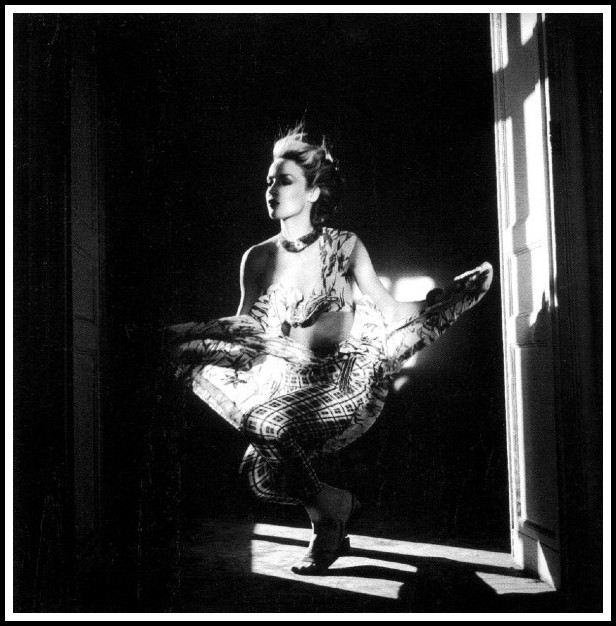

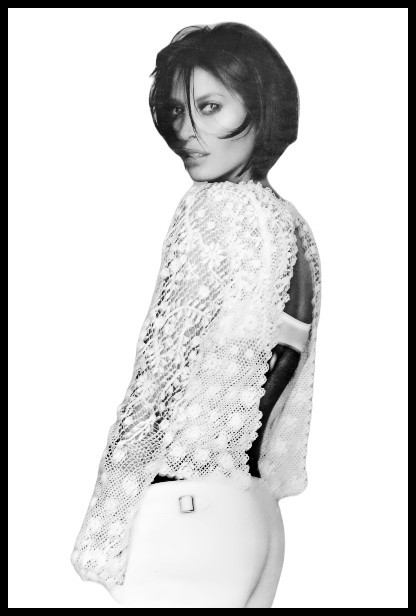

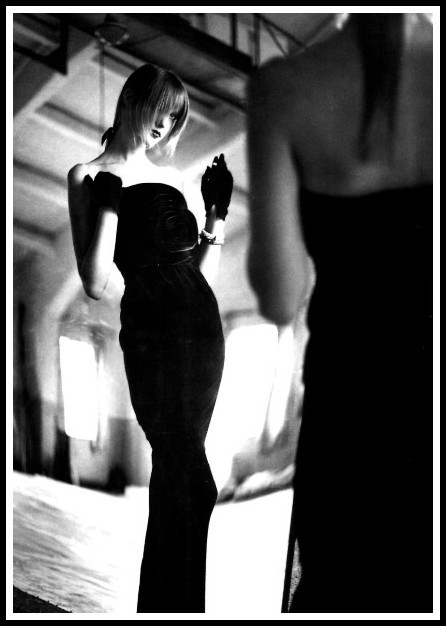

PART 1 – I. INTRODUCTION | II. HUMANWORLD – THE FIRST SIX SONGS | PHOTO: DOMINIQUE ISSERMANN, MILLA JOVOVICH, 2003

Humanworld

PETER PERRETT: THE FLAME OF INDIVIDUALITY – PART 1: THE FIRST SIX SONGS

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

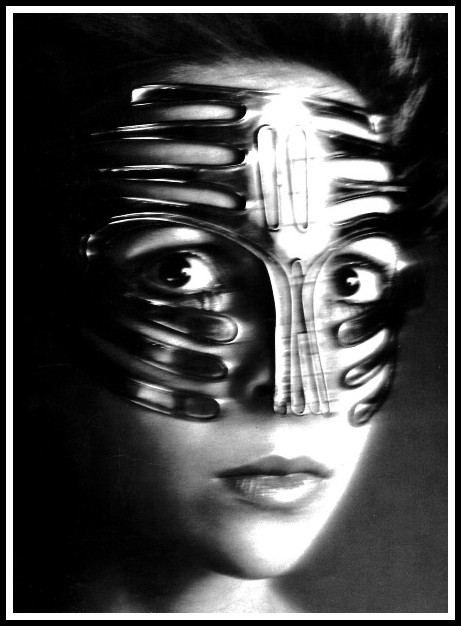

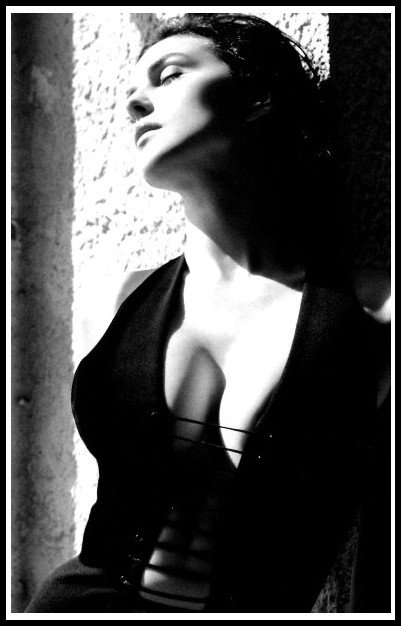

Dominique Issermann, Monica Bellucci, 2003

INTRODUCTION

This essay offers a thematic interpretation of the twelve songs of Peter Perrett’s album, Humanworld.1 Evident in my argument will be a celebration of individuality, a value Perrett embodies and one I strive to uphold. The corporatization of art and entertainment together with the dynamics of the digital industries has brought about the current situation of cultural conformism in which ‘celebrities’ and ‘megastars’ are winners-take-all while far superior talents languish in the ‘long tail’.2 Societies, throughout history, have never much cared for individuality; they developed ideologies to reinforce the pact of obedience on which they are based. There have been times, however, when rebellion against obedience was relatively widely embraced, one of the most recent being the sixties. There is a sense in which Perrett harks back to that time. The neo-classicism of his music inscribes its individuality into a vibrant tradition—a tradition at once of its time and timeless—and thereby affirms what is finest in classic British rock. That today, despite the compelling brilliance of his albums, Perrett languishes in the long tail suggests that hyper-consumerism—the latest ideology aimed at reinforcing the pact of obedience—has shrunk the pool of rebels even as the population has multiplied.3 There’s not much one can do against that, except to celebrate great music that is uncelebrated, and that is precisely what I intend to do now. One final word, however, before we set out on a tour of Humanworld: Peter Perrett makes art, and art, by definition, always escapes capture by any single interpretation. While principled, my interpretations, insofar as they seek to test the theories they derive from rather than to impose them, remain experimental. Got it? Okay, let’s go!

1 – The essay is in two parts, each part a post, with Part 1 addressing the first six songs of the album and Part 2 the last six.

2 – There is ample evidence of this, Peter Perrett on Spotify being a prime example. For an interesting study of this phenomenon from a business perspective in the pop-rock music industry, see Manuel Pacheco Coelho & José Zorro Mendes, ‘Digital Music and the “Death of the Long Tail”’ in the Journal of Business Research, Volume 101, August 2019, pages 454-460.

3 – Hyper-consumerism may be defined as a socio-economic reality in which the sphere of commoditization expands to include an ever-wider range of human activity and ever-more dimensions of human experience. One consequence is that artistic works that do not conform to the codes that facilitate commoditization are excluded from the market when gatekeepers are in a position to block their entry, are crowded out of the market by code-conforming works when they do manage get in, and, again when they do manage to get in, find that vast swathes of the potential audience have simply been zombified by the processes of hyper-consumerism and are incapable of apprehending non-code-conforming works. Anecdotally, I find the evolution in the titles of books investigating the decline of critical thinking quite revealing: The Closing of the American Mind (1987), The Hacking of the American Mind (2017), The Coddling of the American Mind (2018), and Algorithms and Subjectivity: The Subversion of Critical Knowledge (2022). As a follow-up title, may I suggest the following? The Self-Subversion of the American Mind: On the Massive Outbreak of Zombification via Virtual Brain Bypass Operations while ‘Amusing Oneself to Death’ in the Digital Universe. Note that, implicitly, I am making a parallel between the capacity for critical thinking and the power of memory and imagination.

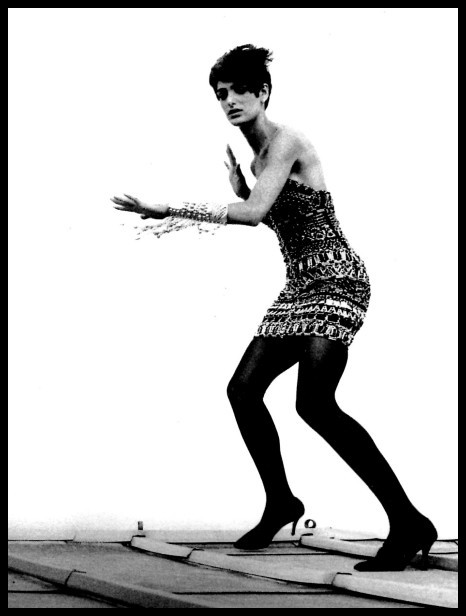

Sylvie Lancrenon, Isild Le Besco, 2004

1. PETER PERRETT | I WANT YOUR DREAMS | HUMANWORLD

A blind man travelling through fog

A vagrant who’s been robbed

A rich man, servant on her knees

Welcome to these streets

Missed opportunities

Pass with every day

The pleasure of what might have been

Is treasure that remains

I want your dreams

Fulfilment in your dreams

I want your memories, vivid and surreal

I want your picture staring back at me

I want to savour every second of that delicious meal

I want your dreams

Fulfilment in your dreams

I want your memories, savagely serene

I want your passion so I can feel

I want to savour every second of that delicious meal

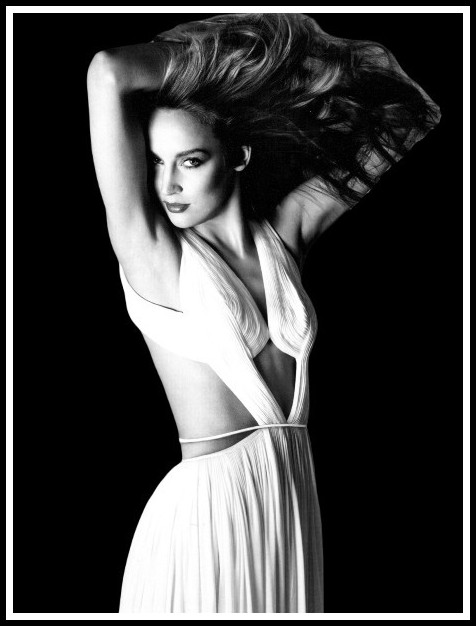

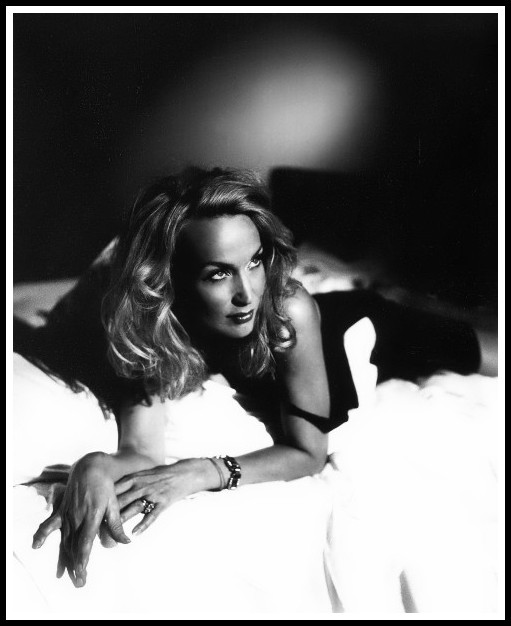

Arthur Elgort, Jerry Hall

Peter Perrett: I’m not a big fan of social media. I think it induces mental illness. That’s a subject some of my songs touch on. ‘I Want Your Dreams’ is about when reality becomes so out of focus that all you’ve got left are dreams and memories, and retreating to those. Music is the safest way of escaping.1 What might Peter Perrett mean by ‘mental illness’?2 A plausible interpretation would be ‘alienation’, a state of devitalization, fragmentation and disconnectedness. This, indeed, is exactly what social media induce: a pseudo-connection with others that entails a de-connection from one’s self; a fragmentation of universality into an infinity-mirror of virtual worlds, the outcome being a state of devitalization best represented by the zombie. Humanworld describes a dystopian present which, back in my youth, would have been an equivalent of Westworld. I saw an old poster for Westworld which said, ‘Where men and women are programmed to serve’. Back in the seventies Westworld seemed like a sci-fi future that would never happen. It was just a really scary film. And then when I woke up, quite recently, I found myself in a world where the future had become more of a nightmare than anyone could have imagined. It’s amusing as well, but… It’s ‘Humanworld’ rather than two separate words because it’s like the scariest horror film.3 By definition, the zombie is one who is alienated from individuality, the process of ‘becoming who one is’ (Nietzsche) through ‘making something of what has been made of one’ (Sartre). The future that has become ‘more of a nightmare than anyone could have imagined’ is the present wherein ‘men and women are programmed to serve’. To serve what? Hyper-consumerism,4 in which ‘having’ overrides ‘being’, the zombie the individual.

1 – Peter Perrett, June 2019 interview, Paris, France 24 TV

2 – Lacking the means to ask him, I can only speculate plausibly, that is to say, in a manner consistent with what he says in his songs and his interviews.

3 – Peter Perrett, June 2019 interview, Paris, France 24 TV

4 – For Perret, the emblem of hyper-consumerism is ‘America’. In this sense, he is very much a European, resisting.

Arthur Elgort, Jerry Hall

As the album opener, then, ‘I Want Your Dreams’ may be seen as a song of resistance, an invitation to connect with one’s memories and dreams—the last refuge from the conformism of consumerism—and to yield to the music, ‘the safest way of escaping’ from Humanworld. The opening verse—’A blind man travelling through fog / A vagrant who’s been robbed / A rich man, servant on her knees / Welcome to these streets’—can be seen as banal reality, harking back to Bowie’s dystopian vision in Ziggy and Diamond Dogs, or, far more interestingly, as a metaphor for today’s digital zombie, surfing in the fog of virtuality while sacrificing their critical faculties in a movement of voluntary servitude. The second verse—’Missed opportunities / Pass with every day / The pleasure of what might have been / Is treasure that remains’—can be interpreted as nostalgia for an unalienated state, one in which the immediacy of being enhances one’s vitality. ‘I want your passion so I can feel / I want to savour every second of that delicious meal’—these lines from the chorus reinforce the singer’s desire to resist the deadening forces of Humanworld: our world today, in which the silence and attentiveness demanded by what the Greeks called ‘care of the soul’—the work involved in becoming an individual—is subverted by the noise and distractions of a virtual world whose be-all and end-all is a hyper-consumerism best served by the zombification of its inhabitants.

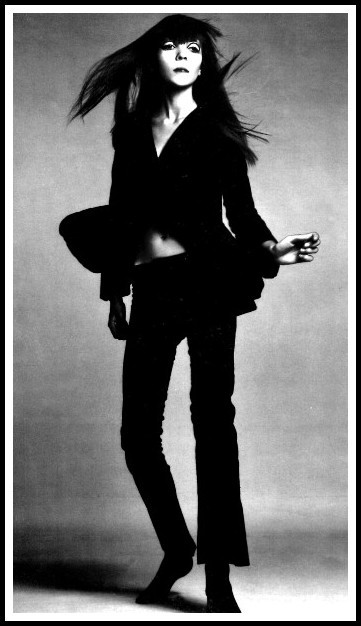

Richard Avedon, Penelope Tree, 1968

2. PETER PERRETT | ONCE IS ENOUGH | HUMANWORLD

Got a friend who’s crazy as fuck

She’s got a heart so big it hurts

The situation seems perverse

If I was young I’d call it love

I don’t want to let you down

Don’t want to get you down

Don’t want to put you in any kind of mess

The writing’s on the wall

One of us will take a fall

I’m ready, I know my place

Got a friend who’s crazy as fuck

She’s got a heart so big it hurts

So many times when once is enough

Convinced herself she don’t need love

If I am out of line thinking about her all the time

I don’t even mind I know she don’t think twice

It’s just a fantasy, there is no you and me

I gotta learn to take my own advice

Wading through the silence that is screaming at me

She left a deep impression and its screaming at me

Once is enough

The past comes back to haunt you

Once is enough

Max Vadukul, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, 1989

Peter Perrett: Luckily there are many different kinds of love. On my first ‘comeback’ album, all the songs were about my wife, who I’ve been married to almost fifty years. I exhausted that subject on that album. I don’t like repeating myself, so all the love songs on the new album are about other females that I know that allow me to fantasize without them telling me to fuck off.1 Such self-lucidity it typical of Peter Perrett. The pride and menace in this hard-driving rocker—propulsive bass, textured Telecaster chords punctuated by loaded Gibson licks, drumming that is all the more effective for giving guitars and bass space—is directed not at the withholding woman but at the midday demon inside the man. ‘Midday demon’, you may know, refers to that force inside an older man that drives him to seek self-renewal through a younger woman.2 The singer knows that humiliation and ridicule await him should he act on his infatuation—’crazy as fuck’ is not the random simile it seems, for ‘fuck’ represents a fulfilment of desire. He knows that the situation is ‘perverse’, that he is ‘out of line thinking about her all the time’; no longer young, he knows it’s not ‘love’, and he knows his ‘place’. Moreover, he knows that were he to cede to temptation, things would unfold as inevitably as in a Greek tragedy: ‘The writing’s on the wall / One of us will take a fall’. He declares his clarity: ‘It’s just a fantasy, there is no you and me’. The temptation persists, however: ‘She left a deep impression and its screaming at me’. Finally, as the singer intones ‘Once is enough / The past comes back to haunt you / Once is enough’, we are convinced by the majesty of the music—its knife-edge incisiveness, its defiant jubilation—that he will vanquish the demon.

1 – Peter Perrett, June 2019 interview, Paris, France 24 TV

2 – The best artistic depiction of the midday demon is, in my view, Luis Buñuel’s film, That Obscure Object of Desire.

Lothar Schmid, Eva Green, 2004

Compact, quick, and utterly compelling, ‘Once is Enough’ amply demonstrates my contention that in Peter Perrett’s music, the tradition of classic British rock—the Who, the Stones, the Kinks—is vibrantly alive and kicking. In it, feeling and form—like the dancer and the dance, the calligrapher and the line—are one. The song’s bracing vitality invigorates, leaving us with a heightened sense of being. What more can one ask of art?

Kate Barry, Elsa Zylberstein, 1998

3. PETER PERRETT | HEAVENLY DAY | HUMANWORLD

You looked like an actress with your lipstick and shades

A glamourous actress at the bank holiday fete

I felt like a teenager out on a date

We rode on the dodgems, it was a heavenly day

One more day in heaven, a heavenly day

A final day in heaven, a heavenly day

It was so romantic as we walked through the park

I wanted to hold your hand but I was too scared to ask

We were the only people alive in the world as we sat on the grass

If only I could freeze that moment in time so it would never pass

One more day in heaven, a heavenly day

A final day in heaven, such a heavenly day

The sun was incessant, not a cloud in the sky

That milky white skin on your glistening thighs

Infinity mirrors in the depths of your eyes

Infinity mirrors in the depths of your eyes

One more day in heaven, a heavenly day

A final day in heaven, such a heavenly day

Infinity mirrors in the depths of your eyes

A final day in heaven with your eyes

Richard Avedon, Jerry Hall, 1979

To those fixated on his Prince of Darkness persona, Peter Perrett’s ‘Heavenly Day’ must come as something of a shock. Memory and desire mingle in the mind of an old man as, in the company of a woman, he spends an afternoon in the park. The innocence of childhood (‘we rode on the dodgems’), the tentativeness of adolescence (‘I wanted to hold your hand’), the stirrings of eros (‘your glistening thighs’) entrance the man as the echoes of his youth resonate in the present moment. If memory is the past tense of desire, this vignette/song is a fine emblem of it. Too experienced not to know this moment is unlikely to be repeated (‘a final day in heaven’), too innocent not to have his heartstrings tugged by her ‘lipstick and shades’ and ‘milky white skin’, the man is aware that past, present and future are conspiring to burn this day into his memory: memory is the past tense of desire.

Gilles Bensimon, Christy Turlington, 2002

In ‘Heavenly Day’, Peter Perrett once again succeeds in bringing forth a felicitous blend of feeling and form. Indeed, the theme of the lyrics—memory and desire—is brought into magnificent tension by the music. Repetitive and insistent, it builds, like Ravel’s Boléro, into one long, gradual crescendo as the sound thickens and amplifies. The mechanical quality of the music, its obsessive ostinato rhythm, gives the song an edgy majesty that prevents the sweetness of the lyrics from becoming saccharine. The slow-flowing molasses of Peter Perrett’s voice, too, has just enough of the deadpan in it to keep the words from becoming cloying. The song isolates a magical day in a park that is the meeting place of old-age and youth. While the lyrics celebrate the purity of an evanescent moment, reminiscent of youth, the music asserts that the singer ‘will not go gentle’ into the ‘good night’ of old age. If ‘Heavenly Day’ is an incursion into Phil Spectorish pop, Perrett has succeeded in giving the 3-minute epic a beyond-teen texture, proving that nostalgia can be more than self-indulgence.

Gilles Bensimon, Christy Turlington, 2000

4. PETER PERRETT | LOVE COMES ON SILENT FEET | HUMANWORLD

I can’t protect you but I wish I could

I can’t protect you but I wish I could

It’s well-known that love’s gonna be

Where you least expect it

It’s well-known that love’s gonna come

You know they say that love comes on silent feet

I can’t forget you but I wish I could

I can’t forget you but I wish I could

It’s well-known that love is a thief

When you least expect it

It’s well-known that love’s gonna steal your heart

It’s coming on silent feet

How do you know if you don’t try

Don’t be afraid of feelings inside

I stand corrected but I’m on my knees

I stand corrected but I’m on my knees

It’s well-known that love’s a disease

And you’ve been infected

It’s well-known the damage that’s done

You know they say that love comes when no-one’s home

Ruven Afanador, Vanessa Paradis, 2004

The theme of erotics and aesthetics, eros and creativity, is a rich one in the history of art. The available facts of Peter Perrett’s biography all attest to the intensity of the eros-creativity dynamic in his work. Like Rodin in sculpture, Picasso in painting, Jim Morrison in poetry and Henry Miller in fiction, Peter Perrett thrives creatively when love and sex—without obligation (duty) and sanction (morality)—are active in his life. Memory and imagination are also in the mix, as are reality and fantasy. If this seems self-evident, let us recall that the gift for love is unevenly distributed, that erotic grace is far from being commonplace. Now, nowhere in Perrett’s biography will you find the vulgarity of conformism, the ugliness of convention, or the misery of ‘morality’ when it comes to his relations with women. If, as the evidence indicates, he is blessed with the grace of Eros and the gift for love, then is it any wonder that he needs to feel the tug of love/sex in order to create? And this all the more after his long ‘hibernation’? ‘Love Comes on Silent Feet’ is not a song about the insidious worming of love into the innocent apple of a life; instead, it is a song about Peter Perrett’s need to feel the tug of love/sex in order to write.

Ruven Afanador, Vanessa Paradis, 2004

The tropes of love as a thief (‘gonna steal your heart’), love as a disease (‘you’ve been infected’), and love as a burglar (‘comes when no-one’s home’) are all used in a generic context in ‘Love Comes on Silent Feet’. This absence of an individualized context supports my assertion that the song is not about ‘the dangerous presence of love’ but rather about the threat to creativity from the absence of love. The writer working out chords on his guitar spurs himself on by recalling creativity’s requirement of risk-taking (‘How do you know if you don’t try / Don’t be afraid of feelings inside’) and by reminding himself that self-abasement is a pre-requisite for self-elevation (‘I stand corrected but I’m on my knees’). Lucid, the writer knows that making himself vulnerable to love is more creatively rewarding than protecting himself from it, and that the ‘damage’ love does comes with the promise of a breakthrough to something new. In ‘Love Comes on Silent Feet’, then, it is not the tension between the lyrics and the music (as in ‘Heavenly Day’) that drives the song, but rather the tension between the text (‘beware of love’) and the subtext (‘be open to love’).

Gilles Bensimon, Mellisia Hill, 2002

5. PETER PERRETT | THE POWER IS IN YOU | HUMANWORLD

The days of hope

The days when the future was clear and bright

And the bells were ringing out for freedom

It’s gonna be that way again

We’re gonna see those times again

You made it this far against the odds

The power is in you

Those balmy days

Through the summers, peace and love

And the kids were on the streets for freedom

It’s gonna be that way again

We’re gonna see those times again

You made it this far against the odds

The power is in you

The power is in you

What you gonna do

When the power is in you?

The end of days

In the winter of our discontent

We are gonna find the road to freedom

It’s gonna be that way again

We’re gonna see those times again

You made it this far against the odds

The power is in you

Ellen von Unwerth, Naomi Campbell, 1986

Jamie Perrett: My father’s extremely political, and if I’m ever in an interview with him I always say, ‘Just don’t talk politics!’, because he’ll start ranting. I mean it’s such a divisive topic.1 I am inclined to agree with Jamie, but politics is so present in Peter Perrett’s post-Only Ones work that I shall take up the challenge of addressing it. ‘The Power Is in You’ is a political song, a message from a Sixties teenager, now 67, to a younger generation. Let us adopt a comparative perspective and look at it alongside John Lennon’s ‘Power to the People’ and Patti Smith’s ‘People Have the Power’. Lennon’s song is a street chant for a militant march, blaring and percussive; Smith’s is a visionary incantation, a dream in which it is decreed ‘the people rule’. Both songs are written to arouse the masses to revolution. Peter Perrett, in his song, takes an entirely different take. Bathed in the glow of nostalgia, the song evokes ‘Those balmy days / Through the summers, peace and love / And the kids were on the streets for freedom’. Recognizing the hard times they’ve lived through, it conceives of the younger generation as survivors (‘You made it this far against the odds’) and offers them the promise of a return of the spirit of the sixties (‘days of hope’, ‘future clear and bright’, ‘bells ringing out for freedom’). Perrett, estranged from the present and its instruments of alienation, harks back to a utopian vision of the past; aligning himself with youth, he declares ‘The end of days / In the winter of our discontent / We are gonna find the road to freedom’. Is the song not a pitiful pipe dream, you may wonder; is it not hopelessly naive? I will argue the opposite.

1 – Strand Magazine, In Conversation with Jamie Perrett

Patrick Demarchelier, 1986

History shows that ‘rule by the people’ equates to rule by a clique of fanatics who quickly become murderous, justifying their tyranny by whatever ideology provides the most convenient cover. From this point of view, it is Lennon and Smith who are ‘hopelessly naive’. Peter Perrett, instead of haranguing a crowd in the street (Lennon) or exhorting them to dream (Smith), chooses to speak gently to someone who, one senses, is alone in a room with him. The mode of the song is one of intimacy, not militancy; the hope offered derives from lived experience, not myth and dream (Smith) or feel-good simplifications (Lennon). Perrett sings, ‘The power is in you / What you gonna do / When the power is in you?’. Having borne witness to a past where authentic feeling was not corrupted by the machinery of commodification (social media) and facts could dispense with fig leaves (truth could be naked), the singer by his question—’What you gonna do?’—leaves his listener to bear the responsibility that inheres in one who would be free. For a singer who hopes to foster change, such respect for the individual is more likely to be transformative than rallying cries for crowds .‘The Power Is in You’ may convey a nostalgic vision of a long-lost utopia, but its insistence on individual responsibility safeguards that ideal from the group dynamics that inevitably turn utopian dreams into dystopian nightmares.

Richard Avedon, Penelope Tree, 1967

6. PETER PERRETT | BELIEVE IN NOTHING | HUMANWORLD

Believe in nothing, nothing’s in town

Expectation just lets you down

It’s not a time of hope, living is a joke

Blackest hole is drawing us in

Bleakest future there’s ever been

It’s not a time for hope, living is a joke

I’m gonna sleep on a bed of nails, never to wake up

Believe in nothing, nothing is real

If you ain’t got nothing, there’s nothing to steal

It’s not a time of hope, living is a joke

Believe in nothing, there’s nothing to find

You’re free, there’s nothing on your mind

Trying to make some space, a completely empty place

I’m gonna sleep on a bed of nails, never to wake up

Believe in nothing, nothing is safe

Even your saviour’s fallen from grace

It’s hard keeping strong when everything’s gone wrong

Believe in nothing, the world is insane

You’re playing in a rigged game

They keep telling you, you’ve only got yourself to blame

I’m gonna sleep on a bed of nails, never to wake up

Dominique Issermann, Monica Bellucci, 2003

In ‘Believe in Nothing’, Peter Perrett takes a stance opposed to the ‘We’re-going-to-find-the-road-to-freedom’ one he adopted in ‘The Power Is in You’. Positioning himself at the crossroads of nihilism and depression, he sings, ‘Blackest hole is drawing us in / Bleakest future there’s ever been / It’s not a time for hope, living is a joke’. Nietzsche, once again, can help us gain a perspective on Perrett’s position: Nietzschean nihilism is a fundamentally personal phenomenon, experienced by the individual. It occurs when one comes to recognize that those structures once thought to give meaning to one’s world and life fail to eradicate life’s absurdity. In nihilism, a felt need for meaning—a compulsion to make sense of life’s absurdity—exists alongside an acknowledgment that life and the world are meaningless. In short, the nihilist is one who consciously experiences the tension between his need for meaning, order, or sense and his recognition that his world is absurd or meaningless.1 As for depression, an observation by Adam Phillips is useful here: Depression is a self-cure for the terrors of aliveness, of being alive to one’s losses and therefore to one’s desires. From a psychoanalytic point of view, imagination—the capacity for representation—begins, or rather, is initiated, by the experience of loss.2

1 – Adapted from Kaitlyn Creasy, The Problem of Affective Nihilism in Nietzsche: Thinking Differently, Feeling Differently (Springer International, 2020) p. 14

2 – Adam Phillips, On Flirtation (London: Faber & Faber, 1994) p. 82

Bettina Rheims, Monica Bellucci, 2007

We notice, in the lyrics, the blurred line between the singer speaking for and addressing himself (‘Expectation just lets you down’, ‘It’s hard keeping strong when everything’s gone wrong’, ‘They keep telling you you’ve only got yourself to blame’) and speaking as a ‘sage’ addressing a ‘you’ (‘Believe in nothing, nothing is real / If you ain’t got nothing, there’s nothing to steal’; ‘Believe in nothing, nothing is safe / Even your saviour’s fallen from grace’; ‘Believe in nothing, the world is insane / You’re playing in a rigged game’). There’s a certain pathos in this, for the listener soon understands that the singer’s two stances—detached sage and implicated speaker—are really one: presenting his own experience as universal, he has the ‘good manners’ to spare us the directness of a scream or a cry and to adopt, instead, a stance of indifference (indifference being, like humour, the politeness of despair). This tension between an individual and a universal fate is resolved when, in the chorus, the singer finally comes out and says ‘I’: ‘I’m gonna sleep on a bed of nails, never to wake up’. The ‘bed of nails’, of course, is a device for self-obliteration, a way to induce a numbing pain and so efface feeling. Why would the singer want to lie on it, ‘never to wake up’? Nietzsche’s nihilist is one who feels compelled to seek out the truth even when he recognizes it does not exist; he feels driven to find a meaning and purpose for existence even when he believes there is no such meaning to be found.1 The bed of nails, then, offers a way to dissolve the dilemma of meaning, to stop being a dog chasing its tail (‘Believe in nothing, there’s nothing to find / You’re free, there’s nothing on your mind / Trying to make some space, a completely empty place’). Nihilism does not permit of general solutions: it is something all individuals might come to face, yet it is also something that we can only come to know—and learn to overcome—in the singularity of an experimental life.2 In ‘Believe in Nothing’, with its expression of a Nietzschean nihilism, Peter Perrett hints at his singularity, ‘the singularity of an experimental life’. Against the crowd, against conformism, he thus affirms individuality.

1 – Adapted from Kaitlyn Creasy, The Problem of Affective Nihilism in Nietzsche: Thinking Differently, Feeling Differently (Springer International, 2020) p. 14

2 – Ibid.

Jerry Hall, London, 2001

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments