THE ART OF ACTING: FILM ACTRESSES & GLOBAL CLASSICS

My reflections on actresses and their most compelling performances in (mostly) classics of global cinema

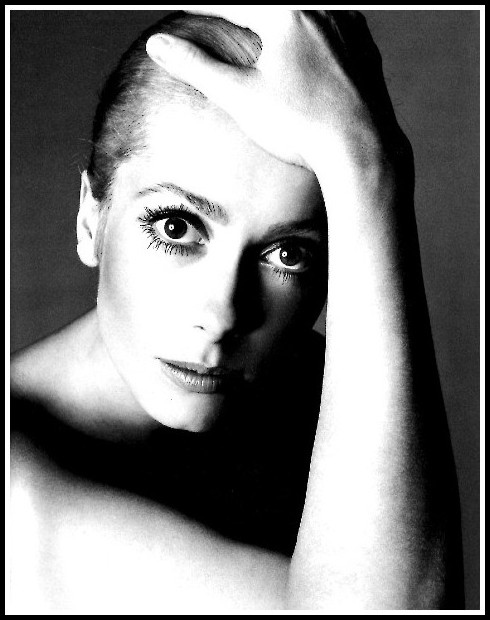

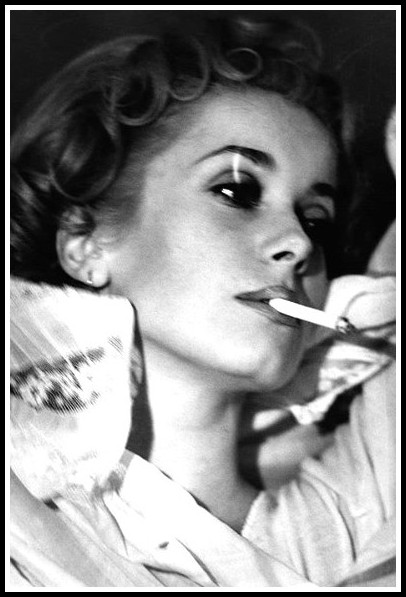

Catherine Deneuve | Photo: Richard Avedon, 1968

CATHERINE DENEUVE ACTRESS, PART 1 OF 4: INTRODUCTION

Richard Jonathan

Catherine Deneuve | Photo: Richard Avedon, 1968

Catherine Deneuve, in Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965) and Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967) and Tristana (1970), illuminates the screen with her signature ‘presence’ and in so doing, contributes greatly to making these films classics of global cinema. In no other of the dozen or so of her films I’ve seen is her signature so apparent. Why? In this post I will argue that these three films, each in its own way, was the occasion for a synergistic conjunction of woman, actress, screenplay, role and director, and as such generate an energy that makes the films as compelling today as they were at the time of their release.

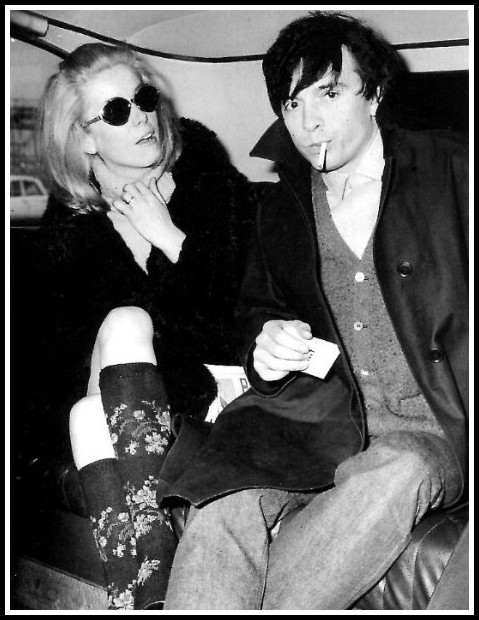

Catherine Deneuve & David Bailey, 1966

Susanne Valerie Granzer, in her philosophical reflection on the art of acting (Actors and the Art of Performance: Under Exposure), writes: ‘Acting is sensuous, contradictory, performative and ecstatic. It thus always includes an incalculable, unpredictable moment, an increase of being. The result of a performance is not logical, but ontological. It cannot be summed up with arguments. Its character is more of an erotic nature. Desirable, coupled. Every performance is a copulation, a copula, an amour fou’. She defines ‘the distinctive eros of the actor’ as ‘the demonic, the erotic act of play that couples the canny with the uncanny’. The actor’s art as demonic and erotic: this vision will inform my reflections on Catherine Deneuve as an actress.

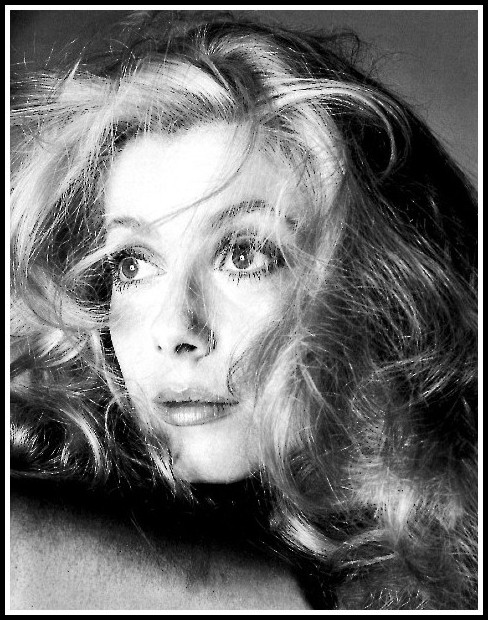

Catherine Deneuve (detail) | Photo: David Bailey

The medium of the actress’ art is herself—her body/voice, her self-experience, the distillates of her encounters with others and the world. How she gives form to feeling is a function of what she’s made of her experiences—sensual and intellectual, emotional and spiritual. What can be said of Catherine Deneuve regarding the relation of woman to actress? I offer first my vision of the woman then, in the discussion of the films to follow, my vision of her relation to the actress.

Catherine Deneuve | Photo: David Bailey

Catherine Deneuve is not neurotic. She fell into acting by accident, learning her craft through the adventure of filmmaking, and continued only because she enjoyed it. Consequently, unlike so many actresses who seek in their art (unconsciously, of course) a means of self-healing, she is fundamentally a free woman, not driven by any compulsion. This aspect of the woman is one determinant of her screen persona, that ‘presence’ characterized by ironic distance and alert detachment. As she said in an interview (my translation), ‘I have a critical frame of mind, an ironic disposition, because my father raised us that way. He taught us at an early age that it’s important not to yield to admiration, at least not for one’s looks. And he wanted us to always be lucid about people, to see them as they are’. And indeed, every interview Deneuve has given confirms her lucidity and independence, her free-thinking derived from lived experience, influenced neither by formal education nor intellectual fashion.

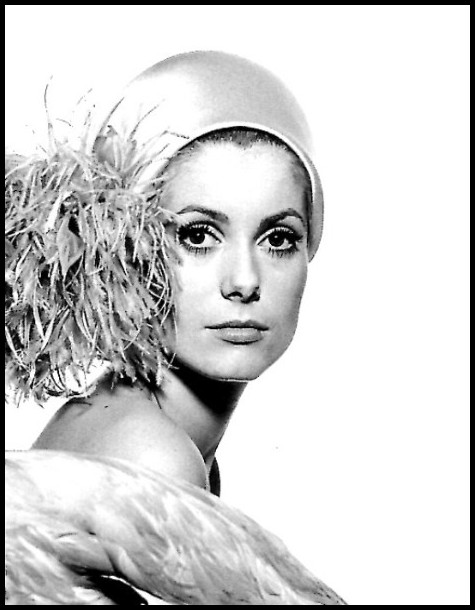

Catherine Deneuve, Repulsion, Roman Polanski

Another determinant of Deneuve’s screen persona is, of course, the particular quality of her beauty, that marriage of sculptural elegance and sidereal coldness. But what is Deneuve’s self-experience in this regard? It’s entirely consistent with her freedom and lucidity. See, for example, this interview. Going further, Giorgio Agamben’s remarks on ‘the nihilism of beauty’ (in Nudities) strike me as particularly relevant to Deneuve: ‘The ‘nihilism of beauty’ consists in reducing one’s own beauty to pure appearance and then exhibiting this appearance with a sort of remote sadness, stubbornly denying the idea that beauty can signify something other than itself. But it is precisely the very lack of illusions about itself—this nudity without veils that beauty thus manages to achieve—that furnishes the most frightful attraction.’ Indeed. And Deneuve herself says (in the same interview cited earlier, my translation): ‘The importance of the image frightens me because what people say about me and how I perceive myself are out-of-synch. Right from the time I was very young, the image has always seemed dangerous to me’.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

The raw material of Deneuve’s acting, then, her body/voice and life experience, are characterized by freedom, lucidity and the nihilism of beauty. Let’s now take a look at how she transforms that material into three of her greatest roles: Part 1: Carole Ledoux in Roman Polanski’s Repulsion (1965); Part 2: Séverine/Belle de Jour in Luis Buñuel’s Belle de Jour (1967); Part 3: Tristana in Buñuel’s eponymous film (1970).

Catherine Deneuve, Tristana, Luis Buñuel

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

FILM ACTRESSES & GLOBAL CLASSICS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK OR TAP ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2020 | All rights reserved

Comments