Aribert Reimann

Ollea, Four Songs for Solo Voice on Poems by Heinrich Heine

ARIBERT REIMANN’S ‘OLLEA’: INTERVIEW EXTRACT WITH SOPRANO MOJCA ERDMANN

From Le Soir (Belgiuim), 30 March 2011. This excerpt translated from the French by Richard Jonathan.

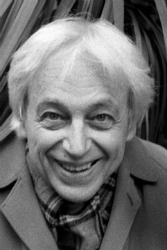

Mojca Erdmann | Photo: Felix Broede

What did your experience as a violinist contribute to your singing?

For a singer, phrasing and breathing are fundamental, just as for a violinist they are the foundation of good technique. And then there’s control—absolutely essential—of intonation, which is common to the two disciplines. I learned to play the violin only to be able to work in an orchestra, because my parents felt that alongside singing lessons—which could lead to an exciting but uncertain future—it would be advisable to learn a stable profession.

What is your relationship to contemporary music?

For me it’s a music like any other. It’s never been something apart. What’s important is that the composer know particular voices. I’ve just sung in the first production of Rihm’s Dionysos. He knows my voice well and his music integrates it perfectly.

Mojca Erdmann | Photo: Felix Broede

Mojca Erdmann, Staatsoper Berlin, March 2019

In Antwerp, your recital began with Debussy. That’s rather unusual.

Yes, but with melodies of a rare delicacy, melodies full of colour, before shifting into Mozart’s limpidity. Things get more complicated afterwards when Schumann takes up Goethe’s Mignon and Richard Strauss Shakespeare’s Ophelia. And then I finish with Heine—Ollea—a solo sequence of twelve minutes written in 2006 by Aribert Reimann, who wrote so well for Fassbaender and Fischer-Dieskau. He knows the voice better than anyone.

ARIBERT REIMANN & MOJA ERDMANN TRANSPOSED TO MATTEO & MARA IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Seven Chapter 2

̶ Put it in the player.

I take the cassette out of its case and slip it into the slot.

̶̶ It lasts exactly thirteen minutes.

̶ What is it?

̶ We’ll talk about it afterwards.

You press ‘play’.

̶̶ Don’t say another word!

Silence. And then it comes, the sense beyond signification, the singular voice threading its mystery through me. How, Marietta, could I ever convey the ravishment I experienced in those thirteen minutes? The voluptuous fusion of language and body, the festive return to a primordial state—how? Music alone can fetch a world from beyond meaning; only song itself can communicate the incommunicable. In those thirteen minutes, the ecstatic performance by an unaccompanied soprano of four electrifying songs shivered my spine and shook my bones.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1973

Simon Hantaï, Blanc, 1974

Listen! Intricate melismas, awkward intervals; sublime tone, perfect pitch: Along the full range of her tessitura, the soprano places the syllables of her idiomatic song. Subtlety of nuance vies with intensity of expression, full-throated glory with elusive transparency. Expressing a dark and passionate vehemence, she varies the pressure as she moulds the vowels; evoking an other-worldly dreaminess, she drains her voice of all vibrato: I hear the scream of the butterfly.

Listen! Floating a pure, ringing tone, she soars to a radiant high; in brilliant dark timbre, she marks the subterranean movement of a line. Speech-song or cantabile, vocalise or outcry, beyond vocal effects, the colouristic expression of pitches gives sense to the sound. Between attack and extinction, what artistry in sustaining tension!

Simon Hantaï, Blanc, 1973

Simon Hantaï, Untitled (folded canvas), 1971

Listen! The sober gravity of incisive articulation, the compelling beauty of a long-breathed line; the beguiling movement across a span of pitches, the furtive emergence of muted vowels. Operatic in its breadth of register, dramatic in its large intervallic leaps—What is this masterpiece?

Listen! Glissando connections and glottal attacks, a shimmer of rich overtones; the exhilaration of continuous vocalization, the sadness of decay between notes. Essence of music, purest of instruments, the voice as miracle: What immediacy, what intimacy, what bodily presence! When the final tone dies it is I who am breathless.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, n.d.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1973

̶ My God, Marietta! What was that?

̶ That, Sprague, was written by Matteo. Four songs for solo soprano, sung by a singer called Mara Zizek.

̶ Blow me away! It’s brilliant!

̶ Yeah.

̶ Matteo’s done it! This work will make his name! And who is Mara Zizek?

̶ She’s from Yugoslavia. Lives in Vienna.

Opening the window, I gulp the cold air.

̶̶ That was amazing! I’m stunned by the beauty of it!

̶ So am I. I was so moved during the recording I cried.

̶ You were there?

̶ Yes. In Matteo’s home studio. Just two days ago.

̶ Tell me about it!

And thus you came to conjure a woman who could have been your twin, standing before a microphone in a converted carriage house. I imagined the compressors, equalizers and mixers, the monitors and the reel-to-reel; I imagined the acoustic panels and bass traps, the condenser mic and filtered lights. But clearest in my mind was the image of a Slavic blonde in a Stones T-shirt, singing through a nylon stocking into the microphone.

̶ She’s from Ljubljana.

̶ Slovenia?

̶ Yes. She also plays the saxophone.

̶ That explains her long breath!

̶ It does. And her ear—that incredible ear!—she attributes to her years of playing the violin.

̶ The mastery of specific and indeterminate pitches?

You nod your head in assent.

̶ She moved me, Sprague. From the roots of my hair to the tips of my toes, she moved me!

Astounded by the persistence of sound, we remain silent: The evanescent has decided to stay.

Simon Hantaï, Study, 1971

Simon Hantaï, Composition, 1973

̶ And what are the words?

̶ You’ll never guess!

̶ Rilke, Ingeborg Bachmann?

̶ No, it’s Giacomo Leopardi, translated into German!

̶ What?

̶ Yes, believe it or not, it’s Leopardi. Take a look, in the blue notebook.

Seit ich dich erblickte,

welche ernsthafte Sorge hatte nicht dich

zum Gegenstande?

Since I first saw you,

of what deep concern of mine

were you not the ultimate object?

̶ Why in German, why didn’t Matteo keep the Italian?

̶ Can you imagine these songs in Italian?

̶ No, I can’t. Italian is bel canto.

̶ Exactly. Ironic distance, that’s what Matteo was after, and only by setting Leopardi in German was he was able to obtain it.

̶ It works beautifully. It’s unmistakably contemporary.

̶ Yes, but still has a subliminal link to the lieder tradition. That’s what he wanted.

̶ Well, he’s succeeded brilliantly!

Flesh made grace, at once

Body and spirit; air made intimate,

At once ethereal and real:

Mara, how you move me!

̶ Yes, and it’s all the more impressive because writing instrumentally for the voice is notoriously difficult. Mara says many composers make you hoarse after half an hour.

̶ Really? That’s unforgivable. You can’t replace a vocal cord like a violin string.

̶ Indeed. No danger of that with Matteo, though. His mother’s a singing teacher. He grew up with song.

̶ I remember him telling me that.

̶ And because he’s also an accompanist, no matter how far he pushes the envelope as a composer, he never loses that wonderfully supple sense of song…

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1960

Simon Hantaï, Mariale MC5, 1962

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

Naked, the voice lays bare the soul as the naked body cannot. Listen! The poem conveys a feeling of life ebbing from the body, but the voice refuses the facility of illustration. Instead, as the singer moulds the air in her mouth, she gives it a cold, silvery shimmer. Taking the vampire by the hand, she adopts a stance of distance: Love is colder than death, and it’s not effusion of feeling that can capture that.

Listen! From her diaphragm, through the modulating chamber of her mouth, comes a perfection of pitch, a purity of tone, that derive from the indifferent stars. And yet, despite that starry distance, the singer is bodily and spiritually present. In her voice I feel her singularity: Its overtones are echoes from her past; its relief, the terrain of her experience. Penetrating her receptivity, I am an arabesque of breath; caressing the hollows of her body, I am the air she spins and expels. Her voice is not a promise, her voice is not a lure: It is the pure presence of her being.

Simon Hantaï, Mariale MD 4, 1962

Simon Hantaï, Painting, 1963-64

Listen! Now she’s repeatedly attacking the same syllables, she’s undermining naïveté. And thus once again she takes a detour to gain access: Her voice is a diamond that doesn’t blind with its sparkle, but shines with an inner light: The more I lay myself open to that light, the more present I am to myself; the more present I am to myself, the more I admire you. Silence. We rise to our feet together with all in the concert hall. In bestowing this lavish applause, to whom am I really giving thanks and praise?

OLLEA, FOUR SONGS FOR SOLO VOICE ON POEMS BY HEINRICH HEINE

English translations by Richard Jonathan

Sehnsüchtelei

In dem Traum siehst du die stillen

Fabelhaften Blumen prangen;

Und mit Sehnsucht und Verlangen

Ihre Düfte dich erfüllen.

Doch von diesen Blumen scheidet

Dich ein Abgrund tief und schaurig,

Und dein Herz wird endlich traurig,

Und es blutet und es leidet.

Wie sie locken, wie sie schimmern!

Ach, wie komm ich da hinüber?

Meister Hämmerling, mein Lieber,

Kannst du mir die Brücke zimmern?

Nostalgia

Silent in a dream flowers

Shine fabulously before you;

With desire and nostalgia

Their scent overwhelms you.

But from these flowers an abyss

Deep and daunting separates you,

And your heart sinks into sadness,

And breaks and starts to bleed.

How they entice me, how they shimmer!

Oh, how can I cross the chasm?

Twin of Hypnos, can you help me?

Can you build me a bridge?

Odilon Redon, Bouquet, n.d.

Edvard Munch, Vampire, 1895

Helena

Du hast mich beschworen aus dem Grab

Durch deinen Zauberwillen,

Belebtest mich mit Wollustglut –

Jetzt kannst du die Glut nicht stillen.

Preß deinen Mund an meinen Mund,

Der Menschen Odem ist göttlich!

Ich trinke deine Seele aus,

Die Toten sind unersättlich.

Helena

With your magic you have called me forth

From out of my grave,

Inflamed my senses with desire—

And now the fire you cannot quell.

Press your lips to my lips,

I’ll drink up your very soul;

Mortal breath is divine,

And the dead insatiable!

Winter

Die Kälte kann wahrlich brennen

Wie Feuer. Die Menschenkinder

Im Schneegestöber rennen

Und laufen immer geschwinder.

O, bittre Winterhärte!

Die Nasen sind erfroren,

Und die Klavierkonzerte

Zerreißen uns die Ohren.

Weit besser ist es im Summer,

Da kann ich im Walde spazieren,

Allein mit meinem Kummer,

Und Liebeslieder skandieren.

Winter

The cold can truly burn

Like fire. Children

Scurry in the snowstorm,

Running ever faster.

Oh, bitter winter harshness!

Noses are frozen,

And the piano’s notes

Grate on our nerves.

Much better it is in summer!

Then can I walk in the forest,

Love-sick and alone,

And softly sing love songs.

Ellen Axson Wilson, Winter Landscape, c. 1911-12

Edvard Munch, Starry Night, 1922-24

Kluge Sterne

Die Blumen erreicht der Fuß so leicht,

Auch werden zertreten die meisten;

Man geht vorbei und tritt entzwei

Die blöden wie die dreisten.

Die Perlen ruhn in Meerestruhn,

Doch weiß man sie aufzuspüren;

Man bohrt ein Loch und spannt sie ins Joch,

Ins Joch von seidenen Schnüren.

Die Sterne sind klug, sie halten mit Fug

Von unserer Erde sich ferne;

Am Himmelszelt, als Lichter der Welt,

Stehn ewig sicher die Sterne.

Intelligent Stars

Flowers are rarely out of the foot’s reach,

Most will be trampled upon;

One passes by and flowers die,

The dull as well as the daring.

Pearls dwell beneath the waves,

But we know how to find them;

Holes are bored and they’re strung on a thread,

A fine yoke of silken cord.

Stars are more intelligent, they keep their distance

From our busy world;

In the vault of heaven, shining bright,

They stand aloof and eternal.

VIDEO: MOJCA ERDMANN SINGS & TALKS ABOUT MOZART

Interview with pianist Hélène Grimaud, featuring a performance by Mojca Erdmann

Mojca Erdmann: Interview about her album, Mostly Mozart (aka Mozart’s Garden)

SPOTIFY: ARIBERT REIMANN & MOJCA ERDMANN

Kuss Quartet & Mojca Erdmann, Brahms

Aribert Reimann, Ollea, Mojca Erdmann

Mojca Erdmann, Mostly Mozart

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

ARIBERT REIMANN: TWO GUARDIAN ARTICLES & A SCHOTT PROFILE

Click on the image to go to the corresponding article

REIMANN’S ‘OLLEA’ IN LIGHT OF NIETZSCHE’S CONCEPTION OF MUSIC

Four excerpts from Kathleen Higgins, ‘Nietzsche on Music’

INTRODUCTION TO THESE EXCERPTS: The paradox of ‘Ollea’—as demonstrated so convincingly in Mojca Erdmann’s performance—is that, with no instrument but the voice, it transforms words (poetic, yet retaining a good deal of discursivity) into music: pure, ‘absolute’ music, without a trace of verbal illustration. This fact can be fruitfully considered in light of Nietzsche’s conception of music. — R.J. / MM

From Kathleen Higgins, ‘Nietzsche on Music’. Journal of the History of Ideas, Vol. 47, No. 4 (Oct-Dec 1986), pp. 663-672. Available on JSTOR.

Words do violence to the immediacy and individuality of human experience. Words can refer only to those aspects of experience that have been made conscious, and ‘all becoming conscious involves a great and thorough corruption, falsification, reduction to superficialities and generalization. Ultimately, the growth of consciousness becomes a danger’ (Nietzsche, The Gay Science, Section 354). Nietzsche’s symbol of the Dionysian orgy calls attention to our preverbal sense that we share the ground of our experience with each other. Our language, however, though it depends on this sense, does not communicate the Dionysian awareness that we share our world directly. Language, in fact, would cease to function if we ceased to sustain this awareness; and no further use of language would suffice in that instance to restore the Dionysian awareness that is a precondition for its power. Music, however, could restore Dionysian awareness. Music not only reflects the fact that all our bodies respond to auditory sensation in essentially the same way; music also has the capacity to transmit a mode of awareness to its listeners. Specifically, it has the power to communicate the Dionysian sense that fundamentally existence—all that is entailed by ‘being alive’—is something that the listener can share with others.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1963

Simon Hantaï, Composition, 1958

In Schopenhauer’s view, music has the potential to affect the listener more powerfully than any other art is able to affect its beholder. This is so because the intended effect of any art is to release the observer from the grip of the illusory phenomenal world by making him aware of the reality behind it. But while other arts attempt to depict individual things and thus stimulate knowledge of the Platonic Ideas, music bypasses any possible reference to the phenomenal world and appeals to the will directly. Schopenhauer: ‘Music does not express this or that particular and definite pleasure, this or that affliction, pain, sorrow, horror, gaiety, merriment, or peace of mind, but joy, pain, sorrow, horror, gaiety, merriment, peace of mind themselves, to a certain extent in the abstract, their essential nature, without any accessories, and so also without the motives for them (The World as Will and Representation). The emotional effect of music cannot, therefore, derive from music’s representation of the individual aspects of existence. On the contrary, Schopenhauer argues, music has such a powerful effect on human beings because it directly represents the universal basis of human experience, the will.

Nietzsche follows Schopenhauer’s analysis to the extent that he believes that music expresses the nature of the world as a whole in its operations, rather than expressing particular experiences understood from an individual perspective. Nietzsche goes far beyond Schopenhauer, however, in his assessment of music’s salvational powers: ‘In music the passions enjoy themselves,’ Nietzsche’s aphorisms proclaim in Beyond Good and Evil, and elsewhere he remarks that, ‘Life without music is simply a mistake, a hardship, an exile.’ And these panegyrics to music are anticipated in The Birth of Tragedy, where Nietzsche argues that music alone can invest myths with the power to convey the Dionysian wisdom that, despite suffering, individual existence is joyous and powerful because it is grounded in the basic unity of all that lives. That is why the myths represented by Greek tragedies required music in order to achieve their full effect, for the words expressing the mythic tales provided only a surface image of the universal, Dionysian truths that the music expressed far more directly. Music is closer to the source of Dionysian insight than words, for music ‘speaks’ from ‘the heart of the world’.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1958

Simon Hantaï, Composition, 1951

Music, on Nietzsche’s analysis, directly expresses the ground of being that underlies all existence. Language is capable of expressing meaning only because words are conventionally established for the purpose of representing things; but music expresses the Dionysian basis of human reality without the mediation of vocabularies established by convention. This implies that elements of music do not, in principle, mean specific things in the way that words do, and that as a consequence music lacks the particular referential power of words, but Nietzsche does not regard this as an indication of a lack of power on the part of music. On the contrary, music ‘means’ in the sense that it conveys to its listeners the experience of being a part of the entire matrix of terrestrial living, an experience which occasions delight. This is not ‘meaning’ in the sense in which we normally say that language ‘means’, but Nietzsche contends that the sense of membership in a larger world, as it is directly transmitted to the listener in music, is actually a fundamental element involved in all linguistic meaning, though an element that we simply assume preconsciously. The power of words to reflect differences amongst the elements of the world presupposes an unstated awareness on the part of language-users that the world is already a unity. In experiencing music as we do, we reveal the awareness that Nietzsche takes to be prerequisite to our use of language. What our experience of music involves, then, is something like the fulfillment of a transcendental precondition for the possibility of human language.