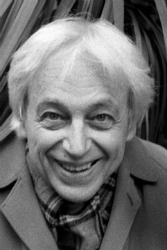

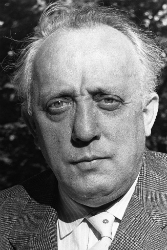

Hans Werner Henze

GUY RICKARDS ON HANS WERNER HENZE AND HIS WORK DURING THE YEARS 1953-1966

From Guy Rickards, Hindemith, Hartmann and Henze (London: Phaidon Press, 1995) pp. 140-149

When Henze crossed the Italian frontier in 1953 he kept on driving until he reached Venice. There he felt he could safely drink in the Italian atmosphere. He quickly moved on, crossing Tuscany (with a brief stopover near Florence) in a few days. His target was Ischia, the small island in the Bay of Naples which he had visited two years previously. Ischia was still largely undiscovered; a poor fishing community surrounding a small seasonal population of artists—some of whom were of considerable eminence. The self-exiled British composer William Walton had settled there with his Argentine wife, Susana. Also present on the island were the choreographer and director of the Royal Ballet at Covent Garden, Sir Frederick Ashton, and the world-famous poet, Wystan Hugh Auden. The Waltons were permanent residents but Auden, with his companion Chester Kallman, would spend the summer months on Ischia each year, then would go ‘back to New York to make money’. Henze rented a tiny cottage—it had no running hot water so he had to visit the local village for a bath—and settled down in this peaceful idyll. He had with him the still incomplete score of Ode to the West Wind, his extended instrumental evocation for cello and orchestra of Percy Bysshe Shelley’s well-known poem, plus the plan and some sketches for the Gozzi opera, König Hirsch (‘King Stag’).

Hans Werner Henze, Ischia, 1954

Hans Werner Henze, 1964

Despite his absence from Germany, Henze’s music was in high demand. Ein Landarzt was given a staged production in Cologne in May and Northwest German Radio, which first broadcast the work, wanted another. Das Ende einer Welt (‘The End of a World’) received its première on 4 December. The première of Ode to the West Wind took place in Bielefeld on 30 April 1954, and his ballet after Tchaikovsky Die schlafende Prinzessin (‘The Sleeping Princess’) in Essen on 5 June. During this year Henze reduced Ein Landarzt to a concert monologue for baritone singer and small orchestra; the radio version was awarded the prestigious Prix d’Italia.

Few of his works caused Henze such effort, or suffered such a chequered history, as König Hirsch. Completed late in 1955, it had its first performance during the Berlin Festival on 23 September 1956, in a drastically cut version by Hermann Scherchen. There were noisy demonstrations of approval and opprobrium from the audience for nearly half an hour afterwards. Composer and conductor were held jointly culpable but Henze remained bitter about Scherchen’s involvement. That the score was special to him is confirmed by a letter written in January 1973 to Joachim Klaiber: ‘It should be seen as a diary, an autobiography, which tells how I discovered music.’ Scherchen’s pre-eminent place among the avant garde had made him aggressive and overbearing; he was known to musicians as the ‘Red Dictator’.

In 1955 Henze constructed his Fourth Symphony from the opera’s second-act Finale and in 1990, he extracted a further short orchestral work, La selva incantata (‘The Enchanted Wood’), from the music of the final act. The original version of the opera, which Henze had always preferred, was not performed until May 1985, when the American Dennis Russell Davies conducted it in Stuttgart.

Hans Werner Henze, 1963

Socially, Henze’s three years on Ischia were immensely beneficial. He was invited to a party at Auden’s house where he met Walton, who took the young German under his wing. Henze invited Walton and his wife to the première in Naples of Boulevard Solitude. ‘My dear boy,’ he told Henze afterwards, ‘in ten years’ time you will be a world success’. Stravinsky was also present and, although he later attempted to deny it (for reasons that remain unclear), wrote to Willy Strecker that he found ‘incomprehensible the behaviour of part of the audience’ and that the performance itself was ‘very impressive and full of talent’. In a televised interview Walton singled out Henze as the most talented of the younger generation. The two composers travelled together across Italy to attend performances of operas of mutual interest, such as Prokofiev’s The Fiery Angel.

In December 1954, Walton invited Henze to the première at Covent Garden of his opera, Troilus and Cressida. The British immigration authorities refused to allow Henze into the country until Walton had personally vouched for him. On Ischia the Waltons liked to host dinner parties and at one Henze received an extremely unpleasant surprise, as he recalled to the present writer: ‘They had a German who had been recommended to them who had just come out of Spandau jail, Baldur von Schirach, the Nazi leader, as a guest. I left immediately; they didn’t know who it was but for me it was the most shocking thing.’ As a boy, Henze and his brother Gerhard had had a poster of Hitler on their wall with a motto written by Schirach: ‘Each German boy and girl should thank God on their knees every morning that they have got the Führer.’ The music-loving Schirach was head of the Hitler Youth, which Henze had been forced to join.

Hans Werner Henze, 1966

While putting the finishing touches to the opera, Henze produced two further orchestral scores which were given their premières by two of the most prestigious international conductors of the day: Quattro poemi (‘Four Poems’) by the American Leopold Stokowski in Frankfurt in May 1955, and Three Symphonic Studies by the French conductor and composer Jean Martinon in Hamburg the following February. In January 1956, Henze left Ischia, crossing the Bay to live in Naples itself. The impact of urban Italian life made itself apparent in his music almost immediately, in the more obviously Italianate vocal writing of works such as Five Neapolitan Songs composed straight away for the German baritone, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and first performed that May.

Two ballet commissions involved Henze in working with two artists of the highest calibre. Maratona di danza (‘Dance Marathon’) was the idea of Luchino Visconti, best known as a film producer. The ballet deals with a young boy in post-war Rome who is caught up in and killed by the dance marathon craze common to many countries at the time. The music caused Henze difficulty due to the requirement to use jazz for the marathon, and jazz of a sleazy and unimaginative type at that. The second ballet was more conducive to his skills and brought him into contact with Sir Frederick Ashton, who wanted a full evening ballet for Covent Garden. He had originally approached Walton who, smarting from the indifferent reception of Troilus and Cressida, suggested Henze as a replacement. The ballet Ondine was staged in London on 27 October 1958, to Ashton’s choreography with Margot Fonteyn in the title role as the water nymph of Friedrich de la Motte-Fouqué’s story.

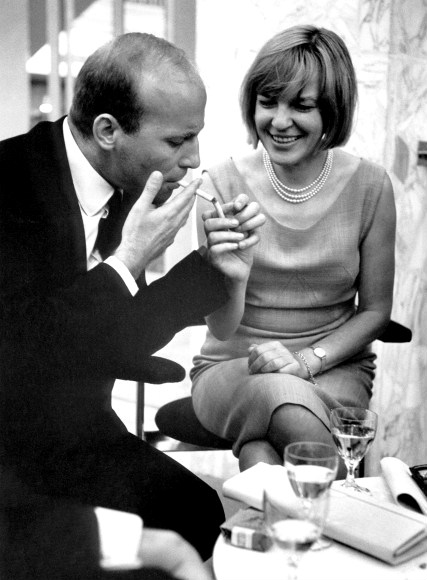

Margot Fonteyn, Frederick Ashton, Hans Werner Henze | Ondine première, 1958

Both Maratona di danza and Ondine provided ammunition for Henze’s opponents within the avant garde who felt he had ‘betrayed the cause of modern music’. His employment of jazz in the one and Stravinskian, neo-classical elements in the other, led to accusations of stylistic impropriety in that he wavered between different types of music without committing himself to one camp. Henze had in any event become acutely disenchanted with developments at the Darmstadt summer school, to which he had returned in 1955 as a lecturer. Pierre Boulez and Karlheinz Stockhausen had become the driving forces in what was by then the powerhouse of experimental music. Henze had little sympathy with their aesthetic and in turn they demonstrated their disapproval of his music in 1958 by pointedly walking out of the first performance of Nachtstiicke and Arien (‘Nocturnes and Arias’) at Donaueschingen.

Nachtstiicke und Arien was a set of orchestral pieces encompassing settings of two poems by the Austrian poet, Ingeborg Bachmann, who helped adapt the libretto for Henze’s next opera, Der Prinz von Homburg (‘The Prince of Homburg’), from the play by Heinrich von Kleist. The initial suggestion had come from Visconti, but Kleist’s story of the individual caught by and defying the machinery of the State, possessed a real and pertinent appeal to the composer, both in the wider context of German political life as well as in his relationship to the musical establishment. Henze’s music fell between two stools: too adventurous for the conservative press and the bulk of opera-loving audiences (which did not stop them turning out to hear it), it was also not radical enough for the pioneers. Der Prinz von Homburg was, however, staged right across Germany in most of the leading, and many lesser, opera houses, becoming more viable commercially than any of its predecessors. Henze had taken great pains with this score, for the first time working out many of the compositional problems in smaller-scale, satellite works. These included Kammermusik 1958, the orchestral Three Dithyrambs, sonatas for string orchestra and for piano, and the pantomime Des Kaisers Nachtigall (‘The Emperor’s Nightingale’).

Hans Werner Henzer & Ingeborg Bachmann

Kammermusik 1958 is totally unlike Hindemith’s works of the 1920s, being not a concerto but an extended song-cycle for tenor, guitar and eight other performers, setting Friedrich Hölderlin’s ‘In Lovely Blueness’. The cycle was composed during a visit to Greece, the inspiration also for Hölderlin’s fragmentary poems, to a commission from North German Radio. It was dedicated to another English composer, Benjamin Britten, as ‘a true act of homage and an expression of gratitude for the inspiration that his works have given me’. Henze had encountered Britten’s music in 1946 with Peter Grimes and was particularly impressed with the four ‘Sea Interludes’, often performed separately as a concert suite. The two composers later struck up a cordial relationship, Britten returning the compliment by dedicating his setting of Brecht’s Children’s Crusade to Henze in 1968. Five years after completing Kammermusik 1958, Henze added a purely instrumental epilogue celebrating the seventieth birthday of Josef Rufer, a disciple of Schoenberg. (Rufer’s writings on twelve-note composition had been widely praised and had even made a favourable impression on Hindemith.) The three guitar interludes, or Tentos, from Kammermusik 1958 were in addition published separately and have enjoyed success independently in the recital room.

In 1959, Henze linked up with his erstwhile neighbour on Ischia (and Britten’s former collaborator), W. H. Auden. Whilst on the island, Henze had been in awe of both Auden and Kallman, still fresh from their triumph with Stravinsky in The Rake’s Progress. ‘When I lived there,’ Henze confided, ‘I saw them quite a lot but I still didn’t have the courage to ask them about a possible collaboration. Years later when I had left Ischia I wrote to them in New York and the answer was affirmative.’ The result was another opera, Elegy for Young Lovers, and occupied Henze from 1959 until 1961. The opera takes its title from a poem which is about to be declaimed publicly as the opera ends. If heard, the poem would recount the tragic events of the opera as a further example of the manipulative poet Mittenhofer’s subjugation of the lives—and deaths—of those around him to the service of his art. Elegy for Young Lovers was first performed in a German translation in Schwetzingen in May 1961.

Inevitably, comparisons were drawn with The Rake’s Progress and both music and libretto were often found wanting. Writing in 1964, Wolf-Eberhard von Lewinski found the opera ‘so complex and unusual in terms of plot that it does not draw the favour of the larger public’. This did not prevent the work from being rapidly taken up in Switzerland, Germany and Britain and becoming something of a modern classic. So pleased with it were the librettists that they immediately suggested to Henze a new opera, to be based on the ancient Greek drama, The Bacchae, by Euripides [The Bassarids, 1966]. Elegy for Young Lovers also provoked an irreconcilable row between Stockhausen and Herbert Eimert, the director of the electronic studio in Cologne where Stockhausen worked. Eimert had reported back of his delight with Henze’s music; Stockhausen considered it anathema.

Henze moved from Naples to Rome in 1961, where he received a commission from the New York Philharmonic Orchestra for a new symphony—his fifth. He completed it in 1962 and it was premièred the following May by Leonard Bernstein. He completed the recomposition of the early First Symphony as a three-movement chamber work, conducting its first performance in April 1964 with the Berlin Philharmonic. Henze had begun to develop a closer relationship with this orchestra following a commission for a short orchestral piece in 1959, Antifone, given its première by Herbert von Karajan in January 1962. The same orchestra finally gave the much-delayed first performance, under Henze’s direction, of the Fourth Symphony during the Berlin Festival in October 1963.

Sellner, Kallman, Auden, Henze | The Bassarids, Salzburg 1966

Henze’s principal preoccupation was still with the human voice. Ariosi is a group of five songs for soprano, solo violin and orchestra (the composer later made a version for piano, four hands) to words by the medieval Italian poet, Torquato Tasso. In Ariosi Henze further refined the delicate melodic writing that had characterized the Neapolitan Songs, Nachtstiicke and Arien and Kammermusik 1958. He next turned to the poems of the Frenchman, Arthur Rimbaud (set by Britten in his song-cycle Les Illuminations) with the cantata Being Beauteous, perhaps the ultimate refinement of his vocal style of his first ten years in Italy. Henze also produced two choral works, the fifty-minute cantata Novae de infinito laudes (‘New Praises of the Infinite’, 1962) and the more modest Cantata della fiaba estrema (‘Song of the Final Fairytale’, 1963). Novae de infinito laudes set texts by the sixteenth-century Italian writer Giordano Bruno. Commissioned by the London Philharmonic Society, it was too expensive to rehearse even with a reduced orchestra and its eventual première, on 24 April 1963, took place at the Venice Biennale festival with Elisabeth Söderström, Kerstin Meyer, Peter Pears and Fischer-Dieskau. Among the audience were Britten and the visibly ailing Hartmann, whose Eighth Symphony was first performed during this same festival. The celebrity of performers and audience alone was a measure of Henze’s stature in his late thirties in the world of music.

HANS WERNER HENZE’S ‘NOCTURNES AND ARIAS’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Ten Chapter 13

Over harp-plucked arpeggios, woodwinds and strings, the full-blooded soprano soars; dark and dramatic, she sweeps me up into this evocation of a relationship gone wrong. I lose my bearings, lost in the myriad modulations: So this is the architecture of breakdown, this is the fog that enfolds when rhythm becomes unfixed and tone has no home. I cling to the words of the poem, the poem that Ingeborg Bachmann slipped into a letter to her ex-lover, Paul Celan. For all its dissonance, the music is ravishingly lyrical, alternating vehement strings with the understated violence of woodwinds.

Ingeborg Bachmann

IM GEWITTER DER ROSEN

Ingeborg Bachmann

Wohin wir uns wenden im Gewitter der Rosen,

Ist die Nacht von Dornen erhellt, und der Donner

Des Laubs, das so leise war in den Büschen,

Folgt uns jetzt auf dem Fuß.

Wo immer gelöscht wird, was die Rosen entzünden,

Schwemmt Regen uns in den Fluß. O fernere Nacht!

Doch ein Blatt, das uns traf, treibt auf den Wellen

Bis zur Mündung uns nach.

IN THE STORM OF ROSES

Bachmann, tr. Peter Filkins

Wherever we turn in the storm of roses,

The night is lit up by thorns, and the thunder

Of leaves, once so quiet within the bushes,

Rumbling at our heels.

Wherever the fire of roses is extinguished,

Rain washes us into the river. O distant night!

Yet a leaf, which once touched us, follows us on waves

Towards the river’s mouth.

Do you know, my love, the story that gave rise to this anguished song? It goes like this: At the crossroads of the twin plagues, in 1942, a young man from a German-speaking Jewish family tries in vain to persuade his parents to escape while there is still time. The parents stubbornly insist on staying; in a fit of anger the son leaves the house. That very night, the Masters of Death come to arrest his parents. In a forced labour camp the father dies of disease; worked to exhaustion, the mother is shot in the head. Wracked by guilt, the son is overcome, traumatized by the consequences of what he did and failed to do. He survives the war, and three years after its end moves to Paris. There, writing in German, he pursues the practice of poetry.

Paul Celan

In Austria, in 1938, a twelve-year-old girl finds her father jubilant after the incorporation of her country into the Third Reich. A full-fledged Nazi from the earliest hour, he is finally free to openly devote himself to the Masters of Death. She grows up to become a famous poet, known for her visceral opposition to Fascism. Torn between her passion for truth and her need to deny, she will never be frank about her father.

[For more on this, see (in French) Inge von Weidenbau, ‘Une amitié, entre langage et silence’ in Europe, aout-septembre 2003, pp. 18-31]

In Germany, in 1935, a nine-year-old boy is enrolled in the Hitler Youth. In 1942 he begins his musical studies. In 1944 he is conscripted and promptly captured; he waits out the war in a British prisoner-of-war camp. After the war, he resumes his studies and becomes a composer. In 1953, elated as if rescued from a disaster—from the beginning he had hated the Masters of Death—he crosses the Alps into Italy, the country in which he will make his home.

Hans Werner Henze, 18 years old, May 1944 | HWH Foundation

Hans Werner Henze, 1947 | HWH Foundation

In Vienna, in January 1948, the Austrian poet meets the poet from the crossroads; they strike up a friendship, and later a love affair. In Paris, in 1950, they live together for two months. The relationship is turbulent; the couple never manage to set it on a stable footing. In 1952 the poet from the crossroads marries a French woman. That same year, the Austrian poet meets the German composer; a year later, she visits him in Italy and they end up living and working together (he is homosexual). She writes ‘In the Storm of Roses’. A few years later, she adds a second stanza and sends it to the poet in Paris. The new stanza speaks of a leaf he had given her; she says in her letter that though the leaf is no longer in her medallion, it is not lost: She still thinks of him. The composer sets the poem to music.

In 1970, in Paris, the poet from the crossroads jumps off the Pont Mirabeau and drowns himself in the Seine. In 1973, in Rome, the Austrian poet—no longer living with the German composer—suffers serious burns when an unextinguished cigarette sets her bedroom ablaze. Hospitalized, she is deprived of the barbiturates she is addicted to and suffers seizures as a result. She dies a few weeks later. The German composer is devastated by her death; his music takes a darker turn. When they would write to each other, they would often write in Italian, and occasionally English and French: Where the poet from the crossroads cultivated an ever-greater intimacy with the German language, the two friends who felt ashamed of their parents and homeland needed to distance themselves from it. Listen! The singer ends the song, speaking of a leaf floating towards the mouth of a river.

Ingeborg Bachmann & Hans Werner Henze in 1965 |Photo: Ilse Buhs, Schott Music

Hans Werner Henze | Art Haus Musik DVD: Leaving Home: Orchestral Music in the 20th Century, Vol. 7

Did you hear, my love, in the maelstrom of this music, the nexus of relations in which the song arose?

Did you hear the anguish at the intersection of history, family, and vocation?

Ingeborg Bachmann | Photo: Herbert List

Paul Celan, Frankfurt, 1964

In sum, did you hear how happiness is overcome by horror?

VIDEO: HANS WERNER HENZE BY SIMON RATTLE, JULIAN BREAM & ARS NOVA COPENHAGEN

Hans Werner Henze & Julian Bream

Hans Werner Henze | Orpheus-Wire I

Hans Werner Henze | Orpheus-Wire II

Hans Werner Henze: 8m51s to 16m41s

SPOTIFY: HANS WERNER HENZE, ORCHESTRA & VOICE

Hans Werner Henze | Being Beauteous

Hans Werner Henze | Nachtstücke und Arien

Hans Werner Henze | Kammermusik 1958