Tamara de Lempicka

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA & DANDYISM (I)

Salvatore Schiffer Daniel

From Salvatore Schiffer Daniel, Le dandysme, dernier éclat d’héroïsme (Paris: PUF, 2010) pp. 201-210. These passages translated by Richard Jonathan.

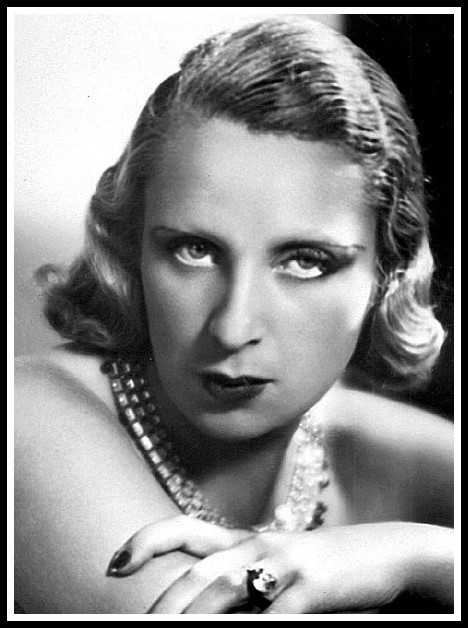

Tamara de Lempicka in the 1930s

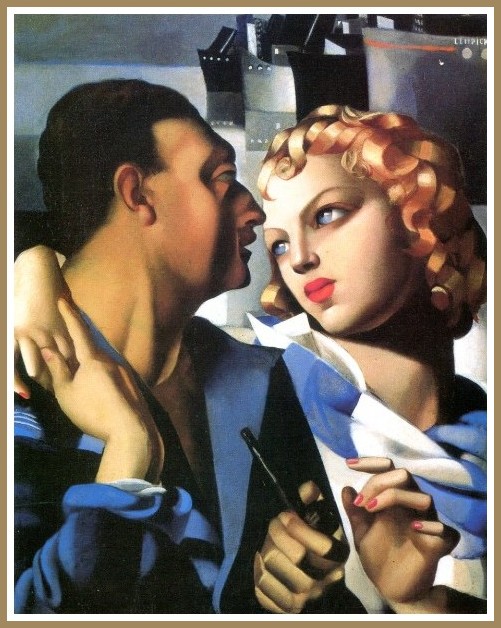

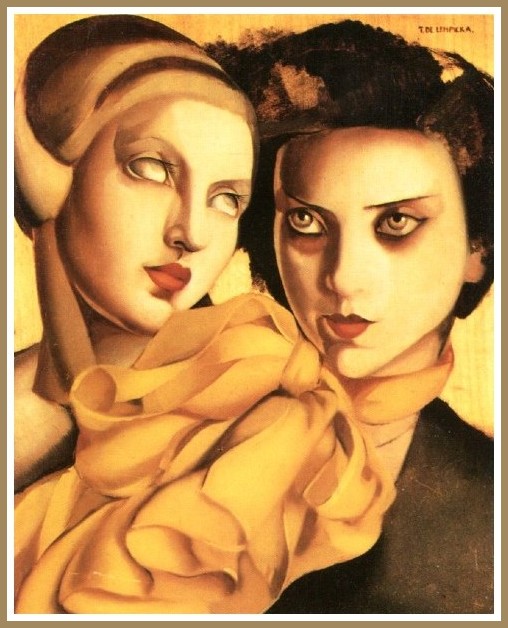

Early in the 20th century, in the period 1910-1930, the ‘artist as body’ appeared. Examples include Tamara de Lempicka, whose very Art Déco aesthetic manifests itself with a rare meticulousness in her highly flamboyant portraits that evoke, with their distant echo of the Pre-Raphaelites, characters—both masculine and feminine—whose silhouettes and poses are very dandyish.

It is from Baudelaire, in literature, and Kierkegaard, in philosophy, that the definition of art as art comes into effect, no longer regarding only the work of art but the artist himself—or better still, his life—as a work of art. And thus emerged, in terms of aesthetics, a new theme practically unknown until then: lifestyle as an art form, if not a full-blown work of art. This is the primary characteristic of dandyism.

This way of making art and life coincide, or more exactly, of elevating life’s pleasures to the level of artistic beauty—its supreme value as much as its intrinsic dignity—is of course what Oscar Wilde advocated in The Picture of Dorian Gray. Indeed, he has Lord Henry say, for example, ‘now and then a complex personality took the place and assumed the office of art, was indeed, in its way, a real work of art’. Directly echoing this, Wilde, in Chapter 11 of the novel, enlarges at length on the luxurious, refined and cultivated life led by the young Dorian Gray: ‘And, certainly, to him life itself was the first, the greatest, of the arts, and for it all the other arts seemed to be but a preparation.’

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA & DANDYISM (II)

IIa. Mythologizing the Self

Richard Jonathan

Tamara de Lempicka, Salvador Dali and Leonor Fini constitute a trio of the 20th-century’s top ‘dandy-artists’, defined as artists who adopt a stance toward themselves and the world that enables them to nurture their individuality, their ‘secret self’, under cover of the persona they project into the world. For the dandy, as for the clown, what they reveal is designed to conceal.

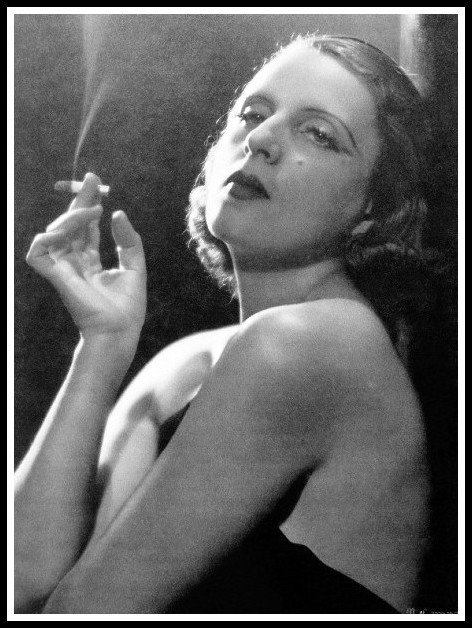

Tamara de Lempicka, c.1935

Beyond the apparent flamboyance of these artists, then, one has to be sensitive to their ‘secret self’ to gain a fuller appreciation of the ‘personality’ expressed in the work. In other words, one must endeavour to understand how the life and the work interact in the mythologizing of the self.

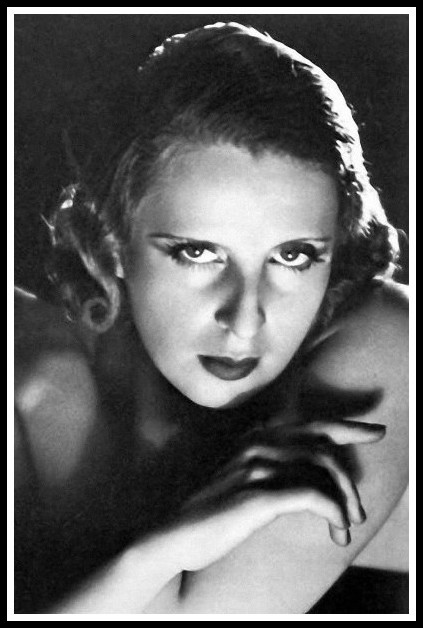

Tamara de Lempicka in the 1930s

IIb. Tamara de Lempicka and Salvador Dali

Laura Claridge

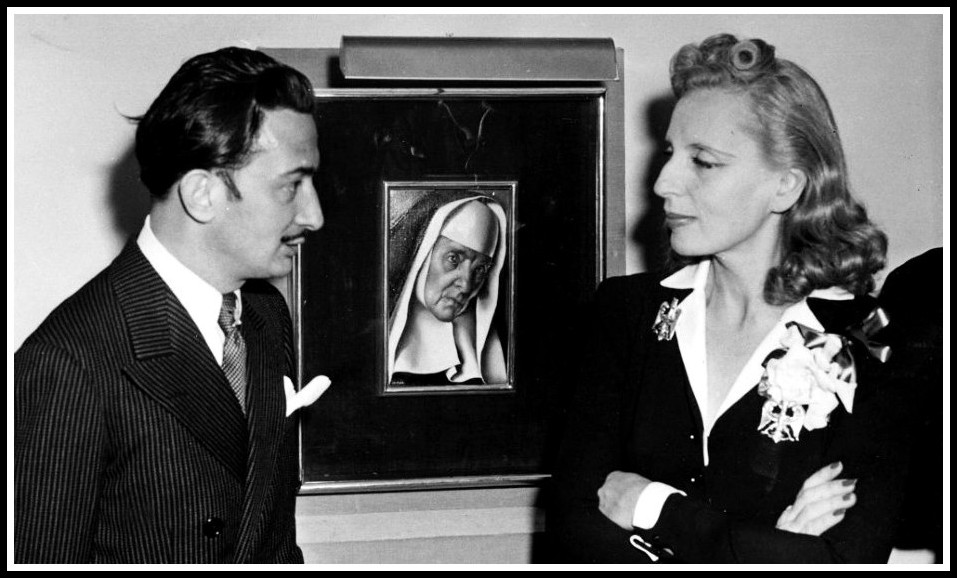

Though in France Surrealism had won the battle for the avant-garde by the late 1920s, it was still struggling to gain a stronghold in America during the war years, and Tamara, who during her early years in the United States had executed several fairly successful Surrealistic paintings, might have done well to continue in that direction. Her quick wit and pleasure in the absurd, mentioned repeatedly by her friends, lent themselves to the genre, and those same qualities won her the loyalty of Salvador Dali, one of the few artist friends from Paris whom she continued to see in America. His 1934 painting Enigma of William Tell depicted Lenin’s exposed buttocks with a giant phallus (parodying a rocket) inserted between his thighs. Deeply offended by the insult to one of their heroes, other Surrealists were thereafter suspicious of Dali’s politics, further strengthening Tamara’s conviction that Dali was worth taking seriously.

From Laura Claridge, Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence (London: Bloomsbury, 2000) p. 222

Salvador Dali and Tamara de Lempicka, New York City, 1941

IIc. Tamara de Lempicka and Leonor Fini

Laura Claridge

The two friends [Tamara de Lempicka and Victor Contreras] talked of art, with Tamara expressing her enthusiasm for Leonor Fini, the Argentine painter living in Mexico City.

From Laura Claridge, Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence (London: Bloomsbury, 2000) p. 327

Leonor Fini, Bal du Panache, Paris 1947

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA & DANDYISM – III

Laura Claridge

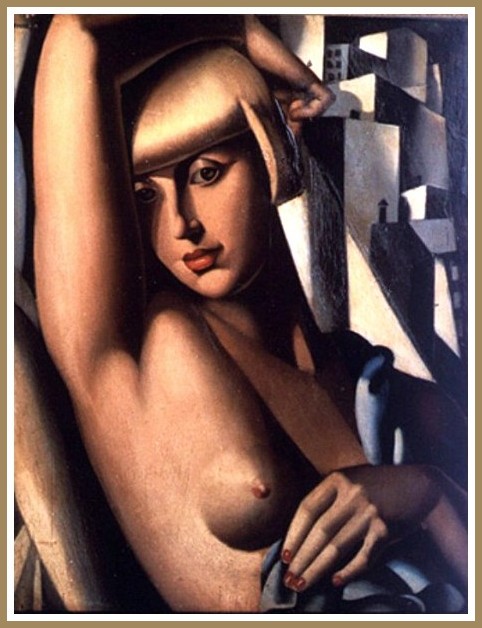

Named by her mother for the heroine of one of Mikhail Lermontov’s poems, either Tamara or The Demon, she fit the expectations that both comparisons to passionate women suggested. Sexually voracious, theatrical, stylish, smart, and talented, she was among the century’s most dramatic and imposing personalities. Whether it be her careless sexual affairs with any man or woman she considered beautiful, her glamorous parties, complete with drugs and naked servers, or her refusal to provide information about her past, the aura of decadence that came naturally to her ensured that she played always at center stage.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of Ira P., 1930

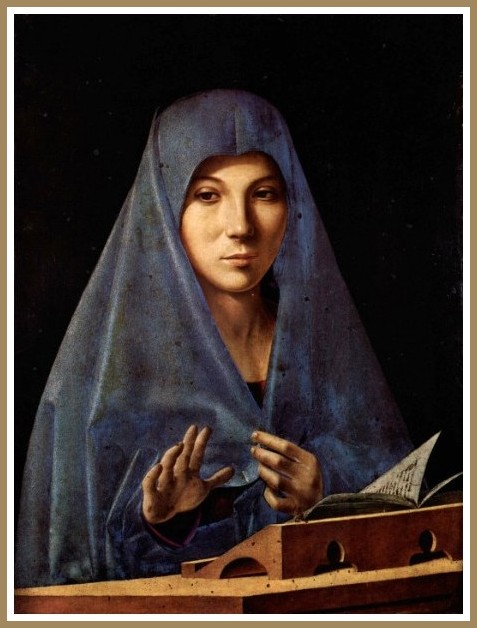

Although her paintings of the 1920s had helped create the image of the modern woman, Marie Antoinette’s sense of entitlement, order, and self-indulgence were every bit as much a part of Tamara’s character as twentieth-century values were. Her complexity extended to her painting; perhaps that is why she was neglected by those who defined the Modernist canon. She painted in iconoclastic, dramatically modern styles, while she also pledged allegiance to Giovanni Bellini, Pontormo, Antonello da Messina, and Caravaggio, in color and in brushstroke. She boldly painted the nude female with a lover’s eye, yet she refuted classification by gender. She refused to court the avant-garde but defiantly participated in café society, even when it was clear that such frivolous associations caused other artists to underrate her talent.

Tamara de Lempicka, Sleeping Woman, 1930

In life and in her work, she did not play with the idea of depth versus surface. And it is here that she fits, after all, within Modernism’s boundaries. But art historians have failed to note when rejecting Tamara from their definitions of Modernism that her high artifice rehearses a major Modernist tenet. This artifice consists of a narcissism so extreme that it becomes its own subject, constituting in the process a self-contained, self-referential painterly sphere.

From Laura Claridge, Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence (London: Bloomsbury, 2000) pp. 2-3

Tamara de Lempicka, Les Jeunes filles, 1930

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA & DANDYISM (IV)

Tamara de Lempicka and Greta Garbo

Laura Claridge

Tamara’s proudest social conquest was her rapidly developing friendship with her idol, Greta Garbo; she claimed to have played tennis with her, though no one can recall Tamara being much of a player. For the next three years, however, she referred to Garbo so frequently that the actress seemed to be a fixation for the painter. She announced to the press that she was doing Garbo’s portrait, but none has been located. The physical resemblance that hotel guests had supposedly seen between the two women seven years earlier predisposed Tamara to admire the actress, and the parts she had played further impressed her. In 1935, Garbo starred in Anna Karenina; in 1937 she played opposite Tamara’s friend Charles Boyer as Napoleon, the artist’s hero, in Conquest; and in 1939 she starred in Ninotchka, a satire on Bolshevism that delighted the painter.

Perhaps she mentally projected herself into Garbo’s place.

Material for such a fantasy was close at hand in the form of a sketch she had done of Charles Boyer in 1930. Since Tamara rarely painted from a photograph, preferring to work with the live model, she must have known Boyer at least ten years before she moved to Hollywood.

Pictures of the two [Charles and Tamara] on the Hollywood sets of the early forties show them with intimate, almost smirking smiles, suggesting that they were already well acquainted.

From Laura Claridge, Tamara de Lempicka: A Life of Deco and Decadence (London: Bloomsbury, 2000) pp. 223

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA & DANDYISM (V)

Dandyism in the age of Mass Culture: Susan Sontag on Camp

Selections from Susan Sontag, ‘Notes on Camp’ in Against Interpretation (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1966)

Camp is a certain mode of aestheticism. It is one way of seeing the world as an aesthetic phenomenon. That way, the way of Camp, is not in terms of beauty, but in terms of the degree of artifice, of stylization. Camp is a vision of the world in terms of style—but a particular kind of style. It is the love of the exaggerated, the ‘off,’ of things-being-what-they-are-not. The best example is in Art Nouveau, the most typical and fully developed Camp style. Art Nouveau objects, typically, convert one thing into something else: the lighting fixtures in the form of flowering plants, the living room which is really a grotto. A remarkable example: the Paris Métro entrances designed by Hector Guimard in the late 1890s in the shape of cast-iron orchid stalks. A full analysis of Art Nouveau would scarcely, of course, equate it with Camp. But such an analysis cannot ignore what in Art Nouveau allows it to be experienced as Camp. Art Nouveau is full of ‘content,’ even of a political-moral sort; it was a revolutionary movement in the arts, spurred on by a Utopian vision (somewhere between William Morris and the Bauhaus group) of an organic politics and taste. Yet there is also a feature of the Art Nouveau objects which suggests a disengaged, unserious, ‘aesthete’s’ vision. This tells us something important about Art Nouveau—and about what the lens of Camp, which blocks out content, is.

Victor Horta, Interior of Hôtel Tassel, 1894

As a taste in persons, Camp responds particularly to the markedly attenuated and to the strongly exaggerated. The androgyne is certainly one of the great images of Camp sensibility. Examples: the swooning, slim, sinuous figures of pre-Raphaelite painting and poetry; the thin, flowing, sexless bodies in Art Nouveau prints and posters, presented in relief on lamps and ashtrays; the haunting androgynous vacancy behind the perfect beauty of Greta Garbo. Here, Camp taste draws on a mostly unacknowledged truth of taste: the most refined form of sexual attractiveness (as well as the most refined form of sexual pleasure) consists in going against the grain of one’s sex. What is most beautiful in virile men is something feminine; what is most beautiful in feminine women is something masculine. Allied to the Camp taste for the androgynous is something that seems quite different but isn’t: a relish for the exaggeration of sexual characteristics and personality mannerisms.

Camp sees everything in quotation marks. It’s not a lamp, but a ‘lamp’; not a woman, but a ‘woman.’ To perceive Camp in objects and persons is to understand Being-as-Playing-a-Role. It is the farthest extension, in sensibility, of the metaphor of life as theater. Camp is the triumph of the epicene style. (The convertibility of ‘man’ and ‘woman,’ ‘person’ and ‘thing.’) But all style, that is, artifice, is, ultimately, epicene. Life is not stylish. Neither is nature.

The hallmark of Camp is the spirit of extravagance. Camp is a woman walking around in a dress made of three million feathers. Camp is the paintings of Carlo Crivelli, with their real jewels and trompe-l’oeil insects and cracks in the masonry. Camp is the outrageous aestheticism of Steinberg’s six American movies with Dietrich, all six, but especially the last, The Devil Is a Woman. In Camp there is often something démesuré in the quality of the ambition, not only in the style of the work itself. Gaudí’s lurid and beautiful buildings in Barcelona are Camp not only because of their style but because they reveal –most notably in the Cathedral of the Sagrada Familia—the ambition on the part of one man to do what it takes a generation, a whole culture to accomplish.

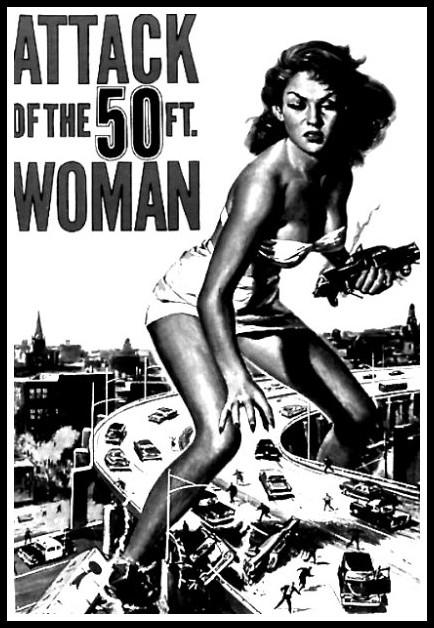

Detachment is the prerogative of an elite; and as the dandy is the 19th century’s surrogate for the aristocrat in matters of culture, so Camp is the modern dandyism. Camp is the answer to the problem: how to be a dandy in the age of mass culture. The dandy was overbred. His posture was disdain, or else ennui. He sought rare sensations, undefiled by mass appreciation. (Models: Des Esseintes in Huysmans’ À Rebours, Valéry’s Monsieur Teste.) He was dedicated to ‘good taste.’ The connoisseur of Camp has found more ingenious pleasures. Not in Latin poetry and rare wines and velvet jackets, but in the coarsest, commonest pleasures, in the arts of the masses. Mere use does not defile the objects of his pleasure, since he learns to possess them in a rare way. Camp—dandyism in the age of mass culture—makes no distinction between the unique object and the mass-produced object. Camp taste transcends the nausea of the replica.

Hertz-Juran, Attack of the 50-Foot Woman, 1958

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Intermezzo 1: Lilo

We speak of women artists, we find we share a love for Frida Kahlo, Tamara de Lempicka, Remedios Varo.

Tamara de Lempicka, Portrait of Suzy Solidor, 1933

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA: FRAMING FEMININITIES

Paula Birnbaum

From Paula Birnbaum, Women Artists in Interwar France: Framing Femininities (London: Routledge, 2016)

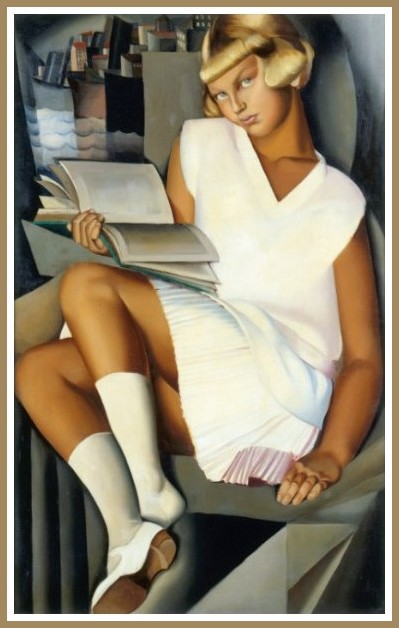

De Lempicka’s portrayal of her daughter in Kizette on the Balcony is a mother’s meditation on her child’s sexuality and may allude to her identification with her daughter’s feelings about impending puberty. Kizette, who was eleven years old when she modeled for this work, is portrayed sitting in a chair beside a balcony that overlooks a dramatic metropolitan skyline. Her body awkwardly fills the entire length of the picture plane. The top of her head is cut off at one end, and her pigeon-toed feet, signifying childishness, are crammed in at the bottom right corner of the other end. Her neck is turned oddly to one side, and her posture is maladroit. While Kizette’s short, tunic-style gray dress blends in with the muted tones in the composition, it also calls attention to her tubular, flesh-toned thighs that emerge from underneath the garment. The smooth, contoured quality of this exposed portion of the girl’s shapely legs is disrupted at mid-calf, where stark white knee socks and black patent-leather shoes remind the viewer of the model’s youth and innocence.

Tamara de Lempicka, Kizette on the Balcony, 1927

In spite of such youthful references, however, de Lempicka’s emphasis upon her daughter’s awkward bodily pose and unclothed thighs is provocative. The question of the artist’s eroticized perspective is complicated, given her refusal to identify her model as her own daughter. On the other hand, our knowledge of their relationship suggests the mother-artist’s possible identification with her daughter-model as a younger image of herself that recalls the experience of her own sexual awakening. As for her facial expression, Kizette’s head is tilted awkwardly to one side, calling attention to the strained position of her neck and her heavily lidded steel-grey eyes that confront the viewer directly. Her lips are sensually pursed and painted in de Lempicka’s usual artificial red, and her short blonde hair hangs in an alluringly tousled manner. [Below: another painting of Kizette.]

Tamara de Lempicka, Kizette in Pink, c.1926

Kizette’s right hand is idly posed in her lap. Her left one grasps the iron ledge of the balcony, perhaps suggesting her position in life, close to the threshold of adulthood, as symbolized by the exterior world of the harsh, angular cityscape. It seems de Lempicka was struck by her daughter’s awkward position as a girl about to experience the physical and emotional changes that accompany puberty. Her portrait emphasizes her daughter’s impending sexuality and would appeal to an audience that appreciated erotic portraiture for public consumption. De Lempicka’s portrait of Kizette shows us how maternity could complicate an artist’s sense of her professional identity and legacy, posing questions about her own sexuality and embodiment as well as that of her young daughter. [Below: another painting of Kizette.]

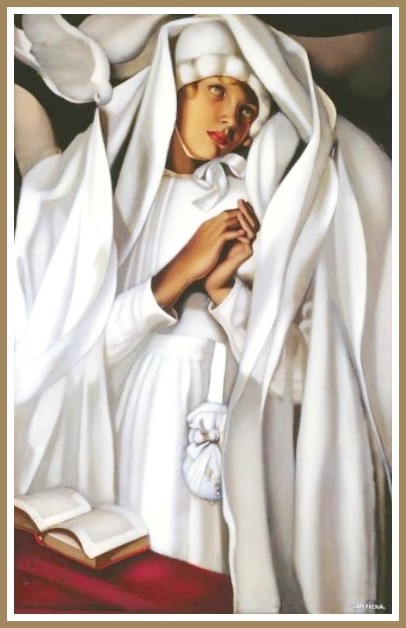

Tamara de Lempicka, First Communion, 1928

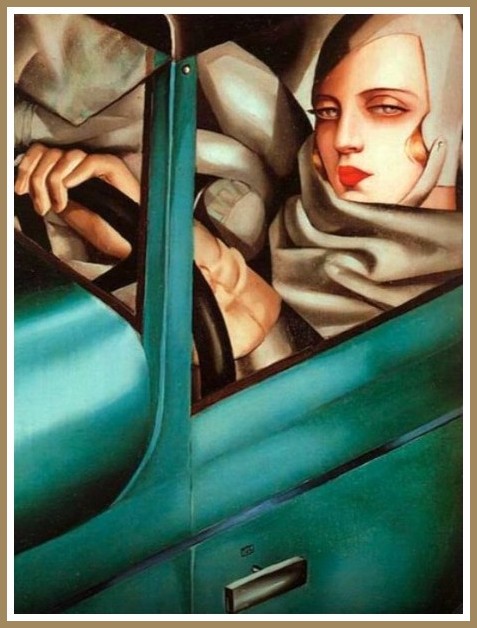

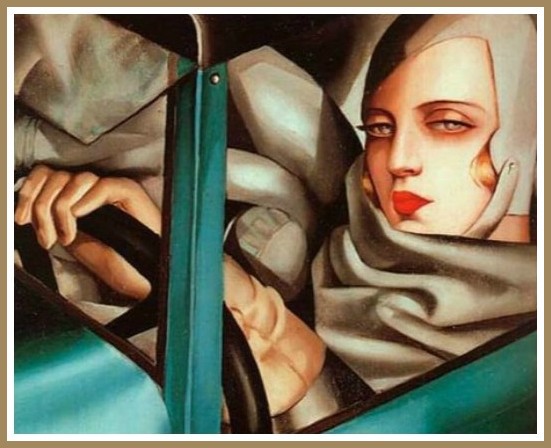

Tamara de Lempicka’s Self-Portrait of 1929 appeared on the cover of the German fashion magazine Die Dame, and although it was not exhibited directly with the group, it also serves as an important symbol of the masquerade and the contradictions faced by many female artists associated with this group in orchestrating their self-representations. In this painting, de Lempicka chose to represent herself in the driver’s seat of a shiny green Bugatti sports car, clad in a fashionable racing cap, leather gloves, and billowing gray scarf. Through her appropriation of imagery that connotes the wealth and power that remained inaccessible to most real women, she stakes a claim to a specific kind of female modernity.

Tamara de Lempicka, Self-Portrait (Tamara in the Green Bugatti), 1929

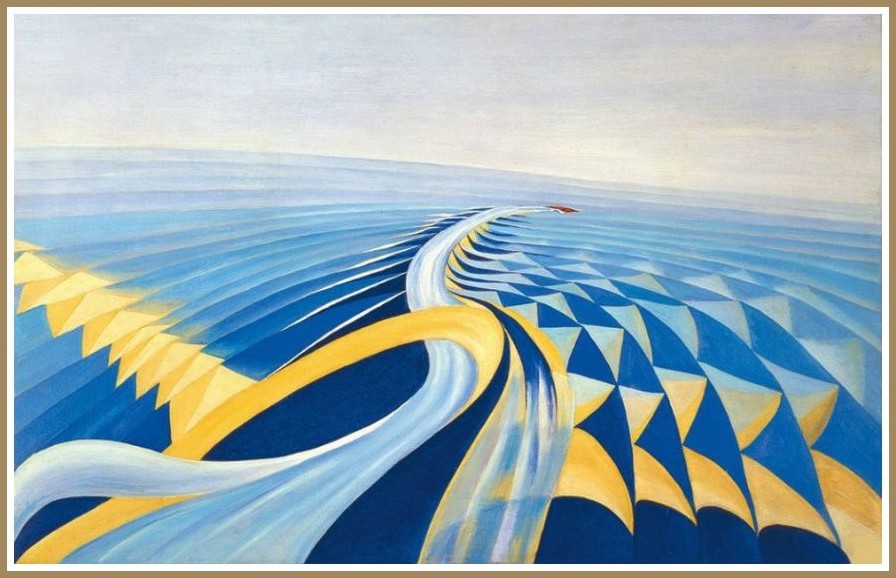

De Lempicka pays homage to the machine-based modernist aesthetic of the Italian futurist Filippo Marinetti, whom she met in Paris in 1924, some fifteen years after his famous Futurist Manifesto celebrated ‘the beauty of speed’ and the birth of a revolutionary movement.

Benedetta Cappa Marinetti, Speeding Motorboat, 1923–24

The metallic-colored leather cap, single leather glove, and arresting scarf adorning the artist appear to be adapted from men’s racing or flying clothes, suggesting her choice to connect herself to fashionable images of affluent women who could afford to enjoy male-dominated pastimes. She depicts her own facial features as mannequin-like; the large, heavily lidded eyes, thinly arched brows, straight nose, and bright red lips promote the look of modern femininity typical of fashion advertising of the period. By choosing to represent herself in the driver’s seat of a car, de Lempicka played to the link between the elite garçonne image and the new consumer culture.

Tamara de Lempicka, Self-Portrait (Tamara in the Green Bugatti), 1929 (detail)

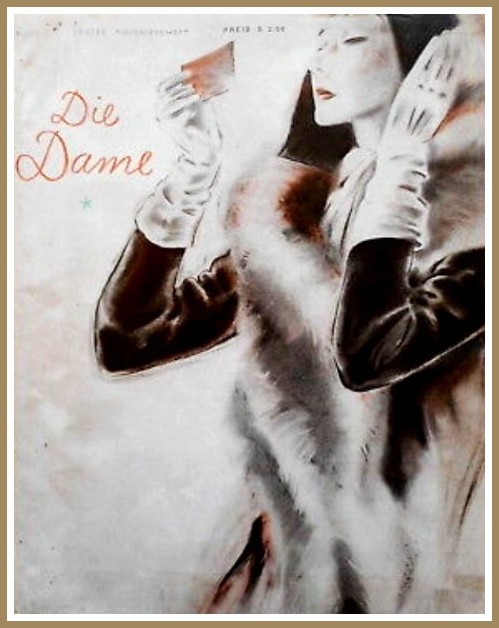

The editor of Die Dame in fact commissioned the self-portrait after she encountered the nearly divorced de Lempicka behind the wheel of what was actually a yellow Renault (while de Lempicka was vacationing in Monte Carlo). It appeared on the cover of the magazine in 1929 to promote the German ideal of the modern woman, who in this case happened to be a professional painter. For all of the seductive qualities of this image of female modernity, de Lempicka’s 1929 Self-Portrait also conveys a strong sense of physical containment and repression that leaves the viewer questioning the ultimate message. The deformation of the female body in this painting appears to be an integral part of the artist’s commodification of the modern woman image in an age of rising industrialism.

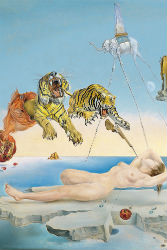

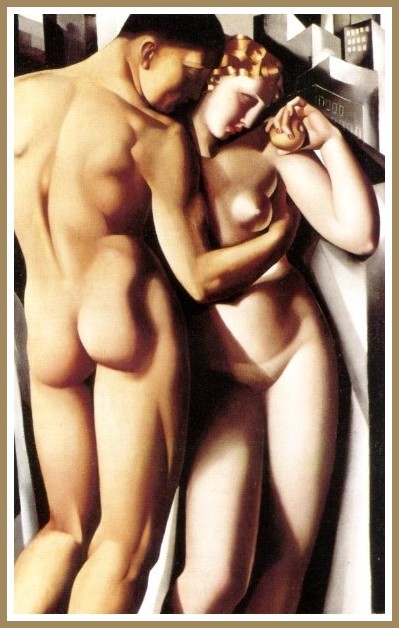

Ernst Dryden, Die Dame, February 1929

Tamara de Lempicka, in her 1931 Adam and Eve, radically modernizes the biblical theme. She positions her nude figures in a physical embrace before a steel-colored, post-cubist cityscape. Adam’s muscular forearm wraps around Eve’s ribcage and grazes the underside of her breast. A flesh-toned apple in Eve’s elevated hand is the only remnant of paradise here—its spherical shape echoed in the single breast exposed below—suggesting the implicit connection between Eve’s sexuality and the fruit of knowledge. De Lempicka strategically employs a close-up perspective that suggests that the sexual energy inspired by her figures’ youthful bodies can hardly be contained by the parameters of the picture plane. Their smooth, athletic-looking physiques are carefully modeled and brightly illuminated to emphasize the physical attractiveness they offer to each other as well as to the viewer. The rippling musculature of Adam’s back, buttocks, thighs, and upper arm swells with vitality and power; de Lempicka seems intent to eroticize his body. She turns Adam’s back to the viewer to avoid representation of his genitals, while still eroticizing his body through the exaggeration of musculature. She also poses Eve seductively; bright frontal lighting draws attention to her single exposed breast with erect red nipple at its center, its spherical shape evocative of modern machinery. Her arm appears plumply sensuous and lacks the muscular definition of Adam’s, whereas her fingers are carefully delineated by the application of bright-red nail polish that echoes the color of her painted lips and exposed nipple.

Tamara de Lempicka, Adam and Eve, 1932

De Lempicka often applied bright red paint to highlight the lips, nipples, and fingernails of her female nudes—perhaps as a means to titillate her viewers with the look of modern femininity.

Tamara de Lempicka, Idyll, 1931

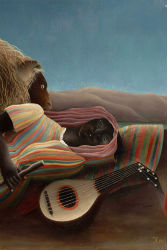

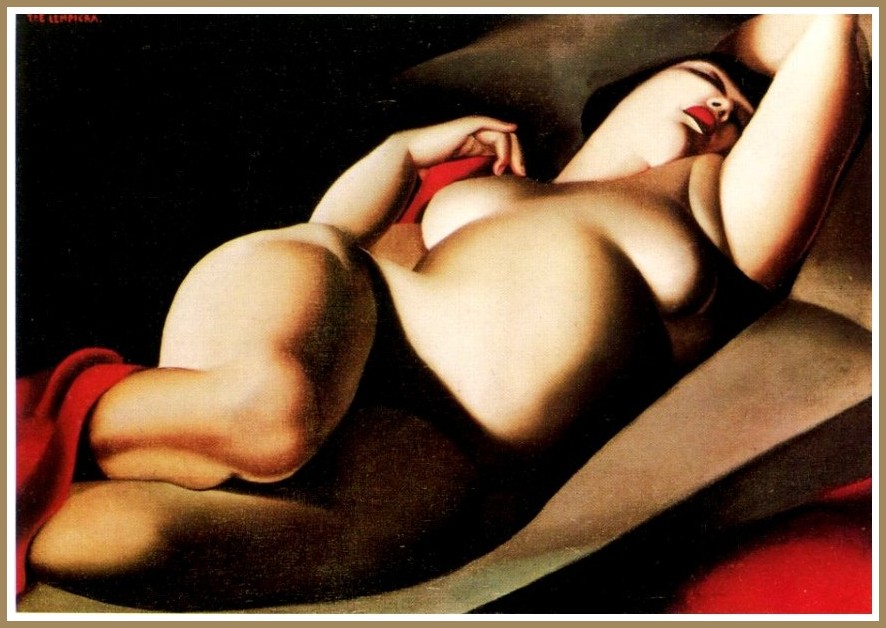

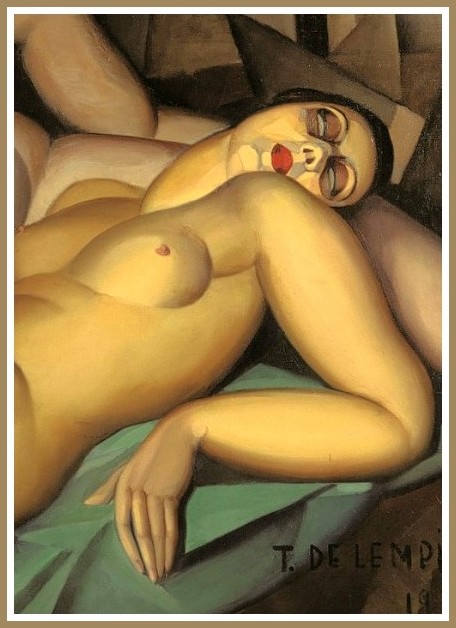

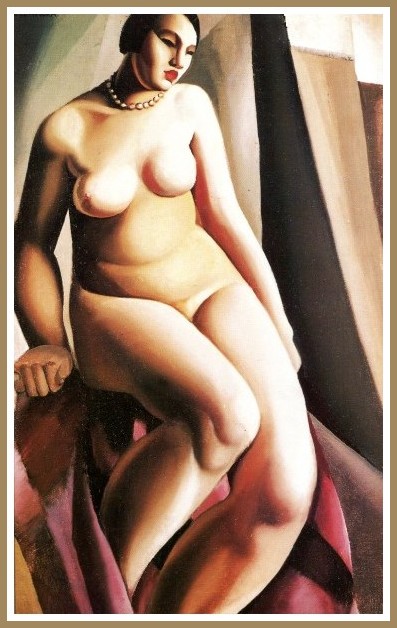

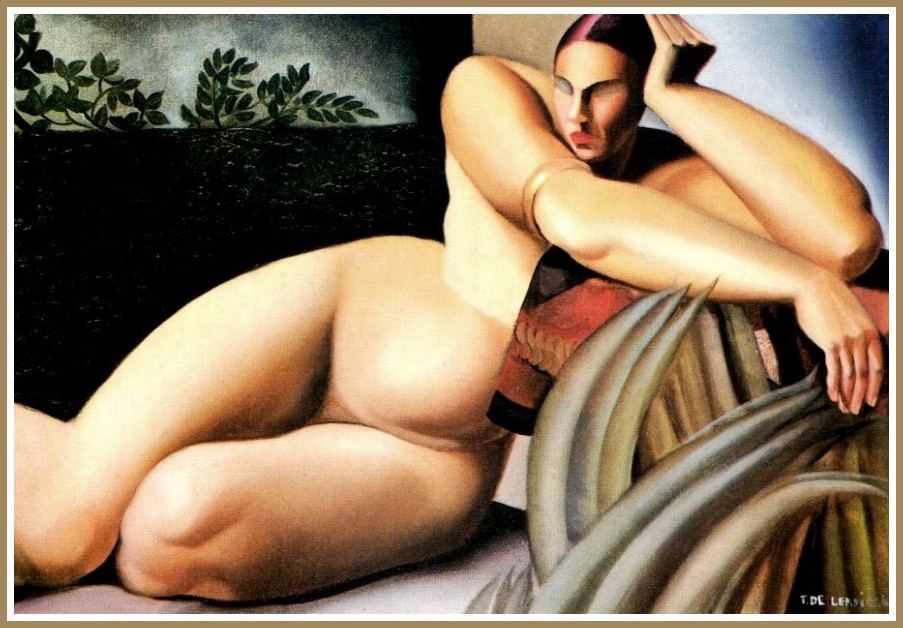

La Belle Rafaela, de Lempicka’s painting of a voluptuous female bather, strategically plays to the Western conventions of the odalisque, or languidly reclining and sexually available inhabitant of a harem. With eyes closed, full red lips parted, and one arm posed provocatively behind her head, the model solicits our gaze even while she appears fully self-absorbed. While the lighting accentuates the figure’s distended face, neck, breasts, and abdomen, a shadow is cast horizontally across the lower midriff, strategically obscuring the pubic area from view. To heighten the viewer’s experience of her model’s curvaceous physique, de Lempicka has reduced the background composition to basic geometric planes of black, gray, and red tones. She has chosen to crop her subject further by concealing the model’s lower calves, ankles, and feet with a plush red blanket whose color echoes the shade of lipstick that covers her swollen upper lip. The alluring red fabric disappears behind the model’s right calf, re-emerging in the awkwardly painted space between her right hand and illuminated breast. Here, in a gesture of self-absorbed pleasure, the model awkwardly extends two thick fingers to graze the top portion of her breast. De Lempicka angles her model’s legs so as to give the viewer access to her pubic area. It is as if the viewer were in the process of moving directly onto the nude’s ample body, confronting her, dead-on and from the same level, in a sexually charged manner. De Lempicka uses perspective here to claim explicitly the fantasy of sexual control from a female perspective. She appears to have invited her viewers, female or male of whatever sexual orientation, into bed with her model, Rafaela. Her representation of Rafaela’s body is a case where an artist’s act of looking is split between sexual objectification and narcissistic identification, revealing the artist’s recognition of what it means to be both desired and objectified as a woman and to desire other women.

Tamara de Lempicka, La Belle Rafaela, 1927

[Another painting of Rafaela]

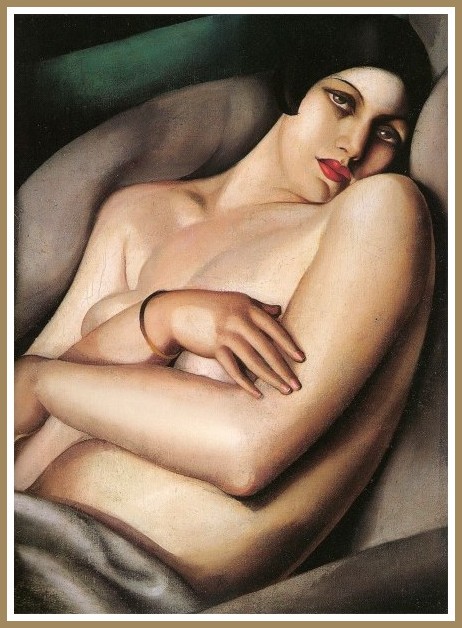

Tamara de Lempicka, The Dream (Rafaela), 1927

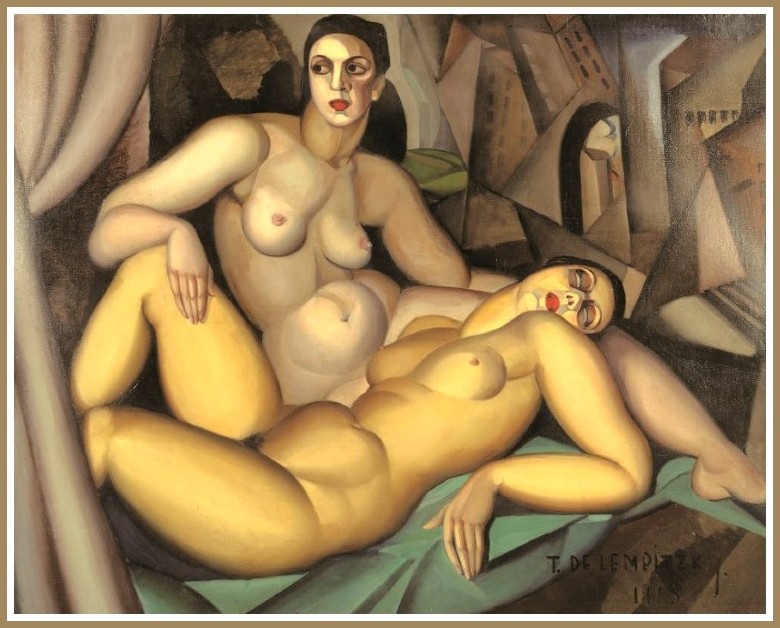

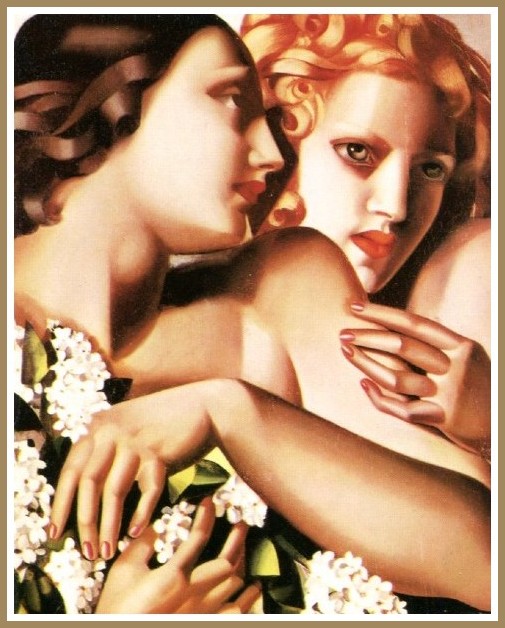

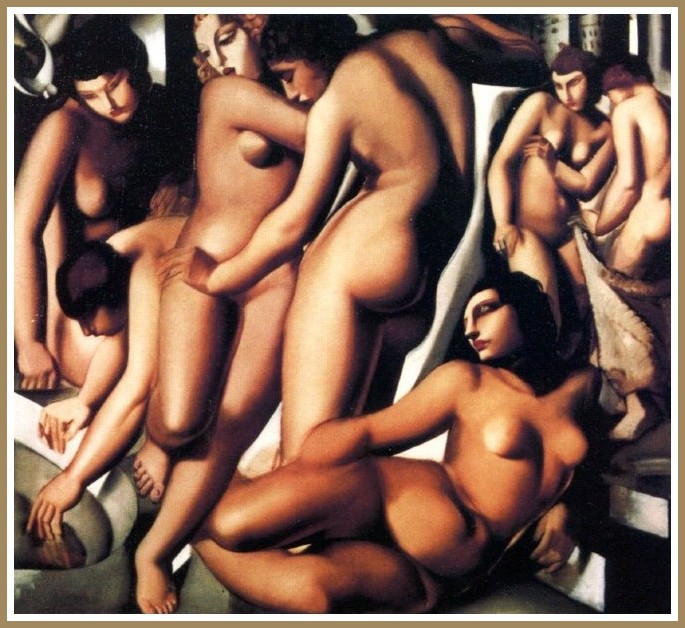

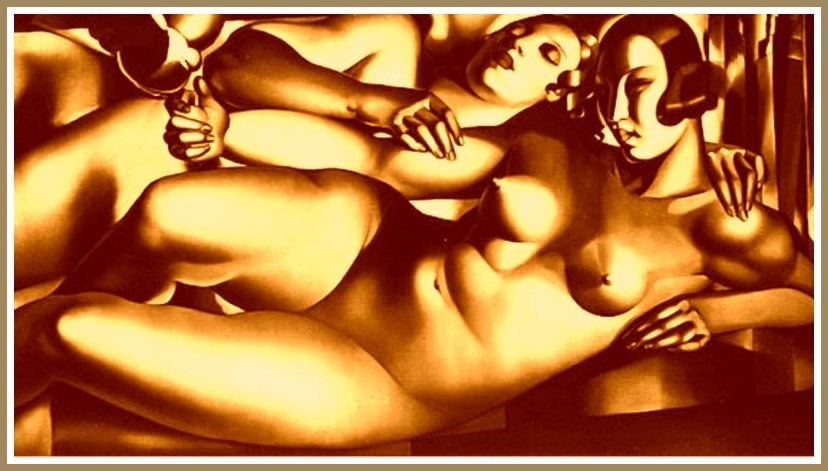

In de Lempicka’s Two Friends, one woman reclines on her back, in the self-absorbed manner of La Belle Rafaela, against the extended legs of her seated companion. The seated woman, in turn, comfortably rests her hand upon the reclining woman’s inner thigh, which reveals a hint of dark pubic hair. This provocative posing of two nude female figures together makes an appeal for the representation of the modern lesbian couple as a counterpart to Adam and Eve. The women are portrayed during a moment of intimate exchange in a secluded homo-social space, perhaps an allusion to a 1920s Parisian bathhouse or brothel, where lesbian sexual contact would have been possible. De Lempicka’s references to the modern metropolis in the background appear fantastic. The cubist-style buildings are even more strangely fractured and abstract than in Adam and Eve, and the background looks cavernous and sinister. The theatrical quality of the painting is reinforced by the artist’s placement of a plush, emerald-green fabric underneath the figures, and a gray, velvet curtain beside them.

Tamara de Lempicka, Two Friends, 1923

What is striking about de Lempicka’s Two Friends is the artist’s frank manner of representing same-sex desire in terms easily recognized by her audience. By the mid-1920s, the Parisian public was familiar with the concept of the third sex, the popular cultural image of the homosexual or lesbian as an in-between, androgynous figure. Well-known European sexologists like Havelock Ellis, Magnus Hirschfeld, and Richard Krafft-Ebing developed the definition. In de Lempicka’s painting, the models’ faces have the look of the 1920s garçonne—here a symbol of the third sex—with cropped, dark hair and full, red lips. Their heads rest upon broad-shouldered, muscular, small-breasted bodies. Throughout European capitals such as Paris and Berlin, this type of popular image became part of the pseudo-scientific discourses about sex and gender. De Lempicka appears to have imbued the modern woman with sexual expressiveness and agency. Female nudity and intimate contact between female companions would have resonated with an audience open to understanding lesbianism.

Tamara de Lempicka, Two Friends, 1923 (detail)

De Lempicka’s Two Friends also reveals her interest in pushing the limits of naturalism as a means to challenge associations between sexuality, deformity, and the female body. The women’s intertwined bodies appear contorted, their figures full of strange recesses and swellings—for example, at the waistlines of both women. It looks as if an invisible thread has been tightly fastened around each model’s waist, severing her body into two separate pieces. De Lempicka has differentiated their skin tones, with the reclining model’s yellowish-orange complexion a contrast to her fairer partner’s. The erect nipples on their cylindrical breasts suggest the models’ sexual arousal. A mask of grayish purple shadow eerily blocks the eyes of the reclining model, and her partner’s expression is vacant. While historically the genre of the female nude has served as the commodity of patriarchal culture, de Lempicka has succeeded here in transforming it into an image of female sensual pleasure.

Tamara de Lempicka, Two Friends, 1923 (detail)

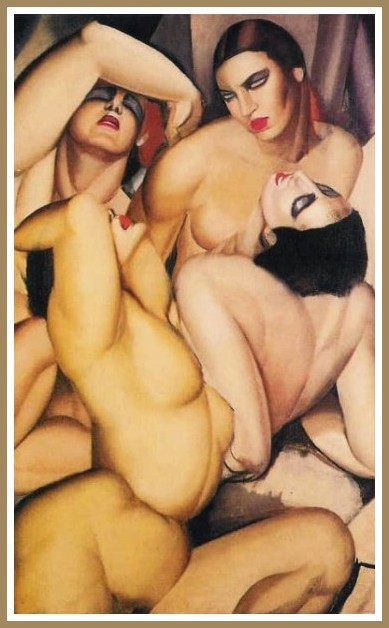

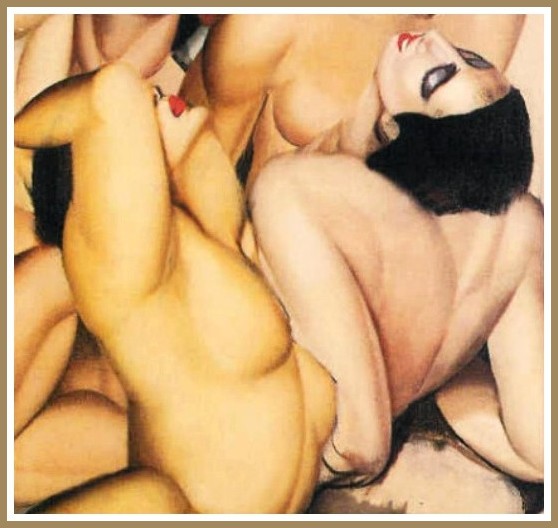

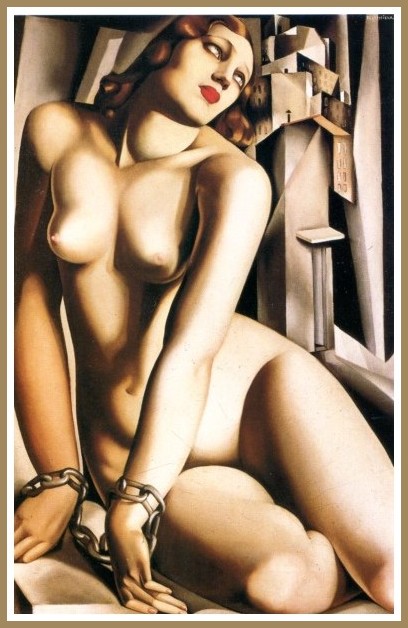

In the more explicit Group of Four Nudes, de Lempicka took her transformation of the odalisque genre several steps further. The interconnected bodies of the women in this orgiastic image seem to exaggerate and multiply the contortion of The Two Friends, further emphasizing the connections between sexual pleasure and pain among a group of naked women.

Tamara de Lempicka, Group of Four Nudes, c.1925

To understand the traditions to which de Lempicka was responding, many critics have compared this painting to Ingres’s celebrated The Turkish Bath of 1862, with its erotic display of the exoticized and multiplied female nudes in a harem.

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, The Turkish Bath, 1852/59/62

De Lempicka’s use of an even closer viewpoint and more severely cropped frame may be what earned her the reputation of the perverse Ingres. In her harem painting, as in La Belle Rafaela, we are invited to participate, in this case in the carnal pleasures of an exclusively female bathhouse or brothel. The perversity of de Lempicka’s gesture—for a contemporaneous critic like Arsène Alexandre—lies in the fact that as a female artist, she dares to represent the fantasy of her own desire for the inflated, multiplied female bodies that writhe here in hedonistic pleasure, enhanced by the pain suggested by their severe fragmentation. One of the women in Group of Four Nudes is portrayed in the midst of orgasm, her twisted body writhing in the moment of self-absorbed pleasure. It is this ability to give visual form to women’s sexual experiences that makes de Lempicka’s work so compelling. Surely, she was also aware that images of women engaged in sexual acts with one another are a staple of male heterosexual fantasy.

Tamara de Lempicka, Group of Four Nudes, c.1925 (detail)

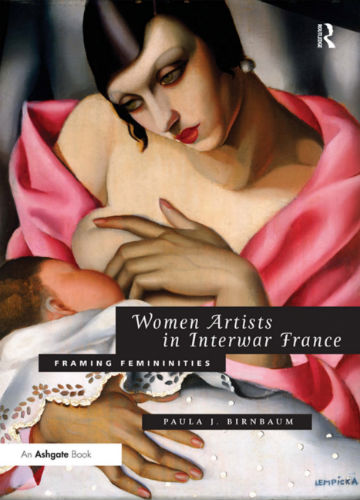

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA: THREE BOOKS

LAURA CLARIDGE

Tamara de Lempicka: Deco and Decadence

PAULA BIRNBAUM

Women Artists in Interwar France

GIOIA MORI

Tamara de Lempicka: Queen of Modern

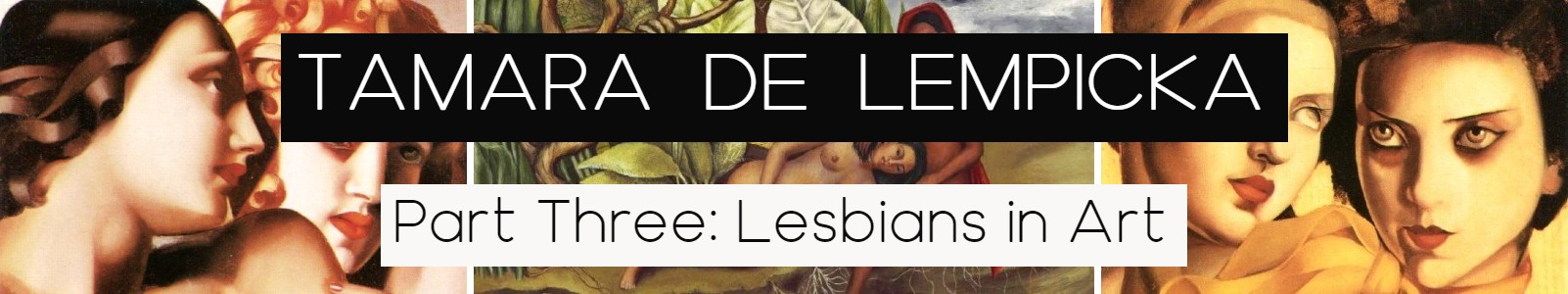

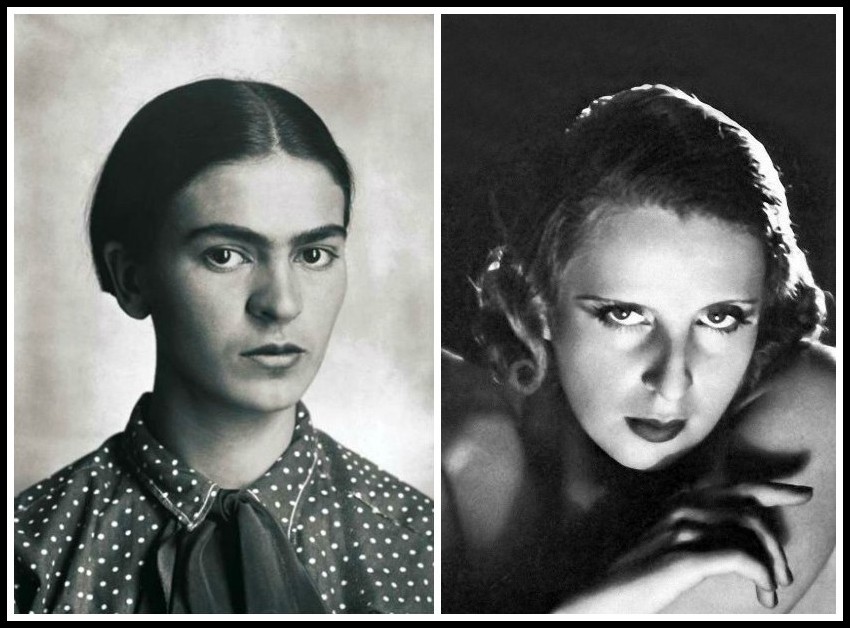

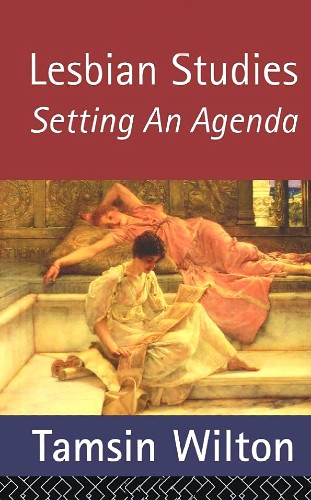

LESBIANS IN ART (I): WHAT DO WE MEAN?

Tamara de Lempicka & Frida Kahlo

Tamsin Wilton

From Tamsin Wilton, Lesbian Studies: Setting an Agenda (Routledge, 1995) pp. 143-144

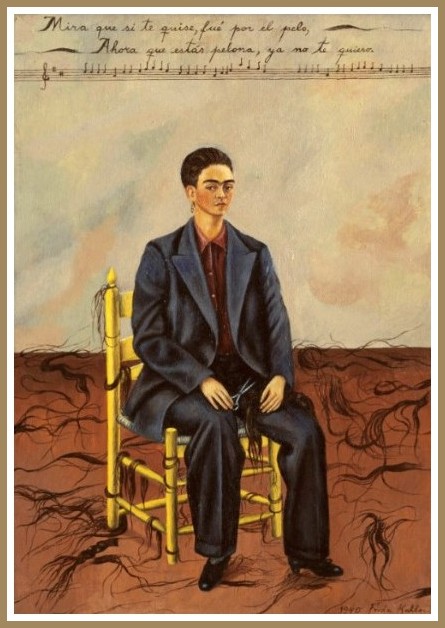

Research waits to be done on the meaning(s) of lesbian in the work of Frida Kahlo and Tamara de Lempicka. There could not be two more different women. Kahlo was committed to the Mexican Revolution and she once took Trotsky as her lover. Lempicka was a baroness, a refugee from the Russian Revolution and decadent doyenne of Paris and New York society. Both were apparently bisexual, but desire for women is given very different meanings in their work.

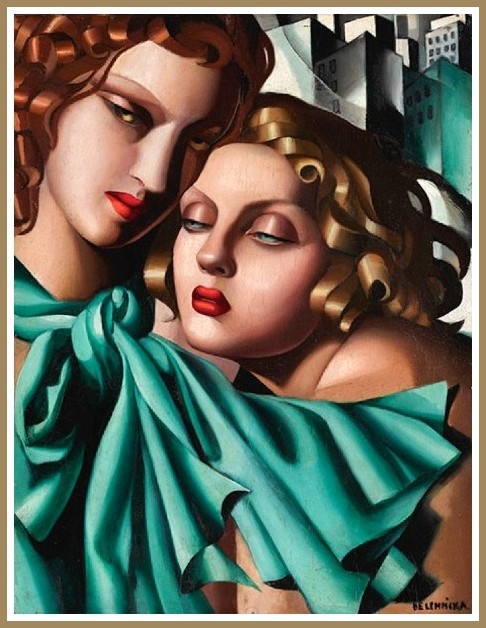

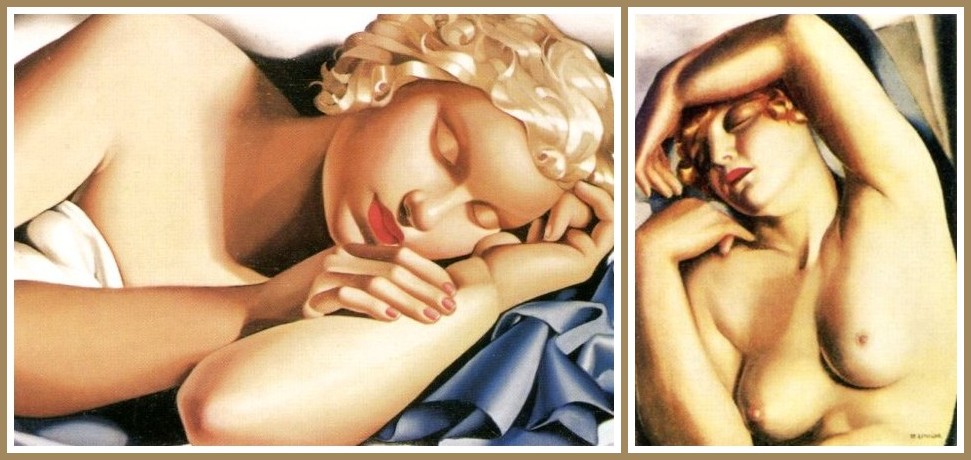

Frida Kahlo | Tamara de Lempicka

For de Lempicka, an Art Deco painter who flirted with Cubism and Surrealism, lesbian love becomes an integral part of the decadent lasciviousness (in her life as much as her art) for which she was nicknamed ‘a perverse Ingres’. De Lempicka’s ‘lesbian’ has much in common with the ‘lesbian’ of Baudelaire, Louys or Renée Vivien—a lost creature, tortured with insatiable lusts, heavy eyed with lack of sleep and sexual over-indulgence—and she painted many such creatures.

Tamara de Lempicka, The Young Ladies, 1927

Kahlo painted mostly self-portraits, and only a few lesbian images—‘What I Saw in the Water’, for example, or ‘Two Nudes in the Forest’—are to be found in her oeuvre.

FRIDA KAHLO

What I Saw in the Water, 1938 |Two Nudes in the Forest, 1939

Much of her work is concerned with her own physical pain (she was left permanently disabled by a horrific streetcar accident when she was eighteen) and by the emotional pain caused by the infidelities of her husband, mural painter Diego Rivera. Yet she certainly had passionate affairs with women, and among the facets of identity which she confronted in her work and in her life was her ‘butch’ side. She was often photographed wearing men’s clothing, and a famous painting, ‘Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair’, shows her in a man’s suit, surrounded by locks of hair, having shorn her head. The words of a popular song are painted above: ‘Mira que si te quise fue por tu pelo, ahora que estás pelona ya no te quiero’ (‘I loved you for your hair, now that you have cut your hair, I do not love you’).

Frida Kahlo, Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, 1940

A lesbian commentator might note that this painting follows on very Interestingly from the two lesbian images found in the paintings ‘What I Saw in the Water’ and ‘Two Nudes in the Forest’. Moreover, the Frida of this self-portrait is firmly placed on the canvas, upright on a sturdy chair, gazing at the viewer with what looks more like unapologetic defiance than grief. This is in marked contrast to many other self-portraits, which depict Kahlo as a baby, a wounded deer, a tearful and broken victim, the tiny wife of a larger-than-life Diego. Given that Frida developed such a direct and rich vocabulary with which to show her pain and vulnerability, I suggest that we trust the presentation of strength and solidity in ‘Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair’. This is a strong woman constructing self-reliance out of her refusal of femininity.

Frida Kahlo (center) with family

Two such contrasting painters, two such different sets of meaning for ‘lesbian’. Much remains to be gleaned from a lesbian study of de Lempicka and Kahlo: their positioning relative to the political struggles around them, the positioning of ‘lesbian’ in relation to those same struggles, their response to the ‘lesbian’ of their time and place, the meaning which their ‘lesbian’ images hold for lesbian spectator today, the significance of the lesbian relationships they both had. By such inquiry our understanding of the complex relationships among sexuality, sexual identity, politics, historical moment, class, culture, ethnicity, gender and art begin to develop a tighter focus, a stronger base. By refusing to make lesbian meanings we are restricted to a partial and politically static enterprise, forever seeing Kahlo in the shadow of Rivera, unable to comprehend de Lempicka’s self-conscious perversity.

Tamara de Lempicka, Spring, 1928

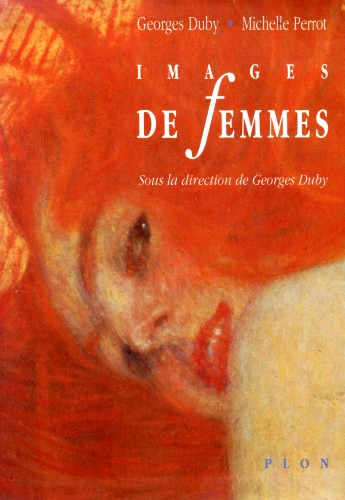

LESBIANS IN ART (II): A LADY HARWARDEN PHOTOGRAPH & LEMPICKA’S ‘DUCHESSE DE LA SALLE’

Lady Hawarden & Tamara de Lempicka

Anne Higonnet

From Georges Duby & Michelle Perrot, ed., Images de Femmes (Paris: Éditions Plon, 1992) p. 154. These excerpts translated by Richard Jonathan.

Homosexuality is a term introduced by psychoanalysis. But, if one can hardly speak of ‘lesbians’ before the twentieth century, one can evoke mutual attraction between women. Excluded from the professions and from masculine sociability, bourgeois women necessarily fell back on a life one can call ‘homosocial’. The outbursts of affection that marked their relations seemed perfectly acceptable, because covered by the code of sentimentality. At the same time, in the particular domain of the visual, access to image-making enabled women not only to express but also to amplify desire in images. The new technology of photography, in particular, did not require any professional training, which at the time was reserved for men. Thus, throughout the nineteenth century, one finds images such as that of Lady Clementina Hawarden, in which the tender gesture between two sisters becomes the physical equivalent of the reciprocal gaze between one of the sisters and the photographer, who is her mother.

VISCOUNTESS CLEMENTINA HAWARDEN (1822-1865)

Isabella Grace and Florence Elizabeth Maude (detail) | © Victoria & Albert Museum

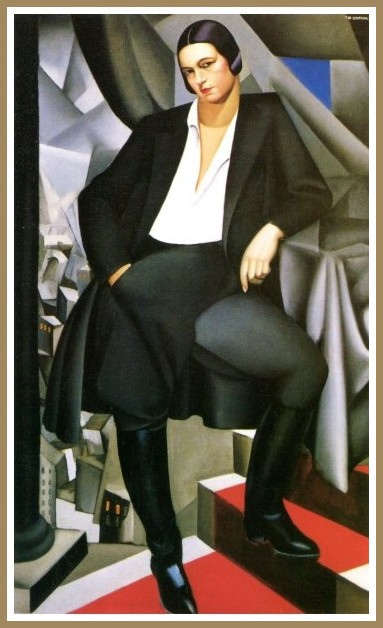

When, in the twentieth century, a woman would want to express her desire for other women, she would find more sexual but less ‘feminine’ means to do so. Tamara de Lempicka represents the Duchesse de la Salle in equestrian-style clothes, a lesbian recognition sign. The low-cut neckline, the nonchalance of the self-confident pose, the prominently exposed thigh—everything reinforces the image of an imperious sexuality. The virile character of this sexuality keeps it in the regime of the masculine, but the aspects of the portrait that promise an emancipation from the dominant models of representation are those which it shares with the Hawarden photograph: the exchange of direct gazes between women that structure our perception of the image, and the urban site of this exchange, a sign of the modern condition.

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA

Portrait de la Duchesse de la Salle, 1925

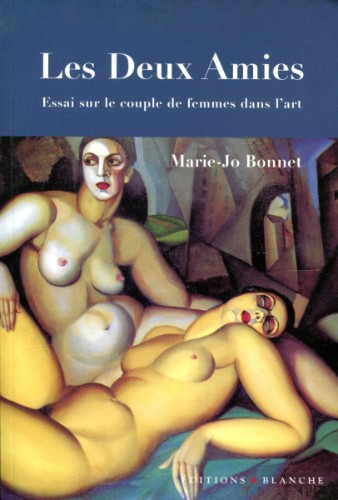

LESBIANS IN ART (III): TAMARA DE LEMPICKA

Tamara de Lempicka’s ‘Two Friends’

Marie-Jo Bonnet

From Marie-Jo Bonnet, Deux amies: Essai sur le couple de femmes dans l’Art. (Paris: Éditions Blanche, 2000) pp. 198-205. These excerpts translated by Richard Jonathan.

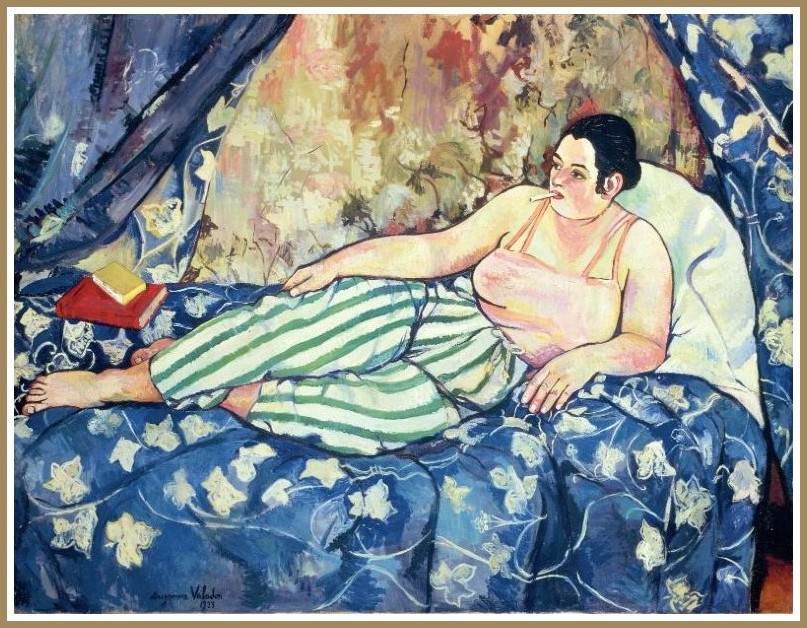

Among the European artists who found in their Paris exile a path to artistic fulfilment, Tamara de Lempicka is the very incarnation of audacity in seeking representation for women’s identity in society. Born into a wealthy family in Poland in 1898, she arrived in Paris in 1918 with her husband, Tadeusz Lempicki, who she had married in the midst of the revolutionary upheaval in Petrograd in 1916. Their daughter, Kizette, would be born in Paris during their first year there. Very quickly, however, the marriage would unravel. Tadeusz refused to work even though the couple had run out of money. It was in these difficult circumstances that Tamara decided to become an artist. She moved to Montparnasse, just next to Ira Ponte, with whom she would have an affair [see Portrait of Ira above], and registered at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière. She would also study at Maurice Denis’ studio, then at that of André Lhote. She travelled in Italy. In 1922 she persuaded Colette Weil to sell her first canvases in her gallery. That same year she participated in the Salon d’automne, where the following year she would show the Deux Amies [see Two Friends above]. Incidentally, Suzanne Valadon showed her admirable Chambre bleue at the same exhibition.

Suzanne Valadon, La Chambre bleue, 1923

That barely five years after her arrival in Paris Tamara de Lempicka would break a taboo by painting Two Friends is already noteworthy, but what constitutes a real turning point in the history of the representation of female couples is that this work, of imposing dimensions (130cm x 160cm), represents a scene of lovemaking and orgasm between two women in a ‘cubist’ city. Indeed, for the first time, the couple is shown in the City*, integrated into a modern civilized world, and not in a scene associated with the pleasures of the bedroom, or a harem, mythology or nature. And this is not the only domain in which it innovates. Behind the women rise modern buildings depicted in the cubist manner, curiously contrasting with the post-coital peace of the two powerfully ‘architectural’ bodies. The whole painting, in fact, is constructed on the contrast between the sharp angles and broken lines of the cubist city and the volumes and curves of the women’s bodies; contrast, or rather ‘put into perspective’, as the original title of the work, Perspective, would have it. Is the city broken because it still refuses to recognize love between women, thereby figuring a world made all the more chaotic by the almost immodest majesty of the lovers’ pacifying orgasm?

* ‘City’, capitalized, renders the French Cité, ‘community of citizens’. The author uses the word as a shorthand for ‘social institution’, meaning ‘that which is socially recognized’. Her book highlights the fact that while both heterosexual and male homosexual relations have, since Antiquity, been socially institutionalized and represented, lesbian relations have not.

Tamara de Lempicka, Andromeda, 1928

De Lempicka’s contemporaries did not see the importance of the city behind these female nudes. A certain Arsène Alexandre even described them as ‘perverse Ingrism’, thus ignoring both the modernity of the style and the novelty of the vision. The fact is that Tamara de Lempicka did not reserve this mise en perspective of the city for her nudes alone. It is to be found in other ‘homosexual’ paintings such as Portrait of Suzy Solidor and Portrait de la Duchesse de Salles, so carnal in her masculine outfit [see above for both paintings]. If Tamara de Lempicka loves women, if she is moved by their beauty, their curves, the overwhelming power of a feminine desire capable of transgressing conventions, she also knows, as an artist, that the City is not a harem. All her work proclaims this, with her highly personal way of tightly framing her subjects giving us the impression that they will break out of the frame as soon as they raise their head. In her paintings of the 1920s, the awareness of the place of women in the City is so innovative that her contemporaries had trouble detecting it, so obsessed were they with the erotic freedom of her female and male nudes.

Tamara de Lempicka, Women Bathing, 1929

In 1929, Arsène Alexandre would come to revise his judgement of Lempicka’s work: ‘An art so carefully conceived, so deliberately executed, so demanding of mental and manual resources as this one has no place for perversion.’ Then, making reference to Pascal’s famous aphorism, ‘man is neither angel nor beast, but he who would act the angel acts the beast’, he continued: ‘An artist as remarkable as this one finds in her energy and her faculty to generalize the meeting point, or the merger point, between beast and angel, and she leaves us to dreamily contemplate the forms and contours that we have at last come to appreciate’.

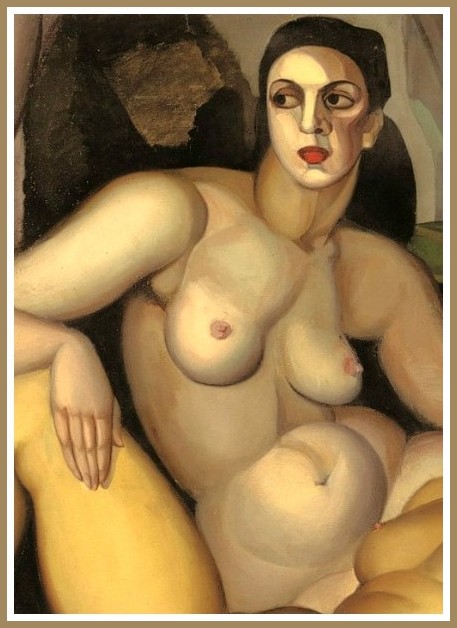

Tamara de Lempicka, Seated Nude, 1925

Indeed, she can leave in dreamy contemplation men who are used to seeing women model their desires themselves. Is it not surprising, however, that he compared her to Ingres when in fact her painting vocabulary draws primarily on that of André Lhote? In fact, Tamara de Lempicka, in Two Friends, ingeniously appropriates the language of modernity and neutralizes its impulse to destroy the image and beauty. In her painting, in contrast to the Cubist vision of the feminine nude, the bodies are not broken up into pieces but are whole. In continuity with the classical tradition of form and contour, they constitute a paradoxical ‘hymn to beauty’ that the painter Magdeleine Dayot perceptively noted when she wrote: ‘Tamara de Lempicka’s bodies are fresh and alive, constantly alert to rhythm; she respects the purity of line and conceives the nude as a hymn to beauty rather than as a pitiful presentation of human degeneration, as certain painters today too often depict it’.

Tamara de Lempicka, Reclining Nude, 1925

In contrasting the lovers’ orgasm with the broken city, was Tamara de Lempicka making propaganda? Propaganda in favour of the modern woman who drives her own sports car [see Tamara in the Green Bugatti above], wears trousers, goes skiing, kisses her lover’s thick red lips, or assumes her erotic power as she stares the viewer down. If the number and variety of her nudes testifies to an almost militant desire to assert a free feminine Eros, her way of architecturally structuring bodies in space, of pushing against constraining frames, of inscribing emotion in flesh, of audaciously painting La Belle Rafaela [see above] or Myrto, all derive from the same Amazonian strategy: to inscribe women in modernity while neutralizing the nihilist tendencies of the art of her time. Neither languorous odalisque nor Cubist assemblage, the modern woman is embodied fully in the City, where she proudly affirms her right to paint as she pleases.

Tamara de Lempicka, Myrto, 1929 [colorized from b&w]

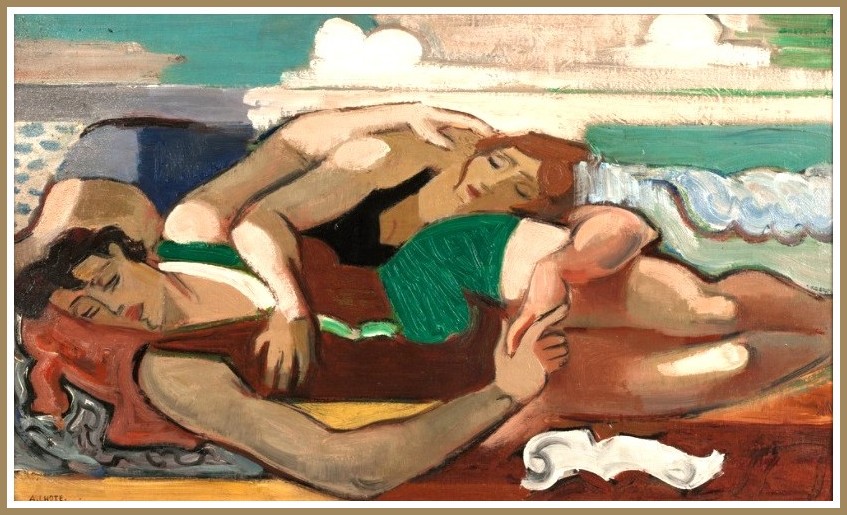

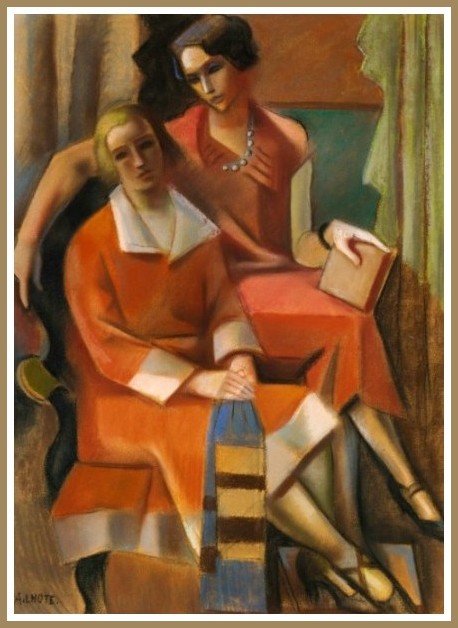

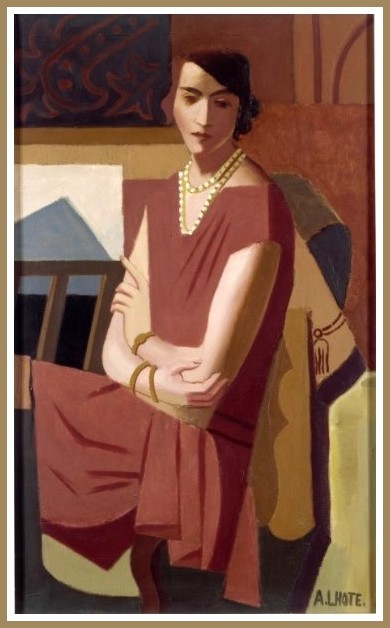

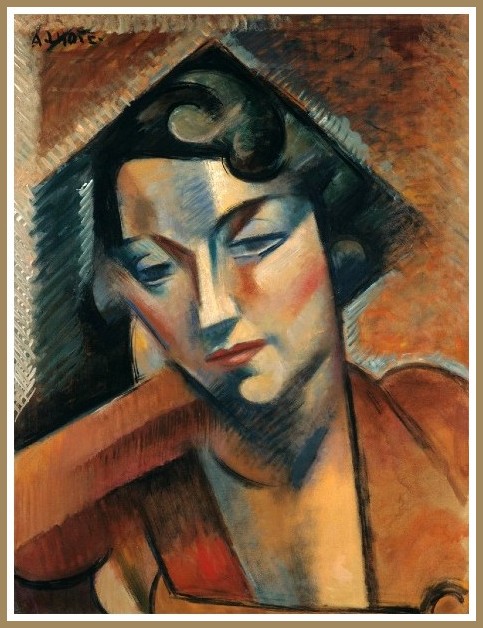

That Tamara de Lempicka drew from André Lhote’s teaching the elements of an inimitable neo-Cubist style is recognized today, but that she found in his painting a legitimation of her own politico-erotic audacity has not yet attracted the attention of art historians. The fact is, at least two of André Lhote’s works must have struck the young Lempicka: Les Dormeuses, a pencil drawing from 1921 that was frequently reproduced in contemporary periodicals…

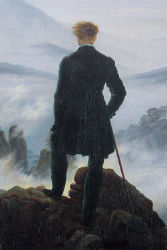

André Lhote, Les Dormeuses, 1921

… and La Plage (Les Baigneuses), a painting Lempicka must have seen since it was exhibited, along with one of her own works, at the same Salon d’automne.

André Lhote, La Plage (Les Baigneuses), 1928

La Plage (Les Baigneuses) depicts two women lying head-to-foot on a beach, enlaced in an embrace, the head of one resting on the thigh of the other who, in turn, is resting her head on the other’s hip. Their eyes closed in sleep, they hold hands tenderly. Tamara de Lempicka chose the same arrangement of bodies for Two Friends, changing only their orientation. The head of the woman in the foreground is on the right and no longer on the left, and the position of the woman in the mid-ground has changed. She is sitting up, her forearm resting on the knee of her lover whose eyes are closed, not in the relaxation of sleep but in the bliss of pleasure [see Two Friends above].

Tamara de Lempicka, Sleeping Woman, 1935 & 1930

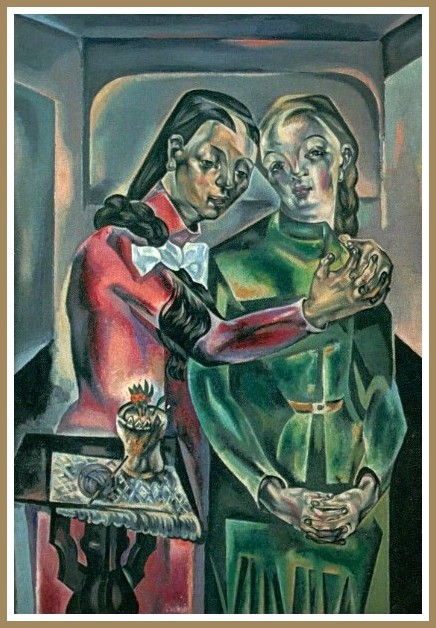

André Lhote took great interest in female ‘friendships’, whether from his viewpoint as an artist (his work includes several versions of this theme) or—what is much less well known—from a perspective that touches on his own inner circle. Indeed, his first wife, Marguerite, probably had a relationship with Anne Fonjallas, a young woman he met at Avignon before the war and who he would paint with her sister in his 14 juillet en Avignon.

André Lhote, 14 juillet en Avignon, 1930

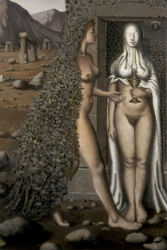

In 1925, Lhote painted Marguerite and Anne and titled the work Les Deux Amies. The women seem very close. The pose suggests intimacy, since Marguerite sits on the arm of the chair in which Anne is seated, her arm on the back of the chair enveloping Anne, while her gaze conveys a tender attention. Is it a look of love? André Lhote, in his commentary on the painting, offers no insight, since he is divided between a creative drive that strives for ‘the painterly use of passion’ and a depersonalization of the subject proper to modern art.

André Lhote, Les Deux Amies, 1925

No matter that he said, ‘one must lack confidence in one’s technique if one is afraid of one’s subject’, the fact is this particular subject is constantly avoided. It is ignored by the critics, who focus only on the Cubist technique (as if technical innovation were more subversive than the subject it serves), and it is passed over in silence by the artist himself, who gets so carried away by his discourse on technique that the subject of the painting does not even get a mention. Thus one reads, in a commentary on La Plage (Les Baigneuses) [see above] written twenty years after the completion of the painting, this surprising refusal to mention the female couple: ‘A consistent rhythm should draw in the elements of the composition. Here, it is the horizontal rhythm, that of the invisible beach and the sea we suppose is there. Around the center of the canvas, the arms join together like a buckled belt. It is immensely pleasurable to combine purely painterly elements with those, more accidental, that derive from natural phenomena (shadows, reflections, etc.).’

André Lhote, Femme Assise, 1925

To speak of the ‘invisible beach’ and the ‘sea we suppose is there’ for a picture plane that is almost entirely occupied by two interlaced women is simply to elude the visible and disown the eye. If it is understandable that André Lhote indulges in technical description as a way of maintaining a ‘respectful distance’ from his two ‘Amies’, it is less acceptable that his subversion of the subject has elicited no critical comment. Why speak of technique when it is clear that he has allowed himself, like few other painters have done, to be moved by the turpitude of love?

André Lhote, Femme accoudée (Portrait d’Anne F.), 1928

This question brings us to the heart of the matter, namely that the unveiling of female homosexuality in art has long confused the imaginary woman and the real one. Lhote believed that woman is the metaphor of Western painting, as is clear from his remarks of 1958 on Maria Blanchard’s Les Deux Amies, where he implicitly refers to gender identities to explain the public’s antipathy toward her painting. He writes: ‘In a shimmering framework that is but a simple accompaniment, two young women solemnly stand awaiting, since their birth by the hand of a damned painter, to be recognized by the major critics. None of them have written a word. The reason for this silence is easy to guess. Lipchitz liked this very unfeminine painting. To no avail, because today femininity is precisely what one values most in the work of male painters. As long as careless painting is fashionable, there will be no place for carefully composed masterpieces.’

Maria Blanchard, Les Deux Amies, 1921

When we see how André Lhote dissociates subject and form, we see how modernity appropriates a symbolic field for the exclusive use of men, since no symbolization of love between women is possible without a relation between subject and form, signified and signifier.

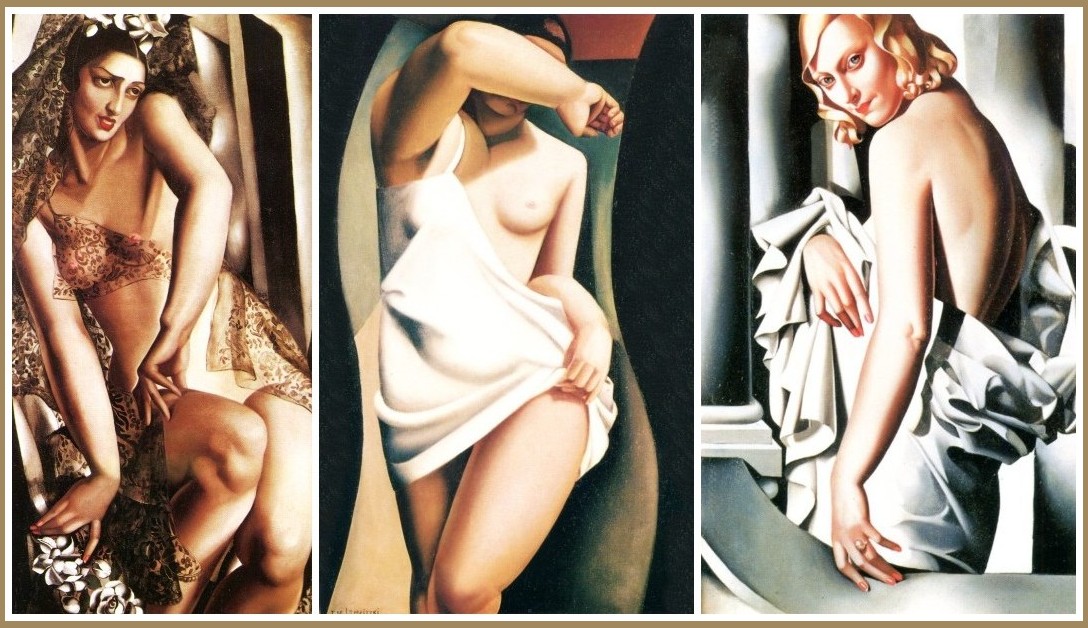

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA

Portrait of Nana de Herrera, 1929 | The Model, 1925 | Portrait of Marjorie Ferry, 1932

LESBIANS IN ART: BOOK REFERENCES

TAMSIN WILTON

Lesbian Studies

MARIE-JO BONNET

Les Deux Amies

GEORGES DUBY

Images de Femmes

TAMARA DE LEMPICKA’S FAVOURITE PAINTERS

Laura Claridge

Tamara de Lempicka painted in iconoclastic, dramatically modern styles, while she also pledged allegiance, in color and in brushstroke, to Pontormo…

Pontormo, Venus and Cupid, c.1532-34

Giovanni Bellini…

Giovanni Bellini, Madonna and Child, c.1480

Caravaggio…

Caravaggio, Saint John the Baptist, 1602-03

and Antonello da Messina.

Antonello da Messina, The Virgin Annunciate, c.1477