Albéniz

Iberia

JEAN-FRANÇOIS HEISSER ON ALBÉNIZ’S ‘IBERIA’

Liner notes by Jean-François Heisser to his recording of the work for Erato Disques, 1994. Translated by Stewart Spencer.

This recording is dedicated to the memory of two composers who died within months of each other, Olivier Messiaen and Maurice Ohana. Not only through his writings and his comments as a teacher but also through his enthusiastic advocacy of music that was then on the very fringes of the repertory, Olivier Messiaen established the credentials of a work—Albéniz’s Iberia—that has every right to a place in the pantheon of great music, while Maurice Ohana, for his part, regarded himself as the rightful heir to the Andalusian tradition. Ohana was taught the piano by Frank Marshall, professor of piano at Barcelona’s Granados Academy and also the teacher of Alicia de Larrocha, and, although a Frenchman by birth, was a Spaniard at heart, accounting Falla and Albéniz among his principal sources of inspiration.

Pablo Picasso, The Guitar Player, 1910

Pablo Picasso, Girl with a Mandolin, 1910

It is exactly a hundred years since Albéniz settled in Paris, where the world of music welcomed him with open arms, but where he himself came to feel both integrated and rootless. Loved and acknowledged by all (Dukas, Fauré, Chausson and even Debussy, contrary to what might have been said), he exuded enthusiasm, was unstintingly generous and rallied around him representatives of the most advanced adherents of modern music. As a person, Albéniz reminds one irresistibly of Liszt, of whom he was briefly a pupil: an adventurous youth, a brilliant career as a virtuoso and then withdrawal from the world and the search for absolute values. In fact, the public man concealed behind his jovial good humour not only a deep nostalgia for his native Spain (which treated him so disdainfully) but a fundamental doubt about his stature as a composer, judging his countless early works as worthy of only contempt. He conceived Iberia at a time when his health was already beginning to fail and did so, moreover, in an attempt to provide an answer to two specific questions: how to write an academic work in the manner of the great French composers who had left such a profound impression on him, autodidact that he was, and how to hymn a mythic Spain that he would never see again. The attraction exerted on Debussy and his contemporaries by La vega, the first piece in an incomplete cycle intended to be called L’Alhambra, was in itself sufficient to encourage him to pursue this particular course.

Iberia: Twelve New Impressions was written between December 1905 and August 1907 in Paris and Nice, where the composer spent a period of several months. Although completed within the space of two years, the distance covered by the work in terms of the composer’s stylistic development seems altogether immense, extending, as it does, from the apparent simplicity of Evocación to the alleged over-elaboration of the third and fourth volumes. Did Albéniz realise, when he wrote the earliest pieces, that this project would take him so far? The pianist Blanche Selva, who worked closely with him throughout the whole period of composition, was unable to persuade him to simplify the writing in certain passages, although the corrections she made to the score of Rondeña met with his approval. It was she, moreover, who gave the first performance of all four volumes, playing them successively at the Salle Pleyel in Paris (1906), at Saint-Jean-de-Luz in the Pyrenees (1907), at the home of the Princesse de Polignac (1908) and at the Salon d’Automne (February 1909). But it was not until December 1909, seven months after Albéniz’s death, that the great Spanish pianist Joaquin Malats gave Madrid audiences their first opportunity to hear the work complete.

Georges Braque, Man with a Guitar, 1911-12

Georges Braque, Woman with a Guitar, 1913

The popularity that certain more easily accessible pieces have always enjoyed (one thinks in particular of Triana and El Corpus en Sevilla, which soon became test pieces at the Paris Conservatoire) no doubt played a part in obscuring an overall view of the work and in marginalising pieces deemed too abstruse or unplayable. Posterity, even today, has all too often responded to only certain aspects of Iberia—its flashes of brilliance, its larger-than-life vitality, not to say its exoticism—and in doing so has ignored its dreamy or sombre aspects, its tragic and poignant accents. If Falla’s music is characterised by its brutal contrasts between light and shade, it is half-tones that dominate here, hesitation between major and minor tonalities and the subtlety of the most delicately nuanced sentiments. The choice of keys is decisive, since each of them brings its own specific colour and light: one thinks, for example, of the luminous F sharp major of El Corpus en Sevilla, a Lisztian use of the key (as in the Hungarian composer’s Bénédiction de Dieu dans la solitude) that clearly looks forward to the principal tonality of Messiaen’s Vingt regards sur l’ enfant Jésus.

The first volume (which originally included three other pieces, Prelude, Cadix and Sevilla) is cast in the form of a long crescendo-like introduction in which the instrument’s range is progressively explored. The nonchalant fandanguillo of Evocación and the tempestuous polo of El puerto bring us straight to this opening volume’s undisputed masterpiece, the monumental Corpus en Sevilla. For the first time, Albéniz exploits an unprecedented range of dynamic intensity from pppp to ffff, thereby opening the way to modern keyboard writing. These three pieces could follow each other without a break, so closely related are they in terms of their tonalities, descending in fifths through A flat, D flat and F sharp.

Georges Braque, Still Life (with Fruit and Ace of Clubs), 1913

Georges Braque, Still Life (The Pedestal Table), 1911

With the second volume (originally conceived in the reverse order, Triana, Almeria, Rondeña), the writing becomes more complex: there is systematic crossing of the hands in Rondeña, for example, and extremely strenuous polyphonic passages in Triana involving the interplay of timbre. But the most striking part of this triptych is without any doubt Almeria, a great nocturne whose swaying taranta rhythms carry the performer with them and charm and bewitch the listener. In the words of Blanche Selva, Almeria ‘never lets go of the pianist’.

Whereas the first two books—which are also the most widely performed—impose a sense of ascending movement on the work, the three pieces that make up the third volume, all equally powerful and equally weighty, mark the nec plus ultra of dramatic tension and pianistic writing. El Albaicín, one of the rare descriptive pieces included in the series, attests to the fascination exerted by Granada on the world of contemporary music (only Falla was able to fulfil the dream of returning of the well-spring of the cante hondo), while El polo and Lavapiés propel us abruptly into a world of experimentation, as Albéniz forces back the boundaries of the instrument’s possibilities, with vertiginous changes of register, extremes of dynamics and what might be termed a wilful ‘saturation’ of the sound in Lavapiés, all of which prefigure the modern keyboard style of Boulez’s Structures and Stockhausen’s Klavierstücke. For each of these three pieces, Albéniz added a dedication to the man he considered the greatest pianist of all, his friend Joaquin Malats, who died soon after the memorable first performance in Madrid. The composer’s intensity of feeling can be judged from the dedication to El polo: ‘To the most loved, to the unique, vibrant and universal artist, to Malats!’

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler, 1910

Pablo Picasso, Seated Nude, 1909

Although less well known than the others, the fourth volume can be heard as a vast coda to the collection, transporting us without a break from the verve of Lavapiés to the crepuscular magic and wholly oriental seductiveness of music which, in spite of its malaguena and sevillana rhythms (in Malaga and Eritaña respectively), is emphatically Moorish in its inflexions. The piano writing in all three pieces, even more dense than anything heard hitherto, pays ultimate tribute to the clavecinistes with its profusion of mordants and acciaccaturas. Jerez is a vast nocturne that revels in its own modality (it is written in the Hypodorian mode), dying away in a silence scarcely disturbed by the final outburst of Eritaña. As such, it performs the same central and determinative function as Almeria had done in the second book. Eritaña, the third of the three pieces celebrating Seville (the other two are El Corpus and Triana, of which Eritaña could be regarded as an extension), ends on a fortissimo that is suspensive rather than conclusive, as though the composer wanted to leave himself the option of writing a possible sequel or of returning to the beginning, since the cycle ends on the dominant of the opening key.

The present recording was made on the basis of the composer’s autograph scores, which are a veritable treasure-trove of information in several different ways. Albéniz’s extremely clear calligraphy bears admirable witness to his perpetual concern for lucid polyphonic textures. Evidently terrified by the complexity of the work, publishers of the period not only introduced a number of errors into the score but removed several characteristic instructions, many of which are full of lively imagery or striking in their own right. They also deleted or ‘adapted’ many of the phrasings, accents and dynamic markings so necessary to the balance of the work.

Pablo Picasso, Bust of a Woman, 1910

Georges Braque, Girl with a Cross, 1911-12

I am grateful, therefore, to the librarians of the Orfeó Catalá, the Biblioteca de Cataluña and the Museo de Música in Barcelona and to Peter Fay of the Library of Congress, Washington, DC, for their invaluable help in allowing me access to Albéniz’s original manuscripts.

ON ‘IBERIA’

Walter Aaron Clark

From Walter Aaron Clark’s review of a book on Iberia in Notes, Vol. 56 No. 4 (June 2000). Available in full from JSTOR.

Iberia is the most important collection of keyboard works written by a Spanish composer in the modern era. In the opinion of Olivier Messiaen, it even ranks in the highest category of works for the piano, period. Iberia represents the ultimate manifestation of Albéniz’s injunction that Spanish composers should ‘make Spanish music with a universal accent’. In Iberia we find a beguiling mélange of folkloric references, elements of French Impressionism, and post-Lisztian virtuosity blended together by a master hand.

The twelve pieces that make up the collection continue to astonish us with their kaleidoscopic variety, dazzling pyrotechnics, brilliant palette of color, and wide range of emotion, from profound despair to an almost giddy happiness. Here is a celebration not only of españolismo, but of human life itself. Albéniz was one of those Spanish artists, like Diego Velazquez, who focused so intently on the typical and characteristic that he succeeded in creating something that transcends the limitations of time and space.

Albéniz (1860-1909) was among the pre-eminent pianists of the nineteenth century, a child prodigy who began concertizing at age four and who by his teens was celebrated throughout Spain as a ‘phenomenon’ and a ‘national glory.’ Though the composer emerged from the virtuoso only gradually, by his late twenties Albéniz had produced a sizeable body of works for piano, including salon-style character pieces, sonatas, and—most important—numerous pianistic miniatures redolent of Spanish folk music, particularly of Andalusia. Here was his true calling, the one that would establish his reputation for posterity. During Albéniz’s third decade, however, his career took a new turn. Albéniz departed Spain first for London and then for Paris, where he resided from 1894 until his death. During the 1890s, he devoted his considerable energies to writing mostly for the theater: operas, operettas, and a zarzuela. Though these works have not held a place on the stage, they corresponded with a growing technical acumen, breadth, and command of compositional resources.

Toward the end of this decade, Albéniz resumed composing for the piano in a way that revealed for the first time the combination of these new resources with his nationalist orientation, and especially the influence of his Parisian surroundings and the Impressionist manner of Claude Debussy. Two works, Espagne: Souvenirs and ‘La vega’ (the only completed number from The Alhambra: Suite pour le piano) are clear harbingers of Iberia’s magnificence.

The four ‘books’ of Iberia, each containing three works, were composed between the years 1905 and 1908. Though Blanche Selva (1884-1942) premiered the complete books in France, in fact Albéniz wrote the works with his countryman Malats (1872-1912) in mind, and it was this pianist who first brought Iberia to the attention of the Spanish public. Sadly, Albéniz did not live long enough to see Iberia attain the lofty status it was soon to enjoy. He died from kidney failure only eleven days before his forty-ninth birthday and a little over a year after finishing his masterpiece.

As Jacinto Torres, the leading Spanish authority on Albéniz, puts it in his essay on the composer, ‘Albéniz felt and wrote Iberia from the distance of exile, from nostalgia for his land, from a burning anxiety tragically marked by the physical suffering (caused by kidney disease) and by the spiritual distress of an agnostic spirit which has a presentiment of the end of the road’.

The actual titles of the pieces are a source of some confusion. The first number, ‘Evocación,’ for example, appears as such only in the printed edition. In the manuscript it is titled ‘Prélude.’ Albéniz’s last-minute change was a felicitous one and much better describes the hazy, nostalgic character of this piece. What these titles actually tell us about the folkloric points of reference in each number is not often so clear. Torres offers a helpfully cautionary note on this subject: ‘The music of Albéniz is by no means lacking here and there in themes coming from a folkloric tradition, which can be easily traced and recognized, but—most of the time—what his music offers is an original output, a personal vision emanating from a deep stylization of a specific model’.

Albéniz’s exploitation of the fullest possible resources of the piano has inspired many to arrange Iberia for orchestra. The first attempt was made by Albéniz himself, who was unsatisfied with his rendition of ‘El puerto’ and left the job for his friend Enrique Fernandez Arbós (1863-1939), the famous violinist and conductor, and a composer in his own right. Arbós did not, however, orchestrate the entire collection, and Carlos Surinach provided complementary arrangements that round out the work.

Torres debunks Manuel do Falla’s mistaken assertion that Albéniz’s Iberia was inspired by Debussy’s eponymous work. Albéniz evidently planned to compose further Iberia books, but the sands of his life ran out too soon. Yet, Iberia gained additional stature by exerting a pronounced influence on Albéniz’s contemporaries and successors. Torres rightly concludes that Falla’s Fantasia bética of 1919 ‘would simply he unthinkable without the distinguished precedent of Iberia’.

ALBENIZ’S ‘IBERIA’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 7

̶ Ingrid, do you know Albeniz’s Iberia?

̶ Of course. It was thanks to ‘Corpus en Sevilla’ that I won my first piano competition.

̶ Would you play me ‘Evocación’?

̶ With pleasure!

As she slips her foot into her shoe the fall of her hair frees my emotion: I feel how we are bonded through you. She takes her place at the piano; I seat myself on the rug.

It comes, the melody; within the narrow compass of an octave it circles, encircling me in its delicate nostalgia. This is the sound of souls touching, this is silence speaking. I lie back on the rug and listen. What does the music say? It says that in loving you, Ingrid has touched me; it says that in loving you, I have moved her: The touch of her fingers on the keys is your touch reaching the core of us. Listen, she still loves you: That syncopation is your sly smile; that offbeat quality, your gangling gait… Words fall away, the music washes over me… Silence…

TWO VIDEO PERFORMANCES BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS HEISSER

Jean-François Heisser plays ‘Triana’ from Albéniz’s Iberia

Jean-François Heisser plays the last two pieces from Federico’s Mompou’s Música callada

GRANADOS, FALLA, ALBÉNIZ: THREE ALBUMS BY JEAN-FRANÇOIS HEISSER

Jean-François Heisser, Granados-Danzas Esp’s, 1992

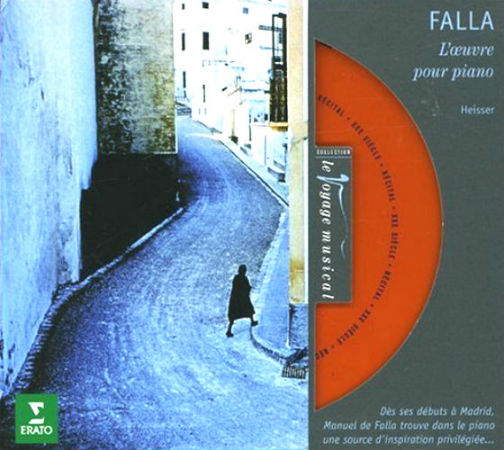

Jean-François Heisser, Falla : Piano Works, 1990

Jean-François Heisser, Albeniz-Iberia, 1994