ERNEST BLOCH

ERNEST BLOCH: AN OVERVIEW

The Hebraic Spirit and Personal Style

From Joseph Machlis, Introduction to Contemporary Music, Second Edition (W.W. Norton & Co., 1979) pp. 309-12

Ernest Bloch (1880-1959), who was born in Switzerland and settled in the United States when he was thirty-six, found his personal style through mystical identification with the Hebraic spirit. His response to his heritage was on the deepest psychic level. ‘It is the Jewish soul that interests me, the complex, glowing, agitated soul that I feel vibrating throughout the Bible: the freshness and naiveté of the Patriarchs, the violence of the books of the Prophets, the Jew’s savage love of justice, the despair of Ecclesiastes, the sorrow and immensity of the Book of Job, the sensuality of the Song of Songs. It is all this that I strive to hear in myself and to translate in my music—the sacred emotion of the race that slumbers deep in our soul.’

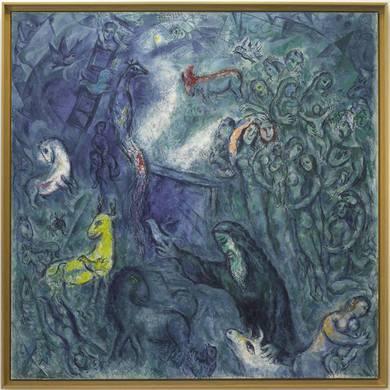

Marc Chagall, The Sacrifice of Isaac, 1960-66

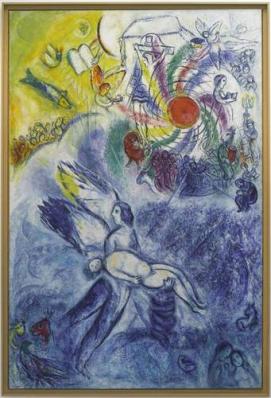

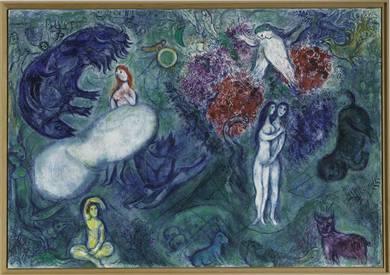

Chagall, Creation of Man, 1956-58

Given in equal degree to sensuous abandon and mystic exaltation, Bloch saw himself as a kind of messianic personality. Yet the biblical vision represented only one side of Bloch’s art. He was also a modern European and a sophisticate, a member of an uprooted generation in whom intellect warred with unruly emotion. Ultimately the inner struggle became greater than even so strong a personality could sustain. In his mid-fifties, when he should have been at the height of his powers (and when, ironically, he had achieved the leisure of which every artist dreams), there was a marked slackening of his creative energy. Bloch continued to work into his seventies. Yet with the exception of the Sacred Service (1933), the works on which his fame rests were almost all written between his thirtieth and forty-fifth years.

Bloch’s ‘Jewish Cycle’ includes his most widely played work, Schelomo (Solomon, 1916); the Israel Symphony (1912-1916); Trois Poèmes juifs (1913); Psalms 114 and 137 for soprano and orchestra, and Psalm 22 for baritone and orchestra (1914); Baal Shem, on Jewish legends, for violin and piano (1923, subsequently arranged for orchestra); and Voice in the Wilderness for cello and chamber orchestra (1936). Several of Bloch’s works lie outside the sphere of the specifically national.

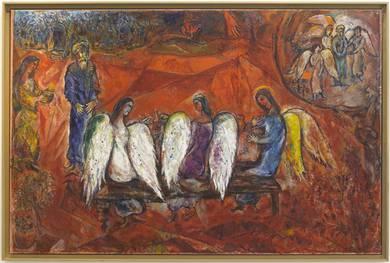

Marc Chagall, Abraham and the Three Angels, 1960-66

Marc Chagall, Adam and Eve Expelled from Paradise, 1961

The best known of these is the Concerto Grosso for strings with piano obbligato, which Bloch wrote in 1925 as a model for his students in the Neoclassic style. To this category belong also the noble Quintet for piano and strings (1923) and the String Quartets Nos. 1 (1916) and 2 (1946). In these non-programmatic compositions we see the tone poet refining the picturesque national elements in his idiom, sublimating them in order to achieve greater abstraction and universality of style.

In Schelomo (Solomon), a ‘Hebraic Rhapsody’ for cello and orchestra, Bloch evokes a biblical landscape now harsh and austere, now lush and opulent; an antique region wreathed in the splendor that attaches to a land one has never seen. This musical portrait of King Solomon is projected with all the exuberance of a temperament whose natural utterance inclined him to the impassioned and the grandiose.

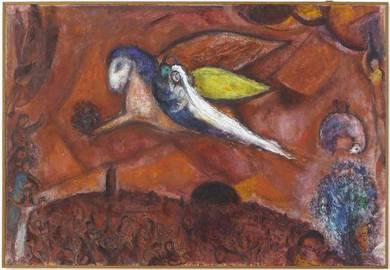

Marc Chagall, The Song of Songs IV, 1958

Marc Chagall, The Song of Songs V, 1965-66

The music conjures up the image of Solomon in all his glory—king and warrior, poet and lover, sage and prophet; the builder of the Temple, the sensualist of the Song of Songs, the keen wit of the Proverbs, finally the disenchanted Preacher proclaiming that all is vanity.

Bloch’s kind of music is not in fashion at the moment. But fashions change more quickly than we suspect. If he seems to be cut off from the mainstream of contemporary musical thought right now, it is quite likely that, as his distinguished pupil Roger Sessions prophesies, ‘the adjustments of history will restore to him his true place among the artists who have spoken most commandingly the language of conscious emotion.’

Marc Chagall, The Song of Songs I, 1960

ERNEST BLOCH: TWENTIETH–CENTURY MUSIC IMBUED WITH THE SPIRIT OF THE PAST

By Guido Fischer

The following text constitutes the liner notes to the album Ernest Bloch: Suites pour violoncelle, Emmanuelle Bertrand, cello & Pascal Amoyel, piano.

Marc Chagall, Noah’s Rainbow, 1961-66

There are labels and prejudices that last longer than an entire lifetime. In music too. As in the case of the Jewish composer Ernest Bloch (1880-1959), born a Swiss, American by choice, who is still considered the father of modern Jewish music. His best-known works are often adduced as evidence for this: the Hebrew Rhapsody Schelomo for cello and orchestra (1916), the Suite hébraïque for viola and orchestra (1951), or the Méditation hébraïque of 1924.

Yet the very titles of the works already indicate that ‘Hebrew music’ is not quite the same as ‘Jewish music’. For instead of copying the folk idioms of Eastern European Jewry using a classical vocabulary, Bloch sought for his purely expressive music a spiritual affinity with the traditional Hebrew liturgy and the Bible.

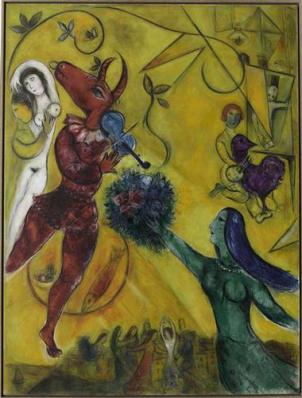

Marc Chagall, The Dance, 1950

Marc Chagall, Passover, 1968

‘It is neither my intention nor my wish to attempt a reconstruction of Jewish music’, Bloch once declared. ‘I am not an archaeologist; for me the important thing is to write good and sincere music. What interests me is the Jewish soul, the enigmatic ardent turbulent soul that I feel vibrating throughout the Bible; the freshness, the violence of the Prophetic Books, the sorrow and immense greatness of the book of Job; the sensuality of the Song of Songs. It is all this that I endeavour to hear in myself and to transcribe in my music. I have but listened to an inner voice, a voice that seemed to come from far beyond myself, which surged up in me on reading certain passages of the Bible.’

It was in fact seven years after the end of the composer’s ‘Jewish period’ (1912-1917), and in homage to Pablo Casals, that he wrote this Méditation hébraïque for cello and piano, which eloquently conveys Bloch’s spiritual intensity.

Marc Chagall, Jacob’s Dream, 1960-66

Marc Chagall, Song of Songs III, 1960

Composed in 1924, in Cleveland where the composer was Director of the Institute of Music from 1920 to 1925, this miniature in three sections (Moderato – Allegro deciso – Moderato) is a work of glowing melody and euphonious dignity; Bloch combines oriental colouring and quarter-tone writing with both rhythmic and metrical imitation of the Hebrew language.

But Bloch’s wide-ranging musical output was not solely focused on the invention of a rhapsodic language impregnated with religious faith. Again and again, in Bloch’s work, one detects attempts at making a fresh start, even though these are frequently based on existing models. His opera Macbeth (1904/09) is wholly under the sway of Claude Debussy, whom Bloch had got to know in Paris. In his final creative period, from 1944 until his death in 1959, Bloch experimented with the most diverse forms and techniques. Hence, in his Second and Third String Quartets, he falls back on dodecaphony in the style of Arnold Schoenberg.

Marc Chagall, Paradise, 1961

Marc Chagall, Song of Songs II, 1957

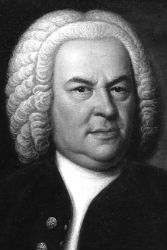

In the Concerto Grosso no.2 (1952), on the other hand, he resumes an earlier preoccupation with the European tradition: he had already made an intensive study of the art of counterpoint in the works of Palestrina, and especially of Johann Sebastian Bach, in the mid-1920s. The high points of this neoclassical interest in the past are undoubtedly the intimate chamber-like suites for solo string instrument (violin, viola, cello) that Bloch composed in the last three years of his life. The choice of the family of instruments for these works must have been almost a foregone conclusion. After all, Bloch had served an apprenticeship with the legendary violin virtuoso Eugène Ysaÿe in 1896. And later on, the cello became the preferred vehicle for his Hebrew-inspired sound-worlds.

The trilogy of suites for solo cello, composed in 1956-57, may be seen as a point of intersection between the heritage of Bach and the three cello suites of Benjamin Britten. Bloch sets structural throwbacks like the rhythmic figurations, which recall Baroque dance forms, against a chromatic language with a forceful mix of harmonic colours; the manifest reminiscence, in these suites, of the cantabile properties of the cello, the emotional impact of its sound, is quite unmistakably to be heard once more in the Britten works (1964-1971). And just as Britten’s ideal interpreter for these pieces was the masterly Russian performer Mstislav Rostropovich, so Bloch’s for his was the Canadian cellist Zara Nelsova.

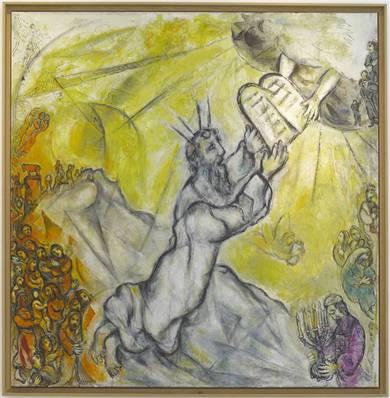

Marc Chagall, Crossing the Red Sea, 1955

Marc Chagall, Moses-Tables-Law, 1960-66

After they had recorded Schelomo together, Bloch said of her: ‘Zara Nelsova is my music.’ It was also at Nelsova’s prompting that Bloch composed the three cello suites, though only after a certain initial scepticism, as she later recalled: Once I asked him if he would write an unaccompanied cello sonata. ‘Oh’, he said, ‘I don’t know. How would I do that? Play me something.’ So I sat down and played him a little of the Kodaly solo sonata. ‘No, no, that’s not my style.’ Then I played some of the Reger Second Suite. ‘No, no, that’s not my style.’ Nothing would please him.

Then, during a European tour, Zara Nelsova was surprised to receive a letter informing her that he was working on an unaccompanied suite: He ended up sending me three suites, one at a time, the first two being dedicated to me. The third he meant to dedicate to me, but he sent it to me in Europe to edit and I didn’t get it in time. He didn’t hear from me so he assumed that I didn’t like it. The work remains undedicated. All three suites are very beautiful. Above all, the suites are, in their form and expression, a typical example of the characteristic relationship with the past of Bloch’s own creative and expressive powers.

Marc Chagall, Noah’s Ark, 1961-66

Marc Chagall, Jacob Wrestling – Angel, 1960-66

If the opening C-minor Prelude of the four-movement Suite no.1, in its Protestant seriousness, is still in effect close to Bach, in the Allegro a little cantilena is stretched out with virtuoso agility, and a melody of wonderful simplicity blossoms in the Canzona. The concluding Allegro, on the other hand, possesses a certain gravity, though its form as a gigue allows Bloch’s rhapsodic flair to triumph.

Suite no.2 is also built on the four-movement principle, but with an entirely different emphasis. After the harmonic friction of the Prelude and Allegro, the Andante tranquillo is melancholy and withdrawn in character, whilst the Allegro finale sweeps the listener along with its robust drama and almost excessive culminating moments. Bloch was in the habit of returning to the material of earlier movements, and this cyclical principle is the very essence of Suite no.3.

Marc Chagall, Splitting the Rock, 1960-66

Chagall, Moses Beholding the Burning Bush, 1960-66

But if the rhythmic terseness of the first movement (Allegro deciso) is mirrored in the finale (Allegro giocoso), Bloch suddenly finds in the middle movements an ascetic sound which gives their virtuosity a much less extrovert character. It is hardly surprising that no less a figure than Yehudi Menuhin reacted enthusiastically to these suites—and immediately commissioned Bloch to write a suite for solo violin.

BLOCH’S ‘NIGUN’ IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part One Chapter 3

Now shall I speak of how, in Bloch’s Nigun, over the piano’s rumbling resonance, praise and supplication flowed from your violin as you laid out a rhapsodic line? No, I’ll simply recall how your face glowed with a wild and tender beauty as you played.

Charles Zacherie Landelle, A Jewish Girl of Tangiers

Isidor Kaufmann, Jewish Bride, n.d.

Shall I speak of how the fingers of your left hand rocked as they stopped the strings, inflecting a voice that continually shifted between joy and lamentation? No, I’ll simply mention that in the simultaneous sounding of transgression and transcendence, you made solemnity voluptuous and devotion ecstatic.

BLOCH, THE CELLO & CELLISTS: THREE GUARDIAN ARTICLES

CLICK ON AN IMAGE TO READ THE CORRESPONDING ARTICLE

VIDEO: BLOCH, NIGUN (BAAL SHEM – II)

Cello (Austin Huntington) & Piano (Inyoung Huh)

Violin (Suyeon Kang) & Piano (Daniel Blumenthal)

Violin (Yuri Rapoport) & (West Bohemian Symphony) Orchestra

SPOTIFY: THREE ERNEST BLOCH ALBUMS

Bloch, Cello Suites | Emmanuelle Bertrand

Bloch, Sonatas | Nurit Stark (v.) & Cédric Pescia (p.)

Bloch, Schelomo | Marc Coppey