Ysaÿe

EUGÈNE YSAŸE: SIX SONATAS FOR SOLO VIOLIN, Op. 27

Alone: Paul Griffiths on Ysaÿe, Sonatas for Solo Violin | Thomas Zehetmair, violin

This essay constitutes the liner notes to the album Eugène Ysaÿe, Sonates pour violon solo, op. 27 – Thomas Zehetmair, violin (ECM New Series no 1835, 2004).

This is a special occasion. The violin, which is used to hearing from other instruments below the middle-register G that is its fixed lower boundary, is by itself. The violinist, normally a partner or a star in collectivities, is alone. But wait. To see this as unusual is to look at the case from our viewpoint, as listeners. For the violinist, solitariness is the common condition. The violinist spends a lot of time alone, practicing. The violinist, as a virtuoso, must also be a recluse. Perhaps it follows that music for violin alone is most likely to come from composers sharing that experience—fellow violinists—who will put into their music memories of the practice room. This will be music rooted in exercises: flickering arpeggios and scale fragments, quick changes of bowing, testings of different colours, challenges to phrasing and agility. It will be music where virtuosity is spurred not so much by an audience as by the instrument—its technical possibilities, its history, its whole culture—and by the violinist’s mechanisms of self-proving.

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

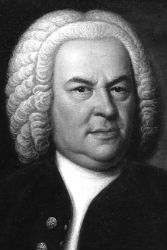

Music that conveys this texture of study and yet finds space for other ears—listeners’—is rare. The masterpieces here have their own loneliness: before Ysaÿe they are limited to the three sonatas and three partitas of Bach and the twenty-four caprices by Paganini. These works are on Ysaÿe’s mind as he writes his six sonatas at his home in the Belgian coastal resort of Het Zoute in 1923/24. They are under the fingers of his mind. He is alone but not alone. There are ghosts in the room.

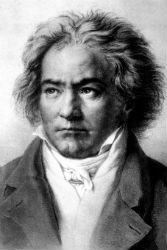

At this point, in his mid-sixties, he can survey a passionate affair with the violin that started when he was four. His father, a violinist and theatre conductor in Liège, had been his first teacher. Later he had studied with Wieniawski in Brussels and Vieuxtemps in Paris. By his mid-twenties he was acknowledged the outstanding virtuoso of his generation, with an unusual (for a virtuoso at that time) insistence on music of substance. His programmes were built from sonatas; he founded a quartet (1886), and made his sensational U.S. debut (1893) in the Beethoven concerto. Composers loved him. Works had come from his fellow Belgian Franck (the sonata as a wedding present), from Chausson (the Poème, the Concert), from Debussy (a quartet). He himself had written eight concertos, besides much else for his instrument. More present as he writes than all these personal memories, though, are those guiding and goading spirits, Bach and Paganini. So too for the violinist who retraces these supremely arduous, various and abundant journeys.

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

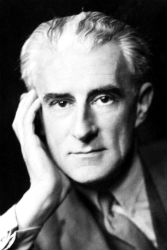

Playing Ysaÿe, the violinist will be revisiting his own memories and making his own discoveries. He too is continuing, through this hour or so, a path going back decades, to when he was a boy studying with his father. Born in Salzburg in 1961, he was trained in the Mozarteum and in master classes with Max Rostal and Nathan Milstein. In 1979 he made his debut, at the Musikverein in Vienna, and published his first recording. Like Ysaÿe a century before, he established himself as a musician with a personal vision and an inquiring mind, a player of passion and accuracy, an inspiring quartet leader, a conductor who sparks musical excitement even when he is not simultaneously performing as concerto soloist, and a friend of composers (in his case including Holliger and Kurtág). All of this is here, at the point of the bow. He burns himself into the music and disappears.

The first piece is a shadow sonata after Bach’s first, in the same key of G minor (but turning to the relative major, B flat, for the tearoom-tinted third movement) and with something like the same slow-fast-slow-fast plan, where a fugato is in second place (only Ysaÿe’s is steadier in speed). Startling at this time of back-to-Bach neoclassicism—the time of Stravinsky’s Concerto for piano and winds and Schoenberg’s Piano Suite—is the lack of contention and anxiety. Bach is not being rediscovered. Bach was always here. For the modern player this presence of Bach adds to all the work’s other difficulties a virtuosity in time travel, since generally now Bach is considered to be decisively elsewhere, retrievable only by means of historically sanctioned approaches. How could Ysaÿe reach him without a Baroque bow? And how is the musician now to reach both him and Ysaÿe, understand Ysaÿe’s adoption of Bachian ornaments? What style of performance could be suitable for both the 1920s and the 1720s?

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

The violinist has to cultivate his own aloneness, shut out (or digest) all the advice and warnings in order to pursue his dialogue with the text, performing not as if in the twentieth century, the eighteenth or the twenty-first but in that never-now where music takes place. Hear him. Right at the beginning the four-note chords and the motivic insistence (on the rising minor second especially) place us not so much with Bach or Ysaÿe as with weight and the struggle for the next step. Towards the close of this movement the shadow sonata includes its own shadow in a passage played sul ponticello, near the bridge. And then there are the endings, the points achieved: a chime of distant light; a wild high minor tenth, like a scream; the same interval softened and put into the major; the inevitable and decisive fifth.

In the second sonata (originally fourth: the composer swapped these two pieces around before publishing the set) Bach is not shadowed but emphatically present. Ysaÿe’s ‘Obsession’ is with music that is itself obsessive, the prelude from Bach’s E major partita, phrases from which are answered, diverted, echoed and developed in an A minor context. But the music is obsessed also with the Dies irae melody, which appears in all four movements. ‘Malinconia’, the E minor (or Phrygian) slow movement played with a mute, slips easily at the end from a gentle folksong atmosphere into the chant theme. The ‘Danse des Ombres’ (Dance of the Shades), in G, converts the plainsong first into a pizzicato sarabande and then, in six variations, into further avatars—another folksong, a musette, a two-part invention in the minor, and so on—before ending with the sarabande again, now bowed. Finally, ‘Les Furies’ restores the force and temper of the first movement, and eventually the A minor tonality. In another composer the extremes of rage in this sonata might seem directed at the great predecessor who is being quoted—or at his absence. Ysaÿe, however, is with Bach. The quotations are gradually integrated, and meaningful here in the way they were in the Bach partita. Bach, folk music, gypsy fiddling—all are near at hand. The violinist is alone, certainly, but at the same time everywhere in the world of the violin.

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

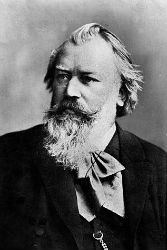

The third sonata is a single movement, whose title, ‘Ballade’, suitably suggests a Chopin-like or Brahmsian combination of virtuosity and narrative thrust. Accordingly the main body of the movement, in D minor, is a chain of extensions from an assertive theme in proud dotted rhythm. Such passionate music could not just start up out of nowhere; it has to be preceded by an introduction (a gearing-up largely in double stops) and what one might call a pre-introduction, ‘in modo di recitativo’, slow and featuring a drift of chromatic melody.

With the fourth sonata Ysaÿe returns closer to the Bach model—explicitly to the model of the partitas. As in both the B minor partita and the D minor, the opening movement is an allemande–at least ostensibly, for this one switches from the quadruple time characteristic of the Bachian allemande to triple after its introduction. Jumping over the customary courante, Ysaÿe arrives at another slow dance, the sarabande, for his second movement, authentically couched in triple time and sporting a concealed ostinato: a descending scale fragment A-G-F-E recurring every bar. The finale, a perpetuum mobile, brings back the allemande for its middle section, being otherwise somewhat gigue-like. Recalling that this sonata was originally the second, one wonders if the composer’s initial plan was for an alternation between sonatas and partitas, as in the Bach collection. All three movements are in E minor, the finale moving into the major as it catches sight of its end.

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Different again, the fifth sonata, in G major, is an essay in the picturesque. The first movement, ‘L’Aurore’ (The Dawn), achieves an impression of sunrise in its opening two slow phrases, lifting from the open fifth at the bottom of the instrument’s range, G-D. Following this, the image is created again much more expansively. The pure diatonic ascent of the initial segment now, on repetition, falls to a harsh dissonance, and this idea—D-E-B-F, later widened to D-G-E-B flat—is developed, rising in register and regaining harmonic clarity to end with dazzling arpeggios. The same idea is then the seed for a ‘Danse rustique’, the motif appearing in all the movement’s several phases.

Ysaÿe, perhaps imagining performances of the sonatas as a programme, made sure the last would be a fit finale. At one point entitled ‘Fantaisie’, it might be described as a cadenza with habanera, in E major, the Hispanic tone suiting the dedicatee, Manuel Quiroga, the greatest Spanish violinist of his time. Each of the other sonatas is similarly dedicated to a younger colleague, whose personality and repertory are reflected in the music: the first to Joseph Szigeti, whose performances of the Bach solo pieces are said to have moved Ysaÿe to begin this set, and the middle four in order to Jacques Thibaud, George Enescu, Fritz Kreisler and Mathieu Crickboom (the composer’s compatriot, pupil and quartet partner).

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

Photo (detail): Deborah Turbeville

The master of them all, reflecting on a life with the violin that is almost over, conveys what he has learned. There is sagacity here, and rich experience. But what he writes is—in each note, each ornament, each double stop, each feathery flurry of sixths—a prompt for action. The violinist looks at the script. He has his own ghosts in the room with him, and they surely include Ysaÿe alongside Bach and Paganini. He lifts his bow. He acts.

SPOTIFY: EUGÈNE YSAŸE, SONATES POUR VIOLON SOLO – THOMAS ZEHETMAIR

Eugène Ysaÿe: Sonates pour violon solo | Thomas Zehetmair

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUM IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

THREE BOOKS BY PAUL GRIFFITHS

VIDEO: HILARY HAHN PLAYS EUGÈNE YSAŸE – SONATA NO. 2 IN A MINOR

Hilary Hahn plays Ysaÿe’s Sonata No 2, ‘Obsession’ & ‘Malinconia’

Hilary Hahn plays Ysaÿe’s Sonata No 2, ‘Danse des ombres’ & ‘Les furies’

EUGÈNE YSAŸE IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 6

What is certain, however, is that at that moment, you hated your body and wanted to put an end to your life. Why didn’t you? Was it because you couldn’t resolve the paradox of wanting to kill yourself not in order to die, but rather to find a better way to live? Did your fantasy of death as a return to the womb, enabling you to be born again in a new skin, evaporate in the light of reason? Or did salvation come, when all is said and done, through your violin? Indeed, as your teacher reported, from Paganini’s Caprices you extracted the music their role as virtuoso exercises had hidden: You brought out more musicality than she had heard in many a year. And then you immersed yourself in another masterwork for the unaccompanied instrument: Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin. Alone in your room in Neuchâtel, savage in your solitude, you entered a forest of notes where nothing but the possibilities of the instrument itself, informed by the ghosts of its culture, spurred the virtuosity of the music. Confronting the composer, encountering yourself, from your fierce isolation you drew dark meditations, daring and disturbing. And thus into being you brought the music’s power and beauty, and thus you expressed your passion and soothed your soul.

Woestyne, Adrienne with a Violin, 1920

Duncan Grant, Angelica Playing the Violin, 1934

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Five Chapter 15

In your studio on the leafy rue Colbert, upon an evening, you’d continue to pursue the ghosts of Bach and Paganini in Ysaÿe’s Six Sonatas for Solo Violin. Despite your familiarity with the pieces, you often found yourself having to pause and lie on your bed, overcome by the beauty of the music, its inexhaustible depth and boldness of invention. At such moments you’d feel yourself vast, as vast as the ocean that envelopes the earth, and as undifferentiated. And yet, at the same time, you’d feel with redoubled intensity that pulse in your blood that you know to be your individuality. And thus it was that your violin would simultaneously put you in touch with yourself and make you untouchable.

Making love in such a state was magical: Supple, responsive, never making a wrong move, you, Inès found, were an inspired lover.

Colin Campbell Cooper, Two Women, 1917-18

Frank Desch, Two Women Having Tea, n.d.

For your part, you found thrilling her mix of sensitivity, skill and ability to surprise.