Bartók

Romanian Dances

BELA BARTOK: FOLK MUSIC AND THE REFLECTION OF SPIRIT AND EMOTION

The Formation of Bartok’s Aesthetics

By Judit Frigyesi

From Judit Frigyesi, Béla Bartόk and Turn-of-the-Century Budapest (University of California Press, 1998) pp. 119-123

Twentieth-century textbooks use various terms to describe the distinctive cultural traits that shaped Bartok’s art. They call him a ‘folklorist’ or an ‘almost serialist’ composer and place him under the rubric ‘East European School,’ ‘Nationalist Composition,’ or ‘Independent Trends.’ Most such characterizations are appropriate in one context or another. Bartok’s artistic decisions were obviously the result of a common historical and cultural tradition, and the stylistic traits of his art naturally show similarities to other modernist developments. Yet none suggests the essential feature of Bartok’s aesthetics: a highly individual choice of elements from the common stylistic-aesthetic tradition and their articulation in a coherent personal style. The particular blend of modernist tendencies and his unique manner of interpreting them for his own purposes created an aesthetics that in its totality was without parallel even in Hungary.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Portrait of a Girl, n.d.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Country Girl, n.d.

Among the most important elements in the background of this aesthetics was a dual conception of the artwork’s ‘spirit.’ As Bartok understood it, the artwork was to express a communal spirit (the spirit of folk music) and yet arise from the inner urge of the artist to express his emotions. ‘Spirit’ was something beyond the material of music; in the case of folk music, it expressed the totality of lived experience. This attitude is best illustrated by the statement Bartok wrote in 1928:

It was of the utmost consequence to us that we had to do our collecting of folk songs ourselves, and did not make the acquaintance of our melodic material in written or printed collections. The melodies of a written or printed collection are in essence dead materials. It is true though—provided they are reliable—that they acquaint one with the melodies, yet one absolutely cannot penetrate into the real, throbbing life of this music by means of them. In order to really feel the vitality of this music, one must, so to speak, have lived it—and this is only possible when one comes to know it through direct contact with the peasants. I should, in fact, stress one point: in our case it was not a question of merely taking unique melodies in any way whatsoever, and then incorporating them—or fragments of them—in our works, there to develop them according to the traditionally established custom. This would have been mere craftsmanship, and could have led to no new and unified style. What we had to do was to grasp the spirit of this hitherto unknown music and to make this spirit (difficult to describe in words) the basis of our works.

Bartok’s commitment to expressing ‘the spirit’ of folk music is much more familiar to us than his individualistic approach toward art because he described the latter in letters mostly unavailable in English. In a letter to his wife during a field trip to Darázs (Slovakia) in 1909, he wrote:

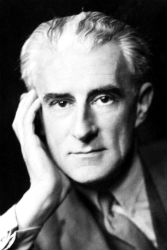

I strongly believe and profess that every true art is manifested and created under the influence of ‘experiences,’ those impressions that we absorb into ourselves from the surrounding world. He who paints only in order to paint a landscape or writes a symphony only in order to write one is no more than a good craftsman at best. I cannot imagine that an artwork could be anything but the manifestation of the infinite enthusiasm, despair, sorrow, vengeful anger, distorting and sarcastic irony of its creator. Before I experienced it in myself, I did not believe that one’s works could signal—more precisely than one’s autobiography—the important events, the governing passions of his life. Of course, I am talking here only of a real and true artist. It is strange that in music the basis of motivation has so far been only enthusiasm, love, sorrow, or, at most, despair—that is, only the so-called lofty feelings. It is only in our times that there is place for the painting of the feeling of vengeance, the grotesque, and the sarcastic. For this reason the music of today could be called realist because, unlike the idealism of the previous eras, it extends with honesty to all real human emotions without excluding any. In the last century, there were only sporadic examples for this, for instance, in Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, Liszt’s Faust, Wagner’s Meistersinger, and Strauss’s Heldenleben. There is another factor that makes today’s music real: that its impressions come, partly subconsciously and partly intentionally, from folk music, that is, a music that saturates everything in the great reality.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Peasant Woman, n.d.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Catinca, n.d.

In these writings Bartok makes two demands on art that seem at first glance contradictory. If the artwork expresses the spirit of folk music, how could it at the same time express the personal feelings of the artist? Yet it is clear that Bartok envisioned precisely such a synthesis. In his view, only by living up to this dual demand could the artwork be ‘true’ and ‘real.’ Realism, in Bartok’s conception, is not the imitation of empirical reality but ‘honesty’—what is true both to the grand totality of life and to the artist’s deepest feelings. Bartok envisioned an ideal connection between two realisms in art: the realism that means the artist’s truthfulness to his own infinite passion, and the realism that results from his capacity to relive, so to speak, the ‘great reality’ of life, remaining faithful to its basic and original manifestations—which is, musically speaking, folk music.

Bartok insisted on this synthesis throughout his career. The original plan of the Harvard lectures from 1943, the last attempt to summarize his style and artistic belief, restates the aesthetics that he explained in the letter from 1909. In summarizing the structure and character of his music, Bartok planned to discuss nine topics (in order): 1. revolution, evolution; 2. modes, polymodality (polytonality, atonality/twelve-tone music); 3 chromaticism (very rare in folk music); 4. rhythm, percussion effects; 5. form (every piece creates its own form); 6. scoring (new effects on instruments), piano, violin as percussive; 7. trend toward simplicity; 8. educational works; 9. general spirit (connected with folk music).

Nicolae Grigorescu, Portrait of a Little Peasant Girl, n.d.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Portrait of a Girl, n.d.

Because of his illness, Bartok had to interrupt the lecture series after the third lecture. By that time he had written part of the fourth lecture and an autograph draft containing the above outline, but nothing survived of lectures five through nine. Thus the Harvard lectures as we know them today give the impression that Bartok attempted a purely technical analysis of his style. As this draft illustrates, his intention was different: he planned to progress from structural aspects (outlining even their relation to originality and folk music) toward aesthetic issues and hoped to end the series, in a final message, with the discussion of the ‘general spirit (connected with folk music).’ Since Bartok had great difficulty verbalizing anything that was not purely technical, it is remarkable that he considered devoting a full lecture to the issue of simplicity and another to ‘spirit.’ The inclusion of educational works is also significant. First, it indicates his emphasis on the social aspect of art music, his belief that the composer had to find channels through which he could reconnect his art to a broader community. Second, with the emphasis on separating the topic of educational pieces from ‘simplicity,’ he apparently wanted to emphasize that, in his understanding, ‘simplicity’ meant something other than easily accessible or popular. Most important, the lecture series concludes with the same idea he had expressed years earlier: the title ‘general spirit (connected with folk music)’ reaffirms the dual demand of spirit on the artwork.

But how could the spirit of folk music manifest itself in a composition that is no longer folk music? Only at the beginning of his career did Bartok view folk song as a self-contained entity and a representative type that could evoke, at least symbolically, folk music. Later he came to the realization that spirit cannot be connected in any direct manner to technical aspects of the music. This realization came gradually, and the process of distancing the thematic material of the original compositions from the actual appearance of their folk-music models was by no means absolute. While the sources of Bartok’s compositions became gradually more abstract than an actual piece or type, some works reiterated obvious surface features of the folk song. Yet typically, at least in the mature compositions, his point of departure was not an actual piece or type but a complex web of dissociated musical elements, variational procedures, and other structural ideas. He treated the dissociated elements of folk music, together with elements of art music, as a collection of rough material that he could draw on as he wished, to create his style.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Head of a Girl, n.d.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Peasant Girl, n.d.

The accent here is on the separation and reconnection of spirit and material. Elements of folk music permeate the composition but no longer appear in the surface form. Yet the composition retains the feeling of folk music and even intensifies it, filtering it through a personal interpretation. Moreover, the complex design of the large-scale form conveys this spirit, even though its dimensions are incongruous with the conciseness of folk music.

Bartok’s mature compositions have great variety of structural designs and yet share a certain orientation. All the mature pieces achieve maximum integrity in the thematic material and create, at the same time, the maximum polarization of thematic characters. During the process of thematic-motivic transformations, themes of similar-sounding materials diverge while ones that began by sounding different merge. No parts of the music, not even those themes that sound somewhat like folk songs, have direct connections to any particular piece or type of the actual folk-song repertoire.

Nicolae Grigorescu, Peasant Girl, n.d.

BELA BARTOK: THREE BOOKS

Claire Delamarche, Bela Bartok (in French)

VIDEO: BELA BARTOK, ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES

Tessa Lark, violin & Yannick Rafalimanana, piano

Oláh Dezsö Trio: Reflection of Béla Bartók’s Six Romanian Folk Dances

SPOTIFY: BELA BARTOK, ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES

Kurt Nikkanen

Deutsche Streicherphilharmonie

Oláh Dezsö Triό, Reflections-Bartόk

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

BARTOK’S ‘ROMANIAN DANCES’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 3

So this is Bartók’s distillation of village ritual, this is ‘Fast Steps’: I delight in your rhythmic élan and the sight of your body swaying; as your legs push up from the floor, I imagine you on your back in a barn. Matteo drives the dance forward; a final flourish, then it’s done. As the applause erupts I realize that in barely five minutes you’ve drawn from your violin centuries of tradition: Nourished by a millennial culture, Bartók’s roots run deep.

Helvetians, Gauls and Romans,

Vandals and Franks,

Conspired to create you, Marietta.

Your roots run deep,

Very deep: Have I any chance

Of sweeping you off your feet?

I have no roots,

I am a nomad; my genealogy

Is a mystery to me.

But watch out, woman!

Home is where the heart is,

And my heart is set on you!

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Peasant Dance, 1567