THE ART OF ACTING: FILM ACTRESSES & GLOBAL CLASSICS

My reflections on actresses and their most compelling performances in (mostly) classics of global cinema

Nicole Kidman – The Portrait of a Lady | Eyes Wide Shut | Dogville

NICOLE KIDMAN ACTRESS, PART 4 OF 4: DOGVILLE (LARS VON TRIER)

Richard Jonathan

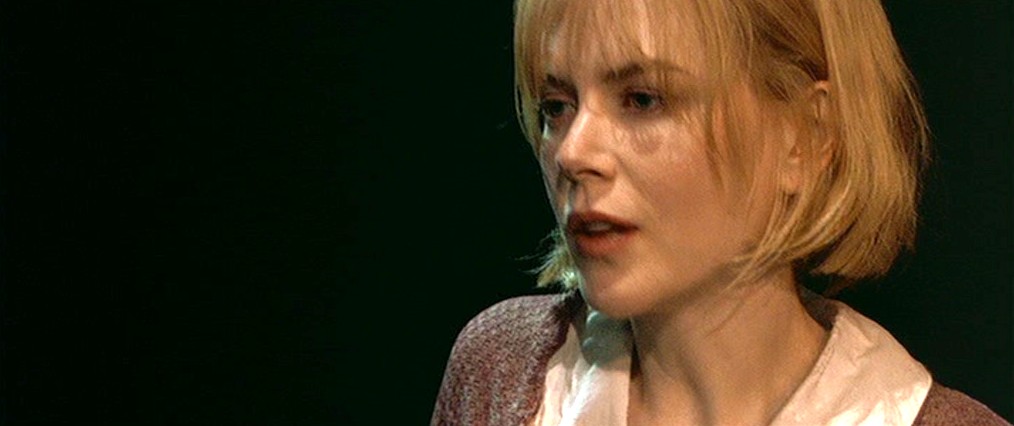

Nicole Kidman as Grace, Dogville, Lars von Trier

In the morass of hackneyed filmmaking that clutters global screens, the derring-do of Dogville restores the honour of art, reminding us that without risk vitality is lost, be it in cinema or life itself. By filming on a bare stage, Lars von Trier staked his film on the strength of its writing and the effectiveness of its acting. If Dogville succeeds so brilliantly, then, it is primarily due to the quality of von Trier’s screenplay (praised by, among others, Quentin Tarantino) and to Nicole Kidman’s acting (and that of the whole cast). In considering the work of the actress, we must bear in mind Dogville’s formal specificities. The film is a fable (or parable, if you prefer), and so the premise of psychological veracity implicit in its naturalistic acting is complicated by the artificiality inherent in the fable.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

In playing Grace, then, Kidman’s challenge was to maintain a constructive tension between naturalness and artificiality: under Lars von Trier’s direction she walks this tightrope brilliantly, displaying in equal measure dexterity and aplomb. Von Trier wrote the film for Kidman, and he says of her performance: ‘I think she’s incredibly good in the film, a real asset. I was asking her to do things in front of the camera that were pretty demanding, and she just did them’ (Trier on von Trier, ed. Stig Björkman. Faber & Faber, 2003; p. 249).

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

What is the dramatic premise of Dogville? It goes like this. Into the sleepy hamlet of Dogville USA, a stranger appears, preceded by gunshots. Her name is Grace. Turns out she’s a fugitive, on the run from gangsters. Tom, a would-be writer and the town’s resident thinker, is bent on ‘morally rearming’ Dogville. He wants to ‘refresh folks’ memory of what this country has forgotten’, and he wants to do so by ‘illustration’. What ails the town, in his eyes, is that ‘the people of Dogville have a problem with acceptance’. For them to see this, what they really need is ‘something to accept, something tangible, like a gift’. And thus Grace becomes the gift that enables Tom to conduct his exercise in illustration, his social experiment aiming to reveal that the residents of Dogville have lost the ability to receive.

Udo Kier, Jean-Marc Barr & Paul Bettany, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Grace needs a refuge, Dogville needs a lesson and Tom needs an illustration: this is the film’s dramatic premise, the tripartite accord that drives the film forward to the riot of revenge that is its ending. Note that as co-experimenters Tom and Grace are complicit, and so their conversation with each other is far more intimate and frank than is their talk with the rest of the town. This split that separates Grace and Tom from the other people in Dogville poses a second acting challenge for Kidman: she is called upon to collude with ‘insider’ Tom while preserving her status of ‘outsider’—in other words, to walk another tightrope.

Paul Bettany & Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

In terms of dramaturgy, the gradual escalation of Grace’s abuse at the hands of the residents of Dogville, culminating in her enslavement and subjection to systematic rape, is psychologically coherent and artistically compelling. More problematic, in the eyes of many, is the ending, where the once-all-forgiving Grace ferociously enacts her vengeance. Lars von Trier himself has said: ‘My biggest problem with the story was trying to explain Grace’s change of attitude at the end. Admittedly the people of Dogville, who have long exploited her, become more and more demanding and cruel, but I still had trouble explaining Grace’s conversion’. And: ‘Grace acts good-heartedly, but she isn’t – and will not be – a ‘gold heart’ figure. She has to possess a capacity for something else. I tried two or three tricks to get it to work, but I don’t know if it does.’ (Trier on von Trier, ed. Stig Björkman. Faber & Faber, 2003; p. 252).

Stellan Skarsgård & Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

For me, the ending is very effective; the feast of vengeance works because, consistent with the entire film, it takes place in the register of fable. Those who see the film as a morality play twist themselves into a pretzel trying to account for the ending. Indeed, by what morality can mass murder be justified? None.

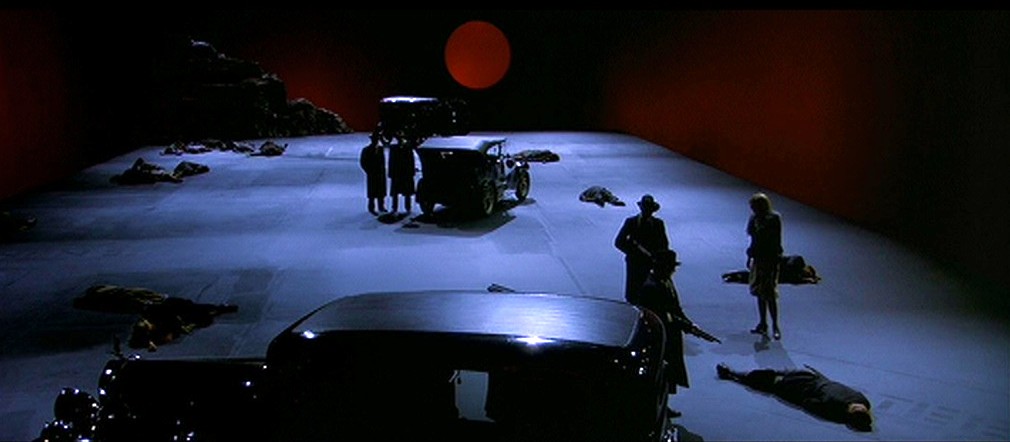

Feast of vengeance, Dogville, Lars von Trier

And yet, if in our heart of hearts we all know that ‘revenge is a great narrower of the mind’, that it ‘excites and oversimplifies in one fell swoop’, that it ‘answers the two essential questions—what has happened? and what is to be done?—with militant certainty’ (Adam Phillips, In Writing: Essays on Literature, Penguin Books 2017), we also know that Grace’s ‘militant certainty’ is not the outcome of a narrowing of the mind and oversimplification. On the contrary, her long dialogue with her father and her solitary walk before making her decision show us how richly she has reflected, how her feelings and thoughts evolved before finally converging on the decision that Dogville must die. Dramatically, this is the most highly-charged moment in the film, and to render it Kidman conveys at once a fierce determination and an existential lassitude: thanks to her performance, it works brilliantly.

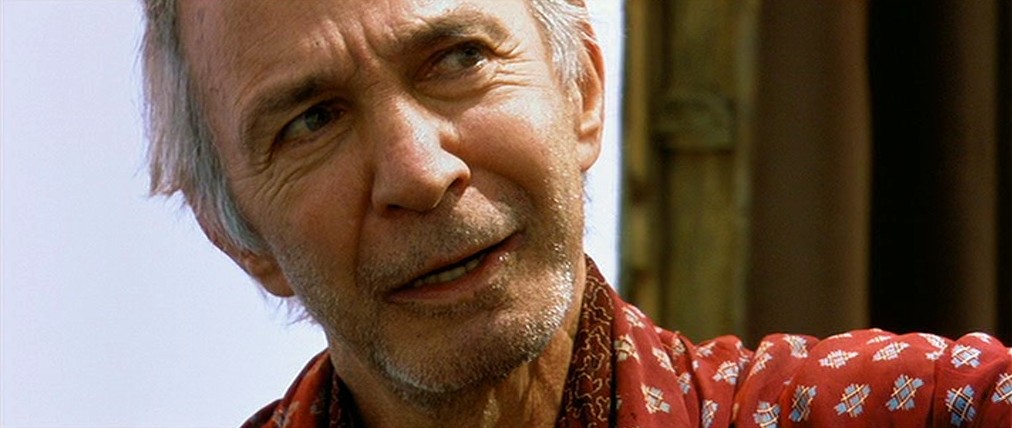

Nicole Kidman and James Caan, Dogville, Lars von Trier

It was while listening to a recording of ‘Pirate Jenny’ (Brecht-Weill, The Threepenny Opera) that von Trier decided he wanted to make a film about revenge. What got him going in particular was the line, ‘And they asked me which heads should fall, and the harbour fell quiet as I answered, All!’ (Trier on von Trier, ed. Stig Björkman. Faber & Faber, 2003; p. 244). In the same interview, he goes on to add that he thought ‘the most interesting thing would be to come up with a story where you build up everything leading to the act of vengeance … Women’s vengeance is considerably more interesting to deal with than men’s. It’s more exciting. In some strange way it seems that women are better at embodying and expressing that part of me. The feminine part of me, perhaps! I find it easier to excuse myself and my thoughts if I allow them to be expressed through a woman. If I expressed the same thing through a man, you would only see the brutality and cruelty’ p. 244 and 253-54).

‘There’s a family with kids. Do the kids first and make the mother watch. Tell her you will stop if she can hold back her tears.

I owe her that. I’m afraid she cries a little too easily.’

Those viewers tempted to see the film as a thesis would do well to bear these remarks in mind. Indeed, art can never be reduced to any other discourse, and one can only be thankful that von Trier has such trust in his artistic instincts.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Watching Dogville, I am struck by how beautifully Kidman maintains Grace’s aura of innocence throughout the film, inflecting it just enough to register experience at the end (all the more impressive as Lars von Trier had the camera harnessed to his body and, while operating it, would speak to the actors, obliging them, as Kidman remarked, ‘to put oneself into a state where one can hear his voice without letting it distract you’ (interview in Le Monde, 21 May 2003).

Nicole Kidman & Lars von Trier making Dogville

Maintaining this quality of innocence at just the right pitch for every scene is a great challenge, and Kidman’s success in meeting it contributes greatly to making Dogville work so well as a film about the ‘innocent other’, the stranger who enters a community and, by his/her very innocence, disrupts it and shows it its true face.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

In this, Grace has something in common with the Guest (the Terence Stamp character) in Pasolini’s Teorema. A comparison with Jesus Christ is equally evident and, were one to pursue it, one would have to address the theme of the scapegoat as developed, in particular, by René Girard. The comparison I’d like to pursue here, however, is that with Billy Budd, the hero of Herman Melville’s 1891 fable, Billy Budd, Sailor.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

In Billy Budd, Sailor, the community is the captain and crew of a warship and the ‘other’ is Billy Budd, a sailor of exceptional innocence and beauty. Claggart, a sailor of higher rank than Billy, comes to despise Billy precisely because of what sets him apart: his implicit appeal to what’s best in people, his unselfish concern, alien to calculating egoism. When, before the captain, Claggart falsely accuses Billy of plotting mutiny, Billy can’t get the words out to defend himself (he is prone to stuttering), and ends up throwing a punch that inadvertently kills Claggart. The captain calls a summary trial, Billy is found guilty of the murder of a superior, and is promptly hanged. I contend that the two fables, Billy Budd, Sailor and Dogville, make the same point: the immaculate hero or heroine, no less than the vile villain, bears the mark of Cain. Kind-hearted Grace, the ‘beautiful fugitive’, is a cousin of Billy Budd, the handsome sailor of unselfish concern.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Hannah Arendt in her book, On Revolution, asserts that we can learn from the poets that ‘absolute goodness is hardly any less dangerous than absolute evil, that it does not consist in selflessness’. If Melville and von Trier both make this point, the difference is that Melville confronts absolute goodness, goodness beyond virtue (Billy Budd) with absolute evil, evil beyond vice (Claggart) whereas von Trier, while leaving open the possibility that Grace’s goodness is absolute, ‘complicates’ it with the argument, advanced by her gangster-boss father, that it is in fact extreme arrogance.

Nicole Kidman and James Caan, Dogville, Lars von Trier

If some will have felt this all along, it is only at the end of the film that it is voiced, with Grace’s father saying, for example, ‘You have this preconceived notion that nobody can possibly attain the same high ethical standards as you, so you exonerate them. I cannot think of anything more arrogant than that. You, my child, my dear child, you forgive others with excuses that you would never in the world permit for yourself’. Kidman, here, has to show via her body/voice the struggle taking place in her mind. As the whole scene is filmed entirely in close-ups, she uses her face to portray the growing doubt about her own convictions, her advances and retreats in the battle with her conscience.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

There is no Claggart figure in Dogville. The film shows how the residents bond together in both evil and good. Nevertheless, it casts a particularly cold eye on how these ‘good, honest folk’ self-righteously go down the slippery slope we recognize as ‘the banality of evil’, the group dynamics that lead them to enslave and dehumanize Grace. Thus, all the men who rape Grace keep a clean conscience because, as the narrator puts it, ‘since the chain had been attached things had become easier for everyone. The harassments in bed did not have to be kept so secret anymore, because they couldn’t really be compared to a sexual act. They were embarrassing in the way it is when a hillbilly has his way with a cow, but no more than that’.

Ben Gazzara & Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Von Trier does not only highlight collective responsibility, however; he also uses his gift for irony to show individual responsibility. Take Chuck’s wife, for example, of whom the narrator says, ‘Now that Vera had received proof that it was in fact Chuck who’d forced his attentions on Grace, she was meaner than ever’. Kidman, in playing the understanding victim of the residents’ vileness, again has to walk a tightrope, this time one with the viewers’ pity for her suffering on one side and their contempt for her passivity on the other. Again, she walks this high wire with dexterity and aplomb, leading us to question our changing responses to Grace and thereby fulfill the Brechtian ideal of spectators at once emotionally engaged and intellectually aware.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Nicole Kidman, because of her vast range and versatility and the radiance of her feu sacré, is (as I wrote in Part 1 of these posts) the finest actress, in my view, in English-language cinema today. The three films I’ve discussed in this series all draw fully on her talent. My fervent wish now is that she make more films that are worthy of her, for to date (August 2018) there are pitifully few in her filmography.

Nicole Kidman, Dogville, Lars von Trier

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

THE ‘GOOD, HONEST FOLK’ OF DOGVILLE

Freud on ‘Love Thy Neighbour’

The problem of ‘why good people do bad things’, of why ‘good, honest folk’ commit vile acts, has been studied from various perspectives: sociological (Zygmut Bauman, Liquid Evil); behavioural (Dan Ariely, The Honest Truth About Dishonesty); dramatic (Antigone, The Crucible, Marat/Sade); historical (Christopher Browning, Ordinary Men; Hannah Arendt, The Banality of Evil); political (Theodor Adorno, ‘Freudian Theory and the Pattern of Fascist Propaganda’), and psychoanalytic (Freud, Mass Psychology and Analysis of the ‘I’, Civilization and Its Discontents), among others. To accompany the following images of the ‘good, honest folk’ of Dogville, I’ve selected a few passages from Civilization and Its Discontents (tr. David Mclintock, Penguin Books ‘Great Ideas’, 2004), 60-62 &, for the last 3 passages, tr. James Strachey (Norton, 1989), 66-69.

Mission House meeting, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Human beings are not gentle creatures in need of love, at most able to defend themselves if attacked; on the contrary, they can count a powerful share of aggression among their instinctual endowments.

Patricia Clarkson as Vera, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Hence, their neighbour is not only a potential helper or sexual object, but also someone who tempts them to take out their aggression on him, to exploit his labour without recompense, to use him sexually without his consent, to take possession of his goods, to humiliate him and cause him pain, to torture and kill him. Man is a wolf to man. Who, after all that he has learnt from life and history, would be so bold as to dispute this proposition?

Željko Ivanek as Ben, Dogville, Lars von Trier

As a rule, this cruel aggression waits for some provocation or puts itself at the service of a different aim, which could be attained by milder means. If the circumstances favour it, if the psychical counter-forces that would otherwise inhibit it have ceased to operate, it manifests itself spontaneously and reveals man as a savage beast that has no thought of sparing its own kind.

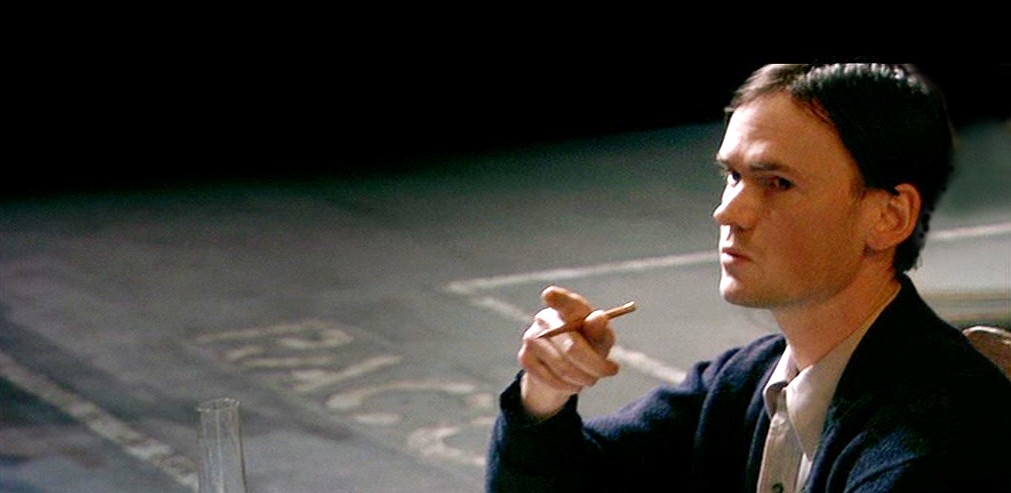

Paul Bettany as Tom Edison Jr., Dogville, Lars von Trier

Whoever calls to mind the horrors of the migrations of the peoples, the incursions of the Huns, or of the people known as the Mongols under Genghis Khan and Tamerlane, the conquest of Jerusalem by the pious Crusaders, or indeed the horrors of the Great War, will be obliged to acknowledge this as a fact.

Stellan Skarsgard as Chuck, Dogville, Lars von Trier

It is the existence of this tendency to aggression, which we detect in ourselves and rightly presume in others, that vitiates our relations with our neighbour and obliges civilization to go to such lengths. Given this fundamental hostility of human beings to one another, civilized society is constantly threatened with disintegration. A common interest in work would not hold it together: passions that derive from the drives are stronger than reasonable interests.

Jeremy Davies as Bill Henson, Dogville, Lars von Trier

Civilization has to make every effort to limit man’s aggressive drives and hold down their manifestations through the formation of psychical reactions. This leads to the use of methods that are meant to encourage people to identify themselves with others and enter into aim-inhibited erotic relationships, to the restriction of sexual life, and also to the ideal commandment to love one’s neighbour as oneself, which is actually justified by the fact that nothing else runs so much counter to basic human nature.

Ben Gazzara as Jack McKay, Dogville, Lars von Trier

For all the effort invested in it, this cultural endeavour has so far not achieved very much. It hopes to prevent the crudest excesses of brutal violence by assuming the right to use violence against criminals, but the law cannot deal with the subtler manifestations of human aggression. There comes a point at which each of us abandons, as illusions, the expectations he pinned to his fellow men when he was young and can appreciate how difficult and painful his life is made by their ill will.

Miles Purinton as Jason, Dogville, Lars von Trier

At the same time it would be unjust to reproach civilization with wanting to exclude contention and competition from human activity. These are certainly indispensable, but opposition is not necessarily enmity: it is merely misused as an occasion for the latter.

Chloë Sevigny as Liz, Dogville, Lars von Trier

‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’: Why would we do it? What good will it do us? But, above all, how shall we achieve it? How can it be possible? My love is something valuable to me which I ought not to throw away without reflection. It imposes duties on me for whose fulfillment I must be ready to make sacrifices. If I love someone, he must deserve it in some way. He deserves it if he is so like me in important ways that I can love myself in him; and he deserves it if he is so much more perfect than myself that I can love my ideal of my own self in him.

Siobhan Fallon Hogan as Martha, Dogville, Lars von Trier

‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’: But if he is a stranger to me and if he cannot attract me by any worth of his own of any significance that he may already have acquired for my emotional life, it will be hard for me to love him. Indeed, I should be wrong to do so, for my love is valued by all my own people as a sign of my preferring them, and it is an injustice to them if I put a stranger on a par with them. But if I am to love him (with this universal love) merely because he, too, is an inhabitant of this earth, like an insect, an earthworm or a grass snake, then I fear that only a small modicum of my love will fall to his share.

Shauna Shim as June, Dogville, Lars von Trier

‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’: Not merely is this stranger in general unworthy of my love, I must honestly confess that he has more claim to my hostility and even my hatred. He seems not to have the least trace of love for me and shows me not the slightest consideration. If it will do him any good he has no hesitation in injuring me, nor does he ask himself whether the amount of advantage he gains bears any proportion to the extent of the harm he does to me. Indeed, he need not even obtain an advantage; if he can satisfy any sort of desire by it, he thinks nothing of jeering at me, insulting me, slandering me and showing his superior power; and the more secure he feels and the more helpless I am, the more certainly I can expect him to behave like this to me.

Lauren Bacall as Ma Ginger, Dogville, Lars von Trier

FILM ACTRESSES & GLOBAL CLASSICS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK OR TAP ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2020 | All rights reserved

Comments

1 thought on “Nicole Kidman Actress 4: Dogville”

What a wonderful, in-depth review. I wholeheartedly agree that Kidman should seek out more challenging roles since she has the ability to fill them so marvelously. I’ll be linking this essay in my blog about impressions from ‘Dogville’.