STRINDBERG – MISS JULIE – A SEQUENCE-BY-SEQUENCE ANALYSIS (1/2) – JESSICA CHASTAIN – SAFFRON BURROWS

MISS JULIE: DRAMA OF THE SEXES – PART 4 – TWO FILM VERSIONS

MIKE FIGGIS & LIV ULLMANN – MISS JULIE – A CRITICAL COMPARISON – 2/3

Richard Jonathan

Richard Jonathan is the author of the literary novel Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms

THIS ESSAY IS SPLIT INTO 3 POSTS. TO READ 1/3, CLICK: CRITICAL COMPARISON 1 OF 3

Saffron Burrows 18 months after Miss Julie | Derrick Santini, 2001

MISS JULIE – A BREAKDOWN OF THE PLAY INTO SIXTEEN SEQUENCES

I aim to conduct this analysis on sound critical principles, and to that end my comparison will proceed sequence by sequence, always starting with Ullmann. Miss Julie being a one-act play with no scene divisions, I will follow Törnqvist and Jacobs’ structural breakdown of the play.1 In the list below, the bits of dialogue or description are meant to serve as identification tags for each sequence, nothing more. For the sake of convenience, each ‘sequence identification tag’ is also placed at the head of each sequence. While both Figgis and Ullmann follow Strindberg’s sequencing, each does make a few minor rearrangements here and there. I remind you, dear reader, that the two touchstones for my analysis, both interpretative and evaluative, are ‘Strindbergian’ and ‘cinematic’, as defined in the preceding post, Miss Julie: Drama of the Sexes – Part 3.

1 – KRISTIN – Prepares abortive potion for Diana the dog.

2 – JEAN & KRISTIN – Miss Julie’s quite crazy again tonight! Absolutely crazy!

3 – JULIE, JEAN & KRISTIN – Would it be wise for your Ladyship to dance twice with the same partner?

4 – KRISTIN – Performs various tasks while Jean and Julie are out dancing.

5 – JEAN & KRISTIN – She really is crazy! | Well, she’s got her monthly now.

6 – JULIE, JEAN & KRISTIN – Charming partner you are, running away from your lady like that!

7 – JULIE & JEAN – Kiss my shoe | I’m on top of a pillar | Something in your eye? | Tall tree, first branch | Playing with fire

8 – JULIE & JEAN – The fuck | Servants revel and go on a rampage

9 – JULIE alone. JULIE & JEAN – Tell me you love me | A whore’s a whore | My mother was a commoner | You hate men

10 – JEAN & KRISTIN – Shame on you! What an evil thing to do! I won’t stay in this house any longer.

11 – JEAN – Tidies the kitchen. Gets his belongings. Packs his suitcase.

12 – JEAN & JULIE – We can’t take the bird. You should have learned to slaughter properly.

13 – JULIE, JEAN & KRISTIN – Help me, Kristin. Save me, save me from this man. Don’t trust this bastard.

14 – JULIE & KRISTIN – What if all three of us were to go abroad together?

15 – JULIE, JEAN & KRISTIN – Oh, if only I had your faith. | God’s grace isn’t given for everyone to receive.

16 – JULIE & JEAN – Take the broom. You’re not one of the first anymore. You belong to the last. The suicide.

1 – Egil Törnqvist & Barry Jacobs, Strindberg’s Miss Julie: A Play and It’s Transpositions (Norwich: Norvick Press, 1988) p. 62. However, where Törnqvist & Jacobs have 18 sequences, I have 16, since, reflecting Figgis and/or Ullmann, I have on two occasions merged a very brief ‘solo’ sequence into the ‘duologue’ or ‘triologue’ one that follows it.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

I. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 1

Kathleen – Preparing abortive potion for Diana the dog

LIV ULLMANN (PROLOGUE + SEQUENCE 1)

Liv Ullmann begins her Miss Julie with a 3m45 prologue of her own devising. In it, we see Julie as a child reading lines that, evidently, refer to herself: ‘She had received a most beautiful doll as a present. Oh, what a glorious doll, so fair and delicate. She did not seem created for the sorrows of this world.’ The ‘fair and delicate doll’ is an all-too-obvious projection of Julie herself: Ullmann, via this wink at Ibsen, is drawing a parallel between Julie and Nora. Later the doll appears high up in a tree: Julie will not be confined to a doll’s house because, like John, she aspires to reach the top of a ‘tall tree in a dark wood’. An earlier scene shows Julie as a child lying face-down across a bed. To the strains of Schubert’s Notturno in E-flat major, she moans ‘Mommy, Mommy’. Like the image, the music evokes tragedy, timelessness, and stasis. Later, in a foreshadowing of adult Julie’s suicide, we see child Julie tossing wildflowers into a stream. From the very get-go, then, Ullmann invites us to see Julie as a victim deserving of pity. I, for one, reject this invitation since, like all spectators who refuse to be led by the nose, I am moved more by a child struggling to hold back her tears than by one who is crying. In ignoring this elementary principle of drama, in giving her opening a wistful, weepy tonality, Ullmann makes her prologue not only anti-dramatic, but also anti-’Strindbergian’ and anti-cinematic.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie

Ullmann’s sequence 1 consists in two shots. In the first, a wide shot, Kathleen, the camera panning with her as she walks at a brisk pace, enters the kitchen from the tunnel and, calling out for the dog, Diana, heads for the stove. In the second, a long shot, Julie climbs from midway to the top of the grand staircase, then turns right: as we saw in the prologue, the baton has been passed from child Julie, who’d walked from the house into the park, to adult Julie, who’d walked from the park into the house. With this splicing of past and present, Ullmann seems to be suggesting that ‘the girl is mother of the woman’.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

A cinematographic tour de force, as dazzling in its music and editing as in its costume and décor, Figgis’ opening sequence immerses us immediately in a sensory experience, its mobile framing and dynamic staging1 a two-minute précis of the entire film. We are in the kitchen as Christine directs the tasks of the servants and their children as their Midsummer Night’s feast is being prepared. To the accompaniment of a string quartet playing a brisk staccato ryhthm,1 we go from the bringing of firewood, through the food preparation, cooking and decoration, to carrying food-laden trays out of the kitchen, and finally to a tired Christine yawning alone: there’s narrative method in the audiovisual madness. Where Ullmann’s overture is undermined by a plodding sentimentality, Figgis’ is swift and exhilarating. Between each shot a credit title, white print on black ground, is interpolated; this, together with the mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame, makes for a much faster pace than the 1 shot every 4.4 seconds indicates. If the confusion is thrilling the ‘content’ is rich, with anecdote and incident—a couple flirting, a woman breast-feeding, Christine leading by his ear a misbehaving boy away—punctuating the feast-preparation. Despite the multiple vectors of movement in the choreography of the abundant cast, never is there a misstep: each cut contributes to the forward momentum, never is the ball dropped. It is as if Mike Figgis, with authority and conviction, has merged the painting of Bruegel with the dance of Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker3, giving us an immersive introduction to Miss Julie’s world.

1 – Benoît Delhomme and Mike Figgis operated, handheld, the two cameras.

2 – Mike Figgis himself composed the score.

3 – I’m thinking of Rain in particular.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy

II. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 2

Jean & Kristin – Miss Julie’s quite crazy again tonight! Absolutely crazy!

LIV ULLMANN

This sequence typifies the style Ullmann will employ throughout the film: a master shot interpolated with medium shots and (medium) close-ups, be they inserts or reaction shots. Well constructed and smooth flowing, it is an academic style easy to take in. Indeed, it is the equivalent of ‘easy listening’ in music: middle-of-the road and mainstream, neither hot nor cold. It politely invites your attention, it does not demand it. Offering no surprises, it is—and promises to remain—predictable. There’s nothing daring or dirty to it, nothing rough or provocative: all is smooth and clean, non-threatening and ‘normal’. It is, in artistic terms, a dead language. So why did its box office fall so far short of its budget?1 After all, recall that there is an inverse relationship between artistic vitality and commercial success.2 The reason, as I see it, is that a portion of the film-viewing public still refuses to perform the auto-lobotomy that would make them zombies like all the rest, furnishing eyeballs to screens and clicks to cash registers in ever-greater numbers. This discerning audience doesn’t like being assimilated to the brain dead. What exactly, in this sequence, insults their intelligence? Little things, like depriving Jean of his aspiration to French sophistication by calling him ‘John’, having him say ‘too cold’ for ‘a little more chambré’, and grossly mispronounce ‘délice’. Bigger things, like the redundant dialogue interpolated by Ullmann that aims to ‘soften’ Strindberg’s hardness and ‘explain’ the obvious. And finally, right across the board, the biggest insult of all: telling rather than showing the spectator what’s going on.

1 – The Numbers.

2 – Especially in cinema, where the brain bypass operation brought about by always-on social media has given such a boost to mindless media consumption.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell

Indeed, this sequence (like the film in its entirety) manifests an inability to create meaning cinematically, to interpret action in filmic terms. Instead, putting pictures to words, it offers an ‘illustration’ of Strindberg’s play: it is not an organic work that ‘stands on its own two feet’. And how could it be otherwise? An aesthetic that prefers safety to risk, familiarity to adventure, and ideology to openness cannot expect any other outcome. As a counter-example, consider Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice (2005). It too is a ‘period film’ and, what’s more, the umpteenth one from Austin’s novel. And yet it has a vigor and freshness, a charm and élan, that derive from the director’s cinematic intelligence. Harnessing Keira Knightley’s charisma to the old work horses of realism and romance, he knew how to create a work that is at once in its time and of ours. Keira Knightley, barefoot on a swing, idling contemplatively: a happenstance put to cinematic use. Art breathes because of such ‘accidents’, and in Liv Ullmann’s Miss Julie, unlike in Joe Wright’s Pride and Prejudice, there are no accidents, only intentions: the film is weaker for it.1

1 – Liv Ullmann did rewrite sections of her script to take advantage of ‘accidents of architecture’ that the location shooting at Castle Coole offered.* The accidents I’m referring to, however, are those that arise after the script is written, in the process of filming, and offer opportunities to do something more interesting than what had been preconceived. I see no evidence in Ullmann’s film of any such accidents.

* See her interview on the DVD of Fräulein Julie (Alamode Film Distribution – Alive, 2015)

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Samantha Morton & Colin Farrell

MIKE FIGGIS

Mike Figgis’ mise-en-scène of this sequence is radically different from Liv Ullmann’s, and, I will argue, far better. To begin, let’s consider Figgis’ aesthetic and attitude to accident:

Film-making has always been expensive. It’s always someone else’s money and therefore there is always a huge pressure to be conventional.1

Usually the best ideas in cinema come out of situations where a tricky problem arises and there isn’t a piece of equipment around to solve it.2

I’ve arrived at a way of making films where I’m very happy to shoot in 16mm. I actually detest 35mm now, I think it’s so clean, antiseptic and boring. Mainstream cinema is shot like a commercial, it’s so pleased with itself to be so well lit and in focus. When you think about painting, the minute painting was liberated by photography, it just went, ‘Great, let’s go and be impressionists, let’s be abstract’. They couldn’t wait to get away from representation, whereas commercial cinema sticks slavishly to it. People say, ‘Why do you want to shoot on 16mm?’ I’d be happy to shoot in High 8 and blow it up! I think the more abstract you can make the image, by whatever means, the more chance you’re going to have of saying something that will hit the subconscious rather than the front of the head. The one thing that keeps me going is the idea that the sound should be fantastic, and that gives you the freedom to be far more adventurous, visually, with what’s happening on the film, and your editing can loosen up.3

1 – Mike Figgis, Foreword to Justin Bowyer, Conversations with Jack Cardiff: Art, Light and Direction in Cinema (UK: Batsford/Pavilion Books, 2014/2003)

2 – Ibid.

3 – Mike Figgis, in Larry Sider et al., editors, Soundscape: The School of Sound Lectures, 1998-2001 (London: Wallflower Press, 2007/2003) pp. 6-7. For the sake of clarity and concision, I have edited and condensed this citation.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

What do these statements tell us about Figgis’ aesthetic and attitude to accident? First, that it is risky to defy convention, but that it is only by defying convention that one can impose an artistic vision. Second, if you do not bend technology and technique to serve your vision, it is you who will become the servant of technology and technique. Third, an artist necessarily aims to ‘hit the subconscious rather than the front of the head’; a filmmaker who is content to ‘hit the front of the head’ foregoes the possibilities of art. On these three points, Figgis clearly falls on the side of defying convention, upholding vision, and ‘hitting the subconscious’.

Figgis used some highly innovative techniques to construct the dense and claustrophobic mise-en-scène. He had a 360-degree one-room stage constructed for the entire film. The action was shot using two hand-held Super 16mm cameras, one in the hands of the cinematographer and one operated by Figgis himself. The action was filmed in sequence, in long, 15-minute takes. A tight space is created around characters, forcing the audience to focus on their expressions, their mannerisms and movements, while the lighting works in expressionistic contrasts of light and shade.1

Figgis, then, knew how to bend technology and technique to serve his artistic vision; he developed a ‘visually adventurous’ cinematographic style complemented by a ‘loosening up of the editing’ and meticulous attention to the soundtrack.

1 – Del Cullen et al., editors, Contemporary British and Irish Film Directors (London: Wallflower Press, 2001) p. 93

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

Now let’s consider Figgis’ mise-en-scène. First, we note that within the 28 shots in the sequence’s 4min20, the ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’ reconfigures the image multiple times. What is remarkable, in this regard, is that although the sequence moves fast, its dynamics, in terms of pacing and intensity, are precisely modulated and widely varied. This is achieved via judicious shot selection, with shot distances ranging from extreme long shot to close-up, camera angles from oblique to full-on, and an alternation of static and moving, contextual and particular, shots. Two additional techniques that make the cinematography so engaging are the device of filming through an internal frame (a lattice partition, for instance), and the use of depth of field to place, for example, Jean in the distant background and Christine in the close foreground. This technique serves more than just the ‘text’: it also serves the subtext. Here, this consists in two lines that will converge into one. The first is Christine’s anger at Jean for arriving late; the second is Jean and Christine’s anticipation of enjoying a Midsummer Night fuck together. This anger and anticipation merge to create an erotic excitement that feeds very effectively into the next sequence where Julie, ‘in heat’, comes to demand some foreplay for herself via a dance with Jean.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

This sequence is emblematic of how the two films differ. Where Ullmann’s is static and flat, all text and no subtext, with words doing most of the dramatic work, Figgis’ is the exact opposite: highly cinematic, fully rounded and rich in subtext. As for his use of words, the sequence bears out what he says here:

You write a script, you put it away, you get it out again. You look at it thinking, ‘Oh, this might be filmed.’ And then you get a pencil and take about 25% of the dialogue out. And you think, ‘I’ve cut it to the bone.’ You start rehearsing, the pencil comes out again, out goes another 25%. You think, ‘I’ve cut it to the bone.’ You get on the set and the actors start speaking the lines and the dynamic is now suddenly very cinematic—’we don’t need those words, just that look.’ And then you think, ‘I’ve done it at last, there’s no more fat on this.’ And then you get in the cutting room and find there’s another 25% that can go.1

Figgis, I conclude, trusts his ability to render drama through means proper to cinema. Ullmann, evidently, does not. One might put her verbal prolixity down to the fact that, having made a career as an actress, words are her stock in trade. But Mike Figgis also came to cinema from acting (theatre). Music, however, both composing and performing, has always been his primary art. Intuitively, I sense that he, intimately aware that ‘all art constantly aspires to the condition of music’,2 adopts musical principles in his filmmaking. Indeed, his mise-en-scène of this sequence can, in fact, be conceived of as a string quartet—which just happens to be the format for the musical score he composed for the film. Figgis’s musical sensibility accounts in large measure, I suggest, for the artistic self-sufficiency of his film.

1 – Mike Figgis, in Larry Sider et al., editors, Soundscape: The School of Sound Lectures, 1998-2001 (London: Wallflower Press, 2007/2003) p. 11. For the sake of clarity and concision, I have edited and condensed this citation.

2 – Walter Pater, ‘The School of Giorgione’, in Studies in the History of the Renaissance (Oxford World’s Classics, 2010) p. 127

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

III. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 3

Julie, Jean & Kristin – Would it be wise for your Ladyship to dance twice with the same partner?

LIV ULLMANN

The blandness of the previous sequence now comes to serve as a foil for this one, with Jessica Chastain bringing an air of mystery, a ‘still waters run deep’ gravitas, to Miss Julie’s entrance. Here Ullmann’s direction is excellent. It’s as if the actress has inspired the director to raise her game. Indeed, the two are in perfect accord, adopting an aesthetic that is the cinematic equivalent of pianist Alex Weissenberg’s observation that ‘the most formidable technical and musical task for a pianist to achieve is not the playing of a bravura piece, but rather to play a slow movement from Beethoven, Mozart or Schubert—to play it well, with perfect nervous and sound control’.1 Artistically, it is indeed the case that succeeding in ‘slow and deep’ is much harder than pulling off ‘fast and shallow’, and it is here that Jessica Chastain proves herself a great actress and Liv Ullmann, in contrast to what she’s shown us earlier, in command of the means to make her points cinematically.

1 – Adapted from Alexis Weissenberg in David Dubal, Reflections from the Keyboard: The World of the Concert Pianist (New York: Summit Books, 1984) 333

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

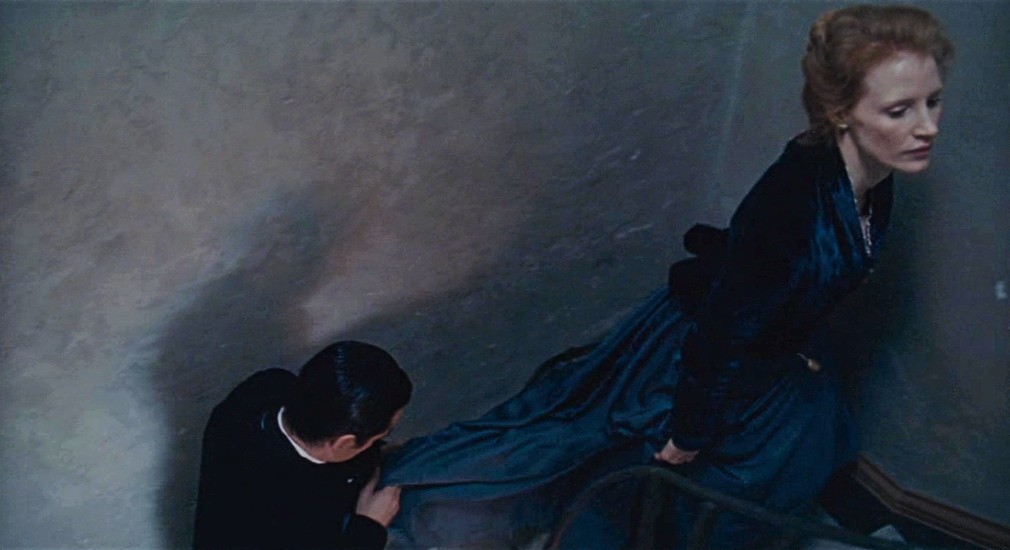

This is particularly evident in the 50-second scene of her own devising that Ullmann added to close the sequence. In it, Julie and John, having stepped out of the kitchen, walk up the stairs to the entrance hall, John following Julie. Midway up the stairs Julie stops. John, after a hesitation pregnant with meaning, picks up the hem of her skirt and holds it as they continue up. The scene is a perfect representation of John’s new-found role of provider of both household and sexual services.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

Julie then walks through the double doors that open out into the entrance hall while John remains standing in the doorway. Having walked down the hallway, Julie walks up the stairs, stops halfway, turns around and looks at John. ‘You’re a man of the future, aren’t you?’, she then asks, daring John to affirm the role of sexual servant she has assigned him. Closing the double doors in her face, as it were, John signals his refusal to service her sexually. In a bold directorial decision, Ullmann then has the camera remain on Julie for a full six seconds as she stands, stranded, on the stairs. This is one of the finest scenes in the film, with Ullmann seizing an opportunity offered by the architecture of Castle Coole to render cinematically the class and sex dynamics that drive Strindberg’s play.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain & Colin Farrell

MIKE FIGGIS

Unlike in Ullmann, where the proscenium stage shadows every shot, here we are more like spectators in a theatre-in-the-round, circulating in an arena: not only are we much closer to the action, we are immersed in it. The effect, reminiscent of 3-D cinema, is enthralling. Now, every viewer of Miss Julie knows that the two key events of the play—the fuck and the suicide—take place off-stage. Every director today must therefore decide, ‘To what extent, if any, should I bring these events back on stage?’. Whatever the answer, the more palpable the actors’ bodies are to the audience throughout the film, the greater the impact on the viewer these two events will have, whether they take place off-stage or on. Aware of this, Mike Figgis, in his mise-en-scène, emphasizes the physicality of the actors. Julie enters running into the kitchen, for example, and slaps Jean in the face (he’d been caressing Christine). Through such staging, Figgis brings forth the metaphysical from the physical, the words from the body. As spectators at this ‘battle of the sexes’, we find ourselves running from one vantage point to another while the film draws from our vicarious physical sensations emotional and intellectual engagement.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Peter Mullan, Saffron Burrows, Maria Doyle Kennedy

Another noteworthy feature of this sequence is the way Julie, in her exchange with Jean, delivers a number of her lines while talking to her bird in its cage, addressing it as ‘sweetheart’. This makes the scene both dramatically richer and more cinematic. Indeed, a principle when dealing with the ineffable, be it in drama, fiction or film, is that ‘detour gives access’. Figgis understands this, and has Julie convey her desire by ‘taking a detour’ via the bird, thus enabling us, the audience, to access it in a way that safeguards its ineffability, that is to say, that does not treat it reductively. It is beautifully done, and Saffron Burrows—unlike Jessica Chastain, an untrained actress—plays it with a candour and freshness that makes it all the more effective.1

1 – Saffron Burrows came to acting from modelling, whereas Jessica Chastain is a graduate of Juilliard.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

IV. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 4

Kristin – Performs various tasks while Jean and Julie are out dancing

LIV ULLMANN

Strindberg had a horror of dogs. In this sequence Kathleen, in the kitchen, picks up the moaning bitch and carries it to her room, telling it along the way that she didn’t put much of the abortive potion in its food. In the room, she winds up a music box and asks the dog if it likes the music. I like to think this is the feminist director thumbing her nose at the misogynist playwright. Dramatically, I find the scene counter-productive, in that its sentimentality enfeebles the film. It is also a lost opportunity: Ullmann, instead of having Kathleen speak to the ‘textuality’ of the scene—the dog is suffering, it needs comforting—could have had her speak to the scene’s ‘sub-textuality’, as she did in sequence 2 where she had Kathleen say, ‘Miss Julie told me she watched them [the dogs fucking] and it made her sick’. This would have reinforced the subtext and highlighted the dramatic line by making the link with Julie and John now gone dancing (as Kathleen supposes). By reverting instead to the sentimentality of her prologue, Ullmann confirms her rejection of Strindberg’s naturalism.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

Shot 1: Christine at the stove. With a certain violence, she lifts the lid off a pot and stirs the pot. Her anger at Julie for taking Jean from her is thus expressed in a physical gesture. Shot 2: The bird in its cage, swiping its beak along its perch: a foreshadowing of the chop-chop. Shot 3: Christine walks over to the cage and, bidding the bird goodnight, throws a sheet over the cage. Shot 4: The dance outside, Jean leading Julie, encircled by cheering revelers. Shot 5: Christine, in a Vermeer-like moment, stands before a mirror in the kitchen, opening her blouse and sponging herself above her breasts. The contrast between the whirling Julie and the still Christine is striking; it reinforces the image of Jean at the apex of a sexual triangle, the two women competing for his favours. Shot 6: Back to the dance, Julie whirling wildly, Jean standing still. Shot 7: A servant cuts in, lifts Julie off her feet and whirls her, leaving her disconcerted. The servant in question is the same man who, later, will utter drunken obscenities as he rampages through the kitchen, clearly hot for Julie who, at that very moment, is getting fucked by Jean. Fade to black.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy

A bold choice, the decision to show the dance was, however, poorly executed. Indeed, not for one second can one believe that Jean’s feeble dancing could ever set Julie aflame. Moreover, Julie’s disconcertion at the end of the scene undermines her insistence on carrying on the revelry later. Given that a good director can accomplish a lot on a shoestring budget and tight schedule but that even a very good director cannot do everything well under such conditions, this scene would better have been left on the cutting room floor.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

V. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 5

Jean & Kristin – She really is crazy! | Well, she’s got her monthly now.

LIV ULLMANN

Exhibiting a static quality typical of the proscenium stage, the long shot that accounts for 65 of this sequence’s 80 seconds nevertheless works because, here, a subtext induces dramatic tension. Indeed, John’s ‘transgression’ with Julie produces an erotic charge that Kathleen’s anger at John for ‘walking off’ with Julie intensifies. Hugging Kathleen playfully from behind, John asks her: ‘Can you imagine what the baron would say if he saw her behavior? Huh? Did you see her?’. To which Kathleen, turning around in his arms to face him, replies (in dialogue added by Ullmann): ‘See her? Is it possible? Are you flattered? Don’t be another dog, will you?’. Upon which he starts barking like a dog while nuzzling her neck. We note the innuendo: John the mongrel dog coupling with the purebred Diana, John the obedient dogsbody. Finally, we register the foreshadowing of ‘Is it possible you fucked her?’ in ‘Is it possible you are flattered?’.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Samantha Morton

We also note a certain smugness in Kathleen, and a body language that accentuates the mother-whore, Kathleen-Julie distinction. Whereas Figgis’ Christine, in her body language, subverts her moral primness, Ullmann’s Kathleen, in her repertoire of attitudes and gestures, confirms it. This exemplifies a major difference between the two films: Figgis gives us a ‘dialectical’ vision of Miss Julie, one in which dissonance and contradiction abound, whereas Ullmann Miss Julie strives towards consonance and accord.1 This is also evident in the soundtrack: where Figgis’ music offers a tonal contrast to the images, Ullmann’s music is in the same tonality as her images. These two examples—how to play Kristin, use of music—typify the contrast between the two directors’ aesthetics.

1 – In the same way that Ullmann adopted Andy Warhol’s dictum, ‘I think everybody should like everybody’ (see Miss Julie Drama of the Sexes Part 3), she also adopts the spirit of that old Coca-Cola commercial, the one whose lyrics go:

I’d like to build the world a home

And furnish it with love

Grow apple trees and honey bees

And snow white turtle doves

(It’s the real thing, Coca Cola)

I’d like to teach the world to sing

In perfect harmony

I’d like to hold it in my arms

And keep it company

(It’s the real thing, Coca Cola)

I’d like to see the world for once

All standing hand in hand

And hear them echo through the hills

For peace through out the land

(It’s the real thing, Coca Cola)

‘I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing (In Perfect Harmony)’ lyrics © Sony/ATV Music Publishing LLC. Songwriters: Roger F. Cook / Roger Greenaway / Roquel Davis / William M Backer.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

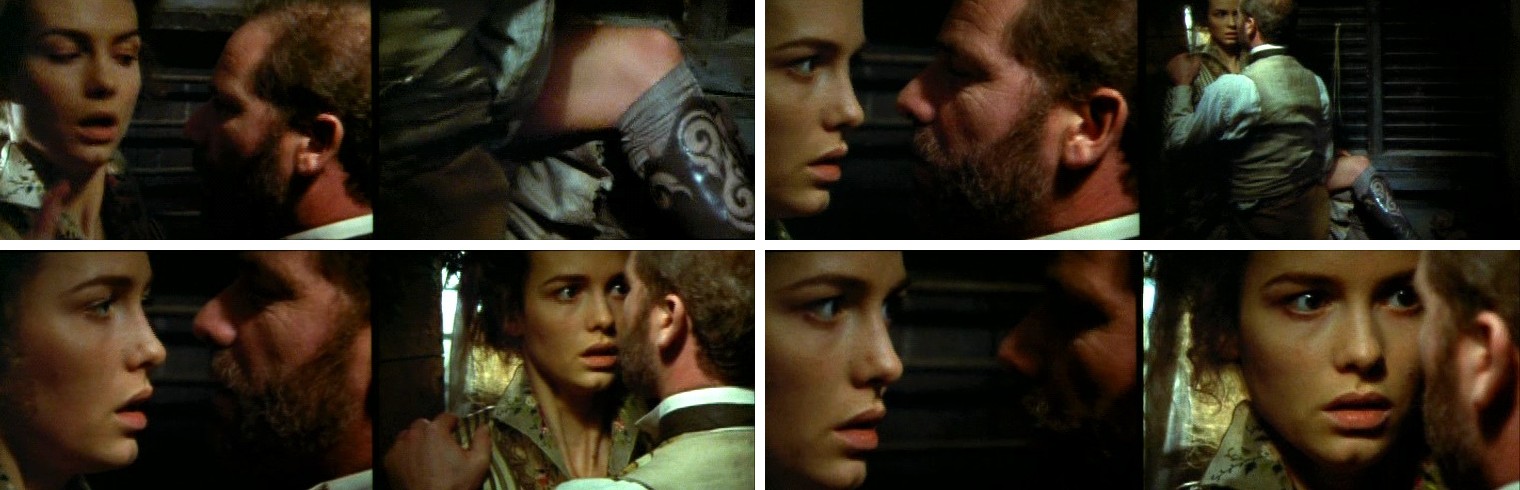

Figgis uses tight close-ups and low-key acting1 to stage this scene as a moment of intimacy between Jean and Christine. As the images in this post and the next one show, his cameras are instrumental in ‘generating’ the drama. His ‘dialectical’ filmmaking is evident here too: while Jean is unbuttoning Christine’s blouse and trying to get at her breasts, they engage in an exchange about what job he could get in their married future. Christine at once accepts Jean’s ardour and cools it (she responds to his caresses as he unbuttons her blouse while diverting the conversation to a banal domestic matter). Jean, for his part, both accommodates her coolness and continues to arouse her (going with the flow of the banal dialogue while ardently pursuing his sexual objective). It is these ‘crosscurrents’ in the Figgis film that make it so engaging. Moreover, this little bit of acting is purely cinematic; it’s a ‘collaboration’, as it were, between the actors and the cameras, and could never be transposed to the stage.2 Once again, we see that the vocabulary and syntax of Figgis’ film is far more cinematic than Ullmann’s.3

1 – This is in marked contrast to Ullmann, where close-ups are few and high-key acting (acting that foregrounds the ‘act of acting’) abounds. This is all the more pronounced in that Ullmann uses the camera strictly as a recording device, rather than, as in Figgis, a device to articulate space or, as in Tarkovsky, an instrument to ‘sculpt in time’.

2 – In contrast, in Ullmann’s film, transposing the acting to the stage would be seamless, for it is already ‘theatrical’.

3 – This suggests that Ullmann, despite her decades of acting—brilliantly!—for the camera, has, behind the camera, fallen back on a style of filmmaking that foregoes risk. Pity, for without risk there can be no creativity, and ultimately, no art.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Maria Doyle Kennedy & Peter Mullan

VI. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 6

Julie, Jean & Kristin – Charming partner you are, running away from your lady like that!

LIV ULLMANN

This sequence suffers from its ‘filmed theatre’ style. It only comes to life when Ullmann ‘dares’ to do a close-up, always on Jessica Chastain,1 but these are only inserts, not integral to the mise-en-scène. As a result, the sequence lacks tension, as is starkly evident in the segment in which John and Julie find themselves alone. It seems as if Ullmann, when there is no dialogue, doesn’t know what to do with the camera.2 Lesson No 1 in filmmaking: The duration of a second is much longer in film than in life. Lesson No 2: If you sacrifice cutting to continuity, you lose ‘cinematicity’. Lesson No 3: A close-up is more engaging than a long shot. Lesson No 4: A hack director can film dialogue scenes adequately; it takes a crack director to make something cinematic out of wordless scenes. Sad to say, Ullmann, here, shows no evidence of having leaned any of these lessons.

1 – Just as well, for Chastain’s acting is rarely less than outstanding.

2 – Having John fail to light the lamp on his first attempt and then express his frustration, for example, or having Julie lick something from her finger after hoisting herself onto the table would not only have enriched the subtext of the scene but also made it more cinematic. How? By dynamically cutting this ‘new’ vocabulary of close-ups into a more interesting syntax than the banal master shot/insert one that Ullmann sticks to most of the time.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

Also noteworthy in this sequence is the prickliness, the high-strung tearfulness, that has crept into Kathleen’s strait-laced starchiness. It’s clear that falling asleep in a chair while John and Julie continue their corrida, as the play has it, is not something she’d be likely to do. Wisely, then, Ullmann has her declare fatigue and go to her room. The way the director has her do it, however—a curious blend of self-righteousness and self-pity1—only reinforces her old-maidish demeanor. This has major consequences, for it makes it impossible for her to pull her weight in the triangle of the love/hate struggle, thus undermining Strindberg’s dramaturgy.

1 – What I’ve called her ‘prickliness’, her ‘high-strung tearfulness’.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Samantha Morton

MIKE FIGGIS

To describe the way Figgis filmed this sequence as ‘bravura’ would be to single it out when in fact the filming of the entire movie is, for the most part, similarly ‘bravura’. And yet it is an inescapable fact that the filming is a tour de force. It is almost as good as the supreme example of ‘filming in the round’, of ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’, namely Andrzej Zulawski’s Possession. It begins with Julie stealthily appearing between the embracing Jean and Christine. On the soundtrack we hear ghostly harmonics played by the string quartet; the effect is otherworldly, eerie. Against this ground Saffron Burrows, in a voice of a viola’s timbre, says matter-of-factly: ‘Jean. He dances like no-one else. Did you know that?’. The delivery is straight, the timbre seductive, and yet the voice is that of one possessed. By what? Desire. Throughout, Burrows acts in close collaboration with the camera; movement, voice, and bodily expression are expertly modulated to convey the precise weight and charge of every word, yet it all comes across as completely natural. Burrows gives the impression she’s walking on water and that we need not be amazed by her magic. Why not? Desire. This is how it moves, like a panther.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan, Maria Doyle Kennedy

The sequence contains several examples of rack focus—moving the focal plane from one object in the frame to another—that express the emotional dynamics at play between the characters. It is cinema, then, that unfolds the drama here, and it is all the more effective because the object of the shifting focus is the face of the actors.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan, Maria Doyle Kennedy

Another fine example of cinematic storytelling is the way Figgis often shows us not the speaker but the listener or observer, as when Julie tells Christine, ‘Yes, but we were officially engaged’, then walks toward Jean. The ‘normal’ thing to do would be to cut to Jean or to follow Julie; instead, Figgis stays on Christine, and has her sneer behind Julie’s back, ‘Nothing came of it, though’.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Maria Doyle Kennedy

As for the incident of Jean changing his jacket, script writer Helen Cooper had placed the Count’s hat and coat on a stand in a corner of the kitchen. So, when Julie orders Jean to get out of his livery and put on the Count’s coat, we have at once an interesting Oedipal dynamic (Jean as a cipher for Julie’s father) and a foreshadowing of Jean’s dream of becoming a Count. We see, once again, that where Ullmann relies on words to tell the story, Figgis, preferring embodiment to abstraction, finds ways to replace words with things. That is cinema, and this sequence is a magnificent example of it.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows, Peter Mullan, Maria Doyle Kennedy

VII. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 7

Julie & Jean – Kiss my shoe | I’m on top of a pillar | Something in your eye? | Tall tree, first branch | Playing with fire

LIV ULLMANN

Throughout this long sequence, Jessica Chastain’s Julie gains in complexity and texture but, paradoxically, loses in dramatic intensity. Indeed, the director having decided that a ‘woman in heat’ is not a worthy feminist motif, has opted instead to turn Julie into a woman in search of her soul. Who am I? What is the meaning of my life? How can I connect with another human being? In Strindberg it is desire1 that drives the drama—the war of the sexes, the class war—and for him Ullmann’s questions are strictly subsidiary. By inverting the priorities of the play, by substituting despair for desire, desperation for determination, Ullmann has made Julie nothing more than a misfit: alienated, disillusioned, lost. From this point on, Miss Julie becomes a movie about two people trying to connect, made by a director who repeatedly cites E.M. Forster—’only connect’—and whose meta-filmic discourse is reducible to ‘I think everybody should like everybody’ (minus, of course, the astringency of Warhol’s irony).

1 – ‘Desire’ is to be understood in the Lacanian sense of unconscious desire. ‘Whenever speech attempts to articulate desire, there is always a leftover, a surplus, which exceeds speech. The realization of desire does not consist in being “fulfilled”, but in the reproduction of desire as such. Desire is not a relation to an object, but a relation to a lack. Desire is essentially desire to be the object of another’s desire. Desire is always the desire for something else, since it is impossible to desire what one already has. Desire is not the private affair it appears to be but is always constituted in a dialectical relationship with the perceived desires of other subjects. Desire is the essence of man and the heart of human existence.’ Compiled from Dylan Evans, An Introductory Dictionary of Lacanian Psychoanalysis (Routledge, 2001/1996) 35-39

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Draining intensity from the drama, Ullmann softens the hard outlines in which Strindberg drew Miss Julie and turns her into a vapid character. Jessica Chastain, flying the flag of sincerity, embodies the director’s vision of the heroine. The epitome of her Pollyanna attitude is to be found in the ‘picnic scene’: Julie grabs a bottle of wine and two glasses and takes John to her favourite spot in the park. ‘Sugar and spice and all things nice’, she listens to him; he takes the hint and piles on the pathos. We have left the realm of Strindbergian truth, derived from an unflinching look at psychological reality, and entered Ullmann’s fantasy world where ‘everybody likes everybody’. Look at the four images below: Chastain, her heart so golden that her skin glows, serves up sincerity on an open-faced sandwich: John the Martyr has only to gobble it up for Ullmann’s loop of goodness to achieve ‘only connect’. Replace the wine with fizzy drink and you’ve got another Coke commercial. A fatal error, for it derails Strindberg’s drama, shunting it onto a dead-end track for dupes.1 Yes, this is a mis-directed movie, made by one who believes a woman’s quest for a fuck is not worthy of her feminism. If only she’d understood that ‘the ego is not master in its own house’,2 she might have seen how richly-textured is that woman’s quest. The irony is that her ‘feminist’ interpretation of Miss Julie, by depriving Julie of agency, is, by virtue of that fact, anti-feminist.

1 – Dupes: those who believe in the possibility of ‘perfect harmony’, as in the Coca-Cola commercial.

2 – Freud, S. (1917) ‘A Difficulty in the Path of Psycho-Analysis’. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud 17:135-144

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

As for John, Ullmann goes out of her way to desexualize him. Repeatedly delivering his lines with all the phoniness of politically correct ‘niceness’ is not the way for a man to get into a woman’s pants. Liv Ullmann wants us to believe John is more interested in Julie’s despair than in her desire, and by imposing such an interpretation on Strindberg’s play she denatures it. ‘No sex please, I’m Norwegian’ doesn’t have quite the right ring to it, does it? Yet that is exactly what Ullmann is saying. A fine example of the ravages ideology wreaks on artistic effort. Unwilling to accept that feminism and fucking can be good bedfellows, Ullmann has John and Julie perform a scene out of some teen romance: John and Julie come down the stairs from the kitchen; John checks that the coast is clear, then takes Julie’s hand and they run, hand-in-hand, along the servants’ alley. Standing face to face, they take shelter under an arch. John kisses Julie. Limp in his arms, she lets herself be kissed. John then runs back to the kitchen, leaving Julie not knowing whether she’s coming or going. Schumann’s ‘Träumerei’, in a version for solo violin, comes on to bathe us in its bittersweetness. Just what is Ullmann up to here? Surely not ‘nice guys kiss before they fuck’ or ‘nice girls play hard to get’? I’ve got it: she is substituting love for sex, the tenderness of a caress for the violence of fucking. Yes, absurd as it may seem, Ullmann, casting a veil over the violence of desire, is raising the possibility of a love story between John and Julie. Very strange. I had thought feminists had had enough of love stories between shining knights and damsels in distress, of sex as kisses in the shadows and vague fumbling in the dark.1

1 – My novel, Mara, Marietta: A Love Story in 77 Bedrooms, proves that an uncompromising treatment of sex in fiction can be at once aesthetically pleasing and true to experience.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Colin Farrell & Jessica Chastain

We also note in this sequence that, where Strindberg has Kristin ‘sleeping like a log’ in her bedroom, Ullmann intercuts her into the scenes with John and Julie. We see Julie, for example, go into Kathleen’s room and offer her a mug of beer. What is Ullmann doing now? By including Kathleen, is she being ‘inclusive’ and ‘intersectional’? Does she want to get a threesome going? Hey, good thing the dog is sick, otherwise who know what ideas Liv might get! Seriously, dear reader, should you need more evidence, this sequence shows that the disavowal of desire is as damaging in art as it is in life.

Julie, Julie, sat on a wall

Julie, Julie, had a great fall

All Liv’s feminism

And all Liv’s correctness

Couldn’t put Julie together again

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain

Liv Ullmann: ‘I found in Miss Julie three people who do not connect. They have every chance, but they don’t listen, they don’t see, and they want to be seen, they want to be listened to.’1 Now let us imagine a conversation between Julie, John and Kathleen where the three really do, as Liv Ullmann understands it, listen to each other. It might go like this:

JULIE: You know, John, I’m really frustrated.

JOHN: I hear you, Miss Julie, but what exactly do you mean?

JULIE: What exactly…? Well, I’m bored with masturbation, fed up with virginity—I really want you to fuck me.

JOHN: I’d love to, Miss Julie. You’re sexy as hell, and I’ve had the hots for you ever since… But why now, why tonight?

JULIE: Because I want to get revenge on my fiancé. The bastard! On my gossiping cousins too—they think I’m at home, all alone, sulking. God what a gas it would be if instead I had you in my bed!

JOHN: (Affecting an oily charm) I understand, Miss Julie, I really do. (With sudden resolution) But you know I’m engaged to Kathleen.

KATHLEEN: (Businesslike) It’s okay with me, John. You and I can fuck anytime. (With Christian charity) Go with Miss Julie tonight.

JULIE: O thank you, Kathleen! I really appreciate it. (Hesitates a moment) But wouldn’t you like to join us?

KATHLEEN: That’s very sweet of you to ask, Miss Julie. But no, I don’t want to tire John out. (Softly, with feminine complicity) I want him all to myself tomorrow.

JOHN: (Taking Julie’s hand and leading her out) I’ll, uh, tomorrow, Kathleen. (A shadow comes over his face; sotto voce) If I can get it up.

JULIE: (Light on her feet, as if already lubricating) Good night, Kathleen. Sleep tight. And don’t let the bugs bite!

KATHLEEN: Good night, Miss Julie. John will fill all your holes, and you’ll be as right as rain in the morning.

John fucked Julie, made love with Kathleen, and all lived happily ever after. And the moral of the story? No amount of ‘listening’ can resolve the ontological conflict induced by sexual difference. A film that pretends otherwise is pulling the wool over the audience’s eyes. Creatures of desire, of longing and lust, audiences are not fooled: Strindberg’s vision, the pulse of their blood tells them, is closer to their own experience than is Ullmann’s view.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Samantha Morton, Colin Farrell, Jessica Chastain

MIKE FIGGIS

In Figgis’ film, Jean and Julie do not engage in discourse as a quest for understanding and respect, aiming at the dissolution of their differences. Instead, as Saffron Burrows embodies Julie’s desire, voice, gesture and attitude concur to make it clear she is in the kitchen to seek a fuck, not a diversion. Jean, as played by Peter Mullan, is at once too worldly-wise to be fooled by a lady in heat and too opportunistic to forego a good thing at hand. Indeed, when nobility rhymes with nubility and peasant with pride, neither aristocrat nor footman will stand on ceremony. And therein lies the genius of this Miss Julie: Mike Figgis is under no illusion that desire can be dissolved in reason and emerge erotic. For him it is the sex war that drives the drama, and ‘feminist’ construals of Julie are a denial of her desire.1 With a dramaturgy based on eroticism and death, he creates a richly cinematic sequence, one in which Julie and Jean take turns plotting the vicissitudes of their desire on the fever chart of their night together.

1 – ‘We are only alive because we desire, yet in our desiring we are obscure to ourselves’. Adapted from Adam Phillips, The Beast in the Nursery (London: Faber & Faber, 1998) p. 107

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

How does Figgis accomplish this? Immersing us in the action: the sequence is shot largely in close-ups—many of them very close-up—enabling the actors to listen in the aura of their intimacy and to speak under their breath. We feel ourselves present beside them—exhilarating. The director, in a stroke of genius, has Burrows express in a hushed voice the violence of Julie’s desire. When Jean brings her the beer she’d asked for, for example, she holds his gaze and says in an undertone, ‘Won’t you join me?’. Dark in timbre, autumnal in color, heavy with the weight of intimation, her voice, like an overripe fig oozing its essence, distils desire. Jean says nothing in response; he simply fetches another bottle and he and Julie fill their glasses. Cinematic: the suppression of the verbal heightens the evocativeness of the visual. ‘Now kiss my shoe’: grapes of desire, heavy on the vine, this line too oozes the ‘fuck me’ that cannot be voiced. Julie, at once confident and vulnerable, is touching because her struggle with herself is no less evident than her combat with Jean.1 Pairing dialogue and action ‘discordantly’: Jean tells Julie about his dream while she, her face inches from his, tries to remove a speck of dirt from his eye. ‘I think you’re all talk. I think you haven’t got it in you’, she says. The kiss that comes to shut her up is filmed in three shots that make clear its mutuality. The body: Jean, kissing a complicit Julie, squeezes her breast: whack! she slaps his cheek. ‘Are you serious or are you joking?’, he asks her. ‘Serious’, she says, upon which he shoves her and she ends up on her ass. The slap in the face, the shove to the ground: the foreplay to the fuck. As freedom embraces destiny and metaphysics the physical, Figgis refuses both the cowardice of caution and the cop-out of coyness: at once anti-moralistic and anti-didactic, his is a cinema for adults.

1- Out of the struggle with others one makes melodrama; out of the struggle with oneself, tragedy.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

Figgis also has Julie and Jean delineate their desire in isolation from each other. Julie confronts herself in a soliloquy, for example, in the scene that follows Jean’s scolding of her for not respecting Christine’s sleep: She rolls with the punches and recovers her cool then lingers at the stained-glass door opening onto the park. The camera follows her in close-up as, fraught with anxiety, she steps outside and stops just before a waterwheel in the background: the wheel of fortune,1 its downward arc ready to wrack Julie in the tragedy to which Strindberg aspired.2 Further on in the scene, we have a close-up of Julie’s wrist as, having risen from the ground onto which Jean had pushed her, she rinses the dirt from her hand. As the water from the tap at the well flows over her flesh (foreshadowing the razor that will slit her wrist), she gazes at her flickering reflection in a muddy pool and says, ‘Everything’s a scum drifting on the water until it sinks’. This soliloquy, like the silent one before, attains a depth of characterization more profound than that in the duo and trio sequences. It also modulates the dramatic pace very effectively, allowing the audience to ‘introject’, as it were, Julie’s introspection.

1 – Foreshadowing both Julie’s ‘I’m on top of a pillar and I can’t get down’ speech and Jean’s ‘I dream that I want to get to the top of that tree’ later in the scene.

2 – Christian Schiaretti: ‘A naturalist tragedy’ as Strindberg subtitled Miss Julie, is an oxymoron. It is an impossibility. Tragedy is a refining of reality, a stripping down to fundamentals. The question of the tragic has to do with an almost metaphysical projection, whereas naturalism is an accumulation of the physical, of verifiable details and everyday banalities. Its aesthetic is opposed to that of the tragic.’ Christian Schiaretti, interview on the DVD of his production of Mademoiselle Julie (Théâtre National Populaire), Collection COPAT/CNC, 2012. Freely translated here by Richard Jonathan.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

We also note in this sequence a remarkable economy of means: one more way Figgis makes his ‘fever chart of desire’ effective. The dialogue has been cut drastically; consequently, because the characters address each other less, they are more present to themselves. This self-presence enriches the film greatly. For instance, on multiple occasions Jean does not answer a question from Julie. The camera stays on Jean in his silence, then cuts to Julie who seems to have understood, or at least accepted, that silence. Denied ‘satisfaction’, desire becomes insistent, propelling the drama forward. For Figgis, less is more (whereas for Ullmann, more is less). Economy of means can also be seen in the ‘mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’. This technique enables the filmmaker to bring out multiple aspects of a scene in a single shot and, what’s more, to achieve dramatic compression and intensity with neither overload nor loss of detail. The challenge, here, consists largely in knowing what to leave out, a story-telling skill that Robert Louis Stevenson, for one, considered paramount. ‘Mobile framing and dynamic staging within the frame’ is, of course, unique to cinema, and it largely explains why Figgis’ film is so cinematic. It is also a technique that, because of its fluidity and ability to reconfigure the frame instantly, is particularly suited to capturing the vicissitudes of desire.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows

VIII. MISS JULIE – SEQUENCE 8

Julie & Jean – The fuck | The servants revel and go on a rampage

LIV ULLMANN

Jean fucks Julie. The intercourse occurs off-stage while the servants revel on-stage. Since Strindberg leaves the sex to our imagination, each spectator’s re-creation of it can be as unrestricted as their phantasy allows. Mike Figgis, as we shall see, shows the intercourse. Liv Ullmann, for her part, simply denies it. Indeed, having already emasculated Jean, she now completes Julie’s desexualization. Instead of a sex scene, on-screen or off, she gives us an asexual one, depicting a man and a woman completely ‘unplugged’ from their sexuality. It could be a scene from a dystopian movie in which the erotic imagination has been disabled, leaving couples to go through the motions of lovemaking without experiencing the emotions. This affront to Strindberg’s drama is the result of Ullmann’s effort to ‘correct’ him. Her misguided feminism denatures sex by denying the play of power and surrender that animates it.1 The Jean she gives us is all sweetness and light—not the stuff that gets a woman wet. It’s quite impossible to imagine him ever having an erection: that blind power beyond the brain’s control is simply too ‘misogynist’ for Ullmann’s ‘feminist’ interpretation of Miss Julie. Yes, dear reader, this is the level at which Ullmann’s philosophy is pitched.2

1 – See Jessica Benjamin’s essay, ‘Sympathy for the Devil’, in MISS JULIE: DRAMA OF THE SEXES, Part 2

1 – See, for example, her Lincoln Center interview

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain & Colin Farrell

As for Julie, her being played by an actress too old for the role1 now proves to be fatal, for her condition of sexual limbo implies a radical lack of curiosity: she is an Eve who has refused the apple, and with it, the core of her humanity. Indeed, she has nothing in common with Strindberg’s Julie, who knew what she wanted was a fuck and the ‘knowledge’ that comes with it. I can’t even imagine Ullmann’s Julie ever using the word ‘fuck’: ‘doing naughty’, or some such childish term, is how she’d describe the vague fondling she performs with Jean. In rewriting Strindberg, Ullmann wanted to ‘femininize’ Julie: she succeeded only in dehumanizing her. Knowing neither what she wants not what she doesn’t want, she is neither here nor there. Whatever tension Ullmann had retained in Strindberg’s drama is now drained. The dramaturgy, as a consequence, has nowhere to go, and this, as we shall see, gives the remainder of the film a false ring. The director’s refusal, in the name of feminism, to give sex its due makes Strindberg’s hot-blooded heroine an anemic creature, both morally—she is incapable of taking responsibility for herself—and physically—she is estranged from her own sexuality and cannot inhabit her body.

1 – Jessica Chastain at 36 was a mature woman, visibly older than Strindberg’s youthful heroine. This changes everything. Why? Because the needle has shifted on the dials of our interpretive grid. For example, in our intuitive understanding of character, we do not view a 36-year old virgin and/or cock teaser in the same way as a 25-year old one. Same goes for the interpretation of other aspects of Julie’s character—her helplessness, her inability to find a way out, her courage, etc.

Liv Ullmann, Miss Julie, Jessica Chastain & Colin Farrell

MIKE FIGGIS

Figgis filmed the sex scene in split screen. I don’t know if he had a loss of nerve, or if time was too tight to do it better, but the filming here is not up to the standard of the rest of the movie. Ideally, he would have had the curtained-off area of the kitchen where the fuck takes place rebuilt as a separate set and, as he did the rest of the film, filmed the fuck ‘in the round’. As it is, the range of angles on the action is too narrow and the views of the two cameras too similar, giving the scene, in contrast to the rest of the film, a very flat appearance. The intercourse itself, from penetration to orgasm, lasts 3m10. Julie and Jean, he leaning into her, stand face-to-face, anxious to escape detection as the revelers roam the kitchen. Two things redeem the poor filming of the fuck: the wit of the kitchen girls’ song and the markers of transgression in the dramaturgy. Here, over the next three text-image rows, are the lyrics to the song:

The Countess of the manor,

So fine and so well bred,

Had balls instead of piss flaps,

The Count found out in bed.

One evening in the east wing,

When they were on the job,

The Count found out the awful truth—

The Countess had a knob!

She whipped him with her chopper,

She whipped him with her dick,

The Count went weak between the knees

‘Cos he’s a useless prick!

A carrot up your shitter,

A carrot up your arse,

If you’re too pissed to get the gist

Just listen to this farce

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

Countess Julie is the daughter,

The kid they did not want,

She is the noble offspring

Of the Countess and the cunt!

Her Ladyship is dainty

[But will she ever get enough?]

Chasing like a bitch in heat

After every bit of rough

She’s horny for the footman

And the blacksmith at the ball,

She’s horny for Christine as well—

Good God! She’ll fuck us all.

A carrot up your shitter,

A carrot up your arse,

If you’re too pissed to get the gist

Just listen to this farce

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

And there is Jean the footman,

Superior and bold,

He licks the arse of the ruling class

With his tongue right up their hole!

He’s surely quite above us,

Refined beyond belief,

But underneath

The slimy git’s a liar and a thief!

So talented and gifted,

He prefers posh wine to beer,

But we all know his secret—

The shirt-lifter is queer!

Oh, a carrot up your shitter,

A carrot up your arse,

If you’re too pissed to get the gist

Just listen to this farce

With great wit and insight, as you can see, the lyrics capture Julie’s family history and the character, as the servant’s perceive it, of Jean and Julie and the Count and his wife.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

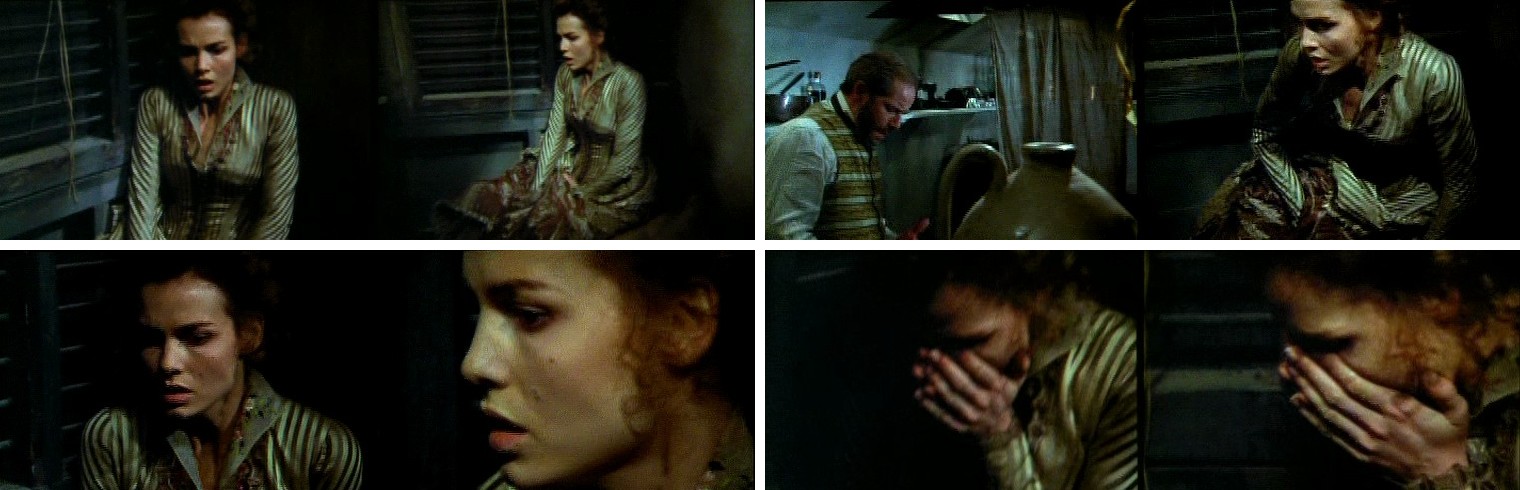

It is at the end of the song that the split screen starts and Jean penetrates Julie. He is standing and she is half-standing, half-sitting (Saffron Burrows being much taller than Peter Mullan).

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The scene is highly erotic, for the markers of transgression are multiple. I’ll mention five:

1. The fuck takes place while the revelers, almost in touching distance to the lovers, are on the rampage in the kitchen.

2. The obscene song is insulting, but arousing to the lovers precisely because it debases them.

3. The lovers are standing, giving the fuck its character of ‘fuck’ in contradistinction to ‘making love’.

4. While Jean is thrusting and Julie adjusting her position (to optimize her pleasure?), Jean is telling her about his project to set up a hotel.

5. Footman fucking Count’s daughter, Count’s daughter being fucked by footman: sex across the class barrier.

Both cameras concentrate on Julie’s face, and Saffron Burrows rises to the challenge of expressing Julie’s anxiety together with her excitement. Even as Julie chases her orgasm there is never the least cliché of sex-scene acting; to the end she walks the tightrope between a dignified awareness of what she’s doing the and the urge to drown herself in loss-of-control.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

At the end, she recognizes what’s happened as a momentous event, and covers her face with her hands. Why? For my part, I opt for ambiguity, the quality most interesting artistically, and most true to life.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

The fact that the fuck is the turning point in the drama, that everything that preceded it was leading up to it, that everything that followed it was derived from it, makes Figgis’ depiction of it, despite its shortcomings, all the more important. The director, in the face of the indolence of both artists and audiences when it comes to imagining sex in cinema, captures more of Miss Julie in the 3m10 of his sex scene than do other productions that, though ‘sexually explicit’, subordinate sex to post-colonial questions, versions of feminism, or political correctness.

Mike Figgis, Miss Julie, Saffron Burrows & Peter Mullan

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RICHARD JONATHAN, MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS – READ THE FIRST CHAPTER

AMAZON & APPLE BOOKS

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | AMAZON PAPERBACK OR KINDLE

RICHARD JONATHAN, ‘MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS’ | APPLE iBOOK

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

RELATED POSTS IN THE MARA MARIETTA CULTURE BLOG

CLICK ON THE IMAGE TO GO TO THE CORRESPONDING PAGE

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2023 | All rights reserved

Comments