PART 2: III. LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG: FOUR SONG COMPARISONS | IV. CONCLUSION

An Experiment in Comparison

LEONARD COHEN & SERGE GAINSBOURG – PART 2

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

THIS IS PART 2 OF THE ESSAY. TO READ PART 1, CLICK OR TAP THE IMAGE BELOW.

3. TAKE THIS LONGING | L’EAU À LA BOUCHE

TAKE THIS LONGING

Leonard Cohen

Many men have loved the bells

You fastened to the rain

And everyone who wanted you

They found what they will always want again

Your beauty lost to you yourself

Just as it was lost to them

Take this longing from my tongue

Whatever useless things these hands have done

Let me see your beauty broken down

Like you would do for one you love

Your body like a searchlight

My poverty revealed

I would like to try your charity

Until you cry, ‘Now you must try my greed’

And everything depends upon

How near you sleep to me

Just take this longing from my tongue

All the lonely things my hands have done

Let me see your beauty broken down

Like you would do for one your love

Hungry as an archway

Through which the troops have passed

I stand in ruins behind you

With your winter clothes, your broken sandal strap

I love to see you naked over there

Especially from the back

Oh, take this longing from my tongue

All the useless things my hands have done

Untie for me your hired blue gown

Like you would do for one that you love

You’re faithful to the better man

I’m afraid that he left

So let me judge your love affair

In this very room where I have sentenced mine to death

I’ll even wear these old laurel leaves

That he’s shaken from his head

Just take this longing from my tongue

All the useless things my hands have done

Let me see your beauty broken down

Like you would do for one you love

L’EAU À LA BOUCHE

Serge Gainsbourg

Écoute ma voix, écoute ma prière

Écoute mon cœur qui bat, laisse-toi faire

Je t’en prie ne sois pas farouche

Quand me vient l’eau à la bouche

Je te veux confiante, je te sens captive

Je te veux docile, je te sens craintive

Je t’en prie, ne sois pas farouche

Quand me vient l’eau à la bouche

Laisse-toi au gré du courant

Porter dans le lit du torrent

Et dans le mien

Si tu veux bien

Quittons la rive

Partons à la dérive

Je te prendrais doucement et sans contrainte

De quoi as-tu peur, allons, n’aie nulle crainte

Je t’en prie, ne sois pas farouche

Quand me vient l’eau à la bouche

Cette nuit près de moi tu viendras t’étendre

Oui je serai calme, je saurai t’attendre

Et pour que tu ne t’effarouches

Vois, je ne prends que ta bouche

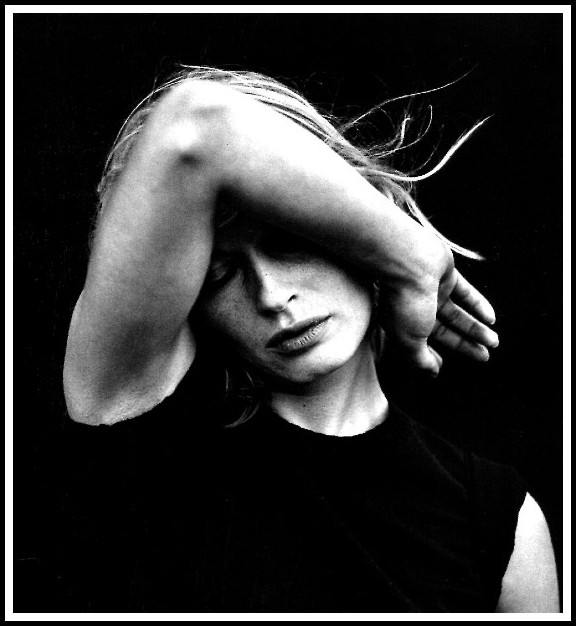

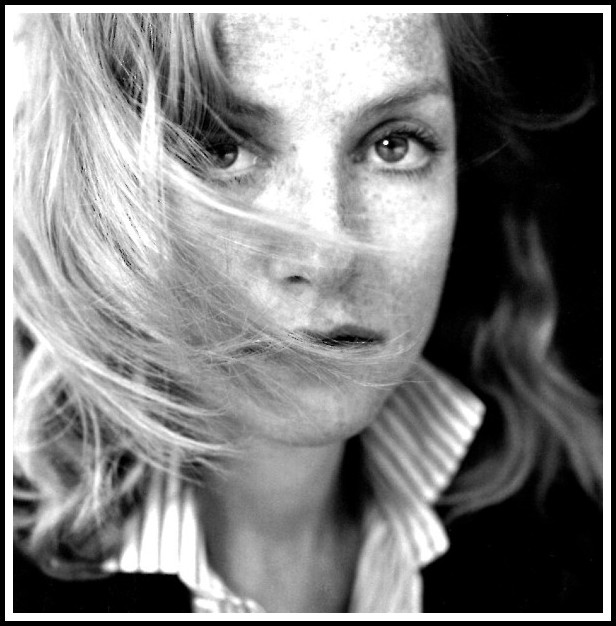

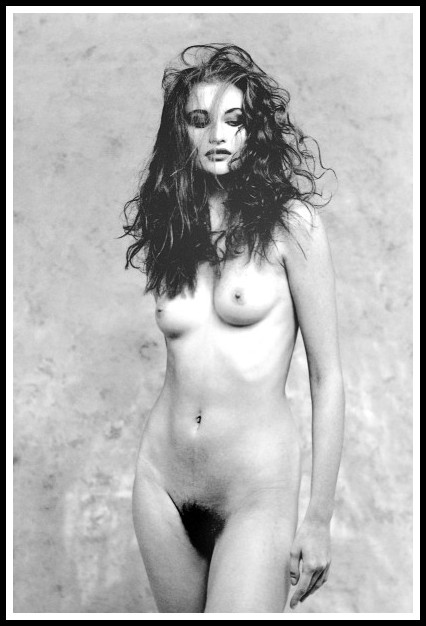

Peter Lindbergh, Annie Morton, 2000

‘Take this Longing’ and ‘L’Eau à la bouche’ are both songs of frustrated desire, but in very different registers. Serge’s song has the light-hearted ease befitting the film for which it was written. It is very much a song in which the ego is master in its own house: the man is not alienated in his desire, the woman is not neurotic in her resistance; each knows their role in a familiar game. There is no doubt that the man, in the end, will get the woman into his bed; there is no doubt that the satisfaction he seeks will be a simple pleasure, like a warm coat in winter or a hearty meal with good wine. Exquisitely wrought, both musically and lyrically, the song is transparent. It makes no demands on the listener, it revels in its status as ‘art mineur’. Art tout court, however, is never transparent: something in it always escapes capture. Indeed, despite the utter charm of the song, it cannot engage us ‘in that place we cannot master’, that place where the ego is not master in its own house: that place where art takes place. Leonard’s song, in contrast, is situated entirely in that place. There, desire alienates; sex, no longer a mirror game, becomes erotic, an encounter with alterity. The self is not secure, the other is not obvious, and the more intimate the man and woman become with this unfamiliarity, the more occasion they have to ‘become who they are’. Walk on by if you want a warm coat and a hearty meal: here, sex is a trip into transgression. Now, if ‘Take this Longing’ is such an excellent song, it is largely because its metaphors are at once highly enigmatic and highly suggestive, and because the longing it speaks of throws one, as it does the singer, back upon oneself. Being spurned forces one to interrogate one’s desire, and that experience holds out the possibility, like the searchlight in Leonard’s song, of some revelation.

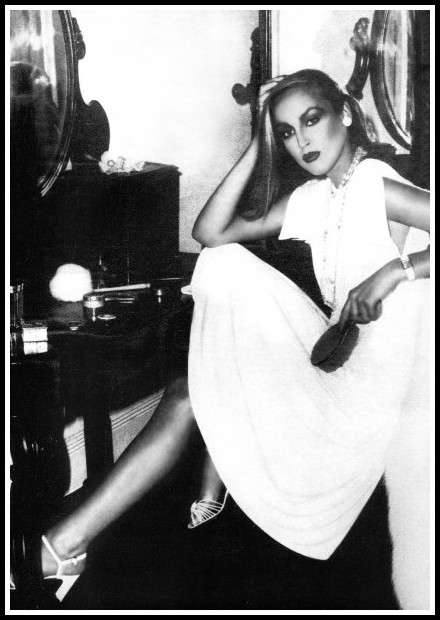

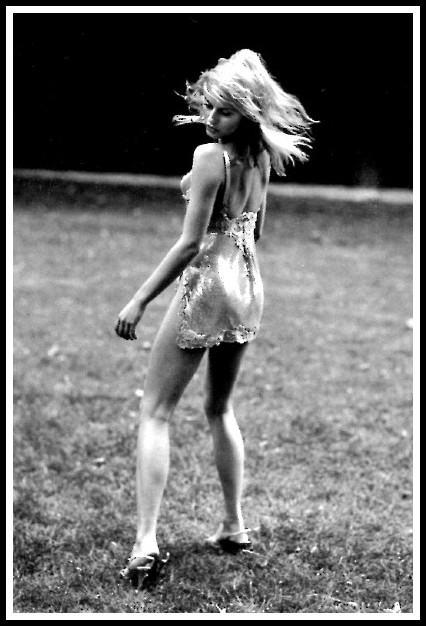

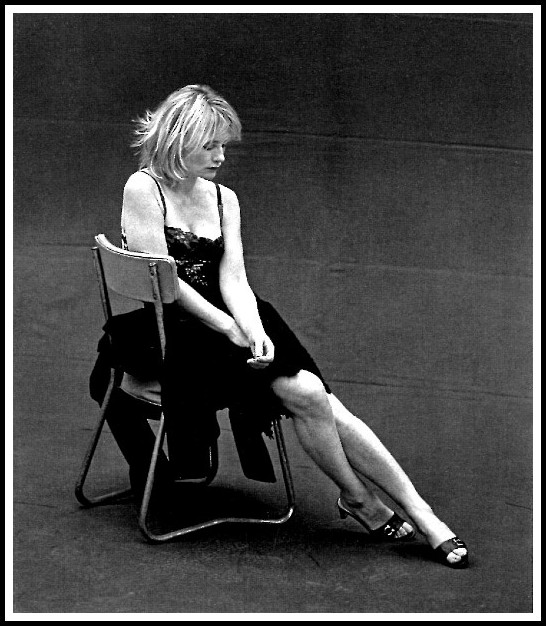

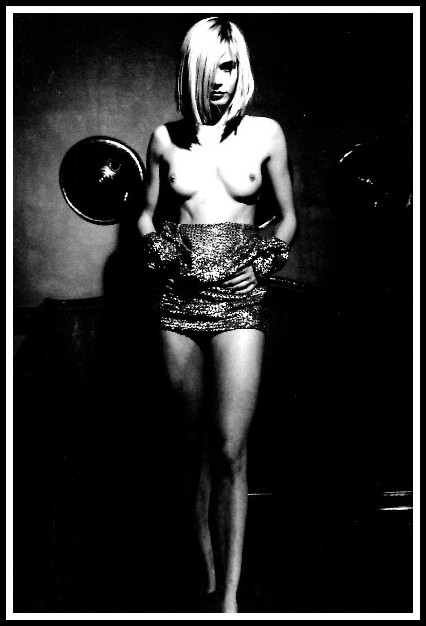

Rico Puhlmann, Jerry Hall, 1975

Cohen and his commentators1 have pointed out that the impetus for ‘Take this Longing’ came from the poet’s frustrated desire for Nico. Leonard:

I walked into a club called the Dom and I saw someone singing there who looked like she inhabited a Nazi poster. It was Nico, the perfect Aryan ice queen. I just stood there and said forget the new society, this is the woman I’ve been looking for. I followed her all round New York. Nico eventually told me ‘Look, I like young boys. You’re just too old for me.’2

How might this fact help us interpret the lyrics of the song? I will argue that Nico is important here only to the extent that she reveals something of Leonard to himself. Jean Baudrillard:

What seduces you in the other is that the other is the site of your secret. Not the site of your likeness and certainly not of your truth—neither the hidden ideal-type of who you are nor the hidden ideal of what you lack but rather the site of what escapes you, through which you escape yourself, and escape from your own truth. A site of vertigo, not desire but vertigo, a site of neither alienation nor annihilation, but of eclipse, of appearance / disappearance, of a scintillation of being. That is at once your secret and the secret of seduction: a game of absence / presence, a duel around the centre of absence.3

From this perspective, then, Nico is the site of Leonard’s secret.

1 – See, for example, Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 154 and Christophe Lebold, Leonard Cohen: L’Homme qui voyait tomber les anges (Rosières-en-Haye, France: Camion Blanc, 2013) Kindle edition.

2 – Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 84

3 – Jean Baudrillard, ‘Les abîmes superficiels’ in Maurice Olender & Jacques Sojcher, La Séduction (Paris: Éditions Aubier Montaigne / Colloques de Bruxelles, 1980) pp. 202-03. Translated here by Richard Jonathan

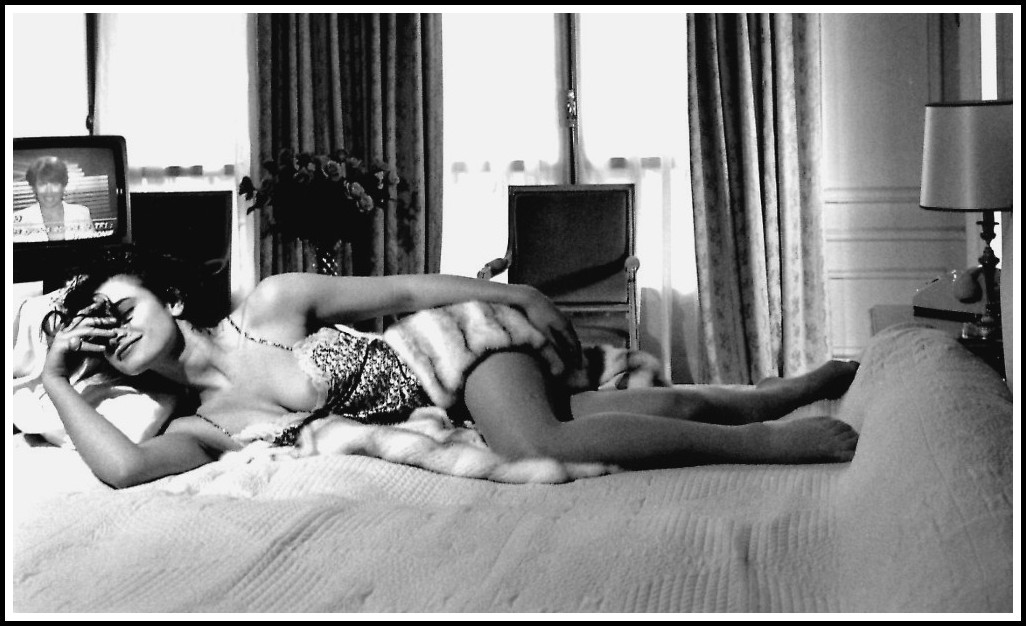

Vanity Fair photo: Patrick Demarchelier, Natalia Vodianova, 2005

Leonard Cohen: I was obsessed by gaining women’s favours at a certain point in my life and way beyond any reasonable activity. It became the most important thing in my life and it led me into very obsessive behaviour and some very interesting things, and probably most of the things I learned about myself and about other people were gained from this period of obsessiveness.1

It’s difficult in the face of desire to locate your authentic self. The object of your desire and the quality of your desire are so compelling that you are willing to twist yourself into any disguise in order to gain the object of your desire. This is something certainly all men know. It’s powerful and it is known as temptation. It is a very precarious and dangerous activity and after a while when you’re old enough to understand the consequences of your activity and you know that fucking with somebody is serious, on any level, that the moral question comes into being. But nevertheless, desire is so powerful that even with the knowledge of the consequences you will allow yourself to be driven into disguises.2

Though Leonard made these observations in 1988, he was, already in 1967, aware of what Nico was to him.

1 – Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 19

2 – Ibid., p. 20

Vanity Fair photo: Michael Thompson, Julianne Moore, 2000

Consider ‘Winter Lady’, another song where Nico’s presence might be felt, from Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967).

WINTER LADY

Leonard Cohen

Traveling lady stay awhile

Until the night is over

I’m just a station on your way

I know I’m not your lover

I lived with a child of snow

When I was a soldier

And I fought every man for her

Until the nights grew colder

She used to wear her hair like you

Except when she was sleeping

And then she’d weave it on a loom

Of smoke and gold and breathing

And why are you so quiet now

Standing there in the doorway?

You chose your journey long before

You came upon this highway

Traveling lady stay awhile

Until the night is over

I’m just a station on your way

I know I’m not your lover

‘I’m just a station on your way / I know I’m not your lover’; ‘You chose your journey long before / You came upon this highway’: Leonard sees Nico as a fellow pilgrim, and in his lucidity he understands that all he can ever hope for from her is that she ‘stay awhile [in his bed] until the night is over’.

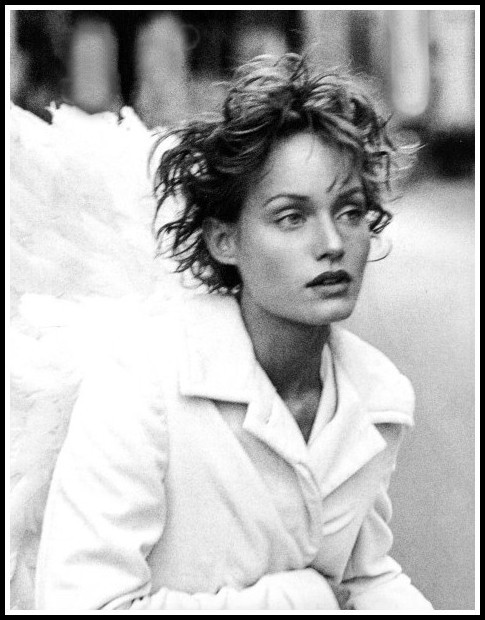

Peter Lindbergh, Amber Valletta, 1993

‘What seduces you in the other is that the other is the site of your secret’: It is interesting to note the similarities between the two most significant women—Marianne and Nico—who were ‘the site of Leonard’s secret’ during the 1960s. In ‘Winter Lady’, Marianne is the ‘child of snow’ whose hair when she was sleeping1 she’d weave ‘on a loom / Of smoke and gold and breathing’. Marianne ‘used to wear her hair like you’, Leonard tells Nico, ‘except when she was sleeping’. Other similarities: Both Marianne and Nico, as Christophe Lebold points out,2 were women who lived with a young son whom the father had abandoned. And each was an ‘Aryan’ beauty, with Marianne, in her care for Leonard, an angel of life and Nico, with her childhood under the Nazis, an angel of death. Marianne the ‘child of snow’, then, and Nico the ‘winter lady’. Let us now turn to the lyrics of ‘Take this Longing’.

1 – As in ‘the sleepy golden storm’ of ‘Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye’.

2 – Christophe Lebold, Leonard Cohen: L’Homme qui voyait tomber les anges (Rosières-en-Haye, France: Camion Blanc, 2013) Kindle edition.

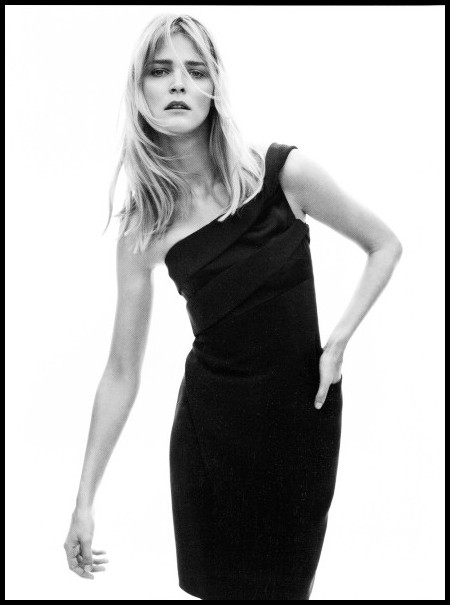

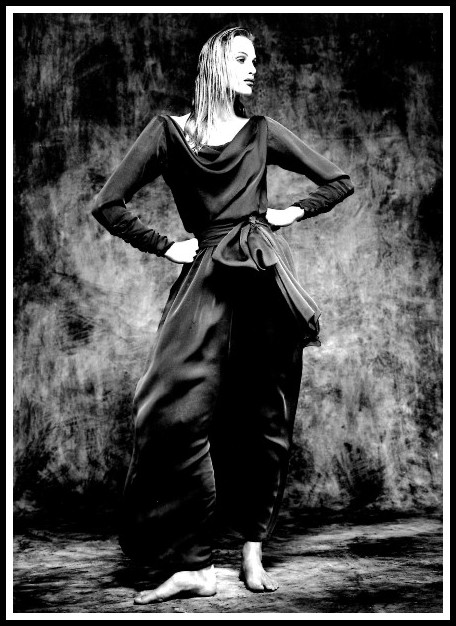

Vogue photo: Josh Olins, 2010

1. Many men have loved the bells / You fastened to the rain. Bells celebrate the living, mourn the dead and break the lightning; purification, exorcism and warning may inhere in their ringing. Rain is fecundation and blessing; perhaps in every drop there is an angel. The woman wilfully fastens the bells to the rain. Is she issuing a warning to stay away or an invitation to approach?

2. And everyone who wanted you / They found what they will always want again. At once Tantalus and Sisyphus, the men in pursuit of the woman are condemned to a frustration and repetition that, paradoxically, they experience as ennobling.

3. Your beauty lost to you yourself / Just as it was lost to them. Freud wrote somewhere that women love only themselves, that their self-sufficiency is their charm. The woman here is self-sufficient, but, in contrast to the usual pattern, she is not vain: she has no interest in impassioning men through her beauty, because to do so would be to alienate herself. If the man in his passion is hollowed out by frustration, that’s his problem, not hers: that, it would seem, is her view of the matter.

4. Take this longing from my tongue / Whatever useless things these hands have done. The man pleads for a kiss that would at once end the torment of his desire and redeem the abuse he has inflicted on himself in frustration.

Vogue photo: Robert Erdmann, Anne Morton, 1996

5. Let me see your beauty broken down / Like you would do for one you love. Without comment, I offer here these passages from Georges Bataille’s reflection of eroticism and beauty:1

Together with an effort to reach continuity by breaking with individual discontinuity, the search after beauty entails an effort to escape from continuity. The twofold effort is never at an end: its ambiguity crystallizes and carries onward the workings of eroticism.

If beauty so far removed from the animal is passionately desired, it is because to possess is to sully, to reduce to the animal level. Beauty is desired in order that it may be befouled; not for its own sake, but for the joy brought by the certainty of profaning it.

No-one doubts the ugliness of the sexual act. Just as death does in sacrifice, the ugliness of the sexual union makes for anguish. But the greater the anguish—within the measure of the partners’ strength—the stronger the realization of exceeding the bounds and the greater the accompanying rush of joy. Tastes and customs vary, but that cannot prevent a woman’s beauty (her humanity, that is) from making the animal nature of the sexual act obvious and shocking.

1 – Georges Bataille, Eroticism, tr. Mary Dalwood (London: Penguin Books, 2001 [1962/1957] pp. 144-45

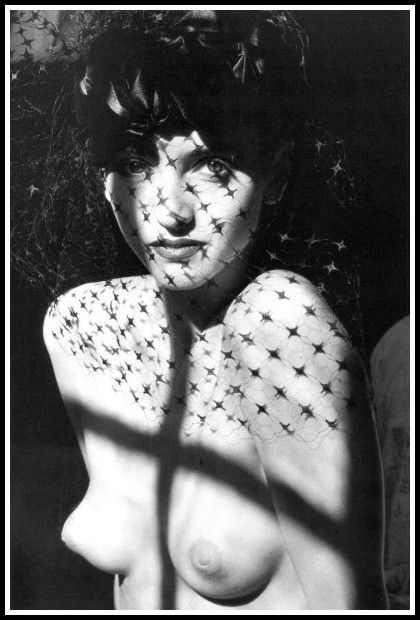

Photo: Javier Valhenrat, 2009 (desaturated, detail)

6. Your body like a searchlight / My poverty revealed. Here, a passage from Giorgio Agamben1 may stimulate an interpretation.

One could define nudity as the envelopment that reaches a point where it becomes clear that clarification is no longer possible. It is in this sense that we must understand Goethe’s maxim, according to which ‘beauty can never clarify itself.’ Only because beauty remains to the end an ‘envelopment,’ only because it remains ‘inexplicable’, can appearance—which reaches its supreme stage in nudity—be called beautiful. That nudity and beauty cannot be clarified does not therefore mean that they contain a secret that cannot be brought to light. Such an appearance would be mysterious, but precisely for this reason it would not be an envelopment, since in this case one could always continue to search for the secret that is hidden within it. In the inexplicable envelopment, on the other hand, there is no secret; denuded, it manifests itself as pure appearance. The matheme of nudity is: there is nothing other than this. Yet it is precisely the disenchantment of beauty in the experience of nudity, this sublime but also miserable exhibition of appearance beyond all mystery and all meaning, that can somehow allow us to see, beyond the prestige of grace and the chimeras of corrupt nature, a simple, inapparent human body. This simple dwelling of appearance in the absence of secrets is its special trembling—it is the nudity that signifies nothing and, precisely for this reason, manages to penetrate us.

1 – Giorgio Agamben, Nudities, tr. David Kishik & Stefan Pedatella (Stanford, California: Stanford University Press, 2011) pp. 89-90

Herb Ritts, Kim Basinger, 1989

7. I would like to try your charity / Until you cry, ‘Now you must try my greed’. In the mode of greed the woman fully inhabits her body and coincides with her self. In the mode of charity, she is displaced from her self and is not at home in her body. If we return to Bataille as cited in #5, we see that a woman in the mode of greed is far more erotic since, in assuming her beauty, she offers her lover more to befoul.

8. And everything depends upon / How near you sleep to me. When the lights are out, touch takes over from sight, silence from sound, scent and taste from sterile distance, enabling the body to communicate in ways words cannot, bringing new possibilities into being.

9. Let me see your beauty broken down / Like you would do for one your love. An alternative stimulant to interpretation of this line from that of Georges Bataille cited in #5 is provided, again, by Giorgio Agamben:1

The ‘nihilism of beauty,’ common to many beautiful women, consists in reducing one’s own beauty to pure appearance and then exhibiting this appearance with a sort of remote sadness, stubbornly denying the idea that beauty can signify something other than itself. But it is precisely the very lack of illusions about itself—this nudity without veils that beauty thus manages to achieve—that furnishes the most frightful attraction. This disenchantment of beauty, this special nihilism, reaches its extreme stage with fashion models, who learn before all else to erase all expression from their faces. In so doing, their faces become pure exhibition value and, as a result, acquire a particular allure.

1 – Giorgio Agamben, Nudities, tr. David Kishik & Stefan Pedatella (California: Stanford University Press, 2011) p. 88

Iris van Berne, Giorgio Armani RTW SS 2012

10. Hungry as an archway / Through which the troops have passed. This evocative simile is akin, in the way it works, to Cohen’s ‘Summer Haiku’:

Silence

and a deeper silence

when the crickets

hesitate

It might be rewritten thus:

Hunger:

An archway

through which the troops

have passed

The thirst evoked by ‘take this longing from my tongue’ is now the hunger of a wide-open mouth, filled with emptiness. Note the military motif of ‘troops’, echoing, for example, the ‘When I was a soldier / And I fought every man for her’ of ‘Winter Lady’. Leonard Cohen:

‘Any man over thirty knows that there’s a war between men and women, a fight to the death. That is, a fight to the psychic death, a struggle for supremacy and a ruthless and vicious contest of wills.’1

1 – Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 19. Note that Cohen made this statement in 1974, the year of ‘Take this Longing’ and the album New Skin for the Old Ceremony.

Juergen Teller, Isabelle Huppert, 2001

11. I stand in ruins behind you / With your winter clothes, your broken sandal strap. This line echoes ‘And why are you so quiet now / Standing there in the doorway’ from ‘Winter Lady’, and a comparison of the two lines enables us to take the measure of Cohen’s shift from a focus on the woman to a focus on the man: he is aware that she is the site of his secret. It is he that is ‘in ruins’, awaiting, in alchemical terms, transmutation (via the union of opposites, man and woman) from the solve et coagula state he currently is in. The ‘winter clothes’ promise protection, a flight from desire, while the ‘broken sandal strap’, evoking the allure of the foot the sandal both conceals and reveals, suggests the lover is not done with desire. And indeed, the next line confirms this.

12. I love to see you naked over there / Especially from the back. A naked woman seen from the back gives freer rein to the imagination than would a full frontal view of her. This predilection for a rear view reinforces the shift from the woman to the man: it is he who seeks, via sexual union with the woman, ‘the stopping of the mind stuff to breathe the breath of the Eternal’, as the introvertive tradition of mysticism1 would have it. Here, as in all of Leonard’s work, the lover is first and foremost a pilgrim.

13. Untie for me your hired blue gown / Like you would do for one that you love. Here, the man acknowledges that the woman bears him no love, but refuses to accept defeat in seduction: he asks her to grant him his wish to see her naked. Note that the ‘hired blue gown’ indicates the ephemerality of the role she is now playing for him: she too is a pilgrim, as we saw in ‘Winter Lady’; she too is only ‘passing through’.

1 – See the Encyclopedia Britannica article on ‘Mysticism’.

Paolo Roversi, Isabelle Huppert, 2005

15. You’re faithful to the better man / I’m afraid that he left. If we accept that Leonard and Nico are the protagonists of the song, then the ‘better man’ is Jim Morrison,1 * or perhaps Jimi Hendrix.2

15. So let me judge your love affair / In this very room where I have sentenced mine to death. Leonard rarely casts himself in the role of judge—he has a heightened sense of ethics (what you done when you are alone) but he is not a moralist (what you do when others are watching)—but, having passed judgement and sentence on his own love affair (the one-way ‘affair’ with the woman in the song?), he enacts a slow ritual of letting go, asking for just one fuck—even if only verbal (judging) and vicarious (your love affair)—by way of goodbye.

16. I’ll even wear these old laurel leaves / That he’s shaken from his head. Leonard in his desperation is willing to descend to self-abasement, to efface himself in the disguise of the lover who left.3

1 – Christophe Lebold, Leonard Cohen : L’Homme qui voyait tomber les anges (Rosières-en-Haye, France : Camion Blanc, 2013) Kindle edition.

* Richard Witts, in his biography of Nico—incidentally, along with James Young’s Nico: Songs They Never Played on the Radio, the best book on Christa Päffgen—quotes her as saying: ‘It was fascinating and frightening. Jim Morrison had the best sex I ever had inside me.’ Richard Witts, Nico: Life and Lies of an Icon (London: Penguin-Random House / Virgin Books / Ebury Publishing, 1993). Kindle Edition.

2 – Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) pp. 153-54

3 – Recall Leonard’s remark, cited earlier: ‘You are willing to twist yourself into any disguise in order to gain the object of your desire’.

Sylvia Plachy, Isabelle Huppert, 1986

17. Let me see your beauty broken down / Like you would do for one you love. For the third and final time we return to this line. What else might it mean? I offer these reflections by Francette Pacteau,1 which I find highly illuminating.

I am interested less in the contingent object of desire than the fantasy which frames it. Since formulations of feminine beauty by men appear to be largely unselfconscious, I take the step of supposing that they might indeed be unconsciously motivated. In other words, the variety of formulations of what is recognized as beauty in a woman would correspond to a variety of (mainly) masculine symptoms. (The term ‘symptom’ here has to be understood in the fully psychoanalytic sense of the word, as indicative of a repressed past.)

In Civilization and its Discontents, Freud suggests that, ‘The love of beauty seems a perfect example of an impulse inhibited in its aim.’ He thus points us to the fantasmatic dimension of the experience of beauty. It is a dimension in which we turn from the object of instinct to the object of drive; from the possibility of a one-off satisfaction of need to the impossibility of fulfilment of desire; it is a dimension in which desire, forever invoking interdiction and loss, is articulated in processes of defence and the production of symptoms.

How a man perceives a woman’s beauty, then, offers an indication of what in his past he is repressing. Her beauty is his symptom. This insight confirms Baudrillard’s thesis that ‘what seduces a man in a woman is that she is the site of his secret’. An interpretation of this dynamic in ‘Take this Longing’ could be that, if Leonard gets his way, Jew and Nazi, Leonard and Nico, would—in Leonard’s phantasy—engage in the kind of eroticism we see in, for example, Liliana Cavani’s The Night Porter.2 Whatever the case may be, the song, as I’ve tried to show, is one of Leonard’s finest.3

1 – Francette Pacteau, The Symptom of Beauty (London: Reaktion Books, 1994) pp. 15-18

2 – The Night Porter, incidentally, was released in the same year as ‘Take this Longing’ and New Skin for the Old Ceremony.

3 – Leonard himself confirms this: ‘I must say I’m pleased with the album [New Skin for the Old Ceremony]. It’s good. I’m not ashamed of it and I’m ready to stand by it. Rather than think of it as a masterpiece, I prefer to look at it as a little gem.’ Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 62.

Peter Lindbergh, Isabelle Huppert, 2002

4. TRUE LOVE LEAVES NO TRACES | JE T’AIME MOI NON PLUS

TRUE LOVE LEAVES NO TRACES

Leonard Cohen

As the mist leaves no scar

On the dark green hill

So my body leaves no scar

On you and never will

Through windows in the dark

The children come, the children go

Like arrows with no targets

Like shackles made of snow

True love leaves no traces

If you and I are one

It’s lost in our embraces

Like stars against the sun

As a falling leaf may rest

A moment on the air

So your head upon my breast

So my hand upon your hair

And many nights endure

Without a moon, without a star

So we will endure

When one is gone and far

True love leaves no traces

If you and I are one

It’s lost in our embraces

Like stars against the sun

JE T’AIME MOI NON PLUS

Serge Gainsbourg

Je t’aime, je t’aime, oui je t’aime

Moi non plus

Oh, mon amour

Comme la vague irrésolue

Je vais, je vais et je viens, entre tes reins

Je vais et je viens, entre tes reins

Et je me retiens

Je t’aime, je t’aime, oui je t’aime

Moi non plus

Oh mon amour, tu es la vague

Moi, l’île nue

Tu vas, tu vas et tu viens, entre mes reins

Tu vas et tu viens, entre mes reins

Et je te rejoins

Je t’aime, je t’aime, oh oui je t’aime

Moi non plus

Oh, mon amour

Comme la vague irrésolue

Je vais, je vais et je viens, entre tes reins

Je vais et je viens, entre tes reins

Et je me retiens

Tu vas, tu vas et tu viens, entre mes reins

Tu vas et tu viens, entre mes reins

Et je te rejoins

Je t’aime, je t’aime, oh oui je t’aime

Moi non plus

Oh, mon amour

L’amour physique est sans issue

Je vais, je vais et je viens, entre tes reins

Je vais et je viens, je me retiens

Non, maintenant, viens

Bettina Rheims, Alexa in Hôtel Crillon, 1989

The opening song on Death of a Ladies’ Man, ‘True Love Leaves No Traces’ is an oasis of grace in the desert of ‘dis-grace’ that is the remainder of the album. The lyric is infused with the Zen aesthetic: a state of flux, impermanence, and presence-in-the-moment characterize it, as do simplicity, clarity, and understatement. Leonard’s stays at the Mount Baldy monastery are only the most obvious indications of his affinity with Zen. In ‘Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye’, the line, ‘You know my love goes with you / As your love stays with me / It’s just the way it changes / Like the shoreline and the sea’, testifies, in its ‘elegant simplicity and articulate brevity’, to the poet’s ‘active calm’ in the face of ‘constant change’—Zen values par excellence. And yet, when it comes to love and sex, is Zen not an impossible ideal? All the other songs on Death of a Ladies’ Man answer ‘Yes’, as does Leonard himself, remember: ‘There’s a war between men and women, a fight to the death. That is, a fight to the psychic death, a struggle for supremacy and a ruthless and vicious contest of wills.’1 A Zen love relationship or sexual encounter, then, is at best an aspiration. This is exactly what Serge Gainsbourg, in his song, says, although through very different poetic means.

1 – Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 19.

Jeanloup Sieff, Portrait with Veil, 1985

Lyrically, the genius of ‘Je t’aime moi non plus’ is that it is at once a celebration of and a requiem for love and sex. Where Leonard the pilgrim pursues love and sex as a means to redemption, Serge the cynic declares his disillusionment with both.1 Written during the height of his fling with Brigitte Bardot,2 the song’s heavy breathing caught the public’s attention, while the two lines that speak to its essence went largely unattended. The first, sung by Serge in response to Brigitte or Jane’s ‘Je t’aime’ is, of course, ‘moi non plus’: ‘I love you’ – ‘Neither do I’. Beyond cynicism, the insight is profound, for, as Adam Phillips notes:3

In Freud’s vision we are, above all, ambivalent animals: wherever we hate we love, wherever we love we hate. If someone can satisfy us, they can frustrate us; and if someone can frustrate us we always believe they can satisfy us. Ambivalence does not, in the Freudian story, mean mixed feelings, it means opposing feelings. Love and hate – a too simple vocabulary, and so never quite the right names – are the common source, the elemental feelings with which we apprehend the world; they are interdependent in the sense that you can’t have one without the other, and that they mutually inform each other. The way we hate people depends on the way we love them and vice versa. According to psychoanalysis these contradictory feelings enter into everything we do. We are ambivalent, in Freud’s view, about anything and everything that matters to us; indeed, ambivalence is the way we recognise that someone or something has become significant to us. This means that we are ambivalent about ambivalence, about love and hate and sex and pleasure and each other and ourselves, and so on; wherever there is an object of desire there must be ambivalence.

Both Serge and Leonard highlight this ambivalence about love and sex, and both in multiple songs, but never, in popular music, has this been done as concisely and incisively as in ‘Je t’aime moi non plus’.

1 – It is not for nothing that Gainsbourg’s favourite novel is Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe. See Bertrand Dicale, Serge Gainsbourg en dix leçons (Paris: Fayard, 2009) Kindle Edition.

2 – Loïc Picaud & Gilles Verlant, L’intégrale Gainsbourg: L’histoire de toutes ses chansons (Paris: Éditions Fetjaine, 2011) pp. 265-66

3 – Adam Phillips, ‘Against Self-Criticism’. London Review of Books Vol. 37 No. 5 · 5 March 2015.

Bettina Rheims, Anna Karina, 1988

The second line that speaks of the essence of ‘Je t’aime moi non plus’ is ‘L’amour physique est sans issue’. The most elegant translation of the line is, perhaps, ‘Physical love has no strings attached’, yielding by extension the interpretation, ‘One can make love without love’. When Jane Birkin left Serge Gainsbourg, Serge, in writing the song ‘Physique et sans issue’ for her, did not change his tune but did acknowledge that things are more complicated, as these lines from that lyric show:

L’amour physique est sans issue / Tu le sais, ouais, toi non plus

Je t’aime et toi-même, dis-moi que tu m’aimes / Dis-le-moi, si même cela n’est pas vrai

À dire vrai, il n’y en a pas des masses / De belles histoires de cœur

We are back, then, to the theme of ambivalence in love and sex, and again I assert that ‘Je t’aime moi non plus’ expresses that theme more excitingly—physically and intellectually—than any other song (perhaps) in popular music. Its simultaneous incarnation—in both words and music—of rave-up and requiem, eulogy and elegy, illusion and disillusion, has no match in the song repertoire. Except, of course, in that of Leonard Cohen.

Bettina Rheims, Suzanna pulls down her dress, 1988

5. SO LONG, MARIANNE | JE SUIS VENU TE DIRE QUE JE M’EN VAIS

SO LONG, MARIANNE

Leonard Cohen

Come over to the window my little darling

I’d like to try to read your palm

I used to think I was some kind of Gypsy boy

before I let you take me home

Now so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

Well you know that I love to live with you

but you make me forget so very much

I forget to pray for the angels

and then the angels forget to pray for us

Now so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

We met when we were almost young

deep in the green lilac park

You held on to me like I was a crucifix

as we went kneeling through the dark

Oh so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

Your letters they all say that you’re beside me now

Then why do I feel alone?

I’m standing on a ledge and your fine spider web

is fastening my ankle to a stone

Now so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

For now I need your hidden love

I’m cold as a new razor blade

You left when I told you I was curious

I never said that I was brave

Oh so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

Oh, you’re really such a pretty one

I see you’ve gone and changed your name again

And just when I climbed this whole mountainside

to wash my eyelids in the rain

Oh so long, Marianne, it’s time that we began

to laugh and cry and cry and laugh about it all again

JE SUIS VENU TE DIRE QUE JE M’EN VAIS

Serge Gainsbourg

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Et tes larmes n’y pourront rien changer

Comme dit si bien Verlaine au vent mauvais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tu t’souviens des jours anciens et tu pleures

Tu suffoques, tu blêmis à présent qu’a sonné l’heure

Des adieux à jamais

Oui je suis au regret

De te dire que je m’en vais

Je t’aimais, oui, mais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tes sanglots longs n’y pourront rien changer

Comme dit si bien Verlaine au vent mauvais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tu t’souviens des jours heureux et tu pleures

Tu sanglotes, tu gémis à présent qu’a sonné l’heure

Des adieux à jamais

Oui je suis au regret

De te dire que je m’en vais

Car tu m’en a trop fait

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Et tes larmes n’y pourront rien changer

Comme dit si bien Verlaine au vent mauvais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tu t’souviens des jours anciens et tu pleures

Tu suffoques, tu blêmis à présent qu’a sonné l’heure

Des adieux à jamais

Je suis au regret

De te dire que je m’en vais

Oui, je t’aimais, oui, mais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tes sanglots longs n’y pourront rien changer

Comme dit si bien Verlaine au vent mauvais

Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais

Tu t’souviens des jours heureux et tu pleures

Tu sanglotes, tu gémis à présent qu’a sonné l’heure

Des adieux à jamais

Oui, je suis au regret

De te dire que je m’en vais

Car tu m’en as trop fait

Bettina Rheims, Johanna in Yves Saint-Laurent, 1989

Everything is at hand to interpret ‘So Long, Marianne’; therefore, instead of articulating an interpretation, I offer the following four items.

DAYS OF KINDNESS

Leonard Cohen

Greece is a good place

to look at the moon, isn’t it

You can read by moonlight

You can read on the terrace

You can see a face

as you saw it when you were young

There was good light then

oil lamps and candles

and those little flames

that floated on a cork in olive oil

What I loved in my old life

I haven’t forgotten

It lives in my spine

Marianne and the child

The days of kindness

It rises in my spine

and it manifests as tears

I pray that a loving memory

exists for them too

the precious ones I overthrew

for an education in the world

Hydra, 19851

1 – Leonard Cohen, Stranger Music: Selected Poems and Songs (New York: Vintage Books, 1994) p. 401

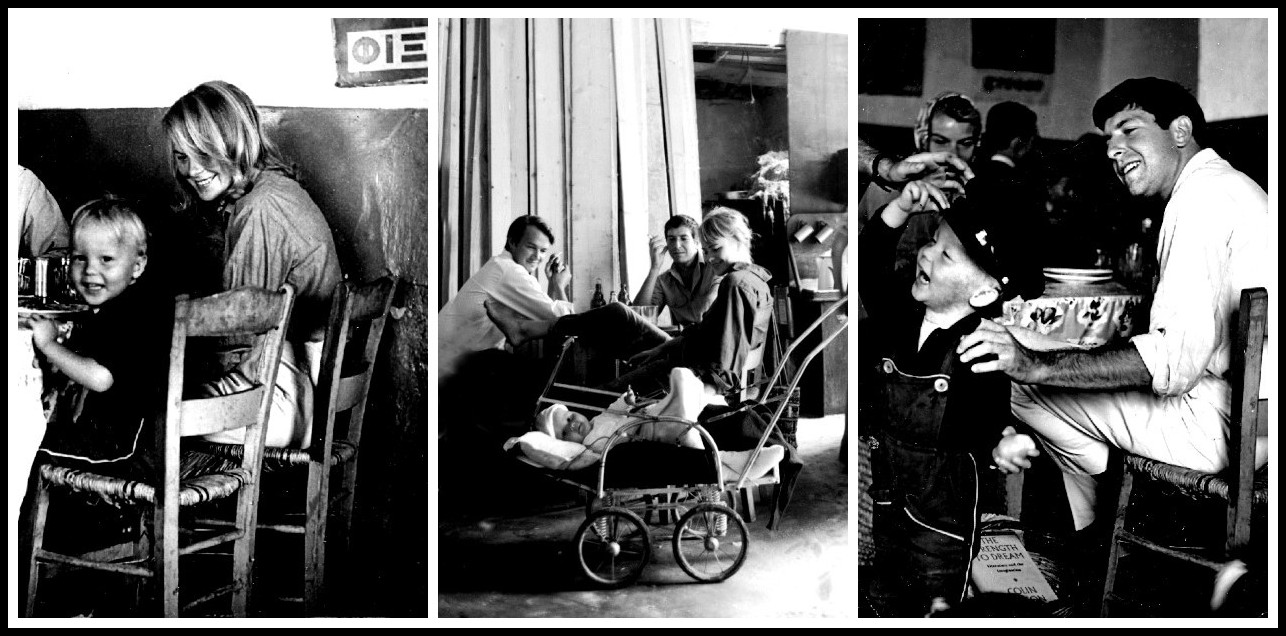

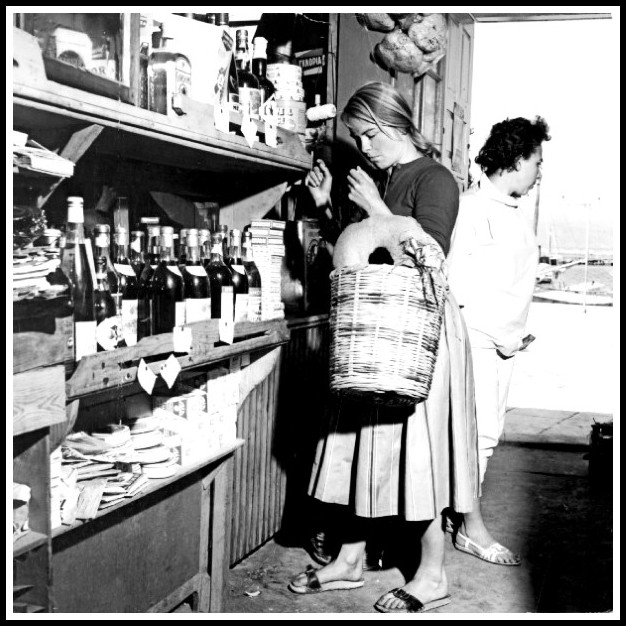

Leonard Cohen, Marianne Ihlen, Axel Jensen, baby Axel | Hydra 1960

LEONARD ON MARIANNE

She brought a tremendous sense of order into my life. It was really a great privilege to live in a house with her. She had been brought up by her grandmother in the war so she had the education of an older generation. Just the way that she laid a table or lit candles or cleaned the house, and she wasn’t by any means confined to these activities that have come under the suspicion of feminists. It wasn’t just that she was the Muse, shining in front of the poet. She understood that it was a good idea to get me to my desk.1

1 – Quoted in Jim Devlin, ed., Leonard Cohen in His Own Words (UK: Omnibus Press, 1998) p. 17

Marianne shopping in Hydra, 1960

MARIANNE ON LEONARD

All that Marianne will say about the end of the affair is, ‘To me he was still the same, he was a gentleman, and he had that stoic thing about him and that smile he will try to hide behind – “Am I serious now or is all this a joke?” We were in love and then the time was up. We were always friends, and he still is my dearest friend and I will always love him. I feel very lucky to have met Leonard at that time in my life. He taught me so much, and I hope I gave him a line or two.’2

2 – Quoted in Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 194

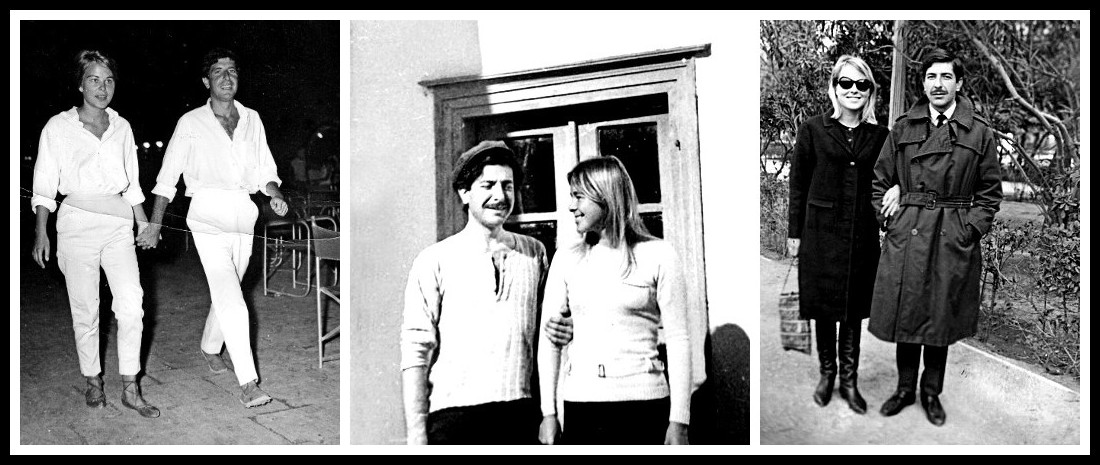

Leonard Cohen & Marianne Ihlen | Hydra 1963 | Hydra 1965 | Athens 1965

LEONARD IN TEARS

Marshall took Leonard aside. ‘We have to take care of business and finish the show or we might not get out of here in one piece.’ Leonard said, ‘I think what I need is a shave.’ That’s what his mother had told him to do when things got bad. There was a mirror and a basin in the dressing room and someone fetched him a razor. Slowly, serenely, while the crowd clapped and sang in the auditorium, Leonard shaved. When he was done, he smiled. They went back on stage. As Leonard sang ‘So Long, Marianne’, immersing himself in the song he’d written to a woman in a moment in a different, less complicated time, changing her description from ‘pretty one’ to ‘beautiful one’, tears began to run down his face.1

1 – Quoted in Sylvie Simmons, I’m Your Man: The Life of Leonard Cohen (London: Vintage, 2012/2016) p. 250.

The scene is captured in Tony Palmer’s excellent documentary of Leonard’s 1972 European tour, available on DVD: Leonard Cohen: Bird on a Wire, Tony Palmer, director. France: Blaq Out, 2017.

Marianne Ihlen, Hydra, 1963

Gainsbourg’s ‘Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais’ is akin to his ‘L’Eau à la bouche’ in that both songs, in their ravishing arrangements, capture a mood with great precision: ‘gentlemanly lust’ in ‘L’Eau’; the pathos of breaking up in ‘Je suis venu’. The two songs also exude a seductive charm, and both partake of the exercise de style. In contrast to their respective Cohen counterparts, ‘So Long, Marianne’ and ‘Take this Longing’, both Gainsbourg songs, in terms of the attitude expressed in the lyrics, are generic. Indeed, where Leonard’s songs attain a universality through their individuality, Serge’s attain universality through their generic quality. I would argue that Leonard’s lyrics reach deeper than Serge’s precisely because they are drawn from the poet’s subjectivity; they invite us to reach into ourselves to find parallels to the experience the song is articulating. In Serge’s songs, the ‘instant gratification’ of sympathizing with the generic sentiment is, however, counter-balanced by the delight the highly-wrought lyrics procure, both sensually and intellectually.

Bettina Rheims, Lio and the Refrigerator, 1986

What is striking in both songwriters is the economy of means by which they achieve their effects. Leonard typically resorts to metaphor and Serge to the intricacies of poetic construction. ‘Je suis venu te dire que je m’en vais’ is based on Verlaine’s ‘Chanson d’automne’.

CHANSON D’AUTOMNE

Paul Verlaine

Les sanglots longs

Des violons

De l’automne

Blessent mon cœur

D’une langueur

Monotone.

Tout suffocant

Et blême, quand

Sonne l’heure,

Je me souviens

Des jours anciens

Et je pleure ;

Et je m’en vais

Au vent mauvais

Qui m’emporte

Deçà, delà,

Pareil à la

Feuille morte.

From Verlaine Serge took diction, sonority, and rhythm, as well as the overall mood of the poem, while displacing the ‘je’ and introducing a ‘tu’. Particularly fine is the variation Serge brings to the verses, with ‘larmes’ alternating with ‘sanglots’, ‘jours anciens’ with ‘jours heureux’, ‘tu suffoques’ with ‘tu sanglotes’, ‘tu blêmis’ with ‘tu gémis’, and ‘je t’aimais, oui, mais’ with ‘car tu m’en as trop fait’. If a generic sentiment can never be as incisive as an individualized one, Serge’s exquisitely crafted lyric nevertheless challenges us to look deeper into ourselves.

Bettina Rheims, Alison Cohn, 1986

6. CHELSEA HOTEL #2 | LA JAVANAISE

CHELSEA HOTEL #2

Leonard Cohen

I remember you well in the Chelsea Hotel

You were talking so brave and so sweet

Giving me head on the unmade bed

While the limousines wait in the street

Those were the reasons, and that was New York

We were running for the money and the flesh

And that was called love for the workers in song

Probably still is for those of them left

But you got away, didn’t you, baby

You just turned your back on the crowd

You got away, I never once heard you say

I need you, I don’t need you

I need you, I don’t need you

And all of that jiving around

I remember you well in Chelsea Hotel

You were famous, your heart was a legend

You told me again you preferred handsome men

But for me you would make an exception

And clenching your fist for the ones like us

Who are oppressed by the figures of beauty

You fixed yourself, you said, ‘Well, never mind

We are ugly but we have the music’

And then you got away, didn’t you, baby

You just turned your back on the crowd

You got away, I never once heard you say

I need you, I don’t need you

I need you, I don’t need you

And all of that jiving around

I don’t mean to suggest that I loved you the best

I can’t keep track of each fallen robin

I remember you well in Chelsea Hotel

That’s all, I don’t even think of you that often

LA JAVANAISE

Serge Gainsbourg

J’avoue j’en ai bavé pas vous

Mon amour

Avant d’avoir eu vent de vous

Mon amour

Ne vous déplaise

En dansant la Javanaise

Nous nous aimions

Le temps d’une

Chanson

À votre avis qu’avons-nous vu

De l’amour?

De vous à moi vous m’avez eu

Mon amour

Ne vous déplaise

En dansant la Javanaise

Nous nous aimions

Le temps d’une

Chanson

Hélas avril en vain me voue

À l’amour

J’avais envie de voir en vous

Cet amour

Ne vous déplaise

En dansant la Javanaise

Nous nous aimions

Le temps d’une

Chanson

La vie ne vaut d’être vécue

Sans amour

Mais c’est vous qui l’avez voulu

Mon amour

Ne vous déplaise

En dansant la Javanaise

Nous nous aimions

Le temps d’une

Chanson

Peter Lindbergh, Julianne Moore, 2004

Both ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’ and ‘La Javanaise’ speak of brief encounters between a man (the singer) and a woman. While both songs are individualized, it is only Leonard’s that is particularized: place and action are described in concrete terms, enabling the lyric to move organically from the physical to the metaphysical. In Serge’s song, only the phrase ‘en dansant la Javanaise’ suggests action, but that action is no more real than that of a wind-up ballerina on a birthday cake. ‘Chelsea Hotel #2’, in contrast, is raw in its evocation of reality: ‘giving me head on the unmade bed’; ‘clenching your fist… you fixed yourself’. From action, Leonard’s lyric moves to interpretation: ‘We were running for the money and the flesh / And that was called love for the workers in song’; ‘…for the ones like us / Who are oppressed by the figures of beauty / We are ugly but we have the music’. And at the centre of the song, of course, is the woman’s (Janis Joplin’s) death by overdose. We see, then, that Leonard’s song is multi-dimensional: a horizontal dimension made up of the action, and a vertical dimension made up of the interpretation. As mentioned in the introduction, in Leonard’s songs the vertical dimension is often the axis mundi that enables movement between underworld, earth and heaven; here, the only hint of another realm is the (modified) biblical image of the ‘fallen robin’. Richness of this kind is absent from Serge’s song; instead, he gives us the richness of his poetic construction, wherein no syllable is idle, each has work to do in his jeweled sound mosaic: Serge’s hyper-aestheticization of the word, with each syllable a sound-gem, partakes of an art-for-art’s sake decadence, as in Beardsley and Klimt.

Sylvia Plachy, Isabelle Huppert, 1986

Along with this verbal sophistication, we find, as always, the Gainsbourg persona: the pride and bitterness of the eternal outsider; the Bogart-like blend of toughness and tenderness; the disillusioned cynic hungry for love. This, then, is the stance Serge adopts in ‘La Javanaise’, and if you’re a Dylan fan, you may recognize that the attitude in Gainsbourg’s lyric is exactly that of Dylan’s in ‘Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right’. This hint of little-boy-lost inside hardboiled-hero is never to be found in Leonard Cohen, simply because Leonard is not given to attitudinizing. He never denies his responsibility in relationships, never diminishes the woman to elevate the man. We see, then, that in terms of what the song says—and not how it says it—there is often a complacency in Serge’s lyrics, a complacency never found in Leonard’s.

Sylvia Plachy, Isabelle Huppert, 1986

IV. CONCLUSION

So, dear reader, to what extent has this experiment in comparison enabled us to see aspects of Leonard Cohen’s and Serge Gainsbourg’s songs from a fresh perspective? For my part, the comparative approach had proved to be surprisingly effective: I would not have gained certain insights had I not resorted to this method. I hope you have found my essay both entertaining and instructive, and I welcome your comments—in English or French—in the comments box below.

Jean-Philippe Charbonnier, Isabelle Huppert, 1984

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments