Nina Hagen

Naturtränen

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

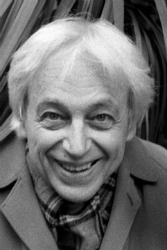

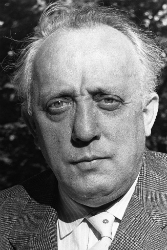

What a delicious surprise! Transposed to string quartet, ‘Naturtränen’ is magical. Listen! Holding irony and innocence in tension, the soprano embodies the spirit of the song. Look! She takes me back to London, 1979. I was working on a screenplay on a gloomy Sunday when Jane came by with two tickets to see a German band. ‘I heard Nina Hagen sings Schubert to Johnny Rotten’, she said, ‘let’s go and see her, she’s playing at the Lyceum’. A few hours later we were floored by the virtuosity that came from Nina’s malleable mouth; the songs were excellent and the band kick-ass. ‘She’s an original’, Jane said, ‘she’s the real thing’. Yes, ‘punk from East Berlin’ was a pigeon-hole that couldn’t confine her: Possessed of the sacred fire, she could fly. Now here she is being sung by a red-haired soprano in Reykjavik, a metempsychosis that testifies to the shamanic power of art. Is it not here where I belong, rather than in the throes of love? Marietta, go, if you must, but know that when you’re gone, I’ll love you through my powers as a shaman!

Nina Hagen Band, Lyceum, London 1979

Nina Hagen

Listen! The singer now begins the ravishing vocalise. The beauty of her voice against the strings is overwhelming: If you’ve got to go, Marietta, go now, before the music’s over: Enfolded in this voice, I can bear your leaving.

Listen! The exclamation that interrupts the coloratura blows me away just like it did in London; the guttural snarl that reclaims rock from opera moves me now just as it did then: If music renews itself in each performance, have I renewed myself? The viola drones under the violin harmony; the cello plays a heavy bass line. Well, have I renewed myself?

Nina Hagen | ‘Love never fails’

Listen! The singer is in the flow of her vocalise; she is at once aware and unselfconscious, focused and at ease.

NINA HAGEN, NATURTRÄNEN | GERMAN AND ENGLISH LYRICS

Nina Hagen (words and music) | English translation by Richard Jonathan

Off’nes Fenster präsentiert

Spatzenwolken himmelflattern

Wind bläst, meine Nase friert

Und paar Auspuffrohre knattern

Ach, da geht die Sonne unter

Rot, mit Gold, so muss das sein

Seh ich auf die Strasse runter

Fällt mir mein Bekannter ein

Prompt wird mir’s jetzt schwer ums Herz

Ich brauch’ nur Vögel flattern sehen

Und fliegt mein Blick dann himmelwärts

Tut auch die Seele weh, wie schön

Natur am Abend, stille Stadt

Verknacksen Seele, Tränen rennen

Das alles macht einen mächtig matt

Und ich tu’ einfach weiterflennen

Vilhelm Hammershoi, Interior with Woman Standing, n.d.

Vilhelm Hammershoi, Interior with Flowerpot, n.d.

Opened wide my window reveals

A cloudy sky, sparrows aflutter;

The wind blows, my nose freezes

And sputtering exhaust pipes roar and rattle.

Ah, here comes the setting sun,

Red with gold, inevitable;

In the narrow street down below

I see someone I used to know.

Now of a sudden my heavy heart sinks.

The sight of twilight birds on the wing

Sends my sad gaze soaring skywards:

Sore is my soul, and how lovely it is.

Evening still-life, nature-city;

Soul in torment, tears a-running:

So all conspires to make me weary

And I just keep cannot keep from crying.

AUDIO & VIDEO: NATURTRÄNE, NINA HAGEN BAND

Nina Hagen Band, ‘Naturtränen’ | Original audio recording, 1978

Nina Hagen Band, ‘Naturtränen’ | Top Pop, Netherlands

NINA HAGEN: INTERVIEW EXTRACT

From PaperMag, 4 October 2002

‘I never said I am doing punk music. I never said I am a punk. They said that. I wanted to do rock music since I was 12 years old. It touched my heart to hear Tina Turner, the Beatles. And they were all my singing teachers because I made cassettes. And I sang along. And I wanted to make music like that.’

Born and raised in Berlin, East Germany, CBS Records signed Hagen in 1976 when she was 21. They knew she could sing ‘like a walking volcano,’ as she says, but they wanted her to learn live performance. So they gave her a lot of time and some money to go to London.

‘I saw all the punk bands and when I came back to Berlin I cut my hair short and made black lipstick’, Hagen says. ‘And then they said I’m a punk. I am an entertainer. I sing political cabaret and spiritual cabaret and I write songs about anything concerning life. So it’s just maybe one aspect of my art, punk art.’

Nina Hagen

Click on the image to see English lyrics for ‘Auf’m Bahnhof Zoo’ and ‘TV-Glotzer’ from the album Nina Hagen Band (1978).