BELLE DE JOUR – LUIS BUÑUEL

The Art of Acting: Film Actresses & Global Classics

Catherine Deneuve – Tristana, Repulsion, Belle de Jour

CATHERINE DENEUVE ACTRESS, PART 3 OF 4: BELLE DE JOUR (LUIS BUÑUEL)

Richard Jonathan

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Belle de Jour opens with Séverine and Pierre riding through the forest in a horse-drawn carriage. Their dialogue goes like this:

– Shall I tell you a secret, Séverine? Every day I love you more.

– So do I, Pierre. You’re all I have in the world. But…

– But what? I too wish that everything could be perfect. If only you were less cold.

– Don’t mention that anymore, please!

– I didn’t mean to upset you. You know my tenderness for you is immense.

– And what good is your tenderness to me?

– You can really be mean to me when you want to.

– Forgive me, Pierre.

Jean Sorel & Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Pierre then asks the coachmen to stop. He orders Séverine to get out of the carriage. She refuses. He then has the coachmen pull her out and drag her into the forest. Under a tree they bind her wrists, throw the rope over a branch and hoist up her arms. They then proceed to whip her, until Pierre stops the lead coachman and says, ‘She’s yours now’. As the coachman stands behind her and kisses her neck, she looks up in ecstasy.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

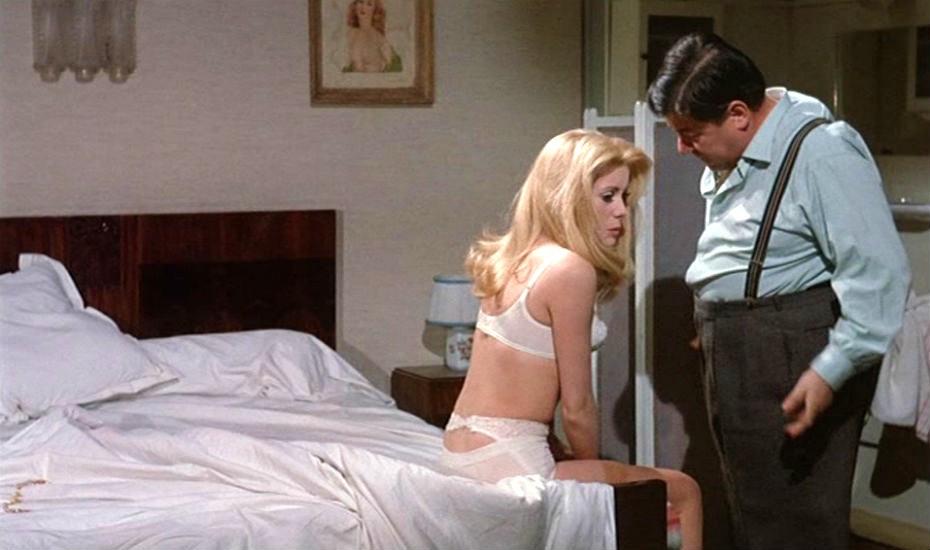

We then hear Pierre asking, ‘What are you thinking of, Séverine?’ and cut to Pierre putting on his pyjama top in the bathroom mirror while Séverine is seen lying in bed. He turns around and repeats his question directly; she answers, ‘I was thinking about you. About the two of us. We were taking a ride together in the carriage’. He responds: ‘The carriage again?’. The scene concludes with Pierre telling Séverine that, to celebrate their first wedding anniversary, they’re going to a ski resort the next day. He takes a moment of tenderness between them as an opportunity to share her bed; she refuses him and asks for his indulgence: he grants it.

Jean Sorel & Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Two scenes suffice, then, to make it clear that the heart of the film will be the split in Séverine between love and desire. Her husband, Pierre, will only ever be an object of her love, never of her desire: for that, she will have to look elsewhere. So, while she will never seek to play out her specific fantasies of violation, the cold wife will, after some hesitation, become a hot whore (Belle de Jour): a plain apartment, an accommodating madam, and a clientele with an exotic touch will enable her to attain the elusive realm of the orgasm.

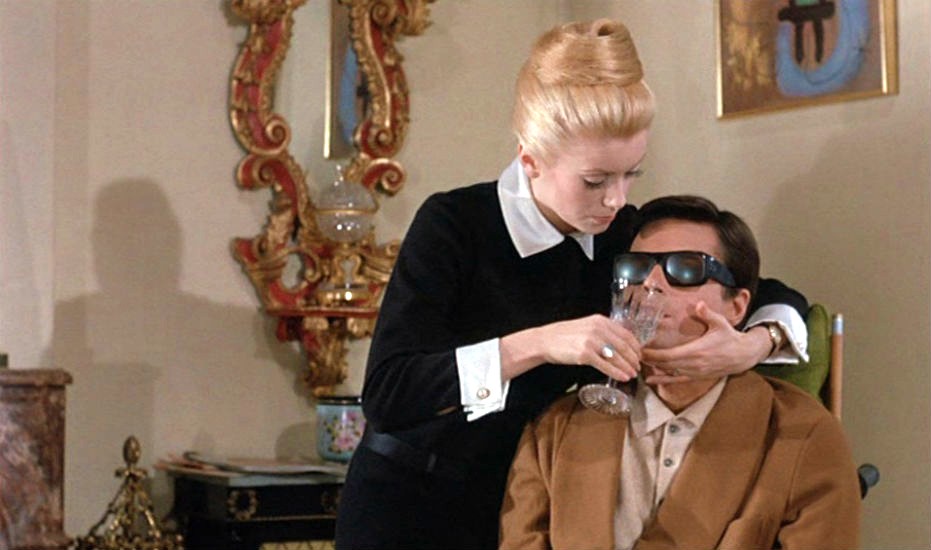

Catherine Deneuve & Francis Blanche, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Drama comes in the form of Marcel (Pierre Clementi), a gangster who falls in love with Belle de Jour. If, for Séverine, no-one could ever replace Pierre in her heart, the wilderness of pain in Marcel’s eyes solicits her affection. What really draws her to him, however, is his aura of danger, the ever-present intimation of violence: in bed, the cruelty that shadows his tenderness never fails to take her over the edge.

Catherine Deneuve & Pierre Clementi, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

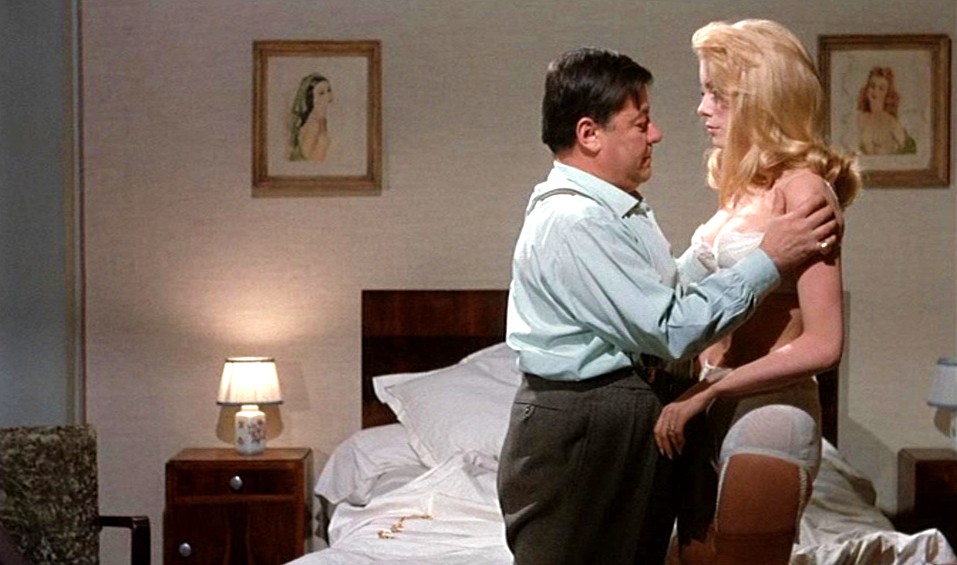

But, as the saying goes, ‘love spoils everything’: Marcel becomes possessive, wants to spend not only his jours with Belle but also his nuits. She’ll have none of it, of course: Pierre is her one and only, love and desire must remain separate—she can’t imagine sexual satisfaction if the two converge in one man. And so Marcel shoots Pierre, making of him a wheelchair-bound paralytic. And it is now that Séverine’s masochistic fantasies give way to dreamless nights and serene days: paralytic Pierre, incapable of sex, has resolved her struggle between love and desire.

Catherine Deneuve & Jean Sorel, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

And then Pierre rises miraculously from his wheelchair and asks Séverine what she’s thinking—she replies that she’s thinking of him. The repetition of dialogue from the film’s second scene continues with the couple agreeing to holiday again in the mountains. The porosity between fantasy and reality, it seems, will never be resolved: Séverine, prompted by the same jingling bells that accompanied their initial carriage ride, steps out onto the balcony and sees the horses drawing the carriage through the forest as before. This time, however, the carriage is empty. Has Séverine, then, thanks to her fantasy, been able to both love and desire her husband? Has her enactment of the fantasy of prostitution been effective in her self-cure? Will the soul of dead Marcel (he dies a gangster’s death in a shoot-out in the street) somehow lend its virility to Pierre, will Pierre at last know how to ‘take’ Séverine, will he understand that she needs to be ravished in order to enter that realm she so longs for? Questions, questions, questions: Art is always intimate with the erotics of knowledge.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Now why is Catherine Deneuve so effective as Séverine/Belle de Jour? Again, as in Repulsion (a post wherein, by the way, you will find a more elaborate exposition of feminine sexuality than the one given here), the brilliance of her performance is largely due to the quality of her ‘presence’ and her mastery of subtle movement. To see how this works in Belle de Jour specifically, consider, first, these two theses (by Georges Bataille and Susan Sontag, respectively):

GEORGES BATAILLE: ‘If beauty so far removed from the animal is passionately desired, it is because to possess is to sully, to reduce to the animal level. Beauty is desired in order that it may be befouled; not for its own sake, but for the joy brought by the certainty of profaning it. To despoil is the essence of eroticism. Humanity implies taboos, and in eroticism they are transgressed, humanity itself is transgressed, profaned and besmirched. The greater the beauty, the more it must be befouled.’ (Georges Bataille, Eroticism, Penguin Classics, 2001) pp. 144-45

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

SUSAN SONTAG: ‘There is something incorrectly designed and potentially disorienting in human sexual capacity. Man, the sick animal, bears within him an appetite which can drive him mad. Human sexuality is something beyond good and evil, beyond love, beyond sanity; it is a resource for ordeal and for breaking through the limits of consciousness.’ (Susan Sontag, ‘The Pornographic Imagination’)

Catherine Deneuve & Pierre Clementi, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Now let’s consider the implications of the aforementioned statements. In Belle de Jour, Deneuve puts her capacity for self-containment, her ability to employ her body as a shield for her interiority, in the service of the mystery of Séverine’s desire. In her key encounters, Séverine’s eyes alone deign to engage while her face flaunts its regal splendour and her body stands aloof. It’s as if she secretes a zone of intimacy around herself, a magnetic field that repels as it attracts. As every woman knows, indifference only intensifies desire, and thus it is that the erotic charge she generates—in her co-characters on the screen and in the film spectators in front of it—springs from their desire to see her beauty befouled. Is that not our secret pleasure in seeing Séverine stripped of her Saint-Laurent suit, of seeing her stockings at her ankles as she’s being dragged along to be whipped, of seeing her porcelain beauty splattered with mud? Those out of touch with the wellspring of their sexuality may find their pleasure guilty, while more in-touch men and women will thrill to the correspondences between Séverine’s desire and their own.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Deneuve’s natural stance of ironic distance gives her that paradoxically appealing air of detachment, and when the role requires it, she can raise the temperature of her partner/the spectator even as she lowers her own to ice. Personally, I am charmed by her acting (meaning its ‘magic’—indispensable in art—works on me), and I think that is due to her ability to assert her subjectivity even as she plays at being an object. In a word, the way she assumes, in Belle de Jour, the nihilism of beauty while pursuing carnal knowledge is nothing short of magnificent.

Catherine Deneuve & Pierre Clementi, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

CATHERINE DENEUVE: ‘I think beauty can inhibit a woman’s sexuality. I don’t think it’s necessarily an advantage. A beautiful woman obviously generates a desire, and, feeling desired in someone’s eyes, she can, by reflection, feel desire herself. But that doesn’t solve the problem of her own desire.’ (Interview in L’En-je lacanien, my translation.)

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

WOMEN’S EROTIC FANTASIES: JEAN-CLAUDE CARRIÈRE ON WRITING ‘BELLE DE JOUR’

The ‘realistic’ part is fake and the ‘fantasy’ part is true

On the basis of Joseph Kessel’s novel, Jean-Claude Carrière co-wrote Belle de Jour with Luis Buñuel. The following text is a transcription (edited for greater readability) of a segment of an interview Carrière gave for the Studio Canal DVD of Belle de Jour (one of eight films in ‘The Luis Buñuel Collection’ box set).

For the first time in film history we had the opportunity to deal, in a perfectly clear and obvious way, with female erotic fantasies. If we could develop the fantasy part with Séverine, the heroine, we had the opportunity to insert into the film, beyond what’s in the book, a brand-new dimension, and to do it as two men talking about a woman’s fantasies. It was a good opportunity for us, and so it became absolutely necessary to get information about women’s erotic fantasies. We met many psychiatrists and also a lot of prostitutes, in Madrid and in Paris. We chatted with brothel-keepers. I also asked a journalist friend to investigate.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

The end result is that, in the movie, the ‘real’ part is fake and the’ fantasy’ part is true. Séverine’s story, her husband and Mr Husson’s stories, are conventional, they come directly from the novel, while all the fantasies described in the film come from real life, they’ve been experienced by women who told us about them. So the funny thing about Belle de Jour is that the so-called ‘realistic’ part is unrealistic and the ‘fantasy’ part is true.

Jean Sorel & Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Another thing we realized during the writing is that every time we tried to make what Séverine did seem realistic by choosing, from among ten fantasies we had been told, the one that seemed closest to her—to her social class, her age, her looks, her relationship with her husband—we were dealing with so-called ‘masochistic’ behavior. At a certain point we realized it, we realized we were making a portrait of a masochistic woman who lived out her fantasies, or at least tried to live them out, for in her real life, as an amateur prostitute, she never reaches the satisfaction she gets from her fantasies. When we found this little ‘key’ that a psychiatrist gave us, the path for the film was clear.

Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

Later, when the film was finished, Lacan did a few seminars where he told his students, ‘I wanted to talk about female masochism, but now that the film Belle de Jour is out, I’m going to show it to you instead.’ He just let the film speak for itself, and I actually saw students taking notes during the projection.

Francis Blanche & Catherine Deneuve, Belle de Jour, Luis Buñuel

FILM ACTRESSES & GLOBAL CLASSICS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK OR TAP ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments