Karl Amadeus Hartmann

PAUL GRIFFITHS ON KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN’S ‘LAMENTO’

The following text is taken from the liner notes to the album Tief in der Nacht: Alban Berg, Karl Amadeus Hartmann (ECM New Series 2153).

Hartmann’s Lamento had to wait a while in its composer’s drawer, for this ‘cantata for soprano and piano’ of 1955 was made out of the solo passages in a 1936-7 score for soprano, choir and piano. Hartmann had dedicated the original choral work to the memory of Alban Berg, the recently deceased Viennese master, and the piece won honourable mention in Universal Edition’s annual Emil Hertzka competition of 1938. However, Hartmann’s reasons for revisiting old compositions were rather special, Lamento being one of many for which he had sought no outlet during the Nazi years, and which he then felt the need to revise once that period was over, while maintaining his music’s qualities of protest and mourning.

Karl Amadeus Hartmann | Bayerische StaatsBibliothek

Juliane Banse, soprano

He found, early on, a mirror for the Nazi disaster in the Thirty Years’ War of three centuries before, and looked to writers from that period to assist him: Grimmelshausen for an opera subject (Simplicius Simplicissimus) and Andreas Gryphius for texts for the choral work, whose title, ‘Friede Anno 48’, refers to the peace of 1648. The three poems that remain in the 1955 version outline a story of suffering, remembrance and hope, and altogether of fortitude that finds a correlate in the stamina demanded of the singer, who is often required to be emphatic in the upper register, with an effect of declamatory authority proper to a civic statement (though at times the declamation may quieten to a lullaby). Thereby suited in stance and expression to Hartmann’s programme, the poems also offered an occasion for neo-Baroque formality, whether in the creation of a recitative-plus-aria form for the first poem or in the broken arcs of counterpoint that arrive, not least as the work enters its final phase (at ‘Herr, es ist genug’) and seems to be asking for Bach’s blessing.

Hartmann thus calls on a distant past—or, rather, two pasts, those of Gryphius’s war-observant poetry and of Bach’s heavenward music—to help him find his present. That present, though, is bifurcated. With its incisive imagery in the piano, its vociferous yet intensely precise soprano and its constant inventive power, Lamento is a big piece, one that thoroughly engages the two formidable musicians who present it here. Juliane Banse is the kind of singer Hartmann must have imagined, one who can maintain ease, power and warmth under difficult circumstances, whose singing conveys at once authority and vulnerability, and whose musical experience runs from Bach to the present day. Aleksandar Madžar similarly brings out the depth of history and the immediacy of feeling written into this work. Yet these artists also convey the desperate silence from which the piece started, when, living through unspeakable times, its composer could only lay down strong shadows for the future.

Aleksandar Madžar, pianist | Photo: Daniel Haeker

GUY RICKARDS ON KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN DURING WWII

From Guy Rickards, Hindemith, Hartmann and Henze (London: Phaidon Press, 1995) pp. 101-09

Käthe Kollwitz, Death Seizes a Woman, 1934

Even before Hitler’s armies achieved their greatest victories surging far into Russia after breaking the Nazi–Soviet pact in 1941, Karl Amadeus Hartmann in Munich had reflected that war was ‘the greatest of all the crimes of tyranny’ and composed a Sinfonia tragica. In two slow, sombre movements, Hartmann constructed a powerfully eloquent lament for the continent that was being ripped apart. He was not writing from the splendid isolation of an ivory tower. The tyrannical regime that he hated was an ever-oppressive presence around him.

The Sinfonia tragica was dedicated to Paul Collaer, who had planned to give the opera, Des Simplicius Simplicissimus Jugend, its première at the end of May 1940, before the German occupation of Belgium prevented its realization. Collaer was also unable to perform the Sinfonia tragica, but did ensure its rehearsal before returning the score to Hartmann, together with some suggested alterations.

Käthe Kollwitz, Death, 1934–37

Käthe Kollwitz, Death Grabbing at a Group of Children, 1934

Hartmann’s personal conduct during the Nazi period as a whole is shrouded in mystery. His stance of internal emigration was a courageous act for a man with a young wife and family, but at no time was he inclined to abandon Nazified Munich. ‘I could never leave this city. She holds tightly to those who have made their names in her, even when she does not seem very accommodating,’ he wrote. There have been suggestions of greater involvement in opposition to the Nazis. Hans Moldenhauer, in his biography of Anton von Webern (1978), states in a footnote that at ‘a time when the tidal wave of political nationalism swept his native country, Karl Amadeus Hartmann was one of the first to profess a pacifist creed and to engage in underground resistance against the Hitler regime’. Moldenhauer was a friend of Hartmann’s and was the dedicatee of the composer’s final, unfinished work, Gesangsszene. Later in his book Moldenhauer goes further: ‘Hartmann was a man of buoyant temperament and great charm. Politically, he belonged to a small group of Germans who, from the beginning, had adamantly opposed the Hitler regime. He escaped military service by going into hiding for long periods of time, and with a few trusted friends he formed the nucleus of a resistance movement.’ Many Germans were executed for less, yet nowhere are these friends and activities recorded. In the post-Nazi period, such conduct should have elevated him to hero status. Yet Hartmann himself never advertised it, nor do his autobiographical writings make reference to any underground activity. In the paranoia of post-war Germany, the Western powers retained much of the Nazi administrative apparatus intact, especially in Bavaria. This might explain a later reticence on Hartmann’s part but his widow is categoric in her denial of any involvement by any member of the Hartmann family in underground resistance.

One possible explanation for this disparity may lie in several circumstantial facts that in isolation amount to little but when taken together could be construed as significant. Karl’s brother Richard had distributed leaflets against Hitler during the presidential campaign in 1932. On Hitler’s assumption of the chancellorship the following year he fled to Switzerland, where he remained until 1946. Karl himself never belonged to any political party, though his Socialist sympathies were not unknown. He was summoned on several occasions to attend medical examinations to determine his fitness for military service. Judicious use of tablets causing profuse perspiration was sufficient for a final verdict to be deferred until a local art-loving medical director confirmed and certificated Hartmann’s unfitness for duty. Hartmann managed to help a pianist friend, Martin Piper, to dodge the draft at another examination by administering a disgusting concoction of ‘boiled washing soap, cigars and cognac’. Small beer perhaps, but enough to cost him liberty, or life, if he had been caught. His bravery and dissidence were never in doubt.

Käthe Kollwitz, Woman with Dead Child, 1903

Käthe Kollwitz, Worker Woman with Sleeping Child, 1927

Hartmann’s decision to cut himself off from musical life in Germany was definitely an act of conscience and one that he sustained more consistently than any German artist. Cut off by his own decision from the mainstream, he went to study in 1942 with the semi-outlawed Anton von Webern, the former pupil and associate of Arnold Schoenberg and promulgator of Schoenberg’s revolutionary twelve-note method, which systematized atonality by use of the twelve notes within the octave arranged in rigid series. Schoenberg had fled to the United States in 1934 following the Nazi accession to power, followed in 1938 by his students and colleagues in Austria. This left Webern, a minor aristocrat and racially ‘pure’, as the sole remaining exponent of Viennese radicalism. The roots of this tradition lay ultimately in the music of Mahler, which as Hartmann noted in a letter to his wife, ‘Webern praised at every available opportunity’. As a matter of course Mahler’s Jewish origins had rendered his music unacceptable to the Nazis. Webern had far outstripped Schoenberg in his extreme application of ‘serial’ techniques to rhythm and instrumentation as well as melody and harmony. Webern’s music had been labelled as degenerate and banned, despite his strongly pro-right political affinities. If he was viewed as something of a totem by Hartmann it was for musical rather than political or ‘confrontational’ reasons.

Hartmann first consulted Webern—in 1941—by letter, asking whether Universal Edition in Vienna, who were Webern’s publishers, might take on his music. Nothing came of this, but Hartmann was sufficiently encouraged to travel to Maria-Enzersdorf near Vienna, where Webern lived, in order to study with him. Hartmann learned to be careful and keep his political differences with Webern apart from his musical studies, as well as separate from his respect and admiration for the man. In the same letter to his wife, Hartmann wrote, ‘I was largely to blame that the conversation repeatedly turned to politics. This was a mistake, because with my strong sympathies towards anarchism I discovered things that I would have preferred not to. The main thing was that he seriously held the view that all authority should be respected for the sake of good order, and that one should—no matter what the price—recognize the State in which one lives.’

Käthe Kollwitz, Pietà, 1903

Käthe Kollwitz, Hunger, 1924

Hartmann was of a very different cast as a composer and he learned much from Webern’s method, without adopting his methodology. Little of Webern’s direct influence is discernible in Hartmann’s later music, except perhaps negatively in the general avoidance of serial techniques. A few works, such as the Fourth Symphony (1948), do make use of themes with twelve-note properties, but Hartmann always remained at heart a composer working within traditional means, however freely interpreted. He recognized the nature of his debt to Webern in a later letter to his wife: ‘In the end you could say that not only did I learn a great deal about composing from Webern, but that due to him I also became a more orderly person.’ The tuition he received was in the form of extended analyses covering a wide range of music, including Beethoven piano sonatas, Reger string quartets and Webern’s own Variations for Piano of 1935-6. One particularly memorable session included an off-the-cuff exposition on Schoenberg’s early opera, Erwartung (‘Expectation’).

Some of Hartmann’s own scores were gone through, including Des Simplicius Simplicissimus Jugend and what he termed ‘my first symphony’. It is unclear which symphony this might be: Versuch eines Requiems would not be called a symphony for eight more years, so either the 1938 Symphony for string orchestra and soprano or that based on Zola’s L’Oeuvre could be meant. It is even possible that the work referred to is the Sinfonia tragica. Pupil and teacher did not always concur in their opinions of other composers’ stature. ‘Even as I heartily rejoice at his opinion of Reger I cannot agree with his appraisal of Bruckner. He does not believe that Bruckner has contributed to the development of music. Is Bruckner then so different from Mahler?’ This remark encapsulates the essential difference between pupil and teacher. Webern’s music sprang ultimately from a Mahlerian, high-romantic aesthetic, whereas Hartmann was preternaturally Brucknerian in orientation. The music of Anton Bruckner also linked Hartmann to Hindemith in spirit. The Icelandic composer Jon Thόrarinsson who studied at Yale between 1944 and 1947 recalled that, among ‘the composers of the Classic and Romantic period, Anton Bruckner was the one most often referred to by Hindemith. I believe he considered Bruckner, who at this time was practically unknown in America, to be the greatest symphonist after Beethoven.’

Käthe Kollwitz, Young Girl in the Lap of Death, 1934

Käthe Kollwitz, Call of Death, 1937

The period of study with Webern occurred during the composition of one of Hartmann’s largest projects up to that time, Sinfoniae dramaticae. It comprises a symphonic overture, originally entitled China kämpft (‘China’s Struggle’), three symphonic hymns and a suite for orchestra with reciter, Vita nova (‘New Life’). The entire set was completed in 1943 and Hartmann then turned to revising the Sinfonia tragica by incorporating Collaer’s suggested alterations into the first movement. He worried over the safety of his manuscripts as aerial bombardments were increasing in intensity and the prospect of invasion seemed now the only outcome to end the war. Accordingly, Hartmann collected the most valuable of his manuscripts, including the opera, string quartet and the recent large symphonic pieces and ‘placed my works in a case which was soldered and buried two metres deep in a mountain’. In 1944, the arrest of a close friend, Robert Havemann, prompted Hartmann into commencing a new symphony—his fourth—entitled Klagegesang (‘Hymn of Lamentation’). He subsequently subtitled the work ‘symphonic expressions’ as if unsure of its credentials as a symphony. Even more than with the Symphonic Fragments, Klagegesang caused Hartmann considerable difficulty to get right. The initial version appears to have been substantively complete by the following year, but Hartmann continued to work at it until 1947. Concurrently with the work on Klagegesang, Hartmann began to evolve another symphonic work, the Adagio for large orchestra which eventually became the second of his numbered symphonies. The roots of the Adagio lay in the Vita nova suite; whether his re-use of some of the material was occasioned by dissatisfaction with the earlier work can now only be guessed at.

Vita nova was lost (and part of it remains so), while the Sinfonia tragica was to disappear for over forty years en route to Belgium when Hartmann despatched it in 1946 to Collaer for the much-delayed première. In both works and life, wartime cast a shadow over Hartmann that took years to dispel.

Käthe Kollwitz, Self-Portrait, 1934

KARL AMADEUS HARTMANN’S ‘LAMENTO’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

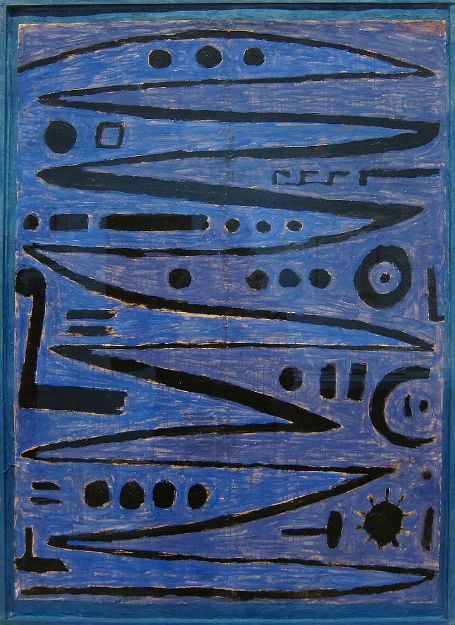

Paul Klee, Demonic Puppets, 1929

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

Down the keyboard a chromatic descent makes it clear that art is my home and exile my state: Love is but the madness that impels me from one to the other. Over the driving turbulence of the piano, over the staccato dissonance and the crashing chords, the voice of a survivor in a field of corpses comes to offer thanks. Now into silence the piano trills, breaking the singer into prayer. From the hollows within her body, a voice comes to plead for the living after the massacre. So this is the song you first heard at the Kluge’s house in Corfu, the song by a composer who moved you in that summer of ‘73. Perpetrator, victim, bystander? Mastering the art of inner emigration, from within Nazi Germany he bore witness, making a music of protest and mourning while living a life of resistance. And thus, in your discussions with Jürgen’s family, Hartmann offered an illustration of how resistance can surpass the human, all too human, trilogy.

Look at the singer: Her hair is exactly the same red as yours, the red of copper in the evening sun, the copper by which gods enter the ear drum. Does she remind you of Mara? She does me. Listen! Now fiercely tender, now declamatory, there’s depth and immediacy in her every phrase. How does she manage to combine such authority with vulnerability? Look at the pianist: The curl of his fingers, the relaxation of his wrist, as spider-like he spins out a soft, fluid legato—only to execute a violent, flat-fingered attack right after. I look at you and I am moved: The moist glow of your eyes tells me you’re thinking of Matteo. And thus, into this juxtaposition of the Third Reich and the Thirty Years War, into this song of suffering and remembrance, comes the death of a friend. Dark-hued, entreating, the singer’s voice captures your emotion.

Paul Klee, Any Kind of Cruelty, 1919

Paul Klee, Heroic Strokes of the Bow, 1935

Friede

Andreas Gryphius (1616-64)

Zeuch hin, betrübres Jahr, zeuch hin mit meinen Schmerzen,

Zeuch hin mit meiner Angst und überhäuftem Weh,

Zeuch so viel Leiden nach! Bedrängte Zeit, vergeh

Und führe mit dir weg die Last von diesem Herzen!

Herr, vor dem unser Jahr als ein Geschwätz und Scherzen,

Fällt meine Zeit nicht hin wie ein verschmelzter Schnee?

Lass doch, weil mir die Sonne gleich in der Mittagshöh,

Mich doch nicht untergehn gleich ausgebrannten Kerzen!

Nach Leiden, Leid und Ach und lent ergrimmten Nöten,

Nachdem auf uns gezückt und eingesteckt das Schwert

Indem der süsse Fried ins Vaterland eingekehrt,

Und man ein Danklied hört staff rasenden Trompeten.

Bisher sind wir tot gewesen, kann nun Fried ein Leben geben,

Ach, so lass uns, Friedenskönig, durch dich froh und friedlich leben,

Wo du Leben uns versprochen!

Herr, es Ist genug geschlagen

Angst und Ach genug getragen,

Gib doch nun etwas Frist, dass ich mich recht bedanke.

Gib, dass ich der Handvoll Jahre

Froh werde eins vor meiner Bahre,

Missgönne mir doch nicht dein liebliches Geschenke.

Herr, es Ist genug geschlagen

Angst und Ach genug getragen

Friede den Menschen

Friede den Toten

Friede den Lebenden

Friede, Friede, Friede

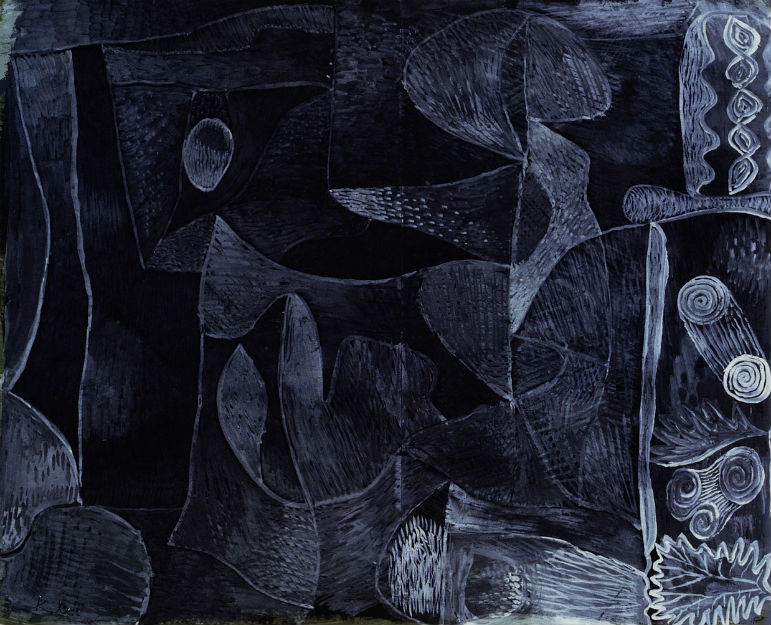

Paul Klee, Angel Applicant, 1939

Paul Klee, Morning Grey, 1932

Peace

Andreas Gryphius, tr. Paul Griffiths

Away, sad year, away with my despairing,

Away with dread, with overwhelming woe,

Away with so much sorrow; hard year, go,

And take the load my heart was bearing!

O Lord, for whom our year’s past caring,

Must my time now be up like melted snow?

O let me not at highest noontide grow

To imitate a candleflame’s last flaring!

From anguish, pain and need of utmost tearing,

From when the sword was waving to and fro,

Now here the breeze of peace begins to blow,

And songs of thanks replace the trumpet’s blaring.

We once were dead; now peace a life is giving,

So, king of peace and joy, let us be living

The life that you have promised!

Lord, I have borne enough,

I have been torn enough,

Allow me yet a little time for thought.

Give me a few years more

In which to count the score

Of gifts your love for me has bought.

Lord, I have borne enough

I have been torn enough

Peace to humanity

Peace to the dead

Peace to the living

Peace, peace, peace

Paul Klee, Walpurgisnacht, 1935