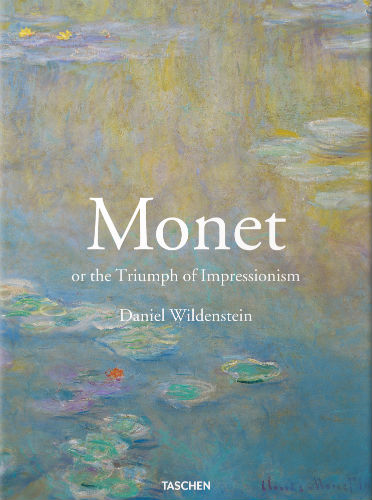

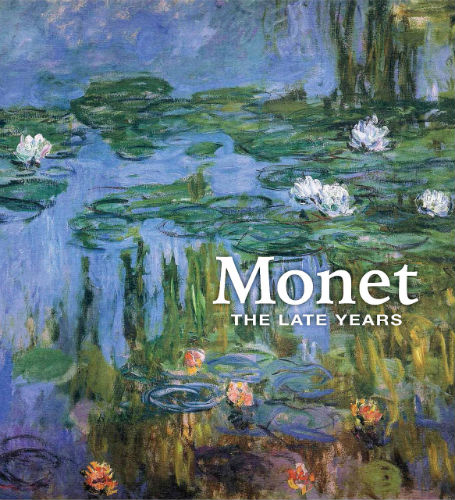

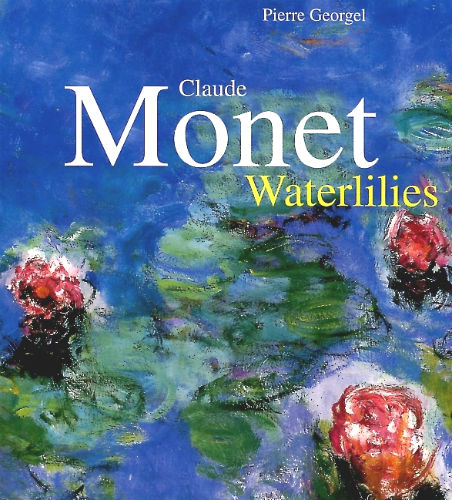

Monet & Dali: Claude Monet, Water Lilies

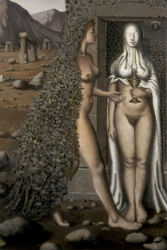

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Three Chapter 4

Salty diction, tender disillusion, beyond the rules of discord and resolution, the beguiling movement of a melodic line: Over a shimmering bed of flute and soprano, Julius Hemphill’s alto sax teaches dignity in loneliness.

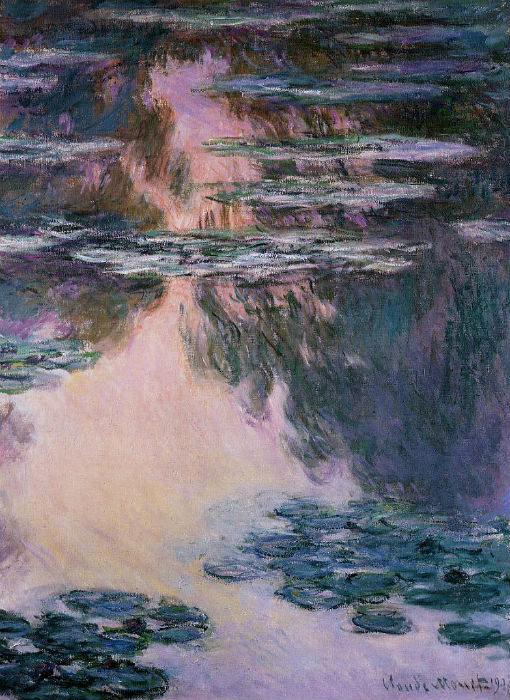

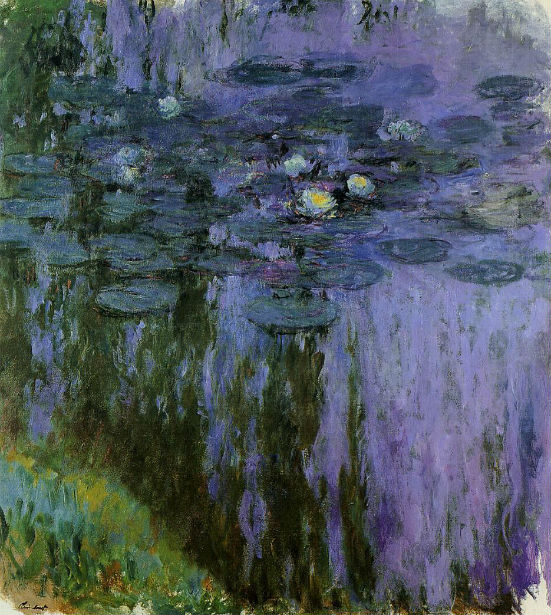

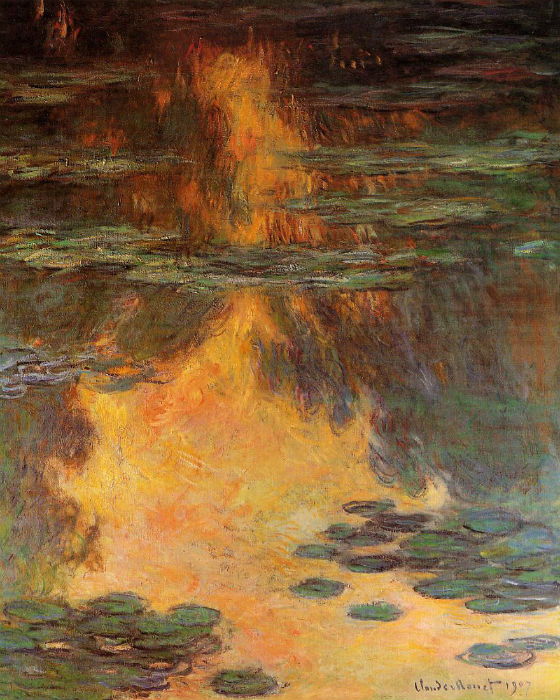

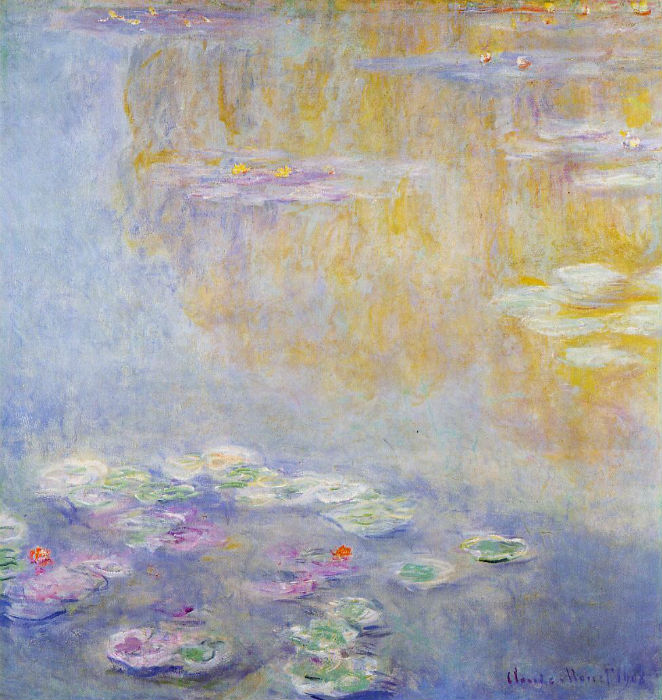

Claude Monet, Water-Lilies, 1907

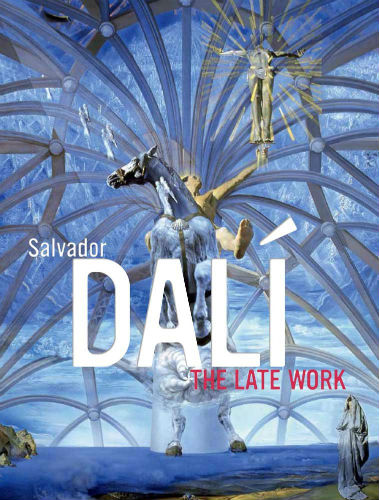

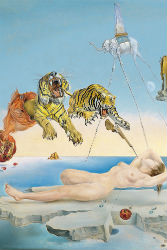

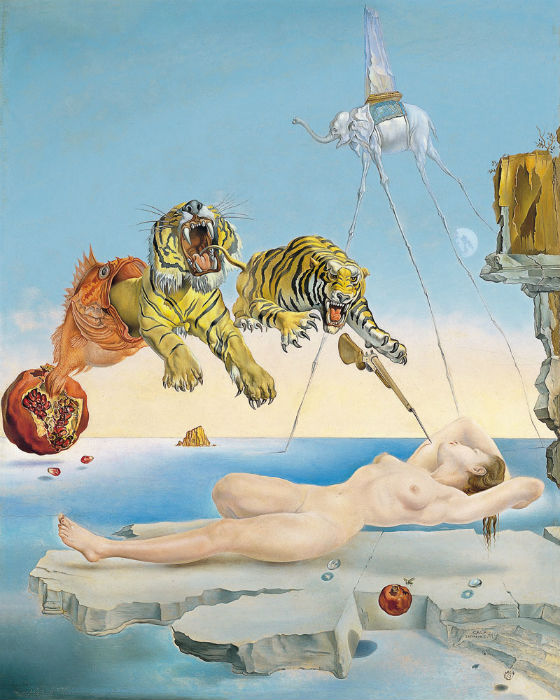

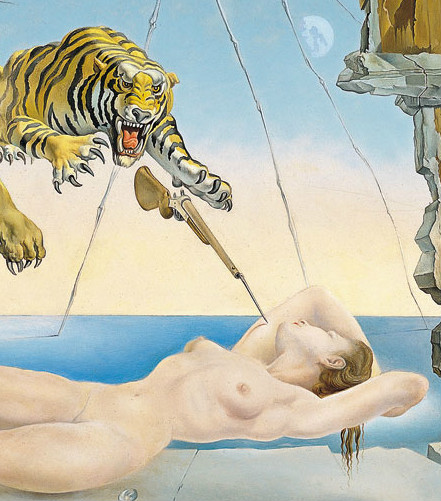

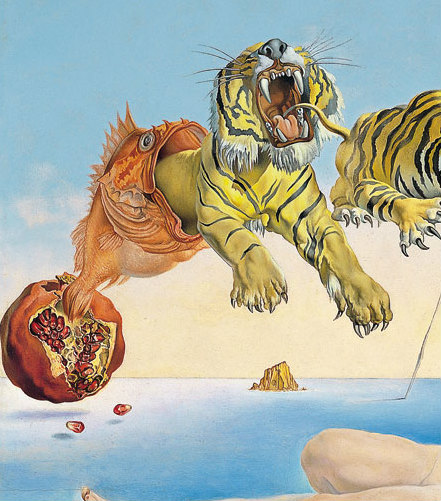

Salvador Dali, 1944

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Awakening

̶ When a man comes inside you, you feel it; you feel the beating of his heart in the pit of your belly, you feel the tremor of his spasms in your bones.

Gazing out across the Seine into the glittering night, we take in the moving gestures of the music. Tongues of fire play on black water, horns and woodwinds sparkle.

̶ It’s like a Dali painting, a man’s orgasm. A woman’s is more like Monet.

̶ Which Monet?

̶ The Nymphéas, of course!

̶ Of course. All 250 of them?

̶ Yes, when you’re lucky enough to have a marathon of good love-making.

PIERRE GEORGEL ON MONET’S WATER LILIES

A selection of excerpts from Pierre Georgel, Claude Monet: Water Lilies (Paris: Hazan, 1999) | Pierre Georgel was Director of the Orangerie Museum (Paris) between 1993 and 2007.

At the age of fifty-three, Monet, the pioneer of Impressionism, already had a vast oeuvre behind him. His work had evolved. The aesthetic of the instant and captured transient sensation, of which he had shown himself a master, no longer satisfied him. ‘Instantaneity, facile things done at a stroke disgust me,’ he admitted. Landscape, the very genre which he, more than any other artist, had rejuvenated, with its standard formats, rules of composition and obligatory horizon and vanishing point, had begun to reveal to him its limits. He now aspired to profoundly reinvent landscape, to discover its essence through both direct contact with the elements and a more global vision less dependent on the contingencies of time and place. He sought to embrace not only the visual appearance of things, light’s ever-changing metamorphosis of form and color, but also its all-pervasive, penetrating action, the feeling of communion it produces within us.

Claude Monet, Wisteria, c.1925

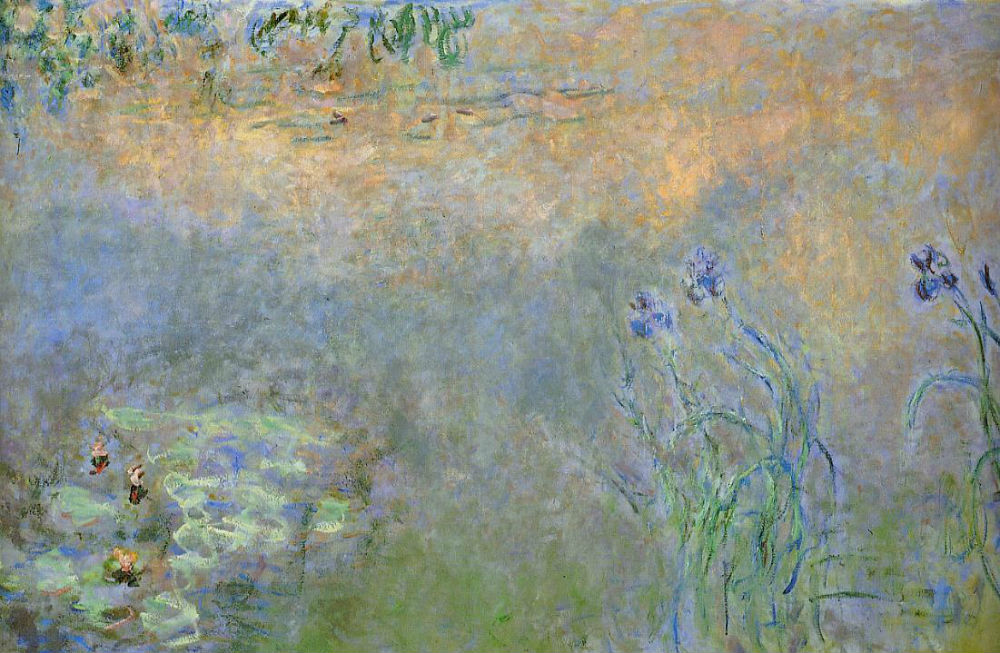

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond with Irises, 1920-26 (right half)

Monet was striving for a more synthetic organization, a heightened sense of spatio-temporal continuity, and a feeling of closeness or, better still, intimacy between landscape and spectator.

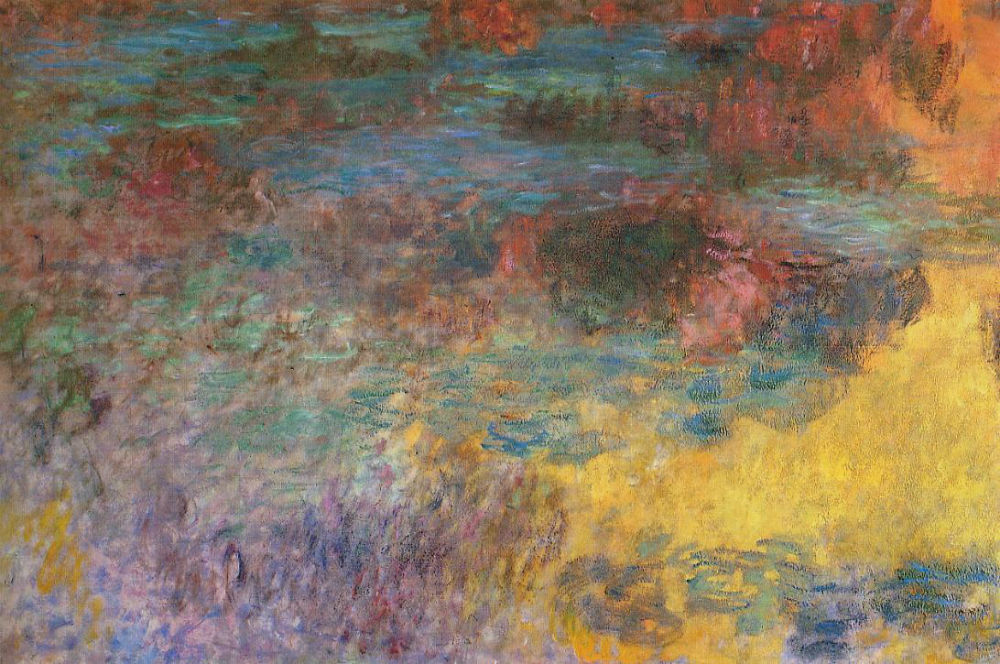

The garden was a résumé of the properties and elements in nature whose expression he had prioritized: uncertainty, contingency and fluidity. In a painstaking process of pruning and rearrangement, water, sky, reflections of clouds, the chaos of plant life—everything that eluded static form and intensified the action of light—was discreetly stage-directed. He cultivated fluid effects and the sensation of immersion they engender, juxtaposing water, reflections, swaying lily clusters, overhanging branches laden with silky or sequined foliage and the sinuous contours of the pond and the path around it to produce subtle gradations of color.

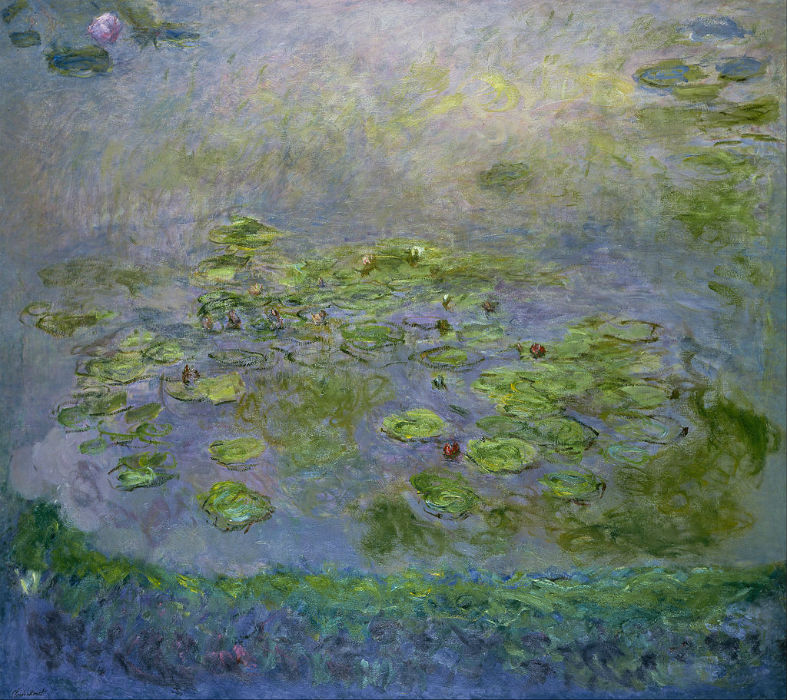

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1916-19

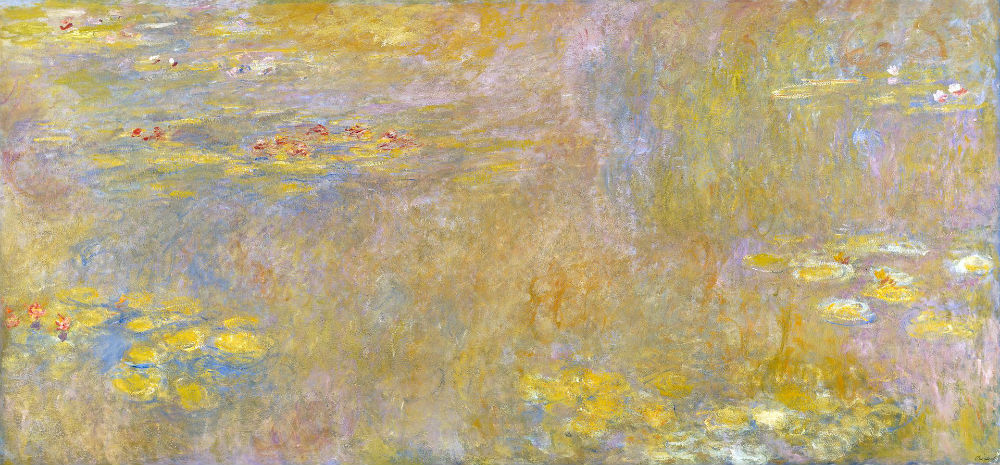

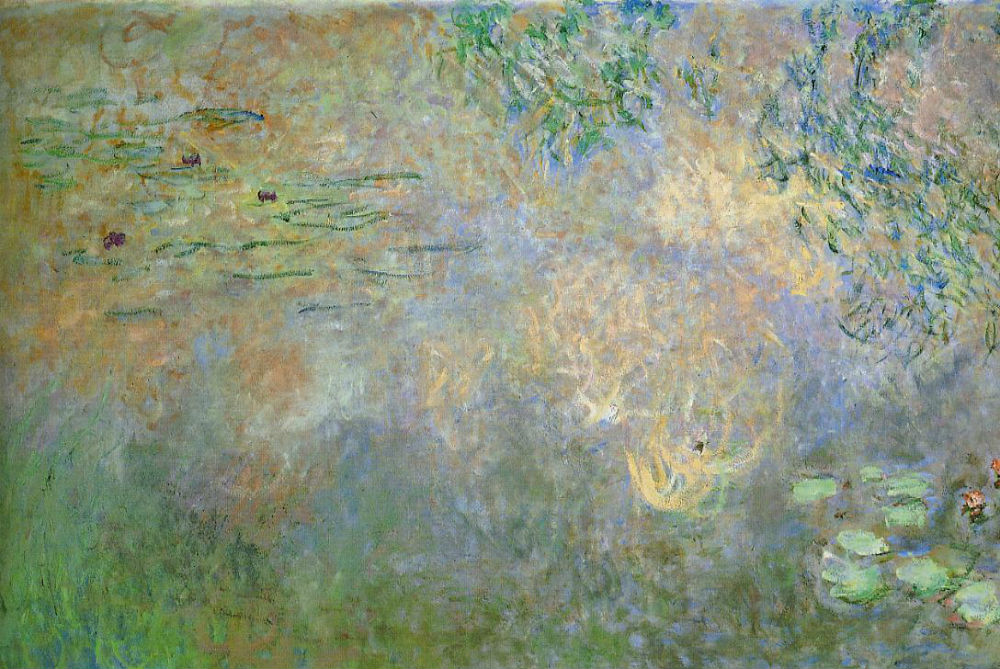

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, after 1916

Rather than just being the last of the great series—the milestones of Monet’s oeuvre—the Water Lilies series was their outcome and final transcendence. Here was a radicalization of an evolution in which the picture’s center of interest had been gradually shifted from the subject, however evocative, to the representation of luminous phenomena, the mechanical act of seeing, and more generally, the perception of reality. The garden is treated less as a subject in itself—which it also intrinsically is—and more as the quintessence of all landscape subjects and of the conditions governing them. The painter’s final, supreme effort consisted of capturing ever more impalpable and fugitive perceptions of reality.

Monet, within the context of the generalized goal of ‘synthesis’ which permeated fin de siècle art, goes further than his contemporaries in the unified treatment of space and the conception of each element as part of a total harmony. He does this not only in his conception of a continuous décor, which ‘envelopes the walls in its unity,’ but also in his choice of subject itself, water, the unified milieu par excellence, and in his representation of it as uninterrupted flow. Nature’s continuum is to become one with the continuum of the picture plane, which in turn fuses with the spectator whose thoughts, set adrift in formless matter, give way to dreams. Even our bodies themselves will become permeated by this phenomenon of subconscious impregnation.

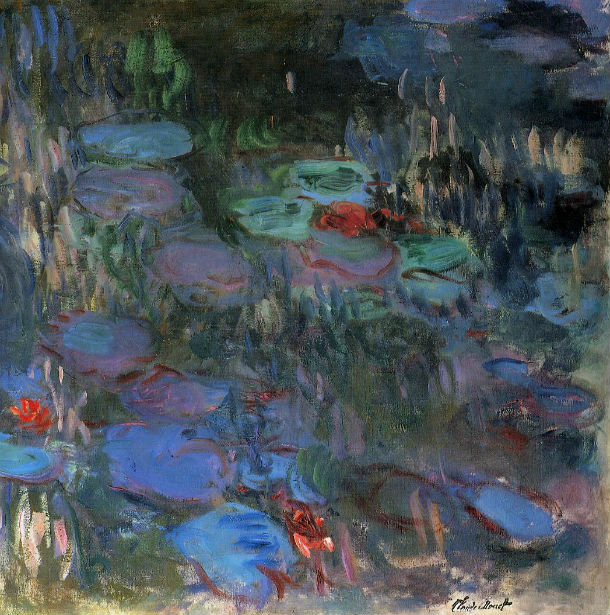

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1908

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1914-17

One is at nature’s elemental heart, dormant waters and mysterious plant growth are two different forms of one primordial reality, two modalities of the same innermost experience, each with its own associations and affective states. On one hand, one is drifting in boundless space, drawn perhaps towards death or regressing into the mystery of infancy. On the other hand, we are filled with a sense of suffocation, of torpor rather than peace.

The dialectic of whole and fragment was a familiar one to Monet, who liked to suggest, through seemingly arbitrarily framed close-ups, the vastness of the space extending beyond. It is here that the microcosmic character of the water garden intervenes, reflected and intensified by its different representations. The water landscapes are concentrated representations of a landscape, which is in itself a concentrated image of the universe. They are scale models of a totality reduced to its essential elements. Far from obstructing our consciousness of the continuum, fragmentation becomes simply another means of creating it.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1920-26

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond with Clouds, 1903

For Monet, a contemporary of Bergson and Proust, water, with its shifting surface, was the face of nature itself, described by its own elemental properties of contingency and fluidity. The spectator, dispossessed of his powers of control by his extraordinarily close point of view, is projected into an environment with no logical boundaries and containing no solid bodies other than leaves and flowers. Once all referential bases have been eliminated, the spectacle becomes almost immaterial. The only picture dated 1903 that one can be sure was not reworked at a later date is still very descriptive, with certain details rendered almost photographically. In the less detailed paintings from 1904, the paint is applied thickly, in brushstrokes that vary according to whether they are describing reflections, vegetation, or the water lilies. From then on, the image becomes increasingly synthetic and the execution more fluid—in the words of the critic Louis Gillet, ‘skimming the canvas’.

After 1906, the multiple layers of paint and the reworkings of the early years have almost disappeared. ‘The painting,’ wrote Gillet, ‘is now merely an essence, a sigh’.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies : Clear Morning with Willows, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais-Musée de l’Orangerie / Michel Urtado

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: The Two Willows, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais-Musée de l’Orangerie / Michel Urtado

Simultaneously, the composition itself seems to dissolve. Floating marks, mere suggestions of forms, with here and there the more precise volumes of the water lily flowers, combine with vaguely-defined areas of reflections of patches of sky, clouds, and the indistinct masses of trees.

There is no distinguishable center of interest or hierarchy.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies : The Clouds, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais-Musée de l’Orangerie / Michel Urtado

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Morning, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais-Musée de l’Orangerie / Michel Urtado

‘The painter,’ wrote another critic, Roger Marx, ‘has deliberately disengaged himself from western tradition. No more pyramidal compositions and lines to channel our attention: fixity and immutability, seem to contradict the very principal of fluidity for him. He seeks a diffuse, all-over attentiveness.’

All that remained of the geometrical model, which had governed our representation of reality since the Renaissance, was a fluid grid comprised of vertical tree reflections and horizontal water lily islands. We no longer have a framework imposed on nature from the outside, but a permanent equilibrium that incorporates nature’s inconstancy.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Trees Reflections, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais-Musée de l’Orangerie / Michel Urtado

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1907

In certain respects, Monet only pushed to its climax his long-term (and by no means solitary) offensive against four centuries of rationalism in painting. However, the water landscapes add an entirely new dimension to the methods experimented with previously, one which completes the disintegration of traditional pictorial space. Nevertheless, the pretext was ‘realist’: it was the representation of heterogeneous optical phenomena produced by the coexistence on the same plane of real objects (water lilies) and reflections (of sky, clouds, and trees). On the one hand, the water lilies dotted around the pond break up its reflective surface. On the other, since we are looking down on the pond and the ‘real’ trees are on the opposite bank, we see the reflected landscape upside down, with the sky below us. The water lilies decrease in size towards a single vanishing point, while the reflections obey another, inverse perspective. ‘What could be more natural?’ one might ask. However, it is Monet’s framing of this banal spectacle, his inclusion of only the water-mirror and exclusion of what is reflected in it, that produces a kaleidoscopic patchwork of colliding fragments of reality. For those who came to it unprepared—even a connoisseur such as Roger Marx spoke of ‘disoriented surprise’—Monet’s spatial juxtaposition was as disconcerting as the one the future Cubists were then beginning to imagine. The most daring of the water landscapes, the vertiginously vertical canvases of 1907, were painted the same year as the Demoiselles d’Avignon.

The public was in fact receptive to the powerful disorientating effect of these strange micro-landscapes. Some reviews of the 1909 exhibition describe the state of confusion and dreaminess they instilled. The majority, however, dwelt on their poetic dimension, quoting Verlaine, Maeterlinck, and Debussy. A generation steeped in Symbolist reverie delighted in this art of allusion and illusion in which, in Roger Marx’s words, ‘certainty becomes conjecture’ and ‘enigma and mystery opens up a world of illusion and the infiniteness of dreams’.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1908

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond with Irises, 1920-26 (left half)

Monet was the first to insist on the objectivity of the water landscapes. ‘My intentions are not fanciful at all,’ he declared to Roger Marx. ‘These canvases are merely the result of a collaboration between solitude and silence, of a keen, undivided attention akin to hypnosis.’ But is this form of observation really so far-removed from what others termed imagination or poetry?

The majority of the new canvases were between one and two meters high, including many two meters square, and are executed in an almost brutally cursive manner. Light areas of cloud and flowers stand out on a dark ground applied with broad brushstrokes establishing the dominant chromatic tone. In the most worked canvases, a clump of vegetation or the contours of water lily leaves are highlighted by a shorthand calligraphy of scribbles, streaks, and flourishes rather than by line, strictly speaking. All of Monet’s refound energy manifests itself in this vehement body language.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies: Reflections of Weeping Willows, 1919-19

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond: Evening (left panel), 1920-26

In a rare commentary on the work of this period, published after his death by the journalist Thiébault-Sisson, Monet spoke of his technique’s mutation around 1914, but maintained that this was directly due to his cataracts. Altering his sensitivity to nuance, they had caused him to seek overall effects. He began treating form broadly ‘in masses,’ using ‘bright tones isolated in areas of dark tones.’ This explanation, too reductive, does nonetheless highlight a central feature of the period to come: Monet’s retreat from face-to-face confrontation with reality. No matter what role his eye problems played in this process, which had in fact started much earlier, they manifested themselves as much in the increased autonomy of formal values—which, without freeing themselves from their mimetic function, assert themselves with unprecedented authority—as by the greater scope left to the imagination. True, Monet continued painting from nature, but in a resolutely synthetic manner, in which memory and dream consolidate direct observation or take up where it leaves off.

Monet’s mural ensemble, now in the Musée de l’Orangerie, was both the subject’s faithful representation and its free transposition—a poetic synthesis of a place and of the notion of place. It was both the summing up and outcome of a lifetime’s work and was to the pond at Giverny what, for example, Les Contemplations and In Search of Lost Time were to Hugo and Proust respectively. Monet had only to find the appropriate form, and here his cataracts worked wonders.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies : Green Reflections, 1915-26

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) / Michel Urtado

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Setting Sun, 1915-1926

© RMN-Grand Palais (musée de l’Orangerie) / Michel Urtado

They forced him to synthesize the subject, first of all in ‘a series of overall impressions’—a formula perfectly adapted to large studies from nature—then in the mural ensemble itself. If one accepts that here his cataracts also only accentuated a more general process, one will note his emphasis on the ‘other-worldly’ dimension of the pond’s reality, as well as his detachment from direct observation.

Monet had sought to express the totality of nature and the fullness of experience through an all-embracing, synthetic means, which would be their perfect analogy. He succeeded in this, not by sacrificing any of his realist precepts, but by mobilizing the power of dream. From a wealth of real-life observation, he built a ‘pantheist poem’ in which everything both expressed and brought about the communion of man and universe.

Pierre Georgel, Claude Monet: Waterlilies

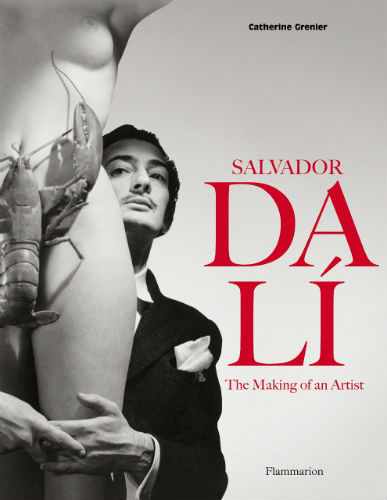

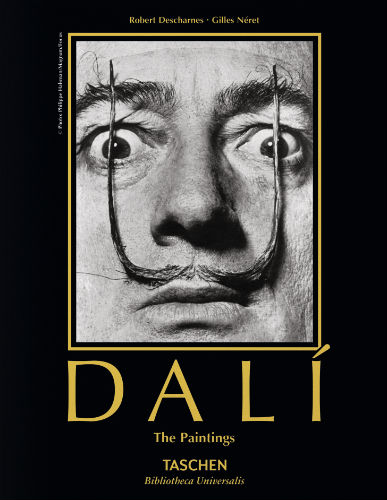

Monet & Dali: Salvador Dali, Dream-Bee-Pomegranate

ERIC SHANES ON ‘DREAM-BEE-POMEGRANATE’

From Eric Shanes, Salvador Dali (New York: Parkstone International, 2011), p. 152

Dali appropriated the tigers he included here from a circus poster. Indeed, the entire image has the look and visual immediacy of a poster, which perhaps accounts for its popularity. But ultimately this picture is ‘Surrealism made easy’. That is because the dream-events it depicts take place around someone sleeping. We therefore tend to interpret them as occurring in that person’s mind—as the manifestation of her dream—rather than as the projection of a dream per se that we need to fathom wholly in terms of our own non-rational experience.

Salvador Dali, 1944 (detail)

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Awakening

Salvador Dali, 1944 (detail)

Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second before Awakening

Moreover, both title and imagery enjoy a sense of connection and sequence. Thus in the foreground are the bee and pomegranate, while a further pomegranate bursts on the left, disgorging fish, tigers, and a rifle whose bayonet is about to prod the prostrate form of Gala awake in just one millisecond from now. Such connections and the sequence they follow are rational processes that make the proceedings very approachable conceptually. We are now a long distance away from ‘the depths of the subconscious’ because it is so easy to understand things in rational terms. By the mid-1940s Dali’s Surrealism was becoming a little too pat and predictable. Although there are undoubtedly memorable images here—the elephant with extended legs is a superbly imaginative conceit—nonetheless there are not enough such fancies to push the work into that ineffable imaginative dimension that lies beyond mere illustration.

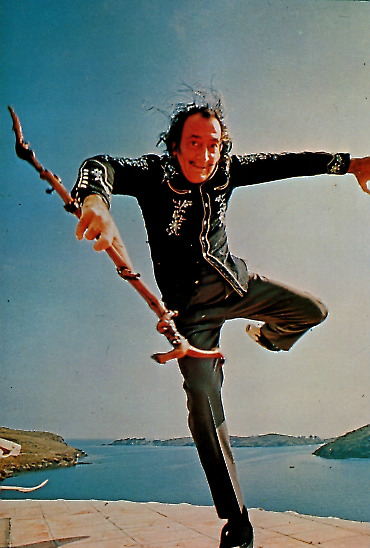

RÉGINE SCELLES ON SALVADOR DALI

From Régine Scelles, « Confrontation à la mort d’un frère et construction psychique », Le Carnet PSY 2010/6 (n° 146), p. 34-43. This passage translated by Richard Jonathan.

Salvador Dali had a brother who, of fragile health, died young, before Salvador’s birth. During a TV show Dali, with his customary mastery of theatrics and derision, said: “They always spoke of me in relation to my dead brother: ‘He must wear a scarf because his brother caught a cold in such circumstances’. So I wasn’t myself, I was the dead brother.” He continued: “Thanks to this constant game of killing by my eccentricities the memory of my dead brother, I succeeded in fulfilling the sublime myth of the Dioscuri, Castor and Pollux: one brother dead and the other immortal”.

Salavador Dali | Photo: Robert Whitaker

Salvador Dali

Unable to interact in reality with his brother, Dali established a link with the brother who existed in the parent’s mind. All his life, he said, suffering sublimely, he had tried to refrain from obliterating, from killing his brother by incarnating him. Destined by the adults to revive this fragile, beloved double, he devoted all his psychic energy to actively refusing this mission. Thus, in his own way, he tried to save his dead brother by refusing to exist in his place, by becoming something other than what his parents had decided for him.

See also: VINCENT VAN GOGH IN THE EYES OF HAROLD P. BLUM: Fantasies of Replacement: Being a Double and a Twin.