MOZART

The Violin Sonatas

ANNE-SOPHIE MUTTER ON MOZART’S VIOLIN SONATAS

Vienna critic Walter Dobner interviews Anne-Sophie Mutter about Mozart’s Violin Sonatas

Anne-Sophie Mutter, why do we hear only a few of Mozart’s violin sonatas? Are they really so unattractive to a violinist?

To say ‘only a few’ is something of an exaggeration. The ones that I’ve chosen are the great violin sonatas. The early works have never interested me, as the violin merely accompanies the right hand—as it does with Haydn. Then there are several keyboard sonatas that were later turned into violin sonatas. I think that with our selection of 16 sonatas we have covered three important creative periods in the life of an already mature composer: the Mannheim period and the two phases of his time in Vienna. I’m not out to prove that I’ve recorded all that Mozart ever wrote for the violin and piano. This survey contains the works that are important to me personally and that are central to Mozart’s output as a composer.

Nicolas Lancret, Blind Man’s Buff, n.d.

Luis Paret y Alcazar, Elegant Company Preparing for a Masked Ball, n.d.

The piano is the dominant instrument not just in the early sonatas. In the Violin Sonata in A major K. 526, which dates from the same year as Don Giovanni, 1787, the piano part is one of the most demanding that Mozart ever wrote in a keyboard work. Does this explain why violinists tend to prefer the concertos to the sonatas?

There are also the purely personal predilections of each individual musician. These include a preference for this or that concerto. I don’t think the fact that many of these sonatas are not often played has anything to do simply with the vanity of the violinist. It’s often a lack of interest in chamber music, a genre that lies somewhat off the beaten track. But you find the same elsewhere—with the Beethoven sonatas, for example: of the op. 30 set, the C minor Sonata is often performed, whereas the other two go by the board. Op. 23 is not a popular choice—people prefer the ‘Spring Sonata’ op. 24, even though it really only emerges in its true colours against the background of its darker predecessor, with its sense of inner turmoil. That’s why this Mozart cycle is important to me. Even though chronological considerations play a relatively minor role when compared to Beethoven, it’s wonderful to follow this development from the first Mannheim sonata to one of the last, which Mozart wrote for Regina Strinasacchi.

What criteria did you use in deciding which sonatas to programme as part of your three concerts?

I chose the most important works from all three creative periods—the Mannheim period and the middle and later periods in Vienna. And I tried to order them in such a way that they make musical sense but are also manageable from a technical point of view. One would never start a programme with K. 378, for example: that would be utter suicide. And it also goes without saying that the works that one chooses to open a programme should begin with a fanfare or a similar theme and be very straightforward and extrovert. More introverted works tend to be found in the middle of a programme. It is a question of ensuring that each recital represents a self-contained survey and that a constant development is discernible, culminating in the compositional high point of the programme’s final sonata.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, The Stolen Kiss, 1787-89

Pietro Longhi, La Furlana, 1740-50

You’ve always had a particular predilection for Mozart…

I’ve always been a great lover of Mozart, a great, great admirer of this composer. Perhaps that’s why it seemed so obvious that I should also want to get to know the early works—the so-called ‘lesser’ sonatas—in order to find out more about him as a composer and add to my reputation as a Mozartian. None of these pieces is easy. Mozart has a habit of suddenly demanding that after a wonderfully beautiful elegiac melody you have to perform a triple forward somersault from a standing start. And yet it must never sound merely virtuosic. Mozart’s music is never an end in itself. However much he may have valued virtuosity, it’s always wrapped up in galanterie, elegance and expression. This command of the tiniest nuance and of the mere handful of notes that may be there on the printed page is far more difficult than with Tchaikovsky, for example. There, however bad it sounds, you can simply switch on to autopilot. It’s incredible fun to conjure the notes from thin air. With Mozart not a single note is conjured from thin air. Also, it’s always at a speed that doesn’t really race along. No matter how fast it is, it must always be very controlled.

Mozart speaks of the sonatas that he started in Mannheim in 1778 and completed in Paris as ‘keyboard duets with violin’. How does one interpret this phrase today?

That was simply a formula that people used at that time. It really doesn’t matter if they’re called ‘sonatas for violin and piano’ or the other way round. Neither the violin nor the piano has priority. Without this interaction, chamber music in general is impossible. It’s not a question of who has more notes to play or whose part is more important. Ultimately, the themes are divided equally between the two instruments even in the middle group of works from the Viennese period. I think it’s tremendous that in the late sonatas the violin, together with the piano, already takes over a theme in the middle of the phrase and then hands it back to the piano. Mozart achieves this to magisterial effect in the Sonata K. 454. We shouldn’t direct our gaze at superficialities such as who comes in first or who has more notes to play. It’s simply great chamber music, which demands of both musicians a supreme willingness to listen and a supreme readiness to be honest.

Pietro Longhi, The Faint, 1744

Pietro Longhi, The Mountebank, 1757

‘The young woman is a fright—but her playing is enchanting,’ Mozart described his pupil Josepha Barbara von Auernhammer in a letter to his father. She is the dedicatee of his Op. 2 set of violin sonatas, comprising K. 296 and 376-80, which were described in a contemporary review as ‘unique in kind, rich in new ideas and filled with traces of their author’s great musical genius’. Do you feel, like the reviewer, that they are ‘very brilliant and well suited to the instrument’?

Of course, he dedicated them to Fräulein Auernhammer because of her well-to-do father. He thought very little of her physical appearance and of her abilities as a pianist. Mozart had to keep his head above water. It was a diplomatic move to dedicate these sonatas to this relatively inexperienced pupil. With the possible exception of the Sonata K. 454, which he wrote for Regina Strinasacchi, Mozart was someone who not only took account of the abilities of the works’ dedicatees but who also wrote for himself. Whether the dedicatee could really manage these works was, I think, a matter of some indifference to him.

How do you assess the technical demands of these Mozart sonatas?

In a number of them there are some very tricky bits, something that violinists know very well. In the E flat major Sonata K. 380 there are a number of passages that are decidedly awkward. The sonatas are demanding from first to last. For me, the difficulty of Mozart’s music lies not in the passage-work but in such things as the rondos. Take the rondo of the E flat major Sonata. To what extent should you delay the upbeat, or should you not delay it at all? The phrasing is the big problem, but it is also the key to Mozart’s music. For me, these sonatas are little operatic scenes. If you look at his letters, his handwriting—it very often goes round in a circle. These letters are really miniature works of visual art. Equally striking are the theatrical descriptions that his letters contain. For me, these sonatas are like narratives. Mozart never left the operatic stage, not even in his chamber music. This brings us back to the question of phrasing and to such tiny details as the upbeat or a phrase ending. The upbeats of the dance movements are incredibly important in this respect. Here there are whole worlds for me to explore: the musical structure that has to be brought out.

Pietro Longhi, The Indiscreet Gentleman, n.d.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, Pilgrimage to Cythera, 1717

What is your attitude to Mozart’s final sonatas, to the B flat major Sonata K. 454, for example?

That particular sonata is a monumental achievement. Of all the sonatas, it’s my favourite, with the single exception of K. 304. Mozart achieves such mastery here. In the famous Andante the violin and piano are so elaborately intertwined that you simply don’t notice when the words are taken out of your mouth and put back again. This sonata is infinitely stimulating. And then this Allegretto at the end! This work has a depth that’s unequalled.

MOZART’S VIOLIN SONATA IN B-FLAT MAJOR (K.454) IN ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

FROM ‘MARA, MARIETTA’

Part Nine Chapter 8

How shall I convey the shadow and light of our last evening in Amsterdam? The shadow was within me, the light came from you. In the salon, Klaas, Lia, Joost and I watched you and Ingrid playing Mozart’s Violin Sonata in B-flat major, K. 454. As I listened to you render Mozart’s humanity through your capacity to listen to each other, I thought of Lia’s evolutionary tree—the birds from the reptiles—and wondered: What am I? Marietta, when your gaze met mine on that patio in Princeton, I felt the crack of the egg; I felt my serpent’s tooth making me an opening: I slithered out, I learned to crawl, but I still haven’t learned to fly. When will I? Listen! Your violin effortlessly takes over a theme in the middle of a phrase and then hands it back to Ingrid’s piano, leaving a thrill to run through me. Once again I am blown away by your virtuosity; once again I am moved by your virile femininity: In your flats, T-shirt and jeans, in your black and white and gold and green, you send me as you soar. Listen! You and Ingrid are so entwined that I can’t tell when she takes the cantabile out of your bow and when she puts it back: I simply let the ravishing lyricism of the Andante course through my veins.

Amedeo Modigliani, Self-Portrait as Pierrot, 1915

Juan Gris, Pierrot, 1921

And now once again I am overcome with love, once again I give thanks for the light: And then the shadow falls. I can’t forget the abortive search, the darkness of asylum; I can’t forget the silent screams, the air grabbed in gasps. Yes, I remember the dread of impending madness, the head-banger banging at my door; I remember the days when I couldn’t be still, fearing I’d lose myself, forget to think about myself, slip out of reality. I’d watch the clock, keep busy, for if I didn’t I’d no longer know who I am. I tried to read, but reading had become a game of infinite regression, an exercise in stealth: Persecuted by my own lucidity, obliged to be constantly aware of myself, I couldn’t accept the coin of signifiers lest it depredate my soul. No girl’s touch came to remind me that the most immediate, the most trustworthy, the most integral source of knowledge is the body.

Then again, I didn’t have a body. I was weightless, a wisp of smoke escaping from the citadel of myself, a faint signal of a murdered soul: I was an idiot. Look! Walking across a field of white, a boy feels a tremor running up his spine: He’s just realized the bare feet trudging through the snow are commanded by his mind. Look! The girl in the school bus, the terror in her eyes as the boy stares into them: ‘Know me. I want you to know me’. Look! The creeping rootstalks, the tender grass—look at the boy watching them grow; the mangy dog, the stray cat—see them licking his face. I can’t forget, I can’t forget, I can’t forget! And then once again I am overcome with love, once again I give thanks for the light: You’re tirelessly improvising, creating music in the moment: In the reprise the theme is never the same. Marrying inventive brilliance with intimacy and simplicity, virtuosity and gallantry with purity of soul, you honour the artist whose impeccable taste compelled the chaos at the heart of man to become a cosmos. And I, what am I? Crawling on the ground yet aspiring to fly, what am I?

Egon Schiele, Pierrot (Self-Portrait), 1914

VIDEO: ANNE-SOPHIE MUTTER & LAMBERT ORKIS, 3 MOZART VIOLIN & PIANO SONATAS

E-minor, K. 304

E-flat major, K. 380 (not K. 454)

F-major, K. 547

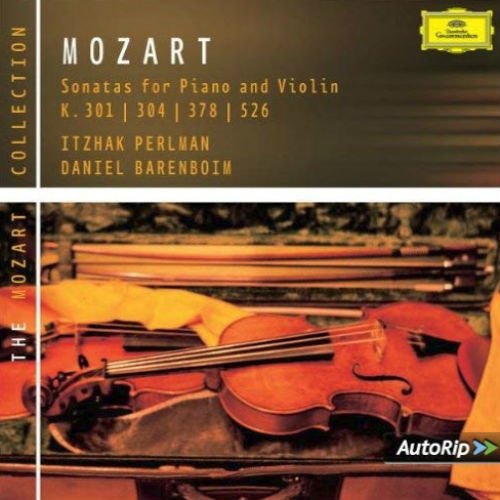

SPOTIFY: THREE MOZART PIANO & VIOLIN SONATAS (K. 526, 454, 376)

Itzhak Perlman & Daniel Barenboim, K. 526

Anne-Sophie Mutter & Lambert Orkis, K. 454

Arthur Grumiaux & Clara Haskil, K. 376

YOU CAN LISTEN TO THE ALBUMS IN FULL WITH A REGISTERED SPOTIFY ACCOUNT, WHICH COMES FOR FREE

MOZART: THREE BOOKS

THE INVENTION OF LIBERTY: JEAN STAROBINSKI ON THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY

From Jean Starobinski, The Invention of Liberty (Geneva: Editions Skira, 1964 | New York: Rizzoli International, 1987) pp. 9-11

Jean Starobinski, The Invention of Liberty

The eighteenth century must be distinguished from its legend. In the early nineteenth century, Europe began to conjure up a nostalgic picture of the preceding century as an age of elegance and frivolity, of sharp wit and uninhibited manners, solely intent on the culpable and delightful pursuit of unrestrained enjoyment. The century of iron, of industry, of democratic revolutions saw another age fading into the past, complete with its masks and gay ribbons, a golden age of mellow, comfortable living, in which even death and war, with their flourish of fine lace, were supposedly neither real death nor real war. Especially after the mid-century the nostalgia and desire for self-justification of the well-to-do led them to construct a philosophy of history—consisting of a mythology of the ancien régime. This philosophy combined a longing for the eighteenth century’s unrestricted gaiety with an indictment of its fatal irresponsibility. For though the bourgeois classes would have liked to retain certain aspects of this vanished age, they were forced to admit that like an attractive fruit hiding and nourishing a worm the eighteenth century contained a sense of nihilism which was to facilitate the development of the ‘subversive spirit.’ The middle classes owed everything to the Revolution, yet they regarded the Revolution as the breach through which evil had entered the world.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, The Italian Comedians, 1720

François Boucher, Girl with Roses, 1760-69

The parks of Watteau, the boudoirs of Boucher, the carnivals of Guardi all seemed to be the images of a paradise already tormented by melancholy at the prospect of its own destruction, mortally wounded by a fault implicit in its pleasures. The official thinkers of respectable society in the nineteenth century deplored the moral corruption of the preceding century; but this same society preferred ‘Louis XV’ furniture, collected libertine prints, and for its amusements dressed up in swords, silk breeches, powdered wigs and black velvet masks … The range of eighteenth-century properties induced an atmosphere of lighthearted love-making, of spicy seduction, of amorous, perfumed conquests. Of course these bourgeois fancy-dress balls were merely imitations; but sanctioned by an ‘artistic’ cult of the past they provided an excuse to evade the repressive rules of a strait-laced ‘Victorian’ morality for the space of an evening. Where the nostalgia of the ‘humanist’ age, from the fifteenth to the eighteenth century, with its classical education, had sought its aesthetic alibi in the pagan myths, the nineteenth century, no longer familiar with Ovid, had recourse to a falsified image of a ‘frivolous’ eighteenth century: a make-believe world in which they could savor theoretically, and therefore inoffensively, the delights of a bygone freedom and licentiousness. Even serious historians tended to evoke an eighteenth century as unlike the reality of that century as the Alexanders and Venuses of the Rococo opera were unlike the gods and heroes of antiquity.

We must try to show the eighteenth century as it really was, in all its complexity and gravity, with its taste for the original reassessments of great principles; for it is still present behind all our contemporary undertakings and problems. We are historians: it produced or at least imposed the modern notion of history. We contemplate the arts: it saw the rise of independent aesthetic reflection. If in the actual practice of the fine arts it was not a century of decisive revolution it was at least open to experimentation, exaggerations and conflicts. Critics and philosophers began to voice their opinions about the arts (sometimes untowardly). For they did not merely argue about the means chosen by the artist, they examined its ends and the possibility of making enlightened judgments which might reveal the essential characteristics of the beautiful and the sublime. The men of the eighteenth century were not content simply to experience the pleasure afforded by works of art: they wanted to assess the particular characteristics of these works and situate them in the perspective of some universal plan of the development of humanity. These anxious critical questions about the function of art did eventually have some effect on the artists themselves, though the aesthetic theories did not necessarily influence them immediately. Diderot’s Salons and his Essai sur la Peinture, Burke’s Enquiry, Lessing’s Laocoon not only commented on works of art already completed, they evoked a still unrealized art and outlined a potential creative mind which the next generation of artists were to emulate in their works and in their lives.

Jean-François de Troy, Astronomy lesson of the duchesse du Maine, 1702-04

Jean-Baptiste-Simeon Chardin, Grapes and Pomegranates, 1763

Diderot had already observed that the language of the theorist is often so vague that the most dissimilar works of art can be embraced by a single statement of abstract principles. ‘How frequently and easily two persons using exactly the same expressions may be thinking and actually saying two quite different things.’ During the century of Enlightenment everyone invoked nature, but each understood nature after his own fashion. Nature according to Hogarth is not nature as Chardin sees it. The history of the aesthetic theories of the eighteenth century would not in itself help us to define the art of the century, for the theorists were blind to many aspects of the art, and the artists for their part were unable to fulfill many of the theoretical requirements. Philosophers (Bosanquet, Cassirer, etc.) and art historians studied respectively—quite independently and each according to his own predilections—the evolution of ideas or artistic creation. This was no doubt a legitimate division of their interests but it is unsatisfactory if we wish to grasp the living reality of the eighteenth century. We must avoid interpreting the art or the thought in isolation from each other—they are largely indivisible, with a common historical and social origin; our task is to unravel and synthesize the complex interrelation of an art moving towards liberation and the highly demanding reflection which was trying to understand this art, to guide and inspire it.

This is a far cry from the image of a frivolous eighteenth century. At the same time, however, the picture of licentiousness to which it has tended to be reduced is not altogether unjustified. It represents one of many experiments possible with liberty: libertinism is an aspect of precisely that liberty without which little progress would have been possible in philosophical reflection. The most representative men of the century desired their freedom in order to seek alike immediate pleasure and fundamental truths; they sought enjoyment, but also critical understanding.

François Boucher, Pan and Syrinx, 1759

François Boucher, Venus Playing with Two Doves, 1754

According to many observers, dissipation was considered a necessary palliative to extreme boredom and despondency: by giving the senses full rein it was supposed possible to gain a clearer awareness of actually being alive. The same held for complete freedom in abstract speculation: the mere act of thinking, however confusedly, involves an implicit ‘I exist’ which could be endangered if speculation were abandoned. To opt for abstract reflection as opposed to sensual libertinism is simply to free oneself to some extent from external objects and seek happiness in the handling of ideas rather than in the immediate sensory pleasures of life.

At the beginning of the century the philosopher John Locke formulated, in theory, this attitude towards life. Opposing Descartes, who maintained that the ‘soul’ thinks continuously, possesses innate ideas and is therefore always assured of its own existence, Locke affirmed that the soul has ideas only after sensations and that thought depends entirely on material supplied by sensory experience: far from being able to depend on innate ideas the soul is only conscious of its existence at the instant of sensation, or when reflection actively compares the traces left by sensations. So nothing is more variable than our consciousness of existing, and nothing is more necessary than to try to vary our sensations and thereby to multiply our ideas. An unoccupied mind is in a sense annihilated. Fortunately, natural human impatience and uneasiness never leave us in peace : we are forever urged to escape from the anxiety of emptiness and to seek, through outside sensations and fleeting thoughts, a fullness and intensity that must be continually renewed. This particular style of living characterizes the aimlessness of the eighteenth century: all its activities are fugitive and ephemeral, from the pursuit of pleasure to the expansion of trading or the exploration of nature, for they belong entirely to the present moment, and that moment is instantly past.

Jean-Antoine Watteau, The Pleasures of Love, 1719

Henry Fuseli, The Nightmare, 1781

Yet beyond what has been attained, and thereby lost, our uneasiness perceives a new requirement in which life may find confirmation and renewal. To avoid absolute dejection men need to provide themselves with passions: this is the lesson running through a book which was to exert a lasting influence on the aesthetics of the eighteenth century, the Réflexions critiques sur la poésie et la peinture by the Abbé Du Bos (1718): ‘The soul, like the body, has its particular needs. One of man’s greatest needs is to have his mind occupied. Boredom follows close on inaction of the mind and to avoid the torments of this painful evil men often undertake the most demanding tasks. The excitement caused by our passions, even in solitude, is indeed so keen that any other state is by comparison nothing more than dull inertia. So we instinctively seek out objects capable of exciting our passions, even though these objects may give rise to confusion of mind, restless nights and days of anguish: but as a general rule men suffer more from the absence of passions than from the anxieties caused by these passions.’

From the outset, the theoretical reasoning of this ‘rationalist’ century recognized the absolute domination of passion in poetry and the fine arts. It is true that the images of the passions evoked in 1718 are not so vehement as those of the Romantics, but from the very beginning the work of art was given the psychological function of exciting the emotions through surprise and intensity. The work could be defined in terms of its subjective effect: it was to jolt the mind out of sluggishness and idleness, and by means of vivid images evoke an instant of high emotion and excitement, of mental or physical stimulation. Following the tradition of profane humanism, art was directed towards the individual—amateur or specialist. With the invention of perspective, as Panofsky has shown, a picture is presented to an individual consciousness which is in the privileged position of controlling the ‘point of view’ around which the pictorial space is organized.

Jean Raoux, Young Woman Reading a Letter, n.d.

Jean-Honoré Fragonard, Inspiration, 1769

If, as a result, this isolated human consciousness comes to experience its own ‘duration’ as a succession of intermittent instants, divided by long periods of negation, this will not deprive it of its central, privileged position; in the event, however, we find that aesthetic emotion was merely one of the resources which men used excessively in order to intensify and stimulate the momentary joy of sensing their own vital existence. Consequently art itself was to become more expressive, impetuous, delicate; by an ever more vivid representation of anguish, pleasure or uncertainty art could the better induce these emotions in the observer. Images were therefore to be used for their inherent ‘eloquence,’ for the moral value of their narrative content; pictures were to represent a moment of pathos, or a witty, piquant scene, so that the observer’s sympathetic reaction might produce in him an analogous emotion, a compassionate or a terrified response. A fleeting moment of time, caught and immobilized in the painting, was to combine immediate impact with discursive statement.

But the ‘enlightened’ man who constantly claimed the right to contradict all previously accepted authorities acquired thereby a sense of oppositions which enabled him also to contradict himself. For all its temptations and cherished formulas, the eighteenth century fostered a lively spirit of criticism and sometimes a resolute and viable self-criticism, with a desire to experiment with opposites. Thus, during the Neoclassical period, a taste for depicting eternal beauty was to replace the immediate fleeting enjoyments of the Rococo: mobility of expression wished to be forgotten in immobility of form.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait in a Straw Hat, 1782