble of forces that fascinates and excites.

3 – She herself says: ‘I played Hedda for the television, and it was a pretty good production all in all. But the thing that is infuriating about that medium, with a difficult play like this one, is that no sooner do you get a glimpse of what other paths open up to you as you hasten round the maze of her character, than the game is over. The thing is recorded. Done. Finished. I came away from that knowing I had a long way to go.’ Keep in mind that in terms of interpretation (both of the role and the play) it is the director who is ultimately responsible.

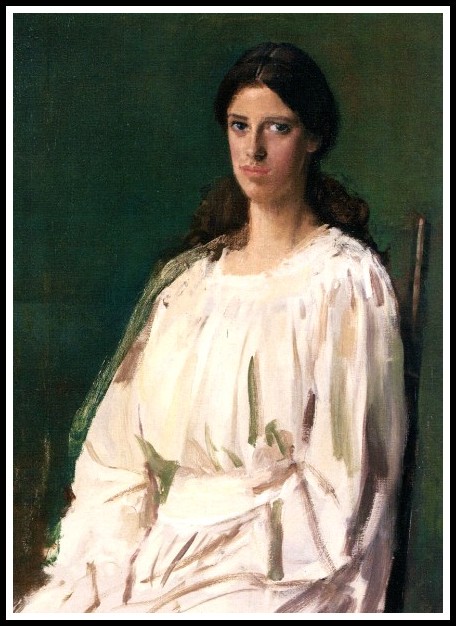

Augustus John, Woman Smiling, 1909

If many a great actress has had a go at Hedda and come up short, the reasons why may well be found here:

The dark burlesque of the manuscript/child, the fact that Tesman’s cobbled-together mediocrity will not translate Løvborg’s inspirational thought, is a metonym for Ibsen’s own text, which cannot hope to translate Hedda. Hedda, too, is an unreadable text. In his preparatory notes Ibsen announces, ‘The play shall deal with the impossible’.1

When he comes to write Hedda Gabler, Ibsen is far from suggesting that any effort of the understanding or resolution of the will can rescue his heroine from the sinister power of the paternal influence. For that reason the presence of General Gabler and the sense of corruption associated with it must be pervasive, yet no more than suggestive in its implications. Ibsen wishes not to identify a problem and delineate its solution but to evoke a condition and to let us know, by symbolic implication, that it is immutable. He does not want us to see Hedda as the victim of her father’s misconduct; rather, he wants us to sense that her aspirations are tainted at the very roots. For all his psychological prescience Ibsen is here concerned, not to analyze a relationship, but to create a symbol.2

The challenge for the actress, then, is how to ‘play the impossible’, ‘evoke a condition’, ‘create a symbol’, given that, as Janet Suzman points out, ‘You cannot act concepts or abstractions or theories. What Ibsen meant I see only on the page of the text’. Readers of Hedda Gabler create the character in their imagination, and Ibsen’s text suffices to make Hedda fascinating. Actresses playing her on stage/screen find she often escapes them, and in a bid to pin her down make her pedestrian: cynical bitch, sacrificial victim, imprisoned bride, lost child—whatever the spin, the actress reveals Hedda’s delirium, but not her desire. (May I remind you, dear reader, that ‘desire’ is not what you want, but what, unbeknown to you, ‘makes you tick’.) The overriding challenge in playing Hedda, then, is to show her desire: not what she wants, but what drives her.

1 – Elin Diamond, Unmasking Mimesis: Essays on Feminism and Theatre (Routledge, 1997) p. 26

2 – Arthur Ganz, ‘Miracle and Vine Leaves: An Ibsen Play Rewrought’ (PMLA, Vol. 94, No. 1, Jan. 1979), p. 17

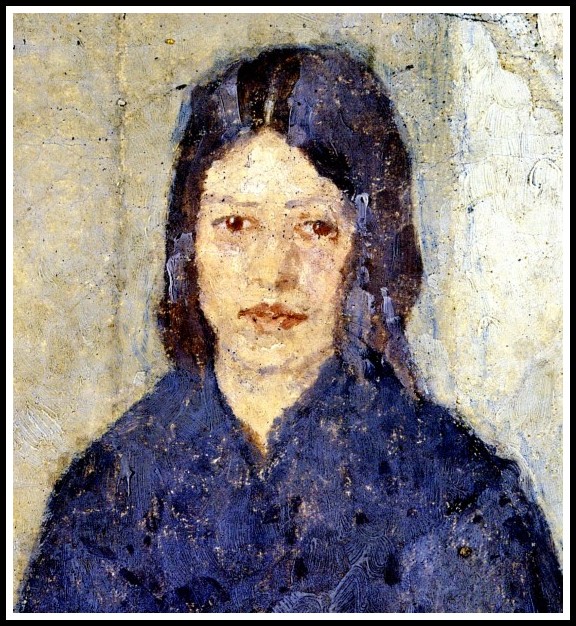

Gwen John, Self-Portrait, 1900

My argument can now be restated more precisely: Janet Suzman shows what Hedda wants (it’s all in the text) but not what she desires (it’s all between the lines). Her performance is finely crafted; she pays great attention to detail in both voice and gesture. For example, in both her assertions and her responses she measures out the emotional charge with great precision, giving a rounded view of the dynamics at work in the dialogue. Given her observation that ‘from the actor’s point of view, realistic drama is not all that realistic; Hedda is no less out of the ordinary than Cleopatra’, it is all the more to her credit that her acting comes across as natural and fluid. And therein lies the problem. Given that the production adopts a set of stale naturalistic conventions, to play Hedda naturalistically is to make her, too, seem musty. This is compounded by the fact that Janet’s wholesome aura is incompatible with Hedda’s diabolical streak. When she acts bitchy she appears apologetic; even in her rudeness there’s a reserve of politeness. More serious than this mismatch, however, is the impression she conveys of having to ‘justify’ every word and gesture. As a consequence, her acting, while ‘natural’, comes across as cerebral: she can’t seem to let herself go. Given her understanding of the character, it is surprising that Janet, in striving to show the ‘logic’ of Hedda’s behaviour, doesn’t realize that in ‘rationalizing’ her actions she is ‘normalizing’ her—exactly the opposite of her stated aim: to preserve Hedda’s mystery.

Augustus John, Mrs. Randolph Schwabe (Birdie), 1916

As I tried to demonstrate in the first essay in this series, ‘Hedda Gabler: Psychosexual Dynamics’, Hedda’s desire is to be sought in her struggle to come to terms with sexual difference and femininity. Janet Suzman writes: ‘Never forget that when Eilert Løvborg enters the room for the first time, Hedda stays silent for nigh on five minutes. Is that a woman totally in command of herself? I think her knees have gone wobbly. I think her heart is racing for the first time in five years.’ In the film, the director does capture Hedda’s raptured stare as she gazes upon Løvborg. Given this, we assume that the role of sexuality in Hedda’s desire was understood by both actress and director. So why is it so played down in the film? ‘No sex please, we’re British’ and ‘BBC 1972’ are obvious answers, made more so when we remember I Am Curious (Yellow/Blue) had found a wide audience five years before. It is equally obvious, however, that developing an artistic discourse on sex (beyond monologues and performance pieces) is no less a challenge than developing a mutually-satisfying one in a couple. If sex, outside scientific discourse, is not amenable to discursiveness, in the mytho-poetic domain of art it shouldn’t be problematic, right? The fact is that there is something in sex that is unassimilable to any discourse, and the vast majority of audiences (and audience-obsessed ‘artists’) refuse to have anything to do with it. In the case of Hedda Gabler this is a major handicap, since to ignore Hedda’s psychosexual dynamics and struggle with femininity is to reduce her to just another melodramatic character.

Augustus John, Miss Pettigrew, 1900

The play opens with Hedda and Tesman’s return from their honeymoon. ‘Heavy in the air is the matter of what is happening in their sexual relationship.’1 Not much, it quickly becomes clear. We soon recognize, however, that at some point during those six months Hedda, engaged in a conflict between female power and male sexuality, submitted, at the expense of her self-esteem, to male sexuality.2 How did it happen, we wonder? Did Hedda arouse herself by imagining Løvborg fucking Diana? (To arouse herself, ‘fucking’ would indeed be her preferred word.) Did Tesman, medieval scholar, conjure his hand up the extravagant green dress of ‘The Magdalen Reading’ in order to get a hard-on? Did they do it in the dark? Did Tesman ever stop talking? Did Hedda at least see, if not touch, the instrument of his ardour? Did she admit she wants to be ravaged and regret that Tesman was not up to the task? If the actress playing Hedda ran such thoughts through her mind from time to time, would that not give her performance the edginess it would otherwise lack? And if she could express through her body Hedda’s confusion of phantasies of violence with sexual desire, would that not make her a more realistic (as opposed to ‘realist’) Hedda? That Janet Suzman, under Waris Hussein’s direction, does not do these things explains in large measure why her Hedda is not ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’. Pity.

1 – Margaret Rustin & Michael Rustin, Mirror to Nature: Drama, Psychoanalysis and Society (London: Routledge, 2019) chapter 6

2 – K. M. Newton, Modern Literature and the Tragic (Edinburgh University Press, 2008)

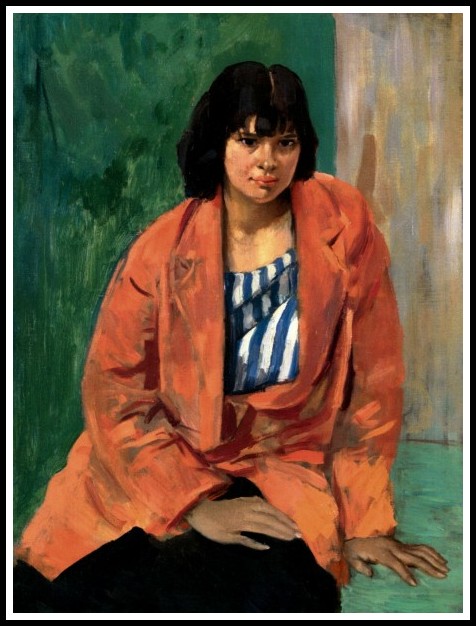

Augustus John, The Orange Jacket, 1915

II-C. HEDDA GABLER : RAYMOND ROULEAU | FRANCE TÉLÉVISION | 1967

Delphine Seyrig’s performance in this television production is the finest portrayal of Hedda Gabler of the eight studied in parts 1 and 2 of this series. She creates a Hedda who fascinates, despite the fact that other elements of the film do not measure up to her performance. How does she achieve this? That’s what I’ll now examine. Here’s my thesis: In the domain of culture, every innovator suffers a degree of debasement by his or her acolytes, and this has been Ibsen’s fate. A return to the original, then, may produce exciting results. That is precisely what Delphine Seyrig does as Hedda Gabler: she reinvigorates ‘Ibsenian acting’, freeing it of the mannerisms that marked its decay. Her acting is as light as the imprint of wind on a puddle of water, and as deep as the disturbances in still water’s depths.

Augustus John, Dorelia Asleep, 1903

Every innovative work of art teaches the recipient its aesthetic. So, in theatre, we learn that Pinter makes the pause a hieroglyph, Genet makes a mirror of play-acting, and Ibsen restores verticality to time. G.G. Cima, in ‘Ibsen and the Critical Actor’, articulates ‘Ibsenian acting’ in these terms:1

In Ibsen’s dramas the characters are conscious of ‘the irony of things’. Hedda is often fully aware of the ridiculousness of her situation, and can even joke caustically about it. She is capable of self-dramatization, of creating a role for herself different from the role she has been assigned. Consequently, the actress who portrays her must play a double action while also being aware of her own self: a treble consciousness is required.

The task of the Ibsen actress is to reveal the simultaneity of the melodramatic and the ‘real’, to reveal the two lines of action simultaneously, both Hedda’s motivation within her private melodrama and her action in the realistic play of which she is a part.

Given his structural method of retrospective action, Ibsen requires another kind of double motivation as the actor reveals the character’s past actions through present ones. To clarify this conflation of past and present action, the actress portraying Hedda, for example, has to show the audience a glimpse of the electricity that drew her to Lövborg in the past as she ‘play-acts’ the album scene with him in the present.

With the advent of Ibsen’s plays and their individualized characters, a revised category of gesture became necessary: the autistic gesture, or subtle visual sign of the character’s soliloquy with him/herself (subtle facial expressions, especially eye and lip movements; movement of the hands in relation to the body). This type of introspective gesture allowed the Ibsen actor to reveal the dialogue taking place within the character and the various lines of action it implied.

With the autistic gesture Ibsen actors revealed the role the character thinks she is playing as well as the role she is actually playing. They opened a gap through which the audience could see the actor mediate the character’s performance of conflicting roles. As a consequence, taking Hedda Gabler as an example, we see that the actress’ creation of Hedda’s awareness of the absurdity of the role she plays constitutes a new subversive lever in the theatre. Her suicide may be played in such a way as to affirm her comic stance, her contention that life, as she is being asked to act it as a woman, is ridiculous. The actress and the audience can see this fact and are therefore able to apprehend the implications of the conventional solution, the woman’s suicide. Hedda simultaneously mocks and enacts the role of woman as ideal victim.

1 – Compiled and edited for the sake of concision from Gay Gibson Cima, Performing Women: Female Characters, Male Playwrights, and the Modern Stage (Cornell University Press, 1993) pp. 20-59.

Augustus John, Dorelia, 1907-1910

To the interviewer’s surprise that she had studied with Lee Strasberg at the Actor’s Studio in the late 1950s, Delphine Seyrig responded: ‘That’s because one confuses style with the famous Method. What I learned at the Actor’s Studio is a method. Strasberg taught us to draw on our own lives, not only on our experience but also on our dreams—which is also part of our lives. Of course there is the realist style that one identifies with the Method, but style is what one adds to reality, it is the form.’1 There is no element in Delphine Seyrig’s acting in Hedda Gabler that other actors don’t commonly use. So what makes her performance so distinguished? It is this: She employs all the aspects of ‘Ibsenian acting’ outlined above and gives them the coherence of ‘significant form’;2 it is this that elevates her performance out of the ordinary. Transposing Clive Bell’s definition from the visual arts to acting, we can define ‘significant form’ as ‘voice and gesture combined in an aesthetically moving way, certain forms and relations of forms of body/voice that stir our aesthetic emotions’. Two elements in particular make Delphine Seyrig’s acting in Hedda Gabler supreme: her use of autistic gesture (‘subtle visual signs of the character’s soliloquy with herself’) and her use of voice (sound/silence, soft/loud/, slow/fast).

1 –‘Entretien avec Delphine Seyrig – Vertige du jeu’ in Michel Beauchamp et Marie-Claude Loiselle, 24 images, Numéro 44-45, automne 1989. Translated here from the French by Richard Jonathan.

2 – Clive Bell, ‘The Aesthetic Hypothesis’ in Francis Frascina & Charles Harrison, editors, Modern Art and Modernism: A Critical Anthology (London: Routledge, 2019) pp. 67-74

Augustus John, Dorelia, 1907-1910

Delphine Seyrig’s voice has the captivating timbre of a viola: though capable of being mournfully passionate, she generally employs it dispassionately, unmodulated, letting its characteristic huskiness works its magic. Pitching her vocal performance at the opposite extreme of the hysterical, she delivers her lines softly, evenly, not exactly slow but a little behind the beat,1 as it were. The effect is striking, and is perfectly suited to ‘Ibsenian acting’. Take the scene where Tesman ask Hedda to call Miss Tesman ‘Auntie Ju’, now that his wife is ‘part of the family’. Delphine Seyrig, seated at the piano, doodling a tune, softly says, ‘Oh, the family…’, and closes the piano, not slamming down the lid but letting it fall shut. She then remains still in the resonance of the bang. There is no hint of violence, sarcasm, or bitterness in her voice, but the full weight of the phrase ‘part of the family’ comes through in all its implications.

1 – Like Helen Merrill sings.

Augustus John: Ida, 1906 | Dorelia (Forza e Amore), 1907-1910

One gesture Seyrig employs to great effect is that of looking into space, absorbed in the ‘verticality of time’ that ‘Ibsenian acting’ demands. Here, she precisely positions the angle of her gaze (about halfway between the camera and her interlocutor) and the tilt of her head (just a touch downward), conveying a mind in turmoil while the body remains static: rarely has introspection be rendered so effectively. The examples are multiple; I’ll mention but three. First, the scene where Hedda learns from Thea that Løvborg is back in town, that his book is a success, and that Thea has left her husband. At each of these ‘high-key verbal events’, Delphine Seyrig conveys in a low key just how much Hedda is moved (surprised, troubled, frustrated, regretful). Second, in the album scene with Løvborg, filmed in close-ups that forgive no acting error, the disjunction between Hedda’s voice and her gestures (one in the present, the other in the past, then the other way around, then back again) conveys very convincingly the tension between both Hedda and Løvborg and Hedda and herself. Here, Seyrig’s ‘looking into space’, her ‘interior gaze’, renders all Hedda’s shifting ambiguity. Third, when Tesman tells Hedda he has Løvborg’s manuscript, and later when Løvborg tells Hedda he wants to ‘put an end to it all’, Seyrig’s use of this ‘autistic gesture’ of looking into space is so persuasive that it feels to us like an internal monologue or soliloquy: we ‘hear’ Hedda’s mind ticking, we ‘see’ her thinking.

Augustus John: Dorelia, 1907-1910

Delphine Seyrig’s performance, as I’ve tried to demonstrate, is characterized by an understatement that enhances its effectiveness. It is free of the mannerisms that mark the decayed naturalism of lazy ‘Ibsenian acting’ (conformity to type, stock rhetorical devices, suppression of contradiction). If Seyrig, like every thinking actor, calculates the effect she wants to produce, her excellence lies in her ability to confer on calculation an air of spontaneity. Never gratuitous, the repertoire of body/voice gestures she employs are always prompted by the dynamics of the drama. Furthermore, they are inscribed in a coherent interpretation of Hedda Gabler, character and play, and they constitute a style, style being, as Seyrig said, ‘what one adds to reality, the form’. And, thanks to her collaboration with the other actors and the director, that form is ‘significant form’ because, inscribed in a whole that is greater than the sum of its parts, it is aesthetically moving. ‘As light as the imprint of wind on a puddle of water, as deep as the disturbances in still water’s depths’: Delphine Seyrig, in reinvigorating ‘Ibsenian acting’, delivers a Hedda who, for once, is indeed ‘Ibsen’s glorious creature’: she fascinates and excites.

Augustus John, Dorelia, 1907-1910

II-D. HEDDA GABLER: ALEX SEGAL | PARAMOUNT-BBC-CBS | 1963

Ingrid Bergman’s Hedda Gabler, in this television production of the play, singularly fails to fascinate. Why is this Hedda so far from Ibsen’s heroine? The explanation is threefold. First, playing a young married couple embarking on an independent life, both Ingrid Bergman (48) and Michael Redgrave (55) are far too old for their roles. Moreover, Løvborg, the driver of the drama, is played by a 50-year-old actor (Trevor Howard) who is conspicuously in his sunset years, while Ralph Richardson as Brack, coming across as much older than his 61 years, is unable to convey the intelligence and cynicism, that wit and charm, the role requires. Second, both the adaptation of the dialogue and the mise-en-scène are dumbed down for a television audience presumed to be dimwits. Finally, the production, largely because of the reasons already given, is unable to uphold the tragic dimension of Hedda Gabler. As a result, it becomes nothing more than a melodrama, and fails to measure up to what Ibsen had in mind. We will now elaborate (but not belabor) each of these explanations in turn.

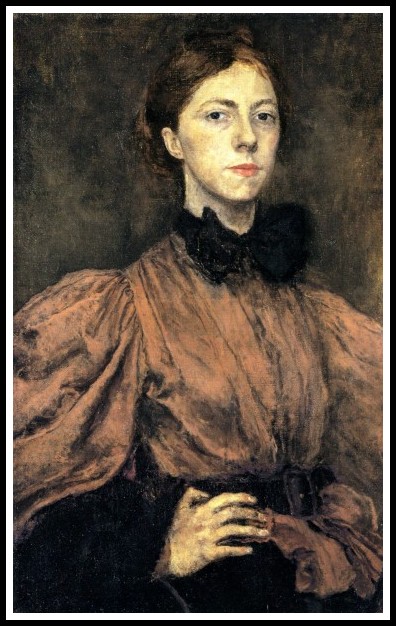

Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, Self-Portrait in Profile, 1801

First, let’s look at the age problem. What are its consequences? Its immediate effect is to undermine the entire subtext of the play—which, of course, is where the dramatic action finds its source. With not only Tesman but also Løvborg and Brack coming across as sexless, Bergman, even if old enough to be Hedda’s mother, loses whatever opportunity she might have had to radiate sex appeal. As a result, the primary subtext of the play—Hedda’s struggle to come to terms with sexual difference and femininity—can never be drawn on in the dramatic action. Bergman gives us no hint of Hedda’s autoeroticism, her secret sexual pleasure,1 dwelling instead on sex’s reproductive function. Indeed, she repeatedly plays up Hedda’s pregnancy, tightening her robe or crossing her arms over her belly at every opportunity the text gives her. She never conveys Hedda’s boredom and frustration with the same conviction as she communicates her panic and anxiety at her pregnancy. The upshot of ‘baby’ outweighing ‘husband and house’ (in the formula of female entrapment) is that Hedda comes across as a petulant, spoilt child rather than as what she is: an adult enmeshed in the toils of sex, staging a drama (Løvborg’s ‘suicide’) that is but a symptom of her struggle with herself.

1 – See Part 1, Hedda Gabler: Psychosexual Dynamics

Vigée le Brun, La Baronne de Crussol Forensac, 1785 (detail)

Another consequence of the age problem is ridiculousness. Although not as important as the effacement of sex, it no less undermines Hedda’s capacity to fascinate. Indeed, ridiculousness and fascination are incompatible. And so we have a Tesman awaiting his first post at an age when retirement would normally be on the horizon; a Hedda too old to conceive panic-struck at the prospect of a first baby; a Brack so dull and pedantic that it’s unimaginable he could keep up his corner of the ‘triangle’, and finally, a Løvborg far more convincing as a conventional drunk than as an intellectual rebel who happens to please women.

Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, Madame du Barry, 1781

Second, let’s consider the dumbing down of both the dialogue and the mise-en-scène. How does it contribute to making Hedda ordinary? Let’s have a look. The writer and director were at pains to remove the asperities of Ibsen’s play. A few examples: They tried to make Hedda ‘nicer’ by having her always refer to her husband as George, not Tesman; they had her peruse Løvborg’s manuscript (‘what a decent person would do’) and not simply ignore his writing (as Ibsen wrote); and they had Hedda, on first meeting Løvborg again, not hint in any way that she is stirred (‘good girls don’t show any interest in sex’). More seriously, the writer and director, taking the audience to be dumb, remove ambiguity. For example, at Brack’s party, they show Brack repeatedly filling Løvborg’s glass, thus making Løvborg not responsible for himself (‘Brack’s to blame’). Later in the play they have Tesman say, ‘I called on Løvborg to tell him his manuscript was safe, but he wasn’t home’, thus removing any ambiguity about Tesman’s behavior (‘secretly he still wants Løvborg out of the way’).

Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, Léonie de Rivière, 1831

More generally, often where Ibsen suggests something, the writer has the actor spell it out. For example, where Ibsen has Thea unable to look Løvborg in the eye, let alone speak to him, because she is panic-struck at his having found out she doesn’t trust him, the writer has her excuse herself to Løvborg (and not simply say to Hedda and Tesman, as Ibsen wrote), ‘It’s just that [you] were alone in the city, with no-one…’. Similarly, writer and director always prefer word to gesture, the discursive to the mythic, because their aesthetic doesn’t allow them to use the expressive power of the body. For example, when Tesman tells Hedda that Løvborg’s book will be ‘one of the greatest ever written’, and adds, ‘Just think of that, Hedda’, Bergman, instead of showing through gesture that Hedda is jealous of Thea, says (in a wink to the audience that she is hatching a plot), ‘I am thinking’ (rather than saying what Ibsen wrote: ‘Yes, yes, that’s of no interest to me’). In short, there where Ibsen shows, this production tells. Fascination is incompatible with transparency: it thrives on ambiguity and mystery. That being the case, this Hedda stands no chance of fascinating.

Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, La duchesse de Polignac , 1782

Finally, regarding this production’s inability to uphold the tragic dimension of Hedda Gabler, let’s make explicit what’s already been implicit. Why does this production fail to go beyond the play’s melodrama? Tragedy arises out of the struggle with oneself, melodrama out of the struggle with others. Ingrid Bergman’s acting is often good, but just as often it is undermined by the mise-en-scène. Indeed, she gives the director the material to bring out the tragic, but he usually opts to focus on the melodramatic instead. So, for example, at the first mention of Løvborg, before he arrives, Bergman succeeds in conveying complex emotion (suggesting internal struggle)—she shows at once excited anticipation and anxious concern—but her acting is sabotaged by the mise-en-scène: it has the effect of portraying her as nothing more that a schemer against others. Similarly, on the several occasions where Hedda shows just how jealous she is of Thea’s intimacy with Løvborg, the mise-en-scène highlights not her struggle with herself but her struggle with Thea. The director thus ignores Ibsen’s subtext, which makes it clear that for Hedda, more important than fighting Thea (that ‘little ninny’) is fighting the return of the repressed that Løvborg triggers, that sexual demon within that would rather have her be Diana the Whore than Thea the Madonna. At the majority of such moments in the play, then, the director opts to highlight the melodramatic and ignore the tragic. Two exceptions are worth noting. The first is when Tesman tells Hedda to ‘stop playing with [her] pistols’: his gesture of restraint evolves into an embrace, while, unseen by him, her laughter transforms into tears. The second occurs when, during Hedda’s first conversation with Brack, she declares that Tesman is ‘a thoroughly worthy man’: the camera captures her not believing what she is saying and, at the same time, desperately trying to believe it. Such moments of grace in which the tragic shows through are, however, all too few: this production has opted to turn Hedda Gabler into just another potboiling melodrama. Pity.

Élisabeth Vigée le Brun, Varvara Ivanovna Ladomirskïa, 1800

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments