I. INTRODUCTORY NOTE | II. STRINDBERG’S VILLAINS: THE NEW WOMAN AS PREDATOR

MISS JULIE: DRAMA OF THE SEXES – PART 1

STRINDBERG’S VILLAINS: THE NEW WOMAN AS PREDATOR

Declan Kiberd

Posted by kind permission of Declan Kiberd, Professor Emeritus, University of Notre Dame

From Declan Kiberd, Men and Feminism in Modern Literature (London: Macmillan, 1985) pp. 40-47

Fernand Khnopff, Rote Lippen, 1897

I. INTRODUCTORY NOTE BY RICHARD JONATHAN

This post is the first in a series of four on Strindberg’s Miss Julie. In it you will find Declan Kiberd’s trenchant analysis of the play from the perspective of Strindberg and the ‘new woman’. Post 2 consists in a major essay by Jessica Benjamin, ‘Sympathy for the Devil: Notes on Sexuality and Aggression, with Special Reference to Pornography’, preceded by a brief essay by Richard Jonathan and a short excerpt from Sylviane Agacinski’s book, Drame des sexes: Ibsen, Strindberg, Bergman. The remaining posts in the series are by Richard Jonathan. The first of these, Post 3, presents a critical comparison of Mike Figgis’ film version of the play with that of Liv Ullmann. Finally, Post 4 offers an analysis of Philippe Boesman and Luc Bondy’s opera of Miss Julie. (Note that Posts 3 and 4 will be online by 30 April 2023.)

Fernand Khnopff, White Mask, 1907

II. STRINDBERG’S VILLAINS: THE NEW WOMAN AS PREDATOR

DECLAN KIBERD ON ‘MISS JULIE’

Strindberg’s mastery of the art of inversion is triumphantly demonstrated in Miss Julie, a play whose plot hinges not only on the discrepancies between the sexes, but also on the differences between the classes. This bleak drama tells of how an aristocratic young lady seeks to seduce a manservant of her father in a short, sharp, pointless relationship which culminates in her suicide. Here, unlike in The Father, it is the woman and not the man who will die rather than lose honour. The manservant, being of the lower orders, can survive and prosper untrammelled by the self-destructive aristocratic notions of ‘face’ and ‘reputation’. It is Strindberg’s implication that he is the truer aristocrat, who uses brain and muscle to survive, and that Julie, like Hedda Gabler, is the last of a decadent aristocratic line, which somehow or other finds the saving grace to abolish itself. The shrewd and the resourceful will inherit the earth from those whom they supplant, and in his preface to the play the author claims to uphold this Darwinian belief.

Fernand Khnopff, Who Shall Deliver Me?, 1891

Yet his drama is a great deal more subtle, in its insistence on how much both classes have in common, if only their pretensions to other ways of living. While Jean the servant affects a taste for wine, Miss Julie prefers the workingman’s beer. While Jean insists fastidiously on heated plates for dinner, Miss Julie dances with gamekeepers and doubtless follows her mother’s example in wearing dirty cuffs. Moreover, the play has not progressed far before each character is caught in some glaring contradiction on the question of the classes. At one stage, Jean can plead the cause of the lower orders and, at another moment, dissociate himself from the riffraff at the dance. Miss Julie can disown her aristocratic background, while at the same time issuing peremptory orders. The ultimate effect of all this is to throw into question the notions of rank and degree. If humans are at once so pretentious and so interchangeable, then a class-based society is a farce. The differences between the classes may be erased in due time, if we are to judge by the relations between Miss Julie and Jean; but the sexual differences between men and women are shown by Strindberg to be tragically irreconcilable.

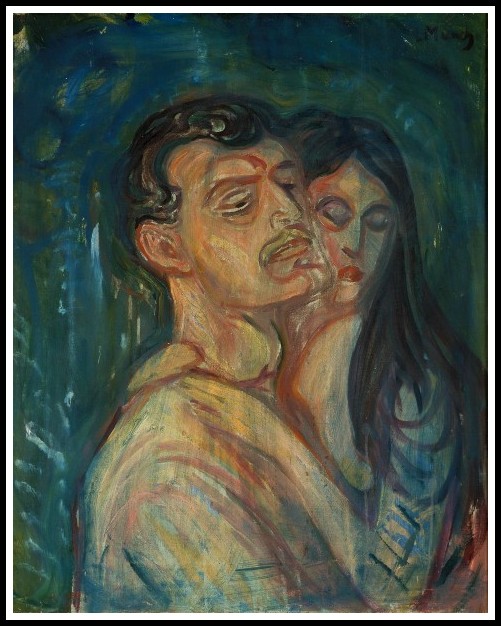

Edvard Munch, Head by Head, 1905

By making his heroine an aristocrat, the playwright is testing the hint, thrown out in The Father, that women rather than men are nature’s aristocrats. But it is not long till he comes to a more complex conclusion. Miss Julie may be the social aristocrat on this particular stage, but Jean is undoubtedly the sexual aristocrat, ‘because of his male strength, his more acutely developed senses, and his capacity for taking the initiative’ (Preface). So the scales at the start are finely balanced, as the traditional constraints on women are mitigated by Miss Julie’s rank. In this sense, the plot is an outright reversal of the norms of classic melodrama, where the tyrannical overlord exercised his droit de seigneur over a luckless maidservant whom he left in the lurch. All through the nineteenth century, the maidservant had been the major sexual opportunity of a closed and prurient society. ‘Economic control seemed to guarantee erotic control’, writes Mary Ellmann, ‘and for the sadistic, exceptional rights of discipline lay in the relationship of employer and employee’. Indeed, she cites an event from Strindberg’s own youth, when a maidservant uncovered his body as he slept, for which crime he was entitled to whip her. ‘Both to their own diversions’, comments the acid lady critic, but one can appreciate just how fascinating to a mind like Strindberg’s was the prospect of inverting the sexual identities of the protagonists in this particular situation.

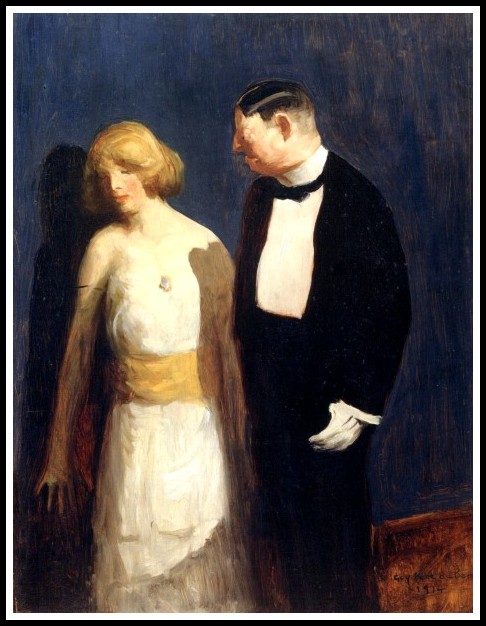

Guy Pène du Bois, The Doll and the Monster, 1914

Miss Julie is introduced as a predatory version of the New Woman, a man-hater who makes her fiancé jump like a dog, while she flails his back with a whip. It is not clear whether he or she breaks off the engagement but, given such exotic behaviour, it is not hard to guess. Soon her interest is aroused by the manservant Jean. She invokes her rights as an employer in order to compel him to keep her company, but with due decorum he insists that he was not hired to be her playmate, that he is above that. Already, however, their personalities are beginning to merge. Whereas Jean had earlier pronounced Miss Julie too haughty in some respects, and too abject in others, now he tells her that he is proud in some ways, if not in others. That may, of course, be just a ploy to whet her interest. At any rate, one of the fascinations of the play is the way in which the initiative ebbs and flows, now to Julie, now to Jean. Character develops in a jagged fashion in the work of this playwright, whose greatest gift is to hint constantly at levels of meaning below the surface of things. It is never fully clear whether Jean is exciting his mistress by passive provocation, or whether she is actively seducing him. Strindberg may not even know himself, but may simply be anxious to show how, in the decisive moments of their Jives, people often act under the sway of forces which are not fully clear to them at the time.

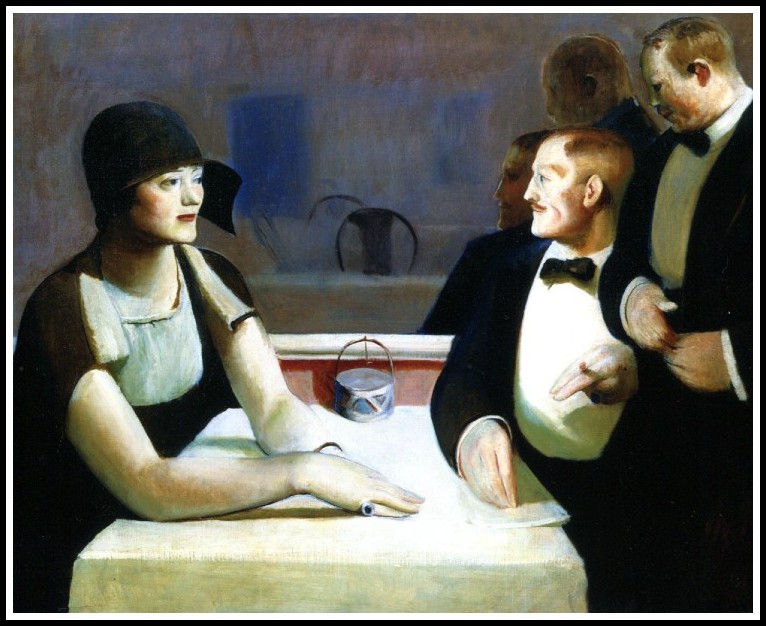

Guy Pène du Bois, Mr. and Mrs. Chester Dale Dine Out, 1924

At all events, one moment Miss Julie is teasing the reluctant Jean into a mild flirtation, and the next she is cravenly begging this servant, who has violated her honour, to take her away from her father’s house. She tries to clothe her erotic adventure in the idiom of romantic love, but Jean cruelly reminds her that she has only done what many others have done before her. At heart, she knows that his power over her was the spell which the strong will always cast over the weak, the man on the rise over the woman on the wane. Yet inconsistencies remain. She professes to have divested herself of aristocratic pretensions, yet cannot bear the prospect of public outrage at her loss of honour to an underling. He professes to be a democrat, yet anticipates with relish the prospect of Swiss citizens prostrating themselves before his porter’s uniform. He protests that men are all the same at root, yet finds it hurtful to learn that the aristocratic glamour of Miss Julie is so insubstantial. He talks as if he already felt himself above her, yet he will quake before the return of her father at the end. In the meantime, he dreams of escape with Miss Julie in an alliance based not on a self-deluding love, but on a shrewd sense of mutual material self-interest. While she toys with this proposal, Miss Julie recounts the details of a life that has turned her at once into a ruined aristocrat and a New Woman.

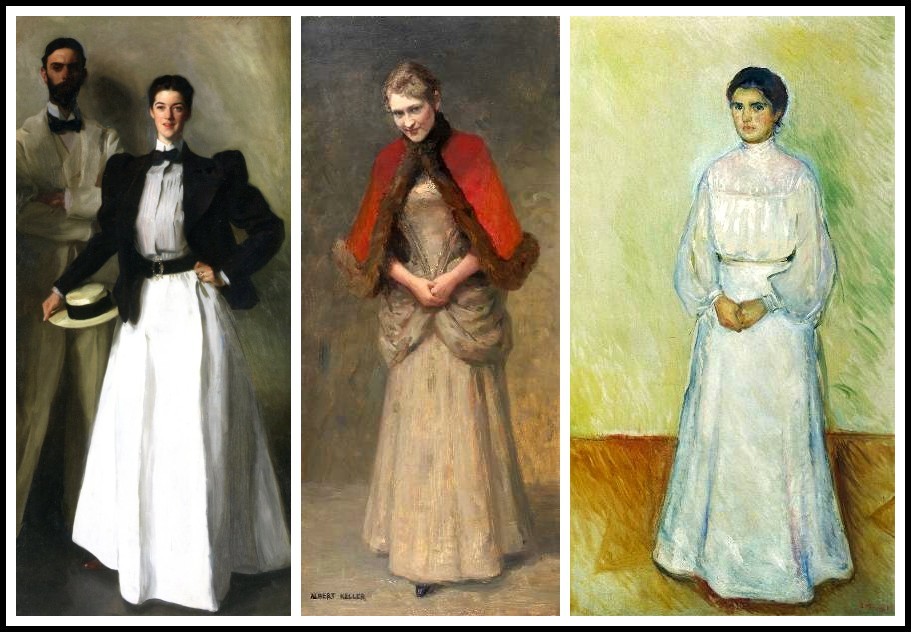

J.S. Sargent, Mr. & Mrs. Phelps Stokes, 1897 | Albert von Keller, Adele von Le-Suire, 1887 | Edvard Munch, Ellen Warburg, 1905

Her tale might be that of the Captain’s daughter in The Father, for in this case, too, the androgyny of the child is less a source of hope than an outcome of revenge. Strindberg does not see in it the promise of an integrated personality, but the signs of a bitter battle between husband and wife. For Miss Julie came into the world, unwanted by her frustrated mother, who created a manly daughter in order to revenge herself on her hated husband, and to free the child from the necessity of repeating her own error of dependence on a man. In addition to her conventional training, Miss Julie was made to wear boy’s clothes, perform boy’s chores with horses, and given a harsh training, in order to demonstrate the mother’s thesis that a woman is as good as any man. In retrospect, it is dear that the androgyny of Miss Julie appeals to her mother not only as a source of revenge, but also as a mode of consolation. The lonely woman, estranged from her husband, liberates the hidden male in her daughter in order to console herself for the lack of a man in her deepest emotional life. She recreates in her daughter the male companion she cannot find in her husband; and, while she defrauds her husband in business and betrays him in life, she teaches her daughter to vow eternal enmity to the male sex. Her coup de grâce is to run the family estate as a kind of inverts’ colony, where men perform domestic chores and women undertake the heavy laboring, with the result that it falls into ruin.

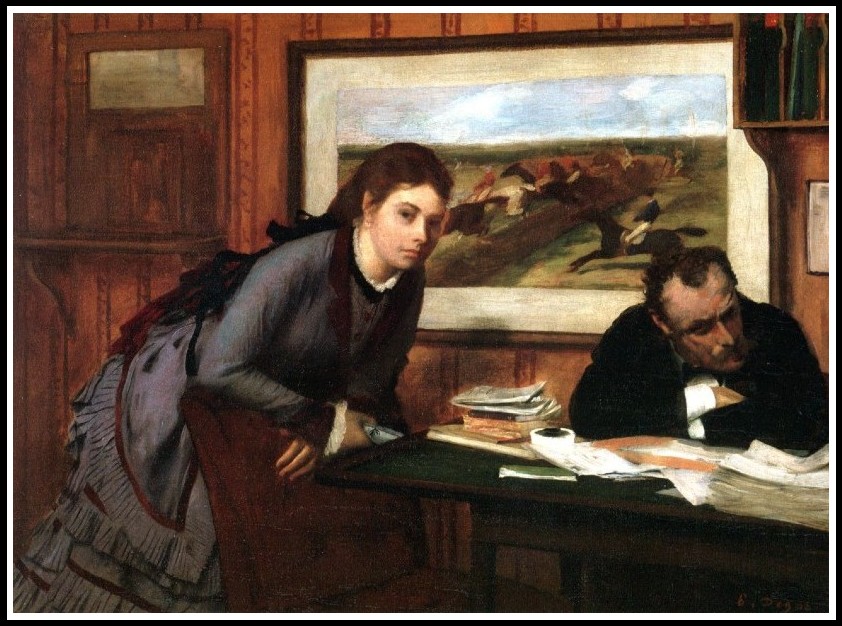

Edgar Degas, Sulking, 1870

Miss Julie lives out the implications of this devastating programme of female revenge. She becomes engaged to the county prosecutor, with the purpose of whipping him into submission. Bored with this diversion, she gives her body to the servant Jean and plays on his bad conscience in an attempt to lure him into marriage. She reminds him of what a man owes to a woman of whom he has taken advantage, but his only reply is to toss her a coin and to make a thoroughly Strindbergian complaint against the law which provides no punishment for the woman who seduces a man. In this, at least, he exposes the radical inconsistency of Miss Julie, who claims all the freedoms of a man, while continuing to assume all the traditional privileges of a woman. Moreover, in contrasting the sexual attitudes of the aristocracy with those of their servants, he exposes the greatest flaw of all in Miss Julie, the fact that, like all those with the leisure to make of love a complex art, she is nothing less than preposterous in the expectations which invests in her own sexuality. She commits the error of seeking in sex the enlightenment which men once expected only from the deepest experience of religion.

Edvard Munch, Consolation, 1907

Jean rebukes her for it:

Miss Julie, I know you must he suffering, but I can’t understand you. We have no such strange notions as you have, we don’t hate as you do! To us love is nothing but playfulness, we play when our work is done. We haven’t the whole day and the whole night for it like you! I think you must be sick.

This cuts to the heart of Strindberg’s critique of modern sexuality. He knows that with the massive opportunities for leisure among all classes, what was once a merely aristocratic affectation has now become the besetting vice of nations. The element of play has rapidly been lost in sexual relationships, which are now conducted with a solemn self-analytical intensity once the preserve of mere aristocrats. The substance of Jean’s complaint is that people like Miss Julie now approach lovemaking with a puritanical solemnity. The art of love has grown so morbidly self-conscious, as Christopher Lasch has drily observed, that it is now a surprise to encounter a manual in which the epithet ‘sexual’ is divorced from the noun ‘performance’. ‘Froken Julie, c’est moi’.

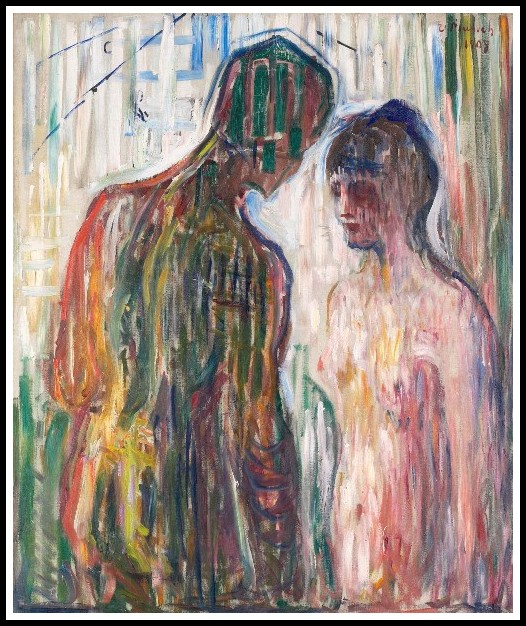

Edvard Munch, Cupid and Psyche, 1907

It was not always so. In medieval times, sex was a boisterous game which provoked even children to riotous mirth, and this attitude lasted down to the seventeenth century. Only then was playful sex converted into serious discourse. Thereafter, according to Michel Foucault, the flesh was deemed the source of all evil, and the moment of transgression was located not in the act of sex, but in the stirrings of desire. The search for ‘occasions of sin’ in dreams and actual situations gave rise to a self- conscious discourse, which resulted in the displacement and intensification of desire itself. Whereas the ancient ars erotica involved the search for pleasure for its own sake in a secret lore shared only by master and disciple, the modern science of sex must measure pleasure in relation to the law of the permitted and the forbidden, in a confessional rhetoric which exposes all secret discoveries to public scrutiny. Foucault holds that a scientia sexualis usurped the ars erotica and men who had feared that they could imagine no new pleasure surprised themselves with their pleasure in the knowledge of pleasure. After the seventeenth century, such knowledge became the preserve of the upper class, but for a long period the lower classes escaped the dubious privilege of a self-monitored sexuality. As Jean hints to Miss Julie, those whose task is to fill a day with work are not expected to cultivate theories of pleasure or to degrade sexuality into a science.

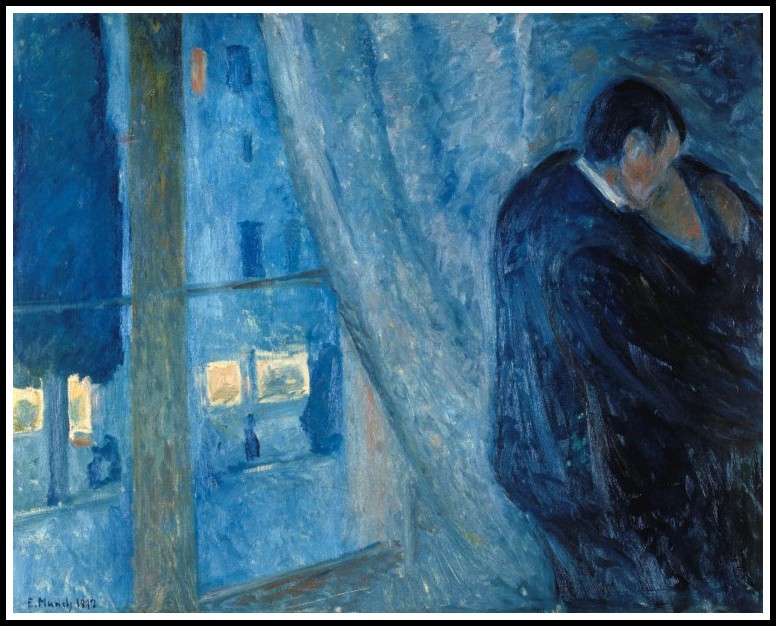

Edvard Munch, Kiss by the Window, 1892

Although workers were shamelessly repressed in economic and political affairs, their sexuality went unrestricted by rulers forever anxious for cannon-fodder. For centuries, these leaders were concerned only with the sexual health and primogeniture of the aristocracy, whose lives were constantly hedged with rules. Only when the workers discovered the wonders of birth control, says Foucault, did the upper classes initiate a crusade for the conversion of the masses to true morality. With the emergence of the bourgeoisie, the old aristocratic obsession with blood lineage was replaced by the modern concern for heredity. Families were no longer symbolised by heraldic crests but by hereditary ailments, like the syphilis inherited by the son in Ibsen’s Ghosts or the decayed teeth of artistic sons in the burgher families of Thomas Mann. Miss Julie perfectly epitomizes this bankruptcy of the aristocratic ideal as it faces the exactions of the bourgeois world. She is the last of her line. Her coat of arms will be broken against her coffin, for she has been destroyed by a mere family ailment. From her parents she has inherited thinned blood and an over-fastidious sexuality. Already, as she borrows ideas and sentences from her servant, she exudes that longing for death which is at the root of all plagiarism. Her personality is one that has lived through the consequences of its own extinction before it has even begun to exist.

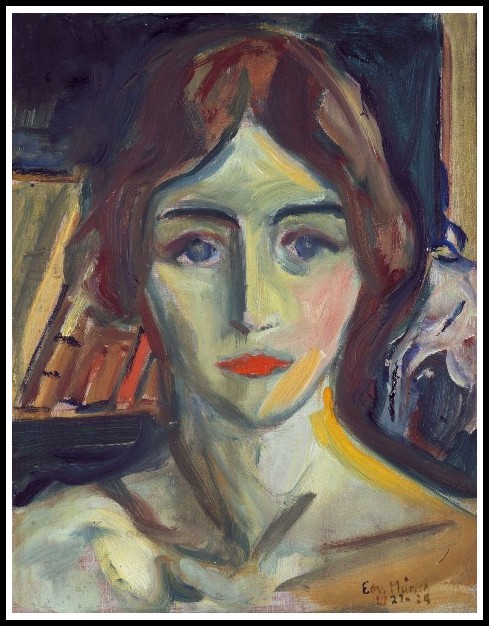

Edvard Munch, Birgit Prestøe – Portrait Study, 1925

Yet she retains at least one trait of the old aristocracy to which Jean could never hope to aspire, the capacity for excruciating self-analysis. ‘Stop thinking, stop thinking’, yells Jean, as she goes out to die rather than lose honour. But she cannot. In this, too, Miss Julie inverts the norms of her sex, to which it was not given to engage in protracted self-analysis of sexual options. By convention and tradition, women did not elaborately plot proposals but simply offered a direct response to an overture. Denied the time for extended self-appraisal (which was the privilege of the male lover), their position in that respect resembled that of the lower orders. Jean implies this in stating that the class difference between himself and Miss Julie is ‘the same difference as between man and woman’.

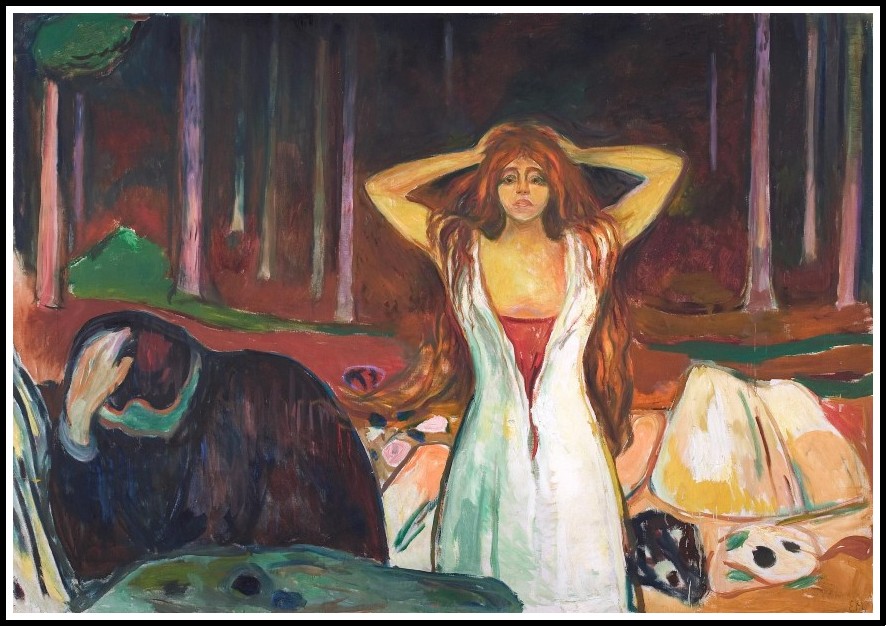

Edvard Munch, Ashes, 1925

It is Miss Julie’s tragedy to bear the burden of an overwhelming guilt, yet never to have an assured sense of the self which sinned. Her plight repeats that of Arthur Dimmesdale in The Scarlet Letter. He, too, has done no wrong, but is tortured by shame and guilt, precisely because the convicting intelligence is so much stronger than the offending instinct. Miss Julie’s sexual impulses are weak and uncertain, but it is her hyperactive mind which finally divests her of any sense of self. Instead, her tortured self-analyses disintegrate her own personality into a series of impersonations learned from others: self-contempt acquired from a father who taught her to distrust women; hatred of men imbued from a fanatical mother; aristocratic pride learned from both; egalitarian principles learned from her fiancé. Such attributes do not coalesce to form a definite personality which is greater than the sum of its parts. Instead, each quality manages to cancel another out, leaving Miss Julie prey to an inauthenticity which is all the more painful because she has just enough intelligence to know how little she really has. Unlike Kristin, she cannot offload her moral scruples onto a comforting but mindless Christianity. As Strindberg wrote in Vivisections, ‘an individual who does not think for himself has, because of this very fact, a vigorous belief in himself.’ Miss Julie, on the other hand, has the courage to accept responsibility for a self which she is doomed never to know.

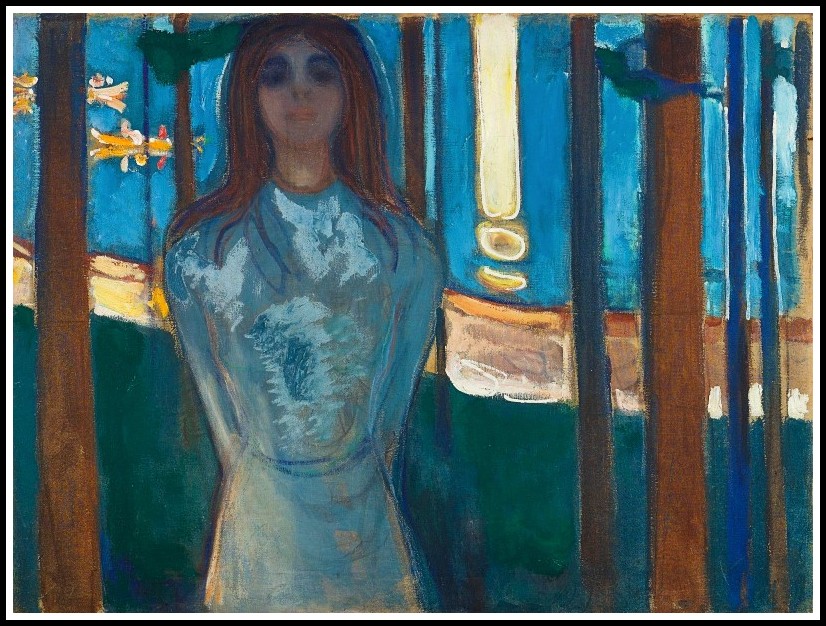

Edvard Munch, Summer Night – The Voice, 1896

In the end, she kills herself because she has no self to kill. Her plight is that of the ventriloquist’s dummy, held accountable for the vices of its master. If there is something histrionic and stagey about her actions and inactions, that is only because the naturalist who has abolished God is left feeling like an actor of bit parts. The dummy remains after the master ventriloquist has gone, marooned onstage without a script or the possibility of action. Miss Julie’s plight is that of a broken aristocracy, but also, by inference, that of all modern democrats who must share in the civilized disabilities of the aristocracy if they want to live in a world where every man is a king. In the world of the sovereign self, no self has any final sovereignty. Mass democracy is simply the freedom of the masses to conform to a culture of mediocrity, where the admired images will be chosen by the vulgar rather than the fastidious. ‘Oh, I am so tired’, says Miss Julie, ‘I have no strength to do anything, not even to feel repentant, or to get away from here or to stay here, to live or to die! Help me, please! Order me to do something, and I’ll obey like a dog.’

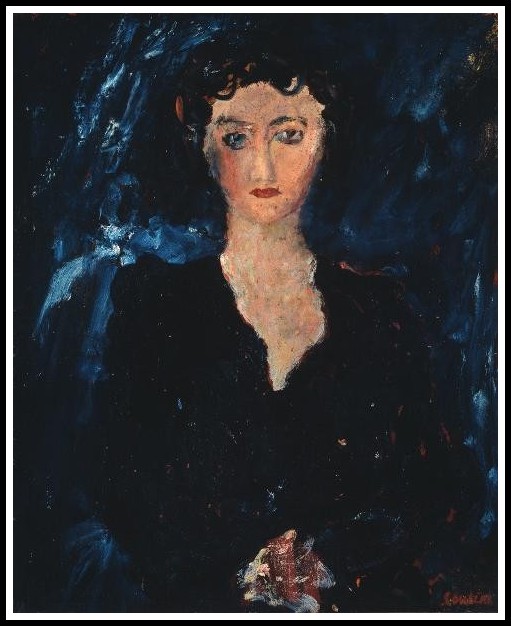

Chaim Soutine, Portrait of a Lady, 1928

The last words of this doomed aristocrat become the theme song of democratic man, who may inherit the earth, but not the ability to rule it. The old repressive regime has built a replica of itself in the head of the porter who, once he has donned his serving man’s coat, lacks the willpower to give orders to his master’s daughter. Conditioning is everything, the self a puny tabula rasa which simply records the inexorable traces of that social conditioning. The lower orders would gladly cut their own throats at the request of their masters, but left to their own devices, they are as incapable of purposeful action as Miss Julie. She has enough of the serf in her to find the prospect of an honourable suicide painful and so, in the end, her death, like her life, must be performed as an act rather than executed as an action. Jean must deploy his histrionic abilities, perfected at the theatre, in order to impersonate the aristocratic voice that nerves the serf-like Julie for her self-destruction. In the Strindbergian world, all acts are gratuitous, motivation is a farce, and anyone who wishes to do must first learn not to think. The world of the play is filled with interpretations, yet nothing is certain for these people, who feel oppressed rather than enlightened by the sheer volume of information available.

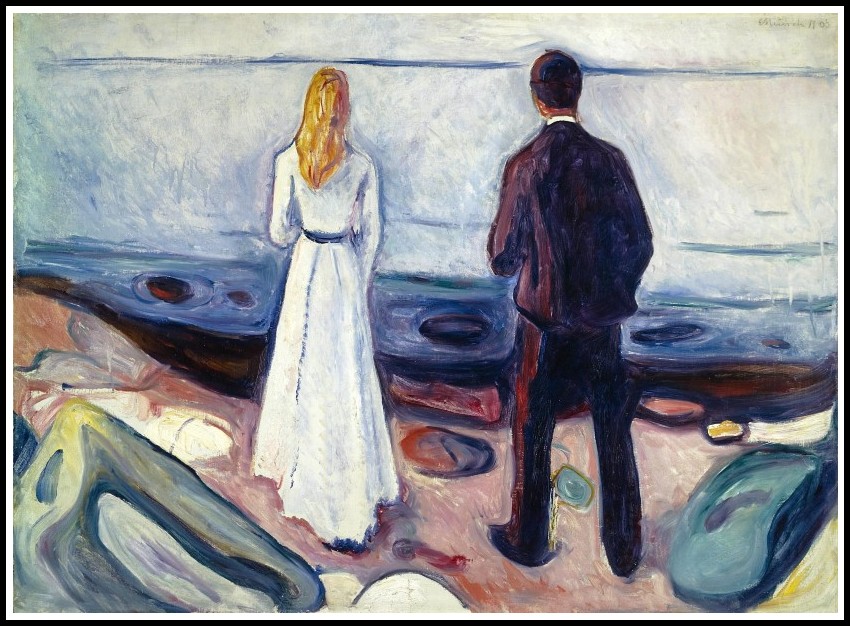

Edvard Munch, Two Human Beings – The Lonely Ones, 1905

DECLAN KIBERD: THREE BOOKS

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO GO TO A DESCRIPTION OF THE BOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ — READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments