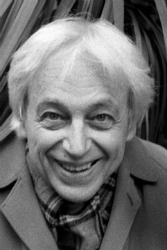

Wolfgang Rihm

Lichtzwang | Four Poems from ‘Atemwende’ by Paul Celan

SETTING WORDS TO MUSIC: WOLFGANG RIHM ON ‘LICHTZWANG’

POETIC TEXT AND MUSICAL CONTEXT

From ‘Texte poétique et contexte musical’ in Wolfgang Rihm, Fixer la liberté ? Écrits sur la musique (Geneva: Editions Contrechamps, 2014). This excerpt translated from the French by Richard Jonathan.

The ‘epic’ character of a piece of music does not necessarily consist in the representation of an action that one could communicate verbally but rather in the transposition of certain principles of the unfolding of verbal action towards techniques of musical development.

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2018

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2010–19

In Lichtzwang for solo violin and orchestra, the second part of an attempt at a portrait of Paul Celan conceived as a cycle, I deliberately bring out this epic element. I take as my point of departure the kernel of a single word, Lichtzwang (‘light compulsion’), the title of a poetry collection by Celan and the central poetic notion of one of the poems. It concerns someone who cannot ‘darken over towards’ someone else when, or because, there reigns a ‘light compulsion’. This occurs against the background of an imaginary eulogy for the dead that I, struck by the suicide of the poet, dared to term ‘in memoriam’.

This was all the more an attempt to work in the epic register in that I tried, via the writing, to integrate the tone of a lament (the musical topos) in the situation of a ‘being under light compulsion’ (the verbal image). Moreover, I tried to do so—having considered this incapacity to ‘darken over towards someone’—by imagining all that, in true obscurity, still opposes one who accepts ‘light compulsion’ and who, though suffering from it, nevertheless speaks from that state.

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2018–19

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2018–19

That is why the role is given to a solo violin that a collectivity (I did not use the violins of the orchestra) first opposes and almost impedes, but then participates in its breakdown via a commentary in the form of a eulogy for the dead. From the point of view of the musical discourse, the growing solitude of the poetic voice—its decomposition, after an ‘arrival of light’, into isolated and increasingly incommensurable sentences, words and syllables—is concretely perceptible at the end of the work.

The obsessional character of both the eulogy for the dead and the violin/solo voice will have overcome that which surrounds it thanks to song. It then falls into the dissolution, indicated by unisons on C, of all sonorous individuality. These two processes—subjective eulogy for the dead and increasing solitude—occur simultaneously, one within the other; their identities as ‘poetic text’ and ‘musical context’ disappear in an amalgam in the epic register. The idea of ‘disappearance of one in the other’ is also expressed by the mixing of two genres, the concert and the cantata.

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2009

Zong-De An, The Real, 2016

In Lichtzwang, text and music enter into a symbiotic relationship wherein music is indeed the external manifestation but it is the text that determines the internal life. This is probably one more proof of the impossibility of marrying music and text unless the two intertwine like arabesques around each other, forming a décor for one another, and the vibrations of their relationship become what we experience.

Note that, respecting the demands of plurivocity and univocity, vibrations always travel a two-way street: in one direction as sound, toward the exterior, and in the other direction as content, toward the interior. The boundaries fluctuate, yet we experience the transitions as ruptures because we lack the organ that can simultaneously apprehend an abstract conception as sensory experience and sensory experience as an abstract conception. And that is just fine. It means that it is we who remain in movement, it is we who—once music speaks to us or words move us—have to substitute for this impossible simultaneity a feeling of a distance travelled. In a word, it is we who, in linking the two, bring to life something new.

Zong-De An, Le Temps, 2008

SPOTIFY: WOLFGANG RIHM, IN DEN FLÜSSEN NÖRDLICH DER ZUKUNFT (ATEMWENDER I)

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

In den Flüssen nördlich der Zukunft

Paul Celan

In den Flüssen nördlich der Zukunft

werf ich das Netz aus, das du

zögerd beschwerst

mit von Steinen geschriebenen

Schatten.

In the rivers north of the future

Paul Celan, tr. R. Heinemann & B. Krajewski

In the rivers north of the future

I cast out the net, which you

hesitantly weight

with stone-written

shadows.

Wolfgang Rihm: Lieder | Richard Salter & Bernhard Wambach

WOLGANG RIHM WITH PAUL CELAN IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Neysa Grassi, Warm Spring Rain, 2017

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

Tossing off three arpeggios, the pianist tosses me into expectation: I am a fisherman, casting out the net which you have weighted with stones. Hesitating, you wondered whether one more stone would be one too many, one less one too few: You have found the right tension, for in the clear water my net is suspended (the shadows of the stones tell me so). There is nothing to do now but wait. Listen: The music makes no claim to grasp meaning, the voice pursues its own phantoms. Before it’s over, Marietta, tell me: Why are you leaving me? Haven’t we been good at managing the distance that makes intimacy possible? Haven’t we found the right tension, the tension that allows us—time and time again—to sparkle in our self-becoming? Oh set your stones again, my love, the river has not yet reached the sea; let me cast the net again, beyond what you and I can see: Do you no longer have faith in me?

SPOTIFY: WOLGANG RIHM, LICHTZWANG

You can listen to the track in full with a registered Spotify account, which comes for free.

Tianwa Yang, violin

Wolfgang Rihm: Lichtzwang

Paul Celan

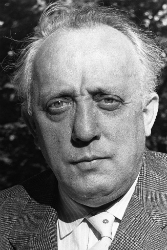

PAUL CELAN: LICHTZWANG

Translated by Michael Hamburger

From Poems of Paul Celan, translated by Michael Hamburger (NY: Persea Books, 1995) pp. 294-323

HÖRRESTE, SEHRESTE, im

Schlafsaal eintausendundeins,

tagnächtlich

die Bären-Polka:

sie schulen dich um,

du wirst wieder er.

SCRAPS OF HEARD, OF THINGS SEEN, in

Ward a thousand and one,

day-nightly

the Bear Polka:

you’re being re-educated

they’ll turn you back into he.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Scratch, 2012

Hideaki Yamanobe, Untitled, 2018

IHN RITT DIE NACHT, er war zu sich gekommen,

der Waisenkittel war die Fahn,

kein Irrlauf mehr,

es ritt ihn grad —

Es ist, es ist, als stünden im Liguster die Orangen,

als hätt der so Gerittene nichts an

als seine

erste

muttermalige, ge-

heimnisgesprenkelte

Haut.

NIGHT RODE HIM, he had come to his senses,

the orphan’s tunic was his flag,

no more going astray,

it rode him straight —

It is, it is as though oranges hung in the privet,

as though the so-ridden had nothing on

but his

first

birth-marked, se

cret-speckled

skin.

MIT MIKROLITHEN gespickte

schenkend-verschenkte

Hände.

Das Gespräch, das sich spinnt

von Spitze zu Spitze,

angesengt von

sprühender Brandluft.

Ein Zeichen

kämmt es zusammen

zur Antwort auf eine

griibelnde Felskunst.

HANDS

giving – given away,

larded with microliths.

The conversation that’s spun

from peak to peak,

scorched by

spume air from a fire.

A sign

combs it together

in reply to a

brain-racking rock art.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Scratch 2, 2018

Hideaki Yamanobe, Klangass. Ton Nr. 38, 2008

WE WERE LYING

deep in the macchia, by the time

you crept up at last.

But we could not

darken over to you:

light compulsion

reigned.

WIR LAGEN

schon tief in der Macchia, als du

endlich herankrochst.

Doch konnten wir nicht

hinüberdunkeln zu dir:

es herrschte

Lichtzwang.

WAS UNS

zusammenwarf, schrickt auseinander,

ein Weltstein, sonnenfern,

summt.

THAT WHICH

threw us together

startles apart,

a world-boulder, sun-remote,

hums.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Summer Night I, 2018

Hideaki Yamanobe, Daylight White 2, 2018

BEI BRANCUSI, ZU ZWEIT

Wenn dieser Steine einer

verlauten ließe,

was ihn verschweigt:

hier, nahebei,

am Humpelstock dieses Alten,

tät es sich auf, als Wunde,

in die du zu tauchen hättst,

einsam,

fern meinem Schrei, dem schon mit-

behauenen, weißen.

AT BRANCUSI’S, THE TWO OF US

If one of these stones

were to give away

what it is that keeps silent about it:

here, nearby,

at this old man’s limping stick,

it would open up, as a wound,

in which you would have to submerge,

lonely,

far from my scream, that is

chiselled already, white.

TODTNAUBERG

Arnika, Augentrost, der

Trunk aus dem Brunnen mit dem

Sternwürfel drauf,

in der

Hutte,

die in das Buch

– wessen Namen nahms auf

vor dem meinen? –,

die in dies Buch

geschriebene Zeile von

einer Hoffnung, heute,

auf eines Denkenden

kommendes

Wort

im Herzen,

Waldwasen, uneingeebnet,

Orchis und Orchis, einzeln,

Krudes, später, im Fahren,

deutlich,

der uns fährt, der Mensch,

der’s mit anhört,

die halb-

beschrittenen Knüppel-

pfade im Hochmoor,

Feuchtes, viel.

JETZT, da die Betschemel brennen,

eß ich das Buch

mit allen

Insignien.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Klangassoziationen Szene R 10/12, 2002

Hideaki Yamanobe, Scratch Flowing 3, 2010

TODTNAUBERG

Arnica, eyebright, the

draft from the well with the

star-crowned die above it,

in the

hut,

the line

– whose name did the book register before mine? –,

the line inscribed

in that book about

a hope, today,

of a thinking man’s

coming

word

in the heart,

woodland sward, unlevelled,

orchid and orchid, single,

coarse stuff, later, clear

in passing,

he who drives us, the man,

who listens in,

the half-

trodden fascine

walks over the high moors,

dampness, much.

Now that the hassocks are burning

I eat the book

with all its

insignia.

EINEM BRUDER IN ASIEN

Die selbstverkliirten

Geschütze

fahren gen Himmel,

zehn

Bomber gähnen,

ein Schnellfeuer blüht,

so gewiß wie der Frieden,

eine Handvoll Reis

erstirbt ais dein Freund.

FOR A BROTHER IN ASIA

The self-transfigured

guns

ascend to heaven,

ten

bombers yawn,

a quick-firing flowers,

certain as peace,

a handful of rice

unto death remains your true friend.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Scratch 08-4, 2008

Hideaki Yamanobe, Sunday ‘Memo: 02w-10 Daylight’, 2003

WIE DU dich ausstirbst in mir:

noch im letzten

zerschlissenen

Knoten Atems

steckst du mit einem

Splitter

Leben.

HOW YOU die out in me:

down to the last

worn-out

knot of breath

you’re there, with a

splinter

of life.

HIGHGATE

Es geht ein Engel durch die Stube –:

du, dem unaufgeschlagenen Buch nah,

sprichst mich

wiederum los.

Zweimal findet das Heidekraut Nahrung.

Zweimal erblalßts.

HIGHGATE

An angel has walked through the room –:

you, near the unopened book,

acquit

me once more.

Twice the heather finds nourishment.

Twice it fades.

Hideaki Yamanobe, Klangassoziationen Szene V 6/12, 2014

Hideaki Yamanobe, Landscape 08-01, 2008

ICH KANN DICH NOCH SEHN: ein Echo,

ertastbar mit Fühl-

wörtern, am Abschieds-

grat.

Dein Gesicht scheut leise,

wenn es auf einmal

lampenhaft hell wird

in mir, an der Stelle,

wo man am schmerzlichsten Nie sagt.

I CAN STILL SEE YOU: an echo

that can be groped towards with antenna

words, on the ridge of

parting.

Your face quietly shies

when suddenly

there is lamplike brightness

inside me, just at the point

where most painfully one says, never.

DIE EWIGKEITEN fuhren

ihm ins Gesicht und drüber

hinaus,

langsam löschte ein Brand

alles Gekerzte,

ein Grün, nicht von hier,

umflaumte das Kinn

des Steins, den die Waisen

begruben und wieder

begruben.

THE ETERNITIES struck

at his face and

past it,

slowly a conflagration extinguished

all candled things,

a green, not of this place,

with down covered the chin

of the rock which the orphans

buried and

buried again.

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 9, 1999

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 8, 2015

DIE IRIN, die abschiedsgefleckte,

behest deine Hand,

schneller als

schnell.

Ihrer Blicke Bläue durchwächst sie,

Verlust und Gewinn

in einem:

du,

augenfingrige

Ferne.

THE IRISHWOMAN, mottled with parting,

reads in your hand,

faster than

fast.

The blue of her glances grows through her,

loss and gain

in one:

you,

eye-fingered

farness.

KEIN HALBHOLZ mehr, hier,

in den Gipfelhängen,

kein mit-

sprechender

Thymian.

Grenzschnee und sein

die Pfähle und deren

Wegweiser-Schatten

aushorchender, tot-

sagender

Duft.

NO MORE HALF-WOOD, here,

on the summit slopes,

no col-

loquial

thyme.

Border snow and

its odour that

auscultates the posts

and their road-sign shadows,

declaring them

dead.

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 2, 2015

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 6, 2015

ORANIENSTRASSE 1

Mir wuchs Zinn in die Hand,

ich wulßte mir nicht

zu helfen:

modeln mochte ich nicht,

lesen mocht es mich nicht –

Wenn sich jetzt

Ossietzkys letzte

Trinkschale fände,

liß ich das Zinn

von ihr lernen,

und das Heer der Pilger-

stabe

durchschwiege, durchstünde die Stunde.

ORANIENSTRASSE 1

Tin grew into my hand,

I did not know

what to do:

I had no wish to model,

it had no wish to read me –

If now

Ossietzky’s last

drinking cup were found

I should let the tin

learn from that,

and the host of pilgrim

staves

would stone-wall, withstand the hour.

BRUNNEN-

artig

ins Verwunschne getieft,

mit doppelt gewalmten

Tagträumen drüber,

Quader

ringe

urn jeden Hauch:

die Kammer, wo ich dich liß, hockend,

dich zu behalten,

das Herz befehligt

den uns leise bestrickenden Frost

an den geschiedenen

Fronten,

du wirst keine Blume sein

auf Urnenfeldern

und mich, den Schriftträger, holt

kein Erz aus der runden

Holz-Lehm-Hütte, kein

Engel.

SUBMERGED

Well-

like into accursedness,

with doubly hipped

daydreams above,

ashlar

rings

around each breath:

the bedroom where I left you, crouching

so as to hold you,

the heart commands

the frost that gently captivates us

on the divided

fronts,

you will be no flower

on urn fields

and me, the script-bearer, no

ore releases from the round wood

and mud cabin, no

angel.

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 8, 2015

Elvire Ferle, Untitled 43, 2015

FAHLSTIMMIG, aus

der Tiefe geschunden:

kein Wort, kein Ding,

und beider einziger Name,

fallgerecht in dir,

fluggerecht in dir,

wunder Gewinn

einer Welt.

FALLOW-VOICED, lashed

forth from the depth:

no word, no thing,

and either’s unique name,

primed in you for falling,

primed in you for flying,

sore gain

of a world.

SPERRIGES MORGEN

ich beiße mich in dich, ich schweige mich an dich,

wir tönen,

allein,

pastos

vertropfen die Ewigkeitsklänge,

durchquäkt

von heutigem

Gestern,

wir fahren,

groß

nimmt uns der letzte

Schallbecher auf:

den beschleunigten Herzschritt

draußen

im Raum,

bei ihr, der Erd-

achse.

OBSTRUCTIVE TOMORROW

I bite my way into you, my silence nestles into you,

we sound,

alone,

pastily

eternity’s tones drip away,

croaked through by

the hodiernal

yesterday,

we travel,

largely

the last of the sonic bowls

receives us:

the boosted heart pace

outside

in space,

brought home to the axis

of Earth.

Albert Llobet Portel, Broken Lines II, 2013

John Richard Fox, Untitled 7902, 1979

STREU OCKER in meine Augen:

du lebst nicht

mehr drin,

spar

mit Grab

beigaben, spar,

schreite die Steinreihen ab,

auf den Händen,

mit ihrem Traum

streich über die

ausgemünzte

Schlifenbeinschuppe,

an der

großen

Gabelung er-

zahl dich dem Ocker

dreimal, neunmal.

SPRINKLE OCHRE into my eyes:

no longer

you live in them,

be sparing,

of graveside

supplements, be sparing,

walk up and down the stone rows

on your hands,

with their dream

graze the debased coinage,

the scale of

my temporal bone,

at the

great

road fork tell

yourself to the ochre

three times, nine times.

SCHALTJAHRHUNDERTE, Schalt-

sekunden, Schalt-

geburten, novembernd, Schalt-

tode,

in Wabentrögen gespeichert,

bits

on chips,

das Menoragedicht aus Berlin,

(Unasyliert, un-

archiviert, un-

umfürsorgt?

Am Leben?),

Lesestationen im Spätwort,

Sparflammenpunkte

am Himmel,

Kammlinien unter Beschuß,

Gefühle, frost-

gespindelt,

Kaltstart –

mit Hämoglobin.

LEAP-CENTURIES, leap-

seconds, leap-

births, novembering, leap-

deaths,

stacked in honeycomb troughs,

“bits

on chips”,

the menorah poem from Berlin,

(Unasylumed, un-

archived, un-

welfare-attended? A

-live?),

reading stations in the late word,

saving flame points

in the sky,

comb lines under fire,

feelings, frost-

mandrelled,

cold start –

with haemoglobin.

John Richard Fox, Untitled 7601, 1976

John Richard Fox, Untitled 7801, 1978

WIRK NICHT VORAUS,

sende nicht aus,

steh

herein:

durchgründet vom Nichts,

ledig allen

Gebets,

feinfügig, nach

der Vor-Schrift,

unüberholbar,

nehm ich dich auf,

statt aller

Ruhe.

DO NOT WORK AHEAD,

do not send forth,

stand

into it, enter:

transfounded by nothingness,

unburdened of all

prayer,

microstructured in heeding

the pre-script,

unovertakable,

I make you at home,

instead of all

rest.

VIDEO: WOLFGANG RIHM – 3 PIECES, 3 GENRES

Wolfgang Rihm: Klavierstück n°5 | Bertrand Chamayou, piano

Gesänge for voice and piano op. 1 | Johanna Vargas, soprano & Magdalena Cerezo, piano

Wolfgang Rihm: Gejagte Form (excerpt) | Ensemble intercontemporain