LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – IV

STANDING IN THE DOORWAY | FLAMING SEPTEMBER

Bob Dylan | Marianne Faithfull (lyrics) & Angelo Badalamenti (music)

Richard Jonathan

LOVE IN FOURTEEN SONGS – THE FOURTH PAIR

In ‘Standing in the Doorway’ and ‘Flaming September’ the love affair is over, and the ex-lovers adopt different stances to address the fallout.

STANDING IN THE DOORWAY

Bob Dylan | Mark Seliger, 1997

‘Short Letter, Long Farewell’, the title of a 1972 novel by Peter Handke, could well serve as a leitmotif for many a Dylan song. ‘Standing in the Doorway’ is a late instalment in the lover’s long farewell: the song’s tired dignity testifies to the long road travelled. Indeed, its weariness is everywhere. Consider, for example, the self-pity: ‘You left me standing in the doorway, crying’: The lover, giving up the fight, admits defeat; passive, reduced to a spectator, he can only watch as the beloved walks away.

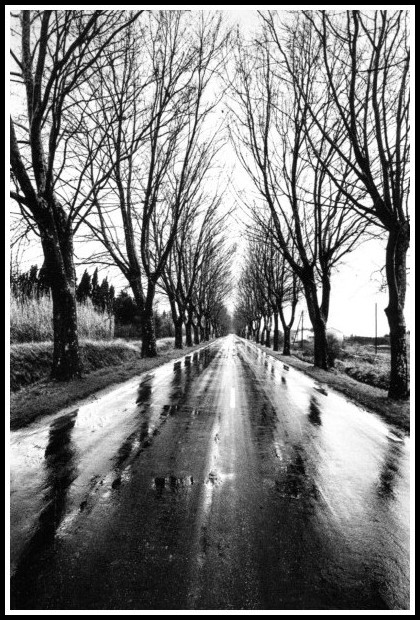

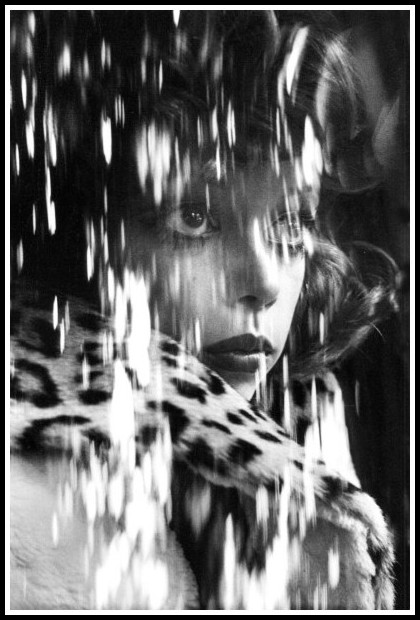

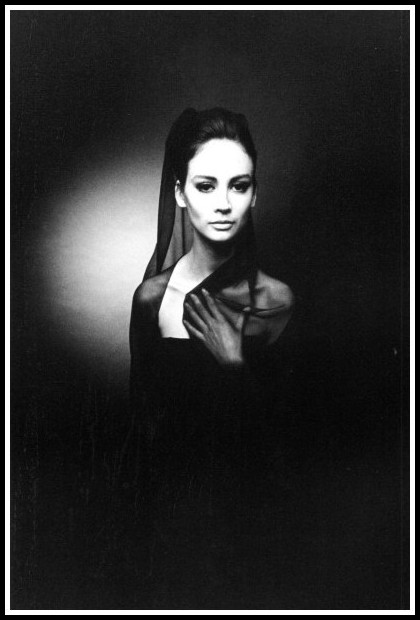

Jeanloup Sieff, Normandie, 1997

The pity slips into pathos: ‘I got no place left to turn’, ‘I got nothing to go back to now’, ‘even if the flesh falls off of my face, I know someone will be there to care’. But the only one who can give him a destination, replace nothing with something, give him the care he cares about, has turned her back on him. His fixation on her, kept alive for so long, has become a weary abdication of responsibility for himself. The lover’s evocation of his state, however, can still be touching. He is out of time: ‘Yesterday everything was going too fast, today it’s moving too slow’. He is out-of-sync with other people: ‘All the laughter is just making me sad’. He is lucid: ‘I know I can’t win, but my heart just won’t give in’.

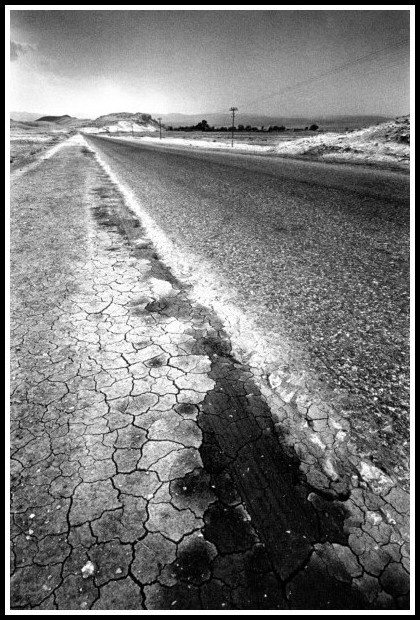

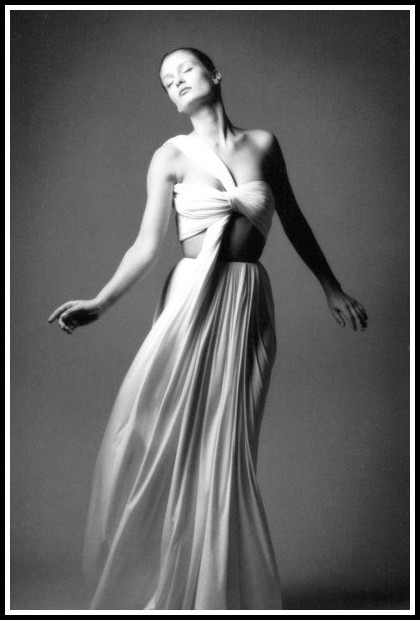

Jeanloup Sieff, Les Baux-de-Provence, 1971

As for his evocation of the relationship itself—the dead horse he’s not quite resigned to stop beating, the tired horse he’s still clinging to on the merry-go-round of his obsession—what he says shows he still has farther to fall. ‘Don’t know if I saw you, if I would kiss you or kill you’ testifies to the hate rejected love can engender, while the devastating line that follows it—‘It probably wouldn’t matter to you anyhow’—makes it clear the beloved has had more than enough of the lover’s beseeching.

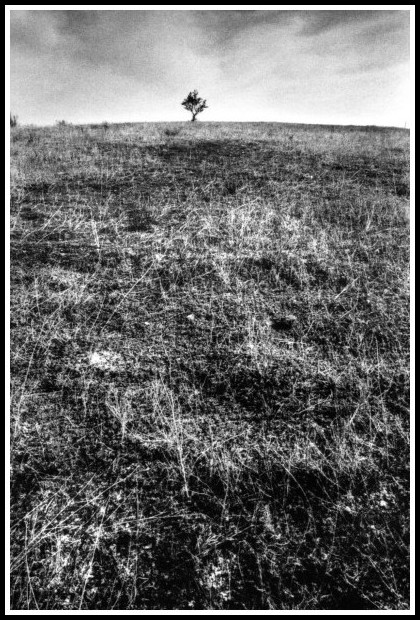

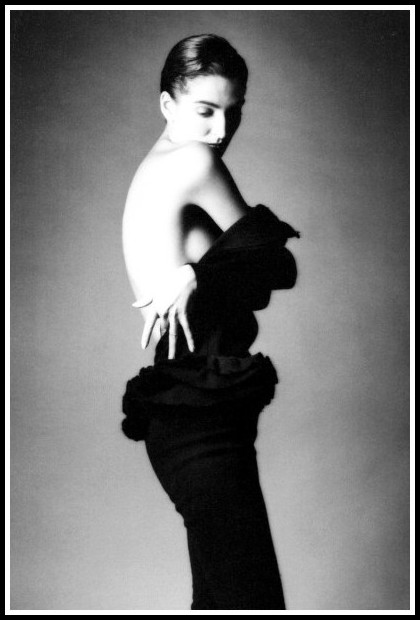

Jeanloup Sieff, Maroc, 1967

‘I would be crazy if I took you back, it would go up against every rule’: a pathetic reversal designed to salvage the man’s pride, for the last thing the woman wants is to be ‘taken back’. ‘I see nothing to be gained by any explanation, there are no words that need to be said’: The communicative impasse, the despair that comes when the coin of language has become a counterfeit currency, here gives way to the fantasy that reciprocal presence may suffice to restore lost communion. But the fantasy is not full-bodied, it’s more a relic of an illusion now given up. Indeed, the lover is aware that he’s ‘standing in the doorway, crying’, and that the beloved is not coming back.

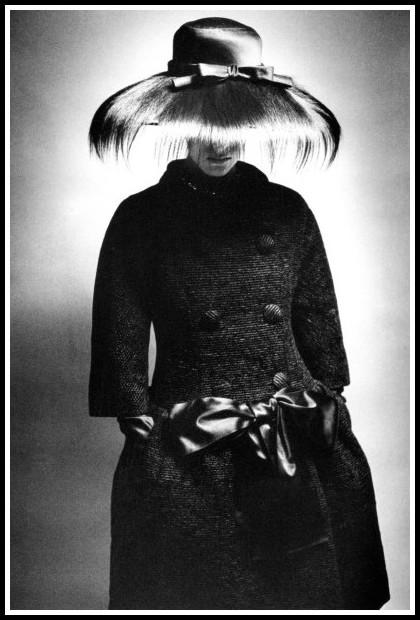

Jeanloup Sieff, Lacoste, 1975

The lover’s inability to accept that the beloved has drawn a line under the relationship, that it’s over and she has moved on, borders on the pathological. If she refuses to slip into the co-dependent slot he has reserved for her, it’s likely because she has learned that ‘love’, in this relationship, rhymes with push and shove. Clearly, the lover is impossibly needy, his demands can never be met, and he is alienated from his own desire. Intuitively, we sense, she understands that he is full of bad faith and will only find grace if she refuses to play his game; her self-respect, then, precludes her from being his partner in dependence. Thus, in rejecting the pathos of his self-pity, she is doing him a service. Indeed, she knows, like Leonard Cohen’s Suzanne, that the way out of the impasse he’s in is through the mirror she, in her silence, is holding out to him.

Jeanloup Sieff, Israel, 1968

STANDING IN THE DOORWAY

Bob Dylan

I’m walking through the summer nights

The jukebox playing low

Yesterday everything was going too fast

Today it’s moving too slow

I got no place left to turn

I got nothing left to burn

Don’t know if I saw you, if I would kiss you or kill you

It probably wouldn’t matter to you anyhow

You left me standing in the doorway crying

I got nothing to go back to now

The light in this place is so bad

Making me sick in the head

All the laughter is just making me sad

The stars have turned cherry red

I’m strumming on my gay guitar

Smoking a cheap cigar

The ghost of our old love has not gone away

Don’t look like it will anytime soon

You left me standing in the doorway crying

Under the midnight moon

Maybe they’ll get me and maybe they won’t

But not tonight and it won’t be here

There are things I could say but I don’t

I know the mercy of God must be near

I’ve been riding the midnight train

Got ice water in my veins

I would be crazy if I took you back

It would go up against every rule

You left me standing in the doorway crying

Suffering like a fool

When the last rays of daylight go down

Buddy, you’ll roll no more

I can hear the church bells ringing in the yard

I wonder who they’re ringing for

I know I can’t win

But my heart just won’t give in

Last night I danced with a stranger

But she just reminded me you were the one

You left me standing in the doorway crying

In the dark land of the sun

I’ll eat when I’m hungry, drink when I’m dry

And live my life on the square

And even if the flesh falls off of my face

I know someone will be there to care

It always means so much

Even the softest touch

I see nothing to be gained by any explanation

There are no words that need to be said

You left me standing in the doorway crying

Blues wrapped around my head

FLAMING SEPTEMBER

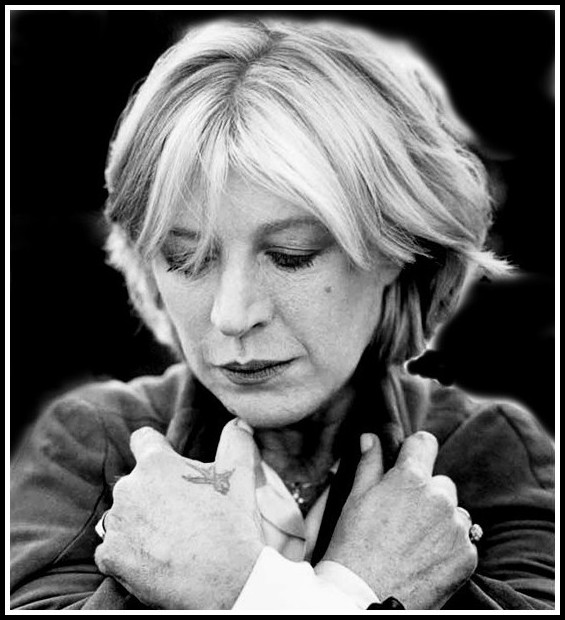

Marianne Faithfull | Jim Rakete, 1999

How does ‘Flaming September’ respond to ‘Standing in the Doorway’? With gravity and grace, with compassion and determination. Here, the woman is fully a subject, not defining herself against the lover who has gone. Her stance is entirely free of the sentimentality, the self-aggrandizement and the self-pity that characterizes ‘Standing in the Doorway’.

Jeanloup Sieff, ‘Mouche’, 1968

Her vision has been purified by the flames she’s been through, and those flames, we sense, date before any particular September. The witches, the weird sisters, are dancing; it goes without saying there’s ‘no happy ending to the game’. Armed with such lucidity, the woman will never be taken for a ride on a dead horse.

Jeanloup Sieff, Robe Madame Grès, 1980

She could show disdain, she could heap contempt, on the man who’s gone; instead, she simply reminds him of ‘all the life she gave to [him]’. Note that she says ‘life’, not ‘love’, for what passes for love (as we saw in the Dylan song) can often be deathly. She already knows the answer to the questions she asks, ‘What can you give me that is true?’, ‘What can you show me that is new?’. The authentic can touch her, she’s open to discovery, but she knows where it’s not coming from: ‘Don’t bother to call me’, ‘Don’t bother to tell me’.

Jeanloup Sieff, Jean-Marc Sinan mode, 1987

And while her ‘youth lies bruised and broken’, she takes responsibility for it: ‘I’ll live on here just the same’. She doesn’t claim to be self-contained, she does say she doesn’t need anyone, but she knows who and what she doesn’t want.

Jeanloup Sieff, Queen (London), 1961

Where ‘Standing in the Doorway’ displays a weariness that, despite the long road travelled, still can’t accept the independence of the other, ‘Flaming September’ shows not a personal but a world-weariness, one that, paradoxically, is free of complacency. Indeed, neither denying vulnerability nor making an exhibition of it, the song is all the more touching for being free of both illusion and self-pity: the dignity and courage evident in it testify to a life lived in self-respect and responsibility.

Jeanloup Sieff, Harper’s Bazaar, 1962

FLAMING SEPTEMBER

Marianne Faithfull – Angelo Badalamenti

The summer dying

September lives in flames

The sisters dancing

No happy ending to the game

Don’t bother to call me

Think I’ll stay here just the same

Flaming September

What can you give me that is true?

Do you remember

Do you remember

Do you remember

All the life I gave to you?

The summer dying

September lives in flames

My youth lies bruised and broken

No happy ending to the game

Don’t bother to tell me

I’ll live on here just the same

Flaming September

What can you show me that is new?

My heart remembers

Do you remember

Do you remember

All the life I gave

To you?

Flaming September

What can you show me that is true?

My heart remembers

Do you remember

Do you remember

All the life I gave

To you?

Flaming September

MARA, MARIETTA: A LOVE STORY IN 77 BEDROOMS

A literary novel by Richard Jonathan

By Richard Jonathan | © Mara Marietta Culture Blog, 2022 | All rights reserved

Comments