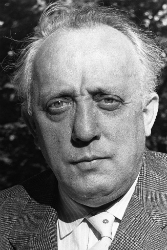

Ligeti

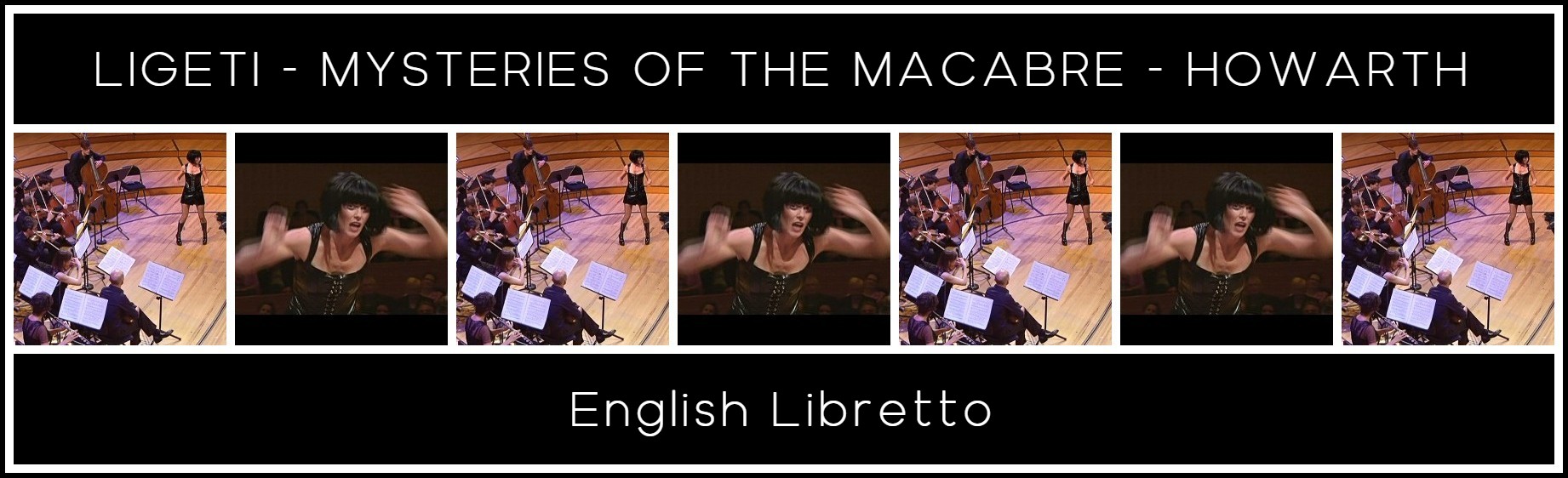

Mysteries of the Macabre: English Libretto | Le Grand Macabre: Synopsis & Analysis

BARBARA HANNIGAN – MAHLER CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

Ligeti

MYSTERIES OF THE MACABRE

English Libretto

Transcribed from the subtitles of Barbara Hannigan’s performance of the piece with the Mahler Chamber Orchestra on the DVD ‘Barbara Hannigan: Concert & Documentary’ (Accentus Music, 2015).

Note: The words in italics are uttered by members of the orchestra.

‘Mysteries of the Macabre’ is an arrangement of three coloratura arias from Le Grand Macabre reduced for chamber ensemble by Elgar Howarth.

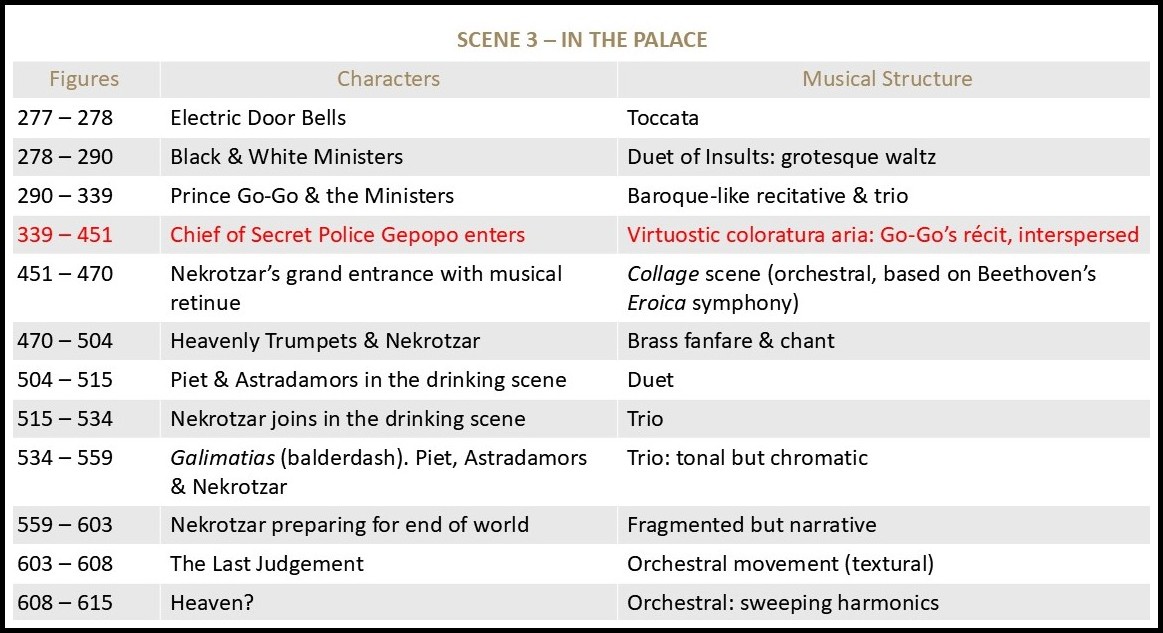

See the Synoptic Chart below to locate this sequence in the broader scheme of the opera, namely in Scene 3, Figures 339- 451.

Psst! Ps-psst! Ps-ps-psst! Shsht!

Co! Coco! Kho!

Cocococo! Cococo!

Cocoding zero!

O-O-O-O-O!

Aha!

Cococoding zero, zero:

Highest security grade!

Aha! Aha!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Ze-ro, zero!

Birds on the wing!

Ch-ch-ch-ch-ch!

Double-you-see!

Snakes in the grass!

Rabble, rabble, rabble!

Riot, riot!

Too too too too too!

Unlawful assemblies!

Cha cha cha cha cha!

Communal insurrection!

Mutinous masses!

Cha chee cho choo cha!

Turbulence! Panic!

Panic! Papapapa-panic!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Groundless! Groundless!

Phobia!

Wide of the mark!

Right off the track!

Hypopo

Hypopopopopopopata

Hypochondria!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Rrsh!

What – did you say?

Rsch!

March! March-t! March target!

Direction! Rection! Direction!

Prince! Your palace!

March-target royal palace!

Palace!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Password:

Gogogo-golash, go-golash!

Demonstrations, ha!

Protest-actions, ha!

Provocations, ha!

Psst!

Much discretion!

Close observation!

Take precautions!

That’s all!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Psst! Psst!

Not a squeak!

Confidential!

One more thing:

Bear in mind!

Silence is golden!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Secret cypher: Code-name: Loch Ness monster!

Comet in sight!

Red glow! Burns bright!

Chu chu chu chu chu

Psst! Sit tight! No fright!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Yes! No!

No! Yes! No!

Yes! Yes-No!

Beyond all doubt!

Satellite! Asteroid!

Planetoid! Polaroid!

Coming fast!

Hostile! Perfidious! Menacing!

Momentous! Fatal!

Stern measures! Stern measures! Stern measures?

Stern measures!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Kukuriku! Kikeriki! He’s coming!

Coming! Coming! Coming! Coming!

Kikerikeke! Kokorikoko!

Kukurikuku! Kakarikaka!

Ten!

Nine!

Eight!

Seven!

Brikamaka! Kamakabri! Makabri!

Six!

Five!

Four!

Three!

Two!

Makrabey! Makrabey!

One!

Zero!

Makrabey! Makrabey!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Coming! Coming! Look there!

There! There! There!

He’s getting in! He’s getting in! He’s getting in! He’s in!

Where’s the guard? Where’s the guard? The guard! The guard! The guard!

Call the guard! Call the guard!

Call the gua’! Call the Gua’!

Call ’e gau’! Call ’e gau’!

Call guarda!

Da! Da! Da!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Ada! Ada! Ada! Ada!

Da! Da! Da! Da!

Da! Da! Da!

Pssst!

Da!

György Ligeti, Mysteries of the Macabre, Barbara Hannigan & Mahler Chamber Orchestra

Mysteries of the Macabre

LIGETI IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Richard Jonathan

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

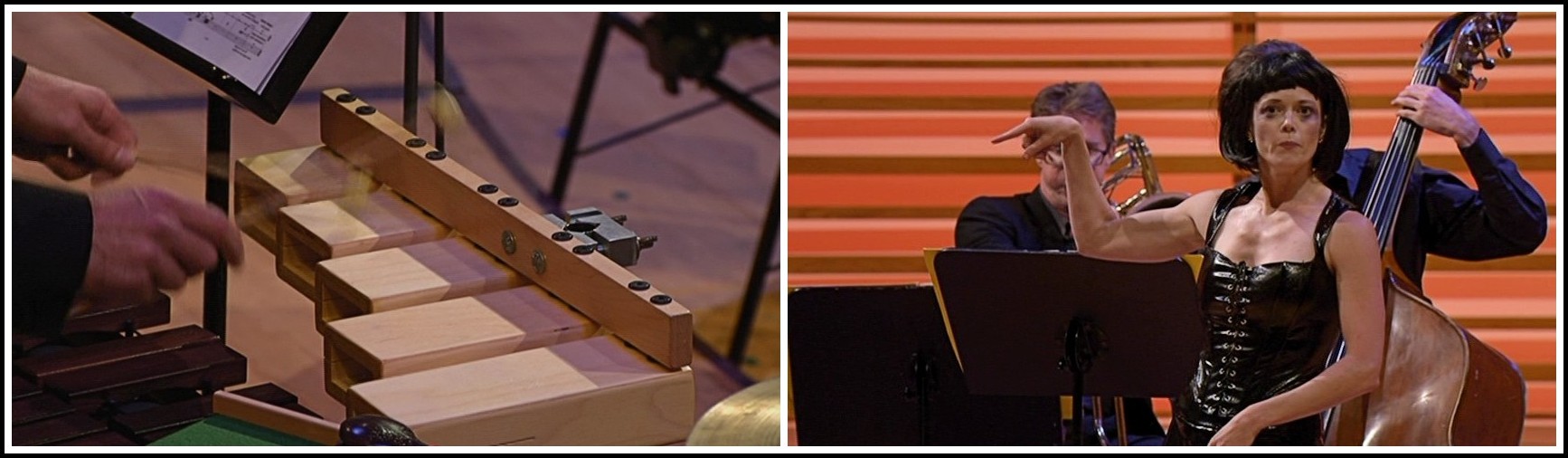

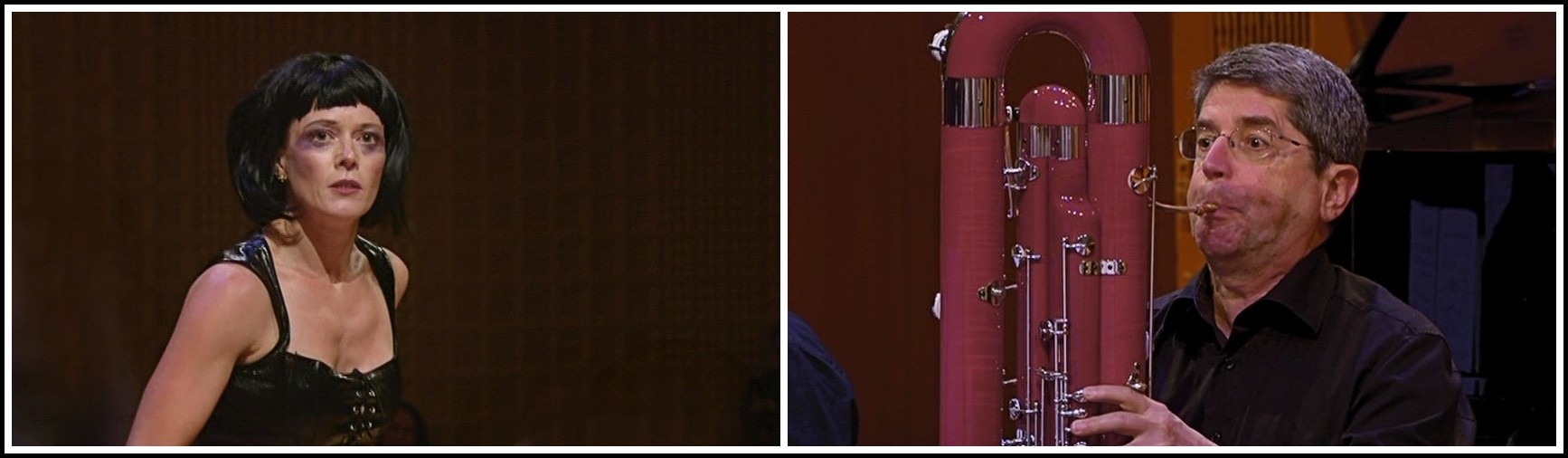

Bongos, maracas and castanets, glockenspiel, police whistle and tom-tom: Together with brass, strings and woodwinds, the percussion weaves a texture of hysteria that the soprano pierces with coloratura cries. Going from raucous gibberish to biting interjections, soaring flights to bird-like calls, she is desperately trying to make conductor and instrumentalists understand the urgency of what she’s reporting. The conductor doesn’t give a damn, the musicians rise in defiance. ‘Ja! Nein! Nein! Ja! Nein! Nein! Ja! Ja! Nein’: Is she a whore on heels, a chorus girl seeking a cancan? Is she Cassandra in an ecstatic trance or Oedipus back from the Oracle?

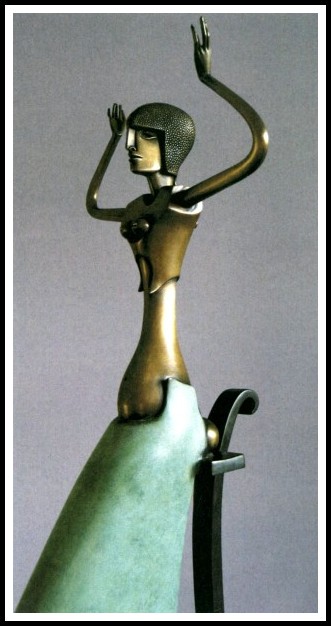

Paul Wunderlich, Eve with Serpent, 1997

‘Kakakakakakastrophe! Er kommt! Er kommt! Er kommt!’ Of what is she so afraid? In a tizzy of trepidation she reaches a paroxysm of panic; her hair flies out as her fear mounts: ‘Er ist schon da! Er ist schon da! Er ist schon da!’ Perhaps she’s an escapee from Pitié-Salpêtrière or a visionary of divine vengeance? Maybe she’s being ravished by an incubus, reliving the trauma of Red Riding Hood? No. She is Gepopo, chief of the secret police of Brueghelland and de facto angel of death: She has come to warn the Prince that the end of the world is at hand. And thus we relive Ligeti’s ironic take on the Requiem: The alienation induced by the grotesque is a means to overcome the fear of death.

Paul Wunderlich, The Questioner’s Wife, 2006

And we, Marietta, how do we accommodate the exterminating angel? Last night after we made love, when I said I would die for you, you said nobody can die in the place of another; when I said it’s an enormous responsibility, the irreplaceability of one’s death, you said that’s precisely why you feel guilty: You could never be responsible enough. Er! Er! Er! Er ist schon da! Schon da! Da! Da! Da! Da! Da! The Secret Police Chief finally ceases her hysteria; in a bubble of calm, the redhead recomposes herself as the applause thunders down.

Paul Wunderlich, Guardian Angel, 2006

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

Synopsis

LE GRAND MACABRE

György Ligeti

This text by Ligeti, translated by Elizabeth Uppenbrink, is taken from the liner notes to the Sony release of Le Grand Macbre in 1999.

György Ligeti Edition 8; Esa-Pekka Salonen, London Sinfonietta Voices & Philharmonia Orchestra.

The piece is set in the entirely rundown but nevertheless carefree and thriving principality of Breughelland in an ‘anytime’ century.

FIRST SCENE

An abandoned graveyard with lush vegetation

Piet the Pot, a kind of realistic Sancho Panza, is always slightly tipsy (his profession is ‘wine-taster’) and therefore always cheerful. He sees the beautiful loving couple, Amanda and Amando, who look as if they could have come straight out of a Botticelli painting. They are searching for a quiet place where they can secretly make love, but this seems difficult to manage in forever-busy Breughelland. While Piet watches the couple lustfully, Nekrotzar suddenly appears, arising from an opening grave. Nekrotzar, the Grand Macabre, is a sinister, shady, demagogic figure, humorless, pretentious, and with an unshakable sense of mission. Piet, who knows no fear, sneers at him, but Nekrotzar announces that he is Death in person and, with the help of a comet, will destroy the whole world that same night. He commands Piet to get his implements out of the grave—scythe, trumpet, cape—and to serve him as his slave. And any question as to whether Piet is prepared to do this is wholly irrelevant: Nekrotzar is the master and is accustomed to having people obey him unconditionally. Meanwhile, Amanda and Amando retire to the now-vacant grave and will sleep through the end of the world undisturbed. Nekrotzar uses Piet as a horse and rides off to the princely capital city on his neighing slave, blowing wildly on his trumpet. The lovers’ duet is heard emanating from the grave.

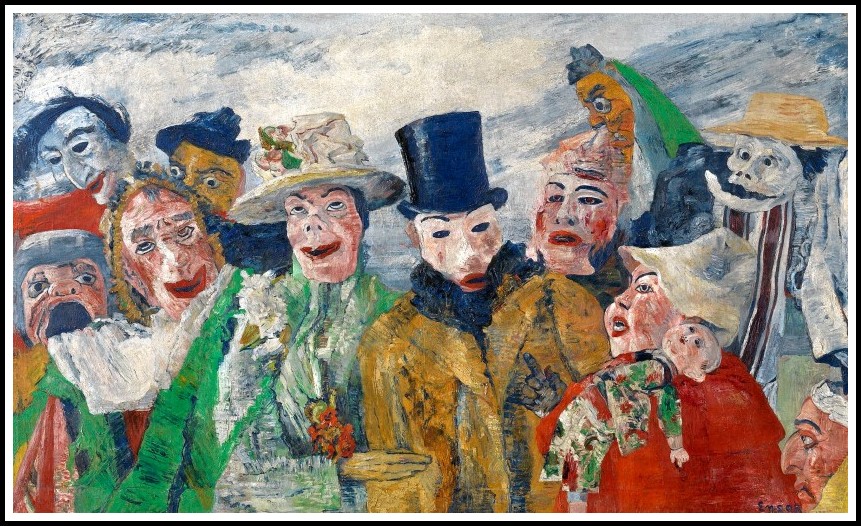

James Ensor, Intrigue, 1890

SECOND SCENE

In the house of the court astrologer, Astradamors

There is an indescribable mess in this chaotic combination of observatory, laboratory and kitchen: telescope, measuring devices, astrological charts, folios, and preparations are jumbled together with kitchen gadgets, dirty laundry and leftover food. Everything is covered with cobwebs. Mescalina is the mistress of the house and has Astradamors completely in her power. At the beginning of the scene, Mescalina is whipping him; then she attacks him with a spit and holds a horrible spider before his mouth as he lies there helpless. After this, she tells Astradamors to look at the stars. In the meantime, Mescalina has fallen asleep after slurping red wine, and dreams that the goddess Venus is finally bringing her a better man. In fact, with Venus, Nekrotzar arrives as well, riding on Piet. Astradamors recognizes his faithful boon companion Piet with joy, but Nekrotzar goes over to the sleeping Mescalina, embraces her brutally and bites her neck like a vampire. Mescalina emits a horrible scream and falls lifeless to the ground. Astradamors is thrilled. Nekrotzar orders Piet and Astradamors to remove the corpse, and they bring Mescalina’s body down to the cellar, which is identical to the grave in the first scene. At the end of the scene, Nekrotzar, sure of victory, announces the imminent end of the world. All three leave for the Prince’s palace. Astradamors returns to the house once more and, in his triumphant anger, destroys everything in it: ‘At last I am master in my own house’—and the curtain falls.

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting over the Body of a Hanged Man, 1891

THIRD SCENE

Action in front of the curtain

The gluttonous, infantile Prince Go-Go reigns in Breughelland, but is tyrannized by his two corrupt Ministers. They are the leaders of the mutually inimical White and Black political parties, which, however, have no ideological differences at all. The affairs of state are therefore conducted with a great deal of confusion: the ruling Prince has nothing to say, and the two Ministers argue constantly. They are forever threatening to resign, but repeatedly come to some brief reconciliation before quarreling all over again. They also force the Prince to carry out posture and riding exercises (for which they use a rocking horse) in order that he ‘wear a crown with dignity.’ They declare the constitution of the land to be blank paper, but force Go-Go to keep signing new decrees that raise taxes limitlessly. Prince Go-Go is hungry; he thinks of nothing but food. The curtain finally rises after a sign from one of his Ministers.

James Ensor, Masquerade, 1889

A huge pile of food and drink appears behind the curtain. We find ourselves in the throne room: the remains of earlier pomp and splendor are now strewn across the stage. For the first time, Go-Go waves the Ministers away, accepts their resignations and starts to cram food into his mouth. The chief of the secret political police (Gepopo) rushes in with his followers: odd and ghostlike detectives, torturers, and executioners. The chief of police gives Go-Go an encoded message and warns him of the arrival of an enraged, protesting mob. We hear the terrified and angry screams of the people; the pallid, reddish light of the comet shines through the window into the room. From the balcony of the throne room the Ministers try to calm the mob with pacifying speeches, but the people call for the Prince. He finally speaks to the people and beats up the Ministers, who incessantly tender their resignations. Suddenly the chief of police returns with his ghostly following, now disguised as a huge, hairy spider, then turning into a polyp. The latest encoded message warns of the arrival of a mysterious and threatening figure. The chief of police flees in a panic, but instead of the menacing creature, only Astradamors appears, cheerfully yodeling, still happy to be rid of his wife. In the meantime, the Ministers have run away as well. Go-Go and Astradamors sing and dance together. Suddenly an alarm siren starts to howl, and then another. Go-Go regresses into childish behavior, begging for help, and Astradamors hides him under the dinner table.

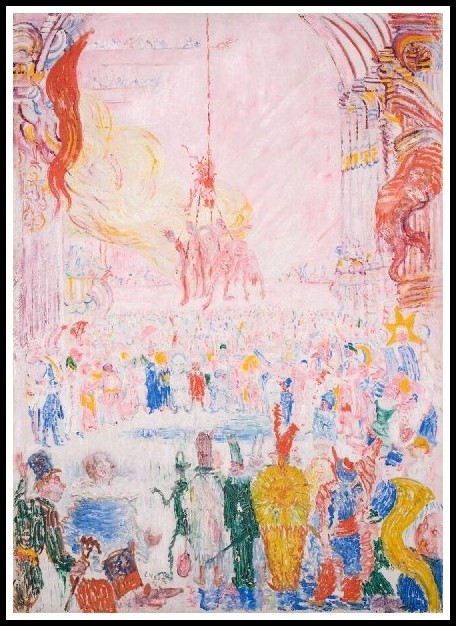

James Ensor, The Great Judge, 1898

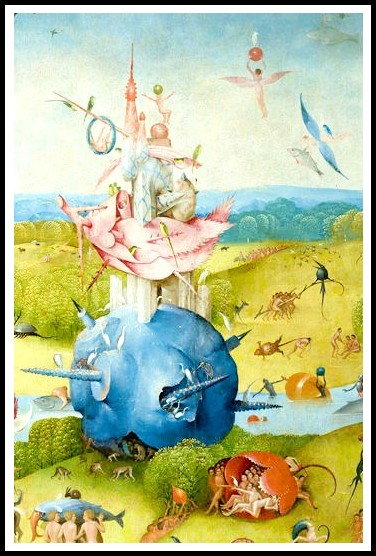

Nekrotzar now appears in dark yet magnificent grandeur, riding on Piet, blowing his trumpet and swinging his scythe. Hellish figures, masked musicians and grotesque monsters, as if out of an apocalyptic painting by Breughel or Bosch, make up his entourage. Sure of his victory and loud-mouthed, Nekrotzar proclaims the imminent end of the world. He pronounces jumbled, distorted verses from the Revelation to John. High up, behind the audience, the sound of heavenly trumpets is heard, a fanfare that will be repeated, unchanged, in very simple form. The people beg Nekrotzar: ‘Punish all the rest, but not me, me, me, do not kill me!’

James Ensor, Apparition: Vision Preceding Futurism (Nightmare), 1886

At this point, however, Nekrotzar falls under the influence of an all-too-earthly pastime of Breughelland’s citizenry: Piet offers him a glass of red wine, which Nekrotzar, in a fit of megalomania, believes to be the blood of his sacrifices, and which he needs to drink to give him strength to be abie to perform his ‘holy task.’ Piet and Astradamors keep filling his glass; the drinking scene becomes ever more ‘mechanical.’ They even give Go-Go one glass of wine after another while he is still under the table, and finally all four are drunk and staggering. Nekrotzar tallies up his list of outrages. In all this chaos, they remember the terrifying witch, with whip, stick, spit, and a horrible spider. But all are now reconciled in their drunkenness: Piet introduces the two rulers—Tsar Nekro, Tsar Go-Go—to each other. Suddenly there is an explosion and cries of fear are heard. The comet’s gleam is threateningly close. Nekrotzar cries, ‘Where am I? What time is it?’ Piet tells him in the indifferent tones of a television announcer that it is ‘umpteen seconds to midnight.’ Nekrotzar replies in panic, ‘Help! Help me! Scythe! Trumpet! Horse!’ The only horse available is Go-Go’s wooden rocking horse. With great effort Nekrotzar mounts this diminutive horse, announces that he will now smash the world, only to fall out of the saddle, drunk.

James Ensor, Hop-Frog’s Revenge, 1896

FOURTH SCENE

The same dilapidated graveyard as in the first scene

Dawn, dense fog. Piet and Astradamors imagine they are dead and in heaven. Go-Go appears, staggering. He feels he is alive, but fears he is the only living person left on the face of the earth, and that all the others are corpses. Suddenly three uncouth ruffians, Ruffiack, Schobiack and Schabernack, show up with a cart full of plundered booty. They arrest Go-Go for being a ‘civilian’ and make to kill him. Go-Go cries in vain, ‘We are Prince Go-Go!’. Suddenly, Nekrotzar appears, tall and gaunt: he had been lying under the plundered items. As Nekrotzar recognizes the Prince, the three ruffians release Go-Go and stand to attention. Nekrotzar asks, ‘Have I not just laid to waste the entire goddamned world?’

James Ensor, Pierrot and Skeletons, 1907

Enervated by disappointment and alcohol, Nekrotzar wants to die: ‘Where, where is my grave?’ Suddenly Mescalina, who had only seemed to be dead, rises from the tomb and hurls herself at him in a fury, spit in hand. Two of the ruffians grab her and keep her from stabbing Nekrotzar; the third ruffian, meanwhile, leads in the two Ministers, who are tied up with rope. The Ministers beg for mercy in a cowardly and lickspittle way, claiming they only wanted what was best for the people. They and Mescalina accuse each other of creating the astronomically high taxes, of introducing the Inquisition, and of planning to do away with the Prince. The argument leads to a general brawl, until finally everyone is lying on the ground. Piet and Astradamors stroll in, still believing themselves to be in heaven. But the Prince calls out, ‘Ah, welcome, comrades!’ and gives them wine to drink. ‘We have a thirst, so we are living.’ That is too much for Nekrotzar. ‘So, you are living’, he cries, deeply disappointed. Out of misery, he begins to shrink, gradually turning into a sort of sphere, gets smaller and smaller, and finally disappears into the ground without leaving a trace. In the meantime, the fog lifts and the sun, too, slowly comes up. Meanwhile, the lovers come out of the tomb in a state of some dishevelment and dazzled by the sunlight.

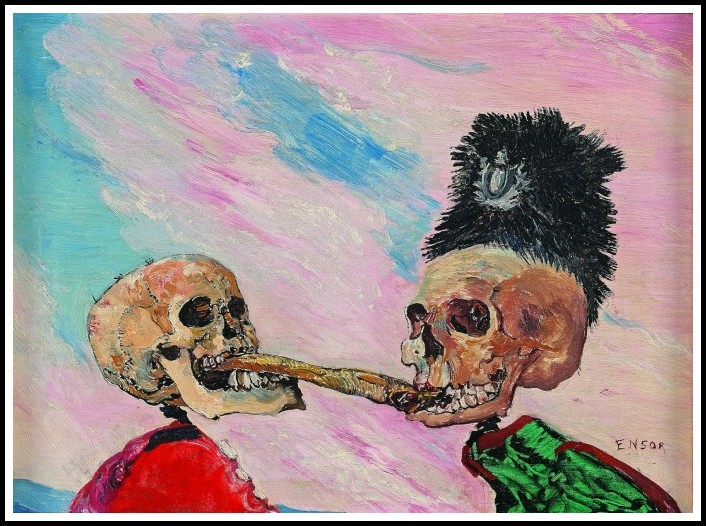

James Ensor, Skeletons Fighting Over a Smoked Herring, 1891

FINALE (PASSACAGLIA)

Amanda and Amando know nothing of the end of the world, whether it took place or not. ‘For us too the world ceased to be, and yet how ecstatic were we! Let others fear the Judgement Day: we have no fears, let come what may!’ Everyone sings the closing verses, except for Nekrotzar, who has disappeared. ‘Fear not to die, good people all! No one knows when his hour will fall! And when it comes, then let it be. Farewell, till then in cheerfulness!’ The whole passacaglia is danced with fitting elegance by all the participants. The sunlight grows paler and paler and turns into a supernatural light. Then gradually snow starts falling, covering the people on-stage.

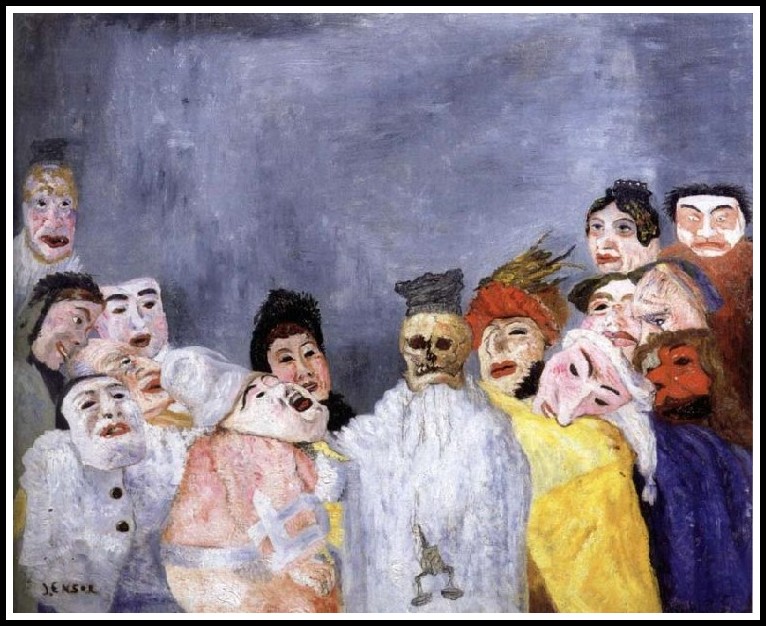

James Ensor, Masks Confronting Death, 1888

Ligeti

LE GRAND MACABRE

An Interpretation (Analysis & Commentary) by Paul Griffiths

Condensed from Paul Griffiths, Gyorgy Ligeti (London: Robson Books, 1983) pp. 98-107

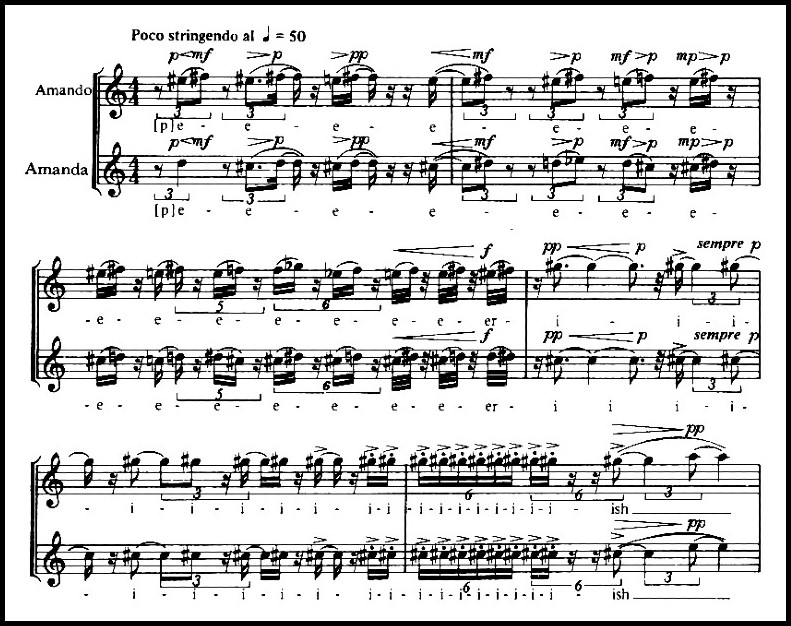

The plot of Le Grand Macabre is simple but all-encompassing, touching as it does on human games as various as sex, politics and drunkenness. The over-riding theme, though, is death. The scene is laid in the imaginary kingdom of Breughelland, the country of peasantry, monsters and apocalypses depicted in the works of Breughel. This idea comes from Ghelderode, though it is certainly one that would have appealed to Ligeti, who has described Breughel as one of his favourite painters, along with Bosch. An overture in the form of a short palindrome for twelve motor horns introduces the action, and sets a tone of run-down misuse (there will be similar preludes to the second and third scenes). We then make the acquaintance of Piet the Pot, a high tenor, the opera’s common man and the single person on stage with whom the audience might be tempted to identify. He is drunk throughout the action. Before long he has been joined by a pair of young lovers, ‘very beautiful in a Botticellian way’ (they are both played by women), called Amando and Amanda. Ligeti had no difficulty in finding sharply distinctive musical personalities; Amando and Amanda, for instance, are almost always vocally as well as physically entwined in each other, and Ligeti uses Monteverdian embellishments in a way that naughtily accentuates their relation to the breathing and emotional patterns of high sexual excitement:

György Ligeti, Le Grand Macabre, Amando & Amanda

Some similar allusive connection with other music may be found at numerous points throughout the score: Ligeti himself has mentioned Poppea, Falstaff and The Barber of Seville as among the traditions with which he makes play (not excluding also the tradition of the avant-garde), avoiding only the symphonic continuity of Wagner and Strauss. What the cited extract may also suggest is the radiant beauty of the music for Amando and Amanda, its glamorous sensuality. Breughelland, it appears, is a country in which people have their most essential characteristics wildly exaggerated, and in the case of Amando and Amanda the essential characteristic is nearness to coition. They have no separate identities, no identity at all apart from that of a couple about to couple. However, their first duet, ending as in the given quotation, is interrupted by another voice coming from a tomb seen somewhere on the stage. One calling himself Nekrotzar emerges, and in his imperious baritone takes command of Piet, declaring that he has come to announce the end of the world: he is the ‘Grand Macabre’ of the title. He sends Piet off to the tomb to fetch his instruments—coat, hat, scythe and trumpet—and then takes poor Piet as his mount to ride off bringing his message of death and destruction. Amando and Amanda meanwhile have taken themselves off to the tomb to complete their love-making in peace.

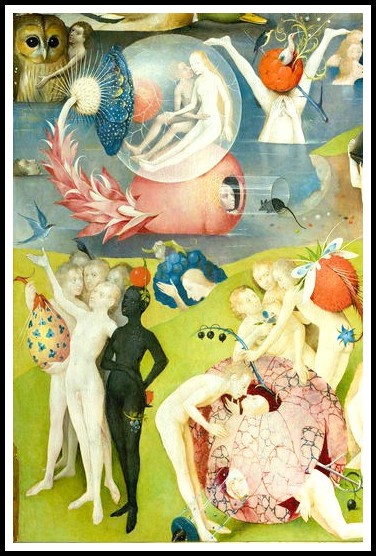

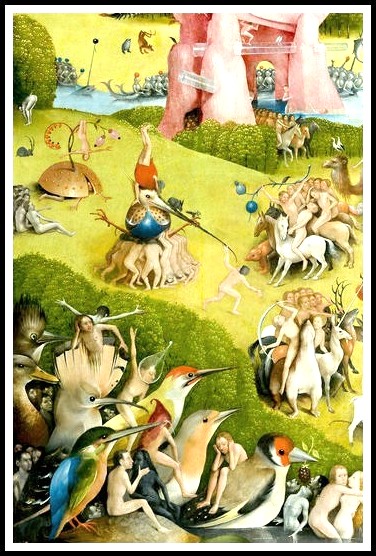

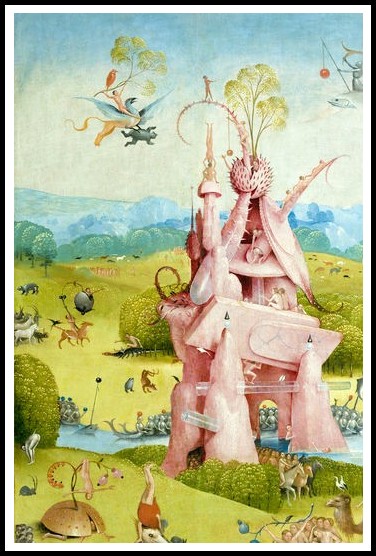

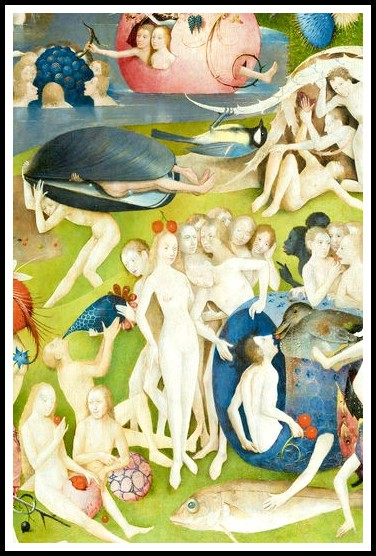

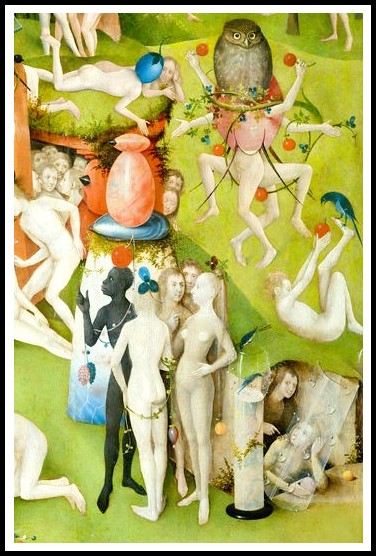

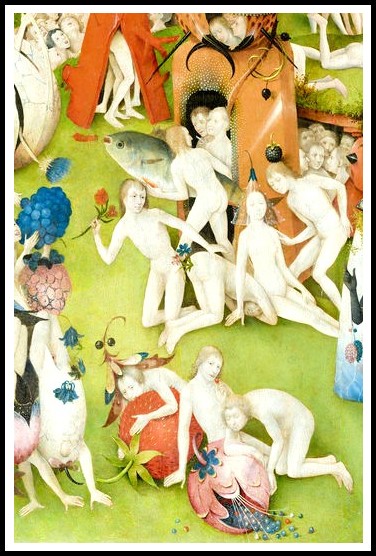

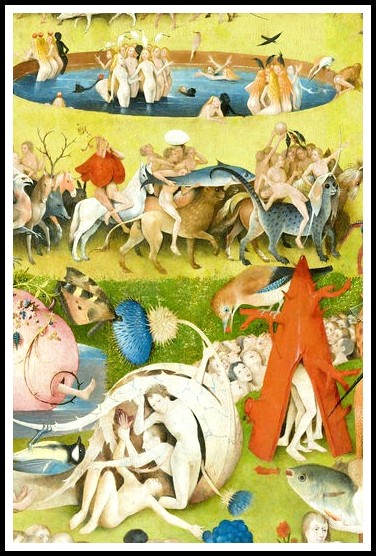

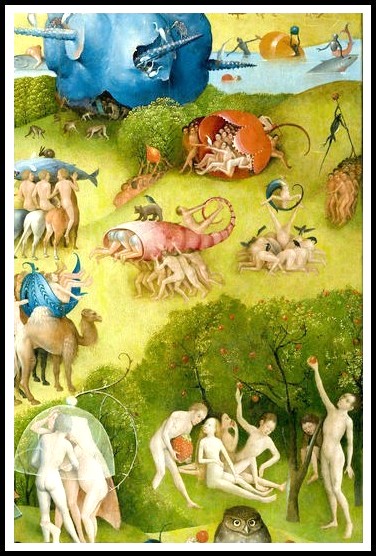

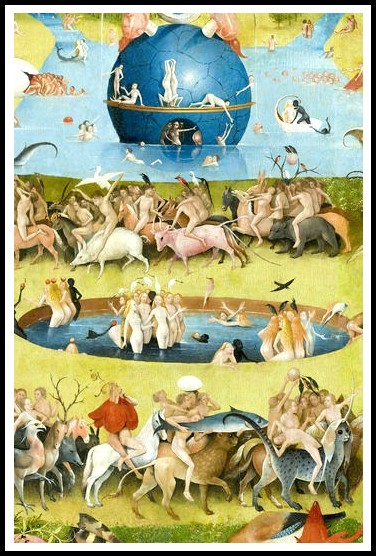

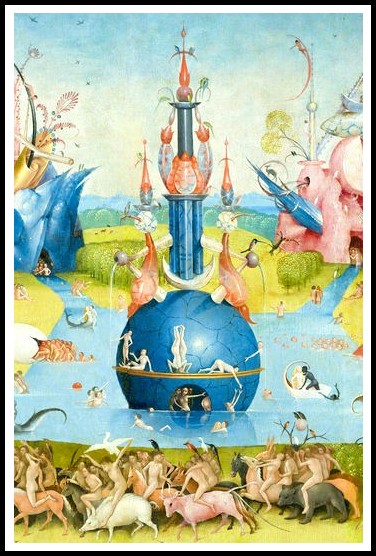

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

The second scene is concerned largely with a sexual couple whose needs are more waning and exotic than those of Amando and Amanda: they are Astradamors, the astrologer (bass), and his wife Mescalina (mezzo-soprano), he wearing women’s underwear over his trousers, she clad entirely in leather and brandishing a whip. Once their activities have culminated in a ‘bum kiss’, Mescalina dispatches her husband to his telescope. He observes, and mutters mumbo jumbo, while she has an erotic vision of the goddess Venus. Nekrotzar then enters on Piet’s back and congratulates Astradamors for having correctly prophesied his coming. He thereupon turns his attention to Mescalina, who is coming out of her Venusian dream sequence having loudly demanded a man who is ‘well hung’. He states himself to fit the bill, and in a violent embrace he kills her, first victim of the ‘dies irae’. The act climaxes in a demonically exultant trio for Nekrotzar, Piet and Astradamors, who all set off together for the palace.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

The third scene is set in the palace, that of the ruler of Breughelland, the boy prince Go-Go (the part is sung by a boy treble, or by a soprano, or by a high counter-tenor), who is besieged by two warring politicians, the White Minister and the Black Minister, both spoken roles. Driven beyond endurance by the self-satisfied bickering of these two, the prince astonishes them by accepting their resignations, but before the argument can go forward from this point, the stage is invaded by the Chief of the Secret Police and his agents. The Police Chief is sung by a coloratura soprano, who delivers a message of warning in nonsense code made the more undecipherable by musical acrobatics. Some while later the threat is revealed to be that of Nekrotzar, who makes his entry during a big orchestral set piece, taking the form of a ‘Collage’ where one stratum, repeating in the bass, is a disjointed version of the theme from the finale of Beethoven’s Eroica symphony, where the highly distinctive rhythm is retained as a skeleton while the pitches are quite altered. Above this there is a gathering madcap collage of cheap dance music: a ragtime two-step played by a solo violin, a cha-cha from wind and drums. Also sounding through the medley are banal fanfares, which eventually take over and remain to punctuate Nekrotzar’s announcement in fuller terms of the coming doomsday.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

But while there is still some time left, Astradamors and Piet are all for spending it drinking the wine laid out on the palatial table, and Nekrotzar joins them in an alcoholic trio, he seemingly believing himself already to be drinking human blood. At the end of this he departs into a curious distracted reverie, accompanied by music of a fantastic rococo sort, and recalling his satanic destructions of the past: this section is entitled in the score ‘Galimathias’, or gibberish. He is, however, recalled to his task at the approach of midnight, and calls down nothingness as the orchestra slowly marches through a sequence of wide-spread chords, beautiful and ominous. Then, as a canon in the orchestra slowly slips downward, Nekrotzar himself falls: the end of the world has come, and the only one to die is Death himself, to a musical gesture similar to that which had ended the two-piano triptych. The curtain slowly descends as another dense, still orchestral texture gradually turns into a confused gallop in the low brass.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

The fourth scene, or Epilogue, has no separate overture but develops straight out of its predecessor. The setting is the same as for the first scene, ‘In the lovely country of Breughelland’, where first of all we meet Piet and Astradamors, who believe themselves to be dead. Before long all the rest have turned up as well: Mescalina, Go-Go, the Ministers, Nekrotzar and finally, emerging from the tomb where they have been settled for two whole scenes, Amando and Amanda. Have they really all perished and been resurrected to find themselves in much the same situation? Does the great mystery of death therefore hide nothing more than the boring fact that everything continues as before? Or was Nekrotzar merely a powerless charlatan? In Ghelderode’s play he is shown up as a fake, but in the opera the question remains open, as Ligeti wanted, and the only possible moral is pronounced in the concluding passacaglia, where all the principals join together: Fear not to die, good people all! / No-one knows when his hour will fall. / And when it comes, then let it be / Farewell, till then, live merrily!

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

If Le Grand Macabre has been so successful, it is partly because the work treats a subject of concern to all. To die, we know, is common. No life is complete without death. Moreover, in the world since 1945, no life has been lived without the constant threat of a possibly imminent extinction and the constant knowledge of what horrendous wickedness the human race is capable of committing. Le Grand Macabre may appear to consider these matters with undue levity, but in the face of catastrophe, of colossal manoeuvres which seem to be wholly beyond the individual’s control, irony is just about the only weapon one has left. It must also be said that we live in a time when the bluff of the great artist has been called. If Ligeti were to claim in Le Grand Macabre some special insight into life and death, the opera would be simply idiotic; it can be valuably, and amusingly idiotic only because it recognises the absurdity of the questions it raises, questions about the nature of death above all. And of course the final moral is as seriously silly as the rest. One does not need to spend two hours in the opera house to be told that death will come and meanwhile we may as well enjoy ourselves, but in Le Grand Macabre that is the only possible message, and it belongs most decidedly within a work which makes large statements obliquely and very small ones directly.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

This matter of voice is crucial. Le Grand Macabre is of course a work about the human condition. Its agents, however, have more the quality of puppets. All the characters are unashamed caricatures: the convivial sot, the impotent monarch, the jargon-spouting politicians, the leather-clad dominatrix. They are as crisply defined and neatly framed as cartoon personalities. And because they are puppets they can embody an honest response to events and situations that have cauterized us all, and not least those who, like Ligeti, have lived through both Nazi and Stalinist terrors. No more ‘human’ treatment could be adequate, only bathetic or worse, and certainly the marionette character of the drama is intended not simply to render the action fantastic and humorous, but to underline its seriousness by the only means possible. That seriousness gains a new dark gravity once one understands that Ligeti would see Nekrotzar as a low but hugely insidious clown on the model of Hitler: one intoxicated with annihilation on the grandest scale.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

The puppet nature of the opera is of course as much musical as scenic, and in that respect Le Grand Macabre is of a piece with everything Ligeti has written: the music is presented not as an immediate expression, but as something artificial and odd. It is, for example, not surprising to find Ligeti coming near the style of Almosphères, declaredly a memorial piece, when the end of the world arrives (if it does). Nor is it altogether strange that there should be various resemblances with the Requiem, even to the extent of a similar quaternary plan. First comes preparation, in the opening scene of the opera and the ‘Introitus’ of the Requiem, followed by a more colourful extension in the Astradamors-Mescalina scene and the ‘Kyrie’. In both works the third part is apocalyptic, and in both the fourth takes up the story after the end of the world. The mood is subdued—becalmed but also disjointed, as if in reaction to the preceding upheavals the music has been jolted to a standstill but at the same time shifted into a whole new area of discourse. In the case of the ‘Lacrimosa’ from the Requiem, the new discovery was that of tangible harmonies, and it was one that was immediately to affect the course of Ligeti’s music. The final scene of the opera, in its turn, may prove to have been no less epoch-making.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

This time the discovery is that of harmonic progression, the natural next step in Ligeti’s progressive re-absorption of the elements of western music, and though the final scene makes use of the acquisition most abundantly, it has been more or less apparent at times in the earlier scenes as well. Most notably, the ‘Galimathias’ depends very much for its sense of musical as well as verbal nonsense on the continual frustration of expected resolution. The phraseology of the music is blithely classical, but its harmonic progressions are always eluding a cadence, spiralling on instead of stopping to start again. In the concluding passacaglia the harmonic objects are mostly thirds, sixths and triads, but they are arranged so as not to fit into any coherent tonal pattern, and therefore to suggest a world in which the features are recognizable but the rules are entirely altered. Moreover—and this only makes the alterations more disquieting—there is no sense of a desperate avant-garde flouting of tradition but rather of a blank forgetting of how things used to be.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

Opera is, by its nature, concerned with how things used to be, since, as is well known, the operatic repertory consists almost exclusively of works written before the death of Puccini in 1924. For a contemporary composer to write an opera about death might, therefore, appear rather pointed, though in fact the matter is not so cheap or so simple. What is important is that opera is, for any composer today, an ‘outside’ medium: one in which the composer is unlikely to have much practical creative experience, and one that might well seem unnatural and ill-suited to his temperament and aims. Ligeti’s own earlier comments on the genre convey feelings of this kind, and it is surely not just a joke when he describes his progress to Le Grand Macabre as won by diametric opposition to the medium.

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

In Le Grand Macabre the mismatch is one of time, for it is an opera written after the great age of opera, lasting from Monteverdi to Puccini and Berg, had passed away. It is conscious of the fact: a reference to Monteverdi has already been noted, and the rest of the score is filled with allusions to other operas, especially to operas whose composers have, like Ligeti, sought to express human characteristics directly in vocal behaviour rather than by means of musical symbolism. Even though nothing is as bodily present as the Eroica finale, the world of opera is the world in which Le Grand Macabre works, if it works at all. The condition is totally necessary. While raising doubts about the death of the individual human being and about the death of human civilization, Le Grand Macabre also raises doubts about itself, and not the least of the open questions at the end is that of the work’s own standing. Is it a living, breathing masterpiece to be added to the repertory? Or is it a fake? Or could it possibly be both?

Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1500 (detail)

Synoptic Chart: Figures, Characters, Musical Structure

LE GRAND MACABRE

Michael Searby

From Michael Searby, Ligeti’s Stylistic Crisis: Transformation in His Musical Style 1974-1985 (Toronto: Scarecrow Press, 2010) pp. 179-182

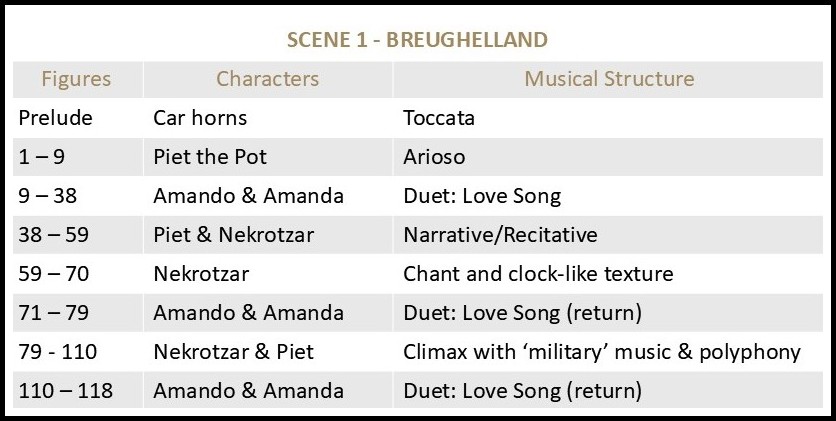

Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre – Synoptic Chart – Scene 1

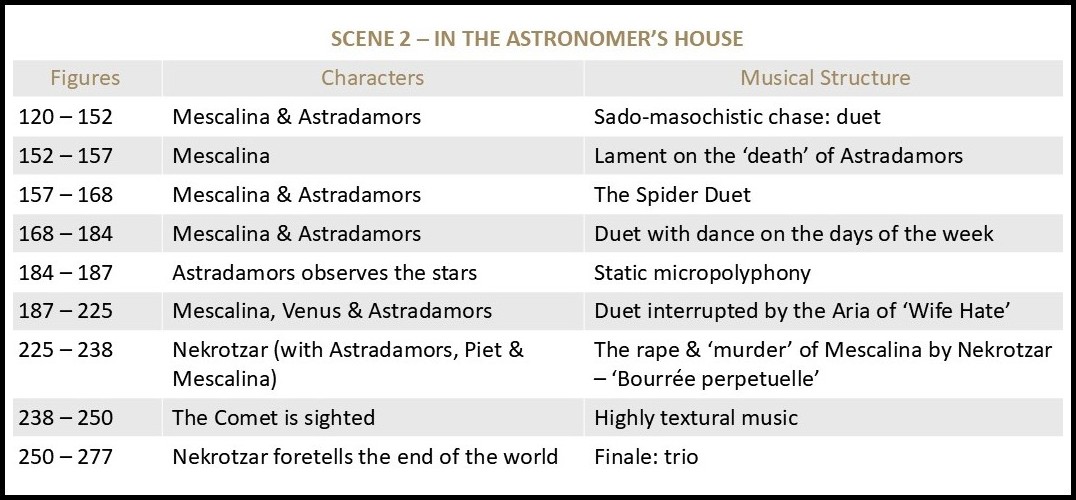

Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre – Synoptic Chart – Scene 2

Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre – Synoptic Chart – Scene 3

Ligeti – Le Grand Macabre – Synoptic Chart – Scene 4

Ligeti

LE GRAND MACABRE

Concert Performance by François-Xavier Roth, Orchestre National de France, Choeur de Radio France

Ligeti

MYSTERIES OF THE MACABRE

Barbara Hannigan | Simon Rattle, London Symphony Orchestra

RELATED POSTS IN THE WORLD OF MARA MARIETTA