Kodály

ZOLTÁN KODÁLY: MUSIC FOR CELLO, PART ONE

Three Chorale Preludes | Sonata for Solo Cello, Op. 8 | Sonata for Cello and Piano, Op. 4

By Ates Orga

The following text constitutes the liner notes to the album Kodaly: Music for Cello (Naxos 8.553160)

Kodály’s unhappy lot in life and history was to play second fiddle to Béla Bartók. For years he was accused of plagiarism, he was critically hounded (‘organised persecution’, Bartók called it), and his inherent gentleness and selfless personal demeanour was mistaken for weakness or lack of fibre. Given his lyric temperament, his nationalism, the premium he placed on expressive nuance and harmony, his misfortune perhaps was to have been born into an age progressively more interested in cancelling than renewing old values. He may have spanned the generations from old Liszt to young Ligeti, he may have lived through two world wars, Hitler, the Soviets and 1956, but comparatively little of such transition or trauma found reflection in his work. ‘For some time past,’ Bartók felt impelled to write in February 1921, ‘certain musical circles have made it their special concern to play me off against Zoltán Kodály. They would like to make it appear that the friendship between us is being used by Kodály for his own profit. This is a most stupid lie. Kodály is one of the most outstanding composers of our day. His art, like mine, has twin roots: it has sprung from Hungarian peasant soil and modern French music [Debussy].

János Vaszary, Portrait of a Lady, 1930-39

János Vaszary, The Morphinist, 1930

But though our art has grown from this common soil, our works from the very beginning have been completely different. It is possible that Kodály’s music is not so ‘aggressive’ [as mine]; it is possible that in form it is closer to certain traditions; it is also possible that it expresses calm meditation rather than ‘unbridled orgies’. But it is precisely this essential difference, reaching expression in his music as a completely new and original way of thinking, that makes his musical message so valuable. This man, to whom Hungarian culture owes so much, is attacked at every turn, sometimes by official circles, sometimes by ‘critics’. They are determined to prevent him from being able to work in peace for the good of our culture, and they do so while they, the incompetent, the idle and the nobodies, are proclaiming at the top of their voices the importance of maintaining the superiority of Hungarian culture’. Eventually Kodály was to be feted and honoured by the world—but it needed Bartók’s defence, a contract from Universal in Vienna (the publishers of Mahler, Strauss and Schoenberg), the international success of Psalmus Hungaricus and Háry János, and the weighty independent support of men like Toscanini, Furtwängler and Ansermet to stem the once oceanic flood of ill feeling against him.

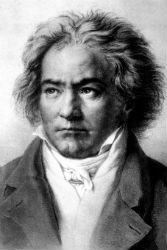

Kodály shared Beethoven’s birthday—16th December. As an old man (in 1966) he remembered himself as a village lowlander: ‘the Galanta district, where I began to find myself, is just as open as the Great Plain itself. But there was always a longing for mountains in me. From Galanta I could see the Carpathians looming blue in the distance, from Nagyszombat they were a little nearer, but it was years later before I could actually set foot on them’. ‘The shaping of my life,’ he wrote in 1950, ‘was as natural as breathing itself. I sang before I could speak, and I sang more than I spoke. I made my first instrument myself. I was hardly four years old when I took mother’s draining-ladle, threaded strings into its holes and fastened them to the end of the ladle. On these strings I played the guitar and sang improvised songs to this accompaniment’. In 1900 he went to Budapest, to read German and Hungarian at the University and to study at the Academy of Music with Reger’s cousin, Hans Koessler, the teacher of Bartók and Dohnanyi. His passions, composition apart, were collecting folk music (from 1905) and teaching (from 1907). With Bartók he was one of the great early ethnomusicologists of the century, notating, recording, documenting and publishing the living folk literature of his people fresh from the field. ‘Like their language, the music of the Hungarians is terse and lapidary, forming masterpieces that are small but weighty. Some tunes of a few notes have withstood the tempests of centuries’, ‘there is no fertile soil without traditions but traditions in themselves do not create higher forms of art’ (1939), were two among his many aphoristic perceptions. He was elected president of the International Folk Music Council in 1961.

János Vaszary, Woman in Profile with Black Turban, n.d.

János Vaszary, Woman with Black Hat, 1894

Originally in three movements, the Op. 4 Sonata was premièred by Jeno Kerpely and Bartók in Budapest, 17th March 1910. Growing out of the same elemental ‘old Hungarian’ intervals that a few years later were to lend wing to Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony, the opening F sharp minor Fantasia—an artful blend of rubato recitative, folk innuendo (the piano references, alla Liszt, to undamped cimbalom sound) and Debussyian harmonies—epitomises Bartók’s view of Kodály as a composer of ‘rich melodic invention, and a perfect sense of form, with a certain predilection for melancholy and uncertainty, and striving for inner contemplation’ (July 1921). Kodály claimed Beethoven to have inspired the stamping main theme of the second movement, but in its short-winded modal phrases, drone inflections and Háry János-like allusions, it’s nearer perhaps to peasant dance. The return of the Fantasia at the end (the final cello F sharp cutting through the piano’s distinctive G major triadic spacing) establishes a neat cyclic unity.

Dedicated to Kerpely and first played by him in Budapest on 7th May 1918, the Op. 8 Sonata, admired by Bartók for its ‘unusual and original style and surprising vocal effects’, is an extraordinary tour de force, not so much a reply to unaccompanied Bach as a visionary credo in pursuit of the ultimate, regardless of medium or technical limitation. In seeking his (B minor/major) goal, Kodály even has the lower two strings tuned down a semitone from normal (giving the configuration B-F sharp-D-A), notating them further as a transposing part. Inwardly, the three movements are tightly linked by recurring motifs and intervals. Outwardly, however, the impression is more random, a pageant of rhapsody and change, of sudden contrasts and pensive reflections, all exquisitely detailed in rhythm, phrasing, inflection and dynamics. Epic counterpoint and arresting gesture, recitatives, songs and dances, drones, shepherd pipes, zithers and cimbaloms, veritably a whole gypsy orchestra, make up Kodály’s vibrant dreamland. As monumental for cellists as the Liszt Sonata is for pianists, no more challenging a work exists. Kodály was never again to tackle the form.

The Three Chorale Preludes are arrangements of organ settings formerly attributed to Bach (BWV 743, 762, 747) but in fact spurious.

János Vaszary, The Artist’s Wife, n.d.

ZOLTÁN KODÁLY: MUSIC FOR CELLO, PART TWO

Prelude and Fugue | Sonatina for Cello and Piano | Adagio for Cello and Piano | Capriccio for Solo Cello | Hungarian Rondo for Cello and Piano | Duo for Violin and Cello, Op.7

By Keith Anderson

The following text constitutes the liner notes to the album Kodály: Music for Cello, Vol. II (Naxos 8.554039)

Jakob Bogdány, A Bouquet of Flowers, 1695

The son of a railway booking-clerk, Zoltán Kodály was born in 1882 at Kecskemét, fifty miles south-east of Budapest. In 1900, after a childhood largely spent in the Hungarian countryside, Kodály entered the Pazmany University in Budapest, studying German and Hungarian. At the same time he took lessons at the Academy of Music, where his composition teacher was Hans Koessler, a cousin of Max Reger, a musician for whom traditional Hungarian folk-song had no place. However, Kodály’s doctoral thesis in 1906 was devoted to just this subject, in the collection and investigation of which he had already busied himself, together with his close contemporary Béla Bartók.

After a brief period of study in Berlin, Kodály returned to Hungary to join the staff of the Academy where, in 1908, he took over the first-year composition class. In the following years he continued his activities as a composer and as a collector of folk-song, finding in the second activity a necessary foundation for art music that was genuinely Hungarian rather than in the conventional German mould. He became deputy director of the Academy, which was granted the status of a university in the short-lived Hungarian Republic established in 1919, but he was barred for a time from teaching after the fall of the Republic four months later and the accession to power of Admiral Horthy.

Jakob Bogdány, Peaches, Plums and Flowers, n.d.

Jakob Bogdány, Flowers in a Glass Bowl, 1690

Kodály’s music attracted increasing international attention in the following years, particularly with the first performance outside Hungary of his Psalmus Hungaricus in 1926 and the success of excerpts from his essentially Hungarian Singspiel Háry János. When he resumed his duties as a teacher, he was able to exert a strong influence on younger composers and a still greater influence over the whole process of musical education in Hungary, with methods that have, however imperfectly, been much imitated elsewhere. The task he set himself was to establish a truly Hungarian musical tradition, to be absorbed, as it was in his own music, into a recognisably Hungarian form of art music. While Bartók, whose style as a composer was generally more astringent and more experimental than Kodály’s, took refuge abroad, Kodály remained in Hungary during Admiral Horthy’s period of rule, as he did under the new dispensation established in the years after the war, much honoured at home and abroad. He died in Budapest in 1967.

Kodály’s transcription for cello and piano of the Prelude and Fugue in E flat minor from the first book of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier was made in 1951 and dedicated to Pablo Casals, who had emerged from self-imposed silence in 1950 for the Bach bicentenary. Kodály offers the transcription to Casals ‘in grateful memory of his wonderful renderings.’ Transposed to the more convenient and, for the cello, more resonant key of D minor, the Prelude allows melodic interest to the cello, which, in the Fugue provides the third and fourth entries of the fugal subject.

Jakob Bogdány, Flowers in a Glass Jug, 1690

Jakob Bogdány, Floral Still Life, 1690 (detail)

The Sonatina for cello and piano was completed in 1922 and originally intended as an additional movement for the two-movement Sonata for cello and piano, Opus 4 of 1909. Kodály found, however, that his style had changed during the previous decade, making its inclusion in the earlier sonata inappropriate. Broadly symmetrical in structure, with varied and transposed earlier material returning in the second part of the movement, the work remains thoroughly Hungarian in its melodic contours.

Kodály’s moving Adagio for cello and piano, which also exists in versions for violin or viola, was written in 1905 and dedicated, on its subsequent publication, to the violinist Imre Waldbauer of the Waldbauer-Kerpely Quartet, an ensemble then of great importance in the encouragement and performance of contemporary Hungarian chamber music. It was to this quartet that Kodály dedicated his own second work in that form, while providing the cellist, Jeno Kerpely, with a cello sonata. Tripartite in structure, the first section, which frames a more overtly Hungarian central section, returns in a modified form, slowly and gently unwinding to provide a conclusion.

Jakob Bogdány, Flowers in a Sculpted Vase, n.d.

Jakob Bogdány, Flower Still Life, n.d.

The Capriccio for solo cello, written in 1915, makes greater technical demands on a performer. After a dramatic introduction it moves forward to a rapid passage of divided octaves, framing a further passage of more complex virtuoso display. The Capriccio ends with gently plucked chords, after an emphatic chordal flourish in a dramatic coda.

Two years later Kodály wrote his Hungarian Rondo, the title of the version for cello and piano of the work for chamber orchestra first performed in Vienna in 1918, under the title Old Hungarian Soldiers’ Songs. This is an apt enough description of the thematic basis of the work, with its first characteristic melody used to frame a series of episodes based on other traditional Hungarian material.

Jakob Bogdány, Flowers in a Stone Vase, n.d.

Jakob Bogdány, Flowers with Fruit, a Monkey and Birds, n.d.

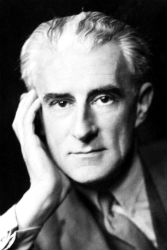

Written in 1914, the Duo for violin and cello, Opus 7 was first heard abroad at the ISCM festival of 1924 in Salzburg. The work maintains a perfect balance between the two instruments. There is something gently rhapsodic in the Hungarian contours of the opening, as the instruments take it in turns to accompany in plucked notes or to state the principal melody, developing into fiercer textures. There is an expressive second movement, thematically related to what has passed, leading to dramatic rhetoric, as the dialogue between the two instruments continues. The cadenza-like Maestoso e largamente, ma non troppo lento is followed by a rapid Presto that sometimes suggests in its sonorities the work of Ravel for violin and cello, before its final march to a brilliant conclusion.

ZOLTÁN KODÁLY: THE SPIRIT OF HUNGARY

From Joseph Machlis, Introduction to Contemporary Music, Second Edition (W.W. Norton & Co., 1979) pp. 314-16

‘If I were asked,’ Béla Bartók wrote, ‘in whose music the spirit of Hungary is most perfectly embodied, I would reply, in Kodály’s. His music is indeed a profession of faith in the spirit of Hungary. Objectively this may be explained by the fact that his work as a composer is entirely rooted in the soil of Hungarian folk music. Subjectively it is due to Kodály’s unwavering faith in the creative strength of his people and his confidence in their future.’

Simon Hantaï, Composition, 1956

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1957

For ten years, from 1906 on, Kodály and Bartók spent their summers together, traveling through the villages of their homeland with recording equipment and taking down the ancient melodies exactly as the peasants sang them. The two young composers, acutely aware that in musical matters Budapest had become a colony of Vienna and Berlin, perceived it as their lifework to create an autochthonous art based on authentically Hungarian materials. Armed with the energy of youth and the zeal of the missionary, they persisted despite the carping of critics and the indifference of the musical establishment. Fortunately, what they advocated made too much sense for it to be rejected indefinitely. After a time their ideas caught on.

History separated the two comrades-in-arms. As the regime of Admiral Horthy moved closer to Hitler, Bartók left for the United States. Kodály remained behind, his more adaptable nature choosing ‘internal emigration’—that is, an increasing aloofness from the Nazi tide and the expression of his antifascist sentiments in subtle ways: for example, his Variations for Orchestra on the patriotic song The Peacock, his choral setting of which the authorities had already banned. When Hitler’s troops occupied Hungary in 1944, Kodály’ s situation became precarious, for his wife was Jewish. They found refuge in the air-raid shelter of a convent, where Kodály completed a chorus for women’s voices, For St. Agnes’s Day, dedicated to the Mother Superior who had been instrumental in saving their lives.

Simon Hantaï, Untitled, 1957

Simon Hantaï, Composition, 1957

Kodály’s enormous impact on the artistic life of his homeland was the result of his functioning as a total musician: composer, ethnomusicologist—that is, scholar and scientific folklorist—critic, educator, and organizer of musical events and institutions. Each of these activities was related to the rest, and together they represented a total commitment to the ideal of freeing Hungarian music from German domination through the spirit of its folklore. From his absorption in the Hungarian folk idiom he distilled a musical language all his own. His melodies are often pentatonic or minor, with sparing use of chromatic inflection. They seem to have been made up on the spur of the moment. This improvisational quality manifests itself in extravagant flourishes, of a kind that are deeply embedded in Hungarian music. Typical are the abrupt changes of tempo, sudden shifts in mood, and a fondness for repetitive patterns based on simple rhythms.

Colorful orchestration and infectious rhythms have established Kodály’s chief orchestral works in the international repertory. Chief among these are the Dances from Galanta (1933), Variations on ‘The Peacock’ (1939), and Concerto for Orchestra (1939). Among the important vocal works are the Psalmus hungaricus (1923) and Missa brevis (Short Mass, 1952). The most important of his works for the stage is Háry János, whose hero was well described by the composer: ‘Háry is a peasant, a veteran soldier, who day after day sits in the tavern, spinning yarns about his heroic exploits. Since he is a real peasant, the stories produced by his fantastic imagination are an inextricable mixture of realism and naiveté, of comic humor and pathos. That his stories are not true is irrelevant, for they are the fruit of a lively imagination, seeking to create for himself and for others a beautiful dreamworld.’ The work is best known through an orchestral suite that scored an international success.

Simon Hantaï, Peinture, 1956

Simon Hantaï, Sans titre, 1957

It was Kodály’s high achievement to achieve a fine synthesis of personal style and national expression. As a result, he spoke not only to his own people but to the world.

KODÁLY’S ‘ADAGIO FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 3

Slow across the string your bow travels, drawing out a long line with gravity and grace. Footfalls in a forest, the silent dark; a pool of water, a clearing: Matteo keeps pace, a discreet presence in a dim landscape. The quiet beauty of this dirge makes for a solemn encore. Does it mean you haven’t forgotten El Salvador, the woman mourning the girl she couldn’t be? Does it mean that even if you’re on top of the world, you know what it’s like to be on the bottom? Or does it simply mean you need to ease yourself down after the incredible high of Tzigane? The elegy unfolds, your hands serving your heart as you shape raw emotion into subtle shades of feeling. Sustaining the contours of the slow-moving lines, between pressure and speed, tension and release, your bow finds a balance that makes the music flow. And now Matteo sketches out a new motif, another consolation for loss. Your violin renews its plaintive search with greater intensity—but just what is it you are searching for?

Simon Hataï, Composition, 1957

Simon Hataï, Composition, n.d.

Over the terrain of the music your hand moves the bow, like a blind man his fingers over something unknown. And I, too, move like a blind man: Who are you, Marietta? The force and refinement, the power and delicacy, that I first sensed in you on that patio in Princeton didn’t prepare me for the intensity you’ve shown me tonight. God, what radiant musicality! What splendour! You inhabit music like a calligrapher a line, a hawk the wind, a dancer the dance. Is the ephemeral, then, an element in your ethics of living? Is living the moment all that matters? Or is it simply a question of grace? Hush! Arpeggiated chords glitter; sunlight streams into the forest. The music opens out and dilates, flowing forward in long, arching lines. Within each string your bow discovers nuances of colour; in the tiny space between fingerboard and bridge, it finds an infinity of tenderness. Over what void do you weave this fabric, from what dead do you withdraw your attachment? In a flourish you bring the poignancy to a higher pitch, and then at the place where the bow lives in the string you breathe with more abandon, and let the music dissolve into silence…

SPOTIFY: THREE KODÁLY CELLO ALBUMS

Kodály, Music for Cello, Vol. I

Tatjana Vassilieva, Solo Cello

Kodály, Music for Cello, Vol. II

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

VIDEO: KODÁLY, SONATA FOR SOLO CELLO, OPUS 8

I. Allegro maestoso ma appassionato | Tatjana Vassilieva

II. Adagio con gran espressione | János Starker

III. Allegro molto vivace | Tatjana Vassilieva

KODÁLY: TWO BOOKS AND AN ARTICLE

Kodály: Life in Pictures & Documents